Welcome to Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.

China Briefing handpicks and explains the most important climate and energy stories from China over the past fortnight. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Record power and gas demand

DOMESTIC TURBINES: China’s top economic planning body, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), expects both electricity demand and gas demand to hit the “highest level yet recorded in winter”, reported Reuters. Data from a sample of coal plants nevertheless showed a recent drop in output year-on-year. Meanwhile, China has developed a “high-efficiency” gas turbine which will “strengthen[ China’s] power grid with low-carbon electricity”, said state news agency Xinhua. According to Bloomberg, the turbine is the first to have been fully produced in China, helping the country to “reduce reliance on imported technology amid a global shortage of equipment”.

‘SUBDUED’ OIL GROWTH: Chinese oil demand is likely to “remain subdued” until at least the middle of 2026, reported Bloomberg. Next year will see “one of the lowest growth rates in China in quite some time”, said commodities trader Trafigura’s chief economist Saad Rahim, reported the Financial Times. Demand is set to plateau until 2030, according to research linked to “state oil major” CNPC, said Reuters. In the building materials industry, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are “projected to fall by 25%” in 2025 relative to pre-2021 levels, China Building Materials Federation president Yan Xiaofeng told state broadcaster CCTV.

FLAT EMISSIONS GROWTH: China’s CO2 emissions in 2024 grew by 0.6% year-on-year, reported Xinhua, citing the newly released China Greenhouse Gas Bulletin (2024). This represented a “significant narrowing from the 2023 increase and remains below the global average growth rate of 0.8%”, it added. (The bulletin confirms analysis for Carbon Brief published in January, which put China’s 2024 emissions growth at 0.8%.)

China-France climate statements

CLIMATE BONHOMIE: During a visit by French president Emmanuel Macron to China, the two countries signed a joint statement on climate change, reported Xinhua. It published the full text of the statement, which pledged more cooperation on “accelerating” renewables globally, as well as “enhancing communication” in carbon pricing, methane, adaptation and other areas. It also said China and France would support developing countries’ access to climate finance, adding that developed nations will “take the lead in providing and mobilising” this “before 2035”, while encouraging developing countries to “voluntarily contribute”.

MORE COOPERATION: China and France issued separate statements on “nuclear energy” cooperation, Xinhua reported, as well as on expanding cooperation on the “green economy”, according to the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post.

EU’s new ‘economic security’ package

NEW PLANS, SAME TOOLS: Meanwhile, the EU has issued new plans to “boost EU resilience to threats like rare-earth shortages”, said Reuters, including an “economic security doctrine” that would encourage “new measures…designed to counter unfair trade and market distortions, including overcapacity”. A second plan on critical minerals will “restrict exports of [recyclable] rare-earth waste and battery scrap” to shore up supplies for “electric cars, wind turbines and semiconductors”, according to another Reuters article. Euractiv characterised the policy package as a “reframing of existing tools and plans”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “China Briefing” email newsletter. All you need to know about the latest developments relating to China and climate change. Sent to your inbox every Thursday.

‘NOT VERY CREDIBLE’: EU climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra told the Financial Times that the latest push against the bloc’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), which the outlet said is “led by China, India and Saudi Arabia”, was “not very credible”. A “GT Voice” comment in the state-supporting Global Times said the CBAM exposed a dilemma around the “absence of a globally accepted, transparent and equitable standard for measuring carbon footprints”. It called CBAM a “pioneering step”, but said climate efforts needed “greater international coordination, not unilateral enforcement”.

FIRST REVIEW: The EU has undertaken its first “formal review” of the tariffs placed on Chinese-made electric vehicles (EVs), assessing a price undertaking offer submitted by Volkswagen’s Chinese joint venture, reported SCMP. Chinese EVs – including both hybrid and pure EVs – saw their “second-best month on record” in October, with sales coming down slightly from September’s peak, said Bloomberg.

More China news

- ECONOMIC SIGNALS: At the central economic work conference, held in Beijing on 10-11 December, President Xi Jinping said China would adhere to the “dual-carbon” goals and promote a “comprehensive green transition”, reported Xinhua.

- EFFORTS ‘INTENSIFIED’: Ahead of the meeting, premier Li Qiang also noted earlier that energy conservation and carbon reduction efforts must be “intensified”, according to the People’s Daily.

- JET FUEL: A major jet fuel distributor is being acquired by oil giant Sinopec, which could “risk slowing [China’s] push to decarbonise air travel”, reported Caixin.

- SLOW AND STEADY: An article in the People’s Daily said China’s energy transition is “not something that can be achieved overnight”.

- ‘ECO-POLICE’: China’s environment ministry published a draft grading system for “atmospheric environmental performance in key industries”, including assessment of “significant…carbon emission reduction effects”, noted International Energy Net. China will also set up an “eco-police” mechanism in 2027, China Daily said.

- INNOVATION INITIATIVE: The National Energy Administration issued a call for the “preliminary establishment of a new energy system that is clean, low-carbon, safe and efficient” in the next five years, reported BJX News. The plan also noted: “Those who take the lead in [energy technology] innovation will gain the initiative.”

Spotlight

Interview: How ‘mid-level bureaucrats’ are helping to shape Chinese climate policy

Local officials are viewed as relatively weak actors in China’s governance structure.

However, a new book – “Implementing a low-carbon future: climate leadership in Chinese cities” – argues that these officials play an important role in designing innovative and enduring climate policy.

Carbon Brief interviews author Weila Gong, non-resident scholar at the UC San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy’s 21st Century China Center and visiting scholar at UC Davis, on her research.

Below are highlights from the conversation. The full interview is published on the Carbon Brief website.

Carbon Brief: You’ve just written a book about climate policy in Chinese cities. Could you explain why subnational governments are important for China’s climate policy in general?

Weila Gong: China is the world’s largest carbon emitter [and] over 85% of China’s carbon emissions come from cities.

We tend to think that officials at the provincial, city and township levels are barriers for environmental protection, because they are focused on promoting economic growth.

But I observed these actors participating in China’s low-carbon city pilot. I was surprised to see so many cities wanted to participate, even though there was no specific evaluation system that would reward their efforts.

CB: Could you help us understand the mindset of these bureaucrats? How do local-level officials design policies in China?

WG: We tend to focus on top political figures, such as mayors or [municipal] party secretaries. But mid-level bureaucrats [are usually the] ones implementing low-carbon policies.

Mid-level local officials saw [the low-carbon city pilot] as a way to help their bosses get promoted, which in turn would help them advance their own career. As such, they [aimed to] create unique, innovative and visible policy actions to help draw the attention [of their superiors].

They are also often more interested in climate issues if it is in the interest of their agency or local government.

Another motivation is accessing finance [by using] pilot programmes, if their ideas impress the central-level government.

CB: Could you give an example of what drives innovative local climate policies?

WG: National-level policies and pilot programme schemes provide openings for local governments to think about how and whether they should engage more in addressing climate change.

By experiment[ing] with policy at a local level, local governments help national-level officials develop responses to emerging policy challenges.

Local carbon emission trading systems (ETSs) are an example.

One element that made the Shenzhen ETS successful is “entrepreneurial bureaucrats” [who have the ability to design, push through and maintain new local-level climate policies].

Even though we might think local officials are constrained in terms of policy or financial resources, they often have the leverage and space to build coalitions…and know how to mobilise political support.

CB: What needs to be done to strengthen sub-national climate policy making?

WG: It’s very important to have groups of personnel trained on climate policy…[Often] climate change is only one of local officials’ day-to-day responsibilities. We need full-time staff to follow through on policies from the beginning right up to implementation.

Secondly, while almost all cities have made carbon-peaking plans, one area in which the government can make further progress is data.

Most Chinese cities haven’t yet established regular carbon accounting systems, [and only have access to] inadequate statistics. Local agencies can’t always access detailed data [held at the central level]…[while] much of the company-level data is self-reported.

Finally, China will always need local officials willing to try new policy instruments. Ensuring they have the conditions to do this is very important.

Watch, read, listen

BREAKNECK SPEED: In a conversation with the Zero podcast, tech analyst Dan Wang outlined how an “engineering mindset” may have given China the edge in developing clean-energy systems in comparison to the US.

QUESTION OF CURRENCY: Institute of Finance and Sustainability president Ma Jun and Climate Bonds Initiative CEO Sean Kidney examined how China’s yuan-denominated loans can “ease the climate financing crunch” in the South China Morning Post.

DRIVING CHANGE: Deutsche Welle broadcast a report on how affordable cleantech from China is accelerating the energy transition in global south countries.

EXPOSING LOOPHOLES: Economic news outlet Jiemian investigated how a scandal involving the main developer of pumped storage capacity in China revealed “regulatory loopholes” in constructing such projects.

$180 billion

The amount of outward direct investment Chinese companies have committed to cleantech projects overseas since 2023, according to a new report by thinktank Climate Energy Finance.

New science

- A new study looking at battery electric trucks across China, Europe and the US showed they “can reach 27-58% reductions in lifecycle CO2 emissions compared with diesel trucks” | Nature Reviews Clean Technology

- “Shortcomings remain” in China’s legal approach to offshore carbon capture, utilisation and storage, such as a lack of “specialised” legal frameworks | Climate Policy

China Briefing is written by Anika Patel and edited by Simon Evans. Please send tips and feedback to china@carbonbrief.org

The post China Briefing 11 December 2025: Winter record looms; Joint climate statement with France; How ‘mid-level bureaucrats’ help shape policy appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 6 February 2026: US secret climate panel ‘unlawful’ | China’s clean energy boon | Can humans reverse nature loss?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Secrets and layoffs

UNLAWFUL PANEL: A federal judge ruled that the US energy department “violated the law when secretary Chris Wright handpicked five researchers who rejected the scientific consensus on climate change to work in secret on a sweeping government report on global warming”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper explained that a 1972 law “does not allow agencies to recruit or rely on secret groups for the purposes of policymaking”. A Carbon Brief factcheck found more than 100 false or misleading claims in the report.

DARKNESS DESCENDS: The Washington Post reportedly sent layoff notices to “at least 14” of its climate journalists, as part of a wider move from the newspaper’s billionaire owner, Jeff Bezos, to eliminate 300 jobs at the publication, claimed Climate Colored Goggles. After the layoffs, the newspaper will have five journalists left on its award-winning climate desk, according to the substack run by a former climate reporter at the Los Angeles Times. It comes after CBS News laid off most of its climate team in October, it added.

WIND UNBLOCKED: Elsewhere, a separate federal ruling said that a wind project off the coast of New York state can continue, which now means that “all five offshore wind projects halted by the Trump administration in December can resume construction”, said Reuters. Bloomberg added that “Ørsted said it has spent $7bn on the development, which is 45% complete”.

Around the world

- CHANGING TIDES: The EU is “mulling a new strategy” in climate diplomacy after struggling to gather support for “faster, more ambitious action to cut planet-heating emissions” at last year’s UN climate summit COP30, reported Reuters.

- FINANCE ‘CUT’: The UK government is planning to cut climate finance by more than a fifth, from £11.6bn over the past five years to £9bn in the next five, according to the Guardian.

- BIG PLANS: India’s 2026 budget included a new $2.2bn funding push for carbon capture technologies, reported Carbon Brief. The budget also outlined support for renewables and the mining and processing of critical minerals.

- MOROCCO FLOODS: More than 140,000 people have been evacuated in Morocco as “heavy rainfall and water releases from overfilled dams led to flooding”, reported the Associated Press.

- CASHFLOW: “Flawed” economic models used by governments and financial bodies “ignor[e] shocks from extreme weather and climate tipping points”, posing the risk of a “global financial crash”, according to a Carbon Tracker report covered by the Guardian.

- HEATING UP: The International Olympic Committee is discussing options to hold future winter games earlier in the year “because of the effects of warmer temperatures”, said the Associated Press.

54%

The increase in new solar capacity installed in Africa over 2024-25 – the continent’s fastest growth on record, according to a Global Solar Council report covered by Bloomberg.

Latest climate research

- Arctic warming significantly postpones the retreat of the Afro-Asian summer monsoon, worsening autumn rainfall | Environmental Research Letters

- “Positive” images of heatwaves reduce the impact of messages about extreme heat, according to a survey of 4,000 US adults | Environmental Communication

- Greenland’s “peripheral” glaciers are projected to lose nearly one-fifth of their total area and almost one-third of their total volume by 2100 under a low-emissions scenario | The Cryosphere

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

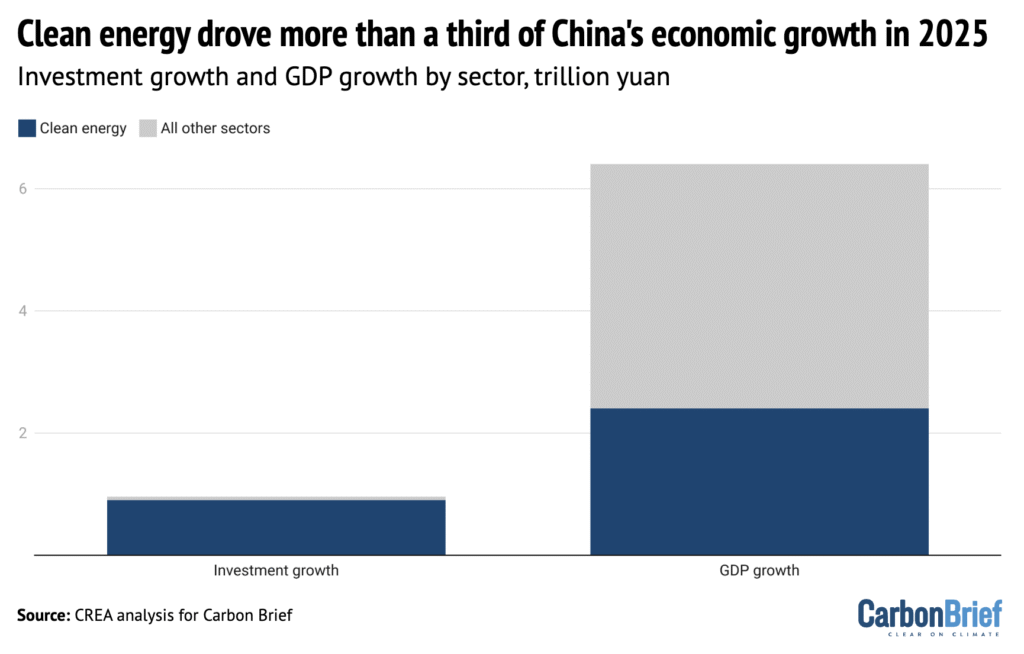

Solar power, electric vehicles and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment, according to new analysis for Carbon Brief (shown in blue above). Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) – comparable to the economies of Brazil or Canada, the analysis said.

Spotlight

Can humans reverse nature decline?

This week, Carbon Brief travelled to a UN event in Manchester, UK to speak to biodiversity scientists about the chances of reversing nature loss.

Officials from more than 150 countries arrived in Manchester this week to approve a new UN report on how nature underpins economic prosperity.

The meeting comes just four years before nations are due to meet a global target to halt and reverse biodiversity loss, agreed in 2022 under the landmark “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (GBF).

At the sidelines of the meeting, Carbon Brief spoke to a range of scientists about humanity’s chances of meeting the 2030 goal. Their answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Dr David Obura, ecologist and chair of Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)

We can’t halt and reverse the decline of every ecosystem. But we can try to “bend the curve” or halt and reverse the drivers of decline. That’s the economic drivers, the indirect drivers and the values shifts we need to have. What the GBF aspires to do, in terms of halting and reversing biodiversity loss, we can put in place the enabling drivers for that by 2030, but we won’t be able to do it fast enough at this point to halt [the loss] of all ecosystems.

Dr Luthando Dziba, executive secretary of IPBES

Countries are due to report on progress by the end of February this year on their national strategies to the Convention on Biological Diversity [CBD]. Once we get that, coupled with a process that is ongoing within the CBD, which is called the global stocktake, I think that’s going to give insights on progress as to whether this is possible to achieve by 2030…Are we on the right trajectory? I think we are and hopefully we will continue to move towards the final destination of having halted biodiversity loss, but also of living in harmony with nature.

Prof Laura Pereira, scientist at the Global Change Institute at Wits University, South Africa

At the global level, I think it’s very unlikely that we’re going to achieve the overall goal of halting biodiversity loss by 2030. That being said, I think we will make substantial inroads towards achieving our longer term targets. There is a lot of hope, but we’ve also got to be very aware that we have not necessarily seen the transformative changes that are going to be needed to really reverse the impacts on biodiversity.

Dr David Cooper, chair of the UK’s Joint Nature Conservation Committee and former executive secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity

It’s important to look at the GBF as a whole…I think it is possible to achieve those targets, or at least most of them, and to make substantial progress towards them. It is possible, still, to take action to put nature on a path to recovery. We’ll have to increasingly look at the drivers.

Prof Andrew Gonzalez, McGill University professor and co-chair of an IPBES biodiversity monitoring assessment

I think for many of the 23 targets across the GBF, it’s going to be challenging to hit those by 2030. I think we’re looking at a process that’s starting now in earnest as countries [implement steps and measure progress]…You have to align efforts for conserving nature, the economics of protecting nature [and] the social dimensions of that, and who benefits, whose rights are preserved and protected.

Neville Ash, director of the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre

The ambitions in the 2030 targets are very high, so it’s going to be a stretch for many governments to make the actions necessary to achieve those targets, but even if we make all the actions in the next four years, it doesn’t mean we halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. It means we put the action in place to enable that to happen in the future…The important thing at this stage is the urgent action to address the loss of biodiversity, with the result of that finding its way through by the ambition of 2050 of living in harmony with nature.

Prof Pam McElwee, Rutgers University professor and co-chair of an IPBES “nexus assessment” report

If you look at all of the available evidence, it’s pretty clear that we’re going to keep experiencing biodiversity decline. I mean, it’s fairly similar to the 1.5C climate target. We are not going to meet that either. But that doesn’t mean that you slow down the ambition…even though you recognise that we probably won’t meet that specific timebound target, that’s all the more reason to continue to do what we’re doing and, in fact, accelerate action.

Watch, read, listen

OIL IMPACTS: Gas flaring has risen in the Niger Delta since oil and gas major Shell sold its assets in the Nigerian “oil hub”, a Climate Home News investigation found.

LOW SNOW: The Washington Post explored how “climate change is making the Winter Olympics harder to host”.

CULTURE WARS: A Media Confidential podcast examined when climate coverage in the UK became “part of the culture wars”.

Coming up

- 2-8 February: 12th session of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), Manchester, UK

- 8 February: Japanese general election

- 8 February: Portugal presidential election

- 11 February: Barbados general election

- 11-12 February: UN climate chief Simon Stiell due to speak in Istanbul, Turkey

Pick of the jobs

- UK Met Office, senior climate science communicator | Salary: £43,081-£46,728. Location: Exeter, UK

- Canadian Red Cross, programme officer, Indigenous operations – disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation | Salary: $56,520-$60,053. Location: Manitoba, Canada

- Aldersgate Group, policy officer | Salary: £33,949-£39,253. Location: London (hybrid)

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 6 February 2026: US secret climate panel ‘unlawful’ | China’s clean energy boon | Can humans reverse nature loss? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean energy’s share of economy | Record renewables | Thawing relations with UK

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.

China Briefing handpicks and explains the most important climate and energy stories from China over the past fortnight. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Solar and wind eclipsed coal

‘FIRST TIME IN HISTORY’: China’s total power capacity reached 3,890 gigawatts (GW) in 2025, according to a National Energy Administration (NEA) data release covered by industry news outlet International Energy Net. Of this, it said, solar capacity rose 35% to 1,200GW and wind capacity was up 23% to 640GW, while thermal capacity – which is mostly coal – grew 6% to just over 1,500GW. This marks the “first time in history” that wind and solar capacity has outranked coal capacity in China’s power mix, reported the state-run newspaper China Daily. China’s grid-related energy storage capacity exceeded 213GW in 2025, said state news agency Xinhua. Meanwhile, clean-energy industries “drove more than 90%” of investment growth and more than half of GDP growth last year, said the Guardian in its coverage of new analysis for Carbon Brief. (See more in the spotlight below.)

DAWN FOR SOLAR: Solar power capacity alone may outpace coal in 2026, according to projections by the China Electricity Council (CEC), reported business news outlet 21st Century Business Herald. It added that non-fossil sources could account for 63% of the power mix this year, with coal falling to 31%. Separately, the China Renewable Energy Society said that annual wind-power additions could grow by between 600-980GW over the next five years, with annual additions of 120GW expected until 2028, said industry news outlet China Energy Net. China Energy Net also published the full CEC report.

STATE MEDIA VOICE: Xinhua published several energy- and climate-related articles in a series on the 15th five-year plan. One said that becoming a low-carbon energy “powerhouse” will support decarbonisation efforts, strengthen industrial innovation and improve China’s “global competitive edge and standing”. Another stated that coal consumption is “expected” to peak around 2027, with continued “growth” in the power and chemicals sector, while oil has already peaked. A third noted that distributed energy systems better matched the “characteristics of renewable energy” than centralised ones, but warned against “blind” expansion and insufficient supporting infrastructure. Others in the series discussed biodiversity and environmental protection and recycling of clean-energy technology. Meanwhile, the communist party-affiliated People’s Daily said that oil will continue to play a “vital role” in China, even after demand peaks.

Starmer and Xi endorsed clean-energy cooperation

CLIMATE PARTNERSHIP: UK prime minister Keir Starmer and Chinese president Xi Jinping pledged in Beijing to deepen cooperation on “green energy”, reported finance news outlet Caixin. They also agreed to establish a “China-UK high-level climate and nature partnership”, said China Daily. Xi told Starmer that the two countries should “carry out joint research and industrial transformation” in new energy and low-carbon technologies, according to Xinhua. It also cited Xi as saying China “hopes” the UK will provide a “fair” business environment for Chinese companies.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “China Briefing” email newsletter. All you need to know about the latest developments relating to China and climate change. Sent to your inbox every Thursday.

OCTOPUS OVERSEAS: During the visit, UK power-trading company Octopus Energy and Chinese energy services firm PCG Power announced they would be starting a new joint venture in China, named Bitong Energy, reported industry news outlet PV Magazine. The move “marks a notable direct entry” of a foreign company into China’s “tightly regulated electricity market”, said Caixin.

PUSH AND PULL: UK policymakers also visited Chinese clean-energy technology manufacturer Envision in Shanghai, reported finance news outlet Yicai. It quoted UK business secretary Peter Kyle emphasising that partnering with companies “like Envision” on sustainability is a “really important part of our future”, particularly in terms of job creation in the UK. Trade minister Chris Bryant told Radio Scotland Breakfast that the government will decide on Chinese wind turbine manufacturer Mingyang’s plans for a Scotland factory “soon”. Researchers at the thinktank Oxford Institute for Energy Studies wrote in a guest post for Carbon Brief that greater Chinese competition in Europe’s wind market could “help spur competition in Europe”, if localisation rules and “other guardrails” are applied.

More China news

- LIFE SUPPORT: China will update its coal capacity payment mechanism, which will raise thresholds for coal-fired power plants and expand to cover gas-fired power and pumped and new-energy storage, reported current affairs outlet China News.

- FRONTIER TECH: The world’s “largest compressed-air power storage plant” has begun operating in China, said Bloomberg.

- PARTNERSHIP A ‘MISTAKE’: The EU launched a “foreign subsidies” probe into Chinese wind turbine company Goldwind, said the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. EU climate chief Wopke Hoekstra said the bloc must resist China’s pull in clean technologies, according to Bloomberg.

- TRADE SPAT: The World Trade Organization “backed a complaint by China” that the US Inflation Reduction Act “discriminated against” Chinese cleantech exports, said Reuters.

- NEW RULES: China has set “new regulations” for the Waliguan Baseline Observatory, which provides “key scientific references for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change”, said the People’s Daily.

Captured

New or reactivated proposals for coal-fired power plants in China totalled 161GW in 2025, according to a new report covered by Carbon Brief.

Spotlight

Clean energy drove China’s economic growth in 2025

New analysis for Carbon Brief finds that clean-energy sectors contributed the equivalent of $2.1tn to China’s economy last year, making it a key driver of growth. However, headwinds in 2026 could restrict growth going forward – especially for the solar sector.

Below is an excerpt from the article, which can be read in full on Carbon Brief’s website.

Solar power, electric vehicles (EVs) and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment.

Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP)

Analysis shows that China’s clean-energy sectors nearly doubled in real value between 2022-25 and – if they were a country – would now be the 8th-largest economy in the world.

These investments in clean-energy manufacturing represent a large bet on the energy transition in China and overseas, creating an incentive for the government and enterprises to keep the boom going.

However, there is uncertainty about what will happen this year and beyond, particularly due to a new pricing system, worsening industrial “overcapacity” and trade tensions.

Outperforming the wider economy

China’s clean-energy economy continues to grow far more quickly than the wider economy, making an outsized contribution to annual growth.

Without these sectors, China’s GDP would have expanded by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%, missing the target of “around 5%” growth by a wide margin.

Clean energy made a crucial contribution during a challenging year, when promoting economic growth was the foremost aim for policymakers.

In 2024, EVs and solar had been the largest growth drivers. In 2025, it was EVs and batteries, which delivered 44% of the economic impact and more than half of the growth of the clean-energy industries.

The next largest subsector was clean-power generation, transmission and storage, which made up 40% of the contribution to GDP and 30% of the growth in 2025.

Within the electricity sector, the largest drivers were growth in investment in wind and solar power generation capacity, along with growth in power output from solar and wind, followed by the exports of solar-power equipment and materials.

But investment in solar-panel supply chains, a major growth driver in 2022-23, continued to fall for the second year, as the government made efforts to rein in overcapacity and “irrational” price competition.

Headwinds for solar

Ongoing investment of hundreds of billions of dollars represents a gigantic bet on a continuing global energy transition.

However, developments next year and beyond are unclear, particularly for solar. A new pricing system for renewable power is creating uncertainty, while central government targets have been set far below current rates of clean-electricity additions.

Investment in solar-power generation and solar manufacturing declined in the second half of the year.

The reduction in the prices of clean-energy technology has been so dramatic that when the prices for GDP statistics are updated, the sectors’ contribution to real GDP – adjusted for inflation or, in this case deflation – will be revised down.

Nevertheless, the key economic role of the industry creates a strong motivation to keep the clean-energy boom going. A slowdown in the domestic market could also undermine efforts to stem overcapacity and inflame trade tensions by increasing pressure on exports to absorb supply.

Local governments and state-owned enterprises will also influence the outlook for the sector.

Provincial governments have a lot of leeway in implementing the new electricity markets and contracting systems for renewable power generation. The new five-year plans, to be published this year, will, therefore, be of major importance.

This spotlight was written for Carbon Brief by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), and Belinda Schaepe, China policy analyst at CREA. CREA China analysts Qi Qin and Chengcheng Qiu contributed research.

Watch, read, listen

PROVINCE INFLUENCE: The Institute for Global Decarbonization Progress, a Beijing-based thinktank, published a report examining the climate-related statements in provincial recommendations for the 15th five-year plan.

‘PIVOT’?: The Outrage + Optimism podcast spoke with the University of Bath’s Dr Yixian Sun about whether China sees itself as a climate leader and what its role in climate negotiations could be going forward.

COOKING FOR CLEAN-TECH: Caixin covered rising demand for China’s “gutter oil” as companies “scramble” to decarbonise.

DON’T GO IT ALONE: China News broadcast the Chinese foreign ministry’s response to the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement, with spokeswoman Mao Ning saying “no country can remain unaffected” by climate change.

$6.8tn

The current size of China’s green-finance economy, including loans, bonds and equity, according to Dr Ma Jun, the Institute of Finance and Sustainability’s president,in a report launch event attended by Carbon Brief. Dr Ma added that “green loans” make up 16% of all loans in China, with some areas seeing them take a 34% share.

New science

- China’s official emissions inventories have overestimated its hydrofluorocarbon emissions by an average of 117m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (mtCO2e) every year since 2017 | Nature Geoscience

- “Intensified forest management efforts” in China from 2010 onwards have been linked to an acceleration in carbon absorption by plants and soils | Communications Earth and Environment

Recently published on WeChat

China Briefing is written by Anika Patel and edited by Simon Evans. Please send tips and feedback to china@carbonbrief.org

The post China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean energy’s share of economy | Record renewables | Thawing relations with UK appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Clean energy drove more than a third of China’s GDP growth in 2025

Solar power, electric vehicles (EVs) and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment.

Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) – comparable to the economies of Brazil or Canada.

The new analysis for Carbon Brief, based on official figures, industry data and analyst reports, shows that China’s clean-energy sectors nearly doubled in real value between 2022-25 and – if they were a country – would now be the 8th-largest economy in the world.

Other key findings from the analysis include:

- Without clean-energy sectors, China would have missed its target for GDP growth of “around 5%”, expanding by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%.

- Clean-energy industries are expanding much more quickly than China’s economy overall, with their annual growth rate accelerating from 12% in 2024 to 18% in 2025.

- The “new three” of EVs, batteries and solar continue to dominate the economic contribution of clean energy in China, generating two-thirds of the value added and attracting more than half of all investment in the sectors.

- China’s investments in clean energy reached 7.2tn yuan ($1.0tn) in 2025, roughly four times the still sizable $260bn put into fossil-fuel extraction and coal power.

- Exports of clean-energy technologies grew rapidly in 2025, but China’s domestic market still far exceeds the export market in value for Chinese firms.

These investments in clean-energy manufacturing represent a large bet on the energy transition in China and overseas, creating an incentive for the government and enterprises to keep the boom going.

However, there is uncertainty about what will happen this year and beyond, particularly for solar power, where growth has slowed in response to a new pricing system and where central government targets have been set far below the recent rate of expansion.

An ongoing slowdown could turn the sectors into a drag on GDP, while worsening industrial “overcapacity” and exacerbating trade tensions.

Yet, even if central government targets in the next five-year plan are modest, those from local governments and state-owned enterprises could still drive significant growth in clean energy.

This article updates analysis previously reported for 2023 and 2024.

Clean-energy sectors outperform wider economy

China’s clean-energy economy continues to grow far more quickly than the wider economy. This means that it is making an outsize contribution to annual economic growth.

The figure below shows that clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy overall in 2025 and more than 90% of the net rise in investment.

In 2022, China’s clean-energy economy was worth an estimated 8.4tn yuan ($1.2tn). By 2025, the sectors had nearly doubled in value to 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn).

This is comparable to the entire output of Brazil or Canada and positions the Chinese clean-energy industry as the 8th-largest economy in the world. Its value is roughly half the size of the economy of India – the world’s fourth largest – or of the US state of California.

The outperformance of the clean-energy sectors means that they are also claiming a rising share of China’s economy overall, as shown in the figure below.

This share has risen from 7.3% of China’s GDP in 2022 to 11.4% in 2025.

Without clean-energy sectors, China’s GDP would have expanded by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%, missing the target of “around 5%” growth by a wide margin.

Clean energy thus made a crucial contribution during a challenging year, when promoting economic growth was the foremost aim for policymakers.

The table below includes a detailed breakdown by sector and activity.

| Sector | Activity | Value in 2025, CNY bln | Value in 2025, USD bln | Year-on-year growth | Growth contribution | Value contribution | Value in 2025, CNY trn | Value in 2024, CNY trn | Value in 2023, CNY trn | Value in 2022, CNY trn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVs | Investment: manufacturing capacity | 1,643 | 228 | 18% | 10.4% | 10.7% | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| EVs | Investment: charging infrastructure | 192 | 27 | 58% | 2.9% | 1.2% | 0.192 | 0.122 | 0.1 | 0.08 |

| EVs | Production of vehicles | 3,940 | 548 | 29% | 36.4% | 25.6% | 3.94 | 3.065 | 2.26 | 1.65 |

| Batteries | Investment: battery manufacturing | 277 | 38 | 35% | 3.0% | 1.8% | 0.277 | 0.205 | 0.32 | 0.15 |

| Batteries | Exports: batteries | 724 | 101 | 51% | 10.1% | 4.7% | 0.724 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.34 |

| Solar power | Investment: power generation capacity | 1,182 | 164 | 15% | 6.3% | 7.7% | 1.182 | 1.031 | 0.808 | 0.34 |

| Solar power | Investment: manufacturing capacity | 506 | 70 | -23% | -6.5% | 3.3% | 0.506 | 0.662 | 0.95 | 0.51 |

| Solar power | Electricity generation | 491 | 68 | 33% | 5.1% | 3.2% | 0.491 | 0.369 | 0.26 | 0.19 |

| Solar power | Exports of components | 681 | 95 | 21% | 4.9% | 4.4% | 0.681 | 0.562 | 0.5 | 0.35 |

| Wind power | Investment: power generation capacity, onshore | 612 | 85 | 47% | 8.1% | 4.0% | 0.612 | 0.417 | 0.397 | 0.21 |

| Wind power | Investment: power generation capacity, offshore | 96 | 13 | 98% | 2.0% | 0.6% | 0.096 | 0.048 | 0.086 | 0.06 |

| Wind power | Electricity generation | 510 | 71 | 13% | 2.4% | 3.3% | 0.51 | 0.453 | 0.4 | 0.34 |

| Nuclear power | Investment: power generation capacity | 173 | 24 | 18% | 1.1% | 1.1% | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Nuclear power | Electricity generation | 216 | 30 | 8% | 0.7% | 1.4% | 0.216 | 0.2 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Hydropower | Investment: power generation capacity | 54 | 7 | -7% | -0.2% | 0.3% | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Hydropower | Electricity generation | 582 | 81 | 3% | 0.6% | 3.8% | 0.582 | 0.567 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

| Rail transportation | Investment | 902 | 125 | 6% | 2.1% | 5.8% | 0.902 | 0.851 | 0.764 | 0.714 |

| Rail transportation | Transport of passengers and goods | 1,020 | 142 | 3% | 1.3% | 6.6% | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.964 | 0.694 |

| Electricity transmission | Investment: transmission capacity | 644 | 90 | 6% | 1.5% | 4.2% | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.5 |

| Electricity transmission | Transmission of clean power | 52 | 7 | 14% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.052 | 0.046 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Energy storage | Investment: Pumped hydro | 53 | 7 | 5% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Energy storage | Investment: Grid-connected batteries | 232 | 32 | 52% | 3.3% | 1.5% | 0.232 | 0.152 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Energy storage | Investment: Electrolysers | 11 | 2 | 29% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0 | 0 |

| Energy efficiency | Revenue: Energy service companies | 620 | 86 | 17% | 3.8% | 4.0% | 0.62 | 0.528003 | 0.52 | 0.45 |

| Total | Investments | 7,198 | 1001 | 15% | 38.2% | 46.7% | 7.20 | 6.28 | 6.00 | 4.11 |

| Total | Production of goods and services | 8,216 | 1,143 | 22% | 61.8% | 53.3% | 8.22 | 6.73 | 5.58 | 4.32 |

| Total | Total GDP contribution | 15,414 | 2144 | 18% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 15.41 | 13.01 | 11.58 | 8.42 |

EVs and batteries were the largest drivers of GDP growth

In 2024, EVs and solar had been the largest growth drivers. In 2025, it was EVs and batteries, which delivered 44% of the economic impact and more than half of the growth of the clean-energy industries. This was due to strong growth in both output and investment.

The contribution to nominal GDP growth – unadjusted for inflation – was even larger, as EV prices held up year-on-year while the economy as a whole suffered from deflation. Investment in battery manufacturing rebounded after a fall in 2024.

The major contribution of EVs and batteries is illustrated in the figure below, which shows both the overall size of the clean-energy economy and the sectors that added the most to the rise from year to year.

The next largest subsector was clean-power generation, transmission and storage, which made up 40% of the contribution to GDP and 30% of the growth in 2025.

Within the electricity sector, the largest drivers were growth in investment in wind and solar power generation capacity, along with growth in power output from solar and wind, followed by the exports of solar-power equipment and materials.

Investment in solar-panel supply chains, a major growth driver in 2022-23, continued to fall for the second year. This was in line with the government’s efforts to rein in overcapacity and “irrational” price competition in the sector.

Finally, rail transportation was responsible for 12% of the total economic output of the clean-energy sectors, but saw relatively muted growth year-on-year, with revenue up 3% and investment by 6%.

Note that the International Energy Agency (IEA) world energy investment report projected that China invested $627bn in clean energy in 2025, against $257bn in fossil fuels.

For the same sectors as the IEA report, this analysis puts the value of clean-energy investment in 2025 at a significantly more conservative $430bn. The higher figures in this analysis overall are therefore the result of wider sectoral coverage.

Electric vehicles and batteries

EVs and vehicle batteries were again the largest contributors to China’s clean-energy economy in 2025, making up an estimated 44% of value overall.

Of this total, the largest share of both total value and growth came from the production of battery EVs and plug-in hybrids, which expanded 29% year-on-year. This was followed by investment into EV manufacturing, which grew 18%, after slower growth rates in 2024.

Investment in battery manufacturing also rebounded after a drop in 2024, driven by new battery technology and strong demand from both domestic and international markets. Battery manufacturing investment grew by 35% year-on-year to 277bn yuan.

The share of electric vehicles (EVs) will have reached 12% of all vehicles on the road by the end of 2025, up from 9% a year earlier and less than 2% just five years ago.

The share of EVs in the sales of all new vehicles increased to 48%, from 41% in 2024, with passenger cars crossing the 50% threshold. In November, EV sales crossed the 60% mark in total sales and they continue to drive overall automotive sales growth, as shown below.

Electric trucks experienced a breakthrough as their market share rose from 8% in the first nine months of 2024 to 23% in the same period in 2025.

Policy support for EVs continues, for example, with a new policy aiming to nearly double charging infrastructure in the next three years.

Exports grew even faster than the domestic market, but the vast majority of EVs continue to be sold domestically. In 2025, China produced 16.6m EVs, rising 29% year-on-year. While exports accounted for only 21% or 3.4m EVs, they grew by 86% year-on-year. Top export destinations for Chinese EVs were western Europe, the Middle East and Latin America.

The value of batteries exported also grew rapidly by 41% year-on-year, becoming the third largest growth driver of the GDP. Battery exports largely went to western Europe, north America and south-east Asia.

In contrast with deflationary trends in the price of many clean-energy technologies, average EV prices have held up in 2025, with a slight increase in average price of new models, after discounts. This also means that the contribution of the EV industry to nominal GDP growth was even more significant, given that overall producer prices across the economy fell by 2.6%. Battery prices continued to drop.

Clean-power generation

The solar power sector generated 19% of the total value of the clean-energy industries in 2025, adding 2.9tn yuan ($41bn) to the national economy.

Within this, investment in new solar power plants, at 1.2tn yuan ($160bn), was the largest driver, followed by the value of solar technology exports and by the value of the power generated from solar. Investment in manufacturing continued to fall after the wave of capacity additions in 2023, reaching 0.5tn yuan ($72bn), down 23% year-on-year.

In 2025, China achieved another new record of wind and solar capacity additions. The country installed a total of 315GW solar and 119GW wind capacity, adding more solar and two times as much wind as the rest of the world combined.

Clean energy accounted for 90% of investment in power generation, with solar alone covering 50% of that. As a result, non-fossil power made up 42% of total power generation, up from 39% in 2024.

However, a new pricing policy for new solar and wind projects and modest targets for capacity growth have created uncertainty about whether the boom will continue.

Under the new policy, new clean-power generation has to compete on price against existing coal power in markets that place it at a disadvantage in some key ways.

At the same time, the electricity markets themselves are still being introduced and developed, creating investment uncertainty.

Investment in solar power generation increased year-on-year by 15%, but experienced a strong stop-and-go cycle. Developers rushed to finish projects ahead of the new pricing policy coming into force in June and then again towards the end of the year to finalise projects ahead of the end of the current 14th five-year plan.

Investment in the solar sector as a whole was stable year-on-year, with the decline in manufacturing capacity investment balanced by continued growth in power generation capacity additions. This helped shore up the utilisation of manufacturing plants, in line with the government’s aim to reduce “disorderly” price competition.

By late 2025, China’s solar manufacturing capacity reached an estimated 1,200GW per year, well ahead of the global capacity additions of around 650GW in 2025. Manufacturers can now produce far more solar panels than the global market can absorb, with fierce competition leading to historically low profitability.

China’s policymakers have sought to address the issue since mid-2024, warning against “involution”, passing regulations and convening a sector-wide meeting to put pressure on the industry. This is starting to yield results, with losses narrowing in the third quarter of 2025.

The volume of exports of solar panels and components reached a record high in 2025, growing 19% year-on-year. In particular, exports of cells and wafers increased rapidly by 94% and 52%, while panel exports grew only by 4%.

This reflects the growing diversification of solar-supply chains in the face of tariffs and with more countries around the world building out solar panel manufacturing capacity. The nominal value of exports fell 8%, however, due to a fall in average prices and a shift to exporting upstream intermediate products instead of finished panels.

Hydropower, wind and nuclear were responsible for 15% of the total value of the clean-energy sectors in 2025, adding some 2.2tn yuan ($310bn) to China’s GDP in 2025.

Nearly two-thirds of this (1.3tn yuan, $180bn) came from the value of power generation from hydropower, wind and nuclear, with investment in new power generation projects contributing the rest.

Power generation grew 33% from solar, 13% from wind, 3% from hydropower and 8% from nuclear.

Within power generation investment, solar remained the largest segment by value – as shown in the figure below – but wind-power generation projects were the largest contributor to growth, overtaking solar for the first time since 2020.

In particular, offshore wind power capacity investment rebounded as expected, doubling in 2025 after a sharp drop in 2024.

Investment in nuclear projects continued to grow but remains smaller in total terms, at 17bn yuan. Investment in conventional hydropower continued to decline by 7%.

Electricity storage and grids

Electricity transmission and storage were responsible for 6% of the total value of the clean-energy sectors in 2025, accounting for 1.0 tn yuan ($140bn).

The most valuable sub-segment was investment in power grids, growing 6% in 2025 and reaching $90bn. This was followed by investment in energy storage, including pumped hydropower, grid-connected battery storage and hydrogen production.

Investment in grid-connected batteries saw the largest year-on-year growth, increasing by 50%, while investments in electrolysers also grew by 30%. The transmission of clean power increased an estimated 13%, due to rapid growth in clean-power generation.

China’s total electricity storage capacity reached more than 213GW, with battery storage capacity crossing 145GW and pumped hydro storage at 69GW. Some 66GW of battery storage capacity was added in 2025, up 52% year-on-year and accounting for more than 40% of global capacity additions.

Notably, capacity additions accelerated in the second half of the year, with 43GW added, compared with the first half, which saw 23GW of new capacity.

The battery storage market initially slowed after the renewable power pricing policy, which banned storage mandates after May, but this was quickly replaced by a “market-driven boom”. Provincial electricity spot markets, time-of-day tariffs and increasing curtailment of solar power all improved the economics of adding storage.

By the end of 2025, China’s top five solar manufacturers had all entered the battery storage market, making a shift in industry strategy.

Investment in pumped hydropower continued to increase, with 15GW of new capacity permitted in the first half of 2025 alone and 3GW entering operation.

Railways

Rail transportation made up 12% of the GDP contribution of the clean-energy sectors, with revenue from passenger and goods rail transportation the largest source of value. Most growth came from investment in rail infrastructure, which increased 6% year-on-year

The electrification of transport is not limited to EVs, as rail passenger, freight and investment volumes saw continued growth. The total length of China’s high-speed railway network reached 50,000km in 2025, making up more than 70% of the global high-speed total.

Energy efficiency

Investment in energy efficiency rebounded strongly in 2025. Measured by the aggregate turnover of large energy service companies (ESCOs), the market expanded by 17% year-on-year, returning to growth rates last seen during 2016-2020.

Total industry turnover has also recovered to its previous peak in 2021, signalling a clear turnaround after three years of weakness.

Industry projections now anticipate annual turnover reaching 1tn yuan in annual turnover by 2030, a target that had previously been expected to be met by 2025.

China’s ESCO market has evolved into the world’s largest. Investment within China’s ESCO market remains heavily concentrated in the buildings sector, which accounts for around 50% of total activity. Industrial applications make up a further 21%, while energy supply, demand-side flexibility and energy storage together account for approximately 16%.

Implications of China’s clean-energy bet

Ongoing investment of hundreds of billions of dollars into clean-energy manufacturing represents a gigantic economic and financial bet on a continuing global energy transition.

In addition to the domestic investment covered in this article, Chinese firms are making major investments in overseas manufacturing.

The clean-energy industries have played a crucial role in meeting China’s economic targets during the five-year period ending this year, delivering an estimated 40%, 25% and 37% of all GDP growth in 2023, 2024 and 2025, respectively.

However, the developments next year and beyond are unclear, particularly for solar power generation, with the new pricing system for renewable power generation leading to a short-term slowdown and creating major uncertainty, while central government targets have been set far below current rates of clean-electricity additions.

Investment in solar-power generation and solar manufacturing declined in the second half of the year, while investment in generation clocked growth for the full year, showing the risk to the industries under the current power market set-ups that favour coal-fired power.

The reduction in the prices of clean-energy technology has been so dramatic that when the prices for GDP statistics are updated, the sectors’ contribution to real GDP – adjusted for inflation or, in this case deflation – will be revised down.

Nevertheless, the key economic role of the industry creates a strong motivation to keep the clean-energy boom going. A slowdown in the domestic market could also undermine efforts to stem overcapacity and inflame trade tensions by increasing pressure on exports to absorb supply.

A recent CREA survey of experts working on climate and energy issues in China found that the majority believe that economic and geopolitical challenges will make the “dual carbon” goals – and with that, clean-energy industries – only more important.

Local governments and state-owned enterprises will also influence the outlook for the sector. Their previous five-year plans played a key role in creating the gigantic wind and solar power “bases” that substantially exceeded the central government’s level of ambition.

Provincial governments also have a lot of leeway in implementing the new electricity markets and contracting systems for renewable power generation. The new five-year plans, to be published this year, will therefore be of major importance.

About the data

Reported investment expenditure and sales revenue has been used where available. When this is not available, estimates are based on physical volumes – gigawatts of capacity installed, number of vehicles sold – and unit costs or prices.

The contribution to real growth is tracked by adjusting for inflation using 2022-2023 prices.

All calculations and data sources are given in a worksheet.

Estimates include the contribution of clean-energy technologies to the demand for upstream inputs such as metals and chemicals.

This approach shows the contribution of the clean-energy sectors to driving economic activity, also outside the sectors themselves, and is appropriate for estimating how much lower economic growth would have been without growth in these sectors.

Double counting is avoided by only including non-overlapping points in value chains. For example, the value of EV production and investment in battery storage of electricity is included, but not the value of battery production for the domestic market, which is predominantly an input to these activities.

Similarly, the value of solar panels produced for the domestic market is not included, as it makes up a part of the value of solar power generating capacity installed in China. However, the value of solar panel and battery exports is included.

In 2025, there was a major divergence between two different measures of investment. The first, fixed asset investment, reportedly fell by 3.8%, the first drop in 35 years. In contrast, gross capital formation saw the slowest growth in that period but still inched up by 2%.

This analysis uses gross capital formation as the measure of investment, as it is the data point used for GDP accounting. However, the analysis is unable to account for changes in inventories, so the estimate of clean-energy investment is for fixed asset investment in the sectors.

The analysis does not explicitly account for the small and declining role of imports in producing clean-energy goods and services. This means that the results slightly overstate the contribution to GDP but understate the contribution to growth.

For example, one of the most important import dependencies that China has is for advanced computing chips for EVs. The value of the chips in a typical EV is $1,000 and China’s import dependency for these chips is 90%, which suggests that imported chips represent less than 3% of the value of EV production.

The estimates are likely to be conservative in some key respects. For example, Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates “investment in the energy transition” in China in 2024 at $800bn. This estimate covers a nearly identical list of sectors to ours, but excludes manufacturing – the comparable number from our data is $600bn.

China’s National Bureau of Statistics says that the total value generated by automobile production and sales in 2023 was 11tn yuan. The estimate in this analysis for the value of EV sales in 2023 is 2.3tn yuan, or 20% of the total value of the industry, when EVs already made up 31% of vehicle production and the average selling prices for EVs was slightly higher than for internal combustion engine vehicles.

The post Analysis: Clean energy drove more than a third of China’s GDP growth in 2025 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Clean energy drove more than a third of China’s GDP growth in 2025

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility