Keeping track of money is one of the most important measures a company can take to reduce its climate impact. We spoke with Ingmar Rentzhog from the media platform We Don’t Have Time, which works for climate action and advocates making a difference for the climate by moving money.

“What many companies don’t realize is that their biggest climate footprint doesn’t come from their own operations, but from the company’s bank accounts and pension funds for their employees, as well as from other financial investments. This doesn’t apply to companies in the steel and concrete industries, for example, but for many other companies, it’s actually the money that is the culprit,” says Ingmar Rentzhog, We Don’t Have Time.

Ingmar refers to the latest Carbon Bankroll report, which shows that the total carbon emissions for some companies in the service and ICT sectors would more than double if emissions from cash in the bank were included.

“The main reason is probably that the knowledge about the climate impact of money is far too low, both among companies, politicians, and individuals. That’s why We Don’t Have Time launched the Move The Money campaign, to raise awareness and increase knowledge about this. The more large established organisations that move their money away from companies that refuse to transition, the more it opens up for political regulation. It is much easier for politicians to regulate something when large financial institutions do not have a financial interest in that activity,” continues Ingmar Rentzhog.

Ingmar Rentzhog’s top three tips for those who want to climate-proof their company’s money management:

- Make the company’s cash sustainable by moving the money to a bank that has phased out or is about to phase out lending and investments in fossil fuels.

- Do the same with your employees’ pension funds.

- Communicate widely that you have done this and why it is so important.

At wedonthavetime.org/movethemoney, you can find concrete help on how your company can proceed, and there is also a database of how much banks have invested in fossil assets.

“I wish everyone realized how deep the climate crisis actually is and how little time we have to act to prevent the worst scenarios. I also wish everyone knew how incredibly easy it is to make a big impact by simply moving money,” concludes Ingmar Rentzhog.

The post “I wish everyone knew how incredibly easy it is to make a big impact by simply moving money.” appeared first on GoClimate Blog.

“I wish everyone knew how incredibly easy it is to make a big impact by simply moving money.”

Greenhouse Gases

Celebrating the launch of BRIDGE: CCL’s new advocacy program for 2026

Celebrating the launch of BRIDGE: CCL’s new advocacy program for 2026

By Elissa Tennant, CCL Director of Marketing

The start of a new year always brings a sense of renewal. With every January comes a fresh start and a chance to decide how we’ll show up for the next 12 months. This sentiment was reflected in CCL’s first Monthly Meeting of the year, which took place Saturday, January 10.

CCL Executive Director Ricky Bradley started the call with an organizational update. In 2026, CCL is looking forward to applying our new strategic plan, leaning into our relational advocacy roots, and making progress on key policy areas. Ricky also emphasized the importance of our volunteers and gratitude for CCLers’ persistence, strength, and belief in our climate work.

From there, CCL Vice President of Field Operations, Dr. Brett Cease, joined the call to introduce CCL’s newest initiative, which will shape the way we approach our work in 2026: BRIDGE. If you want to move Congress forward on climate change, and you understand it’s going to take something above and beyond the usual tactics, BRIDGE is the program for you.

What is BRIDGE?

BRIDGE stands for Building Relationships in Dialogue, Growth, and Engagement. “At its heart, it’s a volunteer training program designed to help us become even more effective climate advocates,” said Brett. “It will deepen our skills in communication, relationship-building, and strategic engagement.”

CCL has always believed that relationships truly can change what is possible on climate progress. When thousands of CCL volunteers across the country practice the same shared approach — listening well, aligning messages with values, and building durable relationships — our impact compounds. We become more consistent, more strategic, and more aligned in how we work with communities and Members of Congress across the political spectrum.

What will volunteers actually learn?

The framework is grouped into trainings of three within three successive units. Each unit will roll out throughout one quarter of 2026. Throughout the first unit, CCL volunteers learn the foundations of relational advocacy.

- Unit 1 (Jan.-Mar.): Start by exploring how behavioral science has helped us understand how people arrive at their beliefs and why that matters for climate advocacy. Then dive into Moral Foundations Theory and practice moral reframing.

- Unit 2 (April-June): Learn how to research your Member of Congress, understand their pressures and priorities, and identify realistic next-step actions. Follow this up with a lesson on the Scale of Support, which helps volunteers recognize where a policymaker currently stands and how to work together on policy.

- Unit 3 (July-Sept.): Practice techniques drawn from social sciences — things like active listening, conflict de-escalation, motivational interviewing, and persuasive communications — to build confidence engaging in conversations that are hopeful, respectful, and constructive, even when there’s disagreement.

And importantly, this isn’t just material we pulled from books — we’ve been in touch with nearly all of the researchers whose work we’re using, and they’re aware of how BRIDGE is applying their theories in the real world.

How will BRIDGE be rolled out across the year?

One of the most important parts of BRIDGE is that it isn’t a one-time training or something volunteers are expected to absorb all at once. It’s a comprehensive, step-by-step process. Each month will focus on a new BRIDGE topic, and with material and practice exercises woven through our monthly meetings, action sheets, and deep dive training sessions

The first training session, which took place Jan. 22, helped volunteers further explore the first section of Unit 1. The event aimed to give space for discussion, examples, role-play, and reflection with other volunteers around for support.

“It’s exciting to see how many people are already excited about BRIDGE and invested in building more effective advocacy skills,” said Brett. ”More than 200 volunteers came to our first ‘deep dive’ training.”

How does BRIDGE help in this polarized political moment?

BRIDGE is designed to help us respond in this moment and build a healthier political landscape for tomorrow — by building the kinds of trust, connection, and cross-difference communication that strengthens democratic life from the ground up.

“We’re launching BRIDGE at a time when many Americans have diverse and important concerns about our current state of democracy,” said Brett. “A lot of political discourse in our times is built around shaming, calling out, or ‘owning’ the other side.”

Polarization is the problem. Relationship-building is the strategy. BRIDGE is the tool.

How can I get started?

BRIDGE training modules will open throughout the year on CCL Community. The first module (Unit 1, Training 1), “Understanding Ourselves to Better Understand Others,” is available here. The first deep dive training is live now.

RIDGE exists because the policies we need don’t advance through talking past one another — they advance through relationships. When volunteers are trained not just to advocate, but to listen, to connect, and to invite people in, that’s how we make a difference.

Access BRIDGE Unit 1 now

The post Celebrating the launch of BRIDGE: CCL’s new advocacy program for 2026 appeared first on Citizens' Climate Lobby.

Celebrating the launch of BRIDGE: CCL’s new advocacy program for 2026

Greenhouse Gases

Climate change and La Niña made ‘devastating’ southern African floods more intense

“Exceptionally heavy” rainfall that led to deadly flooding across southern Africa in recent weeks was made more intense by a combination of climate change and La Niña.

This is according to a rapid attribution study by the World Weather Attribution service.

From late December 2025 to early January, south-eastern Africa was hit hard by intense downpours that resulted in more than a year’s worth of rain falling in some areas in just a few days, according to the study.

This led to severe flooding that left at least 200 people dead, thousands sheltering in temporary accommodation and tens of thousands of hectares of farmland waterlogged.

The analysis finds that periods of intense rainfall over southern Africa have become 40% more severe since pre-industrial times, according to observations.

The authors say they were unable to calculate how much of this increase was driven specifically by climate change, due to limitations in how climate models simulate African rainfall.

However, the study notes that the researchers “have confidence that climate change has increased both the likelihood and the intensity” of the rainfall.

The authors also note that the El Niño-Southern Oscillation phenomenon played a role in the “devastating” flooding, estimating that a La Niña event made the rainfall around five times more likely.

Major disruption

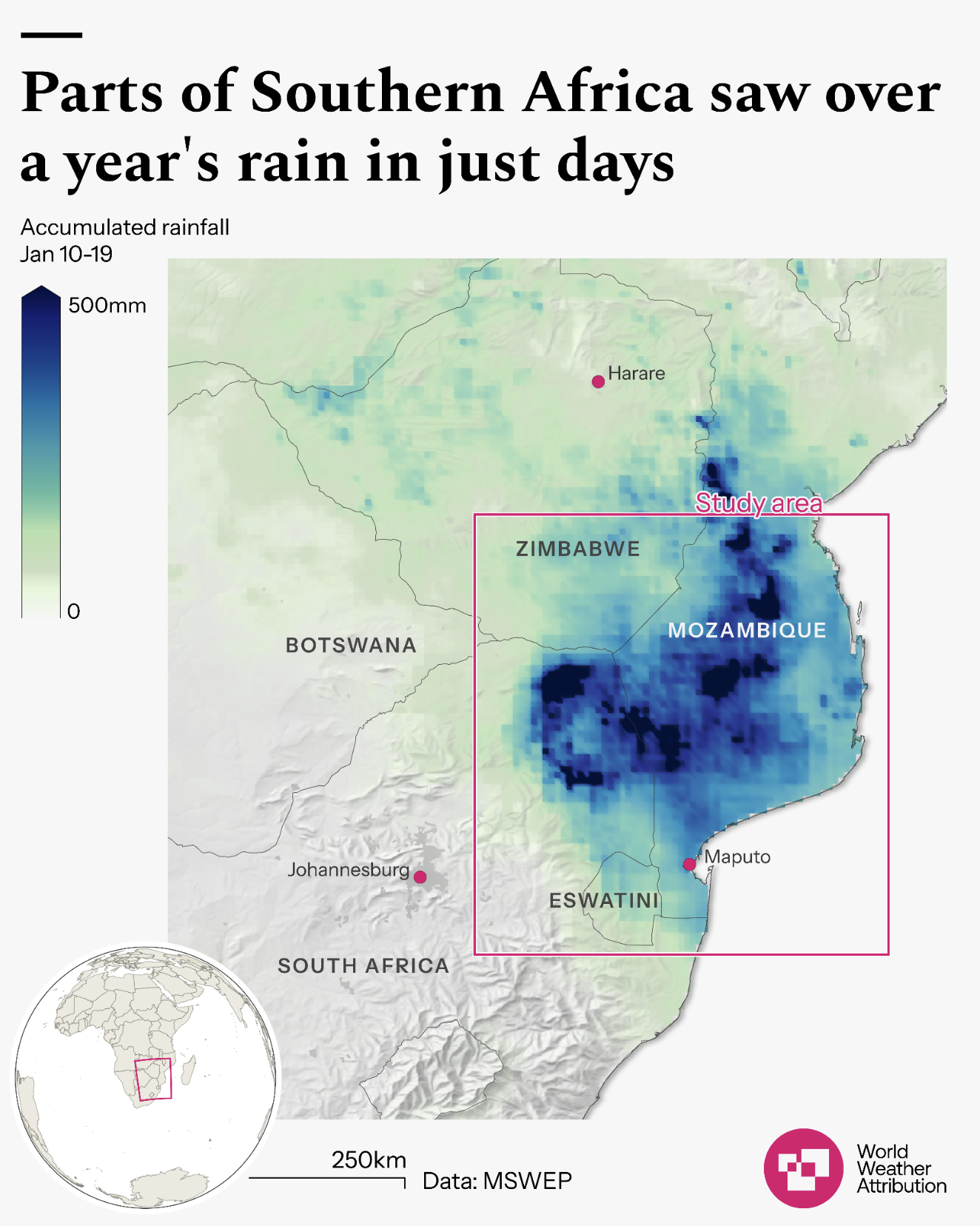

The heavy rainfall started on 26 December last year and intensified from early January. The most-extreme rainfall took place between 10 and 19 January.

The countries most affected by the floods, and analysed by the study, are Eswatini, Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe, with some areas receiving up to 200mm of rain, according to the study authors.

Study author Bernardino Nhantumbo – a researcher at Mozambique’s National Institute of Meteorology – told a press briefing that in just two or three days, some areas recorded the amount of rainfall that is “expected for the whole rainy season”.

The map below shows the areas most affected by intense rainfall over 10-19 January. Darker blue indicates a greater accumulation of rainfall, while light green indicates less rainfall. The pink box shows the study area.

In Mozambique, the floods damaged nearly 5,000km of roads, which has hindered the transport of goods and affected pharmaceutical supply chains, the study says. In Zimbabwe, bridges, roads and infrastructure were “significantly damaged or destroyed”.

More than 75,000 people have been affected by the floods in Mozambique, according to the study. BBC News reported the floods were the worst seen “in a generation” in the country.

Dr Izidine Pinto, a climate scientist from Mozambique currently working at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, told a press briefing that the country was particularly affected because it “lies downstream of major river basins”.

The flooding prompted Mozambique’s education minister to consider rescheduling the start of the academic year, according to Channel Africa.

In South Africa, the country’s weather service said that areas receiving more than 50mm of rain over 11-13 January were “widespread”, with some places seeing up to 200mm.

South Africa’s Kruger National Park – the largest national park in South Africa – was severely damaged by floods and temporarily closed after several rivers burst their banks, reported TimesLIVE.

The South African news outlet quoted environment minister Willie Aucamp as saying: “The indication is that it will take as long as five years to repair all the bridges and roads and other infrastructure.”

Extreme rainfall

The peak of the rainy season in southern Africa falls between December and February.

To put the extreme rainfall into its historical context and determine how unlikely it was, the authors analysed a timeseries of 10-day maximum rainfall data for the December-February season.

They find that in today’s climate, extreme rainfall events of the scale seen this year in southern Africa would be expected only once every 50 years.

They add that such events have become “significantly more intense”, with observational data showing a 40% increase in rainfall severity since pre-industrial times.

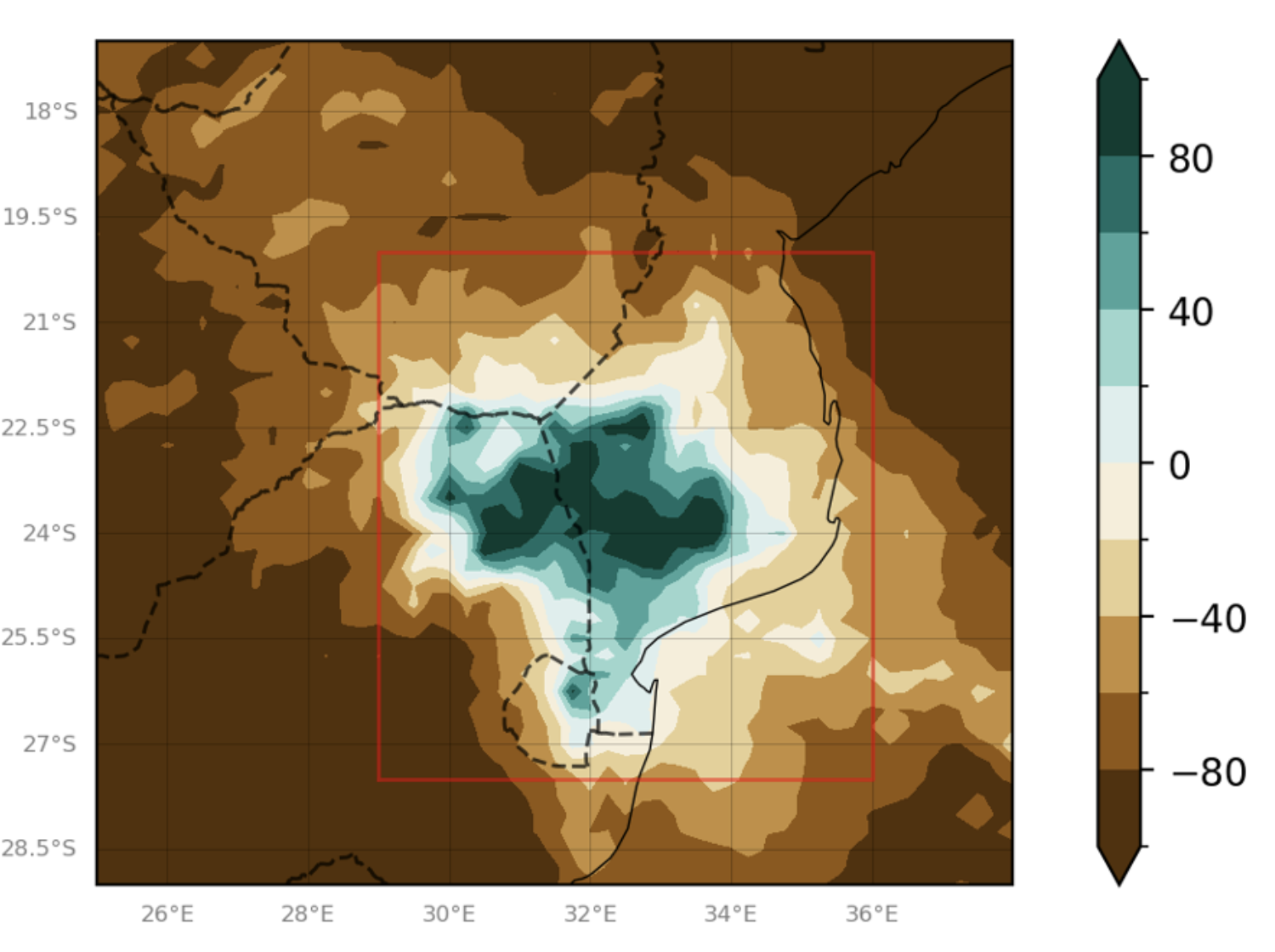

The map below shows accumulated rainfall over Eswatini, Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe over 10-19 January, as a percentage of the average December-February rainfall for the region over 1991-2020.

Green shading indicates that the rainfall in 2026 was higher than in 1991-2020, while brown indicates that it was lower. The red box indicates the study region.

The study explains that in January and February, rainfall patterns in southern Africa are “strongly influenced” by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a naturally occurring climate phenomenon that affects global temperatures and regional weather patterns.

La Niña is the “cool” phase of ENSO, which typically brings wetter weather to southern Africa.

Pinto told the press briefing that “most past extreme rainfall events [in the region] have occurred during La Niña years”.

The authors estimate that the current weak La Niña event made the extreme rainfall five times more likely and increased the intensity of the event by around 22%.

For attribution studies, which identify the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change on extreme weather events, scientists typically use climate models to simulate and compare worlds with and without global warming.

However, many models have limitations in their simulations of African rainfall. In this study, the authors found that the models available to them cannot “adequately capture” the influence of ENSO on rainfall in the region.

Study author Prof Fredi Otto, a professor in climate science at the Imperial College London, told a press briefing that these limitations are “well known”. They stem, in part, because the models were “developed outside of Africa” by modellers with different priorities, she explained.

This means that the authors were unable to calculate how much more intense or likely the rainfall event was specifically as a result of human-caused warming.

However, Otto explained that the authors are “very, very confident that climate change did increase the likelihood and intensity of the rainfall” to some extent. This is because the observations all show an increase in rainfall over time and other existing literature supports this assumption, she added.

She told the press briefing that the results of this study were “definitely not 100% satisfactory”, adding that this study will “definitely not be the last of its kind in this region”.

(These findings are yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. However, the methods used in the analysis have been published in previous attribution studies.)

Vulnerability

The study warns that the flooding “exposed deep and persistent social vulnerability in the region”.

The authors say that a large proportion of the population – especially in urban areas – live in poor housing with “inadequate planning and insufficient provision of basic services”.

Paola Emerson, head of office at the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in Mozambique, told a UN press briefing about the flooding that nearly 90% of people in the country live in traditional adobe houses that “basically melt after a few days’ rains”.

In a WWA press release, study author Nhantumbo explained:

“When 90% of homes are made of sun-dried earth, they simply cannot withstand this much rain. The structural collapse of entire villages is a stark reminder that our communities and infrastructure are now being tested by weather they are just not designed to endure.”

Study author Renate Meyer – an adviser with the conflict and climate team at the Red Cross Red Crescent Centre – said in a WWA press briefing that the “recurring frequency of hazards such as drought and extreme rainfall have had a significant impact on communities experiencing, amongst others, displacement, health challenges, socioeconomic loss and psychological distress”.

For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) said in a press release that the event had disrupted access to health services and increased the risks of water- and mosquito-borne diseases, as well as respiratory infections across southern Africa.

Meyer explained that the countries included in this study have “substantial populations living below or near the poverty line with limited savings, low insurance cover and a high dependence on climate sensitive livelihoods”.

The post Climate change and La Niña made ‘devastating’ southern African floods more intense appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate change and La Niña made ‘devastating’ southern African floods more intense

Greenhouse Gases

Climate change could lead to 500,000 ‘additional’ malaria deaths in Africa by 2050

Climate change could lead to half a million more deaths from malaria in Africa over the next 25 years, according to new research.

The study, published in Nature, finds that extreme weather, rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns could result in an additional 123m cases of malaria across Africa – even if current climate pledges are met.

The authors explain that as the climate warms, “disruptive” weather extremes, such as flooding, will worsen across much of Africa, causing widespread interruptions to malaria treatment programmes and damage to housing.

These disruptions will account for 79% of the increased malaria transmission risk and 93% of additional deaths from the disease, according to the study.

The rest of the rise in malaria cases over the next 25 years is due to rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns, which will change the habitable range for the mosquitoes that carry the disease, the paper says.

The majority of new cases will occur in areas already suitable for malaria, rather than in new regions, according to the paper.

The study authors tell Carbon Brief that current literature on climate change and malaria “often overlooks how heavily malaria risk in Africa is today shaped by climate-fragile prevention and treatment systems”.

The research shows the importance of ensuring that malaria control and primary healthcare is “resilient” to the extreme weather, they say.

Malaria in a warming world

Malaria kills hundreds of thousands of people every year. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 610,000 people died due to the disease in 2024.

In 2024, Africa was home to 95% of malaria cases and deaths. Children under the age of five made up three-quarters of all African malaria deaths.

The disease is transmitted to humans by bites from mosquitoes infected with the malaria parasite. The insects thrive in high temperatures of around 29C and need stagnant or slow-moving water in which to lay their eggs. As such, the areas where malaria can be transmitted are heavily dependent on the climate.

There is a wide body of research exploring the links between climate change and malaria transmission. Studies routinely find that as temperatures rise and rainfall patterns shift, the area of suitable land for malaria transmission is expanding across much of the world.

Study authors Prof Peter Gething and Prof Tasmin Symons are researchers at the Curtin University’s school of population health and the Malaria Atlas Project from the The Kids Research Institute, Australia.

They tell Carbon Brief that this approach does not capture the full picture, arguing that current literature on climate change and malaria “often overlooks how heavily malaria risk in Africa is today shaped by climate-fragile prevention and treatment systems”.

The paper notes that extreme weather events are regularly linked to surges in malaria cases across Africa and Asia. This is, in-part, because storms, heavy rainfall and floods leave pools of standing water where mosquitoes can breed. For example, nearly 15,000 cases of malaria were reported in the aftermath of Cyclone Idai hitting Mozambique in 2019.

However, the study authors also note that weather extremes often cause widespread disruption, which can limit access to healthcare, damage housing or disrupt preventative measures such as mosquito nets. These factors can all increase vulnerability to malaria, driving the spread of the disease.

In their study, the authors assess both the “ecological” effects of climate change – the impacts of temperature and rainfall changes on mosquito populations – and the “disruptive” effects of extreme weather.

Mosquito habitat

To assess the ecological impacts of climate change, the authors first identify how temperature, rainfall and humidity affect mosquito lifecycles and habitats.

The authors combine observational data on temperature, humidity and rainfall, collected over 2000-22, with a range of datasets, including mosquito abundance and breeding habitat.

The authors then use malaria infection prevalence data, collected by the Malaria Atlas Project, which describes the levels of infection in children aged between two and 10 years old.

Symons and Gething explain that they can then use “sophisticated mathematical models” to convert infection prevalence data into estimates of malaria cases.

Comparing these datasets gives the authors a baseline, showing how changes in climate have affected the range of mosquitoes and malaria rates across Africa in the early 21st century.

The authors then use global climate models to model future changes over 2024-49 under the SSP2-4.5 emissions pathway – which the authors describe as “broadly consistent with current international pledges on reduced greenhouse gas emissions”.

The authors also ran a “counterfactual” scenario, in which global temperatures do not increase over the next 25 years. By comparing malaria prevalence in their scenarios with and without climate change, the authors could identify how many malaria cases were due to climate change alone.

Overall, the ecological impacts of climate change will result in only a 0.12% increase in malaria cases by the year 2050, relative to present-day levels, according to the paper.

However, the authors say that this “minimal overall change” in Africa’s malaria rates “masks extensive geographical variation”, with some areas seeing a significant increase in malaria rates and others seeing a decrease.

Disruptive extremes

In contrast, the study estimates that 79% of the future increase in malaria transmission will be due to the “disruptive” impacts of more frequent and severe weather extremes.

The authors explain that extreme weather events, such as flooding and cyclones, can cause extensive damage to housing, leaving people without crucial protective equipment such as mosquito nets.

It can also destroy other key infrastructure, such as roads or hospitals, preventing people from accessing healthcare. This means that in the aftermath of an extreme weather event, people face a greater risk of being infected with malaria.

The climate models run by the study authors project an increase in “disruptive” extreme weather events over the next 25 years.

For example, the authors find that by the middle of the century, cyclones forming in the Indian Ocean will become more intense, with fewer category 1 to category 4 events, but more frequent category 5 events. They also find that climate change will drive an increase in flooding across Africa.

The study finds that without mitigation measures, these disruptive events will drive up the risk of malaria – especially in “main river systems” and the “cyclone-prone coastal regions of south-east Africa”.

Between 2024 and 2050, 67% of people in Africa will see their risk of catching malaria increase as a result of climate change, the study estimates.

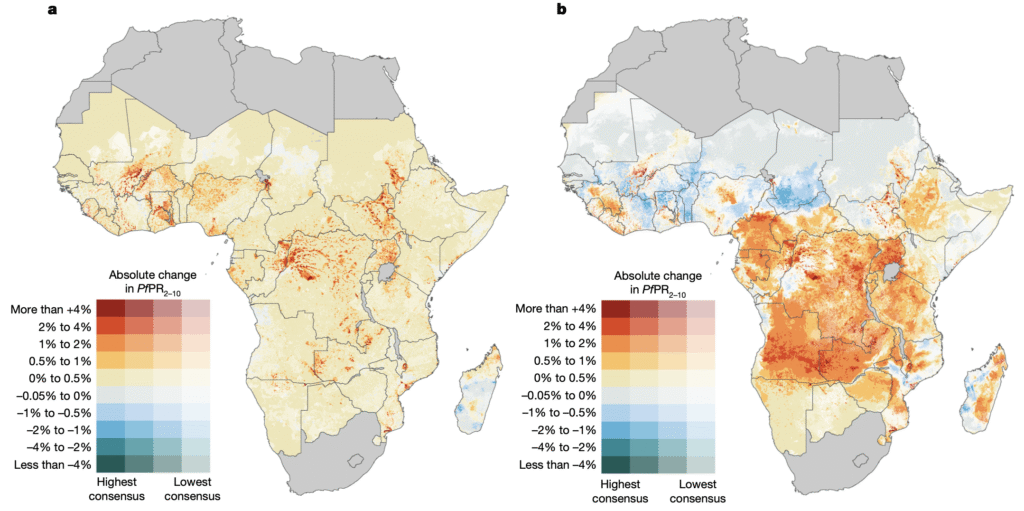

The map below shows the percentage change in malaria transmission rate in the 2040s due to the disruptive impacts of climate change alone (left) and a combination of the disruptive and ecological impacts (right), compared to a scenario in which there is no change in the climate. Red and yellow indicate an increase in malaria risk, while blue indicates a reduction.

Colours in lighter shading indicate lower model confidence, while stronger colours indicate higher model confidence.

The maps show that the “disruptive” effects of climate change have a more uniform effect, driving up malaria risk across the entire continent.

However, there is greater regional variation when these effects are combined with “ecological” drivers.

The authors find that warming will increase malaria risk in regions where the temperature is currently too low for mosquitoes to survive. This includes the belt of lower latitude southern Africa, including Angola, southern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Zambia, as well as highland areas in Burundi, eastern DRC, Ethiopia, Kenya and Rwanda.

Meanwhile, they find that warming will drive down malaria transmission in the Sahel, as temperatures rise above the optimal range for mosquitoes.

Rising risk

The combined “disruptive” and “ecological” impacts of climate change will drive an additional 123m “clinical cases” of malaria across Africa, even if the current climate pledges are met, the study finds.

This will result in 532,000 additional deaths from malaria over the next 25 years, if the disease’s mortality rate remains the same, the authors warn.

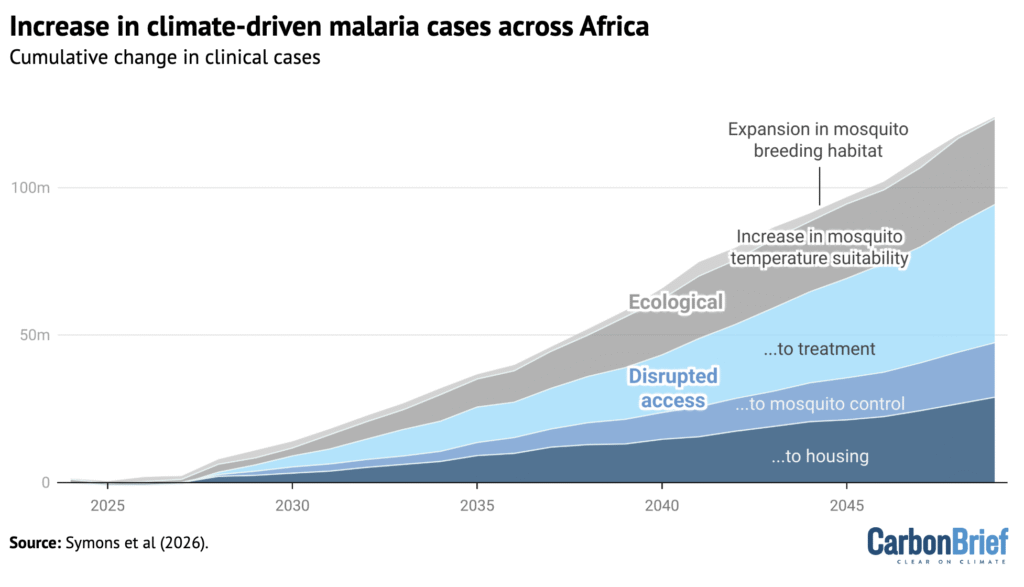

The graph below shows the increase in clinical cases of malaria projected across Africa over the next 25 years, broken down into the different ecological (yellow) and disruptive (purple) drivers of malaria risk.

However, the authors stress that there are many other mechanisms through which climate change could affect malaria transmission – for example, through food insecurity, conflict, economic disruption and climate-driven migration.

“Eradicating malaria in the first half of this century would be one of the greatest accomplishments in human history,” the authors say.

They argue that accomplishing this will require “climate-resilient control strategies”, such as investing in “climate-resilient health and supply-chain infrastructure” and enhancing emergency early warning systems for storms and other extreme weather.

Dr Adugna Woyessa is a senior researcher at the Ethiopian Public Health Institute and was not involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief that the new paper could help inform national malaria programmes across Africa.

He also suggests that the findings could be used to guide more “local studies that address evidence gaps on the estimates of climate change-attributed malaria”.

Study authors Symons and Gething tell Carbon Brief that during their study, they interviewed “many policymakers and implementers across Africa who are already grappling with what climate-resilient malaria intervention actually looks like in practice”.

These interventions include integrating malaria control into national disaster risk planning, with emergency responses after floods and cyclones, they say. They also stress the need to ensure that community health workers are “well-stocked in advance of severe weather”.

The research shows the importance of ensuring that malaria control and primary healthcare is “resilient” to the extreme weather, they say.

The post Climate change could lead to 500,000 ‘additional’ malaria deaths in Africa by 2050 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate change could lead to 500,000 ‘additional’ malaria deaths in Africa by 2050

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits