The amount of forest lost around the world has reduced by millions of hectares each year in recent decades, but countries are still off track to meet “important” deforestation targets.

These are the findings of the Global Forest Resources Assessment – a major new report from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization – which says that an estimated 10.9m hectares (Mha) of land was deforested each year between 2015 and 2025.

This is almost 7Mha less than the amount of annual forest loss over 1990-2000.

Since 1990, the area of forest destroyed each year has halved in South America, although it still remains the region with the highest amount of deforestation.

Europe was the only region in the world where annual forest loss has increased since 1990.

Agriculture has historically been the leading cause of deforestation around the world, but the report notes that wildfires, climate change-fuelled extreme weather, insects and diseases increasingly pose a threat.

The Global Forest Resources Assessment is published every five years. The 2025 report compiles and analyses national forest data from almost every country in the world over 1990-2025.

Carbon Brief has picked out five key findings from the report around deforestation, carbon storage and the amount of forest held within protected areas around the world.

1. Rates of deforestation are declining around the world

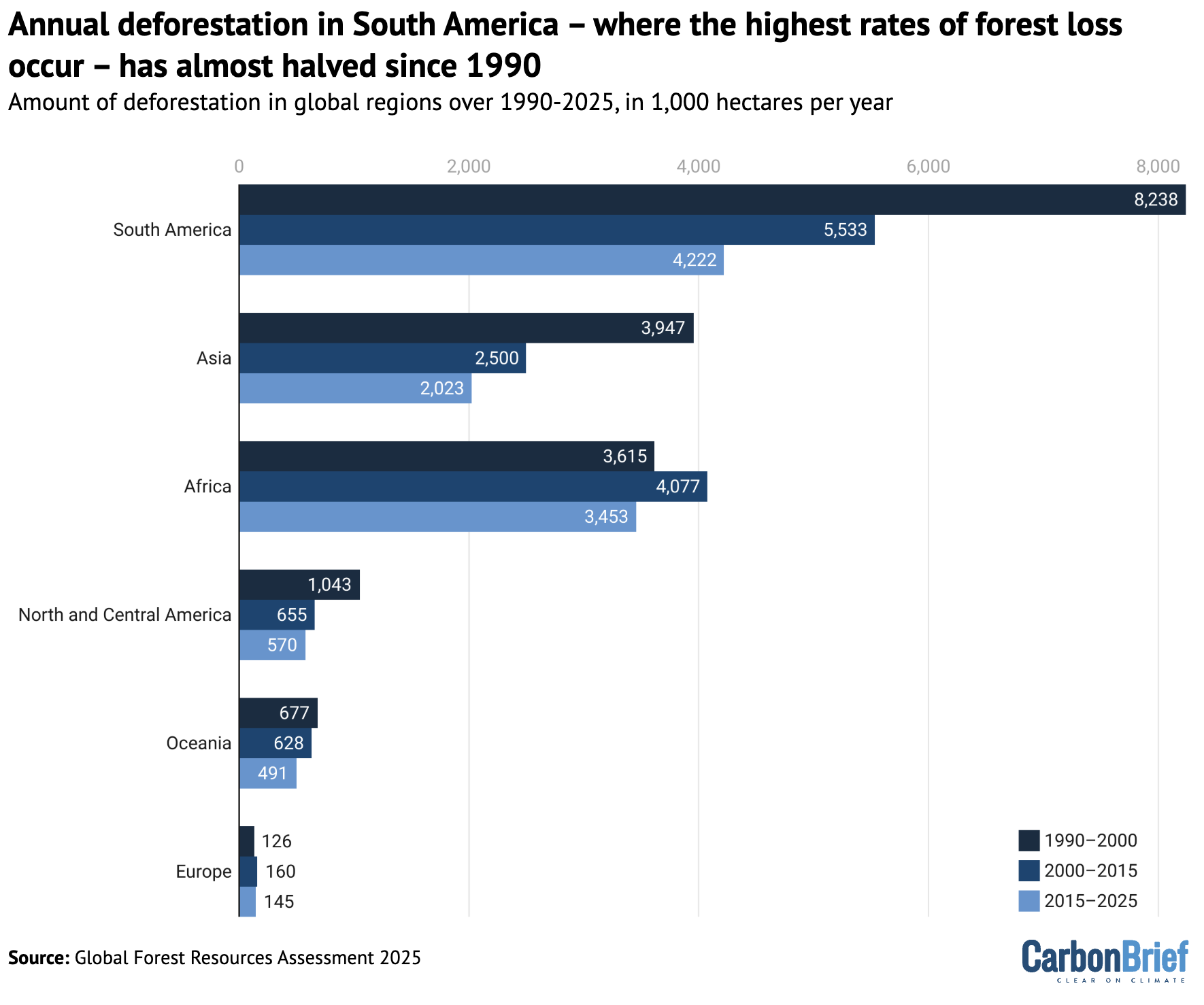

Rates of annual deforestation, in thousands of hectares, in South America, Asia, Africa, North and Central America, Oceania and Europe over 1990-2000 (dark blue), 2000-15 (medium blue) and 2015-25 (light blue). Source: Global Forest Resources Assessment 2025

In total, around 489Mha of forest have been lost due to deforestation since 1990, the new report finds. Most of this – 88% – occurred in the tropics.

This breaks down to around 10.9Mha of forest lost each year between 2015 and 2025, a reduction compared to 13.6Mha of loss over 2000-15 and 17.6Mha over 1990-2000.

Deforestation refers to the clearing of a forest, typically to repurpose the land for agriculture or use the trees for wood.

The chart above shows that South America experiences the most forest loss each year, although annual deforestation levels have halved from 8.2Mha over 1990-2000 to 4.2Mha over 2015-25.

Annual deforestation in Asia also saw a sizable reduction, from 3.9Mha over 1990-2000 to 2Mha over 2015-25, the report says.

Europe had the lowest overall deforestation rates, but was also the only region to record an increase over the last 35 years, with deforestation rates growing from 126,000 hectares over 1990-2000 to 145,000 hectares in the past 10 years.

Despite the downward global trend, FAO chief Dr Qu Dongyu notes in the report’s foreword that the “world is not on track to meet important global forest targets”.

In 2021, more than 100 countries pledged to halt and reverse global deforestation by 2030. But deforestation rates in 2024 were 63% higher than the trajectory needed to meet this 2030 target, according to a recent report from civil society groups.

The goals of this pledge were formally recognised in a key text at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai in 2023, which “emphasise[d]” that halting and reversing deforestation and forest degradation by 2030 would be key to meeting climate goals.

2. Global net forest loss has more than halved since 1990

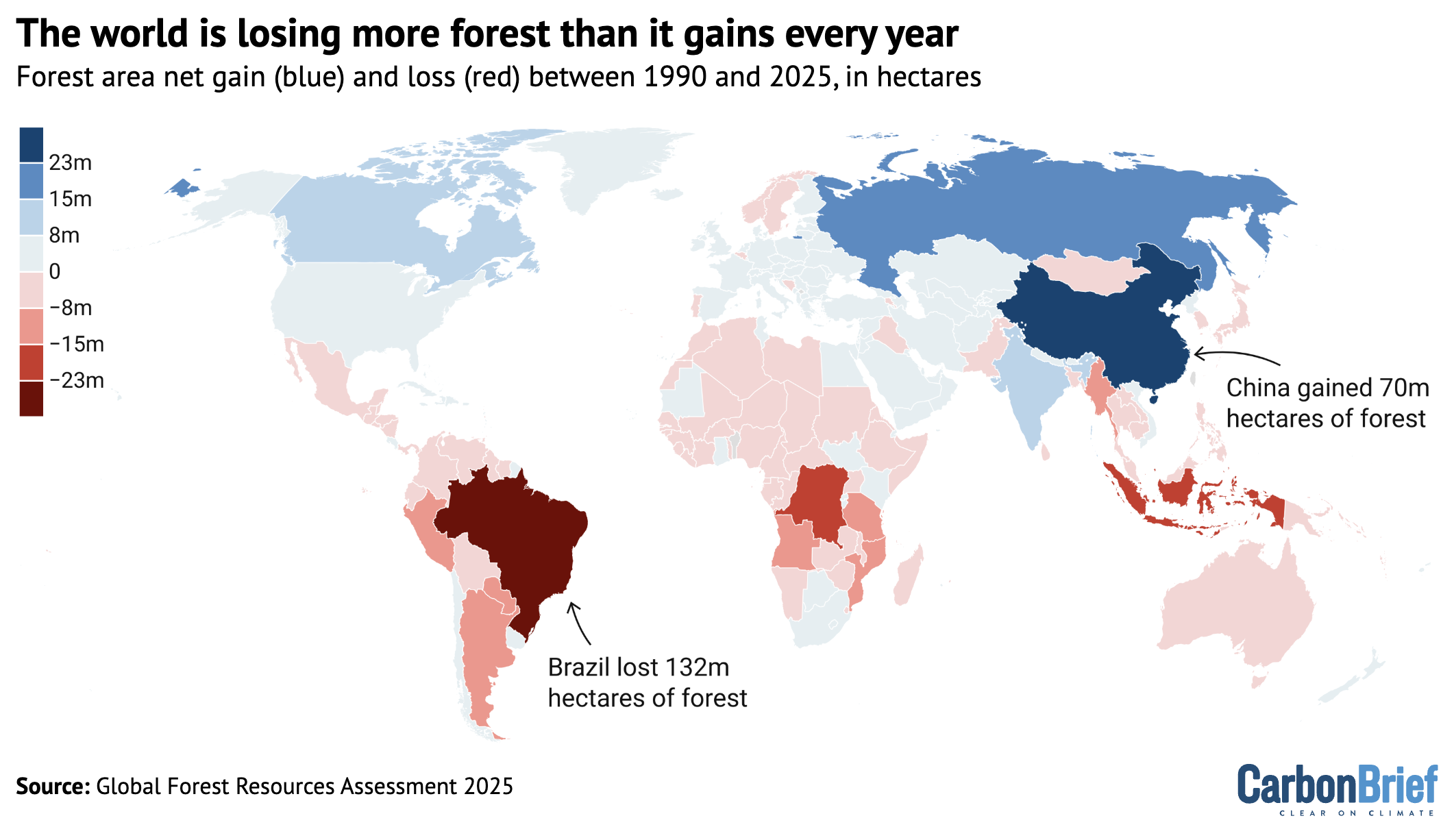

Forest area net change by country between 1990 and 2025, in hectares. Source: Global Forest Resources Assessment 2025

The new report finds that forests cover more than 4bn hectares of land, an area encompassing one-third of the planet’s land surface.

More than half of the world’s forested area is located in just five countries: Russia, Brazil, Canada, the US and China.

The map above shows that, overall, more forest is lost than gained each year around the world. There was 6.8Mha of forest growth over 2015-25, but 10.9Mha of forest lost.

The annual rate of this global net forest loss – the amount that deforestation has exceeded the amount regrown – has more than halved since 1990, dropping from 10.7Mha over 1990-2000 to 4.1Mha over 2015-25.

The report says this change was due to reduced deforestation in some countries and increased forest expansion in others. However, the rate of forest expansion has also slowed over time – from 9.9Mha per year in 2000-15 to 6.8Mha per year in 2015-25.

There are many driving factors behind continuing deforestation. Agriculture has historically been the leading cause of forest loss, but wildfire is increasingly posing a threat. Wildfires were the leading driver of tropical forest loss in 2024 for the first time on record, a Global Forest Watch report found earlier this year.

The new UN report says that an average of 261Mha of land was burned by fire each year over 2007-19. Around half of this area was forest. Around 80% of the forested land impacted by fires in 2019 was in the subtropics – areas located just outside tropical regions, such as parts of Argentina, the US and Australia.

The report notes that fire is widely used in land management practices, but uncontrolled fires can have “major negative impacts on people, ecosystems and climate”.

It adds that researchers gathered information on fires up as far as 2023, but chose to focus on 2007-19 due to a lack of more recent data for some countries.

A different report from an international team of scientists recently found that fires burned at least 370Mha of land – an area larger than India – between March 2024 and February 2025.

3. Many countries are hugely increasing their forest area

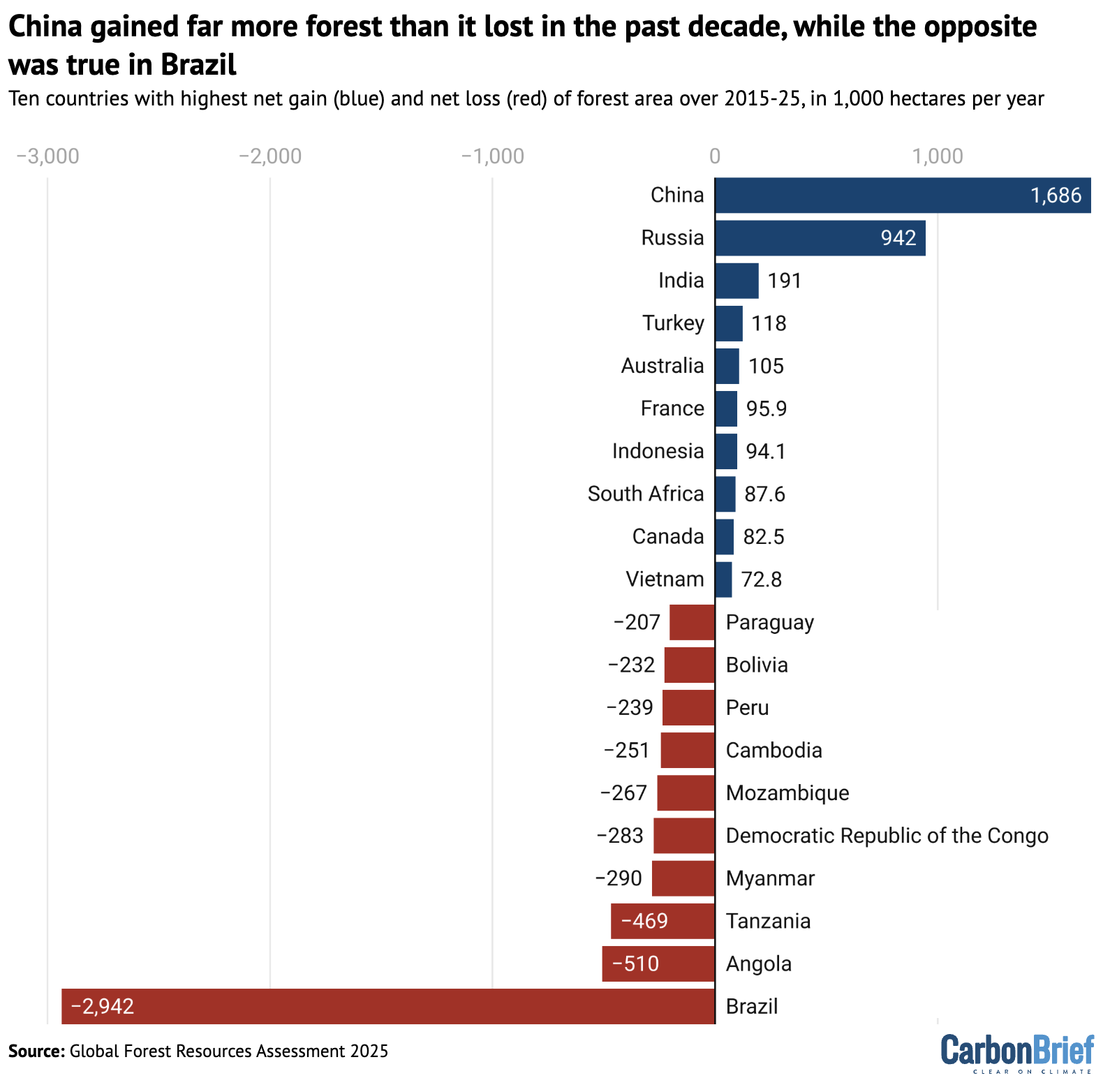

Top 10 countries for annual net gain (blue) and net loss (red) of forest area over 2015-25, in 1,000 hectares per year. Source: Global Forest Resources Assessment 2025

Globally, deforestation is declining, but the trend varies from country to country.

The chart above shows that some nations, such as China and Russia, added a lot more forest cover than they removed in the past decade through, for example, afforestation programmes.

But in other countries – particularly Brazil – the level of deforestation far surpasses the amount of forest re-grown.

Deforestation in Brazil dropped by almost one-third between 2023 and 2024, news outlet Brasil de Fato reported earlier this year, which was during the time Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took over as president. The new UN report finds that, on average, Brazil lost 2.9Mha of forest area each year over 2015-25, compared to 5.8Mha over 1990-2000.

Russia’s net gain of forest cover increased significantly since 1990 – growing from 80,400ha per year in 1990-2000 to 942,000ha per year in 2015-25.

In China, although it is also planting significant levels of forest, the forest level gained has dropped over time, from 2.2Mha per year in 2000-15 to 1.7Mha per year in 2015-25.

Levels of net forest gain in Canada also fell from 513,000ha per year in 2000-15 to 82,500ha per year in 2015-25.

In the US, the net forest growth trend reversed over the past decade – from 437,000ha per year of gain in 2000-15 to a net forest loss of 120,000ha per year from 2015 to 2025.

Oceania reversed a previously negative trend to gain 140,000ha of forests per year in the past decade, the report says. This was mainly due to changes in Australia, where previous losses of tens of thousands of hectares each year turned into an annual net gain of 105,000ha each year by 2015-25.

4. The world’s forests hold more than 700bn tonnes of carbon

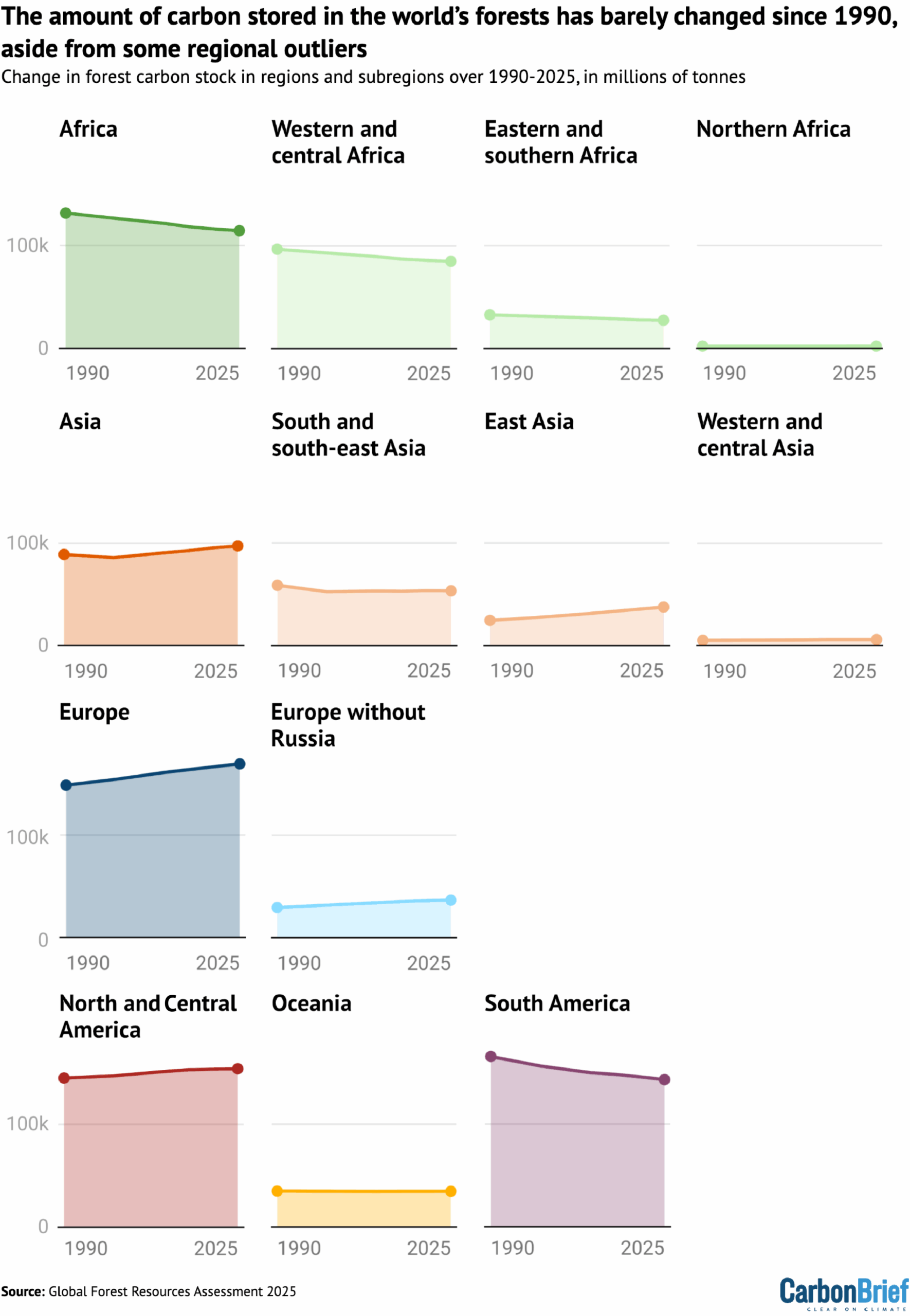

Changes in forest carbon stock by region and subregion of the world over 1990-2025. Source: Global Forest Resources Assessment 2025

The “carbon stock” of a forest refers to how much carbon is stored in its trees and soils. Forests are among the planet’s major carbon sinks.

The new report estimates that forests stored an estimated 714bn tonnes, or gigatonnes, of carbon (GtC) in 2025.

Europe (including Russia) and the Americas account for two-thirds of the world’s total forest carbon storage.

The global forest carbon stock decreased from 716GtC to 706GtC between 1990 and 2000, before growing slightly again by 2025. The report mainly attributes this recent increase to forest growth in Asia and Europe.

The report notes that the total amount of carbon stored in forests has remained largely static over the past 35 years, but with some regional differences, as highlighted in the chart above.

The amount of carbon stored in forests across east Asia, Europe and North America is “significantly higher” now due to expanded forest areas, but it is lower in South America, Africa and Central America.

Several studies have shown that there are limitations on the ability of forests to keep absorbing CO2, with difficulties posed by hotter, drier weather fuelled by climate change.

A 2024 study found that record heat in 2023 negatively impacted the ability of land and ocean sinks to absorb carbon – and that the global land sink was at its weakest since 2003.

Another study, published in 2022, said that drying and warming as a result of deforestation reduces the carbon storage ability of tropical forests, especially in the Congo basin and the Amazon rainforest.

5. Around one-fifth of the world’s forests are located in protected areas

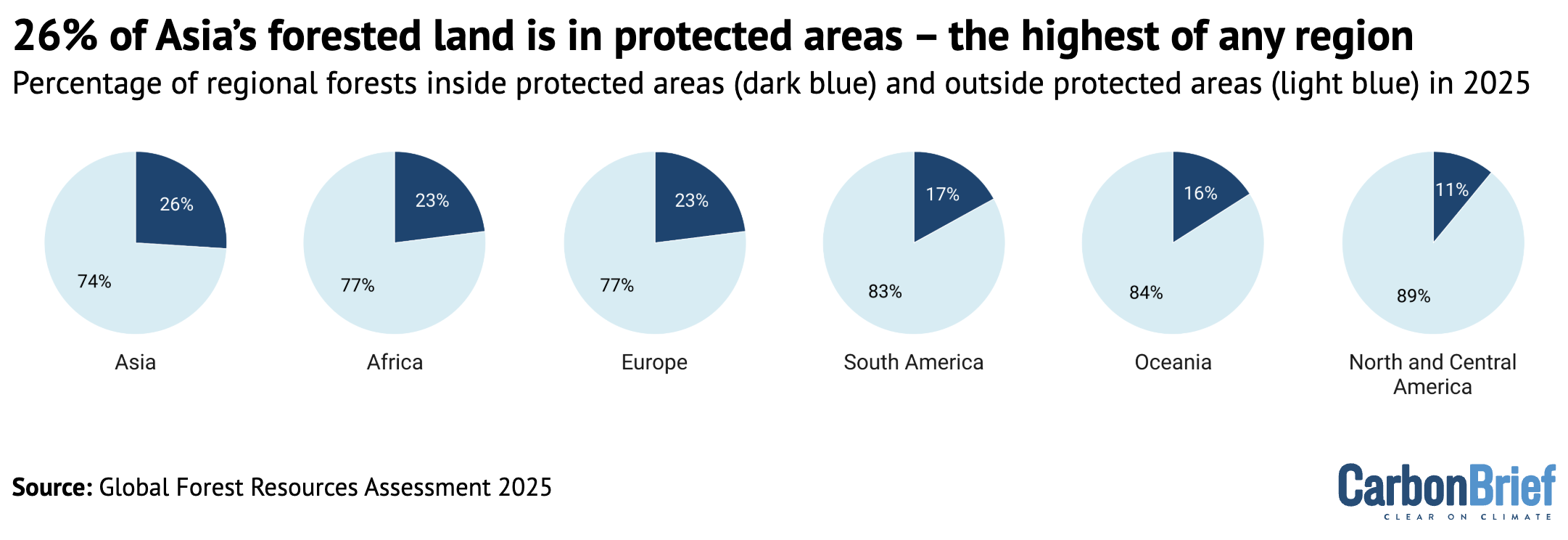

The percentage of forest land in Asia, Africa, Europe, South America, Oceania and North and Central America contained inside protected areas (dark blue) and outside protected areas (light blue) in 2025. Source: Global Forest Resources Assessment 2025

The amount of forested land located in protected areas increased across all regions between 1990 and 2025.

For an area to be considered “protected”, it must be managed in a way that conserves nature.

Around 20% of the world’s forests are located in these protected areas, the new report finds, which amounts to 813Mha of land – an area almost the size of Brazil.

Nearly every country in the world has pledged to protect 30% of the Earth’s land and sea by 2030. However, more than half of countries have not committed to this target on a national basis, Carbon Brief analysis showed earlier this year.

Almost 18% of land and around 8% of the ocean are currently in protected areas, a UN report found last year. The level is increasing, the report said, but considerable progress is still needed to reach the 2030 goal.

The new UN report notes that Europe, including Russia, holds 235Mha of protected forest area, which is the largest of any region and accounts for 23% of the continent’s total forested land.

As highlighted in the chart above, 26% of all forests in Asia are protected, which is the highest of any region. The report notes that this is largely due to a vast amount of protected forested land in Indonesia.

Three countries and one island territory reported that upwards of 90% of their forests are protected – Norfolk Island, Saudi Arabia, Cook Islands and Uzbekistan.

The post UN report: Five charts showing how global deforestation is declining appeared first on Carbon Brief.

UN report: Five charts showing how global deforestation is declining

Climate Change

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of America’s Broken Health Care System

American farmers are drowning in health insurance costs, while their German counterparts never worry about medical bills. The difference may help determine which country’s small farms are better prepared for a changing climate.

Samantha Kemnah looked out the foggy window of her home in New Berlin, New York, at the 150-acre dairy farm she and her husband, Chris, bought last year. This winter, an unprecedented cold front brought snowstorms and ice to the region.

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of the Broken U.S. Health Care System

Climate Change

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Two Utah Congress members have introduced a resolution that could end protections for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Conservation groups worry similar maneuvers on other federal lands will follow.

Lawmakers from Utah have commandeered an obscure law to unravel protections for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, potentially delivering on a Trump administration goal of undoing protections for public conservation lands across the country.

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Climate Change

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

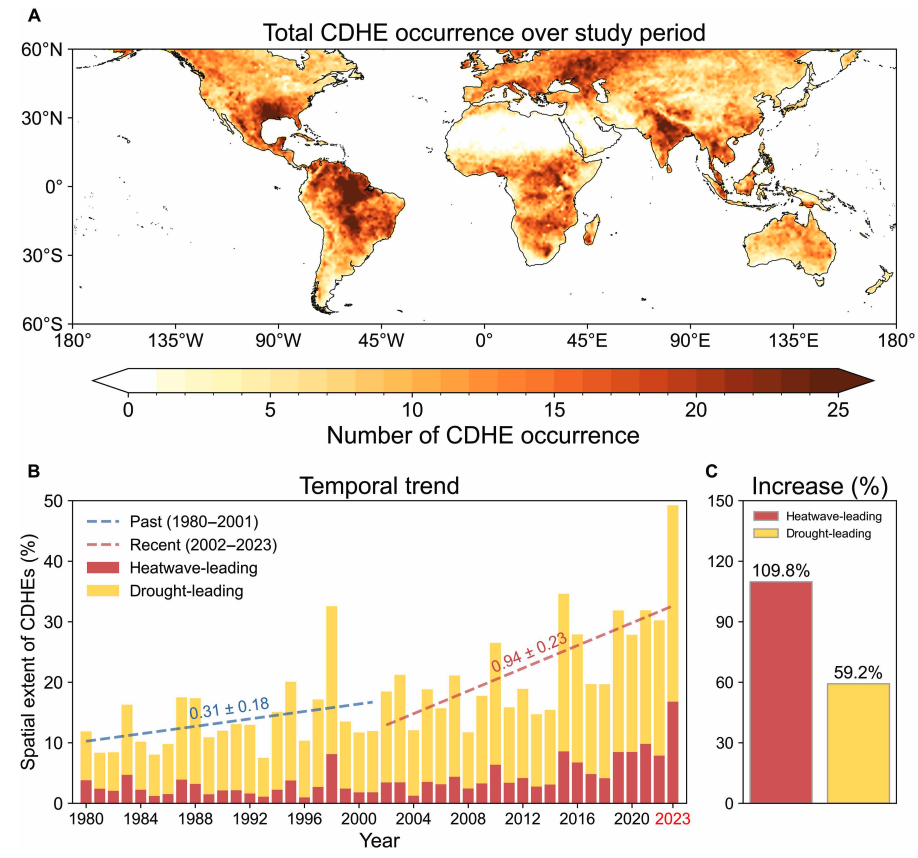

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits