A controversial way of measuring how much methane warms the planet has stirred debate in recent years – particularly around assessing the climate impact of livestock farming.

The metric – known as GWP* (global warming potential star) – was designed to more precisely account for the warming impact of short-lived greenhouse gases, such as methane.

No country so far has used GWP* to measure emissions, but New Zealand is currently considering its use.

In June, a group of climate scientists from around the world wrote an open letter advising against this.

They argued that the metric “creates the expectation that current high levels of methane emissions are allowed to continue”.

Climate experts tell Carbon Brief that there is “no strong debate” on the science behind GWP* and that it can accurately assess the global warming effect of methane.

But many experts also firmly caution against its use in national climate targets, believing it could allow countries to prolong high levels of emissions at a time when they should be drastically cut.

Some researchers tell Carbon Brief that GWP* is an “accounting trick” and a “get-out-of-jail-free card for methane emitters”. A 2021 Bloomberg article called the metric “fuzzy methane math”.

Prof Myles Allen, one of the scientists who created GWP*, tells Carbon Brief that the metric is “nothing more” than one way of better understanding the climate impact of different actions as part of efforts to limit warming under the Paris Agreement.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief explains the science behind GWP*, why the metric is so divisive and the ways in which its use has been considered.

- What is GWP*?

- What are the main controversies around using GWP*?

- Do any countries currently use GWP* to measure methane emissions?

- What do experts think about the use of GWP*?

What is GWP*?

Global warming is caused by a build up of greenhouse gases – mainly from burning fossil fuels – trapping heat in the atmosphere.

Different gases cause differing levels of warming and remain in the atmosphere for varying lengths of time. For example, carbon dioxide (CO2), the main contributor to warming, lingers for centuries, whereas other gases last decades or even millennia.

To account for these variables, scientists use a metric known as global warming potential (GWP), which assesses the warming caused by different gases compared to CO2, which has a GWP of 1.

Using GWP, emissions of other gases are calculated in terms of their “CO2 equivalent” over a given amount of time.

In their reports, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) set out three GWP variants measured over 20 years (GWP20), 100 years (GWP100) and 500 years (GWP500).

GWP100 is the most common approach and is used to calculate emissions under the Paris Agreement.

Methane is a short-lived gas that only remains in the atmosphere for around 12 years before breaking down. But it causes a large burst of initial warming that is around 80 times more powerful than CO2, according to the IPCC.

This means that one tonne of methane causes the same amount of warming as around 80 tonnes of CO2, when measured over a period of 20 years.

When calculated over 100 years, methane’s shorter lifetime means it causes around 30 times more warming than CO2.

Some experts have criticised the use of GWP100, saying it does not sufficiently account for the fact that methane leaves the atmosphere much more quickly than CO2 and does not actually last for 100 years. This is the issue that GWP* was designed to fix.

GWP* calculates the warming contributions of long- and short-lived gases at different rates, accounting for their varying lifetimes in the atmosphere.

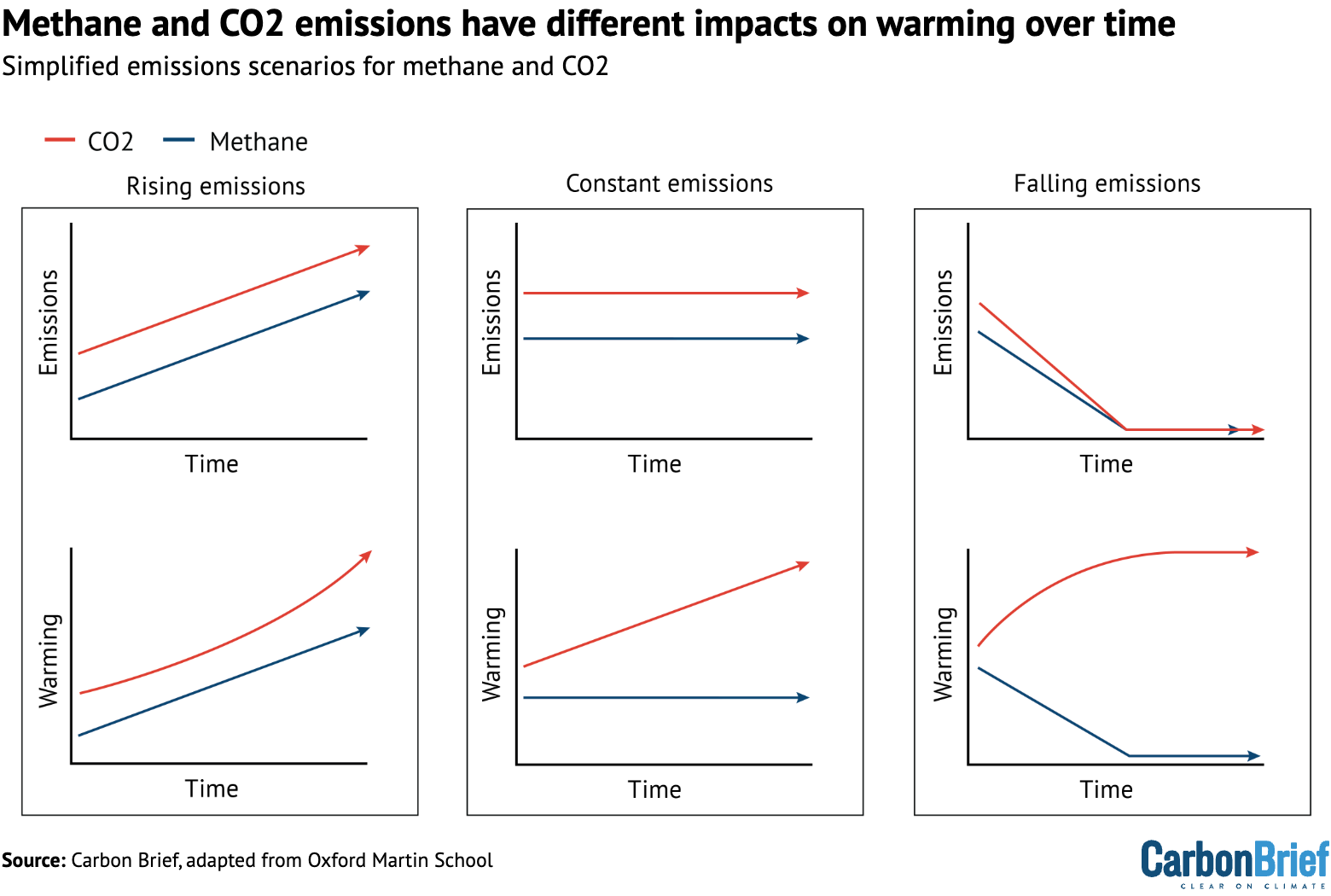

One of the researchers behind GWP*, Dr Michelle Cain, explained in a 2018 Carbon Brief guest post that a constant rate of methane emissions can maintain stable atmospheric concentrations of the gas, assuming methane sinks remain constant as well.

In contrast, a constant rate of CO2 emissions “leads to year-on-year increases in warming, because the CO2 accumulates in the atmosphere”, Cain wrote. CO2 does not leave the atmosphere after a decade or so, as methane does, and continues to build over time until emissions stop.

Cain, formerly a researcher at the University of Oxford and now a senior lecturer at Cranfield University, added:

“For countries with high methane emissions – due to, say, agriculture – this can make a huge difference to how their progress in emission reductions is judged.”

Methane emissions that slowly decline or remain stable over time are calculated as contributing “no additional warming” to the planet, which is not the case with other GWP calculations.

The chart below shows simplified emissions scenarios for CO2 and methane, highlighting the different impacts they have on global warming over time.

The chart below shows how using the two different metrics – GWP* and GWP100 – affects the same emissions pathway throughout the 21st century, given the different warming impacts of greenhouse gases.

If, for example, a country emitted 4m tonnes of methane annually from 1990-2005, these emissions would now be considered “climate-neutral” using GWP*, as they are not actively contributing new warming to the atmosphere, but rather maintaining the existing levels of methane in the atmosphere in 1990.

This would not be the case under GWP100, which looks at the warming potential of emissions over the course of a century and does not account for their different atmospheric lifetimes.

GWP* can be used for other short-lived gases, such as some hydrofluorocarbons, but methane is the most significant short-lived gas when it comes to climate change.

The IPCC notes that converting methane emissions into CO2 equivalent using GWP100 “overstates the effect of constant methane emissions on global surface temperature by a factor of 3-4” and understates the impact of new methane emissions “by a factor of 4-5 over the 20 years following the introduction of the new source”.

GWP* was created by several researchers, including Prof Myles Allen, the head of atmospheric, oceanic and planetary physics at the University of Oxford. The concept was detailed in a 2016 study and first named in a 2018 study. It was further updated by the authors in 2019 and 2020.

Allen tells Carbon Brief that the researchers involved were “reluctant” to give their new metric a name, as it “was just a way of using reported numbers to calculate warming impact”. He adds:

“I think it’s really unfortunate that people have latched onto GWP*. It doesn’t matter. We could forget about GWP* entirely, we can just use a climate model to work out the warming impact…GWP* is a handy way of calculating the warming impact of activities. Nothing more.”

What are the main controversies around using GWP*?

Efforts to cut methane emissions are widely viewed as a “quick-win” to help limit the effects of climate change in the short term.

More than 100 countries signed a pledge, launched at COP26 in 2021, to cut global methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

Cutting methane would also help to counteract an acceleration in warming due to declining aerosol emissions, which are currently masking around half a degree of warming.

Experts Carbon Brief spoke to agree on the importance of cutting methane emissions, but disagree on whether GWP* helps or hinders these efforts.

The debate around the metric centres on the possible impacts of its use, rather than the soundness of the science behind it.

Prof Joeri Rogelj, a climate science and policy professor at Imperial College London, explains:

“At the global level, at any level, the method of GWP* actually provides a good, new way to translate the trajectory of methane emissions into equivalent emissions of CO2, or emissions of CO2 that would have an equivalent warming effect…The debate is on the application.”

Allen says he is a “little frustrated” that discussions around the use of GWP* have “become so emotive”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Every action we take has both a temporary impact on global temperature and a permanent one. How much is in both areas depends on the action. We need to know those two things in order to make decisions about choices of action in pursuit of a temperature goal…GWP* gives you a handy way of doing that.”

Below, Carbon Brief details some of the main discussion points and controversies around GWP*.

Carbon cycle

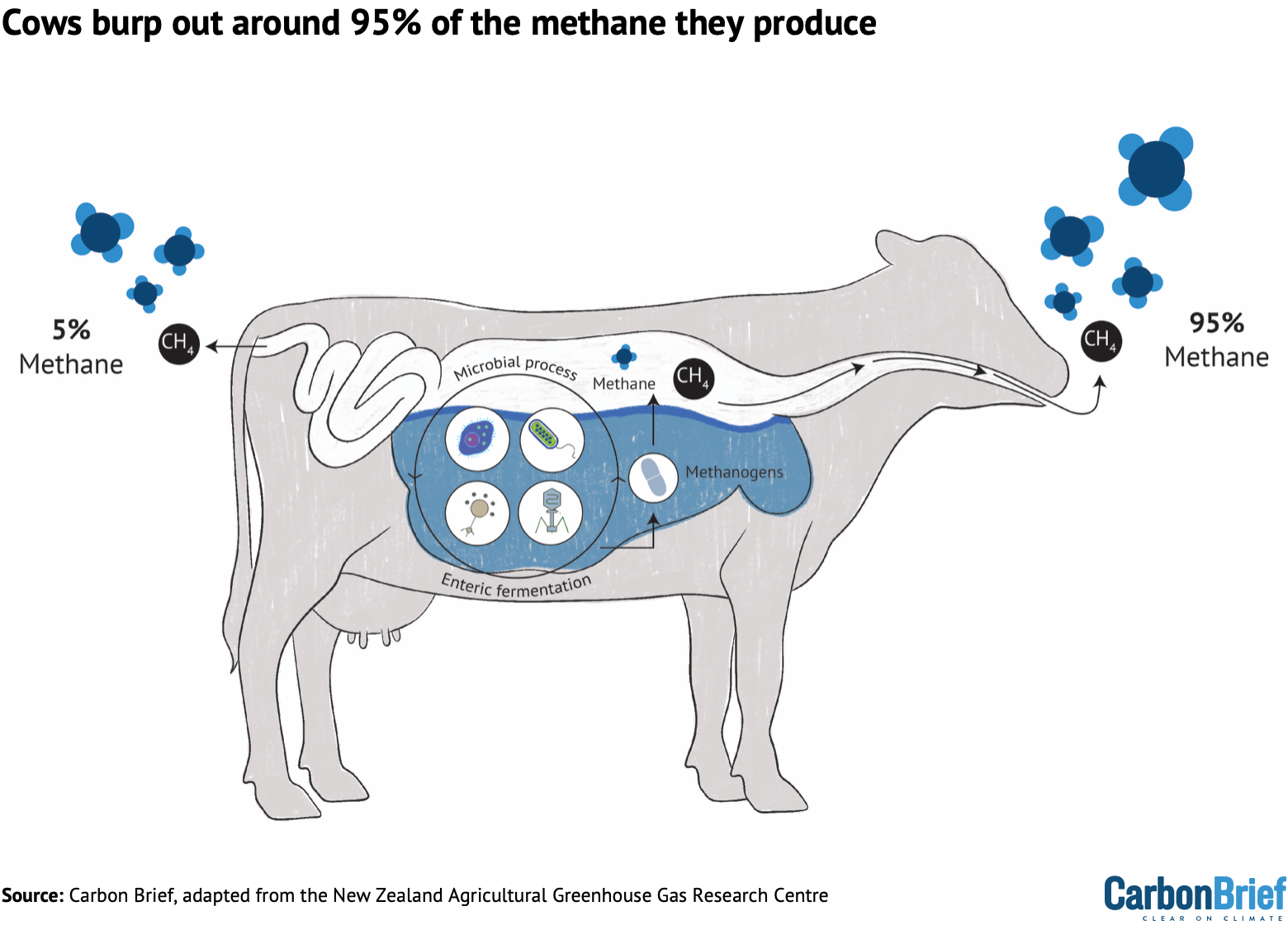

A misleading claim frequently made about livestock is that cows do not contribute much to global warming because the methane they emit eventually returns to the land through the carbon cycle – the set of processes in which carbon is exchanged between the atmosphere, land and ocean, as well as the organisms they contain.

Those in favour of using GWP* to measure methane emissions often also stress the difference between methane emissions that come from animals – known as biogenic methane – and methane from fossil fuels.

Rogelj tells Carbon Brief that biogenic and fossil-sourced methane are “slightly different, but that difference is really second-order” when it comes to climate change.

Methane warms the planet while it is in the atmosphere, so the “climate effect is exactly the same, irrespective of which source the methane comes from”, Rogelj adds.

The differences become more significant when methane breaks down in the atmosphere and oxidises into water vapour and CO2.

CO2 that originated from a cow can be reabsorbed by plants and the land. But the CO2 resulting from fossil methane – which stems from sources such as flaring from oil and gas drilling – stays in the atmosphere. Although fossil methane has a “bit of a longer effect”, Rogelj says:

“This is a bit of a red herring, because the main effect is, of course, the effect that the methane has while it is methane and not what the carbon molecule of that methane has after [the] methane has been broken down or oxidised to CO2.”

He adds that there are ways of reducing agricultural methane, such as “diet change” or “management measures”, but no way to remove the emissions “100%”.

The graphic below shows the digestive process through which a cow emits methane.

Agriculture also causes other significant environmental harms. It is responsible for around 80% of global deforestation and is a key driver of biodiversity loss and water pollution.

Prof Frank Mitloehner, a professor and air-quality specialist at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis), is one of the main proponents of GWP*, frequently speaking about it in public presentations and discussions with the farming sector.

He tells Carbon Brief that, while animal agriculture can cause environmental harm, it is a “silly argument” to say these impacts are being ignored in carbon-cycle discussions.

He gives an example of discussions on deaths from car accidents excluding mentions of the emissions from cars, saying that these wider impacts are still important and can be discussed separately.

He adds that it is an “urban myth” that biogenic methane emissions are not a concern because of the carbon cycle.

‘No additional warming’

Under GWP*, methane emissions stop causing new warming once they reduce by 10% over the course of 30 years – around 3% each decade, or 0.3% each year.

These emissions are then described in research and policy as causing “no additional warming”.

For example, a 2021 study from Mitloehner and other UC Davis researchers, found that methane emissions from the US cattle industry “have not contributed additional warming since 1986”, based on GWP* calculations. It also said that the dairy industry in California “will approach climate neutrality” by the 2030s, if methane emissions are cut by just 1% annually.

(According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, methane emissions from enteric fermentation – the digestive process through which cows produce the greenhouse gas – increased by more than 5% over 1990-2022.)

However, many critics take issue with the “no additional warming” concept.

The main criticism is that, although a gradually reducing herd of cattle may stabilise methane emissions, it still emits the polluting gas. If animal numbers were instead drastically reduced, this would cut methane emissions and lower warming rather than maintaining current levels.

Dr Caspar Donnison, a postdoctoral researcher at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the US, says the term no additional warming is “absolutely misleading” in the context of GWP*. He tells Carbon Brief:

“You just assume, on the face of it, that this means it has a neutral impact on the climate…But ‘no additional warming’ means that you’re still sustaining the warming that the herd is causing.”

Allen says that the debate focuses on the “stock of warming versus additional warming”. He compares it to accounting for historical emissions of CO2:

“If a country got rich by burning CO2, they’ve caused a lot of warming in the past. If they reduce their CO2 emissions to zero, then people are generally happy to call what they’re doing climate-neutral, even though they may be sitting on a huge heap of historical warming caused by their CO2 emissions while they were burning [fossil fuels].

“And yet, temperature-wise, that’s exactly the same thing as having a source of methane that’s declining by 3% per decade.”

Climate ambition

Another criticism around the use of GWP* is that countries or companies with high agricultural methane emissions could use the metric to make small emission reductions appear larger.

Dr Donal Murphy-Bokern, an independent agricultural and environmental scientist, believes that the metric can be used as a “get-out-of-jail-free card for methane emitters”. He adds:

“It’s all about saying carry on as we are; we’ll manage this by slightly reducing our emissions over a critical period in history, so as to appear at that critical period in history to be so-called ‘climate-neutral’.”

Mitloehner disagrees with this, noting that, while reductions in methane emissions appear significant under GWP*, increases also appear significant. He says:

“It is simply not true that GWP* is a get-out-of-jail-free card. It’s not. If you reduce emissions, it makes your contributions look less. If you increase emissions, it makes your contributions much worse.”

Rogelj says he has not seen GWP* being used to advocate for the “highest possible ambition” in cutting methane emissions.

However, Allen says that “no metric tells you what to do”. He adds:

“How you measure emissions and how you measure warming has absolutely no bearing on whether you think a country has an obligation to undo some of the damage to the climate they’ve caused in the past.

“This is where the ‘free-pass’ argument makes no sense to me, because the existence of a method to calculate the warming impact of your emissions allows you to make decisions about emissions in light of their warming impact, sure, but it doesn’t tell you what the outcomes of those decisions should be.”

Allen adds that the livestock sector is “unsustainable globally”, with animal numbers and methane levels still rising.

The chart below shows how atmospheric methane concentrations have increased in recent decades.

Allen tells Carbon Brief:

“Do we need to eliminate livestock agriculture to stop global warming? No…[but] we do need to start decreasing it. And if we can decrease it faster than 3% per decade then that would help reduce warming that’s caused by other sectors or, indeed, undo some of the warming that the livestock sector has caused in the past.”

Mitloehner says considerations on the fairness of using GWP* are “real from a policy standpoint and they have to be addressed from a policy standpoint”. He adds:

“But, from a scientific standpoint – and that’s where I’m coming from – I think it’s not controversial.”

Baseline and historical emissions

The baseline year from which emissions reduction targets are set is significant, as it helps form the scope of climate ambition.

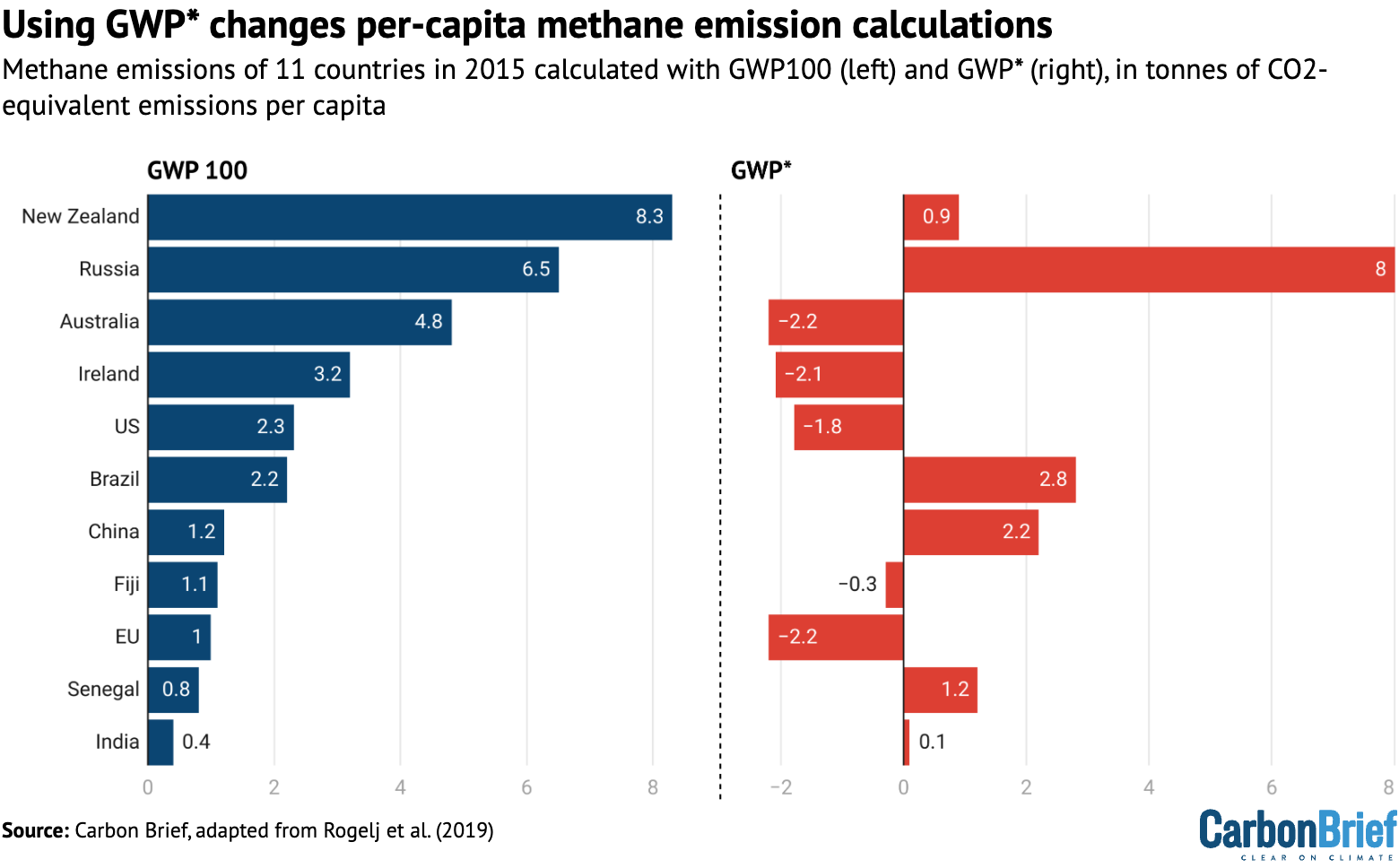

For example, high-emitting countries, such as the UK, have set 1990 as their baseline year for emissions-cutting targets, whereas many low-emitting countries may choose further back or more recent years, depending on their needs. Rogelj says:

“Because GWP* translates a change in emissions into either an instantaneous emission or instantaneous removal of CO2, your starting point becomes really important.

“If you start with very high emissions of methane and you did not in any way account for this high starting point, then even very minor, unambitious reductions in methane would result in creating credits for high-polluting countries.”

However, he notes that this is just one way of applying the metric and that there could be ways to avoid this “inequitable outcome”, such as applying GWP* globally and allocating each country a per-capita methane budget, instead of assessing based on national current or past emissions. (Rogelj and Prof Carl-Friedrich Schleussner discussed other possible GWP* equity measures in a 2019 study.)

The chart below, adapted from that study, shows how GWP* can significantly change the per-capita methane emissions of different countries. Some countries with high agricultural methane emissions, such as New Zealand, change from high to low per-capita emitters.

A 2025 study used a climate model to quantify future national warming contributions for Ireland under different emissions scenarios and found that “no additional warming” approaches, such as GWP*, are “not a robust basis for fair and effective national climate policy”.

Discussing baseline concerns, Allen says these considerations are the same for any other metric:

“It depends on how much account you want to take of [the] warming you’ve caused in the past – and at what point you want to take responsibility for the warming your actions had caused.”

He believes that most climate experts agree that it is good to understand the impact emissions have on global temperatures, but “where the controversy arises is about what you consider someone’s nominal emissions to be today”. He adds:

“This is where everybody gets upset, because if you use GWP*, then a livestock sector that’s reducing its emissions by 3% per decade – which most global-north livestock sectors are doing – it looks like their emissions are quite small.

“But that’s only a problem if you think that the main issue is working out whose fault global warming is, rather than working out what we should do about it.”

Communication

Many experts Carbon Brief spoke to took issue with how GWP* has been discussed by some of its proponents.

Murphy-Bokern criticises how Mitloehner and other experts communicate the metric. He says:

“The confusion arises from the activities of Mitloehner, in particular, where he presents the farming community – and the industry in general – with the idea that you can magic away the warming effect of methane simply by looking at the rate of change of methane emissions.”

Mitloehner says he has no regrets about his communication of GWP*, adding that he has “always emphasised to the livestock sector that reductions of methane are important”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“I’m proud because I have been able to take the livestock sector along with the understanding that reductions are needed and that they can be part of a solution if they understand that.”

The New York Times reported in 2022 that the research centre led by Mitloehner at the University of California, Davis “receives almost all its funding from industry donations and coordinates with a major livestock lobby group on messaging campaigns”. Other reports note his discussions about GWP* with stakeholders in various countries.

In response to these reports, Mitloehner says he believes it is important to work with the sector you are researching, adding that he receives both public and private funding. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The problem is not that they [the meat industry] are investing in research and communications and extension. The problem is that they are not putting in enough, because the public sector is withdrawing from this.

“Climate research is being slashed…If the government is not paying into research to quantify and reduce emissions – and those people who are critical of what we do say ‘oh, industry shouldn’t do it’ – then, I ask you, who should?”

Colin Woodall, the chief executive of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, a US lobby group, said in 2022 that GWP* is the “methodology we need to make sure everybody is utilising in order to tell the true story of methane”, Unearthed reported. According to the outlet, he added:

“We’re working with our partners around the globe to ensure that everybody is working towards adoption of GWP*.”

Asked if he regrets anything about his communication of GWP*, Allen tells Carbon Brief:

“When we first introduced this – and, perhaps, this is one thing I do regret – I was, perhaps, a little naive in that I thought everybody would seize on focusing on [the] warming impact because it was, from a policy perspective, potentially much easier for the agricultural sector.

“I thought that this would actually be welcomed. But, sadly, it’s not been. And I think part of that is because of this narrative of blame.”

Do any countries currently use GWP* to measure methane emissions?

GWP* is not yet used by any country in methane emission reporting or targets. But it has been considered by New Zealand, Ireland and other nations with high agricultural emissions.

A 2024 statement from dozens of NGOs and environmental organisations called for countries and companies not to use GWP* in their greenhouse gas reporting or to guide their climate mitigation policies. They wrote:

“The risks of GWP* significantly outweigh the benefits.”

New Zealand

New Zealand is currently considering changing its biogenic methane target, including applying the “no additional warming” approach used in GWP*. If it does so, it could become the first country to adopt GWP*.

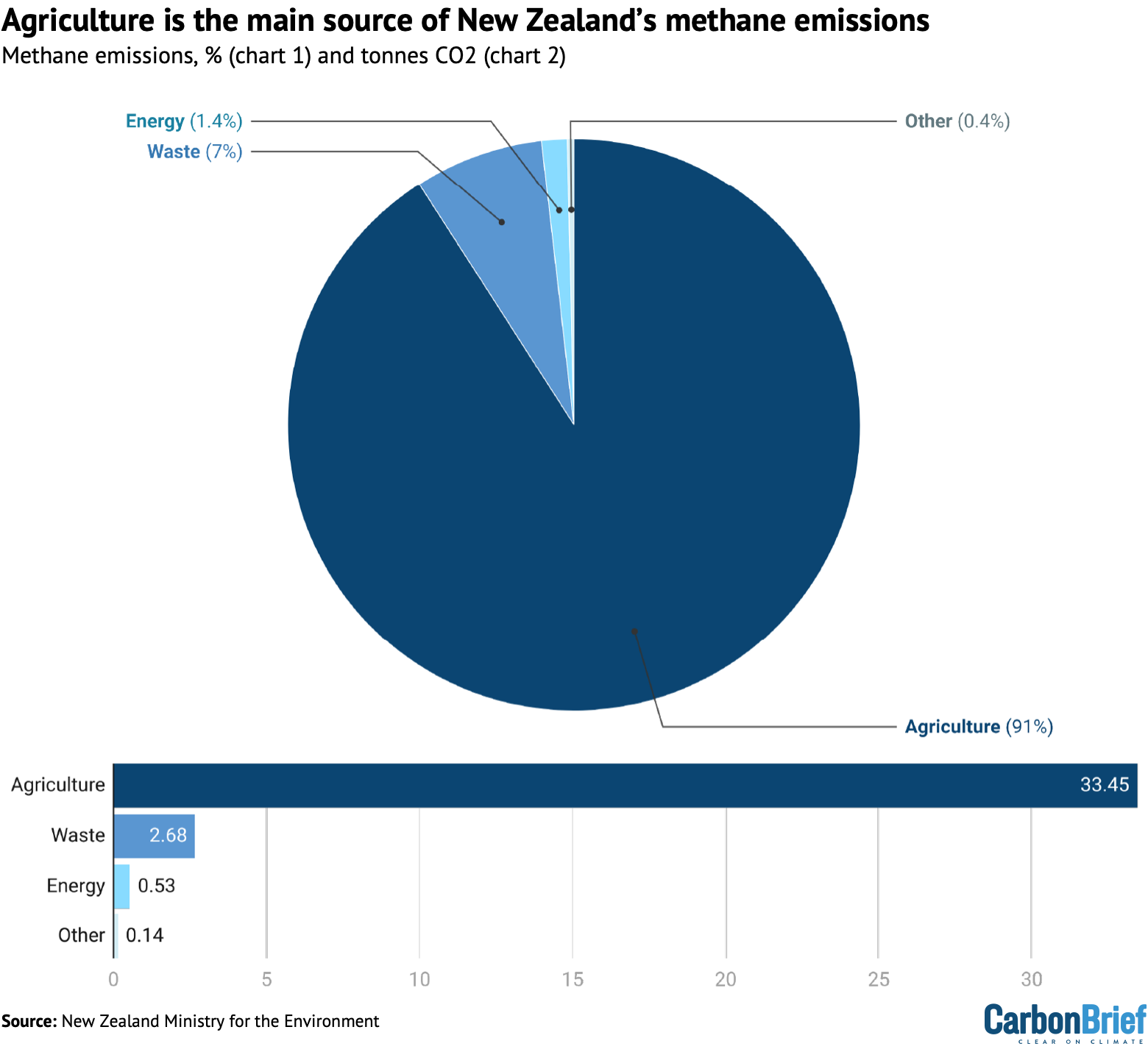

The nation is a major livestock producer and agriculture generates nearly half of all its greenhouse gas emissions.

The chart below shows that the agricultural sector is also responsible for more than 90% of the country’s methane emissions.

New Zealand has a legally binding target to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. However, biogenic methane has separate targets to reduce by 10% by 2030 and by 24-47% by 2050, compared to a baseline of 2017 levels.

In late 2024, a review from the nation’s Climate Change Commission recommended that the government change its 2050 greenhouse gas targets, including to increase the biogenic methane goal to a 35-47% reduction by 2050.

At the same time, an independent panel commissioned by the New Zealand government reviewed how the country’s climate targets would look under the “no additional warming” approach.

The resulting report, which did not look specifically at GWP*, but used a similar concept, found that a 14-15% cut in biogenic methane by 2050 would be “consistent with meeting the ‘no additional warming’ condition”, under mid-range global emissions scenarios that keep temperatures below 2C.

The government is “currently considering” these findings, a spokesperson for the Ministry for the Environment tells Carbon Brief in a statement.

The spokesperson says that the report is “part of the body of evidence” that the government will use in its response to the Climate Change Commission’s review, which it must publish by November 2025.

Cain, the Cranfield University lecturer who co-created GWP*, wrote in Climate Home News in 2019 that New Zealand reducing biogenic methane by 24% would “offset the warming impact” of the rest of the country’s emissions, adding:

“New Zealand could declare itself climate-neutral almost immediately, well before 2050 and only because farmers were reducing their methane emissions. That’s a free pass to all the other sectors, courtesy of New Zealand’s farmers.”

A report on GWP* by the Changing Markets Foundation found that, in 2020, 16 industry groups in New Zealand and the UK “urged” the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to use GWP* to assess warming impacts.

Australia

The Guardian reported in May 2024 that Cattle Australia, a cattle producer trade group, was “lobbying the red-meat sector to ditch its net-zero target in favour of a ‘climate-neutral’ goal that would require far more modest reductions in methane emissions”.

Cattle Australia’s senior adviser and former chief executive, Dr Chris Parker, tells Carbon Brief in a statement that the organisation is “working with the Australian government to ensure methane emissions within the biogenic carbon cycle are appropriately accounted for in our national accounting systems”. He adds:

“We believe GWP* offers a more accurate way of assessing methane’s temporary place in the atmosphere and its impact on the climate. Australian cattle producers are part of the climate solution and we need policy settings to enable them to participate in carbon markets.”

Australia’s Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water did not respond to Carbon Brief’s request for comment.

Ireland

Internal documents assessed for the Changing Markets Foundation’s GWP* report “suggest” that Ireland’s Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine has advocated for GWP* “at the international level”, including at the UN’s COP26 climate summit in 2021.

Allen and Mitloehner were involved in a 2022 Irish parliamentary discussion on methane, in which Allen advocated for the country to “be a policy pioneer” by using GWP* in its methane reporting alongside standard methods.

The country’s coalition government, formed earlier this year, pledged to “recognise the distinct characteristics of biogenic methane” and also “advocate for the accounting of this greenhouse gas to be re-classified at EU and international level”.

A spokesperson for Ireland’s Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine tells Carbon Brief that this does not refer to using GWP* specifically. They say the country is “in favour of using accurate, scientifically validated and internationally accepted emission measurement metrics”, adding:

“It is important that the nature of how biogenic methane interacts in the environment is accurately reflected in how it is accounted for. This does not mean the use of the metric GWP*.”

In December 2024, Ireland’s Climate Change Advisory Council proposed temperature neutrality pathway options to the government that do not specifically refer to GWP*, but use the same concept of no “additional warming”.

The Irish Times reported that this was “in part to reduce potential disruption from Ireland’s legal commitment to achieve national ‘climate neutrality’ by 2050”.

The climate and energy minister, Darragh O’Brien, said he has “not formed a definitive view” on this, the newspaper noted, and that expert views will feed into ongoing discussions on the 2031-40 carbon budgets, which are due to be finalised later in 2025.

In an Irish Times opinion article, Prof Hannah Daly from University College Cork, described the temperature neutrality consideration as “one of the most consequential climate decisions this government will make”. She wrote that the approach “amounts to a free pass for continued high emissions” of livestock methane.

Paraguay

Paraguay mentioned GWP* in a national submission to the UN in 2023 after agribusiness representatives “pushed” to adopt the metric, according to Consenso, a Paraguayan online newsletter.

The country’s National Directorate of Climate Change told Consenso for a separate article related to GWP* that it is “aware” of questions around the metric, but that it “has the option of using other measurement systems” for emissions reporting.

UK

The National Farmers’ Union, the main farming representative group in England and Wales, is in favour of using GWP* to measure agricultural methane emissions.

Carbon Brief understands that the UK government is not currently considering using GWP* in addition to, or instead of, GWP100 in its emissions reporting.

What do experts think about the use of GWP*?

Most experts Carbon Brief spoke to agreed that GWP* could be a useful metric to apply to global methane emissions, but that it is difficult to apply equitably in individual countries or sectors. Rogelj believes that are are some contexts in which GWP* could be used, but adds:

“You cannot just take targets that were set and discussed historically with one greenhouse gas metric in mind – GWP100 under the UNFCCC [United Nations Framework on Climate Change] and the Paris Agreement and all that – [and] then simply apply a different metric to it. They change meaning entirely.

“So, if one would like to use GWP*, one should build the policy targets and frameworks from the ground up to take advantage of the strengths of that metric, but also put in place safeguards that ensure that the weaknesses and limitations of that metric do not result in unfair or undesirable outcomes.”

A 2022 study says that using GWP* in climate plans “would ask countries to start from scratch in terms of their political target setting processes”, calling it a “bold ask” for policymakers.

It adds that achieving net-zero emissions, as measured with GWP*, “would only lead to a stabilisation of temperatures at their peak level”.

However, a 2024 study found that GWP* gives a “dynamic” assessment of the warming impact of emissions that “better aligns with temperature goals” than GWP100, when measuring methane emissions from agriculture.

Allen believes that criticism over the use of GWP* is similar to “saying it’s a meaningless question” to consider the warming impact of a country or company’s actions. He adds:

“That seems a very strange position to me, because we need to know how different activities are contributing to global warming because we have a temperature target.

“In saying GWP* is a bad thing, what people are actually saying is it’s a bad thing to know the warming impact of our actions, which is a very strange thing to say.”

He says that such metrics help countries to make informed decisions on climate action, but that “we can’t expect metrics to make these decisions for us”.

Murphy-Bokern notes that GWP* could be useful in modelling global, rather than national, methane emissions to avoid high-emitting countries making small methane cuts to achieve “no additional warming”, rather than significantly reducing these emissions.

He says the metric would be particularly useful if global emissions were close to zero, as a way to target the final remaining emissions. But, he adds:

“We are so far away from that very happy situation, that the discussion now with GWP* is a huge distraction from the key objective, which is to reduce emissions.”

Mitloehner – and every expert Carbon Brief spoke with – agrees with this wider point. He says:

“The main point is we need to reduce emissions. In the case of livestock, we need to reduce methane emissions. And the question is how do we get it done? And how do we quantify the impacts that [that reduction] would have accurately and fairly? The other issues are issues that politicians have to answer.”

The post Q&A: What the ‘controversial’ GWP* methane metric means for farming emissions appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: What the ‘controversial’ GWP* methane metric means for farming emissions

Climate Change

DeBriefed 9 January 2026: US to exit global climate treaty; Venezuelan oil ‘uncertainty’; ‘Hardest truth’ for Africa’s energy transition

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

US to pull out from UNFCC, IPCC

CLIMATE RETREAT: The Trump administration announced its intention to withdraw the US from the world’s climate treaty, CNN reported. The move to leave the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in addition to 65 other international organisations, was announced via a White House memorandum that states these bodies “no longer serve American interests”, the outlet added. The New York Times explained that the UNFCCC “counts all of the other nations of the world as members” and described the move as cementing “US isolation from the rest of the world when it comes to fighting climate change”.

MAJOR IMPACT: The Associated Press listed all the organisations that the US is exiting, including other climate-related bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). The exit also means the withdrawal of US funding from these bodies, noted the Washington Post. Bloomberg said these climate actions are likely to “significantly limit the global influence of those entities”. Carbon Brief has just published an in-depth Q&A on what Trump’s move means for global climate action.

Oil prices fall after Venezuela operation

UNCERTAIN GLUT: Global oil prices fell slightly this week “after the US operation to seize Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro created uncertainty over the future of the world’s largest crude reserves”, reported the Financial Times. The South American country produces less than 1% of global oil output, but it holds about 17% of the world’s proven crude reserves, giving it the potential to significantly increase global supply, the publication added.

TRUMP DEMANDS: Meanwhile, Trump said Venezuela “will be turning over” 30-50m barrels of oil to the US, which will be worth around $2.8bn (£2.1bn), reported BBC News. The broadcaster added that Trump claims this oil will be sold at market price and used to “benefit the people of Venezuela and the US”. The announcement “came with few details”, but “marked a significant step up for the US government as it seeks to extend its economic influence in Venezuela and beyond”, said Bloomberg.

Around the world

- MONSOON RAIN: At least 16 people have been killed in flash floods “triggered by torrential rain” in Indonesia, reported the Associated Press.

- BUSHFIRES: Much of Australia is engulfed in an extreme heatwave, said the Guardian. In Victoria, three people are missing amid “out of control” bushfires, reported Reuters.

- TAXING EMISSIONS: The EU’s landmark carbon border levy, known as “CBAM”, came into force on 1 January, despite “fierce opposition” from trading partners and European industry, according to the Financial Times.

- GREEN CONSUMPTION: China’s Ministry of Commerce and eight other government departments released an action plan to accelerate the country’s “green transition of consumption and support high-quality development”, reported Xinhua.

- ACTIVIST ARRESTED: Prominent Indian climate activist Harjeet Singh was arrested following a raid on his home, reported Newslaundry. Federal forces have accused Singh of “misusing foreign funds to influence government policies”, a suggestion that Singh rejected as “baseless, biased and misleading”, said the outlet.

- YOUR FEEDBACK: Please let us know what you thought of Carbon Brief’s coverage last year by completing our annual reader survey. Ten respondents will be chosen at random to receive a CB laptop sticker.

47%

The share of the UK’s electricity supplied by renewables in 2025, more than any other source, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Latest climate research

- Deforestation due to the mining of “energy transition minerals” is a “major, but overlooked source of emissions in global energy transition” | Nature Climate Change

- Up to three million people living in the Sudd wetland region of South Sudan are currently at risk of being exposed to flooding | Journal of Flood Risk Management

- In China, the emissions intensity of goods purchased online has dropped by one-third since 2000, while the emissions intensity of goods purchased in stores has tripled over that time | One Earth

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The US, which has announced plans to withdraw from the UNFCCC, is more responsible for climate change than any other country or group in history, according to Carbon Brief analysis. The chart above shows the cumulative historical emissions of countries since the advent of the industrial era in 1850.

Spotlight

How to think about Africa’s just energy transition

African nations are striving to boost their energy security, while also addressing climate change concerns such as flood risks and extreme heat.

This week, Carbon Brief speaks to the deputy Africa director of the Natural Resource Governance Institute, Ibrahima Aidara, on what a just energy transition means for the continent.

Carbon Brief: When African leaders talk about a “just energy transition”, what are they getting right? And what are they still avoiding?

Ibrahima Aidara: African leaders are right to insist that development and climate action must go together. Unlike high-income countries, Africa’s emissions are extremely low – less than 4% of global CO2 emissions – despite housing nearly 18% of the world’s population. Leaders are rightly emphasising universal energy access, industrialisation and job creation as non-negotiable elements of a just transition.

They are also correct to push back against a narrow narrative that treats Africa only as a supplier of raw materials for the global green economy. Initiatives such as the African Union’s Green Minerals Strategy show a growing recognition that value addition, regional integration and industrial policy must sit at the heart of the transition.

However, there are still important blind spots. First, the distributional impacts within countries are often avoided. Communities living near mines, power infrastructure or fossil-fuel assets frequently bear environmental and social costs without sharing in the benefits. For example, cobalt-producing communities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or lithium-affected communities in Zimbabwe and Ghana, still face displacement, inadequate compensation, pollution and weak consultation.

Second, governance gaps are sometimes downplayed. A just transition requires strong institutions (policies and regulatory), transparency and accountability. Without these, climate finance, mineral booms or energy investments risk reinforcing corruption and inequality.

Finally, leaders often avoid addressing the issue of who pays for the transition. Domestic budgets are already stretched, yet international climate finance – especially for adaptation, energy access and mineral governance – remains far below commitments. Justice cannot be achieved if African countries are asked to self-finance a global public good.

CB: Do African countries still have a legitimate case for developing new oil and gas projects, or has the energy transition fundamentally changed what ‘development’ looks like?

IA: The energy transition has fundamentally changed what development looks like and, with it, how African countries should approach oil and gas. On the one hand, more than 600 million Africans lack access to electricity and clean cooking remains out of reach for nearly one billion people. In countries such as Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal and Tanzania, gas has been framed to expand power generation, reduce reliance on biomass and support industrial growth. For some contexts, limited and well-governed gas development can play a transitional role, particularly for domestic use.

On the other hand, the energy transition has dramatically altered the risks. Global demand uncertainty means new oil and gas projects risk becoming stranded assets. Financing is shrinking, with many development banks and private lenders exiting fossil fuels. Also, opportunity costs are rising; every dollar locked into long-lived fossil infrastructure is a dollar not invested in renewables, grids, storage or clean industry.

Crucially, development today is no longer just about exporting fuels. It is about building resilient, diversified economies. Countries such as Morocco and Kenya show that renewable energy, green industry and regional power trade can support growth without deepening fossil dependence.

So, the question is no longer whether African countries can develop new oil and gas projects, but whether doing so supports long-term development, domestic energy access and fiscal stability in a transitioning world – or whether it risks locking countries into an extractive model that benefits few and exposes countries to future shocks.

CB: What is the hardest truth about Africa’s energy transition that policymakers and international partners are still unwilling to confront?

IA: For me, the hardest truth is this: Africa cannot deliver a just energy transition on unfair global terms. Despite all the rhetoric, global rules still limit Africa’s policy space. Trade and investment agreements restrict local content, industrial policy and value-addition strategies. Climate finance remains fragmented and insufficient. And mineral supply chains are governed largely by consumer-country priorities, not producer-country development needs.

Another uncomfortable truth is that not every “green” investment is automatically just. Without strong safeguards, renewable energy projects and mineral extraction can repeat the same harms as fossil fuels: displacement, exclusion and environmental damage.

Finally, there is a reluctance to admit that speed alone is not success. A rushed transition that ignores governance, equity and institutions will fail politically and socially, and, ultimately, undermine climate goals.

If Africa’s transition is to succeed, international partners must accept African leadership, African priorities and African definitions of development, even when that challenges existing power dynamics in global energy and mineral markets.

Watch, read, listen

CRISIS INFLAMED: In the Brazilian newspaper Folha de São Paulo, columnist Marcelo Leite looked into the climate impact of extracting more oil from Venezuela.

BEYOND TALK: Two Harvard scholars argued in Climate Home News for COP presidencies to focus less on climate policy and more on global politics.

EU LEVIES: A video explainer from the Hindu unpacked what the EU’s carbon border tax means for India and global trade.

Coming up

- 10-12 January: 16th session of the IRENA Assembly, Abu Dhabi

- 13-15 January: Energy Security and Green Infrastructure Week, London

- 13-15 January: The World Future Energy Summit, Abu Dhabi

- 15 January: Uganda general elections

Pick of the jobs

- WRI Polsky Energy Center, global director | Salary: around £185,000. Location: Washington DC; the Hague, Netherlands; New Delhi, Mumbai, or Bengaluru, India; or London

- UK government Advanced Research and Invention Agency, strategic communications director – future proofing our climate and weather | Salary: £115,000. Location: London

- The Wildlife Trusts, head of climate and international policy | Salary: £50,000. Location: London

- Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, senior manager for climate | Salary: Unknown. Location: London, UK

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 9 January 2026: US to exit global climate treaty; Venezuelan oil ‘uncertainty’; ‘Hardest truth’ for Africa’s energy transition appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Melting Ground: Why Permafrost Matters for Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples

When people discuss climate change, most envision melting glaciers, smoke-filled skies from wildfires, or hurricanes ravaging coastlines. However, another crisis is unfolding in Canada’s North, one that is quieter but just as perilous: the melting of permafrost.

Permafrost is ground that has remained frozen for at least two years, though in many places, it has been frozen for thousands of years. It is a mix of soil, rock, and ice, and it covers almost half of Canada’s landmass, particularly in the Arctic. Think of it like the Earth’s natural deep freezer. Inside it are ancient plants, animal remains, and vast amounts of carbon that have been trapped and locked away for millennia.

As long as the permafrost stays frozen, those gases remain contained. But now, as temperatures rise and the Arctic warms nearly four times faster than the global average, that freezer door is swinging wide open.

Why the Arctic Matters to Everyone

It might be tempting to think of the Arctic as far away, remote, untouched, or disconnected from daily life in southern Canada. But the reality is that what happens in the Arctic affects everyone. Permafrost contains almost twice as much carbon as is currently in the Earth’s atmosphere. When it melts, that carbon escapes in the form of carbon dioxide and methane, two of the most potent greenhouse gases.

This creates a dangerous cycle: warmer air melts permafrost, which releases greenhouse gases, and those gases in turn contribute to even greater warming of the Earth. Scientists refer to this as a “feedback loop.” If large amounts of permafrost thaw, the gases released could overwhelm even the strongest climate policies, making it almost impossible to slow global warming.

The ripple effects are already visible. Melting permafrost worsens heatwaves in Ontario, intensifies wildfires in Alberta and British Columbia, and fuels stronger Atlantic storms. Rising global temperatures also bring increased insurance premiums, higher food prices, and strained infrastructure due to new climate extremes. The Arctic may be far north, but it is the beating heart of global climate stability.

Impacts Close to Home in Canada

For northern communities, the impacts of melting permafrost are immediate and deeply personal. Buildings, schools, and homes that were once stable on frozen foundations are cracking and sinking. Road’s twist and buckle, airstrips become unsafe, and pipelines leak as the ground beneath them shifts. This is not just inconvenient; it is life-threatening, as these systems provide access to food, medical care, and basic supplies in places already cut off from southern infrastructure.

The hamlet of Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories, sits on the edge of the Arctic Ocean. As the permafrost beneath it thaws, the coastline is collapsing at an alarming rate of several meters each year. Entire homes have already been moved inland, and Elders warn that parts of the community may disappear into the sea within a generation. For residents, this is not just about losing land but losing ancestral ties to a place that has always been home.

In Inuvik, Northwest Territories, traditional underground ice cellars, once reliable food storage systems for generations, are collapsing into the permafrost. Families now face soaring costs to ship in groceries; undermining food security and cultural practices tied to country food.

Even the transportation routes that connect the North to the South are threatened. In the Yukon, the Dempster Highway, Canada’s only all-season road to the Arctic coast, is buckling as thawing permafrost destabilizes its foundation. Engineers are racing to repair roads that were never designed for melting ground, costing governments tens of millions of dollars each year.

And the South is not spared. The carbon released from permafrost melt contributes to the greenhouse gases driving climate extremes across Canada, including hotter summers in Toronto, devastating wildfires in Kelowna, severe flooding along the St. Lawrence, and worsening droughts on the Prairies. What melts in the North shapes life everywhere else.

Why Permafrost is Sacred in Indigenous Worldviews

For Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic, permafrost is not just frozen soil; it is a living part of their homeland and identity. Inuit, First Nations, and Métis Peoples have lived in relationship with frozen ground for thousands of years. The permafrost preserves sacred sites, traditional travel routes, and hunting lands. It has long been a source of stability, shaping the balance of ecosystems and making possible the cultural practices that sustain communities.

For Inuit in particular, permafrost has always been a trusted partner in food security. Ice cellars dug into the ground kept caribou, seal, fish, and whale meat fresh throughout the year. This practice is not only efficient and sustainable but also deeply cultural, tying families to cycles of harvest and sharing. As the permafrost melts and these cellars collapse, Inuit food systems are being disrupted. Families must rely more heavily on expensive store-bought food, which undermines both health and cultural sovereignty.

The thaw also threatens sacred spaces. Burial grounds are being disturbed, rivers and lakes are shifting, and the plants and animals that communities depend on are disappearing. In Indigenous worldviews, the land is kin alive and relational. When the permafrost melts, it signals not just an environmental crisis but a breaking of relationships that have been nurtured since time immemorial.

The Human Face of Melting Permafrost

The impacts of permafrost melt cannot be measured solely in terms of carbon emissions or financial costs. They must also be seen in the daily lives of the people who call the North home. In some communities, houses tilt and become uninhabitable, forcing residents to relocate, which disrupts family life, education, and mental health. In others, health centres and schools need constant repair, straining already limited budgets.

Travel across the land, once a predictable and safe experience, is now risky. Snowmobiles break through thinning ice. Trails flood or erode unexpectedly. Hunters face danger simply by trying to continue practices that have sustained their people for millennia.

For many Indigenous families, this is not only about the loss of infrastructure but also the loss of identity. When permafrost thaws, so do the practices tied to it: storing food, travelling safely, caring for burial sites, and teaching youth how to live in balance with the land. These changes erode culture, language, and ways of knowing that are inseparable from place.

Why the World Should Pay Attention

The melting of permafrost is not just a northern problem it is a global alarm bell. Scientists estimate that if even a fraction of the carbon stored in permafrost is released, it could equal the emissions from decades of current human activities. This is enough to derail international climate targets and lock the planet into a state of runaway warming.

This matters for everyone. Rising seas will not stop at Canada’s borders; they will flood coastal cities around the globe. Droughts and crop failures will disrupt food supplies and drive-up prices worldwide. Heatwaves will claim more lives in cities already struggling to keep cool. Economic costs will skyrocket, from insurance payouts to rebuilding disaster-hit communities. If the permafrost continues to thaw unchecked, the climate shocks of the past decade will look mild compared to what lies ahead.

But beyond the science, there is also a moral responsibility. The Arctic has contributed the least to climate change yet is suffering some of its most significant impacts. Indigenous communities, which have lived sustainably for generations, are now bearing the brunt of global emissions. For the world to ignore this crisis is to accept an injustice that will echo through history.

The Arctic is often referred to as the “canary in the coal mine” for climate change, but it is more than a warning system; it is a driver of global stability. If we lose the permafrost, we risk losing the fight against climate change altogether. Paying attention to what is happening in the Arctic is not optional. It is a test of whether humanity can listen, learn, and act before it is too late.

Moving Forward: Responsibility and Action

Addressing permafrost melt means tackling climate change at its root: cutting greenhouse gas emissions and transitioning to renewable energy. Canada must lead in reducing its dependence on oil and gas while investing in clean energy and climate-resilient infrastructure. But technical fixes alone are not enough. Indigenous-led monitoring, adaptation, and governance must be supported and prioritized.

In Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, Indigenous guardians and community researchers are already combining traditional knowledge with Western science to track permafrost thaw, monitor wildlife, and pilot new forms of housing built for unstable ground. These projects demonstrate that solutions are most effective when they originate from the individuals most closely connected to the land.

For families in southern Canada, the issue may seem distant. However, the truth is that every decision matters. The energy we use, the food we waste, and the products we buy all contribute to the warming that melts permafrost. By reducing consumption, supporting Indigenous-led initiatives, and advocating for robust climate policies, households far from the Arctic can still play a role in protecting it.

The permafrost is melting. It is reshaping the Arctic, altering Canada, and posing a threat to global climate stability. However, it also offers us a choice: to continue down a path of denial, or to act guided by science, led by Indigenous knowledge, and rooted in care for the generations to come.

Blog by Rye Karonhiowanen Barberstock

Image Credit : Alin Gavriliuc, Unsplash

The post Melting Ground: Why Permafrost Matters for Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples appeared first on Indigenous Climate Hub.

Melting Ground: Why Permafrost Matters for Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples

Climate Change

Q&A: What Trump’s US exit from UNFCCC and IPCC could mean for climate action

The Trump administration in the US has announced its intention to withdraw from the UN’s landmark climate treaty, alongside 65 other international bodies that “no longer serve American interests”.

Every nation in the world has committed to tackling “dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system” under the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

During Donald Trump’s second presidency, the US has already failed to meet a number of its UN climate treaty obligations, including reporting its emissions and funding the UNFCCC – and it has not attended recent climate summits.

However, pulling out of the UNFCCC would be an unprecedented step and would mark the latest move by the US to disavow global cooperation and climate action.

Among the other organisations the US plans to leave is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN body seen as the global authority on climate science.

In this article, Carbon Brief considers the implications of the US leaving these bodies, as well as the potential for it rejoining the UNFCCC in the future.

Carbon Brief has also spoken to experts about the contested legality of leaving the UNFCCC and what practical changes – if any – will result from the US departure.

- What is the process for pulling out of the UNFCCC?

- Is it legal for Trump to take the US out of the UNFCCC unilaterally?

- How could the US rejoin the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement?

- What changes when the US withdraws from the UNFCCC?

- What about the US withdrawal from the IPCC?

- What other organisations are affected?

What is the process for pulling out of the UNFCCC?

The Trump administration set out its intention to withdraw from the UNFCCC and the IPCC in a White House presidential memorandum issued on 7 January 2026.

It claims authority “vested in me as president by the constitution and laws of the US” to withdraw the country from the treaty, along with 65 other international and UN bodies.

However, the memo includes a caveat around its instructions, stating:

“For UN entities, withdrawal means ceasing participation in or funding to those entities to the extent permitted by law.”

(In an 8 January interview with the New York Times, Trump said he did not “need international law” and that his powers were constrained only by his “own morality”.)

The US is the first and only country in the world to announce it wants to withdraw from the UNFCCC.

The convention was adopted at the UN headquarters in New York in May 1992 and opened for signatures at the Rio Earth summit the following month. The US became the first industrialised nation to ratify the treaty that same year.

It was ultimately signed by every nation on Earth – making it one of the most ratified global treaties in history.

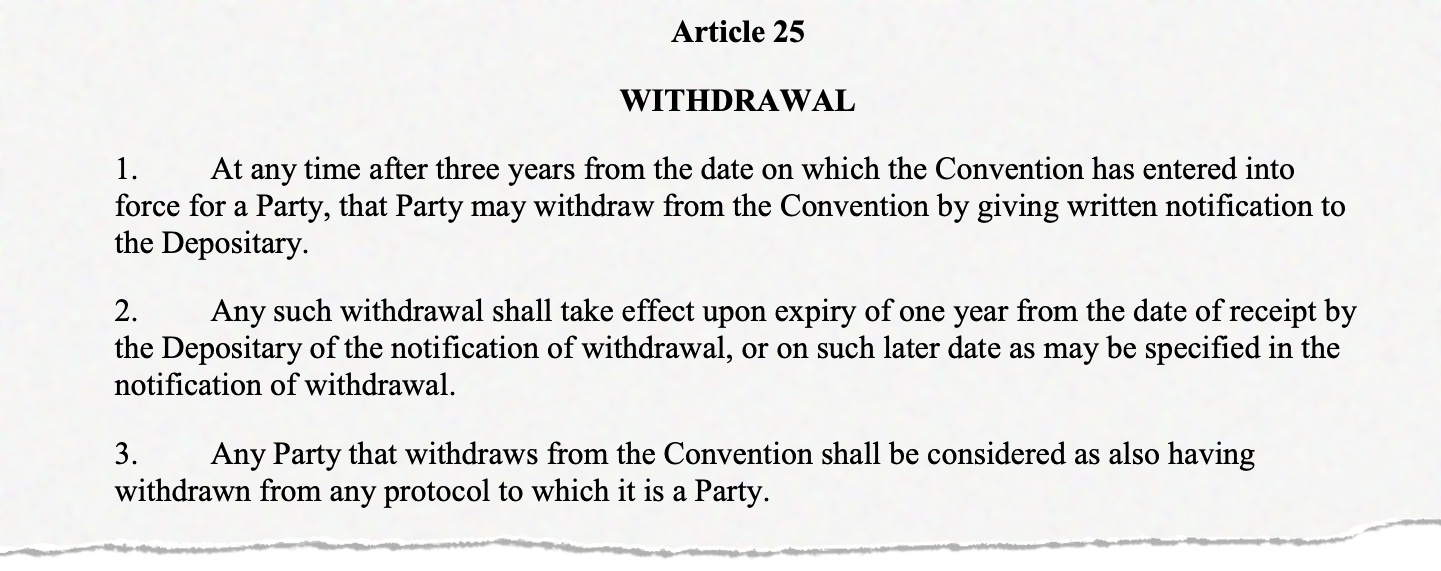

Article 25 of the treaty states that any party may withdraw by giving written notification to the “depositary”, which is elsewhere defined as being the UN secretary general – currently, António Guterres.

The article, shown below, adds that the withdrawal will come into force a year after a written notification is supplied.

The treaty adds that any party that withdraws from the convention shall be considered as also having left any related protocol.

The UNFCCC has two main protocols: the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 and the Paris Agreement of 2015.

Although former US president Bill Clinton signed the Kyoto Protocol in 1998, its formal ratification faced opposition from the Senate and the treaty was ultimately rejected by his successor, president George W Bush, in 2001.

Domestic opposition to the protocol centred around the exclusion of major developing countries, such as China and India, from emissions reduction measures.

The US did ratify the Paris Agreement, but Trump signed an executive order to take the nation out of the pact for a second time on his first resumed day in office in January 2025.

Is it legal for Trump to take the US out of the UNFCCC unilaterally?

Whether Trump can legally pull the US out of the UNFCCC without the consent of the Senate remains unclear.

The US previously left the Paris Agreement during Trump’s first term.

Both the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement allow any party to withdraw with a year’s written notice. However, both treaties state that parties cannot withdraw within the first three years of ratification.

As such, the first Trump administration filed notice to exit the Paris Agreement in November 2019 and became the first nation in the world to formally leave a year later – the day after Democrat Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election.

On his first day in office in 2021, Biden rejoined the Paris Agreement. This took 30 days from notifying the UNFCCC to come into force.

The legalities of leaving the UNFCCC are murkier, due to how it was adopted.

As Michael B Gerrard, director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School, explains to Carbon Brief, the Paris Agreement was ratified without Senate approval.

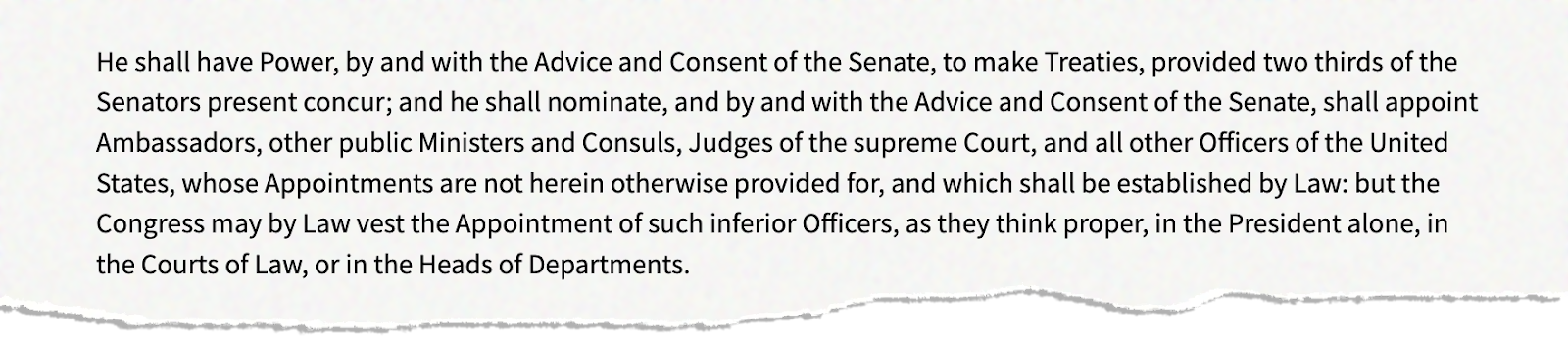

Article 2 of the US Constitution says presidents have the power to make or join treaties subject to the “advice and consent” of the Senate – including a two-thirds majority vote (see below).

However, Barack Obama took the position that, as the Paris Agreement “did not impose binding legal obligations on the US, it was not a treaty that required Senate ratification”, Gerrard tells Carbon Brief.

As noted in a post by Jake Schmidt, a senior strategic director at the environmental NGO Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), the US has other mechanisms for entering international agreements. It says the US has joined more than 90% of the international agreements it is party to through different mechanisms.

In contrast, George H Bush did submit the UNFCCC to the Senate in 1992, where it was unanimously ratified by a 92-0 vote, ahead of his signing it into law.

Reversing this is uncertain legal territory. Gerrard tells Carbon Brief:

“There is an open legal question whether a president can unilaterally withdraw the US from a Senate-ratified treaty. A case raising that question reached the US Supreme Court in 1979 (Goldwater vs Carter), but the Supreme Court ruled this was a political question not suitable for the courts.”

Unlike ratifying a treaty, the US Constitution does not explicitly specify whether the consent of the Senate is required to leave one.

This has created legal uncertainty around the process.

Given the lack of clarity on the legal precedent, some have suggested that, in practice, Trump can pull the US out of treaties unilaterally.

Sue Biniaz, former US principal deputy special envoy for climate and a key legal architect of the Paris Agreement, tells Carbon Brief:

“In terms of domestic law, while the Supreme Court has not spoken to this issue (it treated the issue as non-justifiable in the Goldwater v Carter case), it has been US practice, and the mainstream legal view, that the president may constitutionally withdraw unilaterally from a treaty, ie without going back to the Senate.”

Additionally, the potential for Congress to block the withdrawal from the UNFCCC and other treaties is unclear. When asked by Carbon Brief if it could play a role, Biniaz says:

“Theoretically, but politically unlikely, Congress could pass a law prohibiting the president from unilaterally withdrawing from the UNFCCC. (The 2024 NDAA contains such a provision with respect to NATO.) In such case, its constitutionality would likely be the subject of debate.”

How could the US rejoin the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement?

The US would be able to rejoin the UNFCCC in future, but experts disagree on how straightforward the process would be and whether it would require a political vote.

In addition to it being unclear whether a two-thirds “supermajority” vote in the Senate is required to leave a treaty, it is unclear whether rejoining would require a similar vote again – or if the original 1992 Senate consent would still hold.

Citing arguments set out by Prof Jean Galbraith of the University of Pennsylvania law school, Schmidt’s NRDC post says that a future president could rejoin the convention within 90 days of a formal decision, under the merit of the previous Senate approval.

Biniaz tells Carbon Brief that there are “multiple future pathways to rejoining”, adding:

“For example, Prof Jean Galbraith has persuasively laid out the view that the original Senate resolution of advice and consent with respect to the UNFCCC continues in effect and provides the legal authority for a future president to rejoin. Of course, the Senate could also give its advice and consent again. In any case, per Article 23 of the UNFCCC, it would enter into force for the US 90 days after the deposit of its instrument.”

Prof Oona Hathaway, an international law professor at Yale Law School, believes there is a “very strong case that a future president could rejoin the treaty without another Senate vote”.

She tells Carbon Brief that there is precedent for this based on US leaders quitting and rejoining global organisations in the past, explaining:

“The US joined the International Labour Organization in 1934. In 1975, the Ford administration unilaterally withdrew, and in 1980, the Carter administration rejoined without seeking congressional approval.

“Similarly, the US became a member of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1946. In the 1980s, the Reagan administration unilaterally withdrew the US. The Bush administration rejoined UNESCO in 2002, but in 2019 the Trump administration once again withdrew. The Biden administration rejoined in 2023, and the Trump Administration announced its withdrawal again in 2025.”

But this “legal theory” of a future US president specifically re-entering the UNFCCC “based on the prior Senate ratification” has “never been tested in court”, Prof Gerrard from Columbia Law School tells Carbon Brief.

Dr Joanna Depledge, an expert on global climate negotiations and research fellow at the University of Cambridge, tells Carbon Brief:

“Due to the need for Senate ratification of the UNFCCC (in my interpretation), there is no way back now for the US into the climate treaties. But there is nothing to stop a future US president applying [the treaty] rules or – what is more important – adopting aggressive climate policy independently of them.”

If it were required, achieving Senate approval to rejoin the UNFCCC would take a “significant shift in US domestic politics”, public policy professor Thomas Hale from the University of Oxford notes on Bluesky.

Rejoining the Paris Agreement, on the other hand, is a simpler process that the US has already undertaken in recent years. (See: Is it legal for Trump to take the US out of the UNFCCC unilaterally?) Biniaz explains:

“In terms of the Paris Agreement, a party to that agreement must also be a party to the UNFCCC (Article 20). Assuming the US had rejoined the UNFCCC, it could rejoin the Paris Agreement as an executive agreement (as it did in early 2021). The agreement would enter into force for the US 30 days after the deposit of its instrument (Article 21).”

The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, an environmental non-profit, explains that Senate approval was not required for Paris “because it elaborates an existing treaty” – the UNFCCC.

What changes when the US withdraws from the UNFCCC?

US withdrawal from the UNFCCC has been described in media coverage as a “massive hit” to global climate efforts that will “significantly limit” the treaty’s influence.

However, experts tell Carbon Brief that, as the Trump administration has already effectively withdrawn from most international climate activities, this latest move will make little difference.

Moreover, Depledge tells Carbon Brief that the international climate regime “will not collapse” as a result of US withdrawal. She says:

“International climate cooperation will not collapse because the UNFCCC has 195 members rather than 196. In a way, the climate treaties have already done their job. The world is already well advanced on the path to a lower-carbon future. Had the US left 10 years ago, it would have been a serious threat, but not today. China and other renewable energy giants will assert even more dominance.”

Depledge adds that while the “path to net-zero will be longer because of the drastic rollback of domestic climate policy in the US”, it “won’t be reversed”.

Technically, US departure from the UNFCCC would formally release it from certain obligations, including the need to report national emissions.

As the world’s second-largest annual emitter, this is potentially significant.

“The US withdrawal from the UNFCCC undoubtedly impacts on efforts to monitor and report global greenhouse gas emissions,” Dr William Lamb, a senior researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), tells Carbon Brief.

Lamb notes that while scientific bodies, such as the IPCC, often use third-party data, national inventories are still important. The US already failed to report its emissions data last year, in breach of its UNFCCC treaty obligations.

Robbie Andrew, senior researcher at Norwegian climate institute CICERO, says that it will currently be possible for third-party groups to “get pretty close” to the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions estimates previously published by the US administration. However, he adds:

“The further question, though, is whether the EIA [US Energy Information Administration] will continue reporting all of the energy data they currently do. Will the White House decide that reporting flaring is woke? That even reporting coal consumption is an unnecessary burden on business? I suspect the energy sector would be extremely unhappy with changes to the EIA’s reporting, but there’s nothing at the moment that could guarantee anything at all in that regard.”

Andrew says that estimating CO2 emissions from energy is “relatively straightforward when you have detailed energy data”. In contrast, estimating CO2 emissions from agriculture, land use, land-use change and forestry, as well as other greenhouse gas emissions, is “far more difficult”.

The US Treasury has also announced that the US will withdraw from the UN’s Green Climate Fund (GCF) and give up its seat on the board, “in alignment” with its departure from the UNFCCC. The Trump administration had already cancelled $4bn of pledged funds for the GCF.

Another specific impact of US departure would be on the UNFCCC secretariat budget, which already faces a significant funding gap. US annual contributions typically make up around 22% of the body’s core budget, which comes from member states.

However, as with emissions data and GCF withdrawal, the Trump administration had previously indicated that the US would stop funding the UNFCCC.

In fact, billionaire and UN special climate envoy Michael Bloomberg has already committed, alongside other philanthropists, to making up the US shortfall.

Veteran French climate negotiator Paul Watkinson tells Carbon Brief:

“In some ways the US has already suspended its participation. It has already stopped paying its budget contributions, it sent no delegation to meetings in 2025. It is not going to do any reporting any longer – although most of that is now under the Paris Agreement. So whether it formally leaves the UNFCCC or not does not change what it is likely to do.”

Dr Joanna Depledge tells Carbon Brief that she agrees:

“This is symbolically and politically huge, but in practice it makes little difference, given that Trump had already announced total disengagement last year.”

The US has a history of either leaving or not joining major environmental treaties and organisations, such as the Paris Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol. (See: What is the process for pulling out of the UNFCCC?)

Dr Jennifer Allan, a global environmental politics researcher at Cardiff University, tells Carbon Brief:

“The US has always been an unreliable partner…Historically speaking, this is kind of more of the same.”

The NRDC’s Jake Schmidt tells Carbon Brief that he doubts US absence will lead to less progress at UN climate negotiations. He adds:

“[The] Trump team would have only messed things up, so not having them participate will probably actually lead to better outcomes.”

However, he acknowledges that “US non-participation over the long-term could be used by climate slow-walking countries as an excuse for inaction”.

Biniaz tells Carbon Brief that the absence of the US is unlikely to unlock reform of the UN climate process – and that it might make negotiations more difficult. She says:

“I don’t see the absence of the US as promoting reform of the COP process. While the US may have had strong views on certain topics, many other parties did as well, and there is unlikely to be agreement among them to move away from the consensus (or near consensus) decision-making process that currently prevails. In fact, the US has historically played quite a significant ‘broker’ role in the negotiations, which might actually make it more difficult for the remaining parties to reach agreement.”

After leaving the UNFCCC, the US would still be able to participate in UN climate talks as an observer, albeit with diminished influence. (It is worth noting that the US did not send a delegation to COP30 last year.)

There is still scope for the US to use its global power and influence to disrupt international climate processes from the outside.

For example, last year, the Trump administration threatened nations and negotiators with tariffs and withdrawn visa rights if they backed an International Maritime Organization (IMO) effort to cut shipping emissions. Ultimately, the measures were delayed due to a lack of consensus.

(Notably, the IMO is among the international bodies that the US has not pledged to leave.)

What about the US withdrawal from the IPCC?

As a scientific body, rather than a treaty, there is no formal mechanism for “withdrawing” from the IPCC. In its own words, the IPCC is an “organisation of governments that are members of the UN or World Meteorological Organization” (WMO).

Therefore, just being part of the UN or WMO means a country is eligible to participate in the IPCC. If a country no longer wishes to play a role in the IPCC, it can simply disengage from its activities – for example, by not attending plenary meetings, nominating authors or providing financial support.

This is exactly what the US government has been doing since last year.

Shortly before the IPCC’s plenary meeting for member governments – known as a “session” – in Hangzhou, China, in March 2025, reports emerged that US officials had been denied permission to attend.

In addition, the contract for the technical support unit for Working Group III (WG3) was terminated by its provider, NASA, which also eliminated the role of chief scientist – the position held by WG3 co-chair Dr Kate Cavlin.

(Each of the IPCC’s three “working groups” has a technical support unit, or TSU, which provides scientific and operational support. These are typically “co-located” between the home countries of a working group’s two co-chairs.)

The Hangzhou session was the first time that the US had missed a plenary since the IPCC was founded in 1988. It then missed another in Lima, Peru, in October 2025.

Although the US government did not nominate any authors for the IPCC’s seventh assessment cycle (AR7), US scientists were still put forward through other channels. Analysis by Carbon Brief shows that, across the three AR7 working group reports, 55 authors are affiliated with US institutions.

However, while IPCC authors are supported by their institutions – they are volunteers and so are not paid by the IPCC – their travel costs for meetings are typically covered by their country’s government. (For scientists from developing countries, there is financial support centrally from the IPCC.)

Prof Chris Field, co-chair of Working Group II during the IPCC’s fifth assessment (AR5), tells Carbon Brief that a “number of philanthropies have stepped up to facilitate participation by US authors not supported by the US government”.

The US Academic Alliance for the IPCC – a collaboration of US universities and research institutions formed last year to fill the gap left by the government – has been raising funds to support travel.

In a statement reacting to the US withdrawal, IPCC chair Prof Sir Jim Skea said that the panel’s focus remains on preparing the reports for AR7:

“The panel continues to make decisions by consensus among its member governments at its regular plenary sessions. Our attention remains firmly on the delivery of these reports.”

The various reports will be finalised, reviewed and approved in the coming years – a process that can continue without the US. As it stands, the US government will not have a say on the content and wording of these reports.

Field describes the US withdrawal as a “self-inflicted wound to US prestige and leadership” on climate change. He adds:

“I don’t have a crystal ball, but I hope that the US administration’s animosity toward climate change science will lead other countries to support the IPCC even more strongly. The IPCC is a global treasure.”

The University of Edinburgh’s Prof Gabi Hegerl, who has been involved in multiple IPCC reports, tells Carbon Brief:

“The contribution and influence of US scientists is presently reduced, but there are still a lot of enthusiastic scientists out there that contribute in any way they can even against difficult obstacles.”

On Twitter, Prof Jean-Pascal van Ypersele – IPCC vice-chair during AR5 – wrote that the US withdrawal was “deeply regrettable” and that to claim the IPCC’s work is contrary to US interests is “simply nonsensical”. He continued:

“Let us remember that the creation of the IPCC was facilitated in 1988 by an agreement between Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, who can hardly be described as ‘woke’. Climate and the environment are not a matter of ideology or political affiliation: they concern everyone.”

Van Ypersele added that while the IPCC will “continue its work in the service of all”, other countries “will have to compensate for the budgetary losses”.

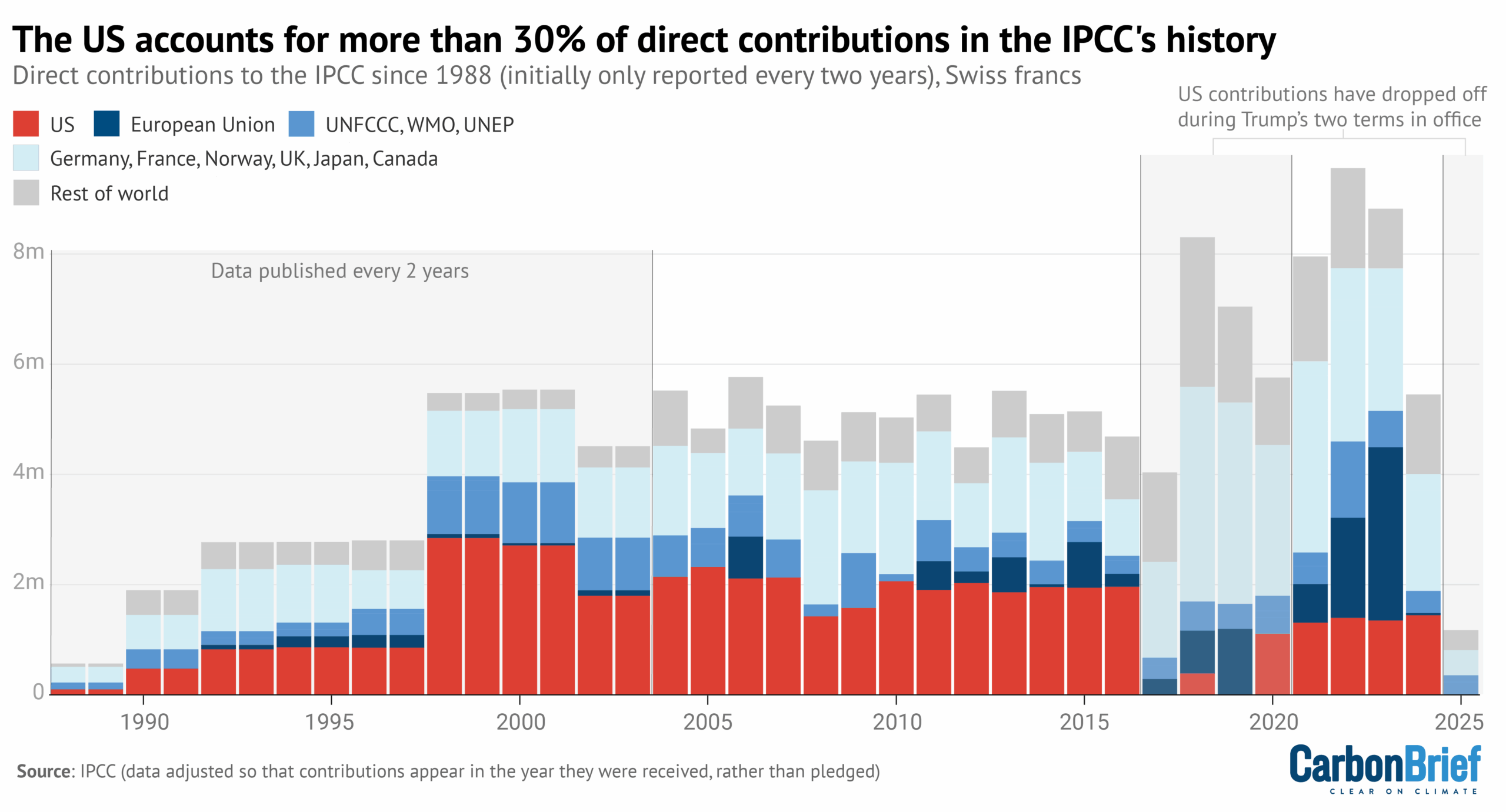

The IPCC’s most recent budget figures show that the US did not make a contribution in 2025.

Carbon Brief analysis shows that the US has provided around 30% of all voluntary contributions in the IPCC’s history. Totalling approximately $67m (£50m), this is more than four times that of the next-largest direct contributor, the EU.

However, this is not the first time that the US has withdrawn funding from the IPCC. During Trump’s first term of office, his administration cut its contributions in 2017, with other countries stepping up their funding in response. The US subsequently resumed its contributions.

At its most recent meeting in Lima, Peru, in October 2025, the IPCC warned of an “accelerating decline” in the level of annual voluntary contributions from countries and other organisations, reported the Earth Negotiations Bulletin. As a result, the IPCC invited member countries to increase their donations “if possible”.

What other organisations are affected?

In addition to announcing his plan to withdraw the US from the UNFCCC and the IPCC, Trump also called for the nation’s departure from 16 other organisations related to climate change, biodiversity and clean energy.

These include:

- The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) – the biodiversity equivalent of the IPCC.

- Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development – a voluntary group of more than 80 countries aiming to make the mining sector more sustainable.

- UN Energy – the principal UN organisation for international collaboration on energy.

- UN Oceans – a UN mechanism responsible for overseeing the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and other UN agencies related to ocean and coastal issues.

- UN Water – the UN agency responsible for water and sanitation.