Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil fuels and cement will rise around 0.8% in 2024, reaching a record 37.4bn tonnes of CO2 (GtCO2), according to the 2024 Global Carbon Budget report by the Global Carbon Project.

This is 0.4GtCO2 higher than the previous record, set in 2023.

Total CO2 emissions – including both fossil and land-use emissions – will also set a new record at 41.6GtCO2, reflecting a growth of 2% over 2023 levels.

This is due, in part, to higher than usual land-use emissions driven by extreme wildfire activity in South America.

Despite the increase in 2024, total CO2 emissions have largely plateaued over the past decade, a sign that the world is making some modest progress tackling emissions.

But a flattening of emissions is far from what is needed to bring global emissions down to zero and stabilise global temperatures in-line with Paris Agreement goals.

The 19th edition of the Global Carbon Budget, which is published today, also reveals:

- Emissions emissions are projected to decrease significantly in the EU (down 3.8%) and slightly in the US (down 0.6%) in 2024. They are expected to increase slightly in China (up 0.2%), and increase significantly in India (up 4.6%) and the rest of the world (up 1.6%, including international shipping and aviation).

- Global emissions from coal increased by 0.2% in 2024 compared to 2023, while oil emissions increased 0.9% and gas emissions increased by 2.4%. Emissions from cement and other sources fell by 2.8%.

- Global land-use emissions clocked in at 4.2GtCO2 in 2024. This represents a 0.5GtCO2 increase over 2023 and was primarily driven by wildfire emissions linked to deforestation and forest degradation in South America. Overall, land-use emissions have decreased by around 28% since their peak in the late-1990s, with a particularly large drop in the past decade.

- While the land sink was quite weak in 2023 – leading to speculation that it may be on a path toward collapse – it appears to have largely recovered back to close to its average for the past decade.

- If global emissions remain at current levels, the remaining carbon budget to limit warming to 1.5C (with a 50% chance) will be exhausted in the next six years. Carbon budgets to limit warming to 1.7C and 2C would similarly be used up in 15 and 27 years, respectively.

- The concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere is set to reach 422.5 parts per million (ppm) in 2024, 2.8ppm above 2023 and 52% above pre-industrial levels.

Both global fossil and total CO2 emissions at record levels

The 2024 Global Carbon Budget finds that CO2 emissions from fossil use are projected to rise 0.8% in 2024, reaching a record 37.4GtCO2 – 0.4GtCO2 higher than the previous record, set last year.

Total CO2 emissions, which include land-use change, are also expected to reach record highs at 41.6GtCO2, or 2.0% above the previous record set in 2023.

This large increase was driven both by consistent growth in fossil-fuel emissions and abnormally high land-use emissions in 2024 – due in part to wildfires in South America exacerbated by a strong El Niño event and high temperatures.

Each year the Global Carbon Budget is updated to include the latest data as well as improvements to modelling sources and sinks, resulting in some year-to-year revisions to the historical record.

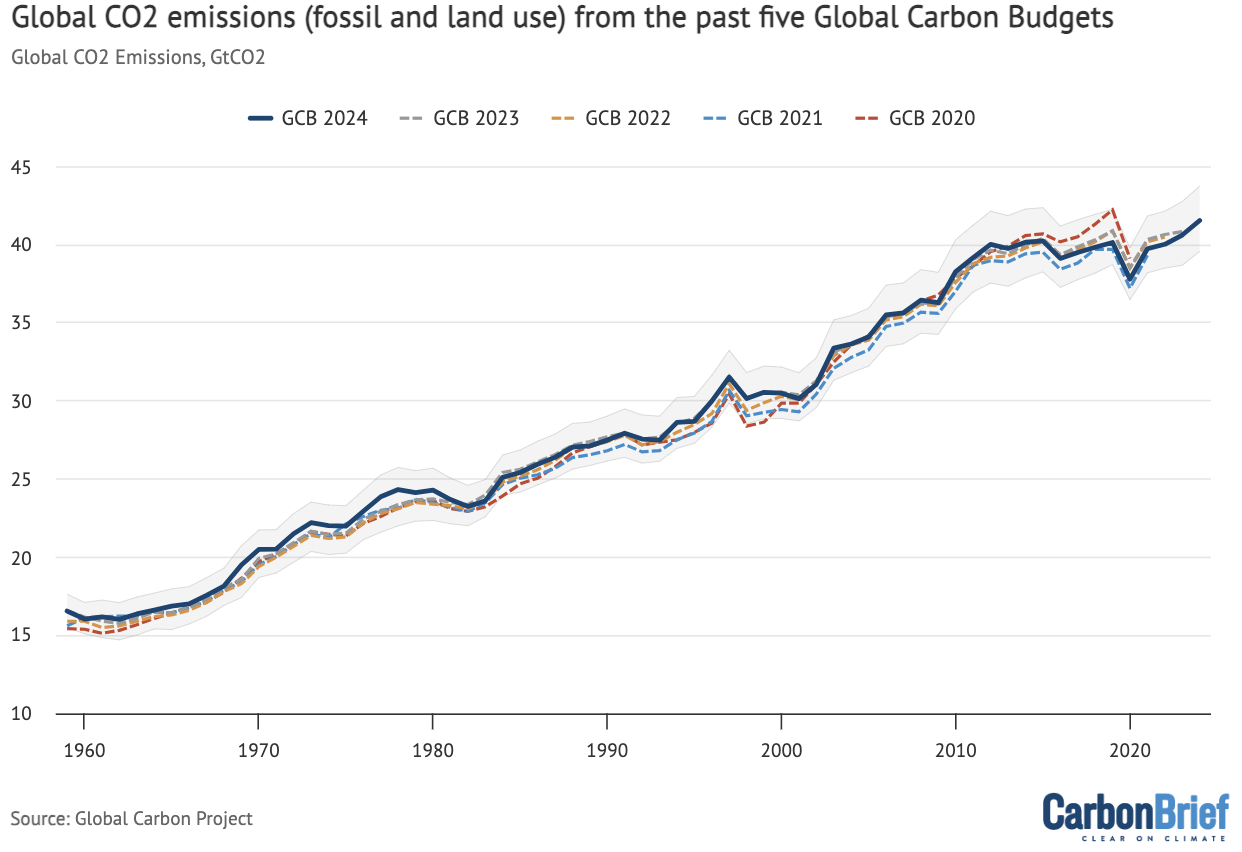

The figure below shows the 2024 global CO2 emissions update (dark blue solid line) alongside 2023 (grey dotted) 2022 (yellow dotted), 2021 (bright blue dotted) and 2020 (red dotted). The shaded area indicates the uncertainty around the new 2024 budget.

The 2024 figures are generally quite similar to those in the 2023 Global Carbon Budget, though they show somewhat higher emissions prior to 1980 and slightly lower emissions over the past seven years. Revisions to the data mean that 2023 is no longer a hair below 2019 levels, as was reported by Carbon Brief last year, but rather exceeds them by nearly 0.5GtCO2.

Annual total global CO2 emissions – from fossil and land-use change – between 1959 and 2024 for the 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024 versions of the Global Carbon Project’s Global Carbon Budget, in billions of tonnes of CO2 per year (GtCO2). Shaded area shows the estimated one-sigma uncertainty for the 2024 budget. Data from the Global Carbon Project; chart by Carbon Brief.

Total global CO2 emissions have notably plateaued in the past decade (2015-24), growing at only 0.2% per year compared to the 1.9% rate of growth over the previous decade (2005-214) and the longer-term average growth rate of 1.7% between 1959 and 2014.

This apparent flattening is due to declining land-use emissions compensating for continued increases in fossil CO2 emissions. Fossil emissions grew around 0.2GtCO2 per year over the past decade, while land-use emissions decreased by a comparable amount.

However, despite the emissions plateau, there is still no sign of the rapid and deep decrease in CO2 emissions needed to reach net-zero and stabilise global temperatures in-line with Paris Agreement goals.

If global emissions remain at current levels, the remaining carbon budget to limit warming to 1.5C (with a 50% chance) will be exhausted in the next six years. Carbon budgets to limit warming to 1.7C and 2C would similarly be used up in 15 and 27 years, respectively.

Global fossil CO2 emissions also grew more slowly in the past decade (0.7% per year) compared to the previous decade (2.1%). This was driven by the continued decarbonisation of energy systems – including a shift from burning coal to gas and replacing fossil fuels with renewables – as well as slightly weaker global economic growth during the past decade.

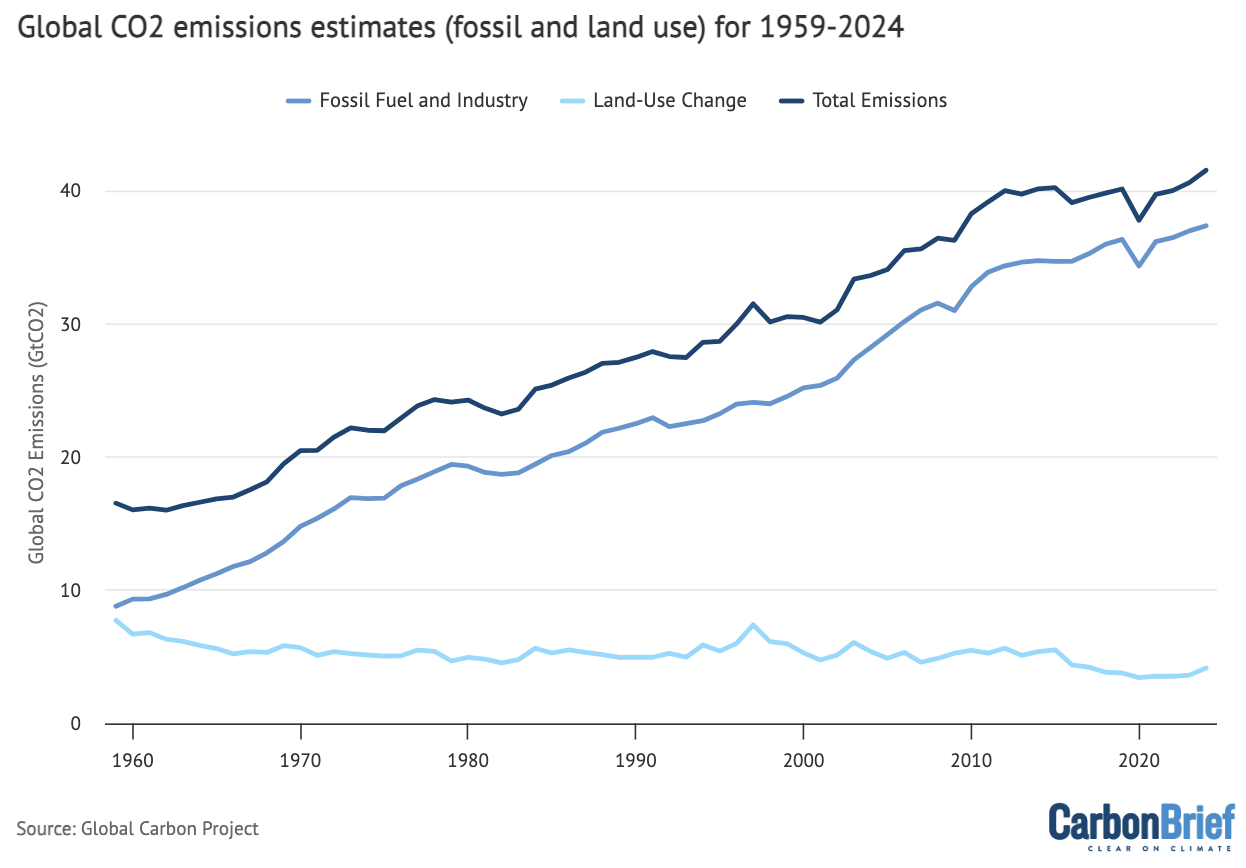

The figure below breaks down global emissions (dark blue line) in the 2024 budget into fossil (mid blue) and land-use (light blue) components. Fossil CO2 emissions represent the bulk of total global emissions in recent years, accounting for approximately 90% of emissions in 2024 (compared to 10% for land use). This represents a large change from the first half of the 20th century, when land-use emissions were approximately the same as fossil emissions.

Global fossil emissions include CO2 emitted from burning coal, oil and gas, as well as the production of cement. However, the Global Carbon Budget also subtracts the cement carbonation sink – CO2 slowly absorbed by cement once it is exposed to the air – from fossil emissions in each year to determine total fossil emissions.

Global CO2 emissions separated out into fossil and land-use change components between 1959 and 2024 from the 2024 Global Carbon Budget. Note that fossil CO2 emissions are inclusive of the cement carbonation sink. Data from the Global Carbon Project; chart by Carbon Brief.

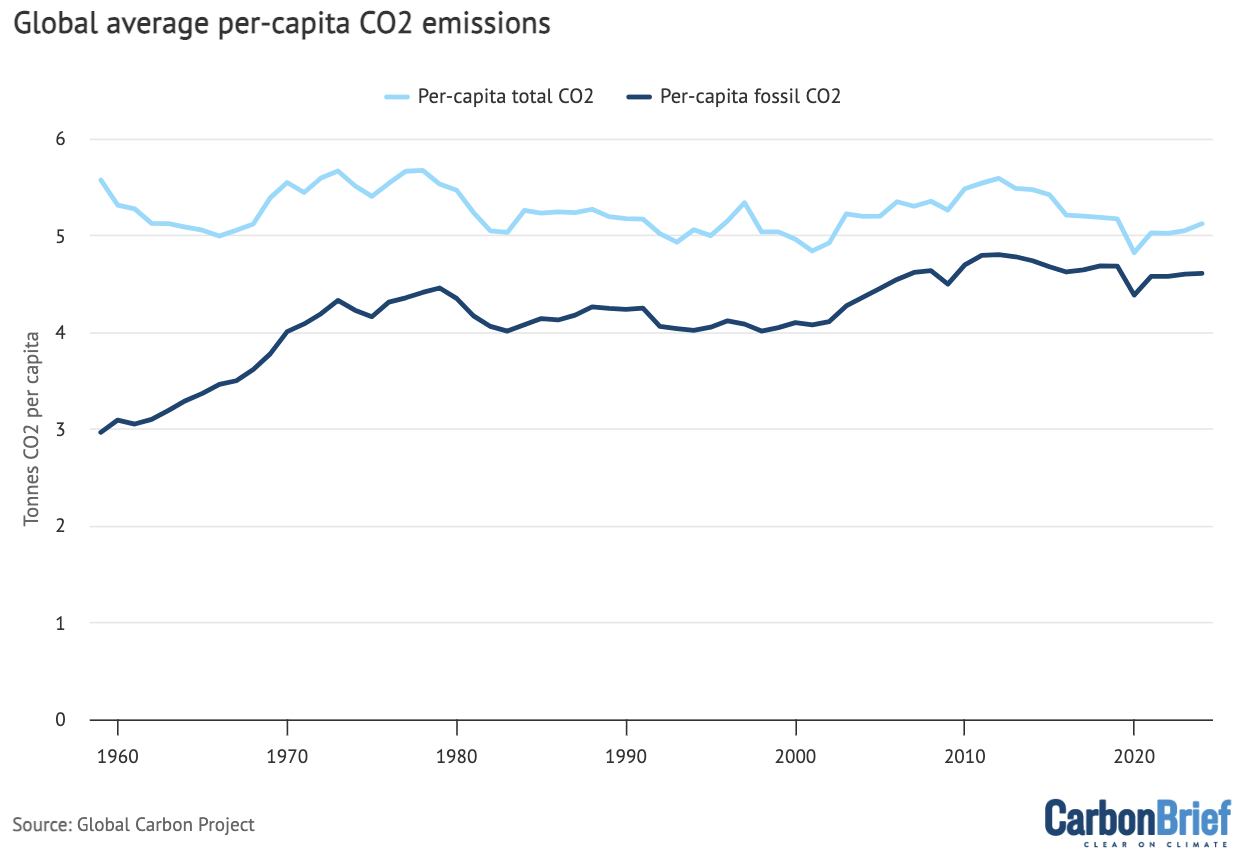

Global emissions can also be expressed on a per-capita basis, as shown in the figure below. While it is ultimately total global emissions that matter for the Earth’s climate – and a global per-capita figure glosses over a lot of variation among and within countries it is noteworthy that global per-capita emissions peaked in 2012 and have been slightly declining in the years since.

Global per-capita CO2 emissions between 1959 and 2024. Note that fossil CO2 emissions are inclusive of the cement carbonation sink. Data from the Global Carbon Project; chart by Carbon Brief.

Land-use emissions trending downward

Global land-use emissions stem from deforestation, degradation, loss of peatlands and harvesting trees for wood. They averaged 4GtCO2 over the past decade (2015-24) and the Global Carbon Budget provides an initial projection for 2024 of 4.2GtCO2.

This represents a 0.5GtCO2 increase over land-use emissions in 2023. This was primarily driven by wildfire emissions linked to deforestation and forest degradation in South America. Drought conditions associated with this year’s El Niño event contributed to the severity of the fires.

Overall, land-use emissions have decreased by around 28% since their peak in the late-1990s, with a particularly large drop in the past decade.

This decline is statistically significant and is due both to decreasing deforestation and increasing levels of reforestation and afforestation globally (though rates of reforestation and afforestation have largely stagnated over the past decade).

This year’s Global Carbon Budget features a number of important improvements to land-use change emissions estimates, including updated estimates of cropland and pasture area in major countries.

Four countries – Brazil, Indonesia, China and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) – collectively contribute approximately 60% of the global land-use emissions.

The figure below shows changes in emissions over time in these countries, as well as land-use emissions in the rest of the world (grey). Note that Chinese land-use emissions are negative in recent years.

Annual CO2 emissions from land-use change by major emitting countries and the rest of world over 1959-2023. Note that country-level land-use change emissions are not yet available for 2024. Data from the Global Carbon Project; chart by Carbon Brief.

Fossil CO2 in major emitting countries

Global emissions of fossil CO2 – including coal, oil, gas and cement – increased by around 0.8% in 2024, relative to 2023, with an uncertainty range of -0.3% to 1.9%. This represents a new record high and is 2.6% above the 2019 pre-Covid levels.

The figure below shows global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels, divided into emissions from major emitting countries including China (dark blue shading), India (mid blue), the US (light blue), EU (pale blue) and the remainder of the world (grey).

Annual fossil CO2 emissions by major countries and the rest of the world over 1959-2024, excluding the cement carbonation sink as national-level values are not available. Data from the Global Carbon Project; chart by Carbon Brief.

For this year, China represents 32% of global CO2 emissions. Their emissions in 2024 are projected to increase by a relatively small 0.2% (with an uncertainty range of -1.6% to +2%), driven by a small rise in emissions from coal (0.3%) and a large rise in natural gas emissions (8%). Emissions from oil are expected to decrease modestly (-0.8%), while emissions from cement are expected to fall sharply (-8.1%).

The Global Carbon Budget report suggests that Chinese oil emissions have probably already peaked, reflecting the acceleration of vehicle electrification.

India represents 8% of global emissions. In 2024, Indian emissions are projected to increase by 4.6% (with a range from 3.0% to 6.1%), with a 4.5% increase in emissions from coal, a 3.6% increase in emissions from oil, a 11.8% increase in emissions from natural gas and a 4% increase in emissions from cement.

While renewable energy is expanding quickly in India, it remains far slower than the rate of power demand growth as the economy rapidly expands.

The US represents 13% of global emissions this year – though is responsible for a much larger portion of historical emissions and associated atmospheric accumulation of CO2.

US emissions are projected to decrease by 0.6% in 2024 (ranging from -2.9% to +1.7%). This is being driven by a modest decrease in coal emissions (falling 3.5%). Oil emissions are expected to decline by a slight 0.7%, reflecting the rise of electric vehicles, while emissions from gas are expected to increase by 1%.

The EU represents 7% of global emissions. EU emissions are expected to decrease by 3.8% in 2024, driven by a 15.8% decline in coal emissions, a 1.3% decline in natural gas emissions, and a 3.5% decline in cement emissions. EU oil emissions are expected to increase slightly, by 0.2%.

The EU’s overall emissions decline is being driven by a combination of rapid clean energy adoption as well as relatively weak economic growth and high energy prices.

International aviation and shipping (included in the “rest of world” in the figure above) are responsible for 3% of global emissions. They are projected to increase by

7.8% in 2024, but remain below their 2019 pre-pandemic level by 3.5%.

The rest of the world (excluding aviation) represents 38% of global emissions. Emissions are expected to grow by 1.1% in 2024 (ranging from -1.0% to +3.3%), with increases in emissions from coal (0.5%), oil (0.5%), natural gas (2.2%) and cement (2%).

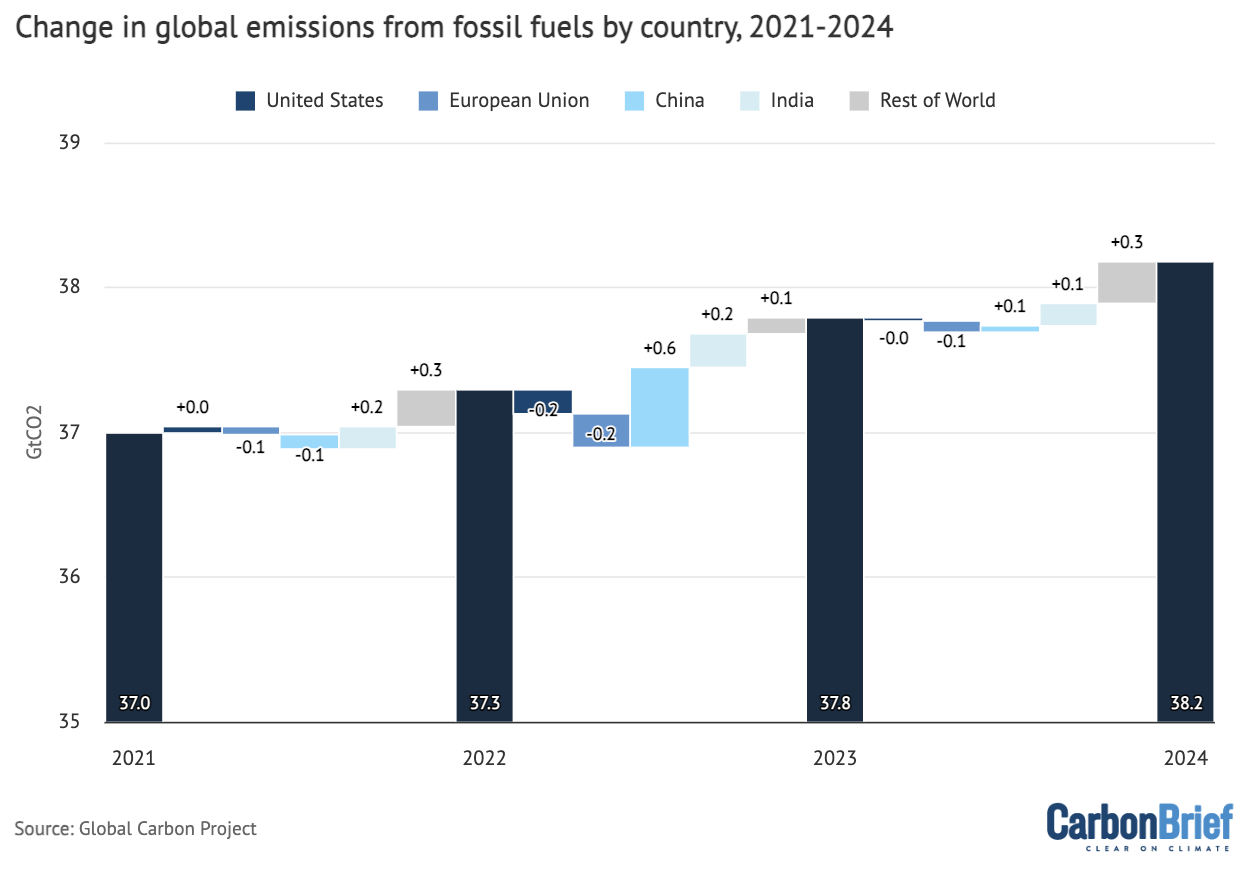

Overall, emissions are projected to decrease in the EU and US in 2024, increase slightly in China, and increase significantly in India and the rest of the world.

The total emissions for each year between 2021 and 2024, as well as the countries and regions that were responsible for the changes in absolute emissions, are shown in the figure below.

Annual emissions for 2021, 2022, 2023 and estimates for 2024 are shown by the navy blue bars. The smaller bars show the change in emissions between each set of years, broken down by country or region – the US (dark blue), EU (mid blue), China (light blue), India (pale blue) and the rest of the world (grey). Negative values show reductions in emissions, while positive values reflect emission increases.

Annual global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels (navy blue bars) and drivers of changes between years by country (smaller bars), excluding the cement carbonation sink as national-level values are not available. Negative values indicate reductions in emissions. Note that the y-axis does not start at zero. Data from the Global Carbon Project; chart by Carbon Brief.

The Global Carbon Project notes that emissions have declined over the past decade (2014-23) in 22 nations – up from 18 countries during the decade prior to that (2004-13). This decrease comes despite continued domestic economic growth and represents a long-term decoupling of CO2 emissions and the economy.

CO2 emissions decreased in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries by 1.4% per year over the past decade, compared to a decrease of 0.9% per year in the decade prior. Non-OECD countries saw their emissions grow more slowly (1.8%) over the last decade than the prior one (4.9%).

Growth in emissions from coal, oil, and gas

Global fossil-fuel emissions primarily result from the combustion of coal, oil and natural gas. Coal is responsible for more emissions than any other fossil fuel, representing approximately 41% of global fossil CO2 emissions in 2024. Oil is the second largest contributor at 33% of fossil CO2, while gas rounds out the pack at 22%.

These percentages reflect both the amount of each fossil fuel consumed globally, but also differences in CO2 intensities. Coal results in the most CO2 emitted per unit of heat or energy produced, followed by oil and natural gas.

The figure below shows global CO2 emissions from different fuels over time, covering coal (dark blue shading), oil (mid blue) and gas (light blue), as well as cement production (pale blue) and other sources (grey).

While coal emissions increased rapidly in the mid-2000s, it has largely plateaued since 2013. However, coal use increased significantly in 2021 and then slightly in the subsequent three years.

Annual CO2 emissions by fossil fuel over 1959-2024, excluding the cement carbonation sink. Data from the Global Carbon Project; chart by Carbon Brief.

Global emissions from coal increased by 0.2% in 2024 compared to 2023, while oil emissions increased 0.9% and gas emissions increased by 2.4%. Emissions from cement and other sources fell by 3%.

Despite setting a new record this year, global coal use is only 3% above 2013 levels – a full 12 years ago. By contrast, during the 2000s, global coal use grew at a rate of around 4% every single year.

The total emissions for each year between 2021 and 2024 (navy blue bars), as well as the absolute change in emissions for each fuel between years, are shown in the figure below.

Annual global CO2 emissions from fossil fuels (navy blue bars) and drivers of changes between years by fuel, excluding the cement carbonation sink. Negative values indicate reductions in emissions. Note that the y-axis does not start at zero. Data from the Global Carbon Project; chart by Carbon Brief.

Even though they have been increasing over the past four years, global CO2 emissions from oil remain very slightly (0.8%) below the pre-pandemic highs of 2019.

The global carbon budget

Every year, the Global Carbon Project provides an estimate of the overall “global carbon budget”. This is based on estimates of the release of CO2 through human activity and its uptake by the oceans and land, with the remainder adding to atmospheric concentrations of the gas.

(This differs from the commonly used term “remaining carbon budget”, which refers to the amount of CO2 that can be released while keeping warming below global limits of 1.5 or 2C.)

The most recent budget, including estimated values for 2024, is shown in the figure below. Values above zero represent sources of CO2 – from fossil fuels and industry (dark blue shading) and land use (mid blue) – while values below zero represent “carbon sinks” that remove CO2 from the atmosphere. Any CO2 emissions that are not absorbed by the oceans (light grey) or land vegetation (mid grey) accumulate in the atmosphere (dark grey).

Annual global carbon budget of sources and sinks over 1959-2024. Fossil CO2 emissions include the cement carbonation sink. Note that the budget does not fully balance every year due to remaining uncertainties, particularly in sinks. Data from the Global Carbon Project; chart by Carbon Brief.

Over the past decade (2015-24), the world’s oceans have taken up approximately 26.5% of total human emissions, or around 10.6GtCO2 per year. The ocean CO2 sink has been relatively flat since 2016 after growing rapidly over the prior decades, reflecting the plateauing of global emissions during that period.

The land sink takes up around 29% of global emissions, or 11.5GtCO2 per year on average. While the land sink was quite weak in 2023 – leading some to speculate that it may be on a path toward collapse – it appears to have largely recovered back to close to its average level over the past decade in 2024 as El Niño conditions have faded.

Global CO2 emissions from fires were quite high in 2024, around 7GtCO2 over the first 10 months of the year and similar to the above average values in 2023.

This was driven by large emissions in North and South America, particularly in Canada and Brazil. (It is not possible to make a direct comparison between reported fire CO2 emissions and other components of the global carbon budget as they already show up in both parts of the land sink and land-use emissions.)

Overall, the impact of the ongoing emissions from human activity is that atmospheric CO2 continues to increase.

The growth rate of atmospheric CO2 in 2024 is expected to be around 2.76ppm, which is above average compared to the rate of 2.46% over the past decade (2014-23).

The 2024 rise in atmospheric CO2 concentration was the fifth largest over the 1959-2024 period, closely following 2023, 2015, 2016 and 1998 – most of which were strong El Niño years.

Atmospheric CO2 concentrations are set to reach an annual average of 422.5ppm in 2024, representing an increase of 52% above pre-industrial levels of 280ppm.

The post Analysis: Global CO2 emissions will reach new high in 2024 despite slower growth appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Global CO2 emissions will reach new high in 2024 despite slower growth

Climate Change

Hurricane Helene Is Headed for Georgians’ Electric Bills

A new storm recovery charge could soon hit Georgia Power customers’ bills, as climate change drives more destructive weather across the state.

Hurricane Helene may be long over, but its costs are poised to land on Georgians’ electricity bills. After the storm killed 37 people in Georgia and caused billions in damage in September 2024, Georgia Power is seeking permission from state regulators to pass recovery costs on to customers.

Climate Change

Amid Affordability Crisis, New Jersey Hands $250 Million Tax Break to Data Center

Gov. Mikie Sherrill says she supports both AI and lowering her constituents’ bills.

With New Jersey’s cost-of-living “crisis” at the center of Gov. Mikie Sherrill’s agenda, her administration has inherited a program that approved a $250 million tax break for an artificial intelligence data center.

Amid Affordability Crisis, New Jersey Hands $250 Million Tax Break to Data Center

Climate Change

Curbing methane is the fastest way to slow warming – but we’re off the pace

Gabrielle Dreyfus is chief scientist at the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development, Thomas Röckmann is a professor of atmospheric physics and chemistry at Utrecht University, and Lena Höglund Isaksson is a senior research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

This March scientists and policy makers will gather near the site in Italy where methane was first identified 250 years ago to share the latest science on methane and the policy and technology steps needed to rapidly cut methane emissions. The timing is apt.

As new tools transform our understanding of methane emissions and their sources, the evidence they reveal points to a single conclusion: Human-caused methane emissions are still rising, and global action remains far too slow.

This is the central finding of the latest Global Methane Status Report. Four years into the Global Methane Pledge, which aims for a 30% cut in global emissions by 2030, the good news is that the pledge has increased mitigation ambition under national plans, which, if fully implemented, could result in the largest and most sustained decline in methane emissions since the Industrial Revolution.

The bad news is this is still short of the 30% target. The decisive question is whether governments will move quickly enough to turn that bend into the steep decline required to pump the brake on global warming.

What the data really show

Assessing progress requires comparing three benchmarks: the level of emissions today relative to 2020, the trajectory projected in 2021 before methane received significant policy focus, and the level required by 2030 to meet the pledge.

The latest data show that global methane emissions in 2025 are higher than in 2020 but not as high as previously expected. In 2021, emissions were projected to rise by about 9% between 2020 and 2030. Updated analysis places that increase closer to 5%. This change is driven by factors such as slower than expected growth in unconventional gas production between 2020 and 2024 and lower than expected waste emissions in several regions.

Gas flaring soars in Niger Delta post-Shell, afflicting communities

This updated trajectory still does not deliver the reductions required, but it does indicate that the curve is beginning to bend. More importantly, the commitments already outlined in countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions and Methane Action Plans would, if fully implemented, produce an 8% reduction in global methane emissions between 2020 and 2030. This would turn the current increase into a sustained decline. While still insufficient to reach the Global Methane Pledge target of a 30% cut, it would represent historical progress.

Solutions are known and ready

Scientific assessments consistently show that the technical potential to meet the pledge exists. The gap lies not in technology, but in implementation.

The energy sector accounts for approximately 70% of total technical methane reduction potential between 2020 and 2030. Proven measures include recovering associated petroleum gas in oil production, regular leak detection and repair across oil and gas supply chains, and installing ventilation air oxidation technologies in underground coal mines. Many of these options are low cost or profitable. Yet current commitments would achieve only one third of the maximum technically feasible reductions in this sector.

Recent COP hosts Brazil and Azerbaijan linked to “super-emitting” methane plumes

Agriculture and waste also provide opportunities. Rice emissions can be reduced through improved water management, low-emission hybrids and soil amendments. While innovations in technology and practices hold promise in the longer term, near-term potential in livestock is more constrained and trends in global diets may counteract gains.

Waste sector emissions had been expected to increase more rapidly, but improvements in waste management in several regions over the past two decades have moderated this rise. Long-term mitigation in this sector requires immediate investment in improved landfills and circular waste systems, as emissions from waste already deposited will persist in the short term.

New measurement tools

Methane monitoring capacity has expanded significantly. Satellite-based systems can now identify methane super-emitters. Ground-based sensors are becoming more accessible and can provide real-time data. These developments improve national inventories and can strengthen accountability.

However, policy action does not need to wait for perfect measurement. Current scientific understanding of source magnitudes and mitigation effectiveness is sufficient to achieve a 30% reduction between 2020 and 2030. Many of the largest reductions in oil, gas and coal can be delivered through binding technology standards that do not require high precision quantification of emissions.

The decisive years ahead

The next 2 years will be critical for determining whether existing commitments translate into emissions reductions consistent with the Global Methane Pledge.

Governments should prioritise adoption of an effective international methane performance standard for oil and gas, including through the EU Methane Regulation, and expand the reach of such standards through voluntary buyers’ clubs. National and regional authorities should introduce binding technology standards for oil, gas and coal to ensure that voluntary agreements are backed by legal requirements.

One approach to promoting better progress on methane is to develop a binding methane agreement, starting with the oil and gas sector, as suggested by Barbados’ PM Mia Mottley and other leaders. Countries must also address the deeper challenge of political and economic dependence on fossil fuels, which continues to slow progress. Without a dual strategy of reducing methane and deep decarbonisation, it will not be possible to meet the Paris Agreement objectives.

Mottley’s “legally binding” methane pact faces barriers, but smaller steps possible

The next four years will determine whether available technologies, scientific evidence and political leadership align to deliver a rapid transition toward near-zero methane energy systems, holistic and equity-based lower emission agricultural systems and circular waste management strategies that eliminate methane release. These years will also determine whether the world captures the near-term climate benefits of methane abatement or locks in higher long-term costs and risks.

The Global Methane Status Report shows that the world is beginning to change course. Delivering the sharper downward trajectory now required is a test of political will. As scientists, we have laid out the evidence. Leaders must now act on it.

The post Curbing methane is the fastest way to slow warming – but we’re off the pace appeared first on Climate Home News.

Curbing methane is the fastest way to slow warming – but we’re off the pace

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits