Feeding the 8.2 billion people who inhabit the planet depends on healthy soils.

Yet, soil health has been declining over the years, with more than one-third of the world’s agricultural land now described by scientists as “degraded”.

Furthermore, the world’s soils have lost 133bn tonnes of carbon since the advent of agriculture around 12,000 years ago, with crop production and cattle grazing responsible in equal part.

As a result, since the early 1980s, some farmers have been implementing a range of practices aimed at improving soil fertility, soil structure and soil health to address this degradation.

Soil health is increasingly on the international agenda, with commitments made by various countries within the Global Biodiversity Framework, plus a declaration at COP28.

Yet, there is still a lack of knowledge about the state of soils, especially in developing countries.

Below, Carbon Brief explains the state of soil health across the world’s farmlands, the factors that lead to soil degradation and the potential solutions to regenerate agricultural soils.

- What is soil health?

- Why are agricultural soils being degraded?

- Why is soil health important for food security and climate mitigation?

- How can CO2 removal techniques improve soil carbon?

- How can agricultural soil be regenerated?

- What international policies promote soil health?

What is soil health?

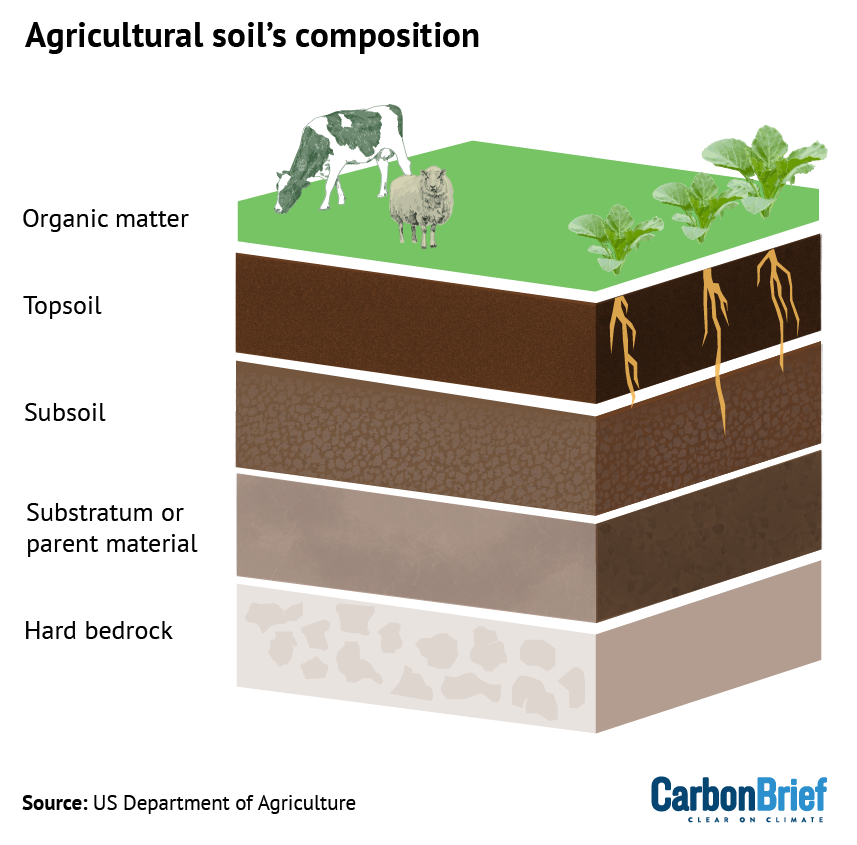

Agricultural soil is composed of four layers, known as soil horizons. These layers contain varying quantities of minerals, organic matter, living organisms, air and water.

The upper layers of soil are rich in organic matter and soil organisms. This is where crops and plants thrive and where their roots can be found.

Below the topsoil is the subsoil, which is more stable and accumulates minerals such as clay due to the action of rain, which washes down these materials from the topsoil to deeper layers of the soil.

The subsoil often contains the roots of larger trees. The deeper layers include the substrate and bedrock, which consist of sediments and rocks and contain no organic matter or biological activity.

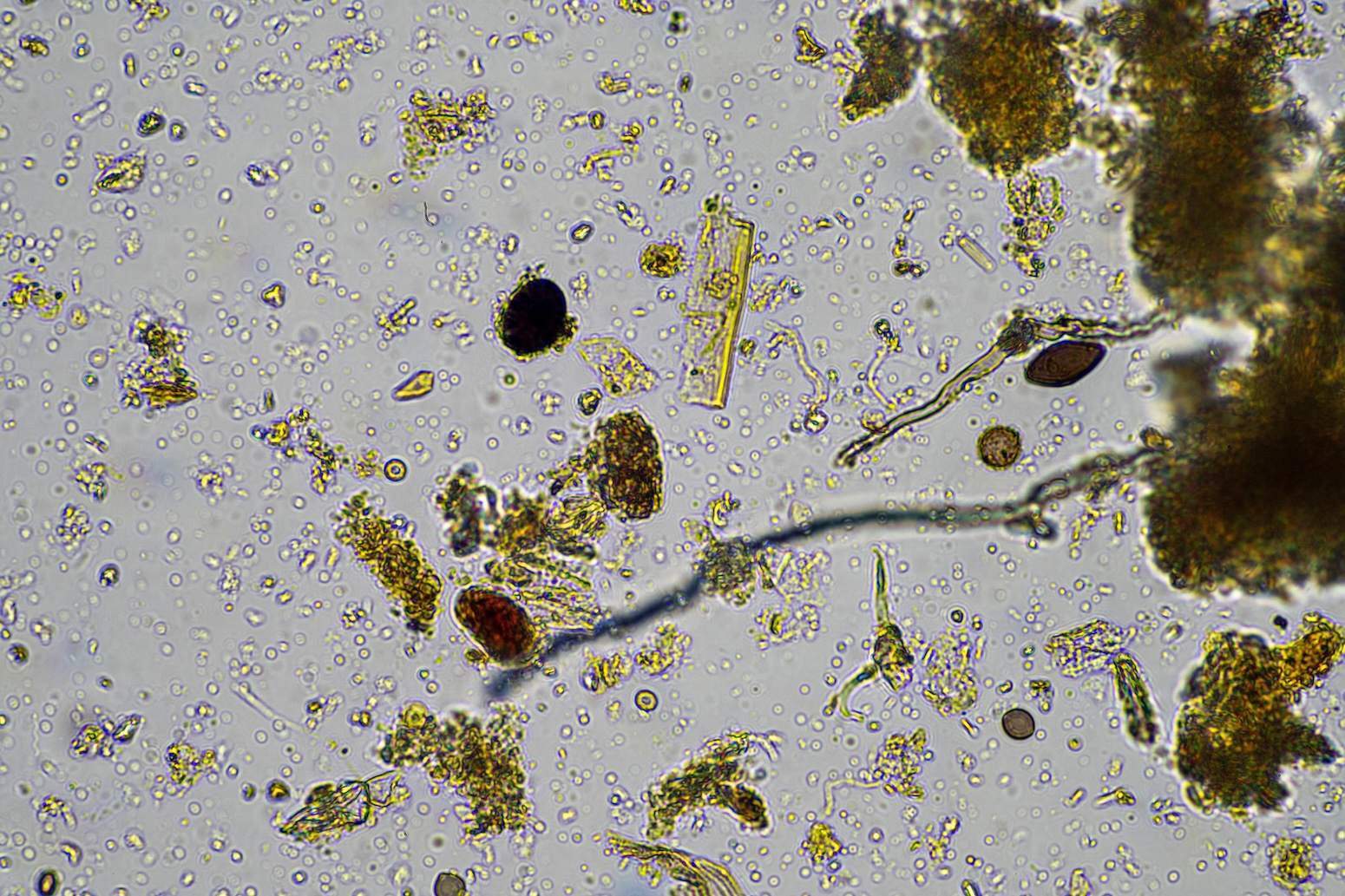

Soil organic matter consists of the remains of plants, animals and microbes. It supports the soil’s ability to capture water and prompts the growth of soil microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, says Dr Helena Cotler Ávalos, an agronomic engineer at the Geospatial Information Science Research Center in Mexico.

Some of these organisms can help roots find nutrients, even over long distances, while others transform nutrients into forms that plants can use. Cotler Ávalos tells Carbon Brief:

“Life in the soil always starts by introducing organic matter.”

Soil is typically classified into three types – clay, silt and sand – based on the size and density of the soil’s constituent parts, as well as the mineral composition of the soil. Porous, loamy soils – a combination of clay, silt and sand – are considered the most fertile type of soil. The mineral composition also influences the properties of the soil, such as colour.

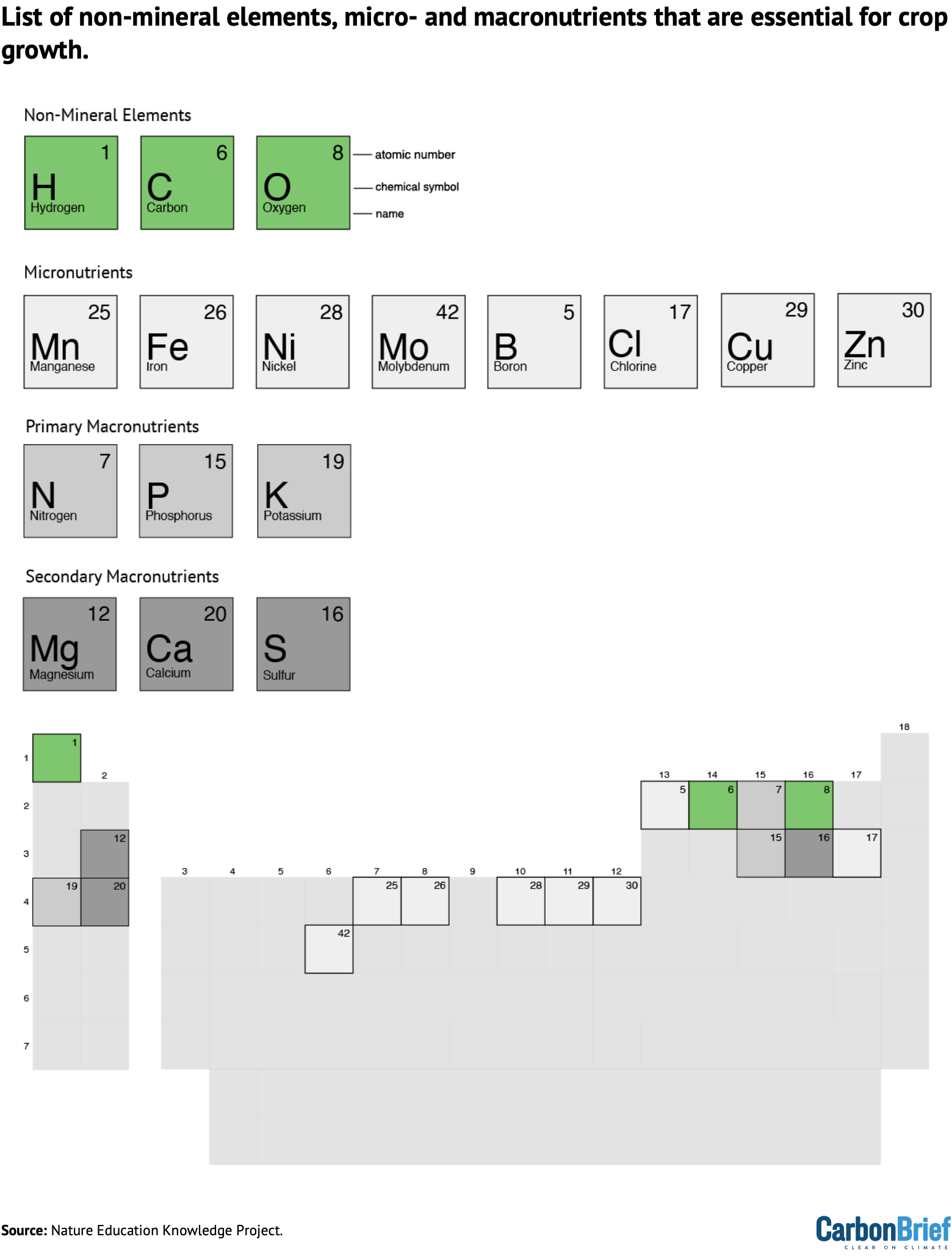

Healthy soils contain three macronutrients – nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium – alongside a range of micronutrients. They also contain phytochemicals, which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and are important for human health.

Below is a graphic showing the elements that constitute healthy soils, including non-mineral elements such as hydrogen, carbon and oxygen (shown in green), according to the Nature Education Knowledge Project.

The concept of “soil health” recognises the role of soil not only in the production of biomass or food, but also in global ecosystems and human health. The Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils – a group of experts that provides scientific and technical advice on soil issues to the Global Soil Partnership at the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) – defines it as the “ability of the soil to sustain the productivity, diversity and environmental services of terrestrial ecosystems”.

Soils can sequester carbon when plants convert CO2 into organic compounds through photosynthesis, or when organic matter, such as dead plants or microorganisms, accumulate in the soil. Soils also provide other ecosystem services, such as improving air and water quality and contributing to biodiversity conservation.

Why are agricultural soils being degraded?

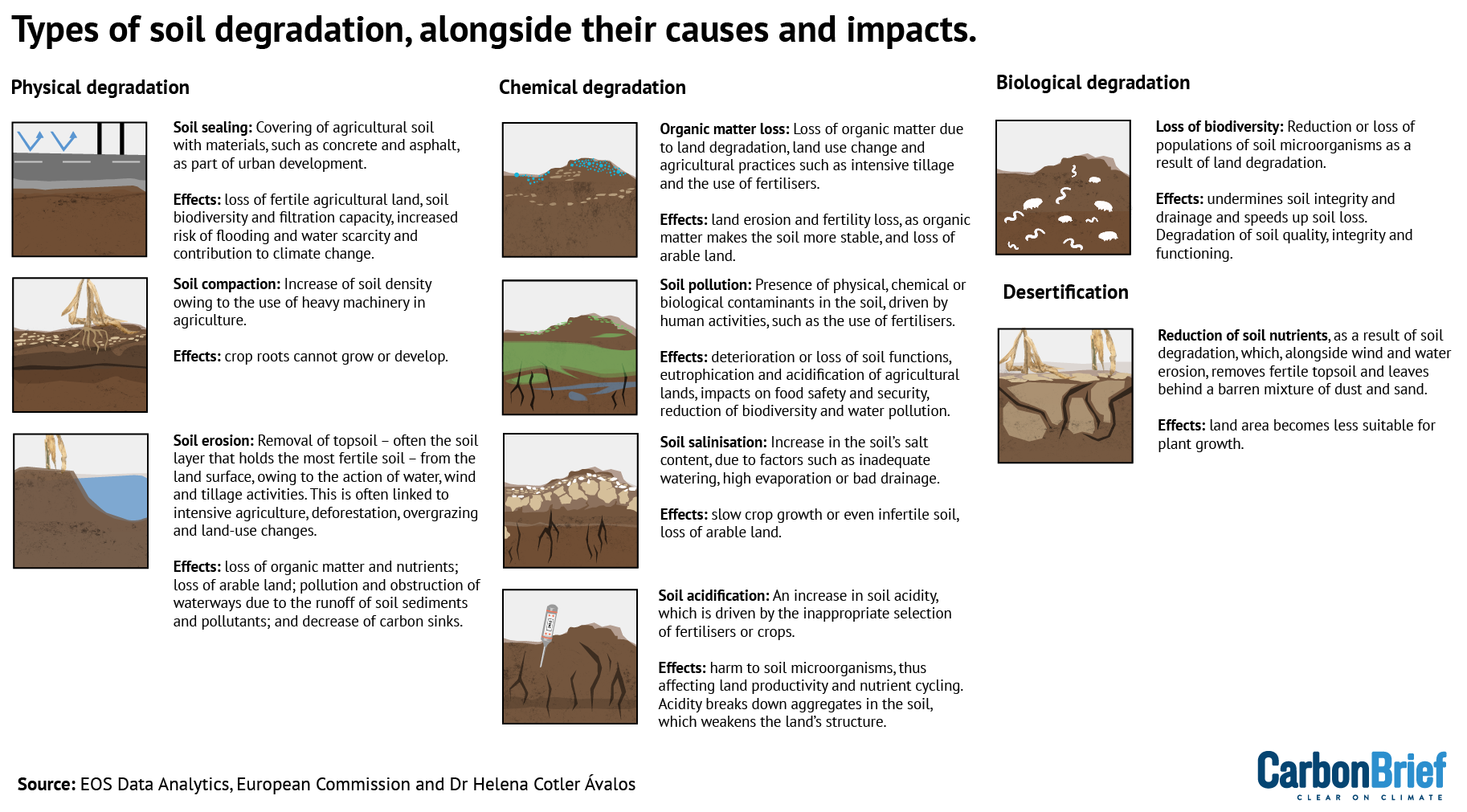

The term “soil degradation” means a decline in soil health, which reduces its ability to provide ecosystem services.

Currently, about 35% of the world’s agricultural land – approximately 1.66bn hectares – is degraded, according to the FAO.

Introduced during the Industrial Revolution, modern-era industrialised agriculture has spread to dominate food production in the US, Europe, China, Russia and beyond.

Modern modes of industrial agriculture employ farming practices that can be harmful to the soil. Examples include monocropping, where a single crop is grown repeatedly, over-tilling, where the soil is ploughed excessively, and the use of heavy machinery, pesticides and synthetic fertilisers.

Agricultural soils are also degraded by overgrazing, deforestation, contamination and erosion.

The diagram below depicts the different types of soil degradation: physical, chemical, biological and desertification.

Types of soil degradation, alongside their causes and impacts. Source: EOS Data Analytics, European Commission and Dr Helena Cotler Ávalos. Credit: Kerry Cleaver for Carbon Brief.

Industrial agriculture is responsible for 22% of global greenhouse gas emissions and also contributes to water pollution and biodiversity loss.

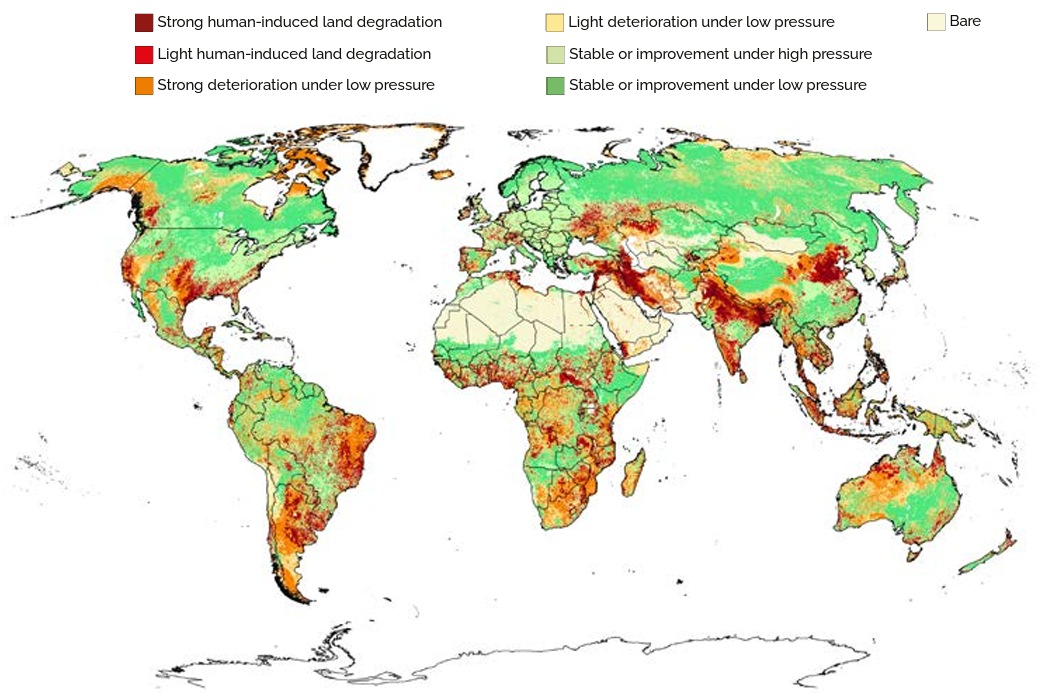

The map below, from the FAO, shows the state of land degradation around the world, from “strong” (dark red) to “stable or improv[ing]” (bright green).

It shows that the most degraded agricultural lands are in the southern US, eastern Brazil and Argentina, the Middle East, northern India and China.

Soil degradation became widespread following the Green Revolution in the 1940s, says Cotler Ávalos. During the Green Revolution, many countries replaced their traditional, diversified farming systems with monocultures. The Green Revolution also promoted the use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides.

These changes led to a “dramatic increase” in yields, but also resulted in disrupting the interactions between microorganisms in the soil.

Cotler Ávalos tells Carbon Brief:

“It is the microorganisms that give life to soils. They require organic matter, which has been replaced by [synthetic] fertilisers.”

Today, there is a widespread lack of data on the condition of soils in developing countries.

For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, there are few studies measuring the rate and extent of soil degradation due to insufficient, reliable data. In Latin America, data on soil carbon dynamics are scarce.

Conversely, the EU released a report in 2024 about the state of its soils, spanning various indicators of degradation, including pollution, compaction and biodiversity change. The report estimates that 61% of agricultural soils in the EU are “degraded”, as measured by changes in organic carbon content, soil biodiversity and erosion levels.

The UK also has its own agricultural land classification maps, which classifies the condition of agricultural soils into categories ranging from “excellent” to “very poor”. This year, a report found that 40% of UK agricultural soils are degraded due to intensive agriculture.

Cotler Ávalos tells Carbon Brief:

“No country in the global south has data on how much of its soil is contaminated by agrochemicals, how much is compacted by the use of intensive machinery, how much has lost fertility due to the failure to incorporate organic matter.

“What is not studied, what is not known, seems to be unimportant. The problem of soil erosion is a social and political problem, not a technical one.”

Improved soil data, indicators and maps can help guide the sustainable management and regeneration of agricultural soils, experts tell Carbon Brief.

Why is soil health important for food security and climate mitigation?

As around 95% of the food the world consumes is produced, directly or indirectly, on soil, its health is crucial to global food security.

Food production needs to satisfy the demand of the global population, which is currently 8.2 billion and is expected to surpass 9 billion by 2037.

A 2023 review study pointed out that the total area of global arable land is estimated at 30m square kilometres, or 24% of the total land surface. Approximately half of that area is currently cultivated.

Studies have estimated that soil degradation has reduced food production by between 13% and 23%.

The 2023 review study also projected that land degradation could cut global food production by 12% in the next 25 years, increasing food prices by 30%.

Another recent study found that, between 2000 and 2016, healthy soils were associated with higher yields of rainfed corn in the US, even under drought conditions.

Research shows that soil health plays an important role in nutrition.

For example, a 2022 study found that a deficiency in plant nutrients in rice paddy soils in India is correlated with malnutrition. The country faces a growing amount of degraded land – currently spanning 29% of the total geographical area – and more than 15% of children are reported to suffer from deficiencies in vitamins A, B12 and D, along with folate and zinc, according to the study.

Soil health is also crucial for mitigating climate change.

Global agricultural lands store around 47bn tonnes of carbon, with trees contributing 75% of this total, according to a 2022 study.

Agricultural soils could sequester up to 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions annually and make a “significant contribution to reaching the Paris Agreement’s emissions reduction objectives”, according to a report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Some farming practices can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve soil carbon sequestration, such as improving cropland and grazing land management, restoring degraded lands and cultivating perennial crops or “cover crops” that help reduce erosion.

However, some scientists have warned that the amount of carbon that can be captured in global soils – and how long that carbon remains locked away – has been overestimated.

For example, an article published in Science in 2023 argued that one of the widely used models for simulating the flow of carbon and nitrogen in soils, known as DayCent, has “plenty of shortcomings”. It says:

“It doesn’t explicitly represent how soils actually work, with billions of microbes feasting on plant carbon and respiring much of it back to the atmosphere – while converting some of it to mineralised forms that can stick around for centuries.

“Instead, the model estimates soil carbon gains and losses based on parameters tuned using published experimental results.”

That, along with uncertainties associated with small-scale estimations, makes the model unable to accurately predict increases or decreases of soil carbon over time and, thus, a positive or negative impact on the climate, the outlet said.

How can CO2 removal techniques improve soil carbon?

Soils can also play a role in mitigating climate change through the use of CO2 removal techniques, such as biochar and enhanced rock weathering.

Biochar is a carbon-rich material derived from the burning of organic matter, such as wood or crop residues, in an oxygen-free environment – a process known as pyrolysis.

Biochar can be added to soils to enhance soil health and agricultural productivity.

Due to its porous nature, biochar holds nutrients in the soil, improving soil fertility, water retention, microbial activity and soil structure.

The long-term application of biochar can bring a range of benefits, such as improving yields, reducing methane emissions and increasing soil organic carbon, according to recent research that analysed 438 studies from global croplands.

However, the study added that many factors – including soil properties, climate and management practices – influence the magnitude of these effects.

Dr Dinesh Panday, a soil scientist at the agricultural research not-for-profit Rodale Institute and an expert in biochar, tells Carbon Brief that biochar typically is applied when soils have low carbon or organic matter content.

He adds that this technique is currently being used mostly in growing high-value crops, such as tomatoes, lettuce and peppers. For staple crops, including rice, wheat and maize, the use of biochar is only at a research stage, he adds.

Enhanced rock weathering is a process where silicate rocks are crushed and added to soils. The rocks then react with CO2 in the atmosphere and produce carbonate minerals, storing carbon from the atmosphere in the soil.

In the US, enhanced weathering could potentially sequester between 0.16-0.30bn tonnes of CO2 per year by 2050, according to a 2025 study.

Panday says that both biochar and enhanced weathering are mostly practised in developed countries at the moment and both have their own benefits and impacts. One of the disadvantages of biochar, he says, is its high cost, as producing it requires dedicated pyrolysis devices and the use of fossil gas. One negative effect of enhanced rock weathering is that it may alter nutrient cycling processes in the soil.

A 2023 comment piece by researchers from the University of Science and Technology of China raised some criticisms of biochar application, including the resulting emissions of methane and nitrous oxide, the enrichment of organic contaminants and heavy metals, and the dispersion of small particulate matter that can be harmful to human health.

Scientists still question how much carbon-removal techniques, such as enhanced rock weathering, can store in agricultural soils and for how long.

How can agricultural soil be regenerated?

Many types of farming practices can help conserve soil health and fertility.

These practices include minimising external inputs, such as fertilisers and pesticides, reducing tillage, rotating crops, using mixed cropping-livestock farming systems, applying manure or compost and planting perennial crops.

Low- or no-till practices involve stopping the large-scale turning over of soils. Instead, farmers using these systems plant seeds through direct drilling techniques, which helps maintain soil biodiversity. A 2021 review study found that in the south-eastern US, reducing tillage enhanced soil health by improving soil organic carbon, nitrogen and inorganic nutrients.

Mixed farming systems, which integrate the cultivation of crops with livestock, have also been found to be beneficial to soil health.

A 2022 study compared a conventional maize-soya bean rotation and a diverse four-year cropping system of maize, soya bean, oat and alfalfa in the mid-western US. It found that, compared to the conventional farm, the diversified system had a 62% increase in soil microbial biomass and a 157% increase in soil carbon.

One of the aims of soil regeneration is to make agricultural soil as much like a natural soil as possible, says Dr Jim Harris, professor of environmental technology at the Cranfield Environment Centre in the UK.

Harris, who is an expert in soil and ecological restoration, says that regenerating soils involves restoring the ecological processes that were once replaced by chemical inputs, while maintaining the soil’s ability to grow crops.

For example, he says, using regenerative agricultural approaches, such as rotational grazing, can help increase soil organic matter and fungi populations.

Which soil regeneration actions will be most successful will depend on the soil type, the natural climatic zone in which a farm is located, the rainfall and temperature regimes and which crops are being cultivated, he adds.

To measure the results of soil regeneration, farmers need to establish a baseline by determining the initial condition of the soil, then assess indicators of soil health. These indicators range from physical indicators, such as root depth, to biological indicators, such as earthworm abundance and microbial biomass.

In Sweden, researchers analysed these indicators in 11 farms that applied regenerative practices either recently or over the past 30 years. They found that the farms with no tillage, integration of livestock and organic matter permanent cover had higher levels of vegetation density and root abundance. Such practices had positive impacts on soil health, according to the researchers.

Switching from conventional to regenerative agriculture may take a farmer five to 10 years, Harris says. This is because finding the variants of a crop that are most resistant to, say, drought and pests could take a “long time”, but, ultimately, farms will have “more stable yields”, he says.

Harris tells Carbon Brief:

“Where governments can really help [is] in providing farmers with funds that allow them to make that transition over a longer period of time.”

Research has found that transitioning towards regenerative agriculture has economic benefits for farmers.

For example, farmers in the northern US who used regenerative agriculture for maize cropping had “29% lower grain production, but 78% higher profits over traditional corn production systems”, according to a 2018 study. (The profit from regenerative farms is due to low seed and fertiliser consumption and higher income generated by grains and other products produced in regenerative corn fields, compared to farms that only grow corn conventionally.)

A 2022 review study found that regenerative farming practices applied in 10 temperate countries over a 15-year period increased soil organic carbon without reducing yields during that time.

Meanwhile, a 2024 study analysing 20 crop systems in North America found that maize and soya bean yields increased as the crop system diversified and rotated. For example, maize income rose by $200 per hectare in sites where rotation included annual crops, such as wheat and barley. Under the same conditions, soya bean income increased by $128 per hectare, the study found.

The study pointed out that crop rotation – one of the characteristics of regenerative agriculture – contributes to higher yields, thanks to the variety of crops with different traits that allow them to cope with different stressors, such as drought or pests.

However, other research has questioned whether regenerative soil practices can have benefits for both climate mitigation and crop production.

A 2025 study modelled greenhouse gas emissions and yields in crops through to the end of the century. It found that grass cover crops with no tillage reduced 32.6bn tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions by 2050, but reduced crop yields by 4.8bn tonnes. The lowest production losses were associated with “modest” mitigation benefits, with just 4.4bn tonnes of CO2e emissions reduced, the study added.

The authors explained that the mitigation potential of cover crops and no tillage was lower than previous studies that overlooked certain factors, such as soil nitrous oxide, future climate change and yields. Moreover, they warned, carbon removal using regenerative farming methods risks the release of emissions back into the atmosphere, if soil management returns to unsustainable practices.

Several of the world’s largest agricultural companies, including General Mills, Cargill, Unilever, Mars and Mondelez, have committed to regenerative agriculture goals. Nestlé, for example, has said that it is implementing regenerative agriculture practices in its supply chain that have had “promising initial results”. It adds that “farmers, in many cases, stand to see an increase in crop yields and profits”. As a result, the firm says it is committed to sourcing 50% of its ingredients from farms implementing regenerative agriculture by 2030.

However, Trellis, a sustainability-focused organisation, cautioned that “these results should be taken somewhat sceptical[ly]”, as there is no set definition on what regenerative agriculture is and measurement of the results is “lacking”.

In some places, the regeneration or recovery of agricultural soils is still practised alongside farmers’ traditional knowledge.

Ricardo Romero is an agronomist and the managing director of the cooperative Las Cañadas – Cloud Forest, lying 1300m above sea level in Mexico’s Veracruz mountains. There, cloud forests sit between tropical rainforest and pine forests, in what Romero considers “a very small ecosystem globally”, optimal for coffee plantations.

His cooperative is located on land previously used for industrial cattle farming. Today, the land is used for agroecological production of coffee, agroforestry and reforestation. The workers in the cooperative are mostly peasants who take on production and use techniques to improve soil fertility that they have learned by doing.

Romero says the soils in his cooperative have improved and crop yields have been maintained thanks to the compost they produce. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We are still in the learning stage. We sort of aspire to achieve what cultures such as the Chinese, Koreans and Japanese did. They returned all their waste to the fields and their agriculture lasted 4,000 years without chemical or organic fertilisers”.

What international policies promote soil health?

Soil health and soil regeneration feature in four of the targets under the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

(There are 169 targets under the SDGs that contain measurable indicators for assessing progress towards each of the 17 goals.)

For example, target 15.3 calls on countries to “restore degraded land and soil” and “strive to achieve a land-degradation neutral world”.

Soil health is increasingly being recognised in international negotiations under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), UN Convention on Biological Diversity (UN CBD) and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), says Katie McCoshan, senior partnerships and international engagement manager for the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU).

Each of these conventions has established its own work groups, declarations and frameworks around soil health in recent years.

Ideally, says McCoshan, action on soils should be integrated across the three different conventions, as well as in conversations around food and nutrition.

However, work across the three conventions remains siloed.

Currently, agriculture is formally addressed under the UNFCCC via the Sharm el-Sheikh joint work on implementation of climate action on agriculture and food security, a four-year work plan agreed at COP27 in 2022. This work group is meant to provide countries with technical support and facilitate collaboration and research.

The COP27 decision that created the Sharm el-Sheikh agriculture programme “recognised that soil and nutrient management practices and the optimal use of nutrients…lie at the core of climate-resilient, sustainable food production systems and can contribute to global food security”.

At COP28 in Dubai, the presidency announced the Emirates Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems and Climate Action. The 160 countries that signed the declaration committed to integrating agriculture and food systems into their nationally determined contributions, national adaptation plans and national biodiversity strategies and action plans (NBSAPs). The declaration also aims to enhance soil health, conserve and restore land.

Harris says the Emirates Declaration is a “great first step”, but adds that it will “take time to develop the precise on-the-ground mechanisms” to implement such policies in all countries, as “they are moving at different speeds”.

Within the UNFCCC process, soil has also featured in non-binding initiatives such as the 4 per 1000, adopted at COP21 in Paris. The initiative aims to increase the amount of carbon sequestered in the top 30-40cm of global agricultural soils by 0.4%, or four parts per thousand, per year.

The UNCCD COP16, which took place in 2024 in Saudi Arabia, delivered a decision to “encourage” countries to avoid, reduce and reverse soil degradation of agricultural lands and improve soil health.

Although COP16 did not deliver a legally binding framework to combat drought, it resulted in the creation of the Riyadh Global Drought Resilience Partnership, a global initiative integrated by countries, international organisations and other countries to allocate $12bn towards initiatives to restore degraded land and enhance resilience against drought.

The COP also resulted in the Riyadh Action Agenda, which aspires to conserve and restore 1.5bn hectares of degraded land globally by 2030.

Although soil health appears under both conventions, it is not included as formally in the UNFCCC as in the UNCCD – as in the latter there is a direct mandate for countries to address soil health and land restoration, McCoshan tells Carbon Brief.

Under the UNCCD, countries have to establish land degradation neutrality (LDN) targets by 2030. To date, more than 100 countries have set these targets.

Under the biodiversity convention, COP15 held in Montreal in 2022 delivered the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), a set of goals and targets aiming to “halt and reverse” biodiversity loss by 2030. Under the framework, targets 10 and 11 reference sustainable management of agriculture through agroecological practices, and the conservation and restoration of soil health, respectively.

A recent study suggests that restoring 50% of global degraded croplands could avoid the emission of more than 20bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent by 2050, which would be comparable to five times the annual emissions from the land-use sector. It would also bring biodiversity benefits and contribute to target 10 of the GBF and to UNCCD COP16 recommendations, the study added.

McCoshan tells Carbon Brief:

“[All] the pledges are important and they hold countries accountable, but that alone isn’t what we need. We’ve got to get the financing right and co-create solutions with farmers, Indigenous people, youth, businesses and civil society as well.”

The post Q&A: The role of soil health in food security and tackling climate change appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: The role of soil health in food security and tackling climate change

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: UK renewables enjoy record year in 2025 – but gas power still rises

The UK’s fleet of wind, solar and biomass power plants all set new records in 2025, Carbon Brief analysis shows, but electricity generation from gas still went up.

The rise in gas power was due to the end of UK coal generation in late 2024 and nuclear power hitting its lowest level in half a century, while electricity exports grew and imports fell.

In addition, there was a 1% rise in UK electricity demand – after years of decline – as electric vehicles (EVs), heat pumps and data centres connected to the grid in larger numbers.

Other key insights from the data include:

- Electricity demand grew for the second year in a row to 322 terawatt hours (TWh), rising by 4TWh (1%) and hinting at a shift towards steady increases, as the UK electrifies.

- Renewables supplied more of the UK’s electricity than any other source, making up 47% of the total, followed by gas (28%), nuclear (11%) and net imports (10%).

- The UK set new records for electricity generation from wind (87TWh, +5%), solar (19TWh, +31%) and biomass (41TWh, +2%), as well as for renewables overall (152TWh, +6%).

- The UK had its first full year without any coal power, compared with 2TWh of generation in 2024, ahead of the closure of the nation’s last coal plant in September of that year.

- Nuclear power was at its lowest level in half a century, generating just 36TWh (-12%), as most of the remaining fleet paused for refuelling or outages.

Overall, UK electricity became slightly more polluting in 2025, with each kilowatt hour linked to 126g of carbon dioxide (gCO2/kWh), up 2% from the record low of 124gCO2/kWh, set last year.

The National Energy System Operator (NESO) set a new record for the use of low-carbon sources – known as “zero-carbon operation” – reaching 97.7% for half an hour on 1 April 2025.

However, NESO missed its target of running the electricity network for at least 30 minutes in 2025 without any fossil fuels.

The UK inched towards separate targets set by the government, for 95% of electricity generation to come from low-carbon sources by 2030 and for this to cover 100% of domestic demand.

However, much more rapid progress will be needed to meet these goals.

Carbon Brief has published an annual analysis of the UK’s electricity generation in 2024, 2023, 2021, 2019, 2018, 2017 and 2016.

Record renewables

The UK’s fleet of renewable power plants enjoyed a record year in 2025, with their combined electricity generation reaching 152TWh, a 6% rise from a year earlier.

Renewables made up 47% of UK electricity supplies, another record high. The rise of renewables is shown in the figure below, which also highlights the end of UK coal power.

While the chart makes clear that gas-fired electricity generation has also declined over the past 15 years, there was a small rise in 2025, with output from the fuel reaching 91TWh. This was an increase of 5TWh (5%) and means gas made up 28% of electricity supplies overall.

The rise in gas-fired generation was the result of rising demand and another fall in nuclear power output, which reached the lowest level in half a century, while net imports and coal also declined.

The year began with the UK’s sunniest spring and by mid-December had already become the sunniest year on record. This contributed to a 5TWh (31%) surge in electricity generation from solar power, helped by a jump of roughly one-fifth in installed generating capacity.

The new record for solar power generation of 19TWh in 2025 comes after years of stagnation, with electricity output from the technology having climbed just 15% in five years.

The UK’s solar capacity reached 21GW in the third quarter of 2025. This is a substantial increase of 3 gigawatts (GW) or 18% year-on-year.

These are the latest figures available from the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ). The DESNZ timeseries has been revised to reflect previously missing data.

UK wind power also set a new record in 2025, reaching 87TWh, up 4TWh (5%). Wind conditions in 2025 were broadly similar to those in 2024, with the uptick in generation due to additional capacity.

The UK’s wind capacity reached 33GW in the third quarter of 2025, up 1GW (4%) from a year earlier. The 1.2GW Dogger Bank A in the North Sea has been ramping up since autumn 2025 and will be joined by the 1.2GW Dogger Bank B in 2026, as well as the 1.4GW Sofia project.

These sites were all awarded contracts during the government’s third “contracts for difference” (CfD) auction round and will be paid around £53 per megawatt hour (MWh) for the electricity they generate. This is well below current market prices, which currently sit at around £80/MWh.

Results from the seventh auction round, which is currently underway, will be announced in January and February 2026. Prices are expected to be significantly higher than in the third round, as a result of cost inflation.

Nevertheless, new offshore wind capacity is expected to be deliverable at “no additional cost to the billpayer”, according to consultancy Aurora Energy Research.

The UK’s biomass energy sites also had a record year in 2025, with output nudging up by 1TWh (2%) to 41TWh. Approximately two-thirds (roughly 27TWh) of this total is from wood-fired power plants, most notably the Drax former coal plant in Yorkshire, which generated 15TWh in 2024.

The government recently awarded new contracts to Drax that will apply from 2027 onwards and will see the amount of electricity it generates each year roughly halve, to around 6TWh. The government is also consulting on how to tighten sustainability rules for biomass sourcing.

Rising demand

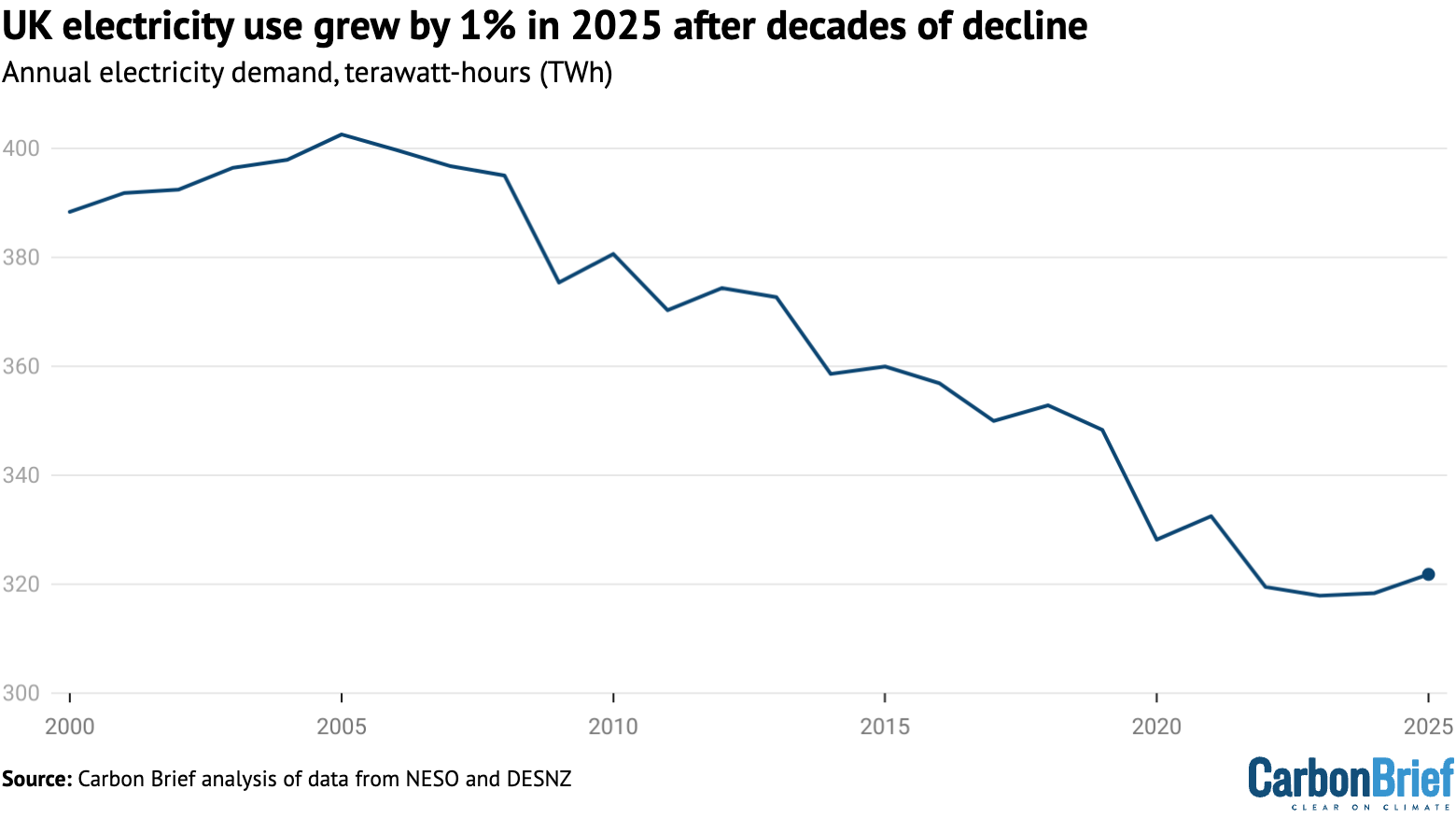

The UK’s electricity demand has been falling for decades due to a combination of more efficient appliances and lightbulbs, as well as ongoing structural shifts in the economy.

Experts have been saying for years that at some point this trend would be reversed, as the UK shifts to electrified heat and transport supplies using EVs and heat pumps.

Indeed, the Climate Change Committee (CCC) has said that demand would more than double by 2050, with electrification forming a key plank of the UK’s efforts to reach net-zero.

Yet there has been little sign of this effect to date, with electricity demand continuing to fall outside single-year rebounds after economic shocks, such as the 2020 Covid lockdowns.

The data for 2025 shows hints that this turning point for electricity demand may finally be taking place. UK demand increased by 4TWh (1%) to 322TWh in 2025, after a 1TWh rise in 2024.

After declining for more than two decades since a peak in 2005, this is the first time in 20 years that UK demand has gone up for two years in a row, as shown in the figure below.

While detailed data on underlying electricity demand is not available, it is clear that the shift to EVs and heat pumps is playing an important role in the recent uptick.

There are now around 1.8m EVs on the UK’s roads and another 1m plug-in hybrids. Of this total, some 0.6m new EVs and plug-in hybrids were bought in 2025 alone. In addition, around 100,000 heat pumps are being installed each year. Sales of both technologies are rising fast.

Estimates from the NESO “future energy scenarios” point to an additional 2.0TWh of demand from new EVs in 2025, compared with 2024. They also suggest that newly installed heat pumps added around 0.2TWh of additional demand, while data centres added 0.4TWh.

By 2030, NESO’s scenarios suggest that electricity use for these three sources alone will rise by around 30TWh, equivalent to around 10% of total demand in 2025.

EVs would have the biggest impact, adding 17TWh to demand by 2030, NESO says, with heat pumps adding another 3TWh. Data-centre growth is highly uncertain, but could add 12TWh.

Gas growth

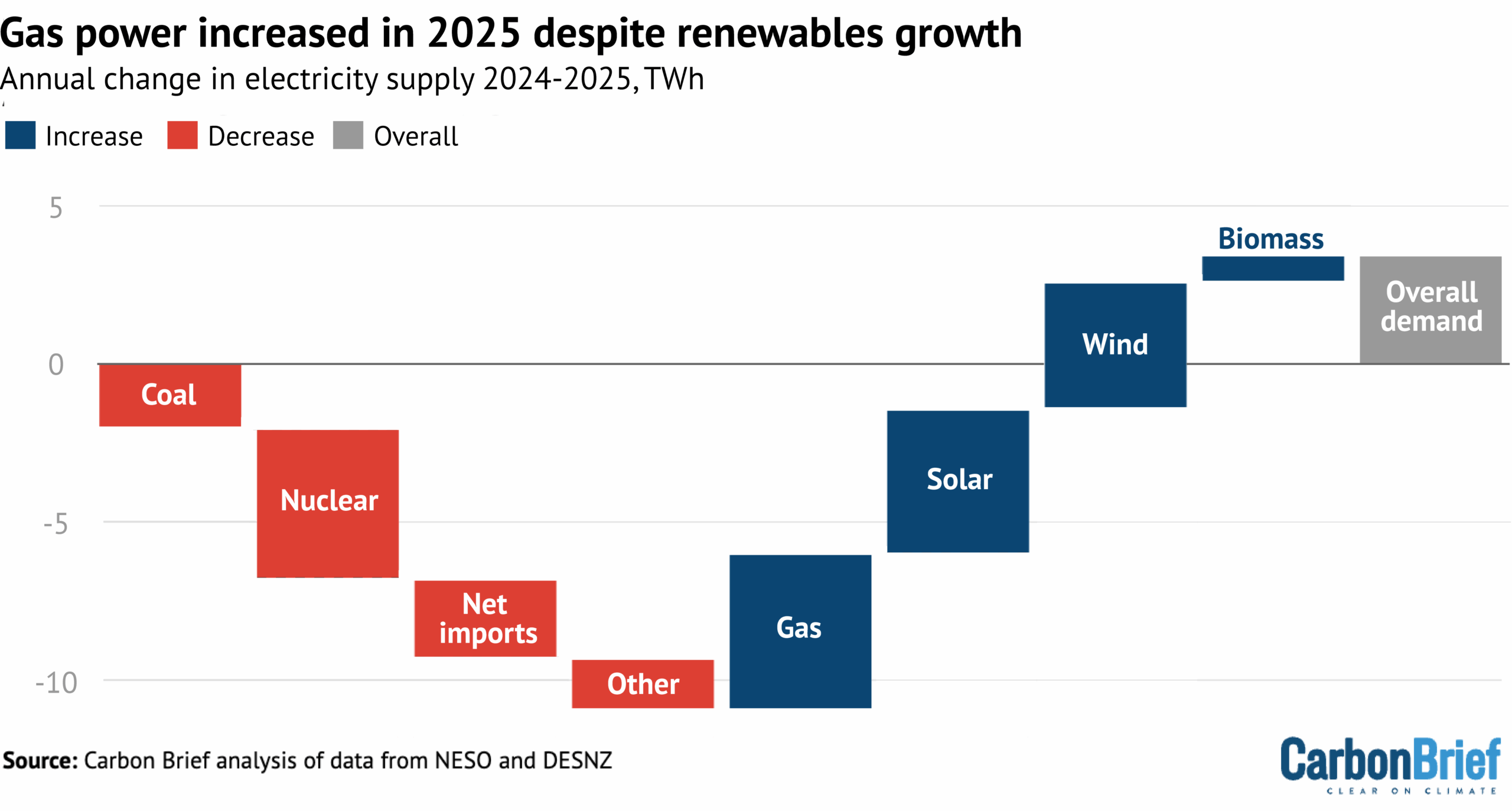

At the same time as UK electricity demand was growing by 4TWh in 2025, the country also lost a total of 10TWh of supply as a result of a series of small changes.

First, 2025 was the UK’s first full year without coal power since 1881, resulting in the loss of 2TWh of generation. Second, the UK’s nuclear fleet saw output falling to the lowest level in half a century, after a series of refuelling breaks and outages, which cut generation by 5TWh.

Third, after a big jump in imports in 2024, the UK saw a small decline in 2025, as well as a more notable increase in the amount of electricity exported to other countries. This pushed the country’s net imports down by 1TWh (4%).

The scale of cross-border trade in electricity is expected to increase as the UK has significantly expanded the number of interconnections with other markets.

However, the government’s clean-power targets for 2030 imply that the UK would become a net exporter, sending more electricity overseas than it receives from other countries. At present, it remains a significant net importer, with these contributions accounting for 109% of supplies.

Finally, other sources of generation – including oil – also declined in 2025, reducing UK supplies by another 2TWh, as shown in the figure below.

These losses in UK electricity supply were met by the already-mentioned increases in generation from gas, solar, wind and biomass, as shown in the figure above.

The government’s targets for decarbonising the UK’s electricity supplies will face similar challenges in the years to come as electrification – and, potentially, data centres – continue to push up demand.

All but one of the UK’s existing nuclear power plants are set to retire by 2030, meaning the loss of another 27TWh of nuclear generation.

This will be replaced by new nuclear capacity, but only slowly. The 3.2GW Hinkley Point C plant in Somerset is set to start operating in 2030 at the earliest and its sister plant, Sizewell C in Suffolk, not until at least another five years later.

Despite backing from ministers for small modular reactors, the timeline for any buildout is uncertain, with the latest government release referring to the “mid-2030s”.

Meanwhile, biomass generation is likely to decline as the output of Drax is scaled back from 2027.

Stalling progress

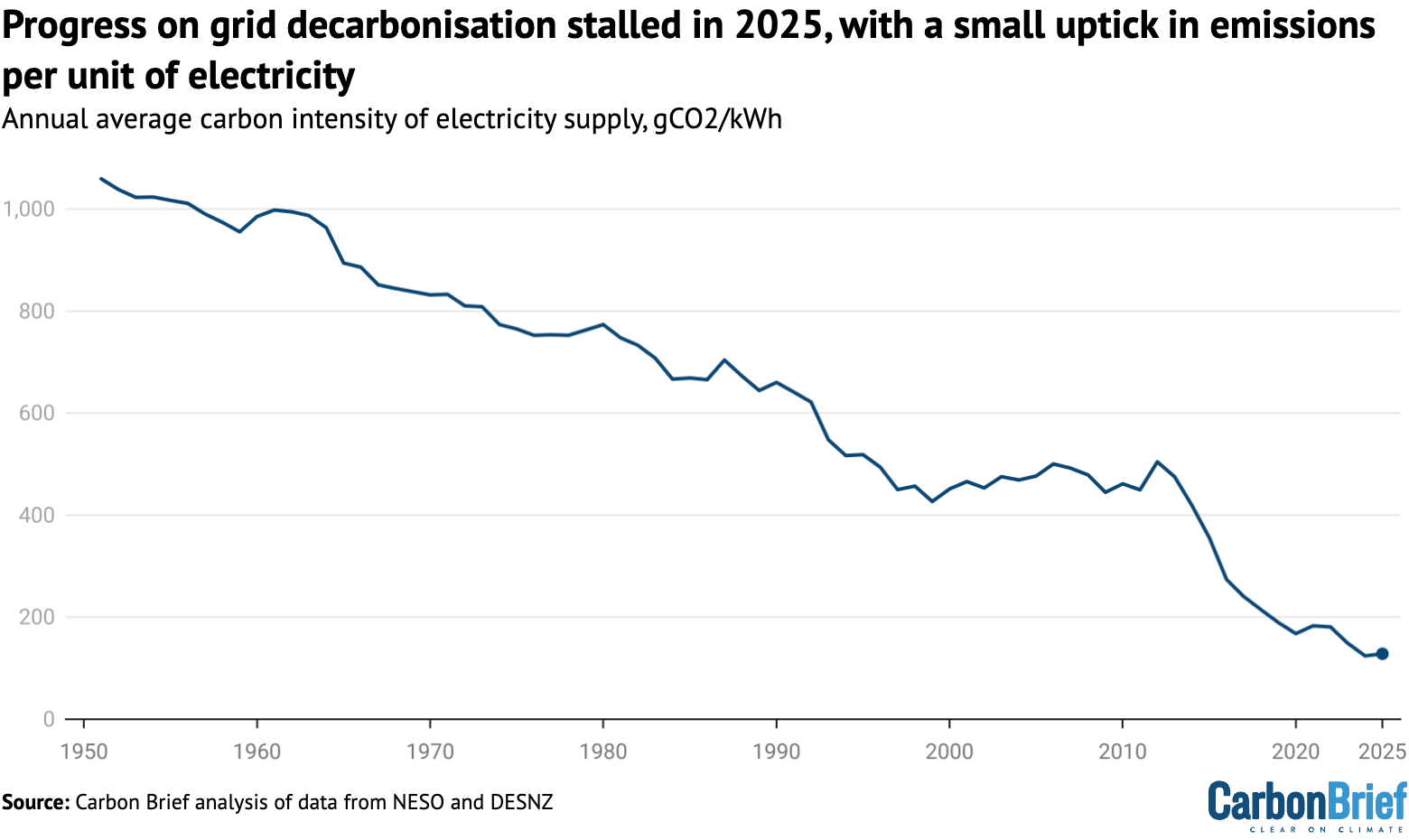

Taken together, the various changes in the UK’s electricity supplies in 2025 mean that efforts to decarbonise the grid stalled, with a small increase in emissions per unit of generation.

The 2% increase in carbon intensity to 126gCO2/kWh is illustrated in the figure below and comes after electricity was the “cleanest ever” in 2024, at 124gCO2/kWh.

The stalling progress on cleaning up the UK’s grid reflects the balance of record renewables, rising demand and rising gas generation, along with poor output from nuclear power.

Nevertheless, a series of other new records were set during 2025.

NESO ran the transmission grid on the island of Great Britain (GB; namely, England, Wales and Scotland) with a record 97.7% “zero-carbon operation” (ZCO) on 1 April 2025.

Note that this measure excludes gas plants that also generate heat – known as combined heat and power, or CHP – as well as waste incinerators and all other generators that do not connect to the transmission network, which means that it does not include most solar or onshore wind.

NESO was unable to meet its target – first set in 2019 – for 100% ZCO during 2025, meaning it did not succeed in running the transmission grid without any fossil fuels for half an hour.

Other records set in 2025 include:

- GB ran on 100% clean power, after accounting for exports, for a record 87 hours in 2025, up from 64.5 hours in 2024.

- Total GB renewable generation from wind, solar, biomass and hydro reached a record 31.3GW from 13:30-14:00 on 4 July 2025, meeting 84% of demand.

- GB wind generation reached a record 23.8GW for half an hour on 5 December 2025, when it met 52% of GB demand.

- GB solar reached a record 14.0GW at 13:00 on 8 July 2025, when it met 40% of demand.

The government has separate targets for at least 95% of electricity generation and 100% of demand on the island of Great Britain to come from low-carbon sources by 2030.

These goals, similar to the NESO target, exclude Northern Ireland, CHP and waste incinerators. However, they include distributed renewables, such as solar and onshore wind.

These definitions mean it is hard to measure progress independently. The most recent government figures show that 74% of qualifying generation in GB was from low-carbon sources in 2024.

Carbon Brief’s figures for the whole UK show that low-carbon sources made up a record 58% of electricity supplies overall in 2025, up marginally from a year earlier.

Similarly, low-carbon sources made up 65% of electricity generation in the UK overall. This was unchanged from a year earlier.

Methodology

The figures in the article are from Carbon Brief analysis of data from DESNZ Energy Trends, chapter 5 and chapter 6, as well as from NESO. The figures from NESO are for electricity supplied to the grid in Great Britain only and are adjusted here to include Northern Ireland.

In Carbon Brief’s analysis, the NESO numbers are also adjusted to account for electricity used by power plants on site and for generation by plants not connected to the high-voltage national grid.

NESO already includes estimates for onshore windfarms, but does not cover industrial gas combined heat and power plants and those burning landfill gas, waste or sewage gas.

Carbon intensity figures from 2009 onwards are taken directly from NESO. Pre-2009 estimates are based on the NESO methodology, taking account of fuel use efficiency for earlier years.

The carbon intensity methodology accounts for lifecycle emissions from biomass. It includes emissions for imported electricity, based on the daily electricity mix in the country of origin.

DESNZ historical electricity data, including years before 2009, is adjusted to align with other figures and combined with data on imports from a separate DESNZ dataset. Note that the data prior to 1951 only includes “major” power producers.

The post Analysis: UK renewables enjoy record year in 2025 – but gas power still rises appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: UK renewables enjoy record year in 2025 – but gas power still rises

Greenhouse Gases

Ricky Bradley named Citizens’ Climate Executive Director after strategic and legislative progress during interim leadership role

Ricky Bradley named Citizens’ Climate Executive Director after strategic and legislative progress during interim leadership role

Dec. 22, 2025 – After a six month interim period, Ricky Bradley has been appointed Executive Director of Citizens’ Climate Lobby and Citizens’ Climate Education. The decision was made by the CCL and CCE boards of directors in a unanimous vote during their final joint board meeting of 2025.

Dec. 22, 2025 – After a six month interim period, Ricky Bradley has been appointed Executive Director of Citizens’ Climate Lobby and Citizens’ Climate Education. The decision was made by the CCL and CCE boards of directors in a unanimous vote during their final joint board meeting of 2025.

“Citizens’ Climate Lobby is fortunate to have someone with Ricky Bradley’s experience, commitment, and demeanor to lead the organization,” said CCL board chair Bill Blancato. “I can’t think of anyone with as much knowledge about CCL and its mission who is held in such high regard by CCL’s staff and volunteers.”

Bradley has been active with Citizens’ Climate for more than 13 years. Prior to his former roles as Interim Executive Director and Vice President of Field Operations, he has also served as a volunteer Group Leader and volunteer Regional Coordinator, all of which ground him in Citizens’ Climate’s grassroots model. Bradley has also led strategic planning and implementation efforts at HSBC, helping a large team adopt new approaches and deliver on big organizational goals.

“We are confident that Ricky has the skills to guide CCL during a challenging time for organizations trying to make a difference on climate change,” Blancato added.

Since stepping into the Interim Executive Director role in July 2025, Bradley has led Citizens’ Climate through a season of high volunteer engagement and effective advocacy on Capitol Hill. Under his leadership, CCL staff and volunteers organized a robust virtual lobby week with 300+ constituent meetings, despite an extended government shutdown, and executed a targeted mobilization to support the bipartisan passage of climate-friendly forestry legislation through the Senate Agriculture Committee.

“We have heard nothing but glowing descriptions of Ricky’s ability as a leader, as a manager, and as a team player,” said CCE board chair Dr. Sandra Kirtland Turner. “We’ve been absolutely thrilled with how Ricky’s brought the team together over the last six months to deliver on a new strategic plan for the organization.”

The strategic plan, which launched during CCL’s Fall Conference in November, details Citizens’ Climate’s unique role in the climate advocacy space, its theory of change for effectively moving federal climate legislation forward, and its strategic goals for 2026.

“Ricky has the heart of a CCLer and the strategic chops to take us into the next chapter as an organization,” Dr. Kirtland Turner said.

Bradley shared his vision for that next chapter in his conference opening remarks last month and, most recently, during the organization’s December monthly meeting.

“There’s a lot that we don’t control in today’s politics, but we do know who we are. The power of our persistent, nonpartisan advocacy is unmistakable,” Bradley said. “If we stay true to that, deepen our skills, and walk forward together, I know we’re going to meet this moment and deliver real results for the climate.”

CONTACT: Flannery Winchester, CCL Vice President of Marketing and Communications, 615-337-3642, flannery@citizensclimate.org

###

Citizens’ Climate Lobby is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, grassroots advocacy organization focused on national policies to address climate change. Learn more at citizensclimatelobby.org.

The post Ricky Bradley named Citizens’ Climate Executive Director after strategic and legislative progress during interim leadership role appeared first on Citizens' Climate Lobby.

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 19 December 2025: EU’s petrol car U-turn; Trump to axe ‘leading’ research lab; What climate scientists are reading

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

EU easing up

HITTING THE BREAKS: The EU “walked back” its target to ban the sale of petrol and diesel cars by 2035, “permitting some new combustion engine cars”, reported Agence-France Presse. Under the original plan, the bloc would have had to cut emissions entirely by 2035 on new vehicles, but will now only have to cut emissions by 90% by that date, compared to 2021 levels. However, according to the Financial Times, some car manufacturers have “soured” on the reversal.

ADJUSTING CBAM: Meanwhile, the Financial Times reported that the EU is making plans to “close loopholes” in the bloc’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) before it goes into effect in January. CBAM is set to be the world’s first carbon border tax and has drawn ire from key trading partners. The EU has also finalised a plan to delay its anti-deforestation legislation for another year, according to Carbon Pulse.

Around the world

- NCAR NO MORE: The Trump administration is moving to “dismantle” the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado, said USA Today, describing it as “one of the world’s leading climate research labs”.

- DEADLY FLOODS: The deadliest flash flooding in Morocco in a decade killed “at least” 37 people, while residents accused the government of “ignoring known flood risks and failing to maintain basic infrastructure”, reported Radio France Internationale.

- FAILING GRADE: The past year was the “warmest and wettest” ever recorded in the Arctic, with implications for “global sea level rise, weather patterns and commercial fisheries”, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s 2025 Arctic report card, covered by NPR.

- POWER TO THE PEOPLE: Reuters reported that Kenya signed a $311m agreement with an African infrastructure fund and India’s Power Grid Corporation for the “construction of two high-voltage electricity transmission lines” that could provide power for millions of people.

- BP’S NEW EXEC: BP has appointed Woodside Energy Group’s Meg O’Neill as its new chief executive amid a “renewed push to…double down on oil and gas after retreating from an ambitious renewables strategy”, said Reuters.

29

The number of consecutive years in which the Greenland ice sheet has experienced “continuous annual ice loss”, according to a Carbon Brief guest post.

Latest climate research

- Up to 4,000 glaciers could “disappear” per year during “peak glacier extinction”, projected to occur sometime between 2041 and 2055 | Nature Climate Change

- The rate of sea level rise across the coastal US doubled over the past century | AGU Advances

- Repression and criminalisation of climate and environmentally focused protests are a “global phenomena”, according to an analysis of 14 countries | Environmental Politics

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The latest coal market report from the International Energy Agency said that global coal use will reach record levels in 2025, but will decline by the end of the decade. Carbon Brief analysis of the report found that projected coal use in China for 2027 has been revised downwards by 127m tonnes, compared to the projection from the 2024 report – “more than cancelling out the effects of the Trump administration’s coal-friendly policies in the US”.

Spotlight

What climate scientists are curious about

This week, Carbon Brief spoke to climate scientists attending the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in New Orleans, Louisiana, about the most interesting research papers they read this year.

Their answers have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Dr Christopher Callahan, assistant professor at Indiana University Bloomington

The most interesting research paper I read was a simple thought experiment asking when we would have known humans were changing the climate if we had always had perfect observations. The authors show that we could have detected a human influence on the climate as early as the 1880s, since we have a strong physical understanding of how those changes should look. This paper both highlights that we have been discernibly changing the climate for centuries and emphasises the importance of the modern climate observing network – a network that is currently threatened by budget cuts and staff shortages.

Prof Lucy Hutyra, distinguished professor at Boston University

The most interesting paper I read was in Nature Climate Change, where the researchers looked at how much mortality was associated with cold weather versus hot weather events and found that many more people died during cold weather events. Then, they estimated how much of a protective factor in the urban heat island is on those winter deaths and suggested that the winter benefits exceed the summer risks of mitigating extreme heat, so perhaps we shouldn’t mitigate extreme heat in cities.

This paper got me in a tizzy…It spurred an exciting new line of research. We’ll be publishing a response to this paper in 2026. I’m not sure their conclusion was correct, but it raised really excellent questions.

Dr Kristina Dahl, vice president for science at Climate Central

This year was when we saw source attribution studies, such as Chris Callahan‘s, really start to break through and be able to connect the emissions of specific emitters…to the impact of those emissions through heat or some other sort of damage function. [This] is really game-changing.

What [Callahan’s] paper showed is that the emissions of individual companies have an impact on extreme heat, which then has an impact on the GDP of the countries experiencing that extreme heat. And so, for the first time, you can really say: “Company X caused this condition which then led to this economic damage.”

Dr Antonia Hadjimichael, assistant professor at Pennsylvania State University

It was about interdisciplinary work – not that anything in it is ground-shakingly new, but it was a good conversation around interdisciplinary teams and what makes them work and what doesn’t make them work. And what I really liked about it is that they really emphasise the role of a connector – the scientist that navigates this space in between and makes sure that the things kind of glue together…The reason I really like this paper is that we don’t value those scientists in academia, in traditional metrics that we have.

Dr Santiago Botía, researcher at Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry

The most interesting paper I’ve read this year was about how soil fertility and water table depth control the response to drought in the Amazon. They found very nicely how the proximity to soil water controls the anomalies in gross primary productivity in the Amazon. And, with that methodology, they could explain the response of recent droughts and the “greening” of the forest during drought, which is kind of a counterintuitive [phenomenon], but it was very interesting.

Dr Gregory Johnson, affiliate professor at the University of Washington

This article explores the response of a fairly coarse spatial resolution climate model…to a scenario in which atmospheric CO2 is increased at 1% a year to doubling and then CO2 is more gradually removed from the atmosphere…[It finds] a large release of heat from the Southern Ocean, with substantial regional – and even global – climate impacts. I find this work interesting because it reminds us of the important – and potentially nonlinear – roles that changing ocean circulation and water properties play in modulating our climate.

Cecilia Keating also contributed to this spotlight.

Watch, read, listen

METHANE MATTERS: In the Guardian, Barbados prime minister Mia Mottley wrote that the world must “urgently target methane” to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

CLIMATE WRAPPED: Grist summarised the major stories for Earth’s climate in 2025 – “the good, the bad and the ugly”.

COASTING: On the Coastal Call podcast, a biogeochemist spoke about “coastal change and community resilience” in the eastern US’s Long Island Sound.

Coming up

- 27 December: Cote D’Ivoire parliamentary elections

- 28 December: Central African Republic presidential and parliamentary elections

- 28 December: Guinean presidential election

Pick of the jobs

- BirdLife International, forest programme administrator | Salary: £28,000-£30,000. Location: Cambridge, UK

- World Resources Institute, power-sector transition senior manager | Salary: $116,000-$139,000. Location: Washington DC

- Fauna & Flora, operations lead for Liberia | Salary: $61,910. Location: Monrovia, Liberia

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 19 December 2025: EU’s petrol car U-turn; Trump to axe ‘leading’ research lab; What climate scientists are reading appeared first on Carbon Brief.

-

Climate Change5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval