China has seen a series of temperature records broken this summer, as heatwaves have struck various regions across the country.

Between mid-March and mid-July 2025, it was hit by an unprecedented number of “hot days” – where temperatures reach or exceed 35C – according to the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) .

In both May and June, heatwaves swept across northern regions, with temperatures in Xinjiang reaching as high as 46.8C.

Such a record-breaking summer is becoming increasingly common, with the CMA’s annual Climate Bulletins showing that hundreds of local heat records have been surpassed over the past decade.

The CMA says that “extreme high temperatures” have shown an “increasing trend” in China since its records began in 1961.

Experts tell Carbon Brief that heatwaves strongly affect public health, agricultural output and economic activity.

They also put significant strain on the electricity system.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief looks at how heat extremes are changing in China, the role of climate change in making these worse and how the country is adapting to the impacts.

How are heat extremes changing in China?

The latest science report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that it is “virtually certain” that “the frequency and intensity of hot extremes have increased” across the world since 1950.

The IPCC adds that it is “virtually certain” that human-caused greenhouse gas emissions are “the main driver”.

China is no exception. In a press release for its latest 2025 “blue book on climate change in China”, the CMA says China is “susceptible to the impacts of global climate change”, noting:

“[China’s] warming rate is higher than the global average…and extreme weather and climate events are becoming more frequent and intense.”

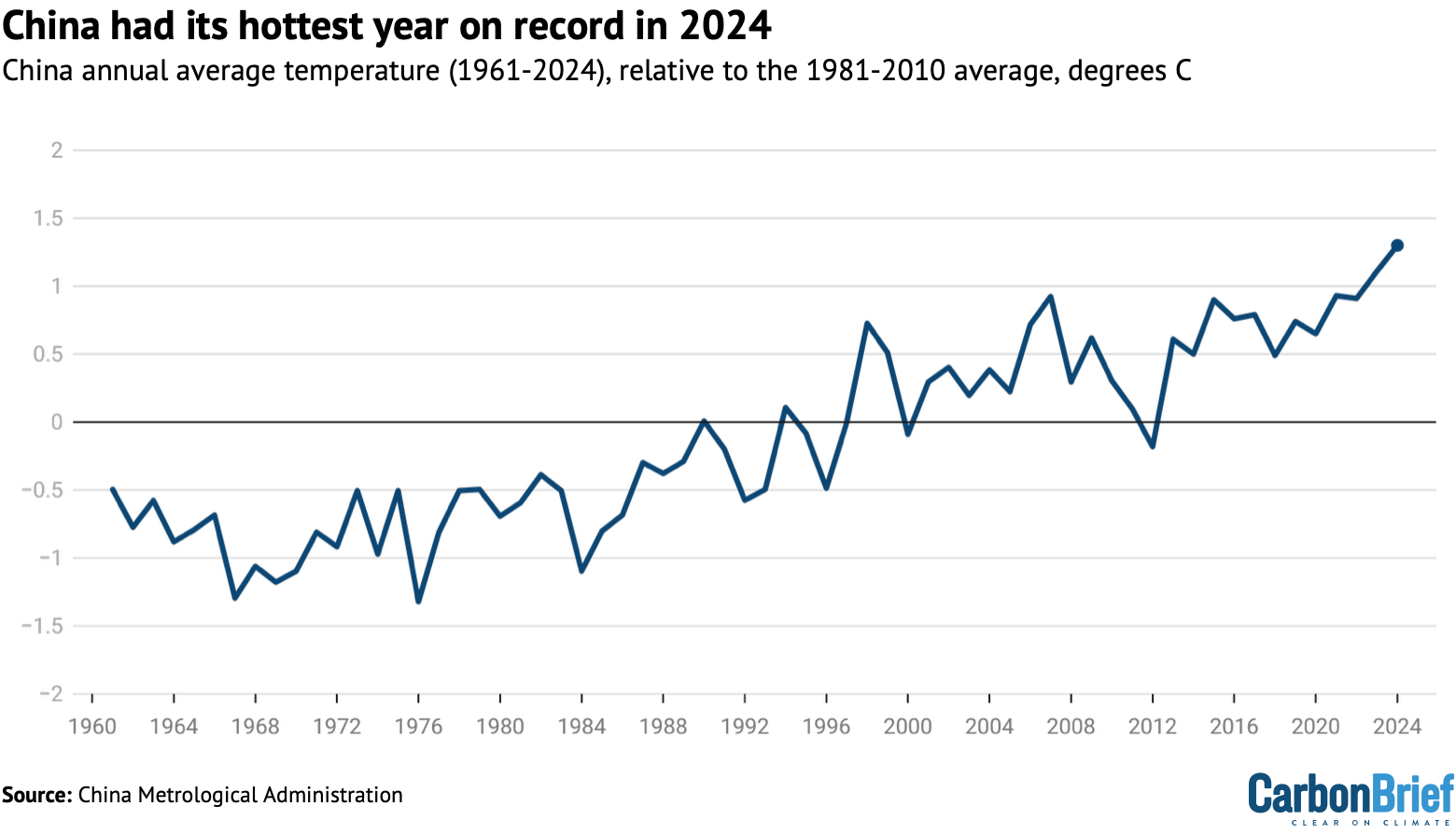

Data from the CMA’s Climate Bulletins show how the average annual temperature in China is rising and how 2024 was the hottest year on record, as shown in the chart below.

While 2024 was the hottest year on record overall, this was a result of consistently high temperatures throughout the seasons.

At a CMA press conference in 2025, Chan Xiao, deputy director of the CMA commented:

“Temperatures were consistently high throughout the year, with significant fluctuations in temperature during winter. Spring, summer and autumn temperatures were all record highs for the same period.”

In contrast, more heat records were broken during 2022, even though it was not quite as hot overall. Explaining this, Prof Yang Chen from Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, which falls under the CMA, tells Carbon Brief:

“[For] the annual mean air temperatures, every day counts. So even if the 2022 was exceptional for its large number – actually also very long duration-consecutive days and high-magnitude – of hot extremes, mainly during summer and in the Yangtze River Valley, it does not mean the remaining days were hotter than the counterparts in 2024.”

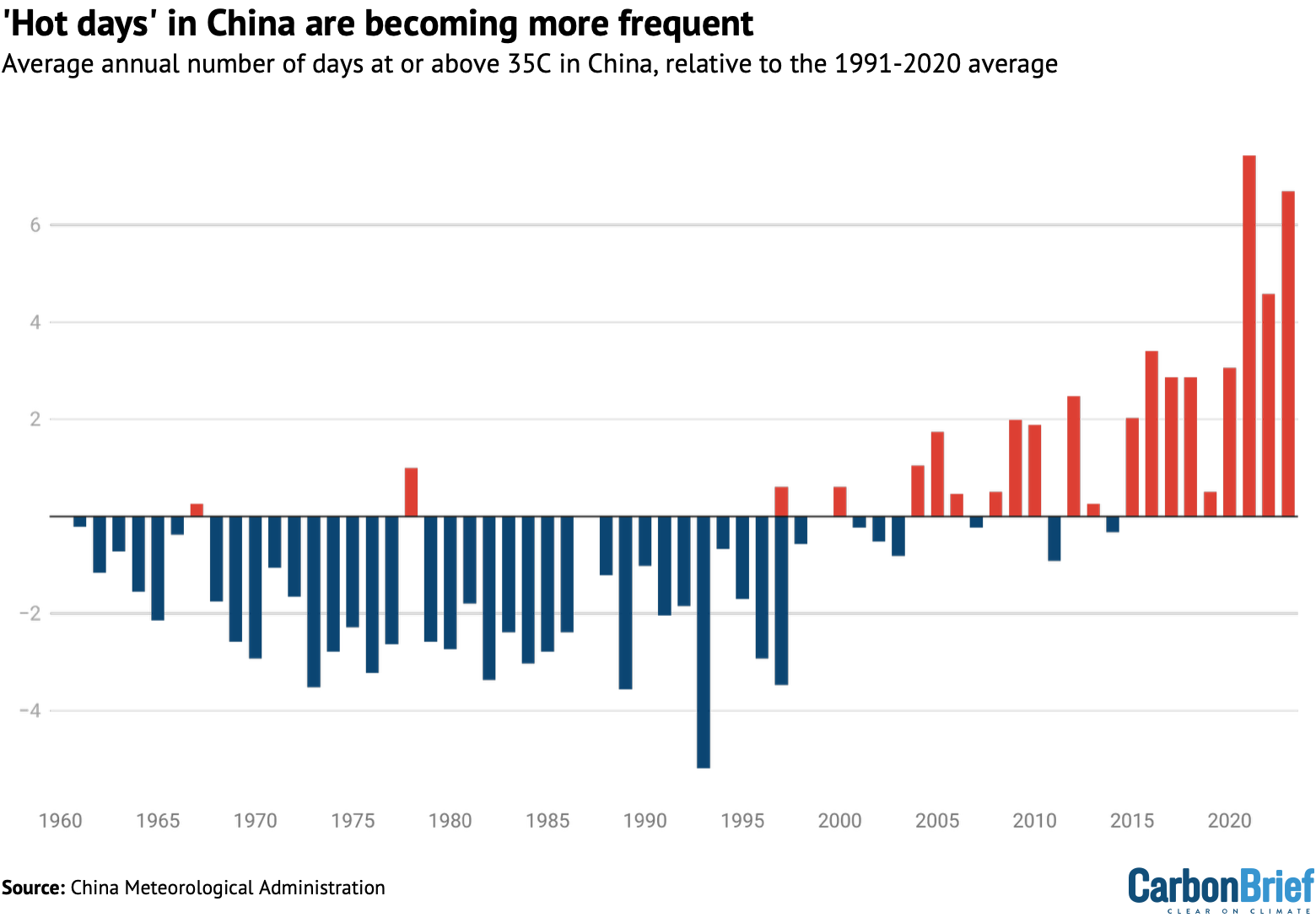

The CMA defines a “hot day” or “high temperature day” as one that reaches or exceeds 35C. It adds that “high temperatures for several consecutive days constitute a heatwave”.

As the global climate has warmed, the number of “hot days” that China is experiencing has been on the rise, shown in the figure below.

The year 2022 set a new record, with meteorological stations in China recording an average of 16.4 hot days. This was 7.3 more than the average for 1991-2020. The year 2024 came close to this record, with 15.6 hot days. These two years have also seen China’s hottest summers on record.

In 2022, more than 1,000 meteorological stations in China reported heatwaves, with 441 breaking “historical records”. For 2024, 74 stations reported “consecutive high temperature days” and 81 of them broke records.

Xiao said at a press conference in 2023 that “continuous high temperatures” in China’s central and eastern regions lasted for 79 days in the summer of 2022. The provinces of Gansu and Xinjiang in north-west China, Hubei in central China and Sichuan in south-west China all reported their “highest temperatures since 1961”.

In addition, the “maximum daily temperature [in the summer of 2022] at 361 national meteorological stations – accounting for 14.9% of the total number of stations in the country – reached or exceeded historical extremes”, Xiao added.

The CMA has also highlighted that summer is arriving earlier for much of China. In 2024, for example, summer in regions including most of Hainan province in south China, central Yunnan province in south-west China as well as central and southern Xinjiang province in north-west China arrived more than 20 days earlier than average.

“If a year’s spring and summer are longer, the potential heatwaves…will also be longer,” Prof Wenjia Cai, from the department of earth system science of Tsinghua University, tells Carbon Brief.

Cai notes that there are more ways to define heatwaves than CMA’s absolute threshold of 35C.

For example, a heatwave can also be defined by how long the hot weather persists, or based on “the daily maximum temperature, daily average temperature, or even nighttime temperature”, she tells Carbon Brief.

However, regardless of the definition used, the “number of heatwave days is definitely increasing as a result of climate change”, she adds.

What role does human-caused climate change play?

A field of climate science called “attribution” has emerged over the past two decades to establish the role that human-caused warming plays in individual extreme weather events, including heatwaves, floods, droughts and storms.

Attribution studies can also be used to find the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change in longer-term trends, such as the gradual increase in surface temperatures over multiple decades.

Heat is the most-studied extreme event in attribution literature, as it is mainly driven by thermodynamic influences – in other words, it is relatively easy to study.

In contrast, storms and droughts are more strongly affected by complex atmospheric dynamics and, as such, can be trickier to simulate in a model. Cai tells Carbon Brief:

“High temperature is the most obvious trend against the background of climate change. Heatwaves, in comparison to events such as rainfall and typhoons, are also more predictable.”

Carbon Brief has produced an interactive map showing every attribution study published up to November 2024. In total, 114 extremes and trends in China have been the subject of an attribution study, including more than 20 relating specifically to extreme heat.

One study included on the map looks at the change in the intensity and frequency of extreme temperatures across China over 1951-2018. The authors say that, over this time period, “more intense and more frequent warm extremes” were observed across “most regions” in China – and that “greenhouse gas forcing plays a dominant role” in this.

Looking at individual extreme events, one analysis by the “rapid attribution” group World Weather Attribution investigates the then-record-breaking heat across China in July 2023. The analysis says that temperatures exceeded 50C in north-west China, adding that Sanbao, in Xinjiang, hit 52.2C on 16 July of that year.

The study finds that, in a world without climate change, such an extreme heat event would have been “extremely rare” and would only have happened once every 250 years. However, in today’s climate, as a result of human-caused climate change, a heatwave of this intensity is now expected once every five years.

This means China’s extreme heat of July 2023 was 50 times more likely due to climate change. The study also finds that in a world without climate change, the heatwave over China would have been 1C cooler.

A separate study finds that human-caused climate change also caused a more than 60-fold increase in the likelihood of the extremely warm 2013 summer, compared to the early 1950s.

It adds that other factors such as urbanisation and changes in atmospheric circulation patterns can also make heat extremes more intense and frequent.

What impact are these heatwaves having?

Heatwaves have a wide variety of impacts on human activities, such as public health, crop yields and economic output.

Older people are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat. The 2024 report from the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change found that, in 2023, demographic changes alone could have driven a 65% increase in heat-related deaths among over-65s, compared to the 1990-99 average.

Cai, who is also the lead author of the Lancet Countdown’s China report, tells Carbon Brief that older people are the “most commonly mentioned vulnerable group” and that the number of people affected by heatwaves will grow as societies age.

However, heatwaves also “affect outdoor activities” regardless of age group, she adds, as well as having impacts on sleep and allergies:

“We don’t want anyone to think they are in a group of people unaffected by heatwaves.”

Cai says that heat exposure can increase the incidence of certain dangerous behaviours, such as domestic violence, as well as a wide range of diseases – including cardiovascular diseases and respiratory diseases – and mental health disorders.

In 2023, more than 30,000 deaths were related to heatwaves in China – 1.9 times higher than the average over 1986-2005, according to Cai and her colleagues’ China report.

This was a result of increased heat exposure – the average number of “heatwave exposure days” per person reached 16 days in 2023, more than three times the historical average (1986-2005), the report adds.

A 2022 attribution study on China notes that extreme heat can also increase the risk of preterm births. The authors find that over 2010-20, an average of 13,262 premature births were recorded in China due to heatwave exposure. The study linked one-quarter of these early births to climate change.

Another profound impact of heatwaves is that they can exacerbate droughts, with knock-on impacts for agriculture.

Reuters reported last June that “China’s agriculture ministry said…searing temperatures have adversely impacted summer planting and that fighting drought and protecting summer planting were arduous tasks”.

Droughts in 2024 hit more than 11 million people in China, with more than 1.2m hectares of affected crops and direct economic losses topping nearly 8.4bn yuan ($1.2bn), the Ministry of Emergency Management said in early 2025.

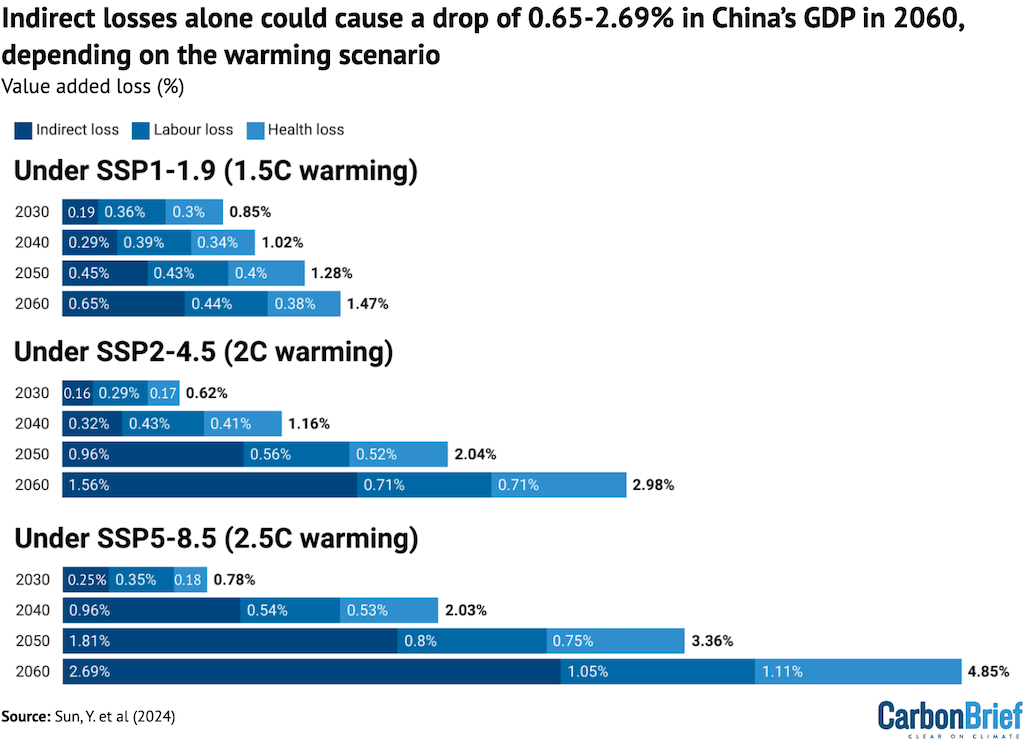

Heat-related economic losses could reach nearly 5% of China’s GDP by 2060, according to a recent guest post for Carbon Brief. Authors Prof Guan Dabo and doctoral student Sun Yida from Tsinghua University wrote:

“By 2060, China’s heat-induced economic losses could total about 1.5% of total GDP under 1.5C of global warming, 3% under 2C of warming and 4.9% under 2.5C of warming.”

Those predicted losses include “indirect economic losses”, which “could be due to changes in production, consumption or employment” in the global supply chain, including crop failures and labour slowdowns, they explained.

The figure below, based on their study, shows Chinese GDP losses under three different scenarios of future emissions, called “shared socioeconomic pathways” (SSPs).

The SSP1-1.9, SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios project average global temperature rises of around 1.5C, 2C and 2.5C by mid-century, respectively.

Economic losses are split into indirect losses (dark blue), labour losses (blue) and health losses (light blue).

Sectors such as the extractive industries, construction and non-metallic manufacturing “could see the highest losses” of about 4.6-6.4% of their “value-added” – the increase in worth of a product or service as it moves through different stages of production – largely because they are in Chinese “regions with significant warming”, according to Guan and Sun.

Those industries also have close business connections with south-east Asia, Africa and South America, which are “expected to face heightened exposure to production volatility caused by high temperatures”, they add.

The total economic loss globally could reach up to 4.6% by 2060, according to their study, and manufacturing-heavy countries such as China and the US, in particular, could be “strong[ly] hit”.

Other than manufacturing, electricity supplies in China have also been frequently reported to be affected by hot days.

Chinese news outlet China Business Network reports that China’s National Energy Administration said last year that summer was the hardest time to ensure sufficient electricity supply during a year and that extreme weather would make the supply even harder.

For 2025, China’s State Grid Corporation expected maximum electricity demand to exceed 1,200 gigawatts (GW), a new record.

Dr Muyi Yang, senior energy analyst at thinktank Ember, tells Carbon Brief that “when temperatures soar, electricity demand spikes – mainly due to air conditioning – and that can stretch the grid, especially in already tight systems”.

Biqing Yang, energy analyst at Ember, adds:

“In the third quarter of last year, for example, China’s residential electricity consumption rose significantly, by 17.8% year-on-year, largely due to elevated temperatures…It is clear that we are now entering an era [w]here climate change is having a real-time impact on our energy system.”

China’s electricity demand reached a new record in July 2025 after year-on-year growth of 8.6%, consuming more power in one month than Japan did in all of 2024, according to David Fishman, Shanghai-based principal at consultancy the Lantau Group.

The “staggering” July 2025 figures – including another 18% year-on-year rise in residential demand, partly due to rising household incomes, as well as air conditioning use – illustrates the impact of climate change on China’s power sector, Fishman writes on LinkedIn:

“We know it’s hot out and everyone knows every summer the intense heat seems to last for longer and longer. But these power consumption numbers are telling a story about China’s climate patterns like few other datasets can…and it’s a scary story.”

Yang, Chen and Cai tell Carbon Brief that it is important for China to adapt to the rising temperature and intensive heatwaves.

Chen specifically describes “successful” forecasts and early warnings as “critical” , saying that they are the “very first step toward adaptation”.

In his LinkedIn post, Fishman notes that the rapidly rising demand for electricity, including as a result of growing air conditioning use, also poses a “considerable challenge to China’s ability to meet rising demand solely with clean power sources”.

How is China adapting to heatwaves?

In recent years, China has implemented more and more policies aimed at adapting to heatwaves.

For example, weather forecasts and heatwave alerts have been provided.

Central and local governments have also issued labour policies aimed at protecting workers against extreme heat.

Under a policy from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, for instance, outdoor works are not expected to be undertaken when temperatures exceed 40C. In addition, outdoor working hours should be shorter than six hours when the temperature is 37-40C.

Similarly, school students in some cities, such as Wuhan and Chengdu, have been advised to study from home during hot days in recent years.

Since 2021, the city of Tianjian has been sending text warnings of heatwaves to its residents, reminding people of the health risks it poses. The messages, according to Southern Metropolis Daily, warn that strokes might be triggered in the coming hot days and advises people to avoid outdoor activities and take medication if needed.

These text reminders have “significantly” reduced the number of hospitalised people in Tianjin, saving the city 140m yuan ($19.5m) since being introduced, adds the outlet.

In 2013, the central government published its first “national climate change adaptation strategy” – an attempt to implement the “clear requirement” of “enhancing our ability to adapt to climate change” included in the 12th “five-year plan” (2011-15).

In the latest version for 2035, heatwaves appear in sections related to the power sector, as well as agriculture and health.

The strategy aims to “improve” and “reinforce” nationwide “labour protection standards”, as well as “work system[s] that adapt to change and reduce agricultural disasters”. Its purpose is also to ensure the energy and electricity sectors’ abilities to “withstand extreme weather and climate events” in relation to heatwaves.

The strategy says that “health-risk assessment guidelines” and public health-related “implementation plans for adaptation under major extreme weather and climate events”, such as heat and heatwaves,in “various regions”, will be developed.

Last year, following the release of the latest overall adaptation strategy, China published the “national climate change health adaptation action plan (2024-30)”.

Cai calls the document a “very very important” blueprint for health risk management, bringing together a range of organisations, including hospitals, to form a “system related to climate change and health” that has “monitoring and early warning capabilities”.

She adds that this plan will also see heat-health alerts being issued nationwide:

“It is worth mentioning that the National Administration of Disease Control and Prevention and the China Meteorological Administration signed a joint agreement [in May 2025] on issuing [nationwide] health alerts – and that the first product is related to heatwaves.”

Ember’s Yang says that in terms of electricity, China is moving toward building a “‘new electricity system (新型电力系统)’ that is more compatible with high shares of renewables”. But, he adds, the old “planning psychology” needs to change so that it can better cope with extreme heat:

“Traditionally, the mindset has been very supply-driven – just keep adding enough generation and network capacity to meet demand…[With the new system] the demand side has to become an active player – a prosumer – that can actually support grid reliability.

“For example, during extreme heat, instead of just ramping up supply, we should also be encouraging users to reduce or shift their electricity use during peak hours, using price signals or incentives…This is the essence of what we call ‘coordinating generation, grid, load, and storage’ (源网荷储一体化) – a system that works together [and works] more efficiently and flexibly.”

The post Q&A: How China is adapting to ‘more frequent and intense’ heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: How China is adapting to ‘more frequent and intense’ heat extremes

Greenhouse Gases

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Food inflation on the rise

DELUGE STRIKES FOOD: Extreme rainfall and flooding across the Mediterranean and north Africa has “battered the winter growing regions that feed Europe…threatening food price rises”, reported the Financial Times. Western France has “endured more than 36 days of continuous rain”, while farmers’ associations in Spain’s Andalusia estimate that “20% of all production has been lost”, it added. Policy expert David Barmes told the paper that the “latest storms were part of a wider pattern of climate shocks feeding into food price inflation”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

NO BEEF: The UK’s beef farmers, meanwhile, “face a double blow” from climate change as “relentless rain forces them to keep cows indoors”, while last summer’s drought hit hay supplies, said another Financial Times article. At the same time, indoor growers in south England described a 60% increase in electricity standing charges as a “ticking timebomb” that could “force them to raise their prices or stop production, which will further fuel food price inflation”, wrote the Guardian.

‘TINDERBOX’ AND TARIFFS: A study, covered by the Guardian, warned that major extreme weather and other “shocks” could “spark social unrest and even food riots in the UK”. Experts cited “chronic” vulnerabilities, including climate change, low incomes, poor farming policy and “fragile” supply chains that have made the UK’s food system a “tinderbox”. A New York Times explainer noted that while trade could once guard against food supply shocks, barriers such as tariffs and export controls – which are being “increasingly” used by politicians – “can shut off that safety valve”.

El Niño looms

NEW ENSO INDEX: Researchers have developed a new index for calculating El Niño, the large-scale climate pattern that influences global weather and causes “billions in damages by bringing floods to some regions and drought to others”, reported CNN. It added that climate change is making it more difficult for scientists to observe El Niño patterns by warming up the entire ocean. The outlet said that with the new metric, “scientists can now see it earlier and our long-range weather forecasts will be improved for it.”

WARMING WARNING: Meanwhile, the US Climate Prediction Center announced that there is a 60% chance of the current La Niña conditions shifting towards a neutral state over the next few months, with an El Niño likely to follow in late spring, according to Reuters. The Vibes, a Malaysian news outlet, quoted a climate scientist saying: “If the El Niño does materialise, it could possibly push 2026 or 2027 as the warmest year on record, replacing 2024.”

CROP IMPACTS: Reuters noted that neutral conditions lead to “more stable weather and potentially better crop yields”. However, the newswire added, an El Niño state would mean “worsening drought conditions and issues for the next growing season” to Australia. El Niño also “typically brings a poor south-west monsoon to India, including droughts”, reported the Hindu’s Business Line. A 2024 guest post for Carbon Brief explained that El Niño is linked to crop failure in south-eastern Africa and south-east Asia.

News and views

- DAM-AG-ES: Several South Korean farmers filed a lawsuit against the country’s state-owned utility company, “seek[ing] financial compensation for climate-related agricultural damages”, reported United Press International. Meanwhile, a national climate change assessment for the Philippines found that the country “lost up to $219bn in agricultural damages from typhoons, floods and droughts” over 2000-10, according to Eco-Business.

- SCORCHED GRASS: South Africa’s Western Cape province is experiencing “one of the worst droughts in living memory”, which is “scorching grass and killing livestock”, said Reuters. The newswire wrote: “In 2015, a drought almost dried up the taps in the city; farmers say this one has been even more brutal than a decade ago.”

- NOUVELLE VEG: New guidelines published under France’s national food, nutrition and climate strategy “urged” citizens to “limit” their meat consumption, reported Euronews. The delayed strategy comes a month after the US government “upended decades of recommendations by touting consumption of red meat and full-fat dairy”, it noted.

- COURTING DISASTER: India’s top green court accepted the findings of a committee that “found no flaws” in greenlighting the Great Nicobar project that “will lead to the felling of a million trees” and translocating corals, reported Mongabay. The court found “no good ground to interfere”, despite “threats to a globally unique biodiversity hotspot” and Indigenous tribes at risk of displacement by the project, wrote Frontline.

- FISH FALLING: A new study found that fish biomass is “falling by 7.2% from as little as 0.1C of warming per decade”, noted the Guardian. While experts also pointed to the role of overfishing in marine life loss, marine ecologist and study lead author Dr Shahar Chaikin told the outlet: “Our research proves exactly what that biological cost [of warming] looks like underwater.”

- TOO HOT FOR COFFEE: According to new analysis by Climate Central, countries where coffee beans are grown “are becoming too hot to cultivate them”, reported the Guardian. The world’s top five coffee-growing countries faced “57 additional days of coffee-harming heat” annually because of climate change, it added.

Spotlight

Nature talks inch forward

This week, Carbon Brief covers the latest round of negotiations under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which occurred in Rome over 16-19 February.

The penultimate set of biodiversity negotiations before October’s Conference of the Parties ended in Rome last week, leaving plenty of unfinished business.

The CBD’s subsidiary body on implementation (SBI) met in the Italian capital for four days to discuss a range of issues, including biodiversity finance and reviewing progress towards the nature targets agreed under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

However, many of the major sticking points – particularly around finance – will have to wait until later this summer, leaving some observers worried about the capacity for delegates to get through a packed agenda at COP17.

The SBI, along with the subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) will both meet in Nairobi, Kenya, later this summer for a final round of talks before COP17 kicks off in Yerevan, Armenia, on 19 October.

Money talks

Finance for nature has long been a sticking point at negotiations under the CBD.

Discussions on a new fund for biodiversity derailed biodiversity talks in Cali, Colombia, in autumn 2024, requiring resumed talks a few months later.

Despite this, finance was barely on the agenda at the SBI meetings in Rome. Delegates discussed three studies on the relationship between debt sustainability and implementation of nature plans, but the more substantive talks are set to take place at the next SBI meeting in Nairobi.

Several parties “highlighted concerns with the imbalance of work” on finance between these SBI talks and the next ones, reported Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Lim Li Ching, senior researcher at Third World Network, noted that tensions around finance permeated every aspect of the talks. She told Carbon Brief:

“If you’re talking about the gender plan of action – if there’s little or no financial resources provided to actually put it into practice and implement it, then it’s [just] paper, right? Same with the reporting requirements and obligations.”

Monitoring and reporting

Closely linked to the issue of finance is the obligations of parties to report on their progress towards the goals and targets of the GBF.

Parties do so through the submission of national reports.

Several parties at the talks pointed to a lack of timely funding for driving delays in their reporting, according to ENB.

A note released by the CBD Secretariat in December said that no parties had submitted their national reports yet; by the time of the SBI meetings, only the EU had. It further noted that just 58 parties had submitted their national biodiversity plans, which were initially meant to be published by COP16, in October 2024.

Linda Krueger, director of biodiversity and infrastructure policy at the environmental not-for-profit Nature Conservancy, told Carbon Brief that despite the sparse submissions, parties are “very focused on the national report preparation”. She added:

“Everybody wants to be able to show that we’re on the path and that there still is a pathway to getting to 2030 that’s positive and largely in the right direction.”

Watch, read, listen

NET LOSS: Nigeria’s marine life is being “threatened” by “ghost gear” – nets and other fishing equipment discarded in the ocean – said Dialogue Earth.

COMEBACK CAUSALITY: A Vox long-read looked at whether Costa Rica’s “payments for ecosystem services” programme helped the country turn a corner on deforestation.

HOMEGROWN GOALS: A Straits Times podcast discussed whether import-dependent Singapore can afford to shelve its goal to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030.

‘RUSTING’ RIVERS: The Financial Times took a closer look at a “strange new force blighting the [Arctic] landscape”: rivers turning rust-orange due to global warming.

New science

- Lakes in the Congo Basin’s peatlands are releasing carbon that is thousands of years old | Nature Geoscience

- Natural non-forest ecosystems – such as grasslands and marshlands – were converted for agriculture at four times the rate of land with tree cover between 2005 and 2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Around one-quarter of global tree-cover loss over 2001-22 was driven by cropland expansion, pastures and forest plantations for commodity production | Nature Food

In the diary

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean | Brasília

- 5 March: Nepal general elections

- 9-20 March: First part of the thirty-first session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) | Kingston, Jamaica

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

Greenhouse Gases

Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’

Rising temperatures across France since the mid-1970s is putting Tour de France competitors at “high risk”, according to new research.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, uses 50 years of climate data to calculate the potential heat stress that athletes have been exposed to across a dozen different locations during the world-famous cycling race.

The researchers find that both the severity and frequency of high-heat-stress events have increased across France over recent decades.

But, despite record-setting heatwaves in France, the heat-stress threshold for safe competition has rarely been breached in any particular city on the day the Tour passed through.

(This threshold was set out by cycling’s international governing body in 2024.)

However, the researchers add it is “only a question of time” until this occurs as average temperatures in France continue to rise.

The lead author of the study tells Carbon Brief that, while the race organisers have been fortunate to avoid major heat stress on race days so far, it will be “harder and harder to be lucky” as extreme heat becomes more common.

‘Iconic’

The Tour de France is one of the world’s most storied cycling races and the oldest of Europe’s three major multi-week cycling competitions, or Grand Tours.

Riders cover around 3,500 kilometres (km) of distance and gain up to nearly 55km of altitude over 21 stages, with only two or three rest days throughout the gruelling race.

The researchers selected the Tour de France because it is the “iconic bike race. It is the bike race of bike races,” says Dr Ivana Cvijanovic, a climate scientist at the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development, who led the new work.

Heat has become a growing problem for the competition in recent years.

In 2022, Alexis Vuillermoz, a French competitor, collapsed at the finish line of the Tour’s ninth stage, leaving in an ambulance and subsequently pulling out of the race entirely.

Two years later, British cyclist Sir Mark Cavendish vomited on his bike during the first stage of the race after struggling with the 36C heat.

The Tour also makes a good case study because it is almost entirely held during the month of July and, while the route itself changes, there are many cities and stages that are repeated from year to year, Cvijanovic adds.

‘Have to be lucky’

The study focuses on the 50-year span between 1974 and 2023.

The researchers select six locations across the country that have commonly hosted the Tour, from the mountain pass of Col du Tourmalet, in the French Pyrenees, to the city of Paris – where the race finishes, along the Champs-Élysées.

These sites represent a broad range of climatic zones: Alpe d’ Huez, Bourdeaux, Col du Tourmalet, Nîmes, Paris and Toulouse.

For each location, they use meteorological reanalysis data from ERA5 and radiant temperature data from ERA5-HEAT to calculate the “wet-bulb globe temperature” (WBGT) for multiple times of day across the month of July each year.

WBGT is a heat-stress index that takes into account temperature, humidity, wind speed and direct sunlight.

Although there is “no exact scientific consensus” on the best heat-stress index to use, WBGT is “one of the rare indicators that has been originally developed based on the actual human response to heat”, Cvijanovic explains.

It is also the one that the International Cycling Union (UCI) – the world governing body for sport cycling – uses to assess risk. A WBGT of 28C or higher is classified as “high risk” by the group.

WBGT is the “gold standard” for assessing heat stress, says Dr Jessica Murfree, director of the ACCESS Research Laboratory and assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Murfree, who was not involved in the new study, adds that the researchers are “doing the right things by conducting their science in alignment with the business practices that are already happening”.

The researchers find that across the 50-year time period, WBGT has been increasing across the entire country – albeit, at different rates. In the north-west of the country, WBGT has increased at an average rate of 0.1C per decade, while in the southern and eastern parts of the country, it has increased by more than 0.5C per decade.

The maps below show the maximum July WBGT for each decade of the analysis (rows) and for hourly increments of the late afternoon (columns). Lower temperatures are shown in lighter greens and yellows, while higher temperatures are shown in darker reds and purples.

Six Tour de France locations analysed in the study are shown as triangles on the maps (clockwise from top): Paris, Alpe d’ Huez, Nîmes, Toulouse, Col du Tourmalet and Bordeaux.

The maps show that the maximum WBGT temperature in the afternoon has surpassed 28C over almost the entire country in the last decade. The notable exceptions to this are the mountainous regions of the Alps and the Pyrenees.

The researchers also find that most of the country has crossed the 28C WBGT threshold – which they describe as “dangerous heat levels” – on at least one July day over the past decade. However, by looking at the WBGT on the day the Tour passed through any of these six locations, they find that the threshold has rarely been breached during the race itself.

For example, the research notes that, since 1974, Paris has seen a WBGT of 28C five times at 3pm in July – but that these events have “so far” not coincided with the cycling race.

The study states that it is “fortunate” that the Tour has so far avoided the worst of the heat-stress.

Cvijanovic says the organisers and competitors have been “lucky” to date. She adds:

“It has worked really well for them so far. But as the frequency of these [extreme heat] events is increasing, it will be harder and harder to be lucky.”

Dr Madeleine Orr, an assistant professor of sport ecology at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that the paper was “really well done”, noting that its “methods are good [and its] approach was sound”. She adds:

“[The Tour has] had athletes complain about [the heat]. They’ve had athletes collapse – and still those aren’t the worst conditions. I think that that says a lot about what we consider safe. They’ve still been lucky to not see what unsafe looks like, despite [the heat] having already had impacts.”

Heat safety protocols

In 2024, the UCI set out its first-ever high temperature protocol – a set of guidelines for race organisers to assess athletes’ risk of heat stress.

The assessment places the potential risk into one of five categories based on the WBGT, ranging from very low to high risk.

The protocol then sets out suggested actions to take in the event of extreme heat, ranging from having athletes complete their warm-ups using ice vests and cold towels to increasing the number of support vehicles providing water and ice.

If the WBGT climbs above the 28C mark, the protocol suggests that organisers modify the start time of the stage, adapt the course to remove particularly hazardous sections – or even cancel the race entirely.

However, Orr notes that many other parts of the race, such as spectator comfort and equipment functioning, may have lower temperatures thresholds that are not accounted for in the protocol, but should also be considered.

Murfree points out that the study’s findings – and the heat protocol itself – are “really focused on adaptation, rather than mitigation”. While this is “to be expected”, she tells Carbon Brief:

“Moving to earlier start times or adjusting the route specifically to avoid these locations that score higher in heat stress doesn’t stop the heat stress. These aren’t climate preventative measures. That, I think, would be a much more difficult conversation to have in the research because of the Tour de France’s intimate relationship with fossil-fuel companies.”

The post Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Preparing for 3C

NEW ALERT: The EU’s climate advisory board urged countries to prepare for 3C of global warming, reported the Guardian. The outlet quoted Maarten van Aalst, a member of the advisory board, saying that adapting to this future is a “daunting task, but, at the same time, quite a doable task”. The board recommended the creation of “climate risk assessments and investments in protective measures”.

‘INSUFFICIENT’ ACTION: EFE Verde added that the advisory board said that the EU’s adaptation efforts were so far “insufficient, fragmented and reactive” and “belated”. Climate impacts are expected to weaken the bloc’s productivity, put pressure on public budgets and increase security risks, it added.

UNDERWATER: Meanwhile, France faced “unprecedented” flooding this week, reported Le Monde. The flooding has inundated houses, streets and fields and forced the evacuation of around 2,000 people, according to the outlet. The Guardian quoted Monique Barbut, minister for the ecological transition, saying: “People who follow climate issues have been warning us for a long time that events like this will happen more often…In fact, tomorrow has arrived.”

IEA ‘erases’ climate

MISSING PRIORITY: The US has “succeeded” in removing climate change from the main priorities of the International Energy Agency (IEA) during a “tense ministerial meeting” in Paris, reported Politico. It noted that climate change is not listed among the agency’s priorities in the “chair’s summary” released at the end of the two-day summit.

US INTERVENTION: Bloomberg said the meeting marked the first time in nine years the IEA failed to release a communique setting out a unified position on issues – opting instead for the chair’s summary. This came after US energy secretary Chris Wright gave the organisation a one-year deadline to “scrap its support of goals to reduce energy emissions to net-zero” – or risk losing the US as a member, according to Reuters.

Around the world

- ISLAND OBJECTION: The US is pressuring Vanuatu to withdraw a draft resolution supporting an International Court of Justice ruling on climate change, according to Al Jazeera.

- GREENLAND HEAT: The Associated Press reported that Greenland’s capital Nuuk had its hottest January since records began 109 years ago.

- CHINA PRIORITIES: China’s Energy Administration set out its five energy priorities for 2026-2030, including developing a renewable energy plan, said International Energy Net.

- AMAZON REPRIEVE: Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has continued to fall into early 2026, extending a downward trend, according to the latest satellite data covered by Mongabay.

- GEZANI DESTRUCTION: Reuters reported the aftermath of the Gezani cyclone, which ripped through Madagascar last week, leaving 59 dead and more than 16,000 displaced people.

20cm

The average rise in global sea levels since 1901, according to a Carbon Brief guest post on the challenges in projecting future rises.

Latest climate research

- Wildfire smoke poses negative impacts on organisms and ecosystems, such as health impacts on air-breathing animals, changes in forests’ carbon storage and coral mortality | Global Ecology and Conservation

- As climate change warms Antarctica throughout the century, the Weddell Sea could see the growth of species such as krill and fish and remain habitable for Emperor penguins | Nature Climate Change

- About 97% of South American lakes have recorded “significant warming” over the past four decades and are expected to experience rising temperatures and more frequent heatwaves | Climatic Change

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

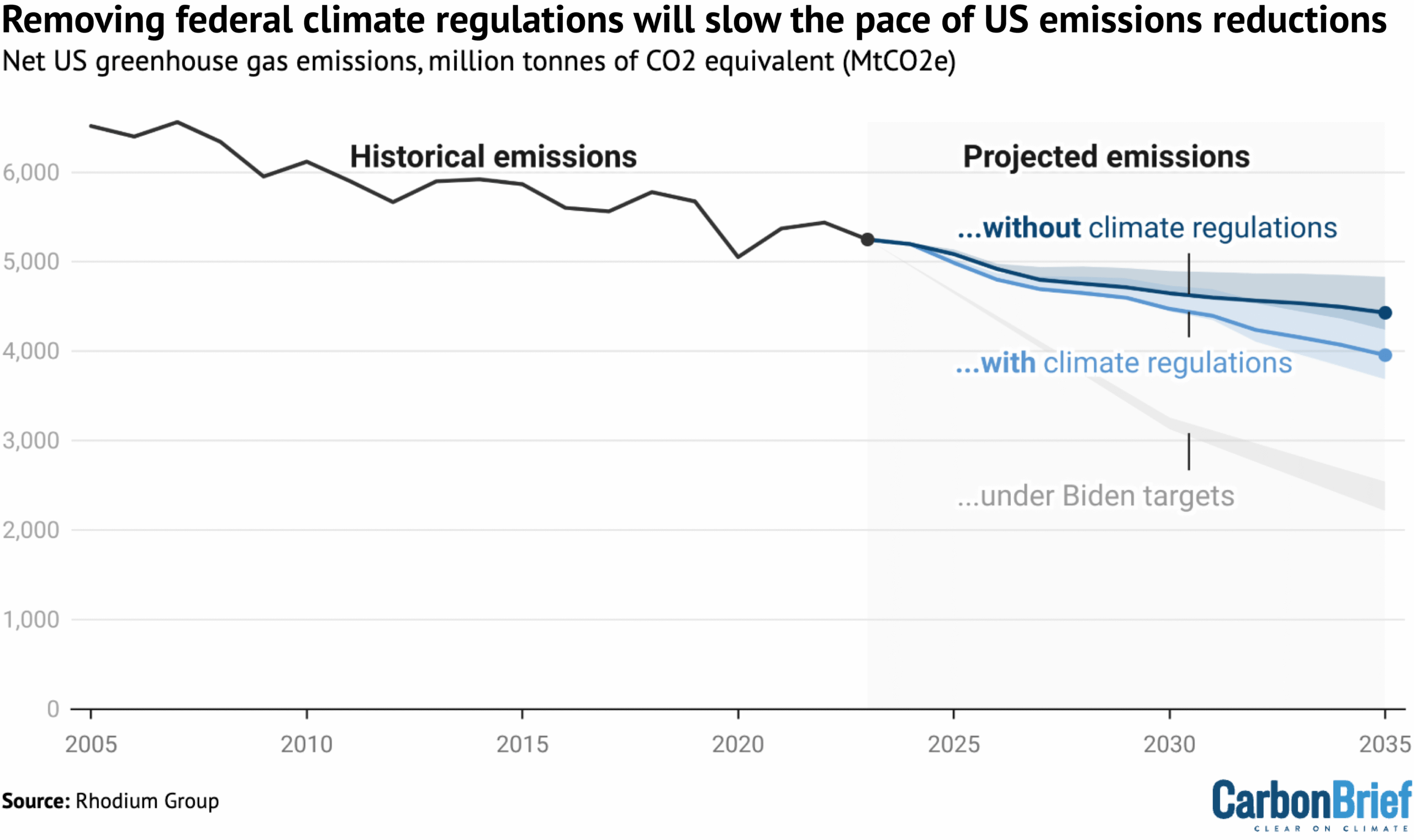

Repealing the US’s landmark “endangerment finding”, along with actions that rely on that finding, will slow the pace of US emissions cuts, according to Rhodium Group visualised by Carbon Brief. US president Donald Trump last week formally repealed the scientific finding that underpins federal regulations on greenhouse gas emissions, although the move is likely to face legal challenges. Data from the Rhodium Group, an independent research firm, shows that US emissions will drop more slowly without climate regulations. However, even with climate regulations, emissions are expected to drop much slower under Trump than under the previous Joe Biden administration, according to the analysis.

Spotlight

How a ‘tree invasion’ helped to fuel South America’s fires

This week, Carbon Brief explores how the “invasion” of non-native tree species helped to fan the flames of forest fires in Argentina and Chile earlier this year.

Since early January, Chile and Argentina have faced large-scale and deadly wildfires, including in Patagonia, which spans both countries.

These fires have been described as “some of the most significant and damaging in the region”, according to a World Weather Attribution (WWA) analysis covered by Carbon Brief.

In both countries, the fires destroyed vast areas of native forests and grasslands, displacing thousands of people. In Chile, the fires resulted in 23 deaths.

Multiple drivers contributed to the spread of the fires, including extended periods of high temperatures, low rainfall and abundant dry vegetation.

The WWA analysis concluded that human-caused climate change made these weather conditions at least three times more likely.

According to the researchers, another contributing factor was the invasion of non-native trees in the regions where the fires occurred.

The risk of non-native forests

In Argentina, the wildfires began on 6 January and persisted until the first week of February. They hit the city of Puerto Patriada and the Los Alerces and Lago Puelo national parks, in the Chubut province, as well as nearby regions.

In these areas, more than 45,000 hectares of native forests – such as Patagonian alerce tree, myrtle, coigüe and ñire – along with scrubland and grasslands, were consumed by the flames, according to the WWA study.

In Chile, forest fires occurred from 17 to 19 January in the Biobío, Ñuble and Araucanía regions.

The fires destroyed more than 40,000 hectares of forest and more than 20,000 hectares of non-native forest plantations, including eucalyptus and Monterey pine.

Dr Javier Grosfeld, a researcher at Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in northern Patagonia, told Carbon Brief that these species, introduced to Patagonia for production purposes in the late 20th century, grow quickly and are highly flammable.

Because of this, their presence played a role in helping the fires to spread more quickly and grow larger.

However, that is no reason to “demonise” them, he stressed.

Forest management

For Grosfeld, the problem in northern Patagonia, Argentina, is a significant deficit in the management of forests and forest plantations.

This management should include pruning branches from their base and controlling the spread of non-native species, he added.

A similar situation is happening in Chile, where management of pine and eucalyptus plantations is not regulated. This means there are no “firebreaks” – gaps in vegetation – in place to prevent fire spread, Dr Gabriela Azócar, a researcher at the University of Chile’s Centre for Climate and Resilience Research (CR2), told Carbon Brief.

She noted that, although Mapuche Indigenous communities in central-south Chile are knowledgeable about native species and manage their forests, their insight and participation are not recognised in the country’s fire management and prevention policies.

Grosfeld stated:

“We are seeing the transformation of the Patagonian landscape from forest to scrubland in recent years. There is a lack of preventive forestry measures, as well as prevention and evacuation plans.”

Watch, read, listen

FUTURE FURNACE: A Guardian video explored the “unbearable experience of walking in a heatwave in the future”.

THE FUN SIDE: A Channel 4 News video covered a new wave of climate comedians who are using digital platforms such as TikTok to entertain and raise awareness.

ICE SECRETS: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast explored how scientists study ice cores to understand what the climate was like in ancient times and how to use them to inform climate projections.

Coming up

- 22-27 February: Ocean Sciences Meeting, Glasgow

- 24-26 February: Methane Mitigation Europe Summit 2026, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 25-27 February: World Sustainable Development Summit 2026, New Delhi, India

Pick of the jobs

- The Climate Reality Project, digital specialist | Salary: $60,000-$61,200. Location: Washington DC

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), science officer in the IPCC Working Group I Technical Support Unit | Salary: Unknown. Location: Gif-sur-Yvette, France

- Energy Transition Partnership, programme management intern | Salary: Unknown. Location: Bangkok, Thailand

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires appeared first on Carbon Brief.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits