Amid a rapidly fracturing geopolitical order, there have been growing calls for China to “step into [the] leadership gap” left by the US on climate change.

While China has resisted such suggestions – at least officially – it has spent much of the past 12 months nurturing its international status as a partner for other countries, in areas ranging from the economy and global governance through to climate change.

President Xi Jinping has maintained a schedule packed with foreign-policy engagements, meeting with world leaders from Russia and India through to the EU.

Moreover, this April he made his first international climate speech since 2021, while attending a meeting on climate and the just transition hosted by Brazil.

As well as underscoring his nation’s ongoing commitment to climate action, Xi’s presence also hinted at the growing coordination between China and Brazil in this area.

More broadly, there is growing recognition of greater alignment between non-western countries – particularly in the global south – in the face of more aggressive US foreign policy.

Analysts note that pressure from the US could push groups such as the BRICS – of which Brazil and China are two founding members, alongside Russia and India – to become more cohesive and develop more concrete cooperation channels.

In a recent interview with Carbon Brief, UK climate envoy Rachel Kyte said that the “world is changing”, becoming “flatter” and that the BRICS – which now includes 11 countries, including South Africa, Egypt and Indonesia – are “more and more important”.

This Q&A explores the membership, climate stance and energy sectors of the BRICS nations, as well as the potential for China and the bloc to lead on climate change.

- What is the BRICS group?

- How do the BRICS approach climate change?

- Are Brazil and China in the BRICS ‘driving seat’?

- What is the role of fossil fuels in the BRICS?

- What is the economic impact of clean-tech?

- Will China and the BRICS emerge as climate leaders?

What is the BRICS group?

The BRICS group represents a number of emerging economies that aim to “strengthen” cooperation amongst themselves and to “increas[e] the influence of global south countries in international governance”.

They coordinate on a range of topics, from international finance to climate diplomacy.

It was founded by Brazil, Russia, India and China – hence, the original name “BRIC” – which later became “BRICS” with the inclusion of South Africa. More recently, it expanded again to include Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, Indonesia and Iran.

Saudi Arabia has been formally invited to join the bloc, but has not yet accepted the invitation. A number of others participate in the grouping as partner countries, including Malaysia, Thailand and Nigeria.

Together, the full members of the group represent 27% of global gross domestic product (GDP), 49% of the world’s population and 52% of emissions, according to Carbon Brief calculations illustrated below.

Four of the members – Brazil, China, India and South Africa – also form the BASIC bloc, a group with a significant voice at UN climate summits and other negotiations.

BASIC was formed in Beijing in 2009, with representatives from the four countries meeting to coordinate on climate negotiations from the standpoint of major emerging economies.

This culminated at the COP15 climate talks in Copenhagen in 2009, when the BASIC group issued a joint set of “non-negotiable terms” and went on to work directly with the US to agree the Copenhagen Accord.

The bloc has used less combative tactics in subsequent COPs, but it continues to issue joint statements on climate change and to strongly advocate for certain issues.

At both COP28 and COP29, BASIC submitted a proposal to have “unilateral trade measures related to climate change” – referring to policies such as the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) – added to the meeting agenda.

The request was denied both times.

How do the BRICS approach climate change?

Alongside BASIC, the BRICS group is also becoming increasingly focused on climate policy.

COP30 executive director Ana Toni, speaking at a September 2025 event at Tsinghua University attended online by Carbon Brief, said that BRICS countries have “realised that climate is not just a financial issue or a niche”, but rather a “pillar for prosperity, development and growth”.

Lucas Carlos Lima, professor of international law at the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Brazil, wrote in an April 2025 article for Modern Diplomacy that recent joint statements show the BRICS had “placed climate change squarely at the centre of the bloc’s agenda”.

The group has also been playing an increasingly significant role in other multilateral fora. For example, a BRICS proposal at the COP16 UN biodiversity negotiations in February formed the basis of an agreement to mobilise at least $200bn per year to protect nature.

Susana Muhamad, president of the COP16 nature talks, told Reuters in March that BRICS nations had been “bridge builders” in the negotiations.

She added:

“I understand there’s a lot of countries wanting to join BRICS, because…if you have to confront something like the US, you are not alone.”

Environment ministers of BRICS countries also recently issued a joint statement that “reaffirm[ed] our steadfast commitments” to addressing climate change, adding that BRICS “can positively contribute to…the global environmental agenda.”

Their finance ministers also agreed in May on a climate-finance framework, outlining priorities including “the reform of multilateral development banks, the scaling up of concessional finance and the mobilising of private capital to support climate efforts in the global south”.

The framework represents “common and collective BRICS action in the area of climate finance” for the first time, notes Tatiana Rosito, international affairs secretary at Brazil’s finance ministry.

The framework was adopted at the BRICS summit in July, where a number of leaders gathered to sign a joint declaration demanding that “accessible, timely and affordable climate finance” is provided to developing countries.

This, it adds, “is a responsibility of developed countries” under the Paris Agreement.

The statement also highlighted the nations’ “resolve to remain united in the pursuit of the purpose and goals of the Paris Agreement”, featuring 21 paragraphs in a section on climate change spanning just transitions, carbon markets and critical minerals.

“It is encouraging that BRICS nations called for more climate lending, deeper green bond markets and better carbon accounting,” Mirela Sandrini, interim executive director for Brazil at the World Resources Institute, said in a statement. She added:

“South-south collaboration of this scale and ambition can inject much-needed momentum into international climate diplomacy ahead of COP30.”

However, the BRICS leaders’ declaration also “acknowledge[s] fossil fuels will still play an important role in the world’s energy mix, particularly for emerging markets and developing economies”.

The inclusion of this language “undermin[es] the positives” of the bloc’s other statements on climate action, according to a response from Jacobo Ocharan, head of political strategies at Climate Action Network International.

Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, global climate and energy lead at WWF, agrees, saying climate change is “treated as background noise” in the joint statement, with “no clear articulation of the BRICS+ role in the global climate response”.

Are Brazil and China in the BRICS ‘driving seat’?

Much of the recent BRICS focus on climate change is due to Brazil being “in the driver’s seat”, says Kate Logan, director of the China climate hub and climate diplomacy at the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI), speaking to Carbon Brief.

As well as hosting COP30, Brazil recently chaired the G20 and is currently presiding over the BRICS. It used both of these forums to prioritise climate action on the agenda, she adds.

There has been frequent coordination between COP30, Brazilian and Chinese officials in the run-up to the conference.

This included a meeting of BRICS environment ministers held in April 2025, a separate April meeting between COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago and Chinese minister for the environment and ecology Huang Runqiu, as well as an earlier meeting in March between Huang and UN climate chief Simon Stiell.

Most significantly, Chinese president Xi Jinping appeared at a closed-door April 2025 meeting of global leaders organised by the UN and Brazil, telling his audience that “China’s actions to address climate change will not slow down”.

Many analysts saw the statement as a clear signal of China’s support for multilateralism, in sharp contrast to the US withdrawing from climate negotiations.

Xi’s participation in the meeting also underscored growing solidarity between China and Brazil on accelerating climate action.

Brazil and China have a long history of cooperation on environmental issues, including through the China-Brazil High-Level Coordination and Cooperation Commission (COSBAN).

The Brazilian government describes COSBAN as the “highest-level governmental mechanism” between the two countries. It includes tracks specifically focused on energy, agriculture and mining, as well as the environment and climate change.

But there has been a notable uptick in engagement under the new Lula administration.

For the current Brazilian administration, China is an “essential partner in global climate solutions”, according to a briefing note published by the Brazilian climate network Observatório do Clima.

A related opinion article in Brazilian newspaper Folha de S. Paolo, written by Stela Herschmann, climate policy specialist at the Observatório do Clima, and Beibei Yin, founder of environmental consultancy Bambu Consulting, argues that China and Brazil could form the “new G2” – the moniker given to the US-China alignment that they say shaped global climate policy for “more than two decades”.

They add that Brazil, through its unique role in the world and current position, can help “fill the current vacuum” of climate leadership. They write:

“Brazil enjoys the respect of the international community because it often mediates the divisions between developed and developing countries in climate negotiations…The presidency of COP30 and BRICS adds to this, making the country a natural candidate to fill the current vacuum of climate leadership.”

However, the two countries’ climate approaches have diverged at times.

Jennifer Allan, senior lecturer in international relations at Cardiff University, tells Carbon Brief: “These countries have several similar views, but also have diverged in the past.”

For example, she says, Brazil’s suggestion at COP26 of a “concentric” approach to cutting emissions, with emerging economies offering more stringent targets than other developing countries, was opposed by China, which wanted to “maintain the firewall” between developed and developing countries.

What is the role of fossil fuels in the BRICS?

Many BRICS nations remain heavily reliant on fossil fuels, both for electricity generation and to support their wider energy systems.

However, this picture is starting to shift, with almost all BRICS members having adopted net-zero targets ranging from 2050 for Brazil, South Africa and others, through to 2060 for China and Russia, or 2070 for India.

More tangibly, the addition of new clean-power projects means that fossil-fueled electricity generating capacity now makes up less than half of the installed total in the BRICS group as a whole in 2024, as shown in the figure below.

Non-fossil power, driven by “unprecedented” renewable energy growth in China, India and Brazil, accounted for 53% of the installed electricity generating capacity in BRICS countries overall in 2024, according to recent analysis by the thinktank Global Energy Monitor (GEM). This puts them in line with the global average.

Ethiopia, Brazil and China boast higher-than-average shares of clean capacity – at 100%, 88% and 57% respectively. India’s clean-capacity share stands at 43%.

Continued BRICS focus on clean energy makes it “unlikely that fossil capacity will overtake non-fossil again”, James Norman, research analyst at GEM, tells Carbon Brief, adding that much of this is driven by significant renewable additions in some members, particularly China.

While some BRICS members are continuing to commission “significant amounts of new coal-fired capacity”, he says, it remains uncertain whether these new plants will be completed, or if they will go on to operate at full capacity.

Several BRICS members are also leading producers and exporters of fossil fuels. Russia is a major exporter of all types of fossil fuels, the Statistical Review of World Energy shows, while the UAE, Iran and Indonesia have large oil- or coal-exporting industries.

The data shows that China and India, meanwhile, are by some distance the world’s largest and second-largest coal users, respectively, predominantly fueled by domestic mining. China alone accounts for more than half of global coal production and use.

Norman acknowledges that “fossil dominance remains largely unchanged” among some BRICS members.

He states that countries such as Iran, with “entrenched modes of power production”, or with “limited strategic interest in overhauling the energy sector, such as Russia”, are on a different trajectory to countries such as Brazil or China.

Nevertheless, he says, the “strong economic case for solar and wind”, as well as the fact that nearly all BRICS countries have announced renewable energy targets, “makes continued growth in clean energy across the group highly likely”.

In the short term, meanwhile, the continued reliance of some members on fossil fuels might not lessen the BRICS group’s climate ambition overall. It is “notable” that Russia does not seem to be “blocking” the “solid outcomes” of recent BRICS climate negotiations, Logan tells Carbon Brief.

Indeed, the 2024 Kazan declaration, which featured a lengthy and detailed section on climate change, was released under the Russian BRICS presidency.

Still, the group is not a united front in all areas, for example the rivalry between China and India. Tensions remain high between the two countries on a number of issues, from border disputes to supply chains and geopolitical alliances.

This has spilled into climate-related topics, with India complaining about China’s construction of mega-dams in the Himalayas and launching anti-dumping investigations into solar imports from China.

At COP29, China and India at times took up conflicting stances during negotiations – most notably during the final stages of the climate finance deal, where China “helped prevent” efforts by India to block the deal, Logan wrote in an analysis for Dialogue Earth.

Another area of contention for India at COP29 was CBAM, which it said contributed to a “very, very competitive, hostile environment” that made it “difficult” to enable an energy transition.

By contrast, Logan tells Carbon Brief, China is “much less worried” about CBAM.

(Brazil, too, is unlikely to push hard to include CBAM and other “unilateral” trade measures in the COP30 agenda, Allan says, in order to maintain its “neutral” position as the holder of the COP presidency and the trust of other parties. Indeed, it is reportedly pushing for this issue to be taken up in a new forum, completely outside the climate talks.)

Nevertheless, India and China are united in climate negotiations by their commitment to ensuring all agreements uphold the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities (CBDR-RC).

“This is something [in which] they’ll continue to be aligned”, Logan says, “but how it plays out in practice is where you start to see divergences”.

A recent rapprochement in China-India relations saw Indian prime minister Narendra Modi visit China for the first time in seven years.

The two countries also came together at the International Maritime Organization, where they successfully pushed for publicly-available data on shipping emissions to be anonymised.

Earlier, Brazil, China, South Africa and several other developing countries also lobbied against the creation of a global levy on shipping emissions.

Allen notes that whether or not BRICS and BASIC can align on climate may, ultimately, be a moot point, given that BASIC is just one of several coalitions that China operates in and that it is currently “less active” than other coalitions.

For example, she says, unlike the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDC) group, BASIC “doesn’t negotiate as a group in contact groups” at the UN climate talks. She adds:

“Multiple coalitions are a way for [a country] to multipl[y] their influence, while also perhaps hiding its individual views among those of the group.”

What is the economic impact of clean-tech?

Beyond the realms of climate diplomacy, it is increasingly clear that there is a hard-nosed economic reality to the positions being taken by China and other BRICS nations.

Indeed, as China works with Brazil and the BRICS to centre emerging markets’ concerns in climate policy, it also plays a key role in the economics of the energy transition.

The country accounts for more than 80% of global solar manufacturing, more than 70% of electric vehicle production and more than 75% of battery production.

While most of this is consumed domestically, exports of each of these categories – which it often calls the “new-three” – are “booming”, finance news outlet Caixin reports.

Historically these exports would have been destined for developed countries. But, in 2024, “half of all China’s exports of solar and wind power equipment and electric vehicles (EVs) [went] to the global south”, Lauri Myllyvirta and Hubert Thieriot, lead analyst and data lead at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), write at Dialogue Earth.

Separate analysis by Myllyvirta for Carbon Brief revealed that China’s exports of clean-energy technologies in 2024 alone will reduce emissions in the rest of the world by 1%, avoiding some 4bn tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2 over their lifetimes).

Moreover, clean-energy industries accounted for more than 10% of China’s GDP in 2024 for the first time ever, driving a quarter of economic growth that year.

Meanwhile, Chinese lending overseas is also increasingly focused on low-carbon infrastructure, according to the Boston University Global Development Policy Center.

Their analysis finds that the “share of renewable energy in China’s portfolio has increased significantly”, with solar and wind projects “dominat[ing]” the types of projects funded in 2022 and 2023.

This stands in sharp contrast to typical Chinese lending activity before 2021, which showed a preference for conventional power projects, such as coal and hydropower.

According to Myllyvirta and Thieriot, the “important role that clean-energy technology plays in the country’s economy and exports” will encourage China to ensure that the global energy transition “keeps accelerating”.

They add: “That will be seen in bilateral lending and diplomacy, and could also lead the country to take more forward-leaning positions in multilateral climate negotiations.”

Will China and the BRICS emerge as climate leaders?

With the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement under the Trump administration, there have been increasing calls for China to take up the mantle of climate leadership.

Many are watching for signs of whether China’s upcoming international climate pledge, which may be published by the UN general assembly meeting next week, will contain ambitious targets that will encourage greater global ambition.

Beatriz Mattos, research coordinator at Brazil-based climate-research institute Plataforma CIPÓ, tells Carbon Brief that China’s position as a “major investor in the renewable energy sector” means there is “enormous potential” for both it and the BRICS to assume a climate leadership role.

China, at least publicly, is eschewing these calls. In an interview with state-owned magazine China Newsweek, climate envoy Liu Zhenmin said in response to a question about China’s climate leadership that the calls are just “the west giving us a ‘tall hat’” – an expression meaning trying to flatter China. He added:

“Of course, within their respective camps, major countries should play a more leading role, such as the EU and US in the developed countries camp, and the BASIC countries in the developing countries camp. But BASIC cannot be a substitute for all developing countries, and developing countries will still participate in [climate] negotiations within the framework of ‘G77+China’. This is the basis for cooperation in the global south.”

Notably, this does not seem to preclude China from agreeing to “demonstrate leadership” in tandem with others, as seen in an EU-China joint statement on climate change published in late July.

BASIC is “important for China in climate negotiations given the influence of other large emerging economies”, Yixian Sun, associate professor in international development at the University of Bath, tells Carbon Brief.

“On many issues (especially sensitive issues regarding its developing country status), China doesn’t want to stand out by itself,” he says, with the grouping providing cover in negotiations.

Mattos agrees, stating that “remaining part of this group serves as a way [for China] to reinforce its identity as a developing country in climate negotiations”.

More broadly, it will likely continue to align with the other BRICS nations, when this offers a way to advance its positions in climate negotiations.

Sun expects Brazil and China to sustain their elevated levels of climate cooperation even after Brazil hands over the COP presidency, based on their 2023 joint statement. However, he says there are still questions around what new bilateral climate initiatives would look like and how “concrete” they would be in practice.

Looking ahead, Logan notes, BRICS could also be in a position to sustain its influence if India hosts COP33 in 2028.

“BRICS has in multiple documents endorsed India’s bid for COP33”, she says, which, given India’s presidency of BRICS in 2026, could allow Brazil and China to “influence India in a more constructive direction” on climate, over a number of years.

The post Q&A: Will China and the BRICS fill the ‘leadership gap’ on climate change? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: Will China and the BRICS fill the ‘leadership gap’ on climate change?

Greenhouse Gases

UNEP: New country climate plans ‘barely move needle’ on expected warming

The latest round of country climate plans ‘barely move the needle’ on future warming, the head of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) has warned.

Executive director Inger Anderson made the comments as UNEP published its 16th annual assessment of the global “emissions gap”.

The report sets out the gap between where global emissions are headed – based on announced national policies and pledges – and what is needed to meet international temperature targets.

It finds that the latest round of national climate plans – which were due to the UN this year under Paris Agreement rules – will have a “limited effect” on narrowing this emissions gap.

Currently, the world is on track for 2.3-2.5C of warming this century if all national emissions-cutting plans out to 2035 are implemented in full, according to the report.

In a statement, UNEP executive director Inger Anderson said: “While national climate plans have delivered some progress, it is nowhere near fast enough.”

A decade on from the Paris Agreement, the UN agency credits the climate treaty for its “pivotal” role in lowering global temperature projections and driving a rise of renewable energy technologies, policies and targets.

Nevertheless, it warns that countries’ failure to cut emissions quickly enough means the world is “very likely” to breach the Paris Agreement’s aspirational 1.5C temperature limit “this decade”.

It urges countries to make any “overshoot” of the 1.5C warming target “temporary and minimal”, so as to reduce damages to people and ecosystems, as well as future reliance on “risky and costly” carbon removal methods.

Among the other key findings of the report are that China’s emissions could peak in 2025, while the impact of recent climate policy reversals in the US are likely to be outweighed by lower emissions in other countries in the coming years.

(See Carbon Brief’s detailed coverage of previous reports in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024.)

Greenhouse gas emissions continue to grow

The UNEP report finds that global emissions of greenhouse gases – carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, nitrous oxide and fluorinated gases (F-gases) – reached a record 57.7bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) in 2024. This marks a 2.3% increase compared to 2023 emissions.

This increase is “high” compared to the rise of 1.6% recorded between 2022 and 2023, the report says.

This rate of increase is more than four times higher than the average annual emissions growth rate throughout the 2010s, the report notes, and is comparable with the 2.2%-per-year rate seen in the 2000s.

The chart below shows total greenhouse gas emissions between 1990 and 2024.

It illustrates that “fossil CO2” (black), driven by the combustion of coal, oil and gas, is the largest contributor to annual emissions and the main driver of the increase in recent decades, accounting for around 69% of current emissions.

Methane (grey) plays the second largest role. Meanwhile, emissions from nitrous oxide (blue) fluoride gases (orange) and land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF, in green) make up 24% of total greenhouse gas emissions.

The report notes that all “all major sectors and categories” of greenhouse gas emissions saw an increase in 2024. For example, fossil CO2 emissions increased by 1.1% between 2023 and 2024.

However, it highlights that deforestation and land-use emissions played a “decisive” role in the overall increase last year. According to the report, net LULUCF CO2 emissions rose by a fifth – some 21% – between 2023 and 2024.

This spike is in contrast to the past decade, the report notes, where emissions from land-use change have “trended downwards”.

It says one of the reasons for the increase in LULUCF emissions over 2023-24 is the rise in emissions from tropical deforestation and degradation in South America, which were among the highest recorded since 1997.

The authors also break down changes in greenhouse gases by country or country group. They note that the six largest emitters in the world are China, the US, India, the EU, Russia and Indonesia.

The report finds that, when emissions from land use are excluded, emissions from the G20 countries accounted for 77% of the overall increase in emissions over 2023-24. Meanwhile, the “least developed countries” group contributed only 3% of the increase.

The graph below shows contributions to the change in greenhouse gas emissions between 2023 and 2024 for the five highest-emitting countries and groups, as well as for the rest of the G20 countries (purple), the rest of the world (grey), LULUCF globally (green) and international transport (dark blue).

The bottom horizontal black line shows the 56.2GtCO2e emitted in 2023. The size of each bar indicates the change in emissions between 2023 and 2024. The top horizontal black line shows the 57.7GtCO2e emitted in 2024.

The chart illustrates how India and China are the countries that recorded the largest individual increase in emissions between 2023 and 2024, while the EU is the only grouping where emissions decreased.

India and China recorded the largest absolute increase in emissions beyond the land sector. However, Indonesia saw the highest percentage increase of 4.6% (compared to 3.6% for India and 0.5% for China). In contrast, emissions from the EU decreased by 2.1%.

New national climate plans fall short

Under the terms of the Paris Agreement, countries are required to submit national climate plans, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs), to the UN every five years. These documents describe each country’s plans to cut emissions and adapt to climate change.

The deadline for countries to submit NDCs for 2035 was February 2025.

(Carbon Brief reported earlier this year that 95% of countries had missed the February deadline and, more recently, that just one-third of new plans submitted by the end of September expressed support for “transitioning away” from fossil fuels.)

By September 2025, 64 parties had submitted or announced their new NDCs. UNEP says that 60 of these countries accounted for 63% of global emissions. Meanwhile, only 13 countries, accounting for less than 1% of global emissions, had updated their emissions reduction targets for 2030.

Writing in the foreword to the report, UNEP’s Inger Andersen says that “many hoped [the pledges] would demonstrate a step change in ambition and action to lower greenhouse gas emissions and avoid an intensification of the climate crisis that is hammering people and economies”. However, she adds that “this ambition and action did not materialise”.

The report emphasises that “immediate and stringent emissions reductions” are the “fundamental ingredient” for meeting the Paris temperature goal of keeping warming this century to well-below 2C and making efforts to keep it to 1.5C.

However, it adds that the new NDCs and “current geopolitical situation” do not provide “promising signs” that these emissions cuts will happen.

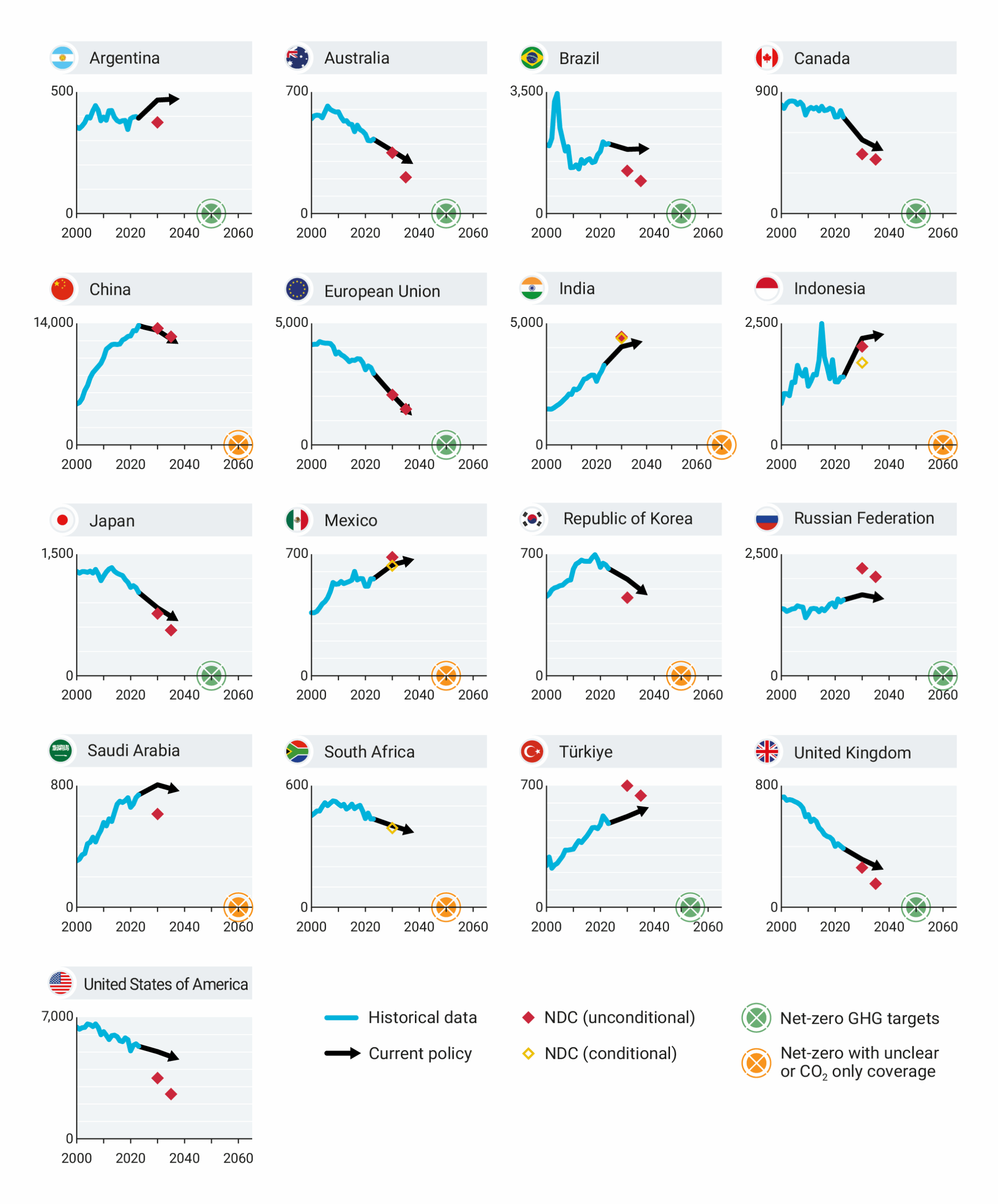

The report presents a “deep dive” into the emissions reduction targets of G20 countries – the world’s largest economies, which are collectively responsible for more than three-quarters of global emissions.

The analysis investigates NDCs and policy updates as of November 2024.

None of the G20 countries have strengthened their targets for 2030, according to the report. However, it finds that seven G20 countries have submitted NDCs with emissions reduction targets for 2035. The EU, China and Turkey have announced targets, but had not yet submitted 2035 climate plans to the UN by the time the report was finalised.

According to the report, the new NDCs and policy updates of G20 countries lead to a reduction in projected emissions by 2035. However, these reductions are “relatively small and surrounded by significant uncertainty”, it cautions.

Nevertheless, UNEP says there are a number of G20 countries whose emissions projections have seen “significant changes” in this year’s report, including the US and China.

For the first time, the projections in the gap report suggest that China will see its emissions peak in 2025, followed by a reduction in emissions of 0.3-1.4GtCO2e by 2030. According to the report, this is due to the growth of renewable electricity generation in the country “outpacing” overall power demand growth.

In contrast, the authors warn that projections for US emissions in 2030 have increased by 1GtCO2e compared to last year’s assessment, mainly due to “policy reversals”.

(Since taking office in January 2025, Donald Trump has triggered the process of withdrawing the US from the Paris Agreement for the second time and dismantled US climate policies implemented under Joe Biden. The UNEP report does not specifically mention Trump or his administration.)

However, it finds that lower greenhouse gas projections for China and several other countries outweigh the higher projections in the US by 2030.

Overall, the report projects that, under current climate policies, annual emissions from G20 countries will drop to 35GtCO2 by 2030 and 33Gt by 2035.

China is the largest contributor to this projected reduction, followed by the EU then the US, according to the report. (Emissions from the US are still projected to decline, albeit much more slowly than previously expected.)

It adds that other G20 members are on “clear downward emission trends”, noting that “several more” might see emissions “peak or plateau between 2030 and 2035” under current policies.

The graph below shows the historical emissions (light blue) and projected emissions (dark blue) of the G20 members, along with their NDCs for 2030 and 2035 (shown by the diamonds) and net-zero targets (circles).

The graph shows that some countries, such as Turkey and Russia, are projected to cut emissions more rapidly than they have pledged under their NDCs. In contrast, other nations, such as the UK and Canada, are anticipated to fall short of the emissions-reduction goals set out in their national climate plans.

New NDCs and policy updates lower expected emissions in 2035

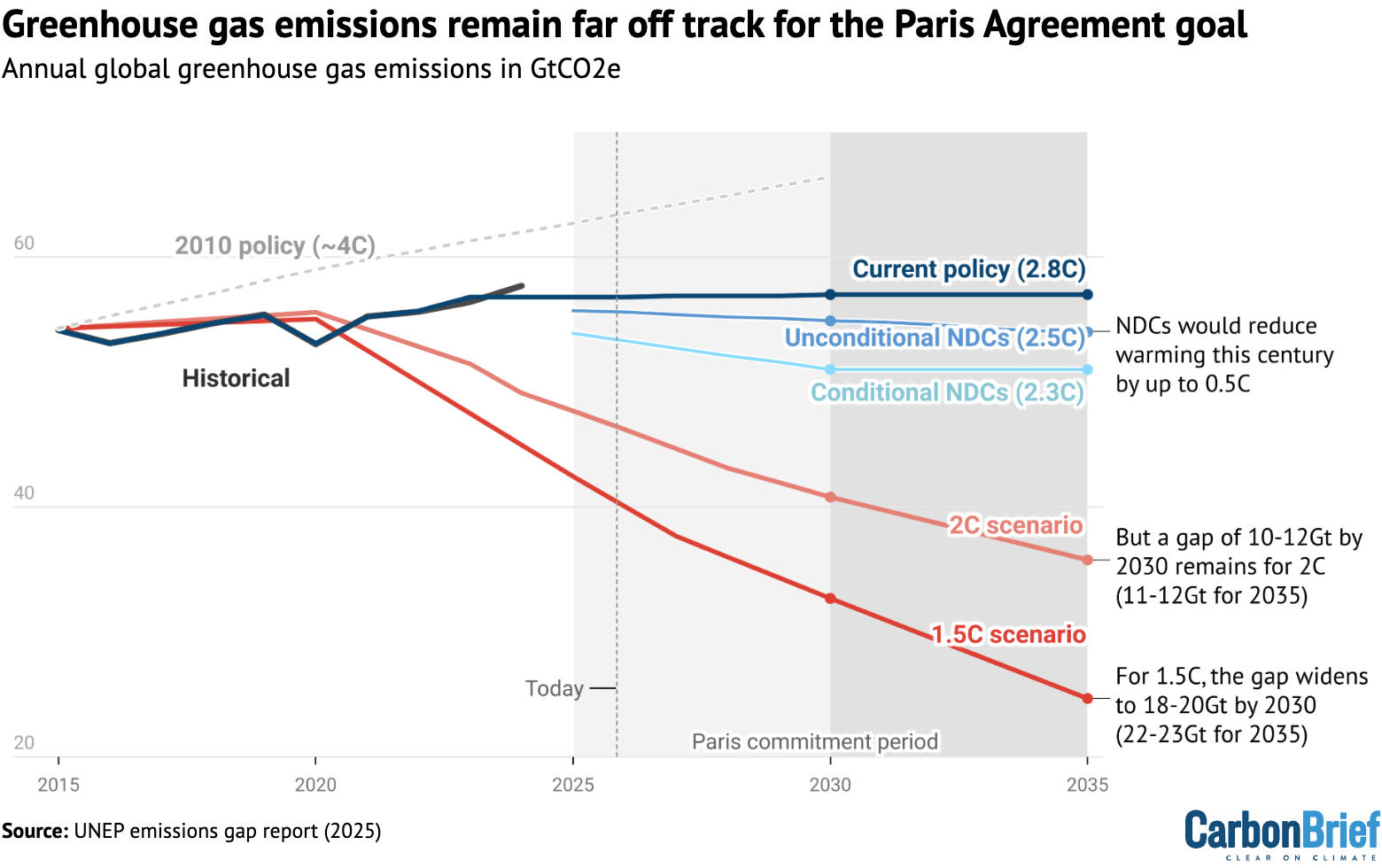

The report conducts an “emissions gap” analysis that compares the emissions that would be released if countries follow their climate policies or pledges, with the levels that would be needed in order to hold warming below 2C, 1.8C and 1.5C with limited or no overshoot.

The “gap” between these two values shows how much further emissions would need to be reduced in order to limit warming below global temperature thresholds.

To explore potential rises in global temperature over the coming years and decades, the report authors use a simple climate model, or “emulator”, called FaIR. They assess a range of potential futures:

- A “current policy” scenario, which assumes that countries follow policies adopted as of November 2024. This scenario also assumes the full implementation of announced policy rollbacks in the US as of September 2025.

- An “unconditional NDCs” scenario, which assumes the implementation of NDCs that do not depend on external support. This scenario includes the US NDC, as withdrawal from the Paris Agreement will not be complete until January 2026.

- A “conditional NDCs” scenario that further assumes the implementation of NDCs that depend on external support, such as climate finance from wealthier countries.

The report also analyses two “scenario extensions”, which explore the post-2035 implications of current policies, NDCs and net-zero pledges:

- A “current policies continuing” scenario, which “follows current policies to 2035 and assumes a continuation of similar efforts thereafter”.

- A “conditional NDCs plus all net-zero pledges” scenario, which is “the most optimistic scenario included”. This scenario assumes the “conditional NDC” scenario is achieved until 2035 and then all net-zero or other long-term low emissions developments strategies are followed thereafter, excluding that of the US.

The authors note that emissions projections for 2030 under the “current policy” scenario in this year’s report are slightly larger than they were in last year’s assessment. The authors say this is “mainly” due to policy rollbacks in the US.

In contrast, this report projects slightly lower emissions for 2035 than last year’s report, as policy changes in the US are offset by “improved 2035 policy estimates” in other countries.

The authors find that the new NDCs have “no effect” on the 2030 gap when compared to last year’s assessment.

According to the report, implementing unconditional NDCs would result in emissions in 2030 being 12GtCO2e above the level required to limit warming to 2C. This number rises to 20GtCO2e for a 1.5C scenario.

Also implementing conditional NDCs would shrink these gaps by around 2GtCO2e, the report says.

(The authors note that these numbers are slightly smaller than in last year’s report, but say this is not a reflection of “strengthening of 2030 NDC targets”, but instead from “updated emission trends by modelling groups and methodological updates”.)

The report adds that the formal withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement for a second time will mean that emissions laid out in the US NDC are not counted. This will increase the emissions gap by 2GtCO2e, the report says.

According to the report, the new NDCs do narrow the 2035 emissions gap compared to last year’s assessment. The report says:

“The unconditional and conditional NDC gaps with respect to 2C and 1.5C pathways are 6bn and 4bn tonnes of CO2e lower than last year, respectively.”

This means that the “emissions gap” between a world that follows conditional NDCs and one that limits warming to 2C above pre-industrial temperatures is 6GtCO2e smaller in this year’s report than last year’s. Similarly, the gap between the “conditional NDCs” scenario and the 1.5C scenario is now 4GtCO2e smaller.

Despite the improvement, the report warns that the emissions gap “remains large”.

The graph below shows historical and projected global emissions over 2015-35 under the current policy (dark blue), unconditional NDCs (mid blue), conditional NDCs (light blue), 2C (pink) and 1.5C (red) scenarios.

The report also warns that there is an “implementation gap”, as countries are currently not on track to achieve their NDC targets.

The authors say the implementation gap is currently 5GtCO2e for unconditional NDCs by 2030 and 7GtCO2e for conditional NDCs, or around 2GtCO2e lower once the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement is complete next year.

‘Limited’ progress on reducing future warming

UNEP calculates that the full implementation of both conditional and unconditional NDCs would reduce emissions in 2035 by 12% and 15%, respectively, on 2019 levels. However, these percentages shrink to 9% and 11% if the US NDC is discounted.

The projections suggest there will be a “peak and decline” in global emissions. However, the report says the large range of estimates that remain around global emissions reductions means there is “continued uncertainty” around when peaking could happen.

Projected emissions cuts by 2035 are “far smaller” than the 35% reduction required to align with a 2C pathway and the even steeper cut of 55% required for a 1.5C pathway, the report says.

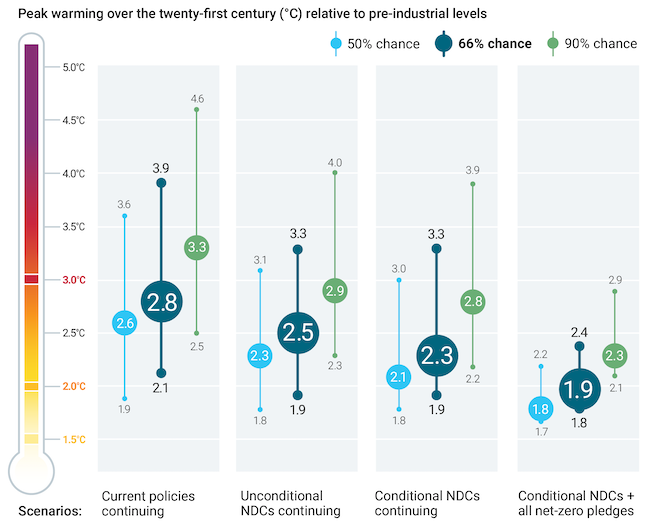

The authors say that temperature projections set out in this year’s report are only “slightly lower” – at 0.3C – than last year’s assessment.

It notes that new policy projections and NDC targets announced since the last assessment have lowered warming projections by 0.2C. “Methodological updates” are responsible for the remaining 0.1C.

Furthermore, the forthcoming withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement would reverse 0.1C of this “limited progress”, the report notes.

Responding to these figures in the report’s foreword, UNEP’s Anderson says the new pledges have “barely moved the needle” on temperature projections.

The chart below shows the different warming projections under four of the scenarios explored in the report.

It shows how, under the current policies pathway, there is a 66% chance of warming being limited to 2.8C. In a scenario where efforts are made to meet conditional NDCs in full, there is the same probability that warming could be capped at 2.3C.

In the most optimistic scenario – where all NDCs and net-zero targets are implemented – there is a 66% chance that warming could be constrained to 1.9C. (This projection remains unchanged since last year’s report.)

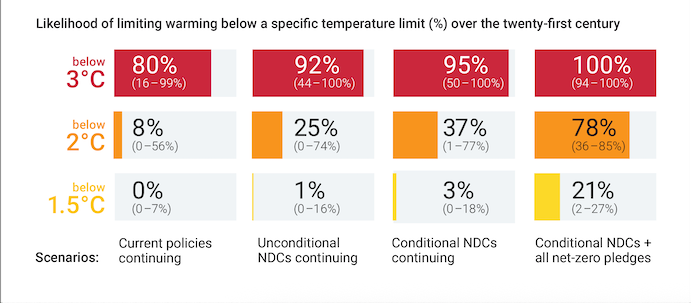

The report warns that, across all scenarios, the central warming projections would see global warming surpass 1.5C “by several tenths of a degree” by mid-century. And it calculates there is a 21-33% likelihood that warming could exceed 2C by 2050.

Nevertheless, it stresses that the Paris Agreement has been “pivotal” in reducing temperature projections. Policies at the time of the treaty’s adoption would have put the world on track for warming “just below 4C”.

1.5C limit could be exceeded within a decade

UNEP notes that its updated temperature projections underscore an “uncomfortable truth” that surpassing the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C warming limit is “increasingly near”.

The limit – which refers to long-term warming over a pre-industrial baseline and not average warming in any particular year – could be exceeded “within the next decade”, it says. However, the report emphasises that it remains “technically possible” to return to 1.5C by 2100.

Global inaction on emissions in the 2020s means that 1.5C pathways explored in previous emission gap reports and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s sixth assessment cycle are “no longer fully achievable”, according to UNEP.

Moreover, a lack of “stringent emissions cuts” in recent years means climate pathways with “limited” overshoot of 1.5C are also “slipping out of reach”, the authors say.

A future of “higher and potentially longer” overshoot of 1.5C is “increasingly likely”, they warn.

Climate “overshoot” pathways are those where temperatures exceed 1.5C temporarily, before being brought back below the threshold using techniques that remove carbon from the atmosphere.

(For more on climate overshoot, read Carbon Brief’s detailed write-up of a recent conference dedicated to the concept.)

Elsewhere, the report notes the remaining “carbon budget” for limiting warming to 1.5C without any overshoot of the goal will “likely be exhausted” before 2030.

(The carbon budget is the total amount of CO2 that scientists estimate can be emitted if warming is to be kept below a particular temperature threshold. Earlier this year, the Indicators of Global Climate Change report estimated the remaining carbon budget had declined by three-quarters between the start of 2020 and the start of 2025.)

The graphic below illustrates the percentage likelihood of limiting warming under 1.5C, 2C and 3C under the four scenarios set out in the report.

It shows how the chances of limiting warming to below 1.5C throughout the 21st century is close to zero in all but the most optimistic scenario. In the scenario where conditional NDCs and net-zero pledges are met, the chances of limiting temperatures below the goal is just 21%.

The report stresses that it is critical to limit “magnitude and duration” of overshoot to avoid “greater losses for people and ecosystems”, higher adaptation costs and a heavier reliance on “costly and uncertain carbon dioxide removal”.

Roughly 220GtCO2 of carbon removals will be required to reverse every 0.1C of overshoot, according to the report. This is equivalent to five years of global annual CO2 emissions.

The report also warns that it is “highly unlikely” that all risks and hazards will “reverse proportionately” after a period of temperature overshoot.

UNEP states that pursuing the 1.5C temperature goal is nevertheless a “legal, moral and political obligation” for governments regardless of whether warming exceeds the target.

The UN agency emphasises that the 2015 Paris Agreement establishes “no target date or expiration” for its temperature goal – and points to the International Court of Justice’s recent advisory opinion that 1.5C remains the “primary target” of the climate treaty.

The post UNEP: New country climate plans ‘barely move needle’ on expected warming appeared first on Carbon Brief.

UNEP: New country climate plans ‘barely move needle’ on expected warming

Greenhouse Gases

Q&A: COP30 could – finally – agree how to track the ‘global goal on adaptation’

Nearly a decade on from the Paris Agreement, there is still not an agreed way to measure progress towards its “global goal on adaptation” (GGA).

Yet climate impacts are increasingly being felt around the world, with the weather becoming more extreme and the risk to vulnerable populations growing.

At COP30, which takes place next month, negotiators are set to finalise a list of indicators that can be used to measure progress towards the GGA.

This is expected to be one of the most significant negotiated outcomes from the UN climate summit in Belém, Brazil.

In a series of open letters running up to the summit, COP30 president-designate André Corrêa do Lago wrote that adaptation was “no longer a choice” and that countries needed to seize a “window of opportunity”:

“There is a window of opportunity to define a robust framework to track collective progress on adaptation. This milestone will…lay the groundwork for the future of the adaptation agenda.”

However, progress on producing an agreed list of indicators has been difficult, with nearly 90 experts working over two years to narrow down a list of almost 10,000 potential indicators to a final set of just 100, which is supposed to be adopted at COP30.

Below, Carbon Brief explores what the GGA is, why progress on adaptation has been so challenging and what a successful outcome would look like in Belém.

What is the GGA?

The GGA was signed into being within the Paris Agreement in 2015, but the treaty included limited detail on exactly what the goal would look like, how it would be achieved and how progress would be tracked.

The need to adapt to climate change has long been established, with the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, adopted in 1992, noting that parties “shall…cooperate in preparing for adaptation to the impacts of climate change”.

In the subsequent years, the issue received limited focus, however. Then, in 2013, the African Group of Negotiators put forward a proposed GGA, setting out a target for adaptation.

This was then formally established under article 7.1 of the Paris text two years later. The text of the treaty says that the GGA is to “enhanc[e] adaptive capacity, strengthen…resilience and reduc[e] vulnerability to climate change”.

According to the World Resources Institute (WRI), the GGA was designed to set “specific, measurable targets and guidelines for global adaptation action, as well as enhancing adaptation finance and other types of support for developing countries”.

However, unlike the goal to cut emissions – established in article 4 of the Paris Agreement – measuring progress on adaptation is “inherently challenging”.

Emilie Beauchamp, lead for monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) for adaptation at the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), tells Carbon Brief that this challenge relates to the context-specific nature of what adaptation means. She says:

“The main [reason] it’s hard to measure progress on adaptation is because adaptation is very contextual, and so resilience and adapting mean different things to different people, and different things in different places. So it’s not always easy to quantify or qualify…You need to integrate really different dimensions and different lived experiences when you assess progress on adaptation. And that’s why it’s been hard.”

Beyond this, attribution of the impact of adaptive measures remains a “persistent challenge”, according to Dr Portia Adade Williams, a research scientist at the CSIR-Science and Technology Policy Research Institute and Carbon Brief contributing editor, “as observed changes in vulnerability or resilience may result from multiple climatic and non-climatic factors”. She adds:

“In many contexts, data limitations and inconsistent monitoring systems, particularly in developing countries, constrain systematic tracking of adaptation efforts. Existing monitoring frameworks tend to emphasise outputs, such as infrastructure built or trainings conducted, rather than outcomes that reflect actual reductions in vulnerability or enhanced resilience.”

Despite these challenges, the need for increased progress on adaptation is clear. Nearly half of the global population – around 3.6 billion people – are currently highly vulnerable to these impacts. This includes vulnerability to droughts, floods, heat stress and food insecurity.

However, for six years following the adoption of the Paris Agreement, the GGA did not feature on the agenda at COP summits and there was limited progress on the matter.

This changed in 2021, at COP26 in Glasgow, when parties initiated the two-year Glasgow-Sharm el-Sheikh work program to begin establishing tangible adaptation targets.

This work culminated at COP28 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, with the GGA “framework”.

Agreeing the details of this framework and developing indicators to measure adaptation progress has been the main focus of negotiations in recent years.

What progress has been made?

Following the establishment of the GGA, there was – for many years – only limited progress towards agreeing how to track countries’ adaptation efforts.

COP28 was seen as a “pivotal juncture” for the GGA, with the creation of the framework and a new two-year plan to develop indicators, which is supposed to culminate at COP30.

Negotiations across the two weeks in Dubai in 2023 were tense. It took five days for a draft negotiating text on the GGA framework to emerge, due to objections from the G77 and China group of developing countries around the inclusion of adaptation finance.

Within the GGA – as with many negotiating tracks under the UNFCCC – finance to support developing nations is a common sticking point. Other disagreements included the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” (CBDR–RC).

Ultimately, a text containing weakened language around both CBDR-RC and finance was waved through at the end of COP28 and a framework for the GGA was adopted.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Ana Mulio Alvarez, a researcher on adaptation at thinktank E3G, said that the framework was the “first real step to fulfilling” the adaptation mandate laid out in the Paris Agreement, adding:

“The GGA is the equivalent of the 1.5C commitment for mitigation – a north star to guide efforts. It will be hugely symbolic if the GGA indicators are agreed at COP and the GGA can be implemented.”

The framework agreed at COP28 includes 11 targets to guide progress against the GGA. Of these, four are related to what it describes as an “iterative adaptation cycle” – risk assessment, planning, implementation and learning – and seven to thematic targets.

These “themes” cover water, food, health, ecosystems, infrastructure, poverty eradication and cultural heritage.

Within these, there are subgoals for countries to work towards. For example, within the water theme, there is a subgoal of achieving universal access to clean water.

While this framework was broadly welcomed as a step forward for adaptation work, there remains concern from some experts about the focus of the programme.

Prof Lisa Schipper, a professor of development geography at the University of Bonn, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) author and Carbon Brief contributing editor, tells Carbon Brief that without the framework there would likely have been continued delays, but there was still “significant scientific pushback against this approach to adaptation”.

She notes that the IPCC’s sixth assessment report (AR6) “didn’t necessarily provide any concrete inputs that could be useful for the GGA”. Beyond this, there are political challenges that the framework does not address, Schipper adds, continuing:

“There are also political reasons why global-north countries or annex-one countries don’t necessarily want specificity [in adaptation targets], because they also don’t want to be held accountable and to be forced to pay for things, right? So, the science was pathetic in one way, it was just not sufficient. And then you have a political agenda that’s fighting against clarity on this.

“So, even though [the framework] came together, it was still not very concrete, right? It was a framework, but it didn’t have a lot in it.”

As with the language around finance, thematic targets within the GGA were weakened over the course of the negotiations. Additionally, parties ultimately did not agree to set up a specific, recurring agenda item to continue discussing the GGA.

However, a further two-year programme was established at COP28. The UAE-Belém work programme was designed to establish concrete “indicators” that can be used to measure progress on adaptation going forward.

Why is it hard to choose adaptation indicators?

In the two years following COP28, work has been ongoing to narrow down a potential list of more than 9,000 indicators under the GGA to just 100.

At the UNFCCC negotiations in June 2024 in Bonn, parties agreed to ask for a group of technical experts to be convened to help with this process.

This led to a group of 78 experts meeting in September 2024. They were split into eight working groups – one for each of the seven themes and one for the iterative adaptation cycle – to begin work reviewing a list of more than 5,000 indicators, which had already been compiled from submissions to the UNFCCC.

In October 2024, a second workshop was held under the UAE-Belém work programme, at which the experts agreed that they should also consider an additional 5,000 indicators compiled by the Adaptation Committee, another body within the UN climate regime.

One key challenge, Beauchamp tells Carbon Brief, was that the group of experts had very limited time and a lack of resources. She expands:

“They had to finish their work by the end of the summer [of 2025]. This means they’ve not even had a year [and] they have no funding. So of the 78 experts, the number of whom could actually contribute was much lower, and it’s not by lack of desire and expertise. But [because] they have day jobs, they have families…And the lack of clear instructions from parties also didn’t help.”

COP29 formed the mid-way point in the work programme to develop adaptation indicators, with parties stressing it was “critical” to come away with a decision from the summit.

As with previous sessions, finance quickly became a sticking point in negotiations, however, alongside the notion of “transformational adaptation”.

This is a complex concept centred around the idea of driving systemic shifts – in infrastructure, governance or society more broadly – so as to address the root causes of vulnerability to climate change.

Ultimately, COP29 adopted a decision that made reference to finance as “means of implementation” (MOI), recognised transformational adaptation and launched the Baku Adaptation Roadmap (BAR). The BAR is designed to advance progress towards the GGA, however, the details of how it will operate are still unclear.

Going into the Bonn climate negotiations in June 2025, the list of potential indicators had been “miraculously” refined to a list of 490 through further work by the group of experts. While this was a major step forward, it was still a long way off the aim of agreeing to a final set of just 100 indicators at COP30.

Once again, disagreement quickly arose in Bonn around finance and this dominated much of the two weeks of negotiations. As such, a final text did not get uploaded until mid-way through the final plenary meeting of the negotiations.

This was seen as contentious, as some parties complained that they did not have time to fully assess it, before it was gavelled through.

Bethan Laughlin, senior policy specialist at the Zoological Society of London, tells Carbon Brief:

“Adaptation finance has consistently lagged behind mitigation for decades, despite growing recognition of the urgent need to build resilience to climate shocks. The gap between the needs of countries and the funding provided is stark, with an adaptation financing gap in the hundreds of billions annually.

“Within the GGA negotiations, the implications of this finance issue are clear. Disagreements persist over how MoI [finance] should be measured in the indicator set, particularly around whether private finance should count, how support from developed countries is defined, and how national budgets are tracked versus international climate finance.”

The final text produced in Bonn was split into two, with an agreed section capturing the GGA indicators and a separate “informal note” covering the BAR and transformation adaptation.

Importantly, the main text invited the experts to continue working on the indicators and to submit a final technical report with a list of potential indicators by August 2025.

As this work continued, one of the biggest challenges was “balancing technical rigour with political feasibility while ensuring ambition”, says Laughlin, adding:

“The scale and diversity of adaptation action means a diverse menu of indicators per target is needed, but this must not be so vast as to be unfeasible for countries to measure, especially those countries with limited resources and capacity.”

Meetings took place subsequently, within which experts focused on “ensuring adaptation relevance of indicators, reducing redundancy and ensuring coverage across thematic indicators”, according to a technical report.

Beauchamp notes the importance of these themes for continued work on adaptation, saying:

“The themes were really helpful to bring some attention and to communicate about the GGA. They echo more easily what adaptation results can look like, because people find it difficult to talk about processes. But they’re really important. Without the targets on the adaptation cycle, we can too easily forget that you need resilient processes to have resilient outcomes.”

The table below, from the same technical report, shows how nearly 10,000 adaptation indicators have been whittled down to a proposed final list of 100. The table also shows how the indicators are split between the themes (9a-g) and iterative adaptation cycle (10a-d) of the GGA framework.

Source: GGA technical report.

Further consultations took place in September and the final workshop under the UAE-Belém work programme took place on 3-4 October.

Following on from the numerous sessions held under the GGA, negotiators are now able to go into COP30 with a consolidated list of indicators to discuss, agree and bring into use, allowing progress towards the adaptation goal in Paris to be finally measured.

What to expect from COP30?

A final decision on the adaptation indicators is expected at COP30, potentially marking a significant milestone under the GGA.

In his third letter, COP30 president-designate Correa do Lago noted that a “special focus” was to be given to the GGA indicators at the summit.

He wrote that adaptation is “the visible face of the global response to climate change” and a “central pillar for aligning climate action with sustainable development”.

Therefore, he said COP30 should focus on “delivering tangible benefits for societies, ecosystems and economies by advancing and concluding the key mandates in this agenda”. These “key mandates” are the GGA and the related topic of National Adaptation Plans (NAPs).

Correa do Lago’s letter added:

“There is a window of opportunity to define a robust framework to track collective progress on adaptation. This milestone will also lay the groundwork for the future of the adaptation agenda.”

Indeed, adaptation has moved up the political agenda this year, with the topic being discussed during the “climate day” at the UN general assembly in September. This included a “leaders’ dialogue” on the sidelines of the assembly, where Carbon Brief understands that leaders of climate-vulnerable nations pushed for specific adaptation targets.

Elsewhere, nearly three-quarters (73%) of new country climate pledges include adaptation components, further emphasising the increased focus the topic is now receiving.

Despite the increased attention, there are still likely to be challenges at COP30, including the continued fight over finance. This will likely be felt particularly keenly, given that the COP26 commitment to double adaptation finance comes to an end this year.

This was part of the “Glasgow dialogue”, which saw parties commit to “at least double” adaptation finance between 2019 and 2025.

Adade Williams tells Carbon Brief:

“A major expectation [at COP30] is that parties will tackle the gaps in adaptation finance, consider how to link MoI – finance, technology, capacity‐building – with the GGA indicators and possibly set new finance ambitions or roadmaps. The emphasis on MoI means capacity building, data systems, technology transfer and institutional strengthening will gain more traction.”

Adaptation finance was also a key topic during pre-COP meetings in Brasilia in October, with E3G noting that it is a “political litmus test for success in Belém, with vulnerable countries signalling urgency and demanding greater clarity that finance will flow”.

Laughlin tells Carbon Brief that she expects discussions on finance to “dominate in Belém” – in particular, given the legacy of the “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) for climate finance agreed at COP29, which many developing countries were “starkly disappointed” by.

Additionally, there may be challenges around the process of negotiations on the GGA indicators, notes Beauchamp, adding:

“We’ve not agreed yet if it is acceptable to open up text of some indicators [to negotiation]. We have 100 of them and, as a technical expert, on one hand [it] is quite worrying, because changing one term in an indicator can change its entire methodology, right? But, at the same time, there is definitely more work that can be done on the indicators.

“So, are we only keeping indicators that can work or that everybody is happy with now, and then we review the set later, for example, with the review of the UAE framework in 2028? Or do we open the whole Pandora’s box and then we start hashing out some new indicators? That’s the first big challenge parties need to grapple with at COP30.”

Despite the challenges, Mulio Alvarez says she would expect a final list of indicators to be adopted at COP30, even if some change during the negotiation process. She adds:

“The Brazilian presidency knows that this is the biggest negotiated outcome of COP30 and they want it to go through smoothly. The adoption of the list would officially launch the UAE framework so that it can begin to track and guide efforts.”

While agreement on indicators would be seen as a political win at COP30, several experts highlighted that it is only a step towards enabling further adaptation work, with Beauchamp noting that parties “need to see this as an opportunity”.

Laughlin adds:

“Although finalising the indicator list is a core deliverable, it is also important that COP30 makes progress on the next steps for the GGA following COP30, including the expectations for reporting, and regular updates to the indicator list so it keeps up with the latest science.”

What will the GGA mean for vulnerable communities?

COP30 kicks off on 10 November and negotiators are hoping to hit the ground running with the condensed list of indicators to discuss.

There remain key questions about what the GGA could mean for adaptation around the world – in particular, for those most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Mulio Alvarez notes:

“In the short term, the GGA metrics [indicators] will likely paint a very challenging picture of the needs for adaptation. In the medium to long term, we hope the GGA will be embedded in policy planning and implementation – supporting risk assessments, helping identify gaps, driving planning and resources and even unlocking investments.”

Others are more cautious about the potential impact of the GGA, the associated framework and its indicators, in terms of driving real progress for adaptation.

Schipper notes that, while the GGA indicators are welcome from a political perspective, “from a scientific perspective, and I think from a development perspective, I think there’s a sort of a high risk that this ends up making people worse off in the end”.

She adds that the incremental approach currently being taken for adaptation is not working and that the indicators can “at best” show us incremental progress.

Schipper notes that there is a risk that the indicators narrow the approach to adaptation to the extent that they are either ineffective or actually produce maladaptive outcomes. She adds:

“I’m not saying that we should abandon the indicators, but I think it’s important to recognise that this is not enough. This is nowhere near enough.”

Others are more optimistic about the long-term potential of the GGA. Laughlin suggests that the indicators could help build systemic resilience, adding that if they were successfully implemented it could mean adaptation is integrated into national development and planning, “making sure that climate resilience becomes a core part of policymaking”. She says:

“For vulnerable populations, this means moving from a reactive approach to a proactive one – embedding resilience into development planning, restoring ecosystems and empowering local communities.

“The success of the GGA in delivering for vulnerable populations hinges on political will, finance and inclusive governance – many of which are currently lacking.”

Beyond COP30, the GGA framework agreed at COP28 includes a number of overarching targets to help guide countries in developing and implementing their NAPs, although these targets are not quantified.

The targets include countries conducting risk assessments to identify the impact of climate change and areas of particular vulnerability, by 2030. The framework says this would inform a country’s NAP and that “by 2030 all parties have in place” adaptation planning processes or strategies, as shown in the image below.

Adade Williams tells Carbon Brief that if the GGA is “effectively implemented” it could help develop systemic resilience in the long term, helping to address “not just climate hazards but also underlying structural vulnerabilities”. She adds:

“However, this long-term potential depends heavily on the extent of political will, sustained finance and capacity support available to developing countries. Without these, the GGA risks becoming a reporting framework rather than a transformative mechanism for resilience.”

The post Q&A: COP30 could – finally – agree how to track the ‘global goal on adaptation’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: COP30 could – finally – agree how to track the ‘global goal on adaptation’

Greenhouse Gases

Western States Brace for a Uranium Boom as the Nation Looks to Recharge its Nuclear Power Industry

After years of federal efforts to revive nuclear power, old mines are stirring again in Wyoming, Texas and Arizona, while new ones line up for permitting expedited by a Trump executive order.

The U.S. says it wants to revive its atomic power industry, but it barely produces any nuclear fuel.

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change3 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases3 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change1 year ago

Climate Change1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy4 months ago

US Grid Strain, Possible Allete Sale