Heat pumps are an alternative to gas boilers and wood stoves for indoor heating.

They now feature in most proposals for cutting greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero by mid-century in order to meet the globally agreed aim of avoiding dangerous climate change.

For example, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) says with high confidence that net-zero energy systems will include the electrification of heating “rely[ing] substantially on heat pumps” – with a possible exception only for extreme climates.

Heat pumps significantly cut greenhouse gas emissions from building heat and are the “central technology in the global transition to secure and sustainable heating”, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Heat pumps are also a mature technology and are very popular in countries such as Norway, Sweden and Finland, where they are the dominant heating technology. For the first time in 2022, heat pumps outsold gas boilers in the US – and they continued to do so in 2023.

Yet, in major economies such as the UK and Germany, heat pumps are the subject of hostile and misleading reporting across many mainstream media outlets.

Here, Carbon Brief factchecks 18 of the most common and persistent myths about heat pumps.

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps don’t work in existing buildings.’

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps only work in highly insulated buildings.’

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps only work with underfloor heating.’

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps won’t work in flats.’

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps don’t work when it’s cold.’

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps will always need a backup heating system to keep you warm.‘

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps won’t keep you warm.’

- INCOMPLETE: ‘You will freeze during a power cut and be better off with a gas boiler.’

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps are noisy.’

- INCOMPLETE: ‘Heat pumps cost more to run and will increase heating bills.’

- FALSE. ‘Turning gas to electricity to heat via a heat pump is less efficient than burning gas in a boiler.’

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps will never offset the carbon emissions resulting from making them.’

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps devalue properties.’

- INCOMPLETE: ‘Heat pumps are unaffordable.’

- INCOMPLETE: ‘The grid cannot cope with heat pumps.’

- INCOMPLETE: ‘Heat pumps don’t work with microbore piping.’

- FALSE: ‘Heat pumps don’t last long.’

- INCOMPLETE: ‘Heat pumps are new and untested technology.’

1. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps don’t work in existing buildings.’

In a recent survey in the UK, 20% of respondents said they believed that heat pumps only work in newer homes. In 2023, the Daily Telegraph even published an article with the headline: “Heat pumps won’t work in old homes, warns Bosch.”

In reality, millions of buildings of all ages have been fitted with heat pumps around the world. In fact, the UK government’s boiler upgrade scheme, which offers grants to households replacing boilers with heat pumps, only funds work in existing homes.

After conducting several case studies of old homes with “air-source” heat pumps – those that draw energy from the outside air – public body Historic England concluded in a report last year that these “work well in a range of different historic building types and uses”.

The UK government-funded “electrification of heat” project took this a step further, stating that “there is no property type or architectural era that is unsuitable for a heat pump”.

Results from the project also indicate that there is no significant variation in performance based on house age.

These findings are not exclusive to the UK. Research organisation the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany carried out extensive field testing and monitoring of heat pumps in existing buildings and concluded that they worked reliably and without problems.

2. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps only work in highly insulated buildings.’

A common – but false – claim is that heat pumps require extremely well insulated buildings to perform properly. For example, Mattie Brignal, senior money reporter at the Daily Telegraph, wrote in October 2023 that good insulation was “crucial” for heat pumps to work:

“Effective insulation is crucial for heat pumps to function optimally because the devices operate at lower temperatures than gas boilers.”

“Heat pumps will never work in Britain,” he claimed, partly because of the UK’s poorly insulated housing. It is indeed true that the UK has one of the worst housing stocks in Europe when it comes to insulation, as data from smart thermostat company tado shows.

Heat pumps can work in any building if sized, designed and installed correctly. Many uninsulated homes and buildings are already heated to comfortable temperatures with heat pumps, as shown across multiple case studies, including an uninsulated stone church.

A building loses heat through the walls, the windows and the roof when it is colder outside than inside, as shown by the stylised arrows in the figure below. The upper panels show an outdoor temperature of 10C, coloured purple, and an indoor temperature of 20C, coloured red.

Without insulation, shown in the left-hand panels, heat loss is higher – indicated by the larger arrows – and the heat input must similarly be increased, in order to maintain a steady indoor temperature.

At lower outside temperatures – shown in the lower panels – more heat is being lost, for a given level of home insulation. Yet as long as the heat input from a heating system is equal to the heat loss, the building will still retain its indoor temperature.

This means that for a poorly insulated home, a larger heat pump is needed, just as a larger gas boiler would be needed to reach the required heat input. For any home, the system is usually designed for the coldest day of the year.

Field research from Germany confirms this stylised representation. One of the longest running field studies of heat pumps in renovated properties shows that extensive renovations and insulation upgrades are not necessary to install a heat pump. Good fabric efficiency will keep running costs down, but this is also true for homes heated by gas and oil boilers.

Heat pumps do usually operate at lower “flow temperatures” to maximise efficiency, which means the water pumped to the radiators in a house will have a temperature closer to 50C or below. Although gas boilers also operate more efficiently at lower flow temperatures, they are typically set to provide water at much higher temperatures of 70C or more.

This means the radiators connected to a heat pump system will be cooler, potentially requiring larger radiators or underfloor heating to achieve the same indoor temperature. Research shows, however, that radiators are often oversized to begin with – and that, as a result, not all radiators may need to be replaced.

Moreover, the market already offers high-temperature heat pumps that can reach flow temperatures of 65C and higher. These can be operated with existing radiators.

Furthermore, the UK government’s electrification of heat UK demonstration project showed that the efficiency of high-temperature heat pumps nears that of standard heat pumps, because they only need to run at higher flow temperatures on the coldest days.

3. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps only work with underfloor heating.’

In a recent survey commissioned by the energy supplier Good Energy, 15% of respondents said they believed heat pumps would require underfloor heating.

This is incorrect. Heat pumps work very well with radiators, too, although the lower flow temperature required by underfloor heating means this radiant heating can make heat pumps work more efficiently.

In some cases, the radiators may need upgrading. However, it has been common practice in recent years for heating installers to oversize radiators to apply large safety margins for providing sufficient heat.

If insulation is installed at a later date, the original radiators will also be larger than required. Some radiators may, therefore, need to be replaced to install a heat pump, but this will depend on the property.

Plenty of properties listed on open-source platform Heat Pump Monitor, which allows individuals to upload key information about their own installations, have heat pumps and old radiators, but no underfloor heating.

Similarly, many properties in the Electrification of Heat project had radiators.

4. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps won’t work in flats.’

The Daily Telegraph reported in October 2023 that “many flats are unsuitable for heat pumps”.

Similarly, in August 2023, the Daily Mail reported the comments of Climate Change Committee chief executive Chris Stark saying it is “very difficult” to install heat pumps in flats.

Finding space for the outside units of air-source heat pumps can indeed be a challenge, when it comes to multi-apartment buildings. Solutions for this problem exist, however, as documented in case studies of blocks of flats using a variety of heat pump technologies including ground, air- and water-source heat pumps.

In the UK, Kensa Contracting has successfully installed ground-source heat pumps in high-rise buildings with hundreds of flats, for example. In this case, a shared “ground loop” circulates water to gather warmth from beneath the ground and this is piped into individual flats via a small, in-home unit, which brings the water up to temperature.

Air-to-air heat pumps – similar to air conditioning units – are also an option for flats.

5. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps don’t work when it’s cold.’

A common criticism of heat pumps is that they purportedly do not work in cold weather. For example, Scottish businessman and Labour peer Lord Haughey was quoted last year in the Times saying that heat pumps cannot cope with the cold climate in Scotland. This story was also widely reported in the Daily Telegraph and the Daily Express.

However, the Nordic region – particularly Sweden, Finland and Norway – suggests otherwise. These three countries have the highest heat pump sales per 1,000 households on the continent. Sweden, Norway and Finland also have the coldest climates in Europe.

In all three countries, there are now more than 40 heat pumps per 100 households, more than in any other country in the world. Heat pump installations started to pick up 20 years ago and have significantly reduced carbon emissions in those countries.

Indeed, European countries with the coldest winters have the highest rates of heat pump sales, as shown in the figure below.

Some also raise questions about how well heat pumps perform when temperatures drop below freezing. For example, climate-sceptic commentator Ross Clark claimed in the Daily Telegraph in January 2024 that “heat pumps seem destined to make us freeze” and that “there is no point in telling us we’ve got to get to net-zero if you can’t tell us how we cope when we reach sub-zero”.

Real-world evidence contradicts such claims. Various field studies have collected performance data of heat pumps, for example on air-source heat pumps in Switzerland, Germany, the UK, the US, Canada and China.

Indeed, heat pumps remain more than twice as efficient as gas boilers, even at temperatures well below freezing, according to peer-reviewed analysis by the Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP).

The analysis found that while the coefficient of performance (COP), which is a measure of how efficiently a heat pump operates, declines as outside temperature falls, it remains high.

The COP compares the amount of energy put into a heating system with the amount that it puts out as useful heat, to warm the home. A COP of 1 means that each unit of energy used to run the system returns 1 unit of heat – corresponding to 100% efficiency.

Fossil fuel boilers are never 100% efficient because some of the heat is lost with flue gases. Instead, gas boilers typically operate at around 85% efficiency, equivalent to a COP of 0.85.

In contrast, heat pumps use electricity to gather extra heat from the outside air or ground, meaning they typically generate at least 2 units of heat for each unit of input. This means they can have a COP of 2 or above, meaning they are 200%, 300% or even more efficient.

As the graph below shows, even on the coldest winter days when temperatures drop to as low as -20C, a standard air-source heat pump can still operate with a COP of around 2. This is significantly higher than fossil fuel and electric boilers, which operate at COPs of less than or equal to 1, respectively.

For locations with regular frigid temperatures, cold-climate heat pumps are available on the market today. These heat pumps use refrigerants that have a lower boiling point than standard models and are suitable for winters down to -26C.

However, for very cold temperatures far below freezing (-20C or below), systems with some form of backup may be needed. In the Nordic countries this is common.

Ground-source heat pumps may also be useful in colder climates, because the ground retains heat over winter and very rarely reaches such low temperatures as the air.

6. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps will always need a backup heating system to keep you warm.‘

It is often claimed that heat pumps require a secondary heating system to provide backup.

For example, a 2023 Daily Mail article reported the experience of one homeowner who had installed backup oil-fired heating to “kick in during winter when the [heat] pumps don’t work efficiently”, while another said they needed backup to make their home “cosy again”.

Yet some 79% of the homes monitored under the UK’s electrification of heat project have no backup heating system and use a heat pump to provide all of their hot water and space heating needs.

(Some homes involved in the project trialled “hybrid” heating systems, with heat pumps providing heating and a gas boiler providing hot water and extra heating capacity.)

As explained above, a complementary heat source might be needed in very cold climates where winter temperatures routinely fall below -20C. But, generally, this does not apply to the UK and other temperate countries.

7. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps won’t keep you warm.’

A variation on the false claim that heat pumps are unable to operate in cold climates is the similarly inaccurate idea that they will not be able to keep homes sufficiently warm.

“You can’t find an engineer prepared to install one of the devices in your home because, in all honesty, they know it wouldn’t actually keep you warm,” claimed Ross Clark in the Daily Telegraph last year.

There is no evidence to support the claim that heat pumps will not keep homes warm. If designed and installed correctly, heat pumps can provide the same levels of comfort as a fossil fuel heating system, or more.

In a survey carried out in the UK on behalf of charity Nesta, more than 80% of people stated that they are satisfied with the ability of their heat pump to provide space and hot water heating. This is a satisfaction level similar to households with gas boilers, Nesta said.

Evidence from other countries provides further support. Some 81% of respondents to a pan-European survey in 2022 indicated that their level of comfort had improved after getting a heat pump.

8. INCOMPLETE: ‘You will freeze during a power cut and be better off with a gas boiler.’

In another article attacking heat pumps, published in January 2024, climate-sceptic columnist Ross Clark warned in the Daily Telegraph that “a power cut lasting more than a few hours will be a very serious matter for communities, which face being totally cut off, shivering”.

Similarly, the Daily Express states heat pump owners have been issued a “horror warning over blackouts”. It quotes Erica Malkin from the Stove Industry Alliance who instead suggests “having a wood-burning stove would certainly mean that people have the ability to heat their homes in the event of a blackout”.

It is correct that a heat pump will not work during a power cut. But the same is the case for gas boilers, which require electricity for controls and to pump hot water through your radiators.

Boiler Central, an online boiler sales company, states on its website that “most” boilers are unable to function without power, such that power cuts render them “temporarily useless”:

“Most modern boilers are reliant on electricity to function, so when the power goes out, your boiler will not be able to heat your home. Without electricity, most of the main components like the thermostat, central heating pumps, and valves will have no power therefore causing your boiler not working properly, rendering your boiler temporarily useless.”

It is also worth noting that the UK’s power grid is very reliable. Most customers only experience a few minutes of outages each year, as data by the energy regulator Ofgem indicates. The same is true in Germany and most other developed countries.

(In the US, power outages are significantly longer – lasting a total of 5 hours on average in 2022 – mainly caused by falling trees.)

9. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps are noisy.’

Another of the false arguments frequently thrown at heat pumps is the idea that they are “too loud” to be installed in many homes – or that the noise they create is a nuisance.

For example, the Daily Telegraph reported – inaccurately – in November 2023 that “heat pumps are too loud to be installed in millions of homes in England under the government’s noise guidelines”.

This headline was contradicted by the experts cited in the article. Consultants Apex Acoustics, who led the research, released a statement saying that the headline claim was “an exaggeration” and that, contrary to the article, noise issues were not “insurmountable”. It said:

“The headline claims heat pumps are ‘too noisy’ for millions of British homes. This is an exaggeration. While noise is a valid concern with heat pumps that needs to be addressed, technology improvements and proper installation can mitigate noise issues in most homes. The article presents noise as an insurmountable problem, which is not the case.”

The Daily Telegraph article also claims there will be a “rise in noise complaints” as more heat pumps are installed.

In reality, UK data shows noise complaints about heat pumps are very low. There are only around 100 noise complaints for every 300,000 installations – a rate of 0.03% – according to a survey by noise experts cited in a research paper by Apex Acoustics.

Government-commissioned research confirms this. It says there is a “low incidence of ASHP [air-source heat pump] noise complaints” and adds: “These arose due to poor quality installations, including location and proximity factors.”

Concluding its response to the Daily Telegraph, Apex Acoustics states that “the article spins isolated concerns and worst-case scenarios into an exaggerated narrative against heat pumps”.

It is true that air-source heat pumps generate a certain degree of noise, due to the fan that circulates ambient air around the outdoor unit. But they can be very quiet and “sound emissions from heat pumps were not reported as noticeable” by the majority of respondents in the study commissioned by the UK government.

In the UK there are strict noise limits on heat pumps. The legal noise limit for heat pumps in the UK is 42 decibels. It is measured from the nearest neighbouring property and means the noise limit at the boundary to a neighbour’s property is 42 decibels. This is a similar volume to a refrigerator.

Ground-source heat pumps create no noise outside of the home, given that there is no fan unit required. Inside a home, ground-source heat pumps do not make more noise than a standard fridge or freezer, says a review by the Federation of Master Builders.

10. INCOMPLETE: ‘Heat pumps cost more to run and will increase heating bills.’

One of the most widespread lines of attack against heat pumps is that they are expensive to run. On the contrary, thanks to their high efficiency, well-designed systems can save UK households hundreds of pounds a year, even though electricity is more expensive than gas.

They offer even greater relative savings in other countries, where electricity prices compared to gas prices are lower.

In a YouTube video from the “Skill Builder” channel, watched more than 2.2m times, presenter Roger Bisby claims “when you look at people’s fuel bills, running a heat pump is roughly three times more expensive than running a gas boiler”. This statement is false.

The running costs of heat pumps relative to gas boilers depend on energy prices and the efficiency of the heat pump installation.

It is a fact that electricity prices are higher than gas prices. Under the UK energy price cap as of March 2024, each unit of electricity is four times more expensive than gas.

However, heat pumps use about 3-5 times less energy compared to a gas boiler. This is because a heat pump turns one unit of electricity into 2.5-5 units of heat.

This efficiency is measured by the seasonal coefficient of performance (SCoP). The SCoP provides a metric to measure the efficiency of a heat pump over the course of a year, rather than the COP which relates to a single moment in time. It measures the total amount of heat produced in a year, compared with the total amount of electricity consumed.

For example, a SCoP of three indicates that for every unit of electricity consumed in a year, the heat pump provides three units of heat. A SCoP of 4 means that the heat pump delivers four times more heat than the electricity input.

In addition, if the heat pump is also used to produce hot water, households can save £110 per year by disconnecting from the gas grid and no longer paying the gas “standing charge”.

In a household paying standard unit prices under the March 2024 UK energy price cap, a heat pump with a SCoP of more than 3 will achieve cost parity with the running costs of an 85% efficient gas boiler.

Under the electrification of heat project, the central estimate (median) SCoP was 2.9. At this level of efficiency, the yearly heating costs to run a heat pump on the current standard tariff would be £25 higher than an 85% gas boiler. Yet much higher heat pump efficiencies can and have been achieved.

HeatGeek, an organisation that trains heat pump installers, reports that installations by those it has trained achieve SCoPs of 4. With a SCoP of 4, households on a standard tariff would save 25% on their heating bills compared to an average gas boiler.

This may change depending on how prices develop in the future, but government estimates suggest that unit prices for electricity will fall relative to those for gas. In other words, the relative running costs of heat pumps will improve versus gas boilers, if those projections are broadly correct.

In the meantime, heat pump users can lower their operating costs through using dedicated tariffs. Some energy companies offer time-varying prices. For example, Octopus Energy’s “Agile” tariff averaged 17 pence per kilowatt hour (p/kWh) over December 2023 to February 2024. This was significantly below the price cap of 27p/kWh from January to March and 25 p/kWh from April to June 2024.

Octopus also offers a special heat pump tariff called “Octopus Cosy”. From 1 April 2024, this will cost 19.6p/kWh, according to Octopus Energy.

Energy supplier OVO also offers a new heat pump tariff of 15p/kWh, called “Heat Pump Plus”, which reduces the unit price by 44% compared to the price cap. (Note that the OVO offering is contingent on working with heat pump accreditation scheme Heat Geek that only covers part of the market.)

OVO also states that, currently, the offering is limited to the first 100 customers who sign up. Whether or not the OVO offering will be available in the future and, if so, in what form is uncertain.

For a UK home on a given energy tariff, the running costs for a heat pump fall as the system gets more efficient (higher SCoP). This is illustrated in the figure below, showing that a home with a heat pump on the standard tariff for April to June 2024 would have lower running costs than for an 85% gas boiler if the SCoP is 3 or above.

The equivalent figures under a range of different energy tariffs are shown by the curved lines. While the figure includes a line for a 92% efficient gas boiler – the rating given on the label of many modern condensing boilers – data from real homes suggests 85% is more typical.

This analysis shows that homes heated with gas boilers could cut their heating bills in half with a heat pump, if they use the Octopus Agile or OVO tariffs, and if their heat pumps have SCoPs of 4.0 and 3.7, respectively.

11. FALSE. ‘Turning gas to electricity to heat via a heat pump is less efficient than burning gas in a boiler.’

A common misunderstanding is that it would be more efficient to burn gas in a domestic gas boiler, rather than converting it into electricity at a power station and using the electricity to run a heat pump instead.

For example, Conservative MP John Redwood tweeted in March 2024 that this would mean “we end up burning more gas in a power station instead of in gas boilers”.

This is false. A standard 300% efficient heat pump (SCoP of 3) would be able to deliver the same amount of warmth as an average gas boiler while cutting gas demand by two-fifths, even if running on 100% gas-fired electricity.

In a more realistic scenario taking into account the way the UK actually generates electricity, the same heat pump would cut gas demand – and the resulting carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions – by at least three-quarters over the next 15 years.

The late Prof Sir David MacKay, former chief scientific adviser to the then-Department of Energy and Climate Change, explained this clearly back in 2008, in his celebrated book “Sustainable Energy Without the Hot Air”:

“Heat pumps are superior in efficiency to condensing boilers, even if the heat pumps are powered by electricity from a power station burning natural gas.”

This is because a heat pump with a SCoP of 3 uses one unit of electricity to make three of heat. As a result, burning one unit of gas in a power plant at 48.3% average efficiency and taking into account the 8% of electricity lost during transmission results in 1.3 units of heat from a heat pump.

In comparison, a gas boiler in the UK typically operates at 85% efficiency, as shown by the grey area in the left-hand bars in the chart below. This means one unit of gas for heating (left column) results in 0.85 units of heat (second from left).

As a result, a 300% efficient heat pump (second column from right, SCoP 3), even if running 100% on gas-generated electricity (rightmost column), needs about two-fifths less gas to make the same amount of heat (“saving”, yellow hatching).

In reality, instead of running on 100% gas-fired electricity, heat pumps would run on the current electricity mix. In the UK, the share of fossil fuels (black) in total electricity generation was 33% in 2023, as shown in the figure below.

It is also important to note that the share of gas generation in the electricity mix will decline over the coming years. This means that a heat pump would cut CO2 emissions by 77-86% over 15 years compared with a gas boiler, based on UK government guidance.

12. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps will never offset the carbon emissions resulting from making them.’

As with electric vehicles, solar panels or wind turbines, the factories making heat pumps need raw materials and energy, which lead to CO2 emissions.

This results in another common misunderstanding that the CO2 saved by the heat pump during operation will be cancelled out by the emissions created during manufacturing.

A typical response on Twitter when posting about heat pumps is along these lines: “Ripping out a perfectly well functioning gas boiler before the end of its natural life and replacing it with a heat pump is misguided. It won’t reduce much carbon.”

The perception that it makes sense to use a gas boiler until the end of its life before installing a heat pump is widespread. It is based on the belief that the “embodied” carbon emissions of a heat pump are higher than any carbon savings during operation.

Despite the intuitive appeal of this belief, detailed analysis shows it is incorrect. In fact, replacing a gas boiler with a heat pump would save 25-28 tonnes of CO2 equivalent (tCO2e) over a 15-year period, a reduction of more than three-quarters.

According to one peer-reviewed study, it takes 1,563kg of CO2 equivalent (kgCO2e) to manufacture a domestic heat pump. This figure – 1.6tCO2e – can be compared with annual per capita emissions in the UK of 5.6tCO2e in 2023.

The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE) has provided new guidance on embodied carbon, which gives a similar result. Using the CIBSE figures, for a heat pump with a capacity of 7 kilowatts (kW), we can assume embodied carbon of around 1,500kgCO2e – slightly more than 200kgCO2e per kW of capacity.

Now let us compare this to a typical gas boiler. Embodied emissions of the boiler are ignored in the calculation of gas boiler emissions, as we assume the gas boiler is already in place. What we are interested in is how quickly a heat pump install will offset its embodied carbon.

The central estimate for annual gas consumption per household is 12,100 kilowatt hours (kWh), excluding the 2.4% of gas used for cooking. Per kWh of gas used, the boiler emits 183gCO2 based on the UK government’s green book guidance. That is 2,209kgCO2e per year. If we assume the gas boiler runs for another 15 years, it will result in total operational emissions of 33,134kgCO2e.

For comparison, a heat pump has significantly lower operational emissions. Using the more conservative “marginal” emission factors from green book guidance and a SCoP of three, the total operational emissions over 15 years from 2023-2037 are expected to be 6,153kgCO2e.

(Using marginal emission factors assume the heat pump is powered by the marginal source of electricity, which is the last power plant that needs to be switched on to meet overall demand. At present, this is usually a gas plant.)

For average green book emission factors, the heat pump would emit 3,242kgCO2e. Using CIBSE figures for the embodied carbon in its manufacture, the total emissions associated with the new heat pump over 15 years would reach 7,653kgCO2e for marginal and 4,742kgCO2e for average emission factors.

This is a saving of 25,481-28,392kgCO2e compared with the gas boiler (25-28tCO2e).

Overall then, replacing a gas boiler with a heat pump would cut emissions by 77-86%, including the embodied emissions from manufacturing the heat pump. This means the heat pump would offset its embodied carbon after 13 months.

Even under the unrealistic and extreme assumption that manufacturing a heat pump entails 10 times more embodied carbon than thought, it would still generate emissions savings of 36-45% over 15 years when replacing a gas boiler.

Additionally, the emissions estimate for gas excludes upstream emissions associated with gas extraction, processing and transport. Applying a higher estimate of 210kgCO2e/kWh to account for the upstream emissions results in higher carbon savings of 80-87% for a heat pump, compared to an existing gas boiler.

In conclusion: the embodied emissions from a heat pump are offset after a few months. Over the lifetime of the appliance, heat pumps save considerable amounts of carbon emissions compared to a gas boiler.

13. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps devalue properties.’

A common myth suggests that installing a heat pump will devalue your property. For example, an article in the Daily Express from 2022 suggested that “homeowners who are forced to rip out their gas boiler and replace it with eco-friendly heat pumps will see the value of the home collapse”.

The evidence suggests the opposite: heat pumps increase the value of properties. Research from the US found that “residences with an air source heat pump enjoy a 4.3–7.1% (or $10,400–17,000) price premium on average”.

UK research has shown that a heat pump could add between 1.7% and 3.0% to the value of an average home. Estate agent Savills also reports that buyers pay a premium for homes with heat pumps.

Based on the average UK house price in December 2023, some £285,000, this implies a price premium of £4,800-£8,600, which amounts to a significant proportion of the cost of installing a heat pump in the first place.

14. INCOMPLETE: ‘Heat pumps are unaffordable.’

The upfront cost of heat pumps is a frequently cited issue with the technology.

For example, the Daily Telegraph said in a September 2023 article:

“The main barrier to installing these devices for most homes is the disproportionately large upfront cost when compared to traditional heating systems.”

Similarly, yet another Ross Clark comment for the Daily Telegraph – under the headline “The great heat pump hype is almost dead” – said they were “horrendously expensive to install”.

It is true that heat pumps are more expensive to buy than gas boilers.

In 2023, the average installation cost of an air source heat pump in the UK was £12,368, according to MCS data. This compares with £2,500-3,000 for a gas boiler, according to the UK government. A recent report by the National Audit Office concluded that heat pumps have seen a 6% real-terms cost reduction compared to 2021.

The UK government offers subsidies for heat pumps of £7,500 per installation under the boiler upgrade scheme. This is an increase from the previous level of £5,000, leading to a surge in interest, as shown in the figure below.

(The number of applications for heat pump vouchers in January 2024 was 39% higher than a year earlier, the government says.)

Some companies now offer heat pumps for less than £3,000 after the grant, a cost similar to a new gas boiler.

Most forecasts are for heat pump installation costs to decline in the future, according to a systematic review of the evidence by the UK Energy Research Centre. The majority of forecasts suggest a reduction in total installed costs of around 20-25% by 2030, it found.

Crucially, while heat pumps currently have relatively high upfront costs, they are expected to be the most cost-effective way to decarbonise heating.

15. INCOMPLETE: ‘The grid cannot cope with heat pumps.’

Another common myth about heat pumps – as for electric vehicles – is that their widespread adoption would be catastrophic for the electricity grid.

For example, the Daily Express published an article in 2022 titled: “Heat pump hell: Owners sent horror warning over boiler alternatives amid blackout threat.”

The article cites Erica Malkin from the Stove Industry Alliance, the trade association for UK stove manufacturers, installers and retailers. She claimed that the grid may not be able to cope with heat pumps and there could be power outages if they are widely rolled out.

Similarly, a February 2024 comment for the Sunday Telegraph by omnipresent climate-sceptic columnist Ross Clark asked “at a time when politicians want millions more of us to be driving electric cars and heating our homes with heat pumps…how will we keep the lights on?”

Clark also claimed that the plan to electrify heating and transport will “put us all in the dark” and that “the UK is much closer to blackouts than anyone dares to admit”.

In an unrealistic scenario where all UK homes switched to heat pumps overnight, in many areas the electricity grid would indeed struggle. Yet the transition to heat pumps will take decades, not just a couple of years.

This gives the electricity network companies, the future system operator, the energy suppliers and the energy regulator Ofgem time to adjust.

In its latest assessment of UK infrastructure needs, official government advisor the National Infrastructure Commission points to the rapid transformation of the power system in the past. This suggests the UK can build the infrastructure needed to electrify heating within the timescales required, it says.

Moreover, although not widely known, UK electricity demand has fallen by 18% over the last two decades. This has created some space on the grid for demand growth.

The factors driving the drop include product energy efficiency regulations, energy-efficient lighting – which has cut peak demand by the equivalent of roughly two nuclear plants alone – environmentally conscious consumers and economic restructuring, including offshoring energy-intensive industries.

National Grid is well aware of the needed investment in the grid and is planning for heat pumps (and electric vehicles) to be connected. It says it is confident that electrification of home heating can be delivered in the UK.

Distribution network operators, who manage local grids and transmit electricity to individual customers, started to develop heat pump strategies a few years ago.

The amount of unused grid capacity in the distribution grid varies by area. In some parts of the country, there is no need for grid upgrades.

Research carried out on behalf of the UK government found that in rural areas of Scotland, 36-59% of the grid would require upgrades if all heating was electrified.

More recent research predicts that peak heat demand from heat pumps will be 8% lower than for gas heating, because heat pumps are designed to deliver heat consistently over longer periods rather than in short bursts.

In addition, it found that the maximum “heat ramp rate” – the speed at which heating loads increase prior to peak periods – will be 67% lower compared to gas heating.

An important solution for minimising the required grid investments and consumer costs is demand flexibility, or the ability to shift demand to periods when electricity is cheap and the pressure on the grid is lower.

It has been demonstrated that heat pumps can provide demand flexibility to support the grid. This can mean heating buildings slightly before peak periods and ramping down heat pump output during the peak, without a noticeable loss in comfort. It can also mean using “heat batteries” and thermal storage to absorb cheaper electricity when available.

The question of energy system reliability under a net-zero pathway has been looked at extensively by the Committee on Climate Change and the Royal Society. Those assessments found that with an appropriate technology mix, it is possible to electrify much of the UK’s heating at the same time as ensuring reliability of supply.

16. INCOMPLETE: ‘Heat pumps don’t work with microbore piping.’

The Daily Express reported in 2021 that “any homes with microbore pipework looking to install a heat pump…could result in huge costs and major disruption to installing additional equipment. All pipework throughout the properties might also need replacing.”

The article was based on comments from the Heating and Hot Water Industry Council, which, among other organisations, represents boiler companies.

Microbore pipework is a smaller type of pipework often used in homes to transport hot water to radiators. It is a generic term for pipes which measure under 15mm in diameter and are usually made of either plastic or copper.

The lower diameter means it is harder to run hot water around the system quickly.

Heat pump heating systems typically use higher flow rates, in combination with lower flow temperatures, in order to maximise efficiency.

As a result, microbore piping is not ideal for heat pumps. Yet it can still be possible to keep some microbore pipes and still install a heat pump, as explained by Heat Geek.

There are even examples of homes with microbore piping that have had heat pumps installed successfully. Heat pump installer Aira explains how a home with microbore can still benefit from a heat pump, with the right adjustments.

In conclusion, it is correct that microbore pipes are not always ideal for heat pumps. But it is incorrect to say that heat pumps will not work with microbore piping.

17. FALSE: ‘Heat pumps don’t last long.’

Despite persistent claims to the contrary on social media, heat pumps can last a couple decades or even longer. The UK government assumes a lifetime of 20 years in its official impact assessment for heat pump subsidies.

Analysis of field data from the US, collected between 2001 and 2007 by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, concluded that air-to-air heat pumps last on average 15 years – and since then, the quality of the technology has improved.

18. INCOMPLETE: ‘Heat pumps are new and untested technology.’

In a February 2024 article about Scotland’s plans to roll out heat pumps, the Herald reported that the GMB trade union had tabled a motion at the Scottish Labour Party conference against “forcing onto households untested systems such as heat pumps”.

(The “b” in GMB historically stood for “boilermakers”.)

Heat pumps are, however, a very mature technology and have been around for more than 100 years. The first heat pump as we know it today was built by Austrian engineer Peter von Rittinger in 1856. Heat pumps were installed in peoples’ homes many decades ago.

A heat pump was installed in the City Hall of Zurich in 1938 and was not replaced until 2001. The first heat pump in the UK was installed in Norwich in 1945 by John Sumner, the city electrical engineer for Norwich.

Across the world, there are close to 200m heat pumps in operation today.

The post Factcheck: 18 misleading myths about heat pumps appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of America’s Broken Health Care System

American farmers are drowning in health insurance costs, while their German counterparts never worry about medical bills. The difference may help determine which country’s small farms are better prepared for a changing climate.

Samantha Kemnah looked out the foggy window of her home in New Berlin, New York, at the 150-acre dairy farm she and her husband, Chris, bought last year. This winter, an unprecedented cold front brought snowstorms and ice to the region.

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of the Broken U.S. Health Care System

Climate Change

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Two Utah Congress members have introduced a resolution that could end protections for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Conservation groups worry similar maneuvers on other federal lands will follow.

Lawmakers from Utah have commandeered an obscure law to unravel protections for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, potentially delivering on a Trump administration goal of undoing protections for public conservation lands across the country.

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Climate Change

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

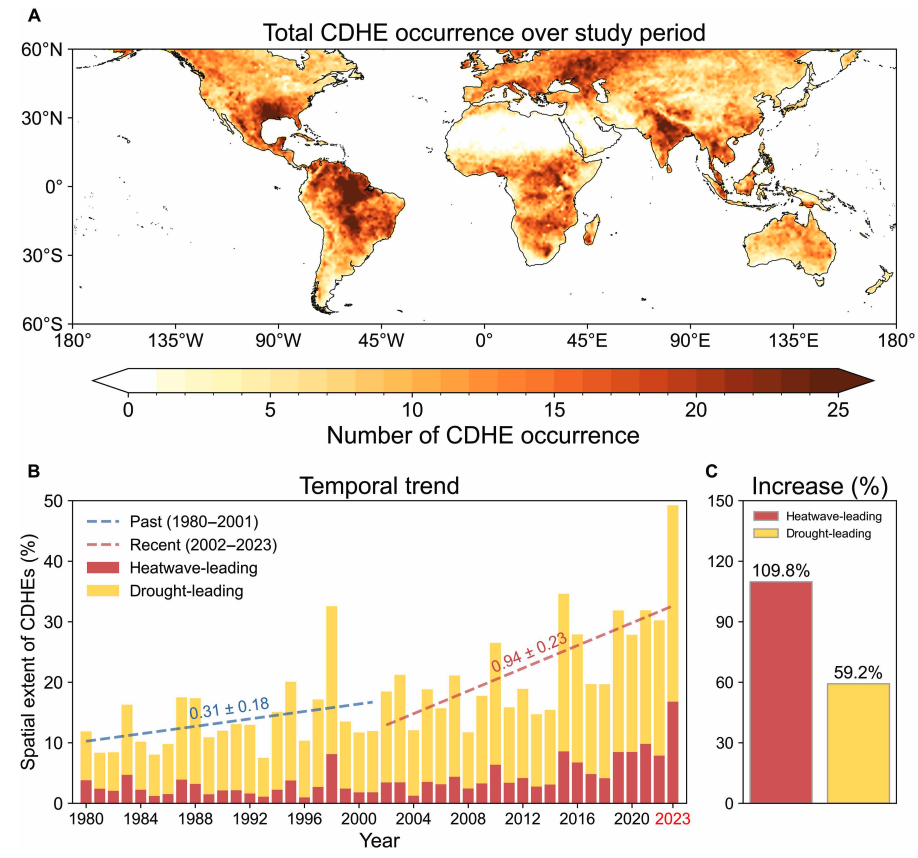

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits