A record number of heat-related “emergencies” have been triggered by councils this year to help rough sleepers in England and Wales, Carbon Brief analysis reveals.

As climate change drives more heat extremes, there is a growing recognition that homeless people face a higher risk of illness and even death when temperatures soar.

This summer has been the hottest on record in the UK, with official warnings about heat-related health threats issued across every part of England and Wales.

The main tool councils have to help people sleeping rough during dangerously hot periods is the “severe weather emergency protocol” (SWEP).

Freedom-of-information (FOI) requests submitted by Carbon Brief to 93 local authorities across England and Wales with significant rough-sleeper populations reveal that SWEP use has surged this year.

Many councils have used the protocol to provide water, sunscreen and “cool spaces” for rough sleepers.

However, at least 20 councils said they have never triggered a SWEP during the summer months and others failed to provide any information when asked.

Dangerous heat

Climate change is increasing the severity of dangerously hot weather in the UK and these conditions harm certain groups more than others.

People sleeping rough are both more exposed to heat due to their living conditions and more likely to experience heat-related illness, due to underlying health conditions and other issues.

Councils shoulder much of the responsibility for helping homeless people in England – the part of the UK that faces the most extreme heat – as well as in Wales.

The main mechanism councils have to deal with weather extremes is the SWEP, which can involve giving emergency shelter to rough sleepers, among other things. There is no legal obligation to use SWEPs, meaning their implementation is not consistent or universal.

SWEPs have traditionally been a response to cold weather, but there has been growing awareness in the UK of the risk posed by heat, particularly since the extreme temperatures of summer 2022.

Charities and researchers have highlighted this issue and argued for hot-weather use of SWEPs as a necessary precaution to protect rough sleepers during heatwaves. In 2023, the UK government issued its first guidance for helping homeless people during hot weather.

Record SWEP

To investigate how local authorities are helping rough sleepers deal with heat extremes, Carbon Brief sent FOI requests to 90 councils in England and three in Wales.

This covers all areas with a sizable rough-sleeper population (see: Methodology). It also includes 33 London boroughs, which together are home to a quarter of the homeless population in England and Wales, plus the Greater London Authority.

Carbon Brief asked whether councils had been using SWEPs, how often and on which dates, during the summer months from 2022 to 2025.

This period saw the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) announce around 40 “heat-health alerts” across different parts of England, indicating temperatures that threaten public health.

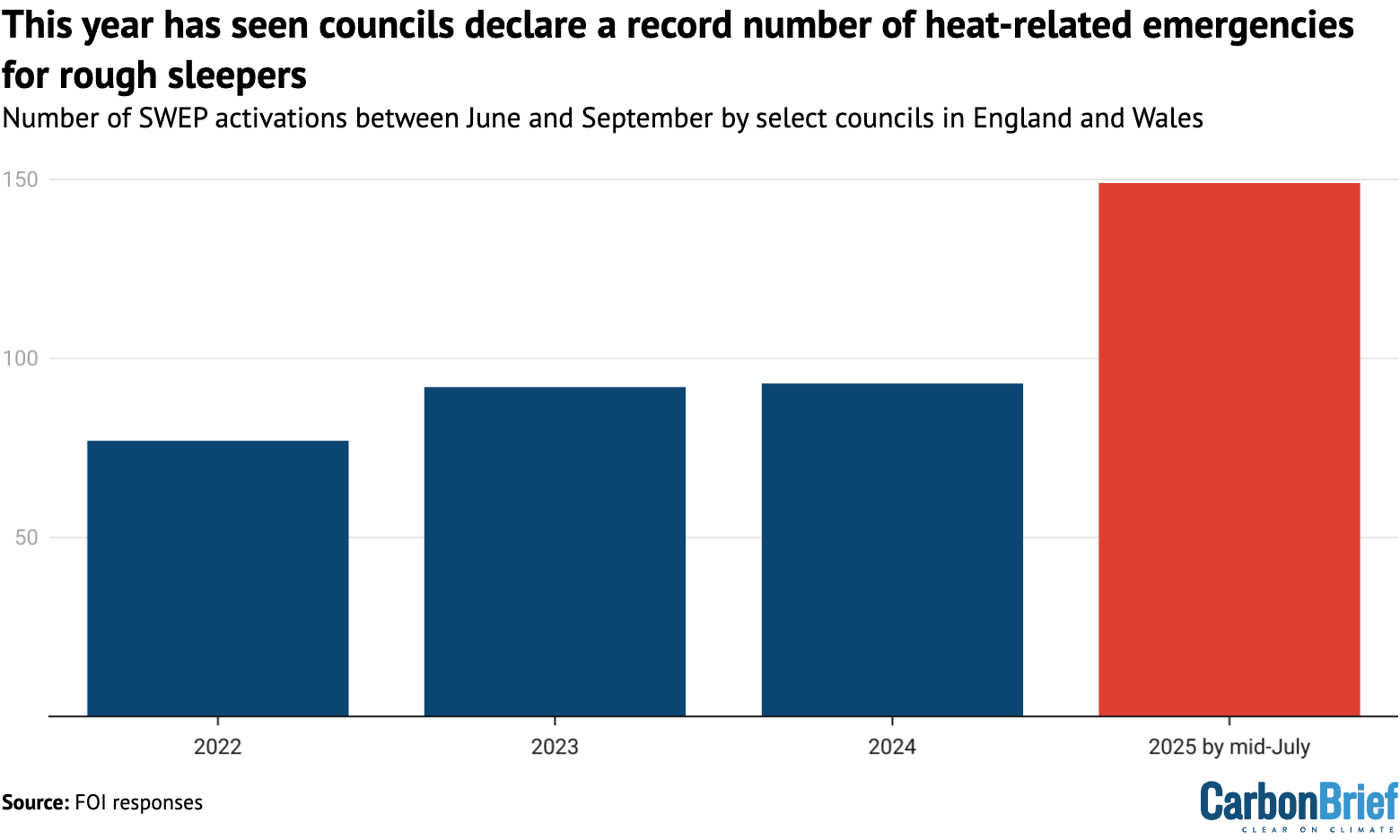

The council FOI results reveal a surge in SWEP usage in 2025, as the UK faced its hottest ever summer. Just half way through summer in mid-July, councils had already collectively triggered SWEPs at least 149 times – up from 93 in the entirety of summer in 2024, as the chart below shows.

Not all SWEP activations are the same, with some councils using it for single days and others triggering it for longer stretches.

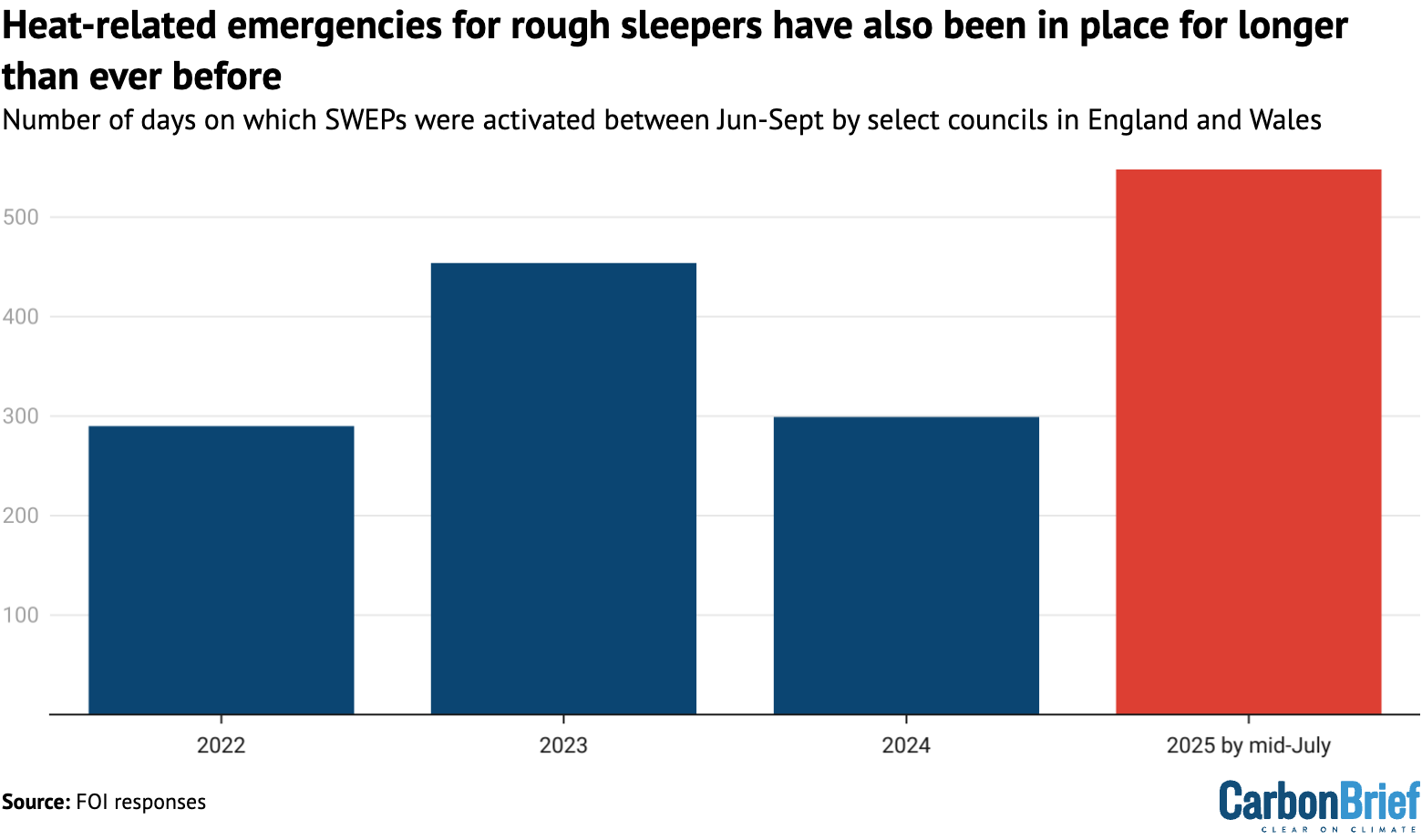

Nevertheless, roughly the same trend emerges when looking at the total number of days that councils have activated SWEPs since 2022. By mid-July, 2025 had already seen the longest period of SWEP activation, as the chart below shows.

The surge in SWEP activation mirrors both the record UK heat in 2025 and the growing salience of this issue, with more councils making use of it during the summer months. By July, 48 councils had triggered heat-related use of SWEPs this year, compared to just 36 two years earlier.

The increase may also reflect the numbers of people sleeping rough, which have surged in England over this time period, while remaining relatively steady in Wales.

‘Inadequate’ assistance

Previous analysis in 2023 by the Museum of Homelessness, a London-based organisation that researches homelessness, concluded that SWEPs were “inconsistently applied” and “inadequate”. It highlighted particular shortcomings in heat-related use of SWEPs.

Despite the surge in SWEP use this year, the data provided to Carbon Brief suggests that some councils are still not responding urgently to periods of extreme heat.

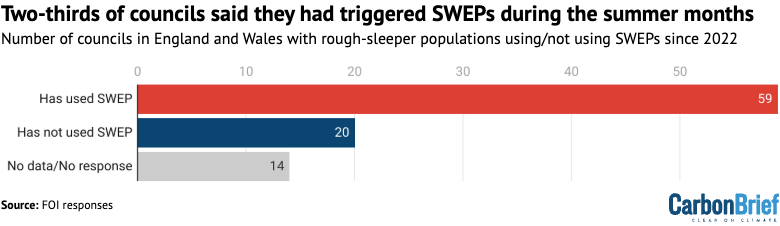

Of the 93 councils that Carbon Brief requested data from, 59 – or 63% – confirmed that they had activated SWEPs at least once during the summer months between 2022 and 2025, as shown in the figure below.

Common provisions resulting from this activation included the distribution of sunscreen, bottles of water and sun hats, as well as making “cool spaces” available and providing extra welfare checks. Most councils did not mention providing emergency accommodation.

Among the remainder, 14 councils either did not hold the data requested or never responded.

This leaves 20 councils that stated they did not trigger SWEPs at all during summers over this period, including those in Manchester, Nottingham and Cornwall.

All of the regions covered by these local authorities were issued with heat-health alerts in 2025.

Some of these councils said they were mindful of hot weather and mentioned other actions taken during these periods, some of which overlapped with SWEP responses.

Other councils, including Plymouth, Hastings and the London boroughs of Waltham Forest and Barking and Dagenham, did not mention any provisions for rough sleepers during periods of extreme heat.

Matthew Turtle, co-director of the Museum of Homelessness, tells Carbon Brief:

“These findings, like our own research, show that many councils opt not to help people who need it the most when there is extreme weather…This is not just smaller councils, but includes major towns and cities across the UK, who simply have no emergency protocol in place to protect people who are homeless during spells of extreme weather.”

Turtle argues that the use of SWEP should be made a legal duty in order to guarantee protection from extreme weather for those sleeping rough.

Researchers have argued that extreme heat should be taken more seriously by authorities when dealing with rough sleepers, with one study finding that homeless people in London were 35% more likely to be hospitalised at 25C compared to 6C. The authors suggest this is because people are better prepared for the threat of cold weather.

Dr Becky Ward, a researcher at the University of Southampton who is investigating how climate change interacts with homelessness, tells Carbon Brief that “the conversation is changing and awareness is building” about this issue. She adds:

“There’s a more fundamental need to improve the provision of shelter for people experiencing homelessness, alongside providing psychological support to address the causes and maintaining factors for people who are rough sleeping.”

Methodology

Carbon Brief obtained the list of 93 local authorities with significant rough-sleeping populations in England and Wales from the Museum of Homelessness. The criteria for this included being in one of the top 50 most populated cities in the UK, having a rough sleeping count of at least 15 people and/or being a London borough. These councils make up 28% of the 317 local authorities in England and 14% of those in Wales.

FOI requests were sent to these councils, asking for details of when SWEPs were activated and for how long over the summers of 2022-2025, as well as information about what activities this involved. (These requests were sent in mid-July, meaning data for 2025 is only for half the summer period.)

Carbon Brief asked for SWEP activations between June and September, mirroring the timescale used by the UKHSA and the Met Office for their heat-health alert service.

The results demonstrate the ad-hoc nature of SWEP use, with different councils using it in different ways and some relying on third-party organisations to coordinate their responses. Nevertheless, the combined results capture overall trends.

Some 20 councils said they did not record SWEP activations, or only kept partial records. Another five never responded to Carbon Brief’s FOI request.

In this article, Carbon Brief has used the term “rough sleeper” when referring to people sleeping outside or in other spaces not designed for people to stay. When referring to studies or datasets that cover the wider homeless population, the term “homeless” has been used.

The post Revealed: Use of heat ‘emergencies’ for rough sleepers hits record in England and Wales appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Revealed: Use of heat ‘emergencies’ for rough sleepers hits record in England and Wales

Climate Change

Leading scientists call for EPBC reforms to strengthen Great Barrier Reef protection

CANBERRA, Monday 27 October 2025 — More than 100 Australian scientists and researchers have called on the Labor Government to address deforestation in the new nature law reforms, warning that the impacts under the current Act “compound the damage caused by repeated mass bleaching events driven by climate change” to the Great Barrier Reef.

Environment Minister Murray Watt will soon table the draft bill to reform Australia’s broken nature law, the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. Leading environmental groups Greenpeace Australia Pacific, the Australian Marine Conservation Society, and the Australian Conservation Foundation coordinated the open letter with 112 leading Australian scientists, calling for the reforms to close loopholes in the Act that allow for rampant and unchecked deforestation, especially in the Great Barrier Reef catchment.

Read the letter here.

Elle Lawless, senior campaigner at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, said:

“Now is the time to act decisively for nature, and design a nature-first nature law that will do what it is set out to do: protect our environment. Toxic runoff from deforestation in the Great Barrier Reef catchment is poisoning the reef and suffocating the precious and fragile marine ecosystem. The Great Barrier Reef is a global icon, and we need a strong, robust EPBC Act that will safeguard and protect it. This is one of the most important pieces of legislation our country and our environment has and, done right, has the power to make serious and desperately needed positive changes to protect nature.”

Professor James Watson FQA, from UQ’s School of the Environment, said:

“Australia’s State of the Environment report, released by the federal government in 2021, shows that our oceans, rivers and wetlands are in serious decline. That report, and the Samuel review of the EPBC, make the point that there is a desperate need for stronger national nature laws that help protect these precious places for generations to come.

“Australia’s top environmental academics and experts have been sounding the alarm for decades: the large-scale destruction of Australia’s native woodlands, forests, wetlands and grasslands is the single biggest threat to our biodiversity. It’s driving an extinction crisis unlike anywhere else on Earth — and it’s threatening the Great Barrier Reef, one of the world’s seven natural wonders, right before our eyes.”

Continued mass deforestation threatens the Great Barrier Reef’s World Heritage status. In 2026, the World Heritage Committee will review Australia’s progress in protecting the reef and may consider placing it on the World Heritage in Danger list if major threats like deforestation are not addressed.

Recent figures from the Queensland Government show deforestation in Queensland is the worst in the nation and worsening under the current national environment law. Deforestation in the Great Barrier Reef catchment accounted for almost half (44%) of the state’s total clearing, an increase on the previous year.

Greenpeace Australia Pacific is calling for the EPBC reforms to meet four key tests:

- Stronger upfront nature protection to guide better decisions on big projects, including National Environmental Standards.

- An independent Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to enforce the laws and make decisions about controversial projects at arm’s length from politics.

- Closing deforestation loopholes that allow for harmful industries to carry out mass bulldozing across Australia.

- Consideration of the climate impacts on nature from coal and gas mines when assessing projects for approvals.

“We will continue to engage with the government constructively in the reform process but also hold decision-makers to account over these critical tests,” Lawless said.

—ENDS—

Leading scientists call for EPBC reforms to strengthen Great Barrier Reef protection

Climate Change

Close Major Deforestation Loopholes in the EPBC Act

22 October 2025

The Hon Anthony Albanese MP

Prime Minister

Parliament House

CANBERRA ACT 2600

Sent via email

To the Prime Minister, Federal Environment Minister, and Members of the Albanese Government,

As researchers who study, document and work to recover Australia’s plants and animals, insects and ecosystems, we are keenly aware of the value of nature to Australians and the world.

Australia has one of the worst rates of deforestation globally. For every 100 hectares of native woodland cleared, about 2000 birds, 15,000 reptiles and 500 native mammals will die. As scientists and experts, we have sounded the alarm for more than 30 years that the large-scale destruction of native woodlands, forests, wetlands and grasslands was the single biggest threat to the nation’s biodiversity. That is still the case today, and it is driving an extinction crisis.

New figures show that Queensland continues to lead the nation in deforestation. The latest statewide landcover and trees study (SLATS) report shows that annually 44% of all deforestation in Queensland occurs in the Great Barrier Reef catchment areas, where over 140,000 hectares are bulldozed each year.

Deforestation in Great Barrier Reef catchments is devastating one of Australia’s most iconic natural wonders. When forests and bushland are bulldozed, erosion causes debris to wash into waterways, sending sediment, nutrients and pesticides into the Reef waters. This smothers coral, fuels crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks, and reduces water quality. These impacts compound the damage caused by repeated mass bleaching events driven by climate change.

The Great Barrier Reef sustains precious marine life, supports local and global biodiversity, and underpins tourism economies and coastal communities that rely on its survival. Continued mass deforestation threatens these values and could jeopardise the Reef’s World Heritage status. In 2026 the World Heritage Committee will review Australia’s progress in protecting the Reef and may consider placing it on the World Heritage in Danger list, if key threats to the Reef, including deforestation, are not addressed.

This mass deforestation happens due to a loophole in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act, our national nature law. Exemptions allow deforestation to continue largely unregulated by the EPBC Act through a grandfathering clause from 2000 known as “continuous use”. Without meaningful reform, deforestation will continue to drive massive biodiversity loss. This loophole must be closed as part of the proposed EPBC Act reforms. The law is meant to safeguard our wildlife and our most precious places like the Great Barrier Reef. Please support closing major deforestation loopholes in the EPBC Act as an urgent and priority issue for the Federal Government.

Sincerely,

Professor James Watson, University of Queensland

Dr. Michelle Ward

Mandy Cheung

Mr Lachlan Cross

Timothy Ravasi

Gillian Rowan

Dr Graham R. Fulton, The University of Queensland

Dr Alison Peel

Dr James Richardson University of Queensland

Luke Emerson, University of Newcastle

Dr Hilary Pearl

Dr Tina Parkhurst

Dr Kerry Bridle

Dr Tracy Schultz, Senior Research Fellow, University of Queensland

Dr. Zachary Amir

Prof David M Watson, Gulbali Institute, CSU

Naomi Ploos van Amstel, PhD candidate

David Schoeman

Associate Professor Simone Blomberg, University of Queensland

Professor Euan Ritchie, Deakin University

Dr Ian Baird, Conservation Biologist

Paul Elton (ANU)

Melissa Billington

Hayden de Villiers

Professor Brett Murphy, Charles Darwin University

Professor Sarah Bekessy

Professor Anthony J. Richardson (University of Queensland)

Prof. Winnifred Louis, University of Queensland

Dr Yung En Chee, The University of Melbourne

Dr Jed Calvert, postdoctoral research fellow in wetland ecology, University of Queensland

A/Prof Daniel C Dunn, Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science, University of Queensland

Lincoln Kern, Ecologist

Professor Corey Bradshaw, Flinders University

Dr. Viviana Gonzalez, The University of Queensland

Prof. Helen Bostock

Dr Leslie Roberson

Bethany Kiss

Assoc. Prof Diana Fisher, UQ, and co-chair of the IUCN Marsupial and Monotreme Specialist Group

Dr Jacinta Humphrey, RMIT University

Professor Mathew Crowther

Christopher R. Dickman, Professor Emeritus, The University of Sydney

Fiona Hoegh-Guldberg, RMIT University

Dr Bertram Jenkins

Dr Daniela ParraFaundes

Dr Jessica Walsh

Dr. GABRIELLA scata – marine biologist, wildlife protector

Katherine Robertson

Professor Jane Williamson, Macquarie University

William F. Laurance, Distinguished Professor, James Cook University

A/Prof Deb Bower

Dr Leslie Roberson, University of Queensland

Ms Jasmine Hall, Senior Research Assistant in Coastal Wetland Biogeochemistry, Ecology and Management, Australian Rivers Institute, Griffith University

Dr Kita Ashman, Adjunct Research Associate, Charles Sturt University

Genevieve Newey

Matt Hayward

Jessie Moyses

Natalya Maitz, PhD Candidate, The University of Queensland

Christina Ritchie

Liana van Woesik, PhD Student, University of Queensland

Benjamin Lucas, PhD Researcher

A/Prof. Carissa Klein, The University of Queensland

Conrad Pratt, PhD Student, University of Queensland

Dr Ascelin Gordon, RMIT University

Professor Nicole Graham, The University of Sydney

Professor Murray Lee, University of Sydney Law School

Dr Tracy Schultz, Snr Research Fellow, University of Queensland

Libby Newton (PhD candidate, Sydney Law School)

Hannah Thomas, University of Queensland

Professor Richard Kingsford, Director of the Centre for Ecosystem Science, UNSW Sydney

Dr Anna Hopkins

Lena van Swinderen, PhD candidate at the University of Queensland

Professor Jodie Rummer, James Cook University

Dr Nita Lauren, Lecturer, RMIT University

Dr Christina Zdenek

Madeline Davey

Dr Rachel Killean, Sydney Law School

Dr. Sofía López-Cubillos

Dr Claire Larroux

Dr Alice Twomey, The University of Queensland

Zoe Gralton

Dr Robyn Gulliver

Ryan Borrett, Murdoch University

Adjunct Prof. Paul Lawrence, Griffith University, Brisbane Qld

Professor Susan Park, University of Sydney

Dr Holly Kirk, Curtin University

Deakin Distinguished Professor Marcel Klaassen

Dr Megan Evans, UNSW Canberra

Dr Amanda Irwin, The University of Sydney

Dr Keith Cardwell

Professor Don Driscoll, Deakin University

Susan Bengtson Nash

Distinguished Professor David Lindenmayer

Dr Madelyn Mangan, University of Queensland

Dr Isabella Smith

Geoff Lockwood

Dr Paula Peeters, Paperbark Writer

Prof Cynthia Riginos, University of Queensland

Dr. Sankar Subramanian

Associate Professor Zoe Richards

Dr Jessie Wells, The University of Melbourne

Professor Gretta Pecl AM, University of Tasmania

Dr April Reside, The University of Queensland

Oriana Licul-Milevoj (Ecologist)

Dr Yves-Marie Bozec, University of Queensland

Dr Julia Hazel

Dr Judit K. Szabo

Ana Ulloa

Dr Andreas Dietzel

Philip Spark – North West Ecological Services

Jonathan Freeman

Dr/ Mohamed Mohamed Rashad

Climate Change

The Ocean We’re Still Discovering

The recent discovery of Grimpoteuthis feitiana, a new species of Dumbo octopus found deep in the Pacific, is a reminder of something both humbling and urgent: we still know so little about the ocean that shapes our lives. This fragile, finned creature, gliding silently more than a kilometer beneath the waves, has lived in these waters long before we mapped them, and its story is only now coming to light.

What moves me most about this discovery is not just the Dumbo octopus itself, but how it bridges science and culture. Its name draws inspiration from the flying apsaras of China’s Dunhuang murals, those graceful, winged figures that seem to dance through air and imagination. It reminds me that the deep sea has always held a place in our collective human story, — not only in myths and art, but in the ways we relate to nature, learn from it, and find meaning within it.

Pasifika connection to the ocean

For us in the Pacific, the ocean is more than a body of water. It is our identity, our culture, our history. Our ancestors read the seas to navigate, to survive, to connect communities scattered across islands. Discoveries like this Dumbo octopus awaken something deeper in me, — a sense that the ocean is alive with stories and wisdom we are only beginning to rediscover. And with that understanding comes a responsibility to protect it.

Each new species like the Dumbo octopus, each glimpse into the deep, is a warning as much as it is a wonder. The creatures of the abyss live slow, deliberate lives in fragile ecosystems, shaped by balance and patience. Deep-sea mining, pollution, and climate change threaten to erase them before we even learn their names. Protecting the Pacific’s oceans is not an abstract act of conservation; it is an act of cultural preservation, of love for our home, and for the unseen life that sustains us all.

Grimpoteuthis feitiana is more than a scientific discovery. It is a reminder that the ocean is still full of life, mystery, and wisdom — and that we have a duty to ensure these depths remain wild, healthy, and alive, for us and for the generations yet to come.

Reflection by Raeed Ali

Pacific Community Mobiliser

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change3 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Greenhouse Gases3 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change1 year ago

Climate Change1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy4 months ago

US Grid Strain, Possible Allete Sale