Extreme weather events, such as heavy rainfall, flooding and heatwaves, have been described as the “new normal” for China.

The country lost almost 12bn yuan ($1.65bn) due to heavy rainfall and floods in April – “the worst in 10 years”. In June, dozens of people were killed and some 33 rivers in China “exceeded warning levels”. The floods in Guilin, capital city of Guangxi province, were the largest in the area since 1998.

It has been less than a year since the Beijing meteorological service recorded 745mm of rain in just five days during July 2023 – roughly the same amount the city usually receives in the whole month.

The province surrounding Beijing, Hebei, also had heavy rainfall at the same time. In July 2023, the county of Lincheng recorded more than one metre of rain, twice its annual average.

In July 2021, Hebei’s neighbouring province Henan had a “one-in-a-thousand-year” rainstorm.

While China has issued more policies to improve its emergency response system and infrastructure, the increasing number of extreme weather events continues to pose challenges.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief looks at the reasons for China’s recent floods, how the country is adapting and whether it will need to re-examine and future-proof its flood defence systems.

- What are the reasons behind the recent floods?

- What role does human-caused climate change play?

- How is China adapting to increasingly frequent flooding?

- How effective are these measures?

- What can China learn from other cities?

What are the reasons behind the recent floods?

There are various factors behind the frequent heavy rain and flooding in recent years.

Dr Oliver Wing, honorary research fellow at the school of geographical sciences, University of Bristol, tells Carbon Brief that “on the whole, we expect a warming world to be a wetter world due to the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship”.

This relationship dictates that the air can generally hold around 7% more moisture for every 1C of temperature rise, meaning rainfall is likely to be heavier in a warmer climate.

Wing notes that “for sub-daily rainfall, we are seeing even greater scaling than this relationship would suggest. This makes surface water flooding in cities [more likely] due to short-duration, intense, localised rainfall increase”.

In addition, he says, “warming is inducing a rise in sea levels in most places, meaning storm surges have a higher baseline from which to inflict damage”.

In China, “higher than normal temperatures” were behind frequent heavy rainfall in southern coastal provinces, such as Guangdong and Guangxi, since April, says Zheng Zhihai, chief forecaster at the National Climate Centre of the China Meteorological Administration (CMA), and reported in China Daily.

Zheng adds that the El Niño-Southern Oscillation – a natural climate cycle that entered its warmer El Niño phase in mid-2023 – was partly to blame because it raised sea surface temperatures and directed vast amounts of water vapour from the South China Sea and the Bay of Bengal towards southern China.

Dr Faith Chan, head of the school of geographical sciences at the University of Nottingham Ningbo China, tells Carbon Brief that the rainfall pattern in Guangdong during this April was quite similar to the intensive rainstorm on 6-8 September in 2023 after Typhoon Haikui.

Specifically, the intense rainfalls were generated by the low-pressure moist current from the south-east and south Asian monsoon pattern crashing into another low-pressure rain belt from the Philippines and the west Pacific.

Typhoon Haikui had hit Hong Kong with the worst storm in 140 years and caused some of the heaviest rains in the provinces of Guangdong and Fujian.

While these intense rainstorms, in a meteorological sense, are not unusual, they are happening more closely to one another owing to the warming world, Chan says.

Large-scale heavy rainstorms typically occur three times on average in April – the onset of a monsoon season. But, this year, China has been battered by at least eight regional extreme rain events in the month alone, all happening in quick succession.

River floods are commonly seen in the affected regions, such as Chongqing and Hunan. Identifying the causes can be more complicated for river floods in general, says Wing:

“There are many modulating factors. Drier soils in a warming world may enable the land to absorb the increased rainfall, thereby mitigating any flood hazard increase. Many floods are not driven by intense rainfall, but are driven by snowmelt or low-intensity, long-duration rain falling on saturated soils. For this reason, it is not reasonable to extrapolate that increased rainfall in a warming world will lead to increased fluvial flooding.”

Chan says natural reasons “of course” enhanced the wetness, “but human-induced climate change led to the greenhouse effect and caused sea temperature to rise, which caused more storms and low-pressure rain belts. That is a fact”.

Wing agrees that “the thermodynamic impact” of human-led climate change increases the rainfall associated with storms. But, he adds:

“What we do not understand well is how anthropogenic climate change has altered the dynamics of the climate system, and where and how this either compounds or dampens the thermodynamic response.”

What role does human-caused climate change play?

Many studies have found that warmer sea surface temperatures are supercharging high-impact, back-to-back extreme rains.

The sixth assessment report (AR6) from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also says that human-induced climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions contributes to ocean warming and “is likely the main driver of the observed global-scale intensification of heavy precipitation over land regions”.

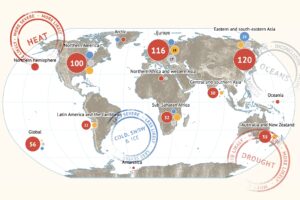

In east and central Asia, under 1.5C of global warming, extreme annual daily rainfall (Rx1) and five-day accumulated rainfall (Rx5) events are projected to increase by 28% and 15%, respectively, relative to 1971-2000, according to AR6.

Similarly, it says that in China’s urban agglomerations, “an increase in global warming from 1.5C to 2C is likely to increase the intensity of total precipitation of very wet days 1.8 times and double maximum five-day precipitation”.

Prof Yang Chen of the Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences at the CMA tells Carbon Brief that human-caused intensification of heavy rainfall over China had been even larger than expected. He explains:

“Human-caused intensification of heavy precipitation over monsoonal China is markedly larger than expected from increases in atmospheric moisture due to warming, because of stronger feedback between latent heat releases and ascending motion within wetter storms in a warmer climate.”

Such feedback, he adds, is particularly evident in eastern China compared to other regions of similar latitudes.

A recent study in Nature also anticipates storm activity over China to become more frequent and intense as a result of warming. By the end of the 21st century, the annual average frequency of tropical cyclones on the east coast of China is anticipated to increase by 16% compared to the present day, according to the study.

Apart from climate change that is caused by human activities, poorly designed and constructed cities, as well as subsidence – caused by groundwater extraction, the weight of buildings as result of urban growth, urban transportation systems and mining activities – could also amplify floods.

Dr Kevin Smiley, assistant professor from the department of sociology of Louisiana State University tells Carbon Brief:

“Climate change is increasing the severity and frequency of extreme weather. Extra rainfall induced by climate change can be the difference between a building’s parking lot hosting puddles on a rainy day compared to floodwaters crossing the threshold of the building and causing thousands of dollars of damages.

“It’s always important to remember: climate change is anthropogenic, so this increased risk also has human-caused roots.”

How is China adapting to increasingly frequent flooding?

China has built a number of large water projects to prevent flooding, such as the south-north water transfer projects in the Yangtze river that was launched in 2002.

In the most recent “national water network construction planning outline” published by the State Council – China’s top administrative authority, the equivalent of central government – constructing “national water networks” by 2035 is among the “backbones” of future flood prevention.

The “backbones” in the document also include large hard-engineered structures on the main rivers, such as embankments, flood gates and channelised river networks, to mitigate flood risks.

Meanwhile, a study published in the journal Ocean & Coastal Management found that “nature-based solutions” have also become popular in China. The restoration and conservation of freshwater swamps, mangroves and wetlands along coastlines and river mouths are being used to provide a buffer for tidal and storm surges.

They include the Chongming Island wetland in Shanghai (Yangtze delta) and the Futian and Mai Po wetlands in Shenzhen Bay (Pearl River delta).

Another concept proposed in the planning document is to “accelerate smart development” by using the internet, data and technology to monitor and prevent floods.

The capital Beijing has incorporated data from high-definition cameras, as well as telescopes, radar maps and satellite cloud images to provide real-time hazard updates, which has improved emergency response times.

Ningbo, a port city on China’s east coast, has worked with mobile companies to analyse big data and disseminate information.

The Ministry of Emergency Management said these measures have reduced the number of deaths and missing people as a result of natural disasters by 54% over 2018-22, compared to 2013-17. The death toll continued to fall in 2023 but the number of destroyed buildings and direct economic losses rose by 97% and 13%, respectively, compared with 2018-22 levels.

In 2015, the sponge city programme (SCP) concept was written into a policy document of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. It was promoted across the country and 30 major cities, such as Wuhan (home to 11 million people) and Zhengzhou (home to 10 million people), were chosen to be the pilot cities.

Those sponge cities are designed to collect, purify and re-use at least 70% of the floodwaters through “green-blue facilities”, such as green roofs, permeable pavements and stormwater parks, in urban areas. The overall system was meant to resolve the issues of urban heating, freshwater scarcity and flooding all at once.

China has improved its recovery process too. In Ningbo, for example, flood victims were able to access financial compensation within an hour, using an improved online documentation process during Typhoon In-Fa in 2021.

How effective are these measures?

Chan tells Carbon Brief that China has “done very well in terms of preparation, response and recovery for flood and drought hazards” – the two most destructive types of natural disasters.

“As a global south country,” he says, referring to China as a developing country, “China has done quite well with the SCP [sponge cities programme] and the ecologically enhanced solutions for addressing climate change”.

However, Wing argues that nature-based solutions, such as SCP, can “get saturated quickly” and so “there’s a risk of their role being overstated”. He continues:

“These types of interventions are most effective for rainfall events which occur relatively regularly at low intensities. They will be quickly overwhelmed during the very intense, rare rainfall events (whose probabilities are changing rapidly in a warming world) that cause the most damage and suffering.”

In 2021, a “historically rare” rain and flood, that affected more than 14 million people and killed 398 in Zhengzhou, a showcase sponge city, highlighted the limitations of the SCP in the face of climate change.

SCP is designed to only withstand one-in-30-year rain events, says the Nature study. On top of that, it can create a false sense of security, which encourages more people to move to high-risk areas, leading to an increase in population and assets in exposed areas that require ever-increasing protection in a cycle referred to as a “levee effect”, says Chan.

The levee effect refers to the paradox whereby the construction of a flood-defence levee leads to a lowered perception of flood risks and a greater likelihood of property owners investing in their property, increasing the potential damages should the levee breach.

The effect, according to the Nature paper, is a key challenge in the densely populated Yellow River delta and Pearl River areas, which both face high risks of flooding.

Smiley says:

“Risk is realised when social vulnerabilities intersect with hazards. Vulnerabilities are social. Flood impacts are greater when social vulnerabilities are greater…Social vulnerabilities are uneven. A household with some wealth and good insurance can recover from a flooding event much faster and more successfully than a household living paycheck-to-paycheck.”

The Chinese government has allocated more than one trillion yuan ($138bn) – via a special government bond – to support the vulnerable citizens and reconstruction of areas hit by natural disasters in March this year. More than half of the funds are used for “the construction of water conservancy projects like flood control,” reported state media outlet the Global Times.

But the delivery of financial support has been questioned in the past. When Typhoon Doksuri hit China in 2023, only $2bn out of roughly $25bn in aggregate losses were underwritten, according to global reinsurer Munich Re.

In addition, the construction of those sponge cities has already cost China 1.5-1.8bn yuan ($210-250m) between 2015 and 2018. And maintenance will make this bill even larger.

The authors of the Nature paper suggest that the government should work on integrating fragmented “grey infrastructure” – built structures such as drains, pipework and pumping stations – into existing green-blue facilities, but should not rely on engineered infrastructure alone.

Dr Lele Shu, a researcher at the northwest institute of eco-environment and resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, tells the Intellectual magazine that “the [impact of] heavy rain at the current rate cannot be mitigated through traditional engineered approaches alone”.

“Everytime there is heavy rain, the damage it causes will make headlines primarily because there are too many people living in the city,” adds Shu.

The lack of coordination between regional governments and municipalities in flood prone areas also often led to fragmented approaches to disaster management.

In the case of the Yangtze and Pearl deltas, there is a lack of delta-wide plans that “systematically zone land and prioritise investments within one unified hydrological system”, the Nature study adds.

Dr Zheng Yan, a researcher at the Research Institute of Eco-civilisation, China Academy of Social Sciences, noted in the aftermath of the 2023 Beijing flood that government bodies often look after their own jurisdiction and aim only to move the problem and divert the floods quickly, which piled pressure on cities in downstream areas.

Smiley says:

“Floodwaters don’t care about human-created boundaries by municipality, district or province. Effective urban design in one locality may lessen flood risk there, but indirectly increase risk elsewhere. Thinking collectively while centering justice means providing spatially extensive and locally attuned solutions that help all recover effectively instead of exacerbating inequalities.”

What can China learn from other cities?

As flooding is a challenge faced by cities across the world, there is a plethora of ideas and technologies that China can draw on.

The Nature paper suggests that the Yangtze and Pearl deltas, for example, could learn from the Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna delta and the Mekong delta to “improve their responses to regional challenges such as subsidence and erosion, by using and aligning with the underlying dynamics of the deltas that are rapidly changing in response to climate change and anthropogenic activities”.

Building a resilient society that is “proactive and forward-looking, with adequate capabilities to limit detrimental flooding impacts and timely return to the pre-disaster state” is also advocated by the paper.

Rotterdam, a Dutch delta city of 600,000 people that is surrounded by water on four sides, has built water storage facilities, such as an underground parking garage with a basin the size of four Olympic swimming pools. It has also installed green roofs and facades to absorb rainwater.

Japan has built an intricate network of concrete tunnels and vaults about 14 storeys beneath the Saitama prefecture in the outskirts of Tokyo, Japan’s capital city, that can hold more than 1,000 Olympic pools of rainwater.

Both cities’ underground flood diversion facilities are often used as a prime example of a viable flood defence system for urban cities on the frontline of climate change.

Hong Kong has a similar underground stormwater storage system beneath the sport pitches of the Happy Valley Racecourse, designed to withstand once-in-50-years flood events.

However, Chan says it is difficult to compare flood mitigation measures as each city is very different in terms of geography, demographic, densities and topography.

He tells Carbon Brief:

“But in my opinion, China’s megacities should think about using underground spaces to store the sudden extreme discharge from super intensive rainstorms…Tokyo and Rotterdam are quite wise (in that regard) for using their underground spaces.”

The post Q&A: How China is adapting to increasingly frequent flooding appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: How China is adapting to increasingly frequent flooding

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

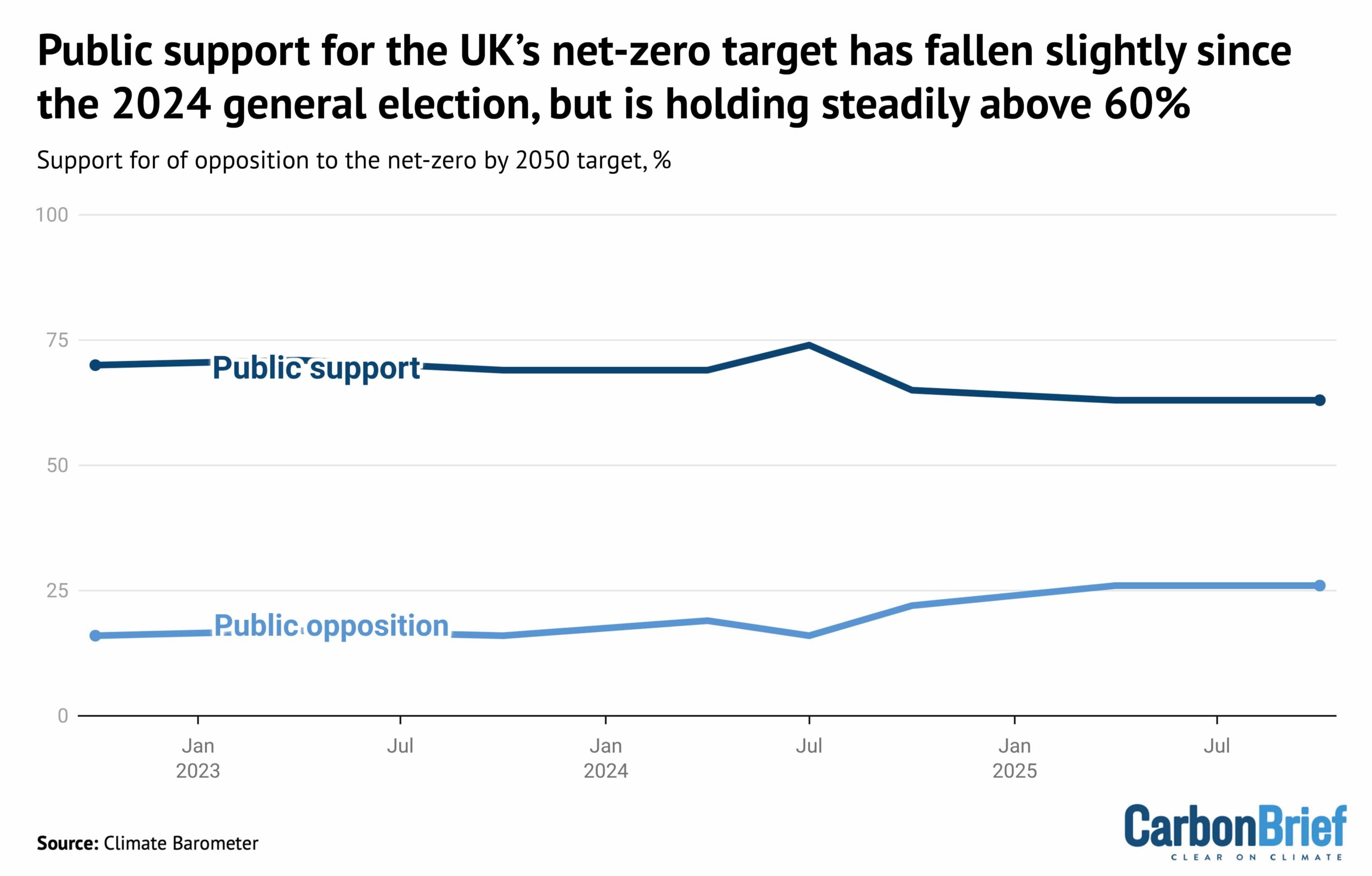

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

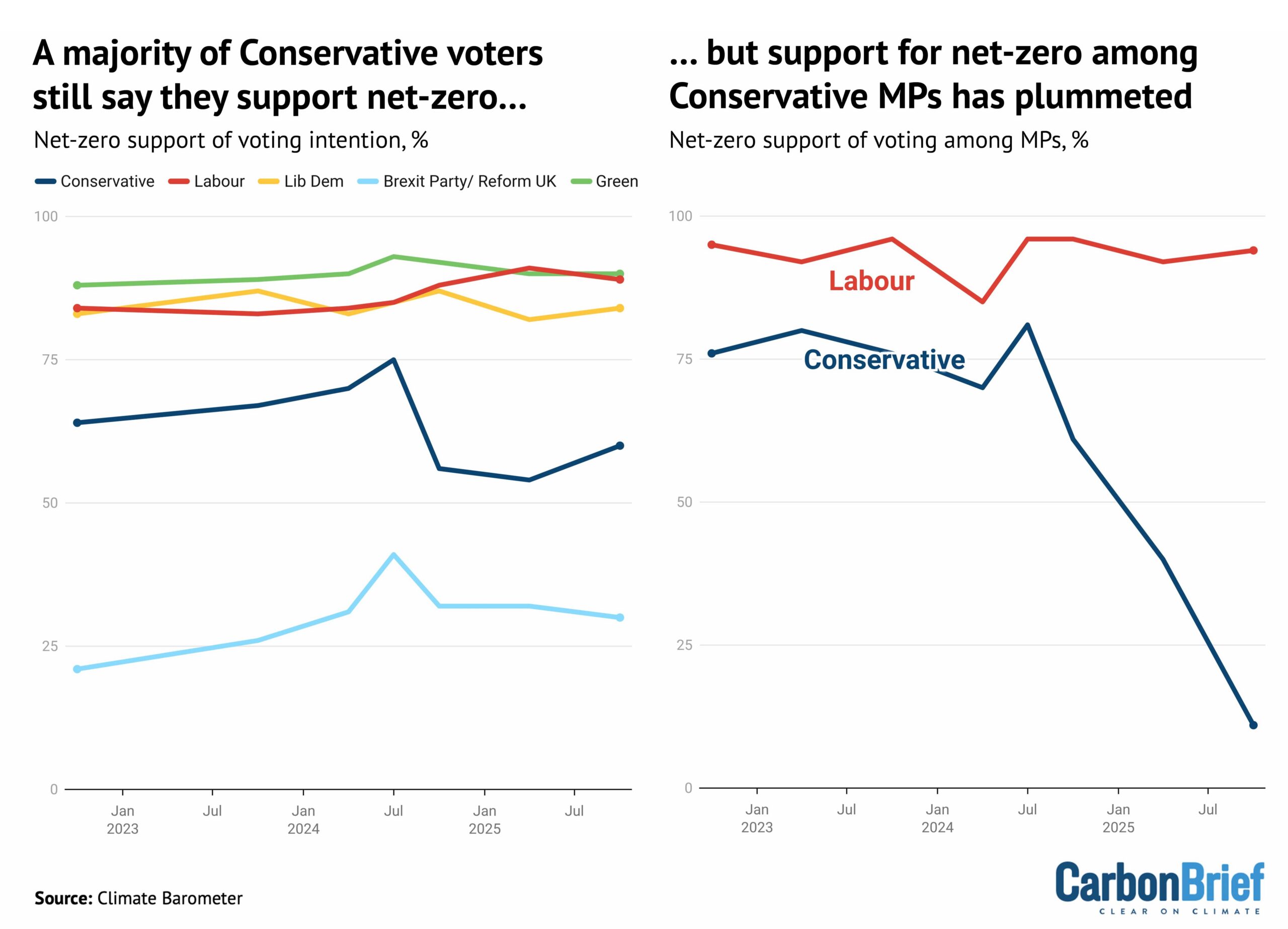

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

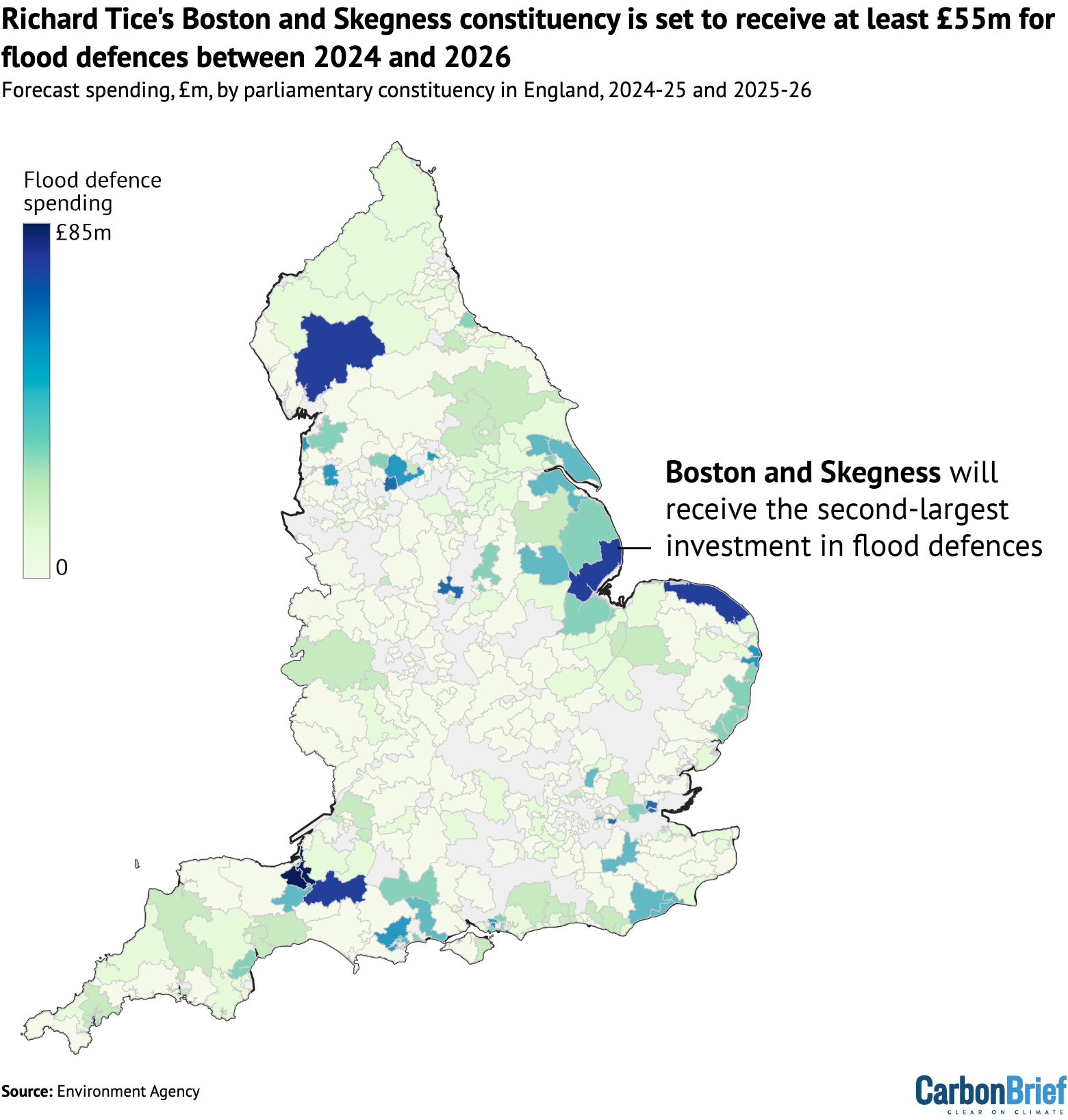

The Lincolnshire constituency held by Richard Tice, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of the hard-right Reform party, has been pledged at least £55m in government funding for flood defences since 2024.

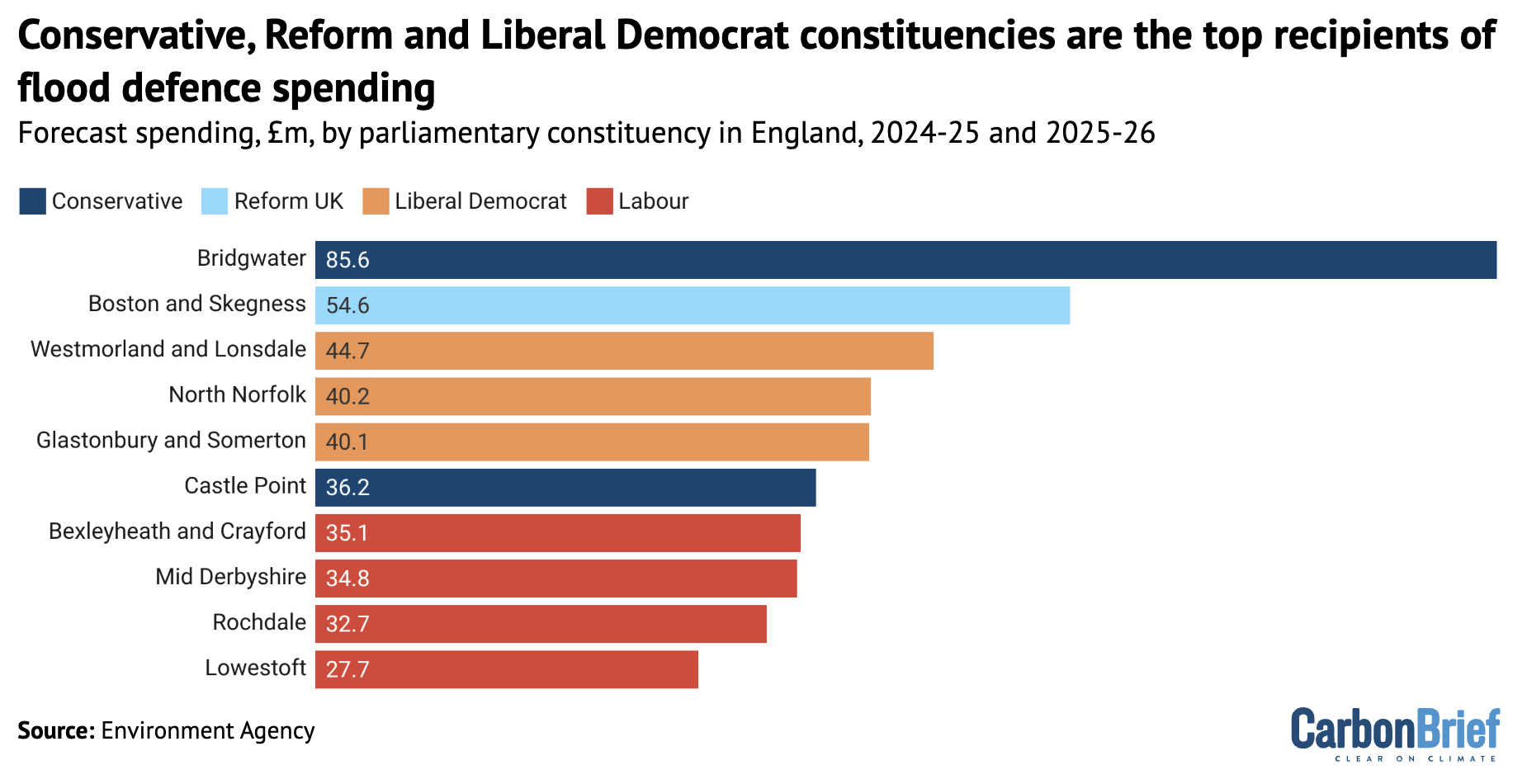

This investment in Boston and Skegness is the second-largest sum for a single constituency from a £1.4bn flood-defence fund for England, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

Flooding is becoming more likely and more extreme in the UK due to climate change.

Yet, for years, governments have failed to spend enough on flood defences to protect people, properties and infrastructure.

The £1.4bn fund is part of the current Labour government’s wider pledge to invest a “record” £7.9bn over a decade on protecting hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses from flooding.

As MP for one of England’s most flood-prone regions, Tice has called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

He is also one of Reform’s most vocal opponents of climate action and what he calls “net stupid zero”. He denies the scientific consensus on climate change and has claimed, falsely and without evidence, that scientists are “lying”.

Flood defences

Last year, the government said it would invest £2.65bn on flood and coastal erosion risk management (FCERM) schemes in England between April 2024 and March 2026.

This money was intended to protect 66,500 properties from flooding. It is part of a decade-long Labour government plan to spend more than £7.9bn on flood defences.

There has been a consistent shortfall in maintaining England’s flood defences, with the Environment Agency expecting to protect fewer properties by 2027 than it had initially planned.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) has attributed this to rising costs, backlogs from previous governments and a lack of capacity. It also points to the strain from “more frequent and severe” weather events, such as storms in recent years that have been amplified by climate change.

However, the CCC also said last year that, if the 2024-26 spending programme is delivered, it would be “slightly closer to the track” of the Environment Agency targets out to 2027.

The government has released constituency-level data on which schemes in England it plans to fund, covering £1.4bn of the 2024-26 investment. The other half of the FCERM spending covers additional measures, from repairing existing defences to advising local authorities.

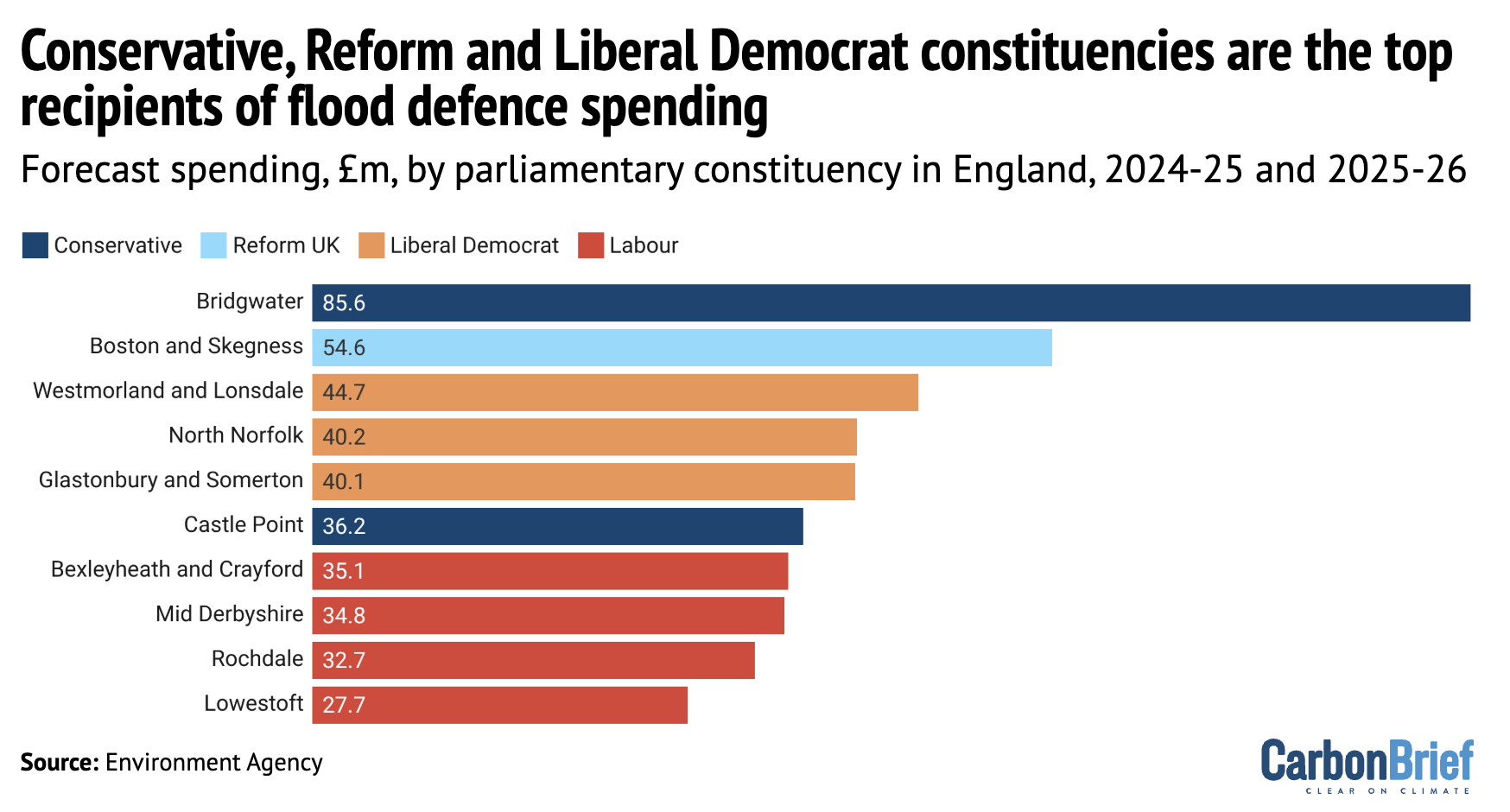

The map below shows the distribution of spending on FCERM schemes in England over the past two years, highlighting the constituency of Richard Tice.

By far the largest sum of money – £85.6m in total – has been committed to a tidal barrier and various other defences in the Somerset constituency of Bridgwater, the seat of Conservative MP Ashley Fox.

Over the first months of 2026, the south-west region has faced significant flooding and Fox has called for more support from the government, citing “climate patterns shifting and rainfall intensifying”.

He has also backed his party’s position that “the 2050 net-zero target is impossible” and called for more fossil-fuel extraction in the North Sea.

Tice’s east-coast constituency of Boston and Skegness, which is highly vulnerable to flooding from both rivers and the sea, is set to receive £55m. Among the supported projects are beach defences from Saltfleet to Gibraltar Point and upgrades to pumping stations.

Overall, Boston and Skegness has the second-largest portion of flood-defence funding, as the chart below shows. Constituencies with Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs occupied the other top positions.

Overall, despite Labour MPs occupying 347 out of England’s 543 constituencies – nearly two-thirds of the total – more than half of the flood-defence funding was distributed to constituencies with non-Labour MPs. This reflects the flood risk in coastal and rural areas that are not traditional Labour strongholds.

Reform funding

While Reform has just eight MPs, representing 1% of the population, its constituencies have been assigned 4% of the flood-defence funding for England.

Nearly all of this money was for Tice’s constituency, although party leader Nigel Farage’s coastal Clacton seat in Kent received £2m.

Reform UK is committed to “scrapping net-zero” and its leadership has expressed firmly climate-sceptic views.

Much has been made of the disconnect between the party’s climate policies and the threat climate change poses to its voters. Various analyses have shown the flood risk in Reform-dominated areas, particularly Lincolnshire.

Tice has rejected climate science, advocated for fossil-fuel production and criticised Environment Agency flood-defence activities. Yet, he has also called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

This may reflect Tice’s broader approach to climate change. In a 2024 interview with LBC, he said:

“Where you’ve got concerns about sea level defences and sea level rise, guess what? A bit of steel, a bit of cement, some aggregate…and you build some concrete sea level defences. That’s how you deal with rising sea levels.”

While climate adaptation is viewed as vital in a warming world, there are limits on how much societies can adapt and adaptation costs will continue to increase as emissions rise.

The post Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

Greenhouse Gases

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Food inflation on the rise

DELUGE STRIKES FOOD: Extreme rainfall and flooding across the Mediterranean and north Africa has “battered the winter growing regions that feed Europe…threatening food price rises”, reported the Financial Times. Western France has “endured more than 36 days of continuous rain”, while farmers’ associations in Spain’s Andalusia estimate that “20% of all production has been lost”, it added. Policy expert David Barmes told the paper that the “latest storms were part of a wider pattern of climate shocks feeding into food price inflation”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

NO BEEF: The UK’s beef farmers, meanwhile, “face a double blow” from climate change as “relentless rain forces them to keep cows indoors”, while last summer’s drought hit hay supplies, said another Financial Times article. At the same time, indoor growers in south England described a 60% increase in electricity standing charges as a “ticking timebomb” that could “force them to raise their prices or stop production, which will further fuel food price inflation”, wrote the Guardian.

‘TINDERBOX’ AND TARIFFS: A study, covered by the Guardian, warned that major extreme weather and other “shocks” could “spark social unrest and even food riots in the UK”. Experts cited “chronic” vulnerabilities, including climate change, low incomes, poor farming policy and “fragile” supply chains that have made the UK’s food system a “tinderbox”. A New York Times explainer noted that while trade could once guard against food supply shocks, barriers such as tariffs and export controls – which are being “increasingly” used by politicians – “can shut off that safety valve”.

El Niño looms

NEW ENSO INDEX: Researchers have developed a new index for calculating El Niño, the large-scale climate pattern that influences global weather and causes “billions in damages by bringing floods to some regions and drought to others”, reported CNN. It added that climate change is making it more difficult for scientists to observe El Niño patterns by warming up the entire ocean. The outlet said that with the new metric, “scientists can now see it earlier and our long-range weather forecasts will be improved for it.”

WARMING WARNING: Meanwhile, the US Climate Prediction Center announced that there is a 60% chance of the current La Niña conditions shifting towards a neutral state over the next few months, with an El Niño likely to follow in late spring, according to Reuters. The Vibes, a Malaysian news outlet, quoted a climate scientist saying: “If the El Niño does materialise, it could possibly push 2026 or 2027 as the warmest year on record, replacing 2024.”

CROP IMPACTS: Reuters noted that neutral conditions lead to “more stable weather and potentially better crop yields”. However, the newswire added, an El Niño state would mean “worsening drought conditions and issues for the next growing season” to Australia. El Niño also “typically brings a poor south-west monsoon to India, including droughts”, reported the Hindu’s Business Line. A 2024 guest post for Carbon Brief explained that El Niño is linked to crop failure in south-eastern Africa and south-east Asia.

News and views

- DAM-AG-ES: Several South Korean farmers filed a lawsuit against the country’s state-owned utility company, “seek[ing] financial compensation for climate-related agricultural damages”, reported United Press International. Meanwhile, a national climate change assessment for the Philippines found that the country “lost up to $219bn in agricultural damages from typhoons, floods and droughts” over 2000-10, according to Eco-Business.

- SCORCHED GRASS: South Africa’s Western Cape province is experiencing “one of the worst droughts in living memory”, which is “scorching grass and killing livestock”, said Reuters. The newswire wrote: “In 2015, a drought almost dried up the taps in the city; farmers say this one has been even more brutal than a decade ago.”

- NOUVELLE VEG: New guidelines published under France’s national food, nutrition and climate strategy “urged” citizens to “limit” their meat consumption, reported Euronews. The delayed strategy comes a month after the US government “upended decades of recommendations by touting consumption of red meat and full-fat dairy”, it noted.

- COURTING DISASTER: India’s top green court accepted the findings of a committee that “found no flaws” in greenlighting the Great Nicobar project that “will lead to the felling of a million trees” and translocating corals, reported Mongabay. The court found “no good ground to interfere”, despite “threats to a globally unique biodiversity hotspot” and Indigenous tribes at risk of displacement by the project, wrote Frontline.

- FISH FALLING: A new study found that fish biomass is “falling by 7.2% from as little as 0.1C of warming per decade”, noted the Guardian. While experts also pointed to the role of overfishing in marine life loss, marine ecologist and study lead author Dr Shahar Chaikin told the outlet: “Our research proves exactly what that biological cost [of warming] looks like underwater.”

- TOO HOT FOR COFFEE: According to new analysis by Climate Central, countries where coffee beans are grown “are becoming too hot to cultivate them”, reported the Guardian. The world’s top five coffee-growing countries faced “57 additional days of coffee-harming heat” annually because of climate change, it added.

Spotlight

Nature talks inch forward

This week, Carbon Brief covers the latest round of negotiations under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which occurred in Rome over 16-19 February.

The penultimate set of biodiversity negotiations before October’s Conference of the Parties ended in Rome last week, leaving plenty of unfinished business.

The CBD’s subsidiary body on implementation (SBI) met in the Italian capital for four days to discuss a range of issues, including biodiversity finance and reviewing progress towards the nature targets agreed under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

However, many of the major sticking points – particularly around finance – will have to wait until later this summer, leaving some observers worried about the capacity for delegates to get through a packed agenda at COP17.

The SBI, along with the subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) will both meet in Nairobi, Kenya, later this summer for a final round of talks before COP17 kicks off in Yerevan, Armenia, on 19 October.

Money talks

Finance for nature has long been a sticking point at negotiations under the CBD.

Discussions on a new fund for biodiversity derailed biodiversity talks in Cali, Colombia, in autumn 2024, requiring resumed talks a few months later.

Despite this, finance was barely on the agenda at the SBI meetings in Rome. Delegates discussed three studies on the relationship between debt sustainability and implementation of nature plans, but the more substantive talks are set to take place at the next SBI meeting in Nairobi.

Several parties “highlighted concerns with the imbalance of work” on finance between these SBI talks and the next ones, reported Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Lim Li Ching, senior researcher at Third World Network, noted that tensions around finance permeated every aspect of the talks. She told Carbon Brief:

“If you’re talking about the gender plan of action – if there’s little or no financial resources provided to actually put it into practice and implement it, then it’s [just] paper, right? Same with the reporting requirements and obligations.”

Monitoring and reporting

Closely linked to the issue of finance is the obligations of parties to report on their progress towards the goals and targets of the GBF.

Parties do so through the submission of national reports.

Several parties at the talks pointed to a lack of timely funding for driving delays in their reporting, according to ENB.

A note released by the CBD Secretariat in December said that no parties had submitted their national reports yet; by the time of the SBI meetings, only the EU had. It further noted that just 58 parties had submitted their national biodiversity plans, which were initially meant to be published by COP16, in October 2024.

Linda Krueger, director of biodiversity and infrastructure policy at the environmental not-for-profit Nature Conservancy, told Carbon Brief that despite the sparse submissions, parties are “very focused on the national report preparation”. She added:

“Everybody wants to be able to show that we’re on the path and that there still is a pathway to getting to 2030 that’s positive and largely in the right direction.”

Watch, read, listen

NET LOSS: Nigeria’s marine life is being “threatened” by “ghost gear” – nets and other fishing equipment discarded in the ocean – said Dialogue Earth.

COMEBACK CAUSALITY: A Vox long-read looked at whether Costa Rica’s “payments for ecosystem services” programme helped the country turn a corner on deforestation.

HOMEGROWN GOALS: A Straits Times podcast discussed whether import-dependent Singapore can afford to shelve its goal to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030.

‘RUSTING’ RIVERS: The Financial Times took a closer look at a “strange new force blighting the [Arctic] landscape”: rivers turning rust-orange due to global warming.

New science

- Lakes in the Congo Basin’s peatlands are releasing carbon that is thousands of years old | Nature Geoscience

- Natural non-forest ecosystems – such as grasslands and marshlands – were converted for agriculture at four times the rate of land with tree cover between 2005 and 2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Around one-quarter of global tree-cover loss over 2001-22 was driven by cropland expansion, pastures and forest plantations for commodity production | Nature Food

In the diary

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean | Brasília

- 5 March: Nepal general elections

- 9-20 March: First part of the thirty-first session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) | Kingston, Jamaica

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits