Removing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere is widely expected to play a key role in meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement.

But this will only be effective for slowing climate change if the CO2 can be stored securely and indefinitely.

This requires “geological carbon storage”, where captured CO2 is injected deep underground, where it can stay trapped for thousands of years.

While the current deployment of CO2 removal (CDR) technologies around the world is small, almost all facilities aim to store captured CO2 in sedimentary basins.

However, in our study in Nature, we show that current policy approaches to using these formations on a larger scale could be suffering from a false sense of abundance.

We find that – once technical, social and environmental risks are considered – the world’s available reserves of geological carbon storage are significantly more limited than most estimates suggest.

Our research shows that, of nearly 12,000bn tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2) of theoretical carbon storage capacity, just 1,460GtCO2 is risk-free.

Significantly, we find that, if all available safe carbon storage capacity were used for CO2 removal, this would contribute to only a 0.7C reduction in global warming.

In short, geological carbon storage is not limitless – on the contrary, its practical potential is a rather scarce planetary resource.

From technical potential to prudent limits

When studies estimate where carbon could be stored for the long term, they typically start by looking at all sedimentary basins worldwide to find those that are mature and stable.

However, norms of international environmental law indicate that high standards of due diligence must be applied to prevent transboundary environmental harm. As scientists, we were therefore interested in understanding how much storage capacity would be available when looking through a precautionary lens.

Our study develops the first global estimate of safe and durable carbon storage that takes into account social, environmental and technical risks – in addition to the geological qualities of the basins.

Rather than taking raw geological capacity at face value, we screen the potential locations for a number of factors:

- Seismic hazards

- Groundwater contamination.

- Proximity to population centres.

- Biodiversity protections, such as environmentally protected areas and the Arctic and Antarctic circles.

- Engineering limitations, such as basin depths that are too shallow to store carbon indefinitely or too deep underground and locations too deep in the ocean.

- Political feasibility, such as maritime areas outside of national jurisdictions or disputed geographical areas.

The results of our assessment are stark. We find that, out of nearly 12,000GtCO2 of theoretical carbon storage capacity in sedimentary basins, just 1,460GtCO2 can be considered robust for climate planning purposes.

We refer to this as “prudent” storage capacity.

This is an order of magnitude less than commonly-cited figures.

In 2005, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) special report on carbon capture and storage estimated that there is a “technical potential of at least about 2,000GtCO2…of storage capacity in geological formations”.

Over the two decades since, estimates have ballooned to 10,000-40,000GtCO2, depending on the academic or industry source that is consulted.

What this means for warming limits

Our research finds that if all reserves of “prudent” storage were used solely for removing CO2 from the atmosphere, they would enable – at most – a 0.7C reduction in global temperatures.

This falls to as little as 0.4C if we conservatively take the lower end of the likely (>66%) range of how much warming or cooling we expect per tonne of CO2 emitted or removed, respectively.

For the first time, our new study provides an estimate for an upper limit for how much past warming could be reversed through geological storage.

However, under most low-carbon pathways available in the academic and technical literature and assessed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, this prudent geological storage limit would be used up before 2200 – and some by 2100.

In many cases, storage is not used to draw down atmospheric CO2, but to balance the continued production of greenhouse gas and carbon pollution from human activities.

And yet, without sharp near-term cuts in gross emissions, the likely overshoot of the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C warming limit could prove irreversible.

Equity and responsibility

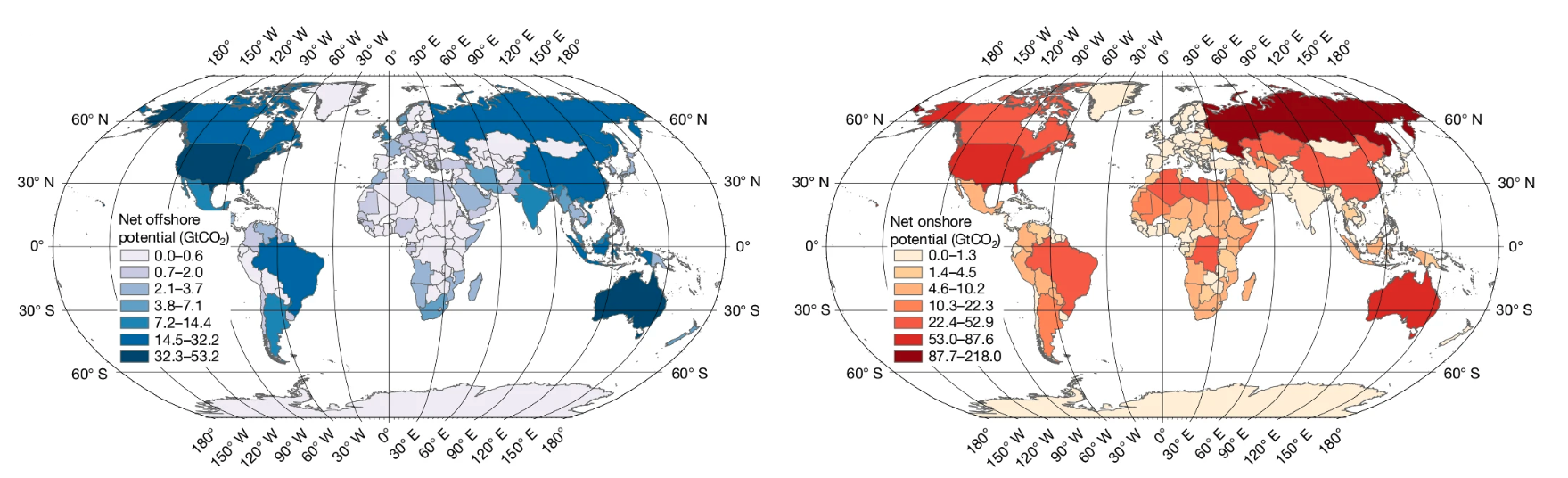

The maps below show how prudent storage capacity – for offshore (left) and onshore (right) basins – is not evenly distributed.

The “prudent” global storage potential (in GtCO2) for offshore (left) and onshore (right) basins, by individual countries. Darker shading indicates a greater amount of storage capacity. Source: Gidden et al. (2025)

Much of it is found in large, fossil-fuel-producing nations, such as the US, Australia, Russia and Saudi Arabia. These countries are among the world’s biggest historical emitters.

(This is not a coincidence, as these nations’ fossil-fuel-based economies are the result of relatively easily reachable geological deposits.)

However, the reality that the nations most responsible for emissions also appear best placed to store them raises equity concerns. Nations who benefitted from enabling carbon pollution would now also benefit from the clean up.

Other countries, such as Brazil and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, have substantial storage, but little domestic incentive to use it unless compensated.

Meanwhile, emissions-intensive nations would now be first in line to transform themselves from extractors to large-scale injectors of carbon – and could benefit from new business opportunities, often paid for by the public purse.

However, sovereign wealth funds – state-owned investment funds, often built on fossil revenues – could play a role in financing this shift, in line with the “polluter pays” principle.

Planning for scarcity

Treating storage as a finite and scarce resource has a knock-on effect for climate policy.

For example, governments would need to decide explicitly how they intend to allocate limited carbon storage capacity – should storage capacity be used to abate residual, industrial and fossil-fuel emissions, or for CO2 that has been directly pulled from the atmosphere?

Norms of international environmental law – and the recent “advisory opinion” on climate change from the International Court of Justice – provide guidance as to what countries ought to do. The principle of harm prevention indicates that risks of climate harm should be minimised where possible.

To limit risks to implementing climate targets, carbon capture and storage (CCS) should be seen as a complement to – but not a substitute – for rapid emissions cuts. This recommendation is not new – it has long been called for by researchers looking at the trade-offs and negative side-effects of specific negative emissions technologies, including the impacts poorly governed deployment of these technologies can have on biodiversity and food security.

Our geological storage estimate represents an assessment of reserves today – but this is likely to change with time as knowledge, preferences and governance of CO2 storage change.

CDR technologies that provide alternatives to geological storage, such as mineralisation in basalt, show promise. However, these technologies remain at pilot scale, with only a few million tonnes stored to date.

Climate strategies that rely on nascent CDR technologies would not constitute a strategy that minimises risks and potential harm to today’s and future generations.

The bottom line

Geological carbon storage is not a limitless backstop – and assuming otherwise puts the world at risk of irreversibly exceeding the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C threshold for global warming.

However, at the same time, carbon storage will almost certainly play a pivotal role in any future where global “net-zero” CO2 or greenhouse gas emissions is achieved.

By acknowledging the scarcity of carbon storage – and designating reserves for essential and strategic uses – governments can limit the risks of harm to people and the planet.

The post Guest post: How the role of carbon storage has been hugely overestimated appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: How the role of carbon storage has been hugely overestimated

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: The climate papers most featured in the media in 2025

The year 2025 saw the return to power of Donald Trump, a jewellery heist at the Louvre museum in Paris and an engagement that “broke the internet”.

Amid the biggest stories of the year, climate change research continued to feature prominently in news and social media feeds.

Using data from Altmetric, which scores research papers according to the attention they receive online, Carbon Brief has compiled its annual list of the 25 most talked-about climate-related studies of the past year.

The top 10 – shown in the infographic above and list below – include research into declining butterflies, heat-related deaths, sugar intake and the massive loss of ice from the world’s glaciers:

- Indicators of Global Climate Change 2024: annual update of key indicators of the state of the climate system and human influence

- Rapid butterfly declines across the US during the 21st century

- Global warming has accelerated: Are the UN and the public well informed?

- Community estimate of global glacier mass changes from 2000 to 2023

- The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable and just food systems

- Carbon majors and the scientific case for climate liability

- Estimating future heat-related and cold-related mortality under climate change, demographic and adaptation scenarios in 854 European cities

- Systematic attribution of heatwaves to the emissions of carbon majors

- Ambient outdoor heat and accelerated epigenetic aging among older adults in the US

- Rising temperatures increase added sugar intake disproportionately in disadvantaged groups in the US

Later in this article, Carbon Brief looks at the rest of the top 25 and provides analysis of the most featured journals, as well as the gender diversity and country of origin of authors.

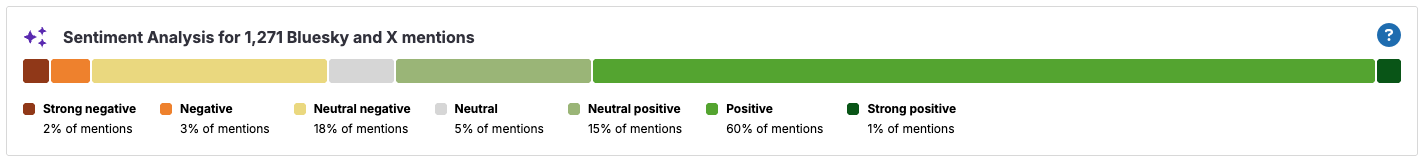

New for this year is the inclusion of Altmetric’s new “sentiment analysis”, which scores how positive or negative a paper’s social media attention has been.

(For Carbon Brief’s previous Altmetric articles, see the links for 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 and 2015.)

Global indicators

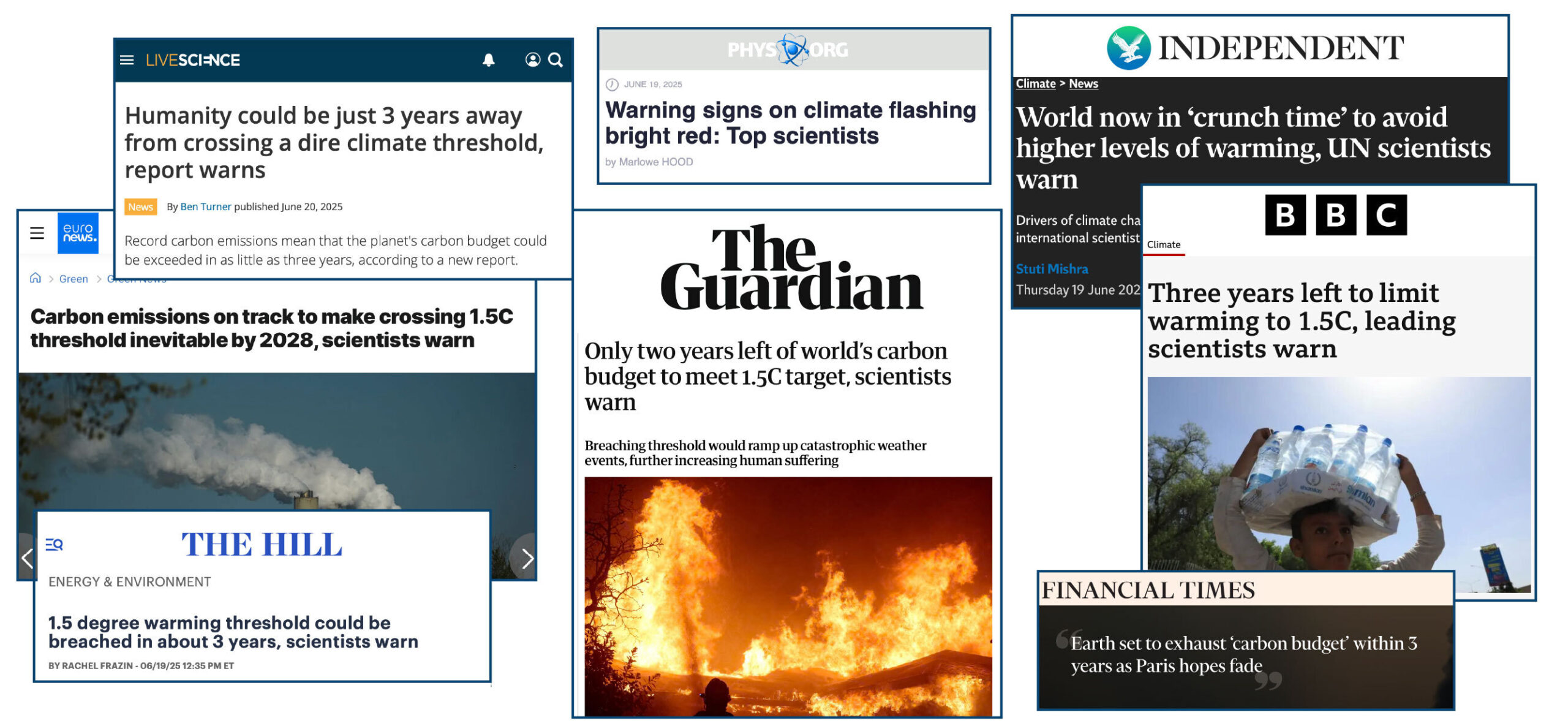

The top-scoring climate paper of 2025, ranking 24th of any research paper on any topic, is the annual update of the “Indicators of Global Climate Change” (IGCC) report.

The report was established in 2023 to help fill the gap in climate information between assessments of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which can take up to seven years to complete. It includes the latest data on global temperatures, the remaining carbon budget, greenhouse gas emissions and – for the first time – sea level rise.

The paper, published in Earth System Science Data, has an Altmetric score of 4,099. This makes it the lowest top-scoring climate paper in Carbon Brief’s list since 2017.

(An Altmetric score combines the mentions that published peer-reviewed research has received from online news articles, blogs, Wikipedia and on social media platforms such as Facebook, Reddit, Twitter and Bluesky. See an earlier Carbon Brief article for more on how Altmetric’s scoring system works.)

Previous editions of the IGCC have also appeared in Carbon Brief’s list – the 2024 and 2023 iterations ranked 17th and 18th, respectively.

This year’s paper was mentioned 556 times in online news stories, including in the Associated Press, Guardian, Independent, Hill and BBC News.

Many outlets led their coverage with the study’s findings on the global “carbon budget”. This warned that the remaining carbon budget to limit warming to 1.5C will be exhausted in just three years if global emissions continue at their current rate.

In a Carbon Brief guest post about the study, authors Prof Piers Forster and Dr Debbie Rosen from the University of Leeds wrote:

“It is also now inevitable that global temperatures will reach 1.5C of long-term warming in the next few years unless society takes drastic, transformative action…Every year of delay brings reaching 1.5C – or even higher temperatures – closer.”

Forster, who was awarded a CBE in the 2026 new year honours list, tells Carbon Brief that media coverage of the study was “great” at “putting recent extreme weather in the context of rapid long-term rates of global warming”.

However, he adds:

“Climate stories are not getting the coverage they deserve or need at the moment so the community needs to get all the help we can for getting clear consistent messages out there.”

The paper was tweeted more than 300 times and posted on Bluesky more than 950 times. It also appeared in 22 blogs.

Using AI, Altmetric now analyses the “sentiment” of this social media attention. As the summary figure below shows, the posts about this paper were largely positive, with an approximate 3:1 split of positive and negative attention.

Butterfly decline

With an Altmetric score of 3,828, the second-highest scoring climate paper warns of “widespread” declines in butterfly numbers across the US since the turn of the century.

The paper, titled “Rapid butterfly declines across the US during the 21st century” and published in Science, identifies a 22% fall in butterfly numbers across more than 500 species between 2000 and 2020.

(There is a higher-scoring paper, “The 2025 state of the climate report: a planet on the brink”, in the journal BioScience, but it is a “special report” and was not formally peer reviewed.)

The scale of the decline suggests “multiple and broadly acting threats, including habitat loss, climate change and pesticide use”, the paper says. The authors find that “species generally had stronger declines in more southerly parts of their ranges”, with some of the most negative trends in the driest and “most rapidly warming” US states.

The research was covered in 560 news articles, including the New York Times, Guardian, Associated Press, NPR, El País and BBC News. Much of the news coverage led with the 22% decline figure.

The paper was also mentioned in 13 blogs, more than 750 Bluesky posts and more than 600 tweets.

The sentiment analysis reveals that social media posts about the paper were largely negative. However, closer inspection reveals that this negativity is predominantly towards the findings of the paper, not the research itself.

For example, a Bluesky post on the “distressing” findings by one of the study’s authors is designated as “neutral negative” by Altmetric’s AI analysis.

In a response to a query from Carbon Brief, Altmetric explains that the “goal is to measure how people feel about the research paper itself, not the topic it discusses”. However, in some cases the line can be “blurred” as the AI “sometimes struggles to separate the subject matter from the critique”. The organisation adds that it is “continuously working on improving our models to better distinguish between the post’s content and the research output”.

On the attention that the paper received, lead author Dr Collin Edwards of Washington State University in Vancouver says that “first and foremost, people care about butterflies and our results are broad-reaching, unequivocal and, unfortunately, very concerning”.

Edwards tells Carbon Brief he hopes the clarity of the writing made the paper accessible to readers, noting that he and his co-authors “sweat[ed] over every word”.

The resulting news coverage “accurately captured the science”, Edwards says:

“Much as I wish our results were less consistently grim, the consistency and simplicity of our findings mean that even if a news story only provides the highest level summary, it isn’t misleading readers by skipping some key caveat or nuance that changes the interpretation.”

Warming ‘acceleration’

In third place in Carbon Brief’s list for 2025 is the latest scientific paper from veteran climatologist Dr James Hansen, former director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and now adjunct professor at Columbia University’s Earth Institute.

The paper, titled “Global warming has accelerated: Are the UN and the public well-informed?” was published in the journal Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. It generated an Altmetric score of 3,474.

The study estimates that the record-high global temperatures in the last few years were caused by a combination of El Niño and a reduction in air pollution from international shipping.

The findings suggest that the cooling effect of aerosols – tiny, light‑scattering particles produced mainly by burning fossil fuels – has masked more of the warming driven by greenhouse gases than previously estimated by the IPCC.

As efforts to tackle air pollution continue to reduce aerosol emissions, warming will accelerate further – reaching 2C by 2045, according to the research.

The paper was covered by almost 400 news stories – driven, in part, by Hansen’s comments in a press briefing that the Paris Agreement’s 2C warming limit was already “dead”.

Hansen’s analysis received a sceptical response from some scientists. For example, Dr Valerie Masson-Delmotte, an IPCC co-chair for its most recent assessment report on climate science, told Agence France-Presse the research “is not published in a climate science journal and it formulates a certain number of hypotheses that are not consistent with all the available observations”.

In addition, other estimates, including by Carbon Brief, suggest new shipping regulations have made a smaller contribution to warming than estimated by Hansen.

Hansen tells Carbon Brief that the paper “did ok” in terms of media coverage, although notes “it’s on [scientists] to do a better job of making clear what the core issues are in the physics of climate change”.

With more than 1,000 tweets, the paper scored highest in the top 25 for posts on Twitter. It was also mentioned in more than 800 Bluesky posts and on 27 blogs.

The sentiment analysis suggests that these posts were largely positive, with just a small percentage of negative comments.

Making the top 10

Ranking fourth in Carbon Brief’s analysis is a Nature paper calculating changes in global glacier mass over 2000-23. The study finds glaciers worldwide lost 273bn tonnes of ice annually over that time – with losses increasing by 36% between 2000-11 and 2012-23.

The study has an Altmetric score of 3,199. It received more news coverage than any other paper in this year’s top 25, amassing 1,187 mentions. with outlets including the Guardian, Associated Press and Economic Times.

At number five, with an Altmetric score of 2,860, is the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable and just food systems.

Carbon Brief’s coverage of the report highlights that “a global shift towards ‘healthier’ diets could cut non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions, such as methane, from agriculture by 15% by 2050”. It adds:

“The findings build on the widely cited 2019 report from the EAT-Lancet Commission – a group of leading experts in nutrition, climate, economics, health, social sciences and agriculture from around the world.”

Also making the top 10 – ranking sixth and eighth – are a pair of papers published in Nature, which both link extreme heat to the emissions of specific “carbon majors” – large producers of fossil fuels, such as ExxonMobil, Shell and Saudi Aramco,.

The first is a perspective, titled “Carbon majors and the scientific case for climate liability”, published in April. It begins:

“Will it ever be possible to sue anyone for damaging the climate? Twenty years after this question was first posed, we argue that the scientific case for climate liability is closed. Here we detail the scientific and legal implications of an ‘end-to-end’ attribution that links fossil fuel producers to specific damages from warming.”

The authors find “trillions (of US$) in economic losses attributable to the extreme heat caused by emissions from individual companies”.

The paper was mentioned 1,329 times on Bluesky – the highest in this year’s top 25. It was also mentioned in around 270 news stories.

Published four months later, the second paper uses extreme event attribution to assess the impact of climate change on more than 200 heatwaves recorded since the year 2000.

The authors find one-quarter of the heatwaves would have been “virtually impossible” without human-caused global warming. They add that the heatwaves were, on average, 1.7C hotter due to climate change, with half of this increase due to emissions stemming from the operations and production of carbon majors.

This study was mentioned in almost 300 news stories – including by Carbon Brief – as well as 222 tweets and 823 posts on Bluesky.

In seventh place is a Nature Medicine study, which quantifies how heat-related and cold-related deaths will change over the coming century as the climate warms.

A related research briefing explains the main findings of the paper:

“Heat-related deaths are estimated to increase more rapidly than cold-related deaths are estimated to decrease under future climate change scenarios across European cities. An unrealistic degree of adaptation to heat would be required to revert this trend, indicating the need for strong policies to reduce greenhouse gases emissions.”

The paper was mentioned 345 times in the news, including in the Financial Times, New Scientist, Guardian and Bloomberg.

The paper in ninth place also analyses the health impacts of extreme heat. The study, published in Science Advances, finds that extreme heat can speed up biological ageing in older people.

Rounding out the top 10 is a Nature Climate Change study, titled “Rising temperatures increase added sugar intake disproportionately in disadvantaged groups in the US”.

The study finds that at higher temperatures, people in the US consume more sugar – mainly due to “higher consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and frozen desserts”. The authors project that warming of 5C would drive additional sugar consumption of around 3 grams per day, “with vulnerable groups at an even higher risk”.

Elsewhere in the top 25

The rest of the top 25 includes a wide range of research, from “glacier extinction” and wildfires to Amazon drought and penguin guano.

In 13th place is a Nature Climate Change study that finds the wealthiest 10% of people – defined as those who earn at least €42,980 (£36,605) per year – contributed seven times more to the rise in monthly heat extremes around the world than the global average.

The authors also explore country-level emissions, finding that the wealthiest 10% in the US produced the emissions that caused a doubling in heat extremes across “vulnerable regions” globally.

(See Carbon Brief’s coverage of the paper for more details.)

In 15th place is the annual Lancet Countdown on health and climate change – a lengthy report with more than 120 authors.

The study warns that “climate change is increasingly destabilising the planetary systems and environmental conditions on which human life depends”.

This annual analysis from the Lancet often features in Carbon Brief’s top 25 analysis. After three years in the Carbon Brief’s top 10 over 2020-23, the report landed in 20th place in 2023 and missed out on a spot in the top 25 altogether in 2024.

In 16th place is a Science Advances study, titled “Increasing rat numbers in cities are linked to climate warming, urbanisation and human population”. The study uses public complaint and inspection data from 16 cities around the world to estimate changes in rat populations.

It finds that “warming temperatures and more people living in cities may be expanding the seasonal activity periods and food availability for urban rats”.

The study received 320 new mentions, including in the Washington Post, New Scientist and National Geographic.

In 21st place is a Nature Climate Change paper, titled “Peak glacier extinction in the mid-21st century”. The study authors “project a sharp rise in the number of glaciers disappearing worldwide, peaking between 2041 and 2055 with up to ~4,000 glaciers vanishing annually”.

Completing the top 25 is a Nature study on the “prudent planetary limit for geological carbon storage” – where captured CO2 is injected deep underground, where it can stay trapped for thousands of years.

In a Carbon Brief guest post, study authors Dr Matthew Gidden and Prof Joeri Rogelj explain that carbon dioxide removal will only be effective at limiting global temperature rise if captured CO2 is injected “deep underground, where it can stay trapped for thousands of years”.

The guest post warns that “geological carbon storage is not limitless”. It states that “if all available safe carbon storage capacity were used for CO2 removal, this would contribute to only a 0.7C reduction in global warming”.

Top journals

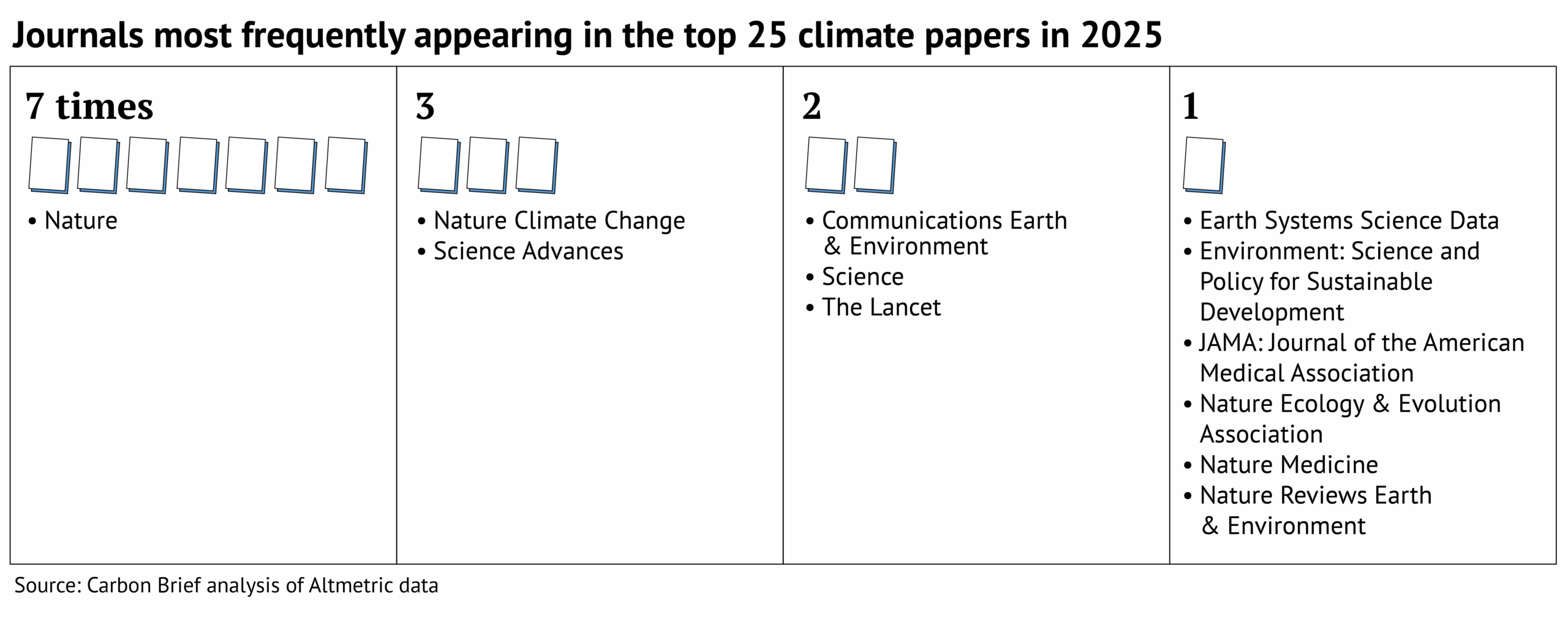

The journal Nature dominates Carbon Brief’s top 25, with seven papers featured.

Many other journals in the Springer Nature stable also feature, including Nature Climate Change (three), Communications Earth & Environment (two), as well as Nature Ecology & Evolution, Nature Medicine and Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (one each).

Also appearing more than once in the top 25 are Science Advances (three), Science (two) and the Lancet (two).

This is shown in the graphic below.

All the final scores for 2025 can be found in this spreadsheet.

Diversity in the top 25

The top 25 climate papers of 2025 cover a huge range of topics and scope. However, analysis of their authors reveals a distinct lack of diversity.

In total, the top 25 includes more than 650 authors – the highest number since Carbon Brief began this analysis in 2022.

This is largely due to a few publications with an exceptionally high number of authors. For example, the 2025 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change has almost 130 authors alone, accounting for almost one-fifth of authors in this analysis.

Carbon Brief recorded the gender and country of affiliation for each of these authors. (The methodology used was developed by Carbon Brief for analysis presented in a special 2021 series on climate justice.)

The analysis reveals that 88% of the authors of the climate papers most featured in the media in 2025 are from institutions in the global north.

Carbon Brief defines the global north as North America, Europe, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. It defines the global south as Asia (excluding Japan), Africa, Oceania (excluding Australia and New Zealand), Latin America and the Caribbean.

The analysis shows that 53% of authors are from European institutions, while only 1% of authors are from institutions in Africa.

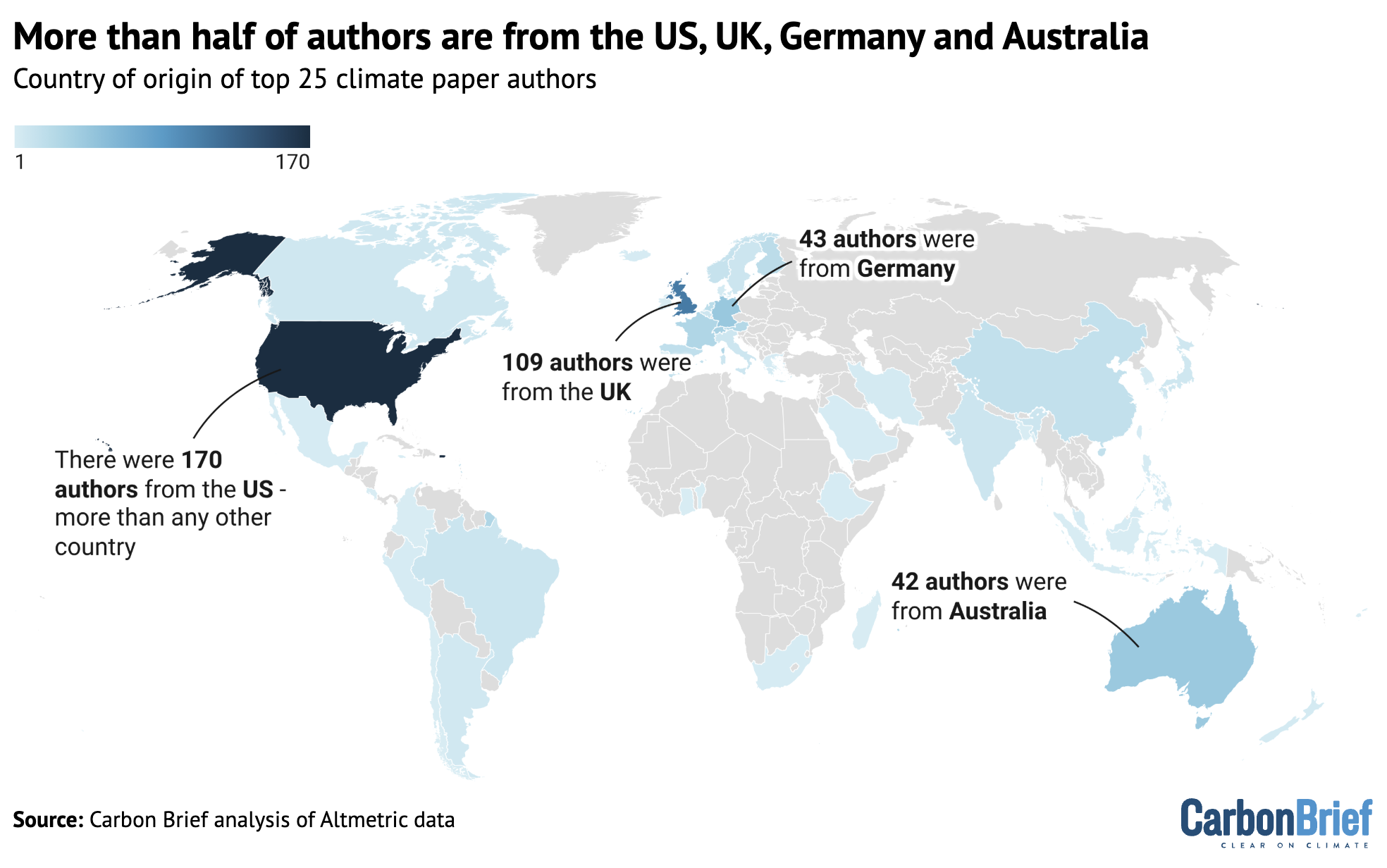

Further data analysis shows that there are also inequalities within continents. The map below shows the percentage of authors from each country, where dark blue indicates a higher percentage. Countries that are not represented by any authors in the analysis are shown in grey.

The top-ranking countries on this map are the US and the UK, which account for 26% and 16% of the authors, respectively.

Carbon Brief also analysed the gender of the authors.

Only one-third of authors from the top 25 climate papers of 2025 are women and only five of the 25 papers list a woman as lead author.

The plot below shows the number of authors from each continent, separated into men (dark blue) and women (light blue).

The full spreadsheet showing the results of this data analysis can be found here. For more on the biases in climate publishing, see Carbon Brief’s article on the lack of diversity in climate-science research.

The post Analysis: The climate papers most featured in the media in 2025 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: The climate papers most featured in the media in 2025

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Coal power drops in China and India for first time in 52 years after clean-energy records

Coal power generation fell in both China and India in 2025, the first simultaneous drop in half a century, after each nation added record amounts of clean energy.

The new analysis for Carbon Brief shows that electricity generation from coal in India fell by 3.0% year-on-year (57 terawatt hours, TWh) and in China by 1.6% (58TWh).

The last time both countries registered a drop in coal power output was in 1973.

The fall in 2025 is a sign of things to come, as both countries added a record amount of new clean-power generation last year, which was more than sufficient to meet rising demand.

Both countries now have the preconditions in place for peaking coal-fired power, if China is able to sustain clean-energy growth and India meets its renewable energy targets.

These shifts have international implications, as the power sectors of these two countries drove 93% of the rise in global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from 2015-2024.

While many challenges remain, the decline in their coal-power output marks a historic moment, which could help lead to a peak in global emissions.

Double drop

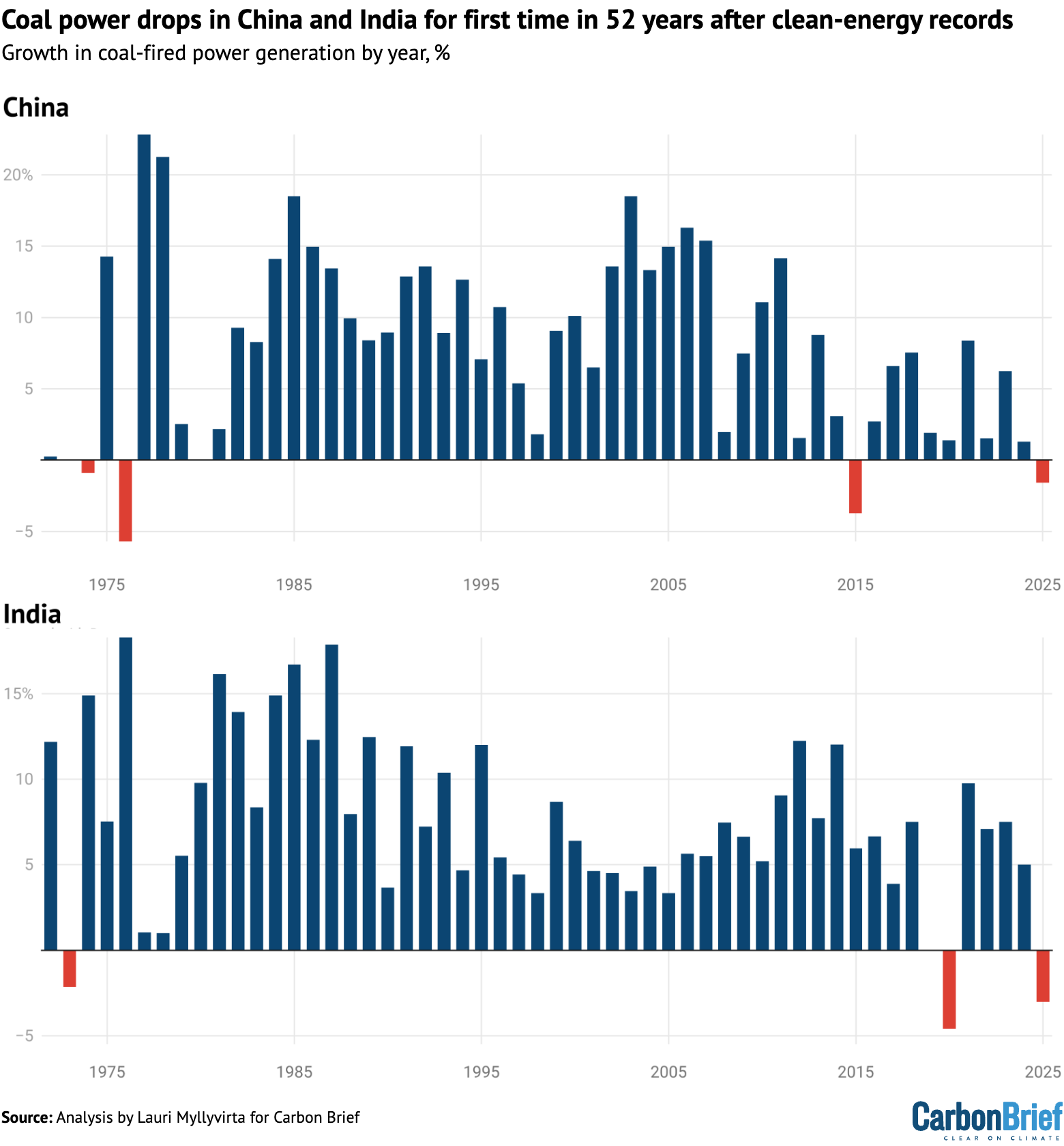

The new analysis shows that power generation from coal fell by 1.6% in China and by 3.0% in India in 2025, as non-fossil energy sources grew quickly enough in both countries to cover electricity consumption growth. This is illustrated in the figure below.

Growth in coal-fired power generation in China and India by year, %, 1972-2025. Source: Analysis by Lauri Myllyvirta for Carbon Brief. Further details below.

China achieved this feat even as electricity demand growth remained rapid at 5% year-on-year. In India, the drop in coal was due to record clean-energy growth combined with slower demand growth, resulting from mild weather and a longer-term slowdown.

The simultaneous drop for coal power in both countries in 2025 is the first since 1973, when much of the world was rocked by the oil crisis. Both China and India saw weak power demand growth that year, combined with increases in power generation from other sources – hydro and nuclear in the case of India and oil in the case of China.

China’s recent clean-energy generation growth, if sustained, is already sufficient to secure a peak in coal power. Similarly, India’s clean-energy targets, if they are met, will enable a peak in coal before 2030, even if electricity demand growth accelerates again.

In 2025, China will likely have added more than 300 gigawatts (GW) of solar and 100GW of wind power, both clear new records for China and, therefore, for any country ever.

Power generation from solar and wind increased by 450TWh in the first 11 months of the year and nuclear power delivering another 35TWh. This put the growth of non-fossil power generation, excluding hydropower, squarely above the 460TWh increase in demand.

Growth in clean-power generation has kept ahead of demand growth and, as a result, power-sector coal use and CO2 emissions have been falling since early 2024.

Coal use outside the power sector is falling, too, mostly driven by falling output of steel, cement and other construction materials, the largest coal-consuming sectors after power.

In India’s case, the fall in coal-fired power in 2025 was a result of accelerated clean-energy growth, a longer-term slowdown in power demand growth and milder weather, which resulted in a reduction in power demand for air conditioning.

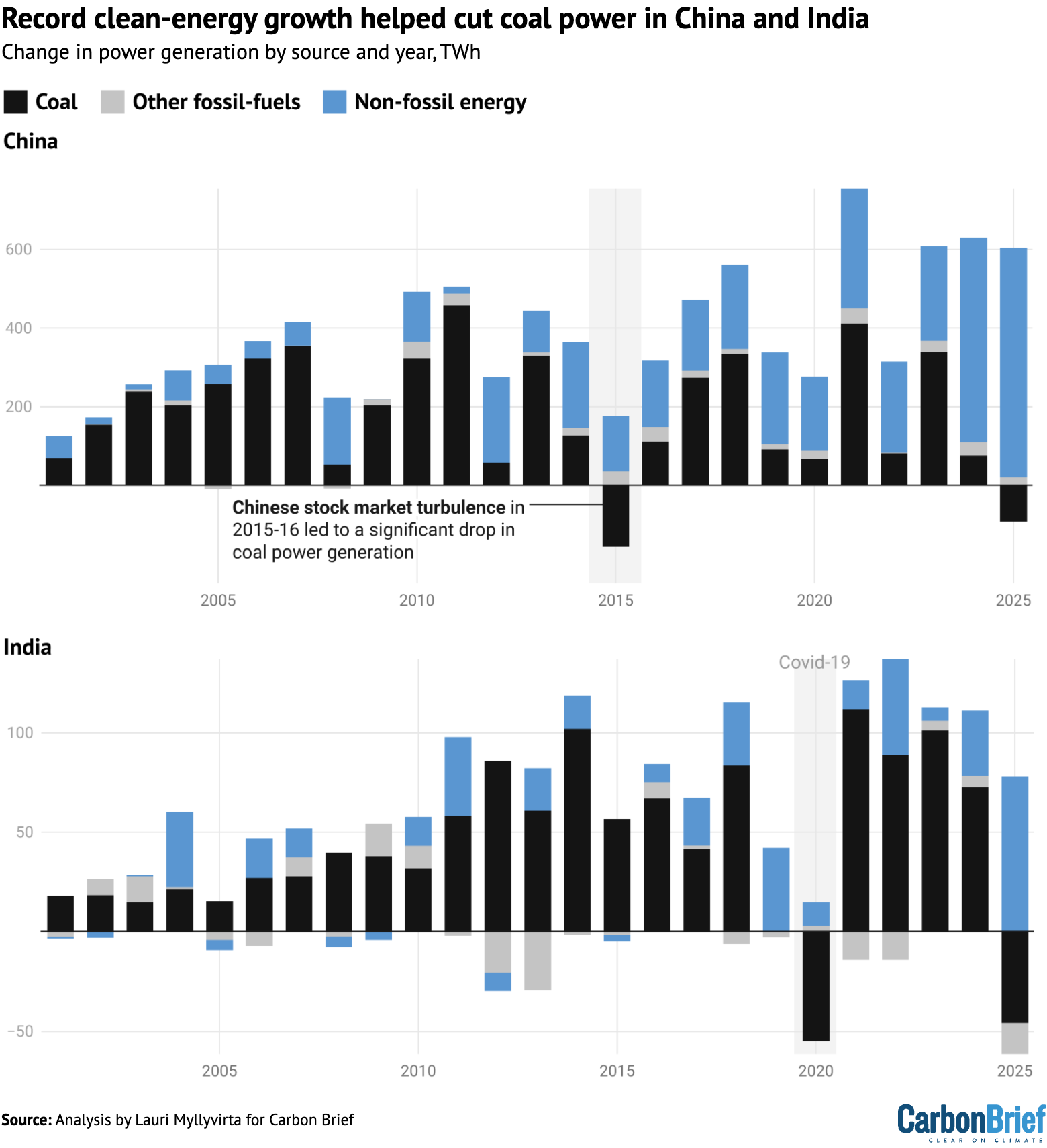

Faster clean-energy growth contributed 44% of the reduction in coal and gas, compared to the trend in 2019-24, while 36% was contributed by milder weather and 20% by slower underlying demand growth. This is the first time that clean-energy growth has played a significant role in driving down India’s coal-fired power generation, as shown below.

Change in power generation in China and India by source and year, terawatt hours 2000-2025. Source: Analysis by Lauri Myllyvirta for Carbon Brief. Further details below.

India added 35GW of solar, 6GW wind and 3.5GW hydropower in the first 11 months of 2025, with renewable energy capacity additions picking up 44% year-on-year.

Power generation from non-fossil sources grew 71TWh, led by solar at 33TWh, while total generation increased 21TWh, similarly pushing down power generation from coal and gas.

The increase in clean power is, however, below the average demand growth recorded from 2019 to 2024, at 85TWh per year, as well as below the projection for 2026-30.

This means that clean-energy growth would need to accelerate in order for coal power to see a structural peak and decline in output, rather than a short-term blip.

Meeting the government’s target for 500GW of non-fossil power capacity by 2030, set by India’s prime minister Narendra Modi in 2021, requires just such an acceleration.

Historic moment

While the accelerated clean-energy growth in China and India has upended the outlook for their coal use, locking in declines would depend on meeting a series of challenges.

First, the power grids would need to be operated much more flexibly to accommodate increasing renewable shares. This would mean updating old power market structures – built to serve coal-fired power plants – both in China and India.

Second, both countries have continued to add new coal-fired power capacity. In the short term, this is leading to a fall in capacity utilisation – the number of hours each coal unit is able to operate – as power generation from coal falls.

(Both China and India have been adding new coal-power capacity in response to increases in peak electricity demand. This includes rising demand for air conditioning, in part resulting from extreme heat driven by the historical emissions that have caused climate change.)

If under-construction and permitted coal-power projects are completed, they would increase coal-power capacity by 28% in China and 23% in India. Without marked growth in power generation from coal, the utilisation of this capacity would fall significantly, causing financial distress for generators and adding costs for power users.

In the longer term, new coal-power capacity additions would have to be slowed down substantially and retirements accelerated, to make space for further expansion of clean energy in the power system.

Despite these challenges ahead, the drop in coal power and record increase in clean energy in China and India marks a historic moment.

Power generation in these two countries drove more than 90% of the increase in global CO2 emissions from all sources between 2015-2024 – with 78% from China and 16% from India – making their power sectors the key to peaking global emissions.

About the data

China’s coal-fired power generation until November 2025 is calculated from monthly data on the capacity and utilisation of coal-fired power plants from China Electricity Council (CEC), accessed through Wind Financial Terminal.

For December, year-on-year growth is based on a weekly survey of power generation at China’s coal plants by CEC, with data up to 25 December. This data closely predicts CEC numbers for the full month.

Other power generation and capacity data is derived from CEC and National Bureau of Statistics data, following the methodology of CREA’s monthly snapshot of energy and emissions trends in China.

For India, the analysis uses daily power generation data and monthly capacity data from the Central Electricity Authority, accessed through a dashboard published by government thinktank Niti Aayog.

The role of coal-fired power in China and India in driving global CO2 emissions is calculated from the International Energy Agency (IEA) World Energy Balances until 2023, applying default CO2 emission factors from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

To extend the calculation to 2024, the year-on-year growth of coal-fired power generation in China and India is taken from the sources above, and the growth of global fossil-fuel CO2 emissions was taken from the Energy Institute’s Statistical Review of World Energy.

The time series of coal-fired power generation since 1971, used to establish the fact that the previous time there was a drop in both countries was 1973, was taken from the IEA World Energy Balances. This dataset uses fiscal years ending in March for India. Calendar-year data was available starting from 2000 from Ember’s yearly electricity data.

The post Analysis: Coal power drops in China and India for first time in 52 years after clean-energy records appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Coal power drops in China and India for first time in 52 years after clean-energy records

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 9 January 2026: US to exit global climate treaty; Venezuelan oil ‘uncertainty’; ‘Hardest truth’ for Africa’s energy transition

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

US to pull out from UNFCC, IPCC

CLIMATE RETREAT: The Trump administration announced its intention to withdraw the US from the world’s climate treaty, CNN reported. The move to leave the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in addition to 65 other international organisations, was announced via a White House memorandum that states these bodies “no longer serve American interests”, the outlet added. The New York Times explained that the UNFCCC “counts all of the other nations of the world as members” and described the move as cementing “US isolation from the rest of the world when it comes to fighting climate change”.

MAJOR IMPACT: The Associated Press listed all the organisations that the US is exiting, including other climate-related bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). The exit also means the withdrawal of US funding from these bodies, noted the Washington Post. Bloomberg said these climate actions are likely to “significantly limit the global influence of those entities”. Carbon Brief has just published an in-depth Q&A on what Trump’s move means for global climate action.

Oil prices fall after Venezuela operation

UNCERTAIN GLUT: Global oil prices fell slightly this week “after the US operation to seize Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro created uncertainty over the future of the world’s largest crude reserves”, reported the Financial Times. The South American country produces less than 1% of global oil output, but it holds about 17% of the world’s proven crude reserves, giving it the potential to significantly increase global supply, the publication added.

TRUMP DEMANDS: Meanwhile, Trump said Venezuela “will be turning over” 30-50m barrels of oil to the US, which will be worth around $2.8bn (£2.1bn), reported BBC News. The broadcaster added that Trump claims this oil will be sold at market price and used to “benefit the people of Venezuela and the US”. The announcement “came with few details”, but “marked a significant step up for the US government as it seeks to extend its economic influence in Venezuela and beyond”, said Bloomberg.

Around the world

- MONSOON RAIN: At least 16 people have been killed in flash floods “triggered by torrential rain” in Indonesia, reported the Associated Press.

- BUSHFIRES: Much of Australia is engulfed in an extreme heatwave, said the Guardian. In Victoria, three people are missing amid “out of control” bushfires, reported Reuters.

- TAXING EMISSIONS: The EU’s landmark carbon border levy, known as “CBAM”, came into force on 1 January, despite “fierce opposition” from trading partners and European industry, according to the Financial Times.

- GREEN CONSUMPTION: China’s Ministry of Commerce and eight other government departments released an action plan to accelerate the country’s “green transition of consumption and support high-quality development”, reported Xinhua.

- ACTIVIST ARRESTED: Prominent Indian climate activist Harjeet Singh was arrested following a raid on his home, reported Newslaundry. Federal forces have accused Singh of “misusing foreign funds to influence government policies”, a suggestion that Singh rejected as “baseless, biased and misleading”, said the outlet.

- YOUR FEEDBACK: Please let us know what you thought of Carbon Brief’s coverage last year by completing our annual reader survey. Ten respondents will be chosen at random to receive a CB laptop sticker.

47%

The share of the UK’s electricity supplied by renewables in 2025, more than any other source, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Latest climate research

- Deforestation due to the mining of “energy transition minerals” is a “major, but overlooked source of emissions in global energy transition” | Nature Climate Change

- Up to three million people living in the Sudd wetland region of South Sudan are currently at risk of being exposed to flooding | Journal of Flood Risk Management

- In China, the emissions intensity of goods purchased online has dropped by one-third since 2000, while the emissions intensity of goods purchased in stores has tripled over that time | One Earth

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

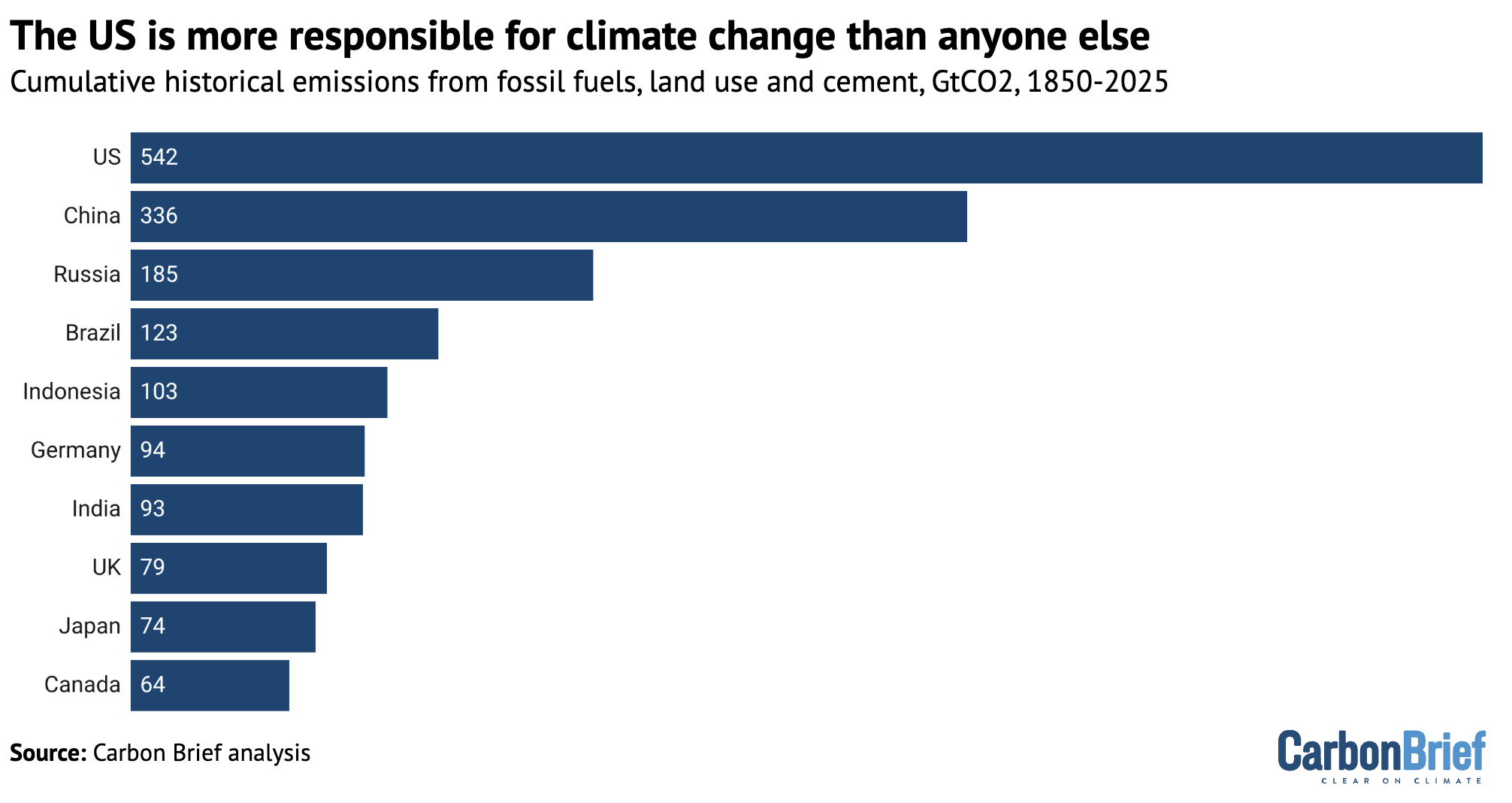

The US, which has announced plans to withdraw from the UNFCCC, is more responsible for climate change than any other country or group in history, according to Carbon Brief analysis. The chart above shows the cumulative historical emissions of countries since the advent of the industrial era in 1850.

Spotlight

How to think about Africa’s just energy transition

African nations are striving to boost their energy security, while also addressing climate change concerns such as flood risks and extreme heat.

This week, Carbon Brief speaks to the deputy Africa director of the Natural Resource Governance Institute, Ibrahima Aidara, on what a just energy transition means for the continent.

Carbon Brief: When African leaders talk about a “just energy transition”, what are they getting right? And what are they still avoiding?

Ibrahima Aidara: African leaders are right to insist that development and climate action must go together. Unlike high-income countries, Africa’s emissions are extremely low – less than 4% of global CO2 emissions – despite housing nearly 18% of the world’s population. Leaders are rightly emphasising universal energy access, industrialisation and job creation as non-negotiable elements of a just transition.

They are also correct to push back against a narrow narrative that treats Africa only as a supplier of raw materials for the global green economy. Initiatives such as the African Union’s Green Minerals Strategy show a growing recognition that value addition, regional integration and industrial policy must sit at the heart of the transition.

However, there are still important blind spots. First, the distributional impacts within countries are often avoided. Communities living near mines, power infrastructure or fossil-fuel assets frequently bear environmental and social costs without sharing in the benefits. For example, cobalt-producing communities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or lithium-affected communities in Zimbabwe and Ghana, still face displacement, inadequate compensation, pollution and weak consultation.

Second, governance gaps are sometimes downplayed. A just transition requires strong institutions (policies and regulatory), transparency and accountability. Without these, climate finance, mineral booms or energy investments risk reinforcing corruption and inequality.

Finally, leaders often avoid addressing the issue of who pays for the transition. Domestic budgets are already stretched, yet international climate finance – especially for adaptation, energy access and mineral governance – remains far below commitments. Justice cannot be achieved if African countries are asked to self-finance a global public good.

CB: Do African countries still have a legitimate case for developing new oil and gas projects, or has the energy transition fundamentally changed what ‘development’ looks like?

IA: The energy transition has fundamentally changed what development looks like and, with it, how African countries should approach oil and gas. On the one hand, more than 600 million Africans lack access to electricity and clean cooking remains out of reach for nearly one billion people. In countries such as Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal and Tanzania, gas has been framed to expand power generation, reduce reliance on biomass and support industrial growth. For some contexts, limited and well-governed gas development can play a transitional role, particularly for domestic use.

On the other hand, the energy transition has dramatically altered the risks. Global demand uncertainty means new oil and gas projects risk becoming stranded assets. Financing is shrinking, with many development banks and private lenders exiting fossil fuels. Also, opportunity costs are rising; every dollar locked into long-lived fossil infrastructure is a dollar not invested in renewables, grids, storage or clean industry.

Crucially, development today is no longer just about exporting fuels. It is about building resilient, diversified economies. Countries such as Morocco and Kenya show that renewable energy, green industry and regional power trade can support growth without deepening fossil dependence.

So, the question is no longer whether African countries can develop new oil and gas projects, but whether doing so supports long-term development, domestic energy access and fiscal stability in a transitioning world – or whether it risks locking countries into an extractive model that benefits few and exposes countries to future shocks.

CB: What is the hardest truth about Africa’s energy transition that policymakers and international partners are still unwilling to confront?

IA: For me, the hardest truth is this: Africa cannot deliver a just energy transition on unfair global terms. Despite all the rhetoric, global rules still limit Africa’s policy space. Trade and investment agreements restrict local content, industrial policy and value-addition strategies. Climate finance remains fragmented and insufficient. And mineral supply chains are governed largely by consumer-country priorities, not producer-country development needs.

Another uncomfortable truth is that not every “green” investment is automatically just. Without strong safeguards, renewable energy projects and mineral extraction can repeat the same harms as fossil fuels: displacement, exclusion and environmental damage.

Finally, there is a reluctance to admit that speed alone is not success. A rushed transition that ignores governance, equity and institutions will fail politically and socially, and, ultimately, undermine climate goals.

If Africa’s transition is to succeed, international partners must accept African leadership, African priorities and African definitions of development, even when that challenges existing power dynamics in global energy and mineral markets.

Watch, read, listen

CRISIS INFLAMED: In the Brazilian newspaper Folha de São Paulo, columnist Marcelo Leite looked into the climate impact of extracting more oil from Venezuela.

BEYOND TALK: Two Harvard scholars argued in Climate Home News for COP presidencies to focus less on climate policy and more on global politics.

EU LEVIES: A video explainer from the Hindu unpacked what the EU’s carbon border tax means for India and global trade.

Coming up

- 10-12 January: 16th session of the IRENA Assembly, Abu Dhabi

- 13-15 January: Energy Security and Green Infrastructure Week, London

- 13-15 January: The World Future Energy Summit, Abu Dhabi

- 15 January: Uganda general elections

Pick of the jobs

- WRI Polsky Energy Center, global director | Salary: around £185,000. Location: Washington DC; the Hague, Netherlands; New Delhi, Mumbai, or Bengaluru, India; or London

- UK government Advanced Research and Invention Agency, strategic communications director – future proofing our climate and weather | Salary: £115,000. Location: London

- The Wildlife Trusts, head of climate and international policy | Salary: £50,000. Location: London

- Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, senior manager for climate | Salary: Unknown. Location: London, UK

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 9 January 2026: US to exit global climate treaty; Venezuelan oil ‘uncertainty’; ‘Hardest truth’ for Africa’s energy transition appeared first on Carbon Brief.

-

Greenhouse Gases5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits