US President Donald Trump grabbed the headlines again at the World Economic Forum, launching his “Board of Peace” for Gaza on the final day of the gathering of political and business leaders. But discussions on climate and energy continued below the media radar.

Climate Home New has been listening in – here are some of the best bits.

Occidental boss: Banks “coming back” to oil and gas

Banks which have previously refused to fund oil and gas projects are “coming back” to the industry, an American oil executive told an event at Davos on Thursday.

Vicki Hollub, CEO of Occidental Petroleum, the world’s 28th most polluting company, said in a conversation with US Energy Secretary Chris Wright that “there was a time” when banks shunned her industry. That, she added, had been a “burden”.

“But some of those banks are now coming back – and in fact I talked to one yesterday that had kind of abandoned us and now are back and wanting to do business in the oil and gas industry,” she said, without revealing the name of the bank.

A report by the London School of Economics last year found that many banks weakened their policies against fossil fuel lending in 2025 and the Net Zero Banking Alliance shut down in October 2025, after many – particularly American – banks left the green initiative.

Azeri oil chief says no spare cash for green tech

European investors appear to have been slower to abandon their climate commitments. Rovshan Najaf, president of SOCAR (the State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic), told a separate Davos panel that his company struggles to get financing from most European commercial banks for its oil and gas operations.

As a result, he said, the firm must use its available cash to fund oil and gas projects – “one of the priority areas” – leaving it with little free capital to invest in lower-carbon fuels like green hydrogen and ammonia, or emissions-reducing technologies such as carbon capture or methane abatement.

Recent COP hosts Brazil and Azerbaijan linked to “super-emitting” methane plumes

Unlike renewables and electrification, there is still no commercial case for funding those potential breakthroughs at scale and making them affordable, he added.

“There should be a big picture approach to all energy mixes and how we can free up the capital [for decarbonisation],” he argued.

Najaf promised last year that the firm would achieve near-zero methane emissions in its oil and gas production by 2035. But, as Climate Home News reported recently, the latest data available from SOCAR shows that its methane emissions more than tripled from 2023 to 2024, when the country hosted COP29.

US promotes fossil gas to “ally” Europe

One key reason why SOCAR has been investing in more gas production and export capacity is deals with European governments to help replace Russian gas after the invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

At Davos, Wright praised Europe for being close to independence from Russian gas, saying it could achieve that goal in the next year or two.

He called for the EU to weaken its environmental regulations on methane – a particularly potent greenhouse gas – to enable American fossil gas to displace Russian supplies.

Despite President Donald Trump’s recent threats to take over Greenland, which have caused a growing rift with European leaders, Wright insisted Europe is “our main ally in defending the Western world”.

The US supplies about a quarter of the EU’s gas imports, a percentage which has risen since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But overall, the EU’s gas imports are declining and are predicted to keep falling, as the continent moves towards clean energy. On Thursday, data published by think-tank Ember showed that wind and solar generated more EU electricity than fossil fuels in 2025, producing a record 30% of EU power, ahead of fossil fuels at 29%.

“New era of climate extremes” as global warming fuels devastating impacts in 2025

On climate change, Wright played down the threat, saying that deaths from extreme weather have declined over the last 100 years.

While floods, droughts, storms and heatwaves are becoming more frequent and intense as the planet warms, Wright is correct in saying they have caused fewer deaths over this long time period.

This has largely been the result of economic development and, more recently, climate resilience measures of the kind the Trump administration has drastically reduced US funding for.

The post Climate at Davos: Oil execs bemoan “burden” of bank boycotts appeared first on Climate Home News.

Climate at Davos: Oil execs bemoan “burden” of bank boycotts

Climate Change

Analysis: China’s CO2 emissions have now been ‘flat or falling’ for 21 months

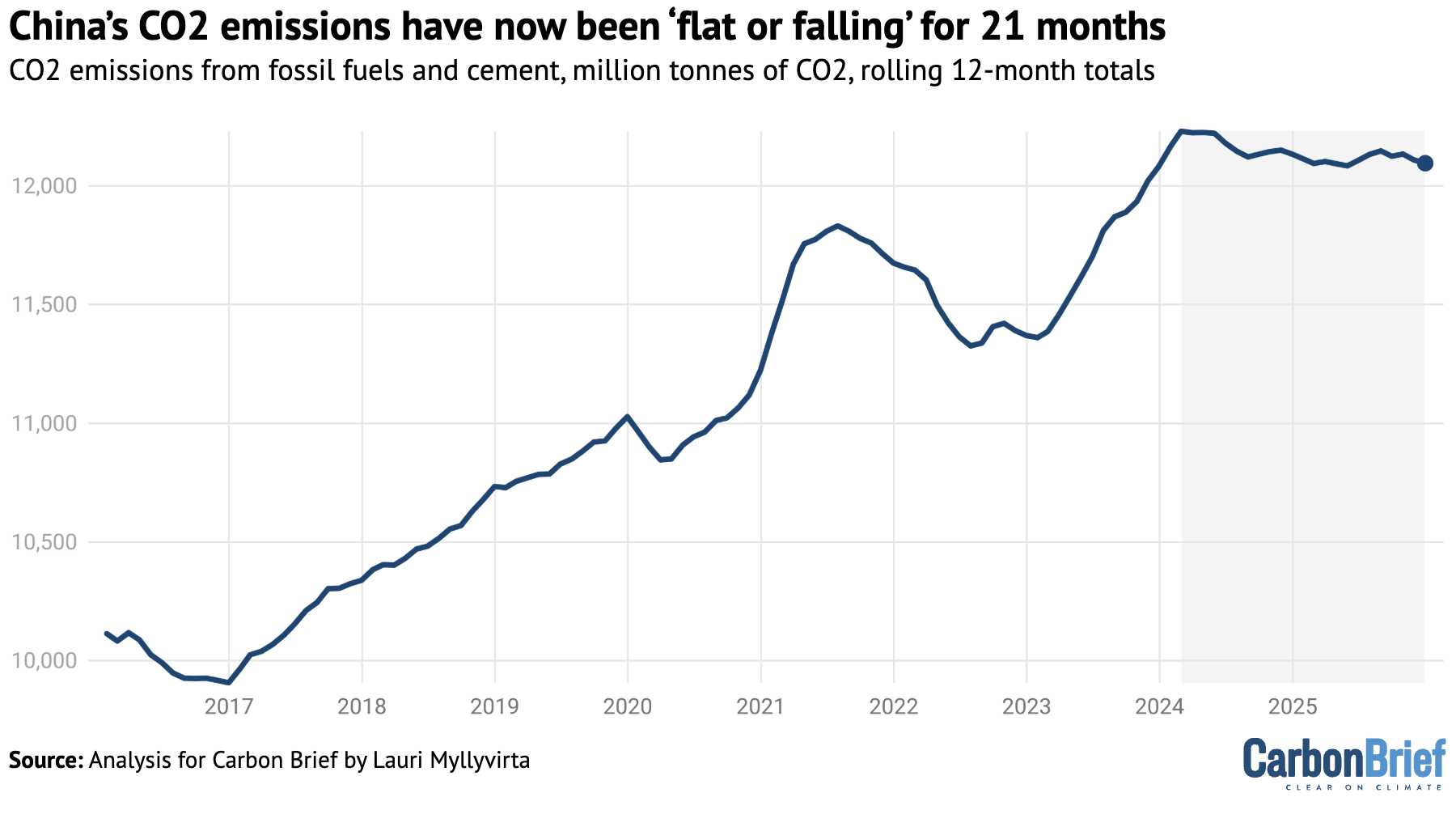

China’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions fell by 1% in the final quarter of 2025, likely securing a decline of 0.3% for the full year as a whole.

This extends a “flat or falling” trend in China’s CO2 emissions that began in March 2024 and has now lasted for nearly two years.

The new analysis for Carbon Brief shows that, in 2025, emissions from fossil fuels increased by an estimated 0.1%, but this was more than offset by a 7% decline in CO2 from cement.

Other key findings include:

- CO2 emissions fell year-on-year in almost all major sectors in 2025, including transport (3%), power (1.5%) and building materials (7%).

- The key exception was the chemicals industry, where emissions grew 12%.

- Solar power output increased by 43% year-on-year, wind by 14% and nuclear 8%, helping push down coal generation by 1.9%.

- Energy storage capacity grew by a record 75 gigawatts (GW), well ahead of the rise in peak demand of 55GW.

- This means that growth in energy storage capacity and clean-power output topped the increases in peak and total electricity demand, respectively.

The CO2 numbers imply that China’s carbon intensity – its fossil-fuel emissions per unit of GDP – fell by 4.7% in 2025 and by 12% during 2020-25.

This is well short of the 18% target set for that period by the 14th five-year plan.

Moreover, China would now need to cut its carbon intensity by around 23% over the next five years in order to meet one of its key climate commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Whether Chinese policymakers remain committed to this target is a key open question ahead of the publication of the 15th five-year plan in March.

This will help determine if China’s emissions have already passed their peak, or if they will rise once again and only peak much closer to the officially targeted date of “before 2030”.

‘Flat or falling’

The latest analysis shows China’s CO2 emissions have now been flat or falling for 21 months, starting in March 2024. This trend continued in the final quarter of 2025, when emissions fell by 1% year-on-year.

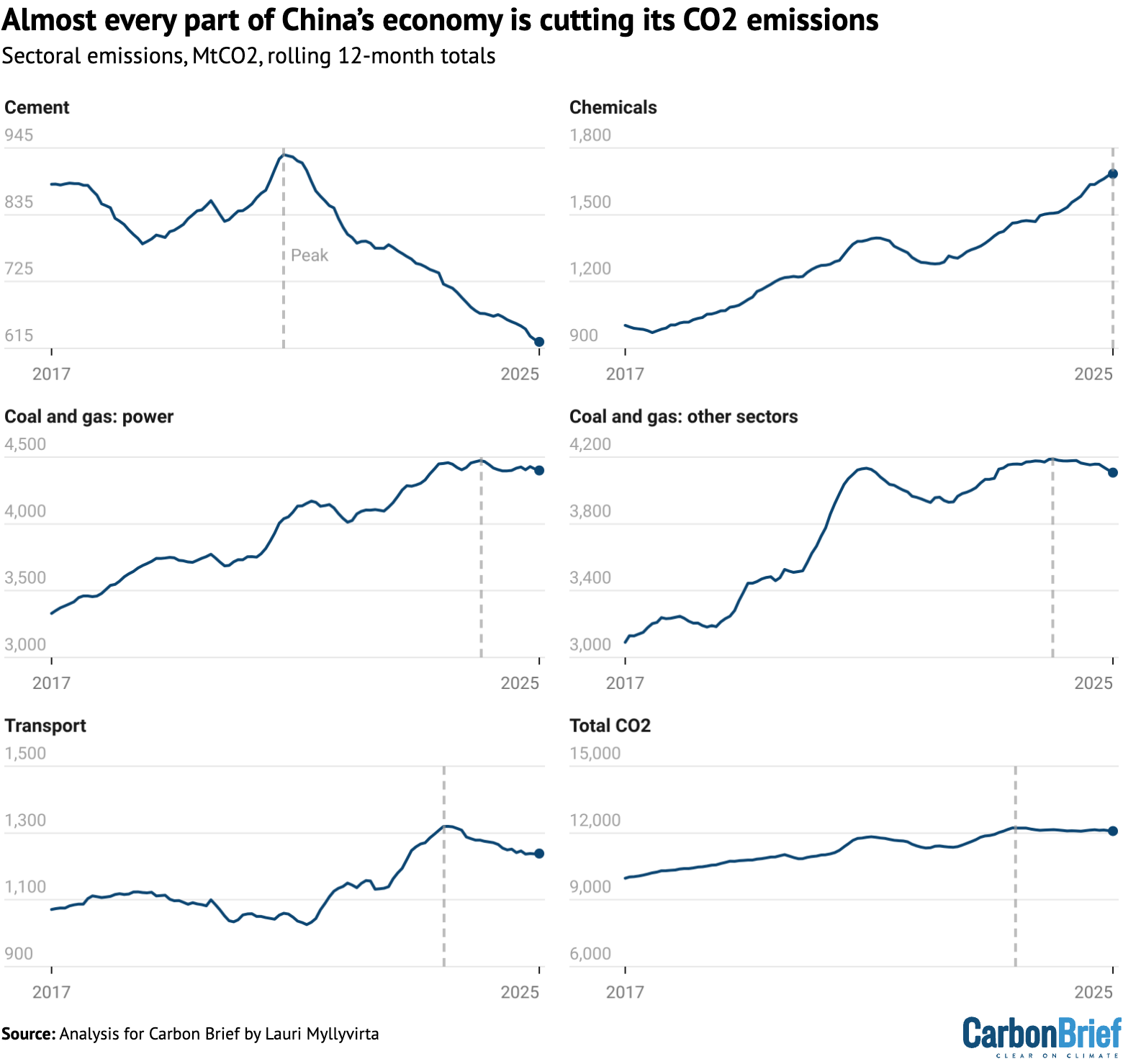

The picture continues to be finely balanced, with emissions falling in all major sectors – including transport, power, cement and metals – but rising in the chemicals industry.

This combination of factors means that emissions continue to plateau at levels slightly below the peak reached in early 2024, as shown in the figure below.

Power sector emissions fell by 1.5% year-on-year in 2025, with coal use falling 1.7% and gas use increasing 6%. Emissions from transportation fell 3% and from the production of cement and other building materials by 7%, while emissions from the metal industry fell 3%.

These declines are shown in the figure below. They were partially offset by rising coal and oil use in the chemical industry, up 15% and 10% respectively, which pushed up the sector’s CO2 emissions by 12% overall.

In other sectors – largely other industrial areas and building heat – gas use increased by 2%, more than offsetting the reduction in emissions from a 3% drop in their coal consumption.

Clean power covers electricity demand growth

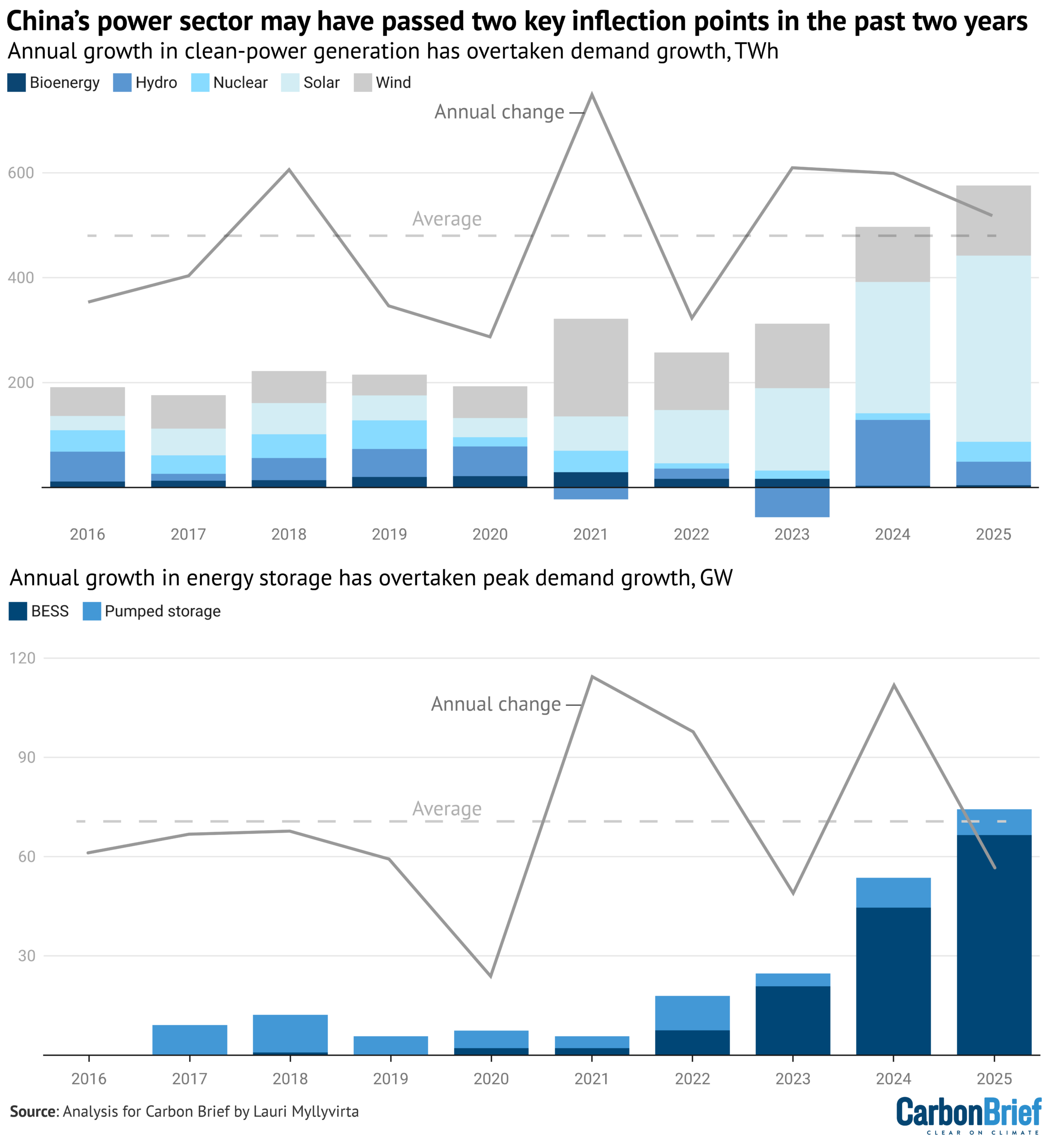

In the power sector, which is China’s largest emitter by far, electricity demand grew by 520 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2025.

At the same time, power generation from solar increased by 43% and wind power generation by 14%, delivering 360TWh and 130TWh of additional clean electricity. Nuclear power generation grew 8%, supplying another 40TWh. The increased generation from these three sources – some 530TWh – therefore met all of the growth in demand.

Hydropower generation also increased by 3% and bioenergy by 3%, helping push power generation from fossil fuels down by 1%. Gas-fired power generation increased by 6% and, as a result, power generation from coal fell by 1.9%.

Furthermore, the surge in additions of new wind and solar capacity at the end of 2025 will only show up as increased clean-power generation in 2026.

On the other hand, the growth in solar and wind power generation has fallen short of the growth in capacity, implying a fall in capacity utilisation – a measure of actual output relative to the maximum possible. This is highly likely due to increased, unreported curtailment, where wind and solar sites are switched off because the electricity grid is congested.

If these grid issues are resolved over the next few years, then generation from existing wind and solar capacity will increase over time.

Developments in 2025 extended the trend of clean-power generation growing faster than power demand overall, as shown in the top figure below. This trend started in 2023 and is the key reason why China’s emissions have been stable or falling since early 2024.

In addition, 2025 saw another potential inflection point, shown in the bottom figure below. It was the first year ever that energy storage capacity – mainly batteries – grew faster than peak electricity demand in 2025 and faster than the average growth in the past decade.

China’s energy storage capacity increased by 75GW year-on-year in 2025, while peak demand only increased by 55GW. The rise in storage capacity in 2025 is also larger than the three-year average increase in peak loads, some 72GW per year.

Peak demand growth matters, because power systems have to be designed to reliably provide enough electricity supply at the moment of highest demand.

Moreover, the increase in peak loads is a key driver of continued additions of coal and gas-fired power plants, which reached the highest level in a decade in 2025.

The growth in energy storage could provide China with an alternative way to meet peak loads without relying on increased fossil fuel-based capacity.

The growth in storage capacity is set to continue after a new policy issued by China’s top economic planner the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) in January.

This policy means energy storage sites will be supported by so-called “capacity payments”, which to date have only been available to coal- and gas-fired power plants and pumped hydro storage.

Concerns about having sufficient “firm” power capacity in the grid – that which can be turned on at will – led the government to promote new coal and gas-fired power projects in recent years, leading to the largest fossil-fuel based capacity additions in a decade in 2025, with another 290GW of coal-fired capacity still under construction.

Reforming the power system and increasing storage capacity would enable the grid to accommodate much higher shares of solar and wind, while reducing the need for new coal or gas capacity to meet rising peaks in demand.

This would both unlock more clean-power generation from existing capacity and improve the economics and risk profiles of new projects, stimulating more growth in capacity.

Peaking power CO2 requires more clean-energy growth

China’s key climate commitments for the next five-year period until 2030 are to peak CO2 emissions and to reduce carbon intensity by more than 65% from 2005 levels. The latter target requires limiting CO2 emissions at or below their 2025 level in 2030.

The record clean-energy additions in 2023-25 have barely sufficed to stabilise power-sector emissions, showing that if rapid growth in power demand continues, meeting the 2030 targets requires keeping clean-energy additions close to 2025 levels over the next five years.

China’s central government continues to telegraph a much lower level of ambition, with the NDRC setting a target of “around” 30% of power generation in 2030 coming from solar and wind, up from around 22% in 2025.

If electricity demand grows in line with the State Grid forecast of 5.6% per year, then limiting the share of wind and solar to 30% would leave space for fossil-fuel generation to grow at 3% per year from 2025 to 2030, even after increases from nuclear and hydropower.

Such an increase would mean missing China’s Paris commitments for 2030.

Alternatively, in order to meet the forecast increase in electricity demand without increasing generation from fossil fuels would require wind and solar’s share to reach 37% in 2030.

Similarly, China’s target of a non-fossil energy share of 25% in 2030 will not be sufficient to meet its carbon-intensity reduction commitment for 2030, unless energy demand growth slows down sharply.

This target is unlikely to be upgraded, since it is already enshrined in China’s Paris Agreement pledge, so in practice the target would need to be substantially overachieved if the country is to meet its other commitments.

If energy demand growth continues at the 2025 rate and the share of non-fossil energy only rises from 22% in 2025 to 25% in 2030, then the consumption of fossil fuels would increase by 3% per year, with a similar rise in CO2 emissions.

Still, another recent sign that clean-energy growth could keep exceeding government targets came in early February when the China Electricity Council projected solar and wind capacity additions of more than 300GW in 2026 – well beyond the government goal of “over 200GW”.

Chemical industry

The only significant source of growth in CO2 emissions in 2025 was the chemical industry, with sharp increases in the consumption of both coal and oil.

This is shown in the figure below, which illustrates how CO2 emissions appear to have peaked from cement production, transport, the power sector and others, whereas the chemicals industry is posting strong increases.

Even though chemical-industry emissions are small relative to other sectors – at roughly 13% of China’s total – the pace of expansion is creating an outsize impact.

Without the increase from the chemicals sector, China’s total CO2 emissions would have fallen by an estimated 2%, instead of the 0.3% reported here.

Without changes to policy, emission growth is set to continue, as the coal-to-chemicals industry is planning major increases in capacity.

Whether these expansion plans receive backing in the upcoming five-year plan for 2026-30 will have a major impact on China’s emission trends.

Another key factor is the development of oil and gas prices. Production in the coal-based chemical industry is only profitable when coal is significantly cheaper than crude oil.

The current coal-to-chemicals capacity in China is dominated by plants producing higher-value – and therefore less price-sensitive – chemicals such as olefins and aromatics, as feedstocks for the production of plastics.

In contrast, the planned expansion of the sector is expected to be largely driven by plants producing oil products and synthetic gas to be used for energy. For these products, electrification and clean-electricity generation provide a direct alternative, meaning they are even more sensitive to low oil and gas prices than chemicals production.

Outlook for China’s emissions

This is the latest analysis for Carbon Brief to show that China’s CO2 emissions have now been stable or falling for seven quarters or 21 months, marking the first such streak on record that has not been associated with a slowdown in energy demand growth.

Notably, while emissions have stabilised or begun a slow decline, there has not yet been a substantial reduction from the level reached in early 2024. This means that a small jump in emissions could see them exceed the previous peak level.

China’s official plans only call for peaking emissions shortly before 2030, which would allow for a rebound from the current plateau before the ultimate emissions peak.

If China is to meet its 2030 carbon intensity commitment – a 65% reduction on 2005 levels – then emissions would have to fall from the peak back to current levels by 2030.

Whether China’s policymakers are still committed to meeting this carbon intensity pledge, after the setbacks during the previous five-year period, is a key open question. The 2030 energy targets set to date have fallen short of what would be required.

The most important signal will be whether the top-level five-year plan for 2026-30, due in March, sets a carbon intensity target aligned with the 2030 Paris commitment.

Officially, China is sticking to the timeline of peaking CO2 emissions “before 2030”, which was announced by president Xi Jinping in 2020.

According to an authoritative explainer on the recommendations of the Central Committee of the Communist Party for the upcoming five-year plan, published by state-backed news agency Xinhua, coal consumption should “reach its peak and enter a plateau” from 2027.

It says that continued increases in demand for coal from electricity generators and the chemicals industry would be offset by reductions elsewhere. This is despite the fact that China’s coal consumption overall has already been falling for close to two years.

The reference to a “plateau” in coal consumption indicates that in official plans, meaningful absolute reductions in emissions would have to wait until after 2030. Any increase in coal consumption from 2025 to 2027, before the targeted plateau, would need to be offset by reductions in oil consumption, to meet the carbon intensity target.

Moreover, allowing coal consumption in the power sector to grow beyond the peak of overall coal use and emissions implies slowing down China’s clean-energy boom. So far, the boom has continued to exceed official targets by a wide margin.

In addition, the explainer’s expectation of further growth in coal use by the chemicals industry indicates a green light for at least a part of its sizable expansion plans.

The Xinhua article recognises that oil product consumption has already peaked, but says that oil use in the chemicals industry has kept growing. It adds that overall oil consumption should peak in 2026.

Elsewhere, the article speaks of “vigorously” developing non-fossil energy and “actively” developing “distributed” solar, which has slowed down due to recent pricing policies.

Yet it also calls for “high-quality development” of fossil fuels and increased efforts in domestic oil and gas production, suggesting that China continues to take an “all of the above” approach to energy policy.

The outcome of all this depends on how things turn out in reality. The past few years show it is possible that clean energy will continue to overperform its targets, preventing growth in energy consumption from fossil fuels despite this policy support.

The key role of the clean-energy boom in driving GDP growth and investments is one key motivator for policymakers to keep the boom going, even when central targets would allow for a slowdown. It is also possible that the five-year plans of provinces and state-owned enterprises could play a key role in raising ambition, as they did in 2022.

About the data

Data for the analysis was compiled from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, National Energy Administration of China, China Electricity Council and China Customs official data releases, as well as from industry data provider WIND Information and from Sinopec, China’s largest oil refiner.

Electricity generation from wind and solar, along with thermal power breakdown by fuel, was calculated by multiplying power generating capacity at the end of each month by monthly utilisation, using data reported by China Electricity Council through Wind Financial Terminal.

Total generation from thermal power and generation from hydropower and nuclear power were taken from National Bureau of Statistics monthly releases.

Monthly utilisation data was not available for biomass, so the annual average of 52% for 2023 was applied. Power-sector coal consumption was estimated based on power generation from coal and the average heat rate of coal-fired power plants during each month, to avoid the issue with official coal consumption numbers affecting recent data.

CO2 emissions estimates are based on National Bureau of Statistics default calorific values of fuels and emissions factors from China’s latest national greenhouse gas emissions inventory, for the year 2021. The CO2 emissions factor for cement is based on annual estimates up to 2024.

For oil, apparent consumption of transport fuels – diesel, petrol and jet fuel – is taken from Sinopec quarterly results, with monthly disaggregation based on production minus net exports. The consumption of these three fuels is labeled as oil product consumption in transportation, as it is the dominant sector for their use.

Apparent consumption of other oil products is calculated from refinery throughput, with the production of the transport fuels and the net exports of other oil products subtracted. Fossil-fuel consumption includes non-energy use such as plastics, as most products are short-lived and incineration is the dominant disposal method.

The post Analysis: China’s CO2 emissions have now been ‘flat or falling’ for 21 months appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: China’s CO2 emissions have now been ‘flat or falling’ for 21 months

Climate Change

Why cutting climate journalism is a risk we can’t afford

Felix Horne is a senior expert with Climate Rights International.

When The Washington Post laid off more than 300 staff last week, including journalists who covered climate and the environment, it was more than another grim headline about the state of the media. The cuts marked the loss of expertise and sustained scrutiny at one of the world’s most influential newsrooms, at precisely the moment when the climate crisis demands more reporting, not less.

These decisions do not simply downsize a business. They weaken public understanding of how climate change impacts lives, how cause and effect connect, and how power can be held to account.

Without expertise and experience, wildfires are reported without the underlying climate context that fuels them. Energy stories lose their climate dimension. Pollution is treated as an unfortunate accident rather than a foreseeable harm from fossil fuel dependence.

The facts still exist – but fewer people are paid, protected, or empowered to surface them, and with that goes people’s understanding of how climate is intimately intertwined with our lives.

These cuts follow a broader pattern across mainstream media in the United States, Europe and beyond. In 2024 and 2025 alone, major US outlets announced thousands of job losses.

CBS, CNN, NBC and other broadcasters cut newsroom staff. The Guardian has acknowledged sustained financial strain and has reduced or consolidated reporting capacity in recent years.

Meanwhile, local newspapers, the primary source of reporting on nearby floods, heatwaves, refineries, pipelines and mines, continue to disappear. In the US, more than 3,200 local newspapers closed since 2005, leaving large parts of the US without consistent, on-the-ground reporting.

Threats and harassment

Beyond closures, climate journalists face numerous threats. Journalists covering climate and environmental issues report rising harassment, legal threats and violence, particularly when reporting on fossil fuels, mining and land conflicts. One study found that 39% of journalists and editors covering the climate crisis had been threatened because of their work.

Online abuse, often coordinated and sustained, has become a routine tool for silencing climate reporting. And this doesn’t count the many fixers, translators, drivers and other local employees who face threats because of their role in this reporting, many of whom face a further loss of their livelihood because of these cuts.

At Climate Rights International (CRI), we document climate harms and human rights abuses linked to fossil fuels, mining and deforestation, among many other subjects. But our investigations do not exist in a vacuum.

They are often strengthened, and sometimes made possible, by local journalists who first uncover these harms, and by climate reporters who amplify our findings, connect them to broader patterns, and further our investigations by focusing on new angles, ongoing efforts at accountability or updated findings over time. They are indispensable to what we do and the impact we are trying to have.

When journalism retreats, misinformation fills the gap. In the absence of trusted, verified reporting, false or misleading climate narratives spread quickly online. Confusion replaces clarity about the reality of climate change: its links to energy choices, connections with the food we eat, and the scale of action required. Urgency erodes.

Climate change becomes less politically important when it becomes less visible. What is not reported is not discussed. What is not discussed does not become an issue for most voters, and therefore for politicians. The climate crisis can be manipulated by politicians as just another issue of special interest groups to balance with other interests, rather than being treated as the existential threat it is.

Fragile progress

To be clear, progress has been made. In recent years, climate considerations have been more consistently integrated into mainstream coverage of energy, economics, and geopolitics. Energy costs, rising food costs, migration, extreme weather and supply chains are now more often reported with climate dimensions in view.

But that progress is fragile. It depends on reporters and editors with climate expertise sitting in newsrooms, able to ask the second question, to connect today’s flooding with the climate crisis, and to connect today’s energy story to tomorrow’s climate harm.

This matters profoundly for fossil fuels, deforestation and transition minerals. Who is reporting on LNG terminals, new gas fields, lithium or nickel mining, the burning and clear-cutting of remote forests, or rising energy costs determines whether these developments are understood as narrow economic stories, or as climate and human rights choices with long-term consequences.

West Africa’s first lithium mine awaits go-ahead as Ghana seeks better deal

Independent platforms, newsletters and Substack writers now produce some of the best climate coverage anywhere. They matter deeply. But they often reach audiences already paying attention to these issues. Mainstream media still plays a unique role: introducing climate realities to people who did not set out to read about climate change at all.

The erosion of climate journalism is unfolding alongside broader efforts to silence climate voices – through laws restricting protests, lawsuits aimed at stifling dissent, surveillance of activists and attacks on environmental defenders. CRI and others have documented how these tactics work together to suppress inconvenient facts.

Fewer journalists and fewer activists lead to less understanding of why climate is the story right now. The climate crisis will not pause because fewer people are paid to document it.

The question is whether societies choose to face our unfolding reality with evidence or allow silence and distortion to take its place. Supporting climate journalism is an investment in truth, accountability and a liveable planet for our children and future generations.

The post Why cutting climate journalism is a risk we can’t afford appeared first on Climate Home News.

Climate Change

Accelerated Global Warming Could Lock Earth Into a Hothouse Future

Scientists say warming is increasing faster than at any time in at least 3 million years. There is no guide for what comes next.

If you think of Earth’s climate system as a backyard swing that’s been gently swaying for millennia, then human-caused global warming is like a sudden shove strong enough to disrupt the usual arc and buckle the chains.

Accelerated Global Warming Could Lock Earth Into a Hothouse Future

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility