More than half of countries have not committed to protecting 30% of their land and sea for nature by 2030 in plans submitted to the UN – despite signing a global agreement to do so less than three years ago, a Carbon Brief and Guardian investigation can reveal.

In December 2022, nearly all nations agreed to protect “30% of Earth’s land and sea for nature” by the end of the decade. This commitment – referred to as “30 by 30” – is the flagship target of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), often likened to the “Paris Agreement for nature”.

But, 70 out of the 137 (51%) countries that have submitted UN plans outlining how they will meet the targets of the GBF do not commit to “30 by 30” within their borders, according to analysis of these documents by Carbon Brief and the Guardian.

Instead, these countries either pledge to protect a lower percentage of their territory for nature or fail to explicitly commit to a numerical target at all.

Countries failing to commit to “30 by 30” in UN plans represent just over one-third of Earth’s land surface, the analysis shows.

The list includes some of the most nature-rich nations on Earth, such as Indonesia, Peru and South Africa, along with developed countries such as Finland, Norway and Switzerland.

Speaking to Carbon Brief and the Guardian, one nation said that meeting “30 by 30” within its borders would be “extremely challenging” to achieve, while another said that developing countries in particular should not face an “unnecessarily heavy burden” in reaching the global goal.

The investigation shows that “many countries have not been ambitious enough with their domestic conservation commitments and, as a result, we are collectively not currently on track to meet the global 30 by 30 target”, one expert said.

A third of Earth

At the COP15 nature summit in 2022, countries agreed to the GBF, a broad set of targets and goals with an overall aim to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030.

Target 3 of the GBF – which says countries should ensure “at least” 30% of Earth is in protected areas or governed by other conservation measures by 2030 (“30 by 30”) – is considered by many to be the flagship aim of the agreement and has been likened to the 1.5C temperature goal of the Paris Agreement in articles and speeches stressing its importance.

All countries were asked to submit plans to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity outlining how they will meet the targets of the GBF within their territories ahead of the COP16 nature summit in 2024. These are called national biodiversity strategies and action plans, or “NBSAPs”.

A separate Carbon Brief and Guardian investigation last October found that 85% of countries missed the deadline to submit their NBSAPs, with some arguing that the deadline was too challenging or that they were not able to access funds to help prepare their documents.

Countries unable to produce their NBSAPs were asked to instead submit national targets to the UN. These are simple lists of targets that countries will aim for without an accompanying plan of action.

As of 24 February 2025, 44 countries and the EU had submitted NBSAPs to the UN, while 124 parties had submitted national targets. (As some countries submitted both national targets and NBSAPs, it means that, overall, 137 countries have put forward a plan of some kind.)

To investigate whether countries have committed to the “30 by 30” pledge within their borders in these plans, Carbon Brief and the Guardian analysed the full text of each NBSAP, as well as any target that had been tagged as relating to target 3 of the GBF.

The analysis finds that, of 137 countries that have submitted plans to the CBD, more than half – 70 countries, or 51% – do not commit to protecting 30% of their land and sea by 2030.

Of these, 21 countries did not supply a numerical target for protecting their land area, 26 set targets for land protection that were less than 30% and eight set land targets of or greater than 30%, but sea-protection targets less than 30%.

Of the remaining countries, 13 did not submit any targets relating to coverage of protected areas. Two others set goals further in the future than 2030.

A further 10 countries, or 7%, do not make it clear from the plans that they submitted whether or not they have a pledge that meets the conditions of 30 by 30. This includes: countries that specify that they will protect 30% of “areas of particular importance”; countries that gave a target for improvement, but did not provide a baseline; and countries that submitted only one or two targets.

Just 42% of countries – 57 in total – commit to protecting 30% of both land and sea by 2030.

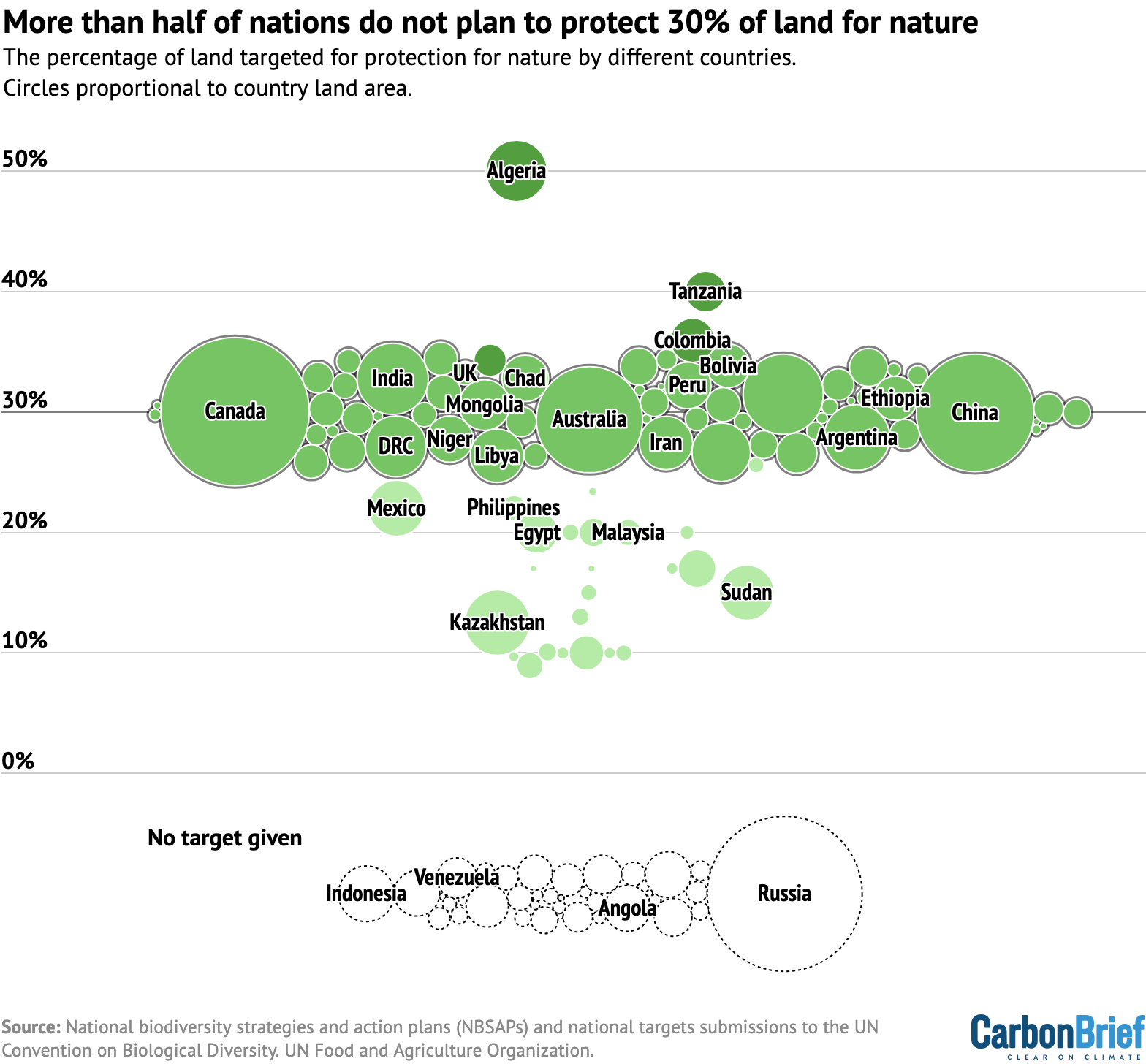

The chart below shows the countries that have submitted NBSAPs and/or national targets to the UN. On the chart, countries are clustered by the percentage of land they have pledged to protect and the size of each bubble represents their land area. (Countries clustered around the 30% line and outlined in grey all have pledges to protect 30% of land area.)

Countries clustered below “no target” are those that have not pledged a numerical target for protecting their land or those who have produced a plan, but have not included a protected area target.

The analysis shows that, collectively, more than one-third of the Earth’s land area is covered by a pledge that does not fulfil the “30 by 30” target, while around half is covered by a “30 by 30” pledge.

Seven of the 17 “megadiverse” countries – which together provide a home to 70% of the world’s biodiversity – have not committed to 30 by 30, the analysis finds. This includes Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, the Philippines, South Africa and Venezuela.

A further 61 countries have not submitted an NBSAP or national targets and so have not been assessed in the analysis. This includes the world’s most biodiverse nation, Brazil.

The figures also do not include the US, which – although a megadiverse country – is not party to the CBD and, therefore, is not subject to the goals and targets of the GBF.

Former US president Joe Biden committed the country to the “30 by 30” pledge. However, the “Project 2025” policy blueprint – which Donald Trump is largely following – calls for the target to be scrapped.

The EU submitted an NBSAP that covers its 27 member states and commits to 30 by 30.

However, individual countries are also party to the CBD and are expected to submit their own national plans. For the purposes of this analysis, EU member states were only considered to be meeting “30 by 30” if they submitted their own NBSAP or national target that did so.

‘Extremely challenging’

Carbon Brief and the Guardian reached out to megadiverse countries and developed nations to ask why they had chosen not to commit to “30 by 30” in their UN plans.

Indonesia, a megadiverse country that is home to the world’s third-largest rainforest, did not give a numerical target for how much of its territory it is able to protect for nature in its NBSAP.

A government spokesperson says that it is Indonesia’s view that “it is not essential to explicitly state that the 30% protection target is for terrestrial and marine areas” in its territory, explaining:

“Indonesia is of the view that all of us need to understand that the GBF is indeed global. And, by being global, it is natural that this framework should be implemented globally and collectively, without putting an unnecessarily heavy burden on some of us.

“Indonesia is committed to ambitious yet practical targets for the GBF, with an emphasis on the fact that not all parties are at the same level if targets are assessed numerically.”

The spokesperson adds that “managing biodiversity is not an easy task” and that the “balance of economic, social and environmental aspects must be maintained, particularly for developing countries like Indonesia”.

In its NBSAP, megadiverse nation Mexico commits to protecting 30% of its oceans, but only 22% of its land.

Dr Andrea Cruz Angón, coordinator of biodiversity strategies and policies at Conabio, the federal government’s biodiversity commission, says that the targets are still “being reviewed and adjusted” by the appropriate federal agencies.

She adds that the targets were produced after workshops were held “with subnational governments, youth, Indigenous peoples and Afro-Mexican communities” to identify “barriers and opportunities for these actors to make voluntary commitments to the targets”.

Finland, one of the EU’s member states, has not yet released an NBSAP, but submitted its national targets for meeting the goals of the GBF to the UN in August 2024. In these plans, Finland does not commit to “30 by 30”.

A spokesperson for the Finnish government says it was still preparing its NBSAP and, as a result, none of its targets are final, but adds:

“Achieving a 30% increase in protected area by 2030 would be extremely challenging, as to reach this target, for example, the protected area in land areas would have to increase by about over 700,000 hectares per year.”

In its NBSAP, Norway committed to protecting 30% of its land for nature by 2030 – but says it was still assessing its ocean protection target and “will come back with a plan for how a future goal can be achieved in a way that also facilitates the sustainable use of Norwegian marine areas”.

A spokesperson for Norway says the nation is “committed to contribute towards the 30 by 30 target”, adding:

“A national conservation target for Norwegian sea areas has not yet been concluded. This is due to an ongoing national process to assess which marine areas that can be recognised as protected through ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ (OECM), in accordance with [UN biodiversity] criteria.

“The conclusion of this process will clarify the current conservation status of Norwegian waters, and consequently enable us to set a national target.”

‘Go back to the drawing board’

Inger Andersen, executive director of the UN Environment Programme, tells Carbon Brief and the Guardian that “30 by 30” is a “global target and how countries take that on board at the national level will be different across the world, depending on national circumstances”.

She points to the Protected Planet Report 2024, which shows that only 17.6% of land and 8.4% of the ocean is currently being conserved for nature – with just five years to go until the “30 by 30” deadline, adding:

“As the world faces a nature and biodiversity loss crisis, it is clear we must go much further, much faster. This will not be possible without financial, technical and capacity support for many countries.”

Responding to Carbon Brief and the Guardian’s investigation, Brian O’Donnell, director of the Campaign for Nature, a group advocating for the 30 by 30 target, says:

“Many countries have not been ambitious enough with their domestic conservation commitments and, as a result, we are collectively not currently on track to meet the global ‘30 by 30’ target. This is troubling and action must be taken to put the world on track.”

To get on track for “30 by 30”, developed nations must “directly fund” the target to enable developing countries to protect more of their territories for nature, he says, adding that the “30 by 30” pledge also needs to be championed at a higher level by global leaders and the UN.

He adds that countries not committing to “30 by 30” in their UN plans “should go back to the drawing board and update their plans with ones in which conservation is commensurate with the challenge of biodiversity loss and the needs of communities”.

The full Carbon Brief and Guardian analysis can be found here.

The post Revealed: More than half of nations fail to protect 30% of land and sea in UN nature plans appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Revealed: More than half of nations fail to protect 30% of land and sea in UN nature plans

Climate Change

For proof of the energy transition’s resilience, look at what it’s up against

Al-Karim Govindji is the global head of public affairs for energy systems at DNV, an independent assurance and risk management provider, operating in more than 100 countries.

Optimism that this year may be less eventful than those that have preceded it have already been dealt a big blow – and we’re just weeks into 2026. Events in Venezuela, protests in Iran and a potential diplomatic crisis over Greenland all spell a continuation of the unpredictability that has now become the norm.

As is so often the case, it is impossible to separate energy and the industry that provides it from the geopolitical incidents shaping the future. Increasingly we hear the phrase ‘the past is a foreign country’, but for those working in oil and gas, offshore wind, and everything in between, this sentiment rings truer every day. More than 10 years on from the signing of the Paris Agreement, the sector and the world around it is unrecognisable.

The decade has, to date, been defined by a gritty reality – geopolitical friction, trade barriers and shifting domestic priorities – and amidst policy reversals in major economies, it is tempting to conclude that the transition is stalling.

Truth, however, is so often found in the numbers – and DNV’s Energy Transition Outlook 2025 should act as a tonic for those feeling downhearted about the state of play.

While the transition is becoming more fragmented and slower than required, it is being propelled by a new, powerful logic found at the intersection between national energy security and unbeatable renewable economics.

A diverging global trajectory

The transition is no longer a single, uniform movement; rather, we are seeing a widening “execution gap” between mature technologies and those still finding their feet. Driven by China’s massive industrial scaling, solar PV, onshore wind and battery storage have reached a price point where they are virtually unstoppable.

These variable renewables are projected to account for 32% of global power by 2030, surging to over half of the world’s electricity by 2040. This shift signals the end of coal and gas dominance, with the fossil fuel share of the power sector expected to collapse from 59% today to just 4% by 2060.

Conversely, technologies that require heavy subsidies or consistent long-term policy, the likes of hydrogen derivatives (ammonia and methanol), floating wind and carbon capture, are struggling to gain traction.

Our forecast for hydrogen’s share in the 2050 energy mix has been downgraded from 4.8% to 3.5% over the last three years, as large-scale commercialisation for these “hard-to-abate” solutions is pushed back into the 2040s.

Regional friction and the security paradigm

Policy volatility remains a significant risk to transition timelines across the globe, most notably in North America. Recently we have seen the US pivot its policy to favour fossil fuel promotion, something that is only likely to increase under the current administration.

Invariably this creates measurable drag, with our research suggesting the region will emit 500-1,000 Mt more CO₂ annually through 2050 than previously projected.

China, conversely, continues to shatter energy transition records, installing over half of the world’s solar and 60% of its wind capacity.

In Europe and Asia, energy policy is increasingly viewed through the lens of sovereignty; renewables are no longer just ‘green’, they are ‘domestic’, ‘indigenous’, ‘homegrown’. They offer a way to reduce reliance on volatile international fuel markets and protect industrial competitiveness.

Grids and the AI variable

As we move toward a future where electricity’s share of energy demand doubles to 43% by 2060, we are hitting a physical wall, namely the power grid.

In Europe, this ‘gridlock’ is already a much-discussed issue and without faster infrastructure expansion, wind and solar deployment will be constrained by 8% and 16% respectively by 2035.

Comment: To break its coal habit, China should look to California’s progress on batteries

This pressure is compounded by the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI). While AI will represent only 3% of global electricity use by 2040, its concentration in North American data centres means it will consume a staggering 12% of the region’s power demand.

This localized hunger for power threatens to slow the retirement of fossil fuel plants as utilities struggle to meet surging base-load requirements.

The offshore resurgence

Despite recent headlines regarding supply chain inflation and project cancellations, the long-term outlook for offshore energy remains robust.

We anticipate a strong resurgence post-2030 as costs stabilise and supply chains mature, positioning offshore wind as a central pillar of energy-secure systems.

Governments defend clean energy transition as US snubs renewables agency

A new trend is also emerging in behind-the-meter offshore power, where hybrid floating platforms that combine wind and solar will power subsea operations and maritime hubs, effectively bypassing grid bottlenecks while decarbonising oil and gas infrastructure.

2.2C – a reality check

Global CO₂ emissions are finally expected to have peaked in 2025, but the descent will be gradual.

On our current path, the 1.5C carbon budget will be exhausted by 2029, leading the world toward 2.2C of warming by the end of the century.

Still, the transition is not failing – but it is changing shape, moving away from a policy-led “green dream” toward a market-led “industrial reality”.

For the ocean and energy sectors, the strategy for the next decade is clear. Scale the technologies that are winning today, aggressively unblock the infrastructure bottlenecks of tomorrow, and plan for a future that will, once again, look wholly different.

The post For proof of the energy transition’s resilience, look at what it’s up against appeared first on Climate Home News.

For proof of the energy transition’s resilience, look at what it’s up against

Climate Change

Post-COP 30 Modeling Shows World Is Far Off Track for Climate Goals

A new MIT Global Change Outlook finds current climate policies and economic indicators put the world on track for dangerous warming.

After yet another international climate summit ended last fall without binding commitments to phase out fossil fuels, a leading global climate model is offering a stark forecast for the decades ahead.

Post-COP 30 Modeling Shows World Is Far Off Track for Climate Goals

Climate Change

IMO head: Shipping decarbonisation “has started” despite green deal delay

The head of the United Nations body governing the global shipping industry has said that greenhouse gases from the global shipping industry will fall, whether or not the sector’s “Net Zero Framework” to cut emissions is adopted in October.

Arsenio Dominguez, secretary-general of the International Maritime Organization, told a new year’s press conference in London on Friday that, even if governments don’t sign up to the framework later this year as planned, the clean-up of the industry responsible for 3% of global emissions will continue.

“I reiterate my call to industry that the decarbonisation has started. There’s lots of research and development that is ongoing. There’s new plans on alternative fuels like methanol and ammonia that continue to evolve,” he told journalists.

He said he has not heard any government dispute a set of decarbonisation goals agreed in 2023. These include targets to reduce emissions 20-30% on 2008 levels by 2030 and then to reach net zero emissions “by or around, i.e. close to 2050”.

Dominguez said the 2030 emissions reduction target could be reached, although a goal for shipping to use at least 5% clean fuels by 2030 would be difficult to meet because their cost will remain high until at least the 2030s. The goals agreed in 2023 also included cutting emissions by 70-80% by 2040.

In October 2025, a decision on a proposed framework of practical measures to achieve the goals, which aims to incentivise shipowners to go green by taxing polluting ships and subsidising cleaner ones, was postponed by a year after a narrow vote by governments.

Ahead of that vote, the US threatened governments and their officials with sanctions, tariffs and visa restrictions – and President Donald Trump called the framework a “Green New Scam Tax on Shipping”.

Dominguez said at Friday’s press conference that he had not received any official complaints about the US’s behaviour at last October’s meeting but – without naming names – he called on nations to be “more respectful” at the IMO. He added that he did not think the US would leave the IMO, saying Washington had engaged constructively on the organisation’s budget and plans.

EU urged to clarify ETS position

The European Union – along with Brazil and Pacific island nations – pushed hard for the framework to be adopted in October. Some developing countries were concerned that the EU would retain its charges for polluting ships under its emissions trading scheme (ETS), even if the Net Zero Framework was passed, leading to ships travelling to and from the EU being charged twice.

This was an uncertainty that the US and Saudi Arabia exploited at the meeting to try and win over wavering developing countries. Most African, Asian and Caribbean nations voted for a delay.

On Friday, Dominguez called on the EU “to clarify their position on the review of the ETS, in order that as we move forward, we actually don’t have two systems that are going to be basically looking for the same the same goal, the same objective.”

He said he would continue to speak to EU member states, “to maintain the conversations in here, rather than move forward into fragmentation, because that will have a very detrimental effect in shipping”. “That would really create difficulties for operators, that would increase the cost, and everybody’s going to suffer from it,” he added.

The IMO’s marine environment protection committee, in which governments discuss climate strategy, will meet in April although the Net Zero Framework is not scheduled to be officially discussed until October.

The post IMO head: Shipping decarbonisation “has started” despite green deal delay appeared first on Climate Home News.

IMO head: Shipping decarbonisation “has started” despite green deal delay

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits