China’s central and local governments, as well as state-owned enterprises, are busy preparing for the next five-year planning period, spanning 2026-30.

The top-level 15th five-year plan, due to be published in March 2026, will shape greenhouse gas emissions in China – and globally – for the rest of this decade and beyond.

The targets set under the plan will determine whether China is able to get back on track for its 2030 climate commitments, which were made personally by President Xi Jinping in 2021.

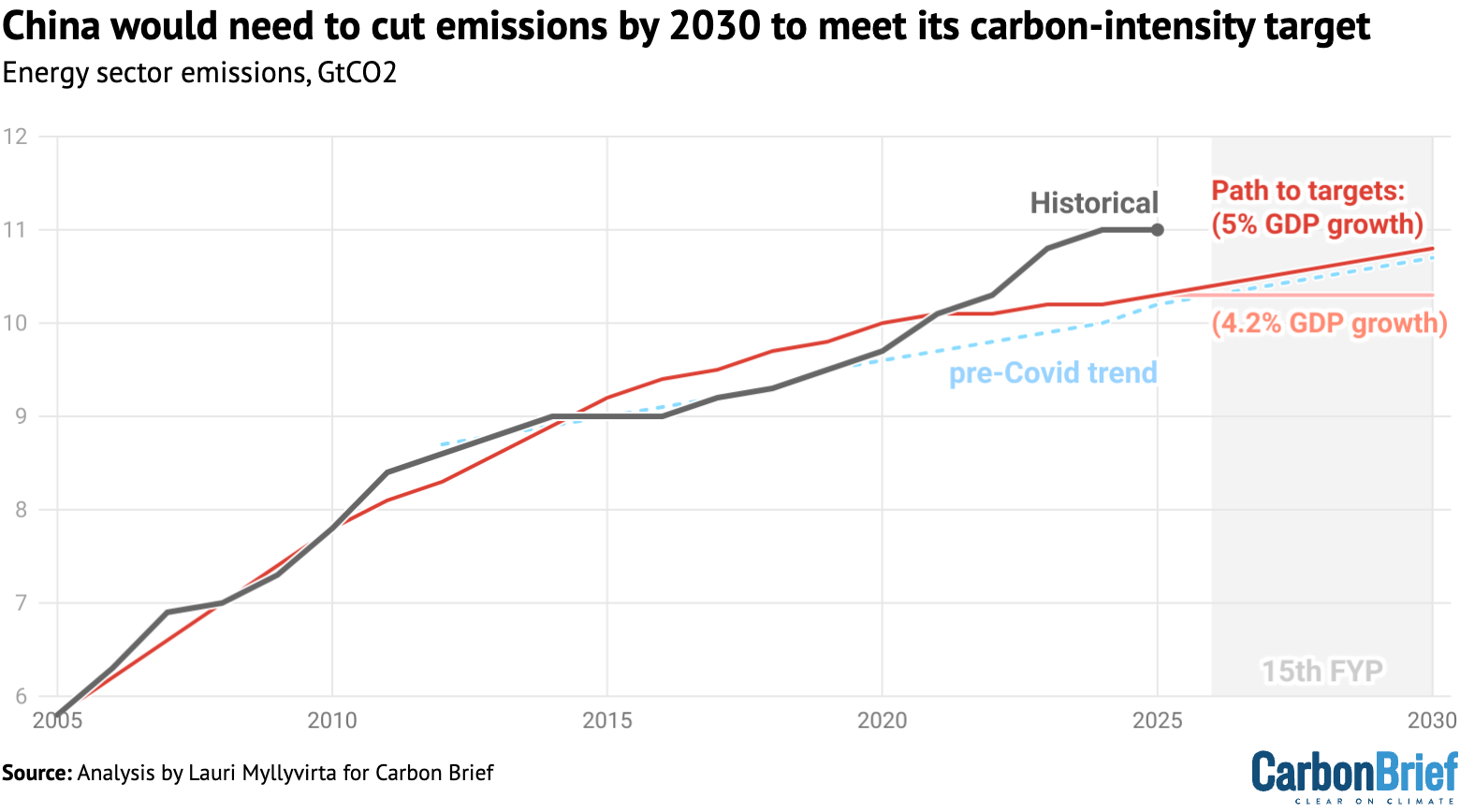

This would require energy sector carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions to fall by 2-6% by 2030, much more than implied by the 2035 target of a 7-10% cut from “peak levels”.

The next five-year plan will set the timing and the level of this emissions peak, as well as whether emissions will be allowed to rebound in the short term.

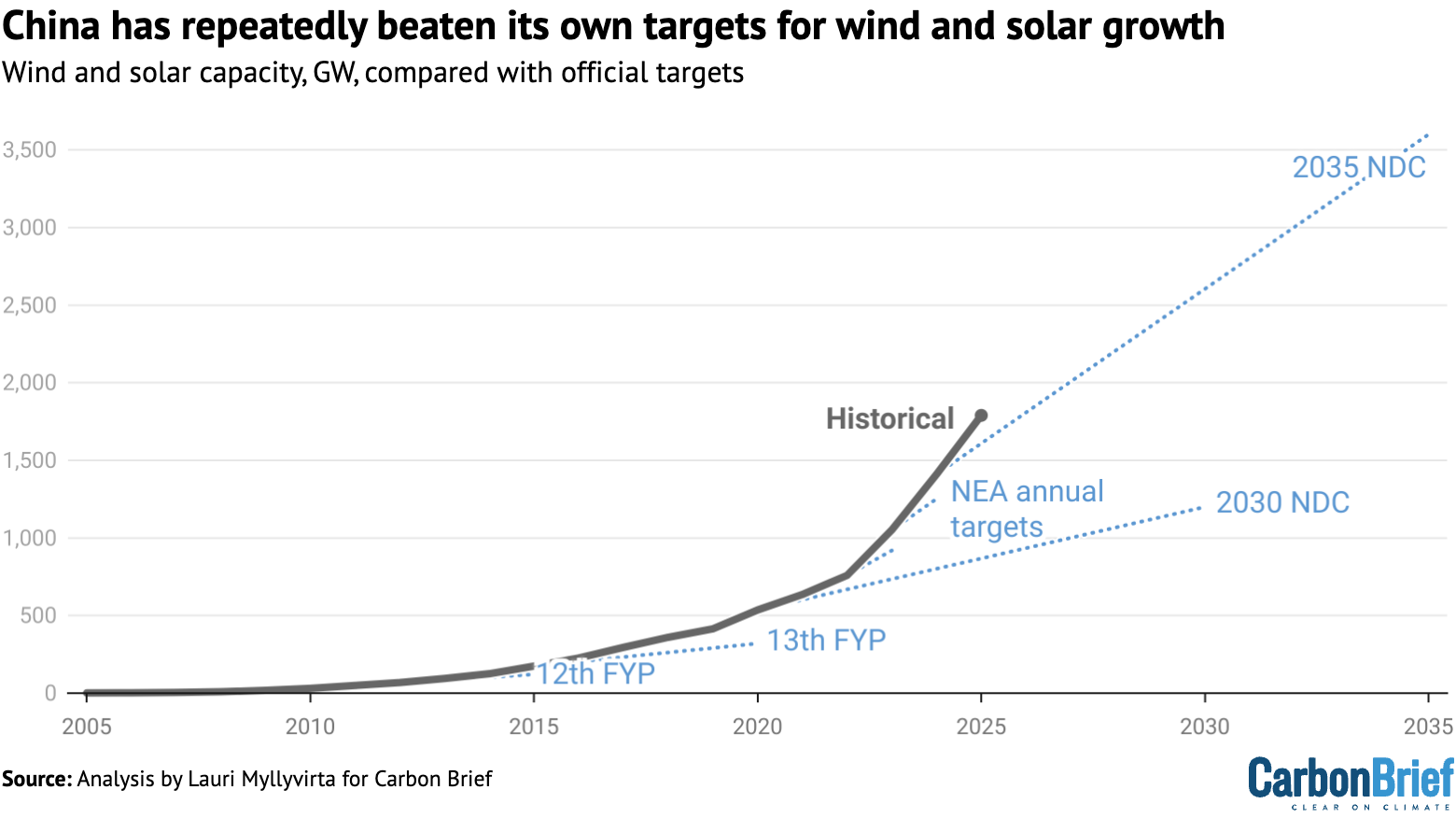

The plan will also affect the pace of clean-energy growth, which has repeatedly beaten previous targets and has become a key driver of the nation’s economy.

Some 250-350 gigawatts (GW) of new wind and solar would be needed each year to meet China’s 2030 commitments, far above the 200GW being targeted.

Finally, the plans will shape China’s transition away from fossil fuels, with key sectors now openly discussing peak years for coal and oil demand, but with 330GW of new coal capacity in the works and more than 500 new chemical industry projects due in the next five years.

These issues come together in five key questions for climate and energy that Chinese policymakers will need to answer in the final five-year plan documents next year.

Five-year plans and their role in China

1. Will the plan put China back on track for its 2030 Paris pledge?

2. Will the plan upgrade clean-energy targets or pave the way to exceed them?

3. Will the plan set an absolute cap on coal consumption?

4. Will ‘dual control’ of carbon prevent an emission rebound?

5. Will it limit coal-power and chemical-industry growth?

Five-year plans and their role in China

Five-year plans are an essential part of China’s policymaking, guiding decision-making at government bodies, enterprises and banks. The upcoming 15th five-year plan will cover the years 2026-30, set targets for 2030 and use 2025 as its base year.

The top-level five-year plan will be published in March 2026 and is known as the five-year plan on economic and social development. This overarching document will be followed by dozens of sectoral plans, as well as province- and company-level plans.

The sectoral plans are usually published in the second year of the five-year period, meaning they would be expected in 2027.

There will be five-year plans for the energy sector, the electricity sector, for renewable energy, nuclear, coal and many other sub-sectors, as well as plans for major industrial sectors such as steel, construction materials and chemicals.

It is likely that there will also be a plan for carbon emissions or carbon peaking and a five-year plan for the environment.

During the previous five-year period, the plans of provinces and state-owned enterprises for very large-scale solar and wind projects were particularly important, far exceeding the central government’s targets.

The five-year plans create incentives for provincial governments and ministries by setting quantified targets that they are responsible for meeting. These targets influence the performance evaluations of governors, CEOs and party secretaries.

The plans also designate favoured sectors and projects, directing bank lending, easing permitting and providing an implicit government guarantee for the project developers.

Each plan lists numerous things that should be “promoted”, banned or controlled, leaving the precise implementation to different state organs and state-owned enterprises.

Five-year plans can introduce and coordinate national mega-projects, such as the gigantic clean-energy “bases” and associated electricity transmission infrastructure, which were outlined in the previous five-year plan in 2021.

The plans also function as a policy roadmap, assigning the tasks to develop new policies and providing stakeholders with visibility to expected policy developments.

1. Will the plan put China back on track for its 2030 Paris pledge?

Reducing carbon intensity – the energy-sector carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions per unit of GDP – has been the cornerstone of China’s climate commitments since the 2020 target announced at the 2009 Copenhagen climate conference.

Consequently, the last three five-year plans have included a carbon-intensity target. The next 15th one is highly likely to set a carbon-intensity target too, given that this is the centerpiece of China’s 2030 climate targets.

Moreover, it was president Xi himself who pledged in 2021 that China would reduce its carbon intensity to 65% below 2005 levels by 2030. This was later formalised in China’s 2030 “nationally determined contribution” (NDC) under the Paris Agreement.

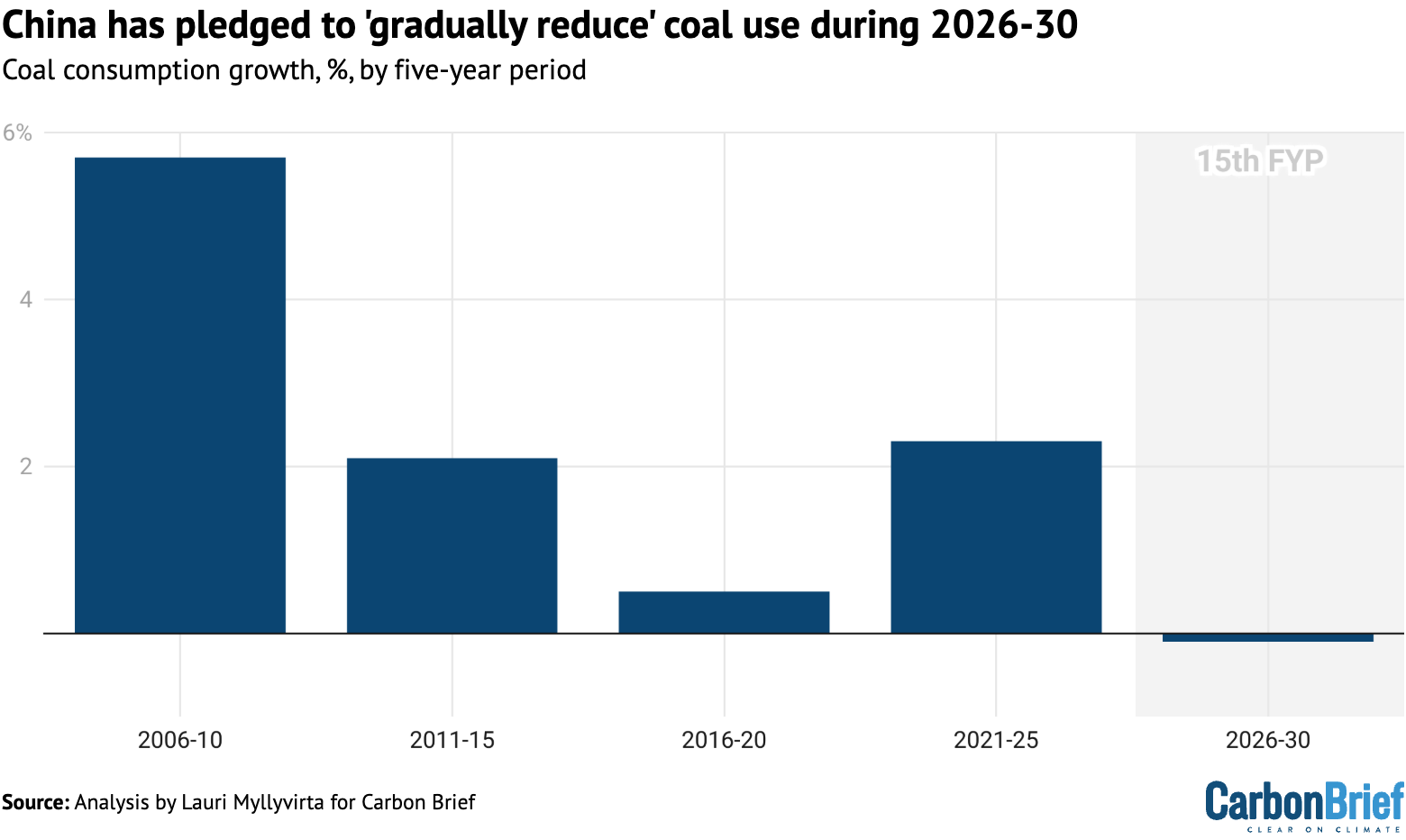

Xi also pledged that China would gradually reduce coal consumption during the five-year period up to 2030. However, China is significantly off track to these targets.

China’s CO2 emissions grew more quickly in the early 2020s than they had been before the Coronavirus pandemic, as shown in the figure below. This stems from a surge in energy consumption during and after the “zero-Covid” period, together with a rapid expansion of coal-fired power and the fossil-fuel based chemical industry. as shown in the figure below.

As a result, meeting the 2030 intensity target would require a reduction in CO2 emissions from current levels, with the level of the drop depending on the rate of economic growth.

Xi’s personal imprimatur would make missing these 2030 targets awkward for China, particularly given the country’s carefully cultivated reputation for delivery. On the other hand, meeting them would require much stronger action than initially anticipated.

Recent policy documents and statements, in particular the recommendations of the Central Committee of the Communist Party for the next five-year plan, and the government’s work report for 2025, have put the emphasis on China’s target to peak emissions before 2030 and the new 2035 emission target, which would still allow emissions to increase over the next five-year period. The earlier 2030 commitments risk being buried as inconvenient.

Still, the State Council’s plan for controlling carbon emissions, published in 2024, says that carbon intensity will be a “binding indicator” for the next five-year period, meaning that a target will be included in the top-level plan published in March 2026.

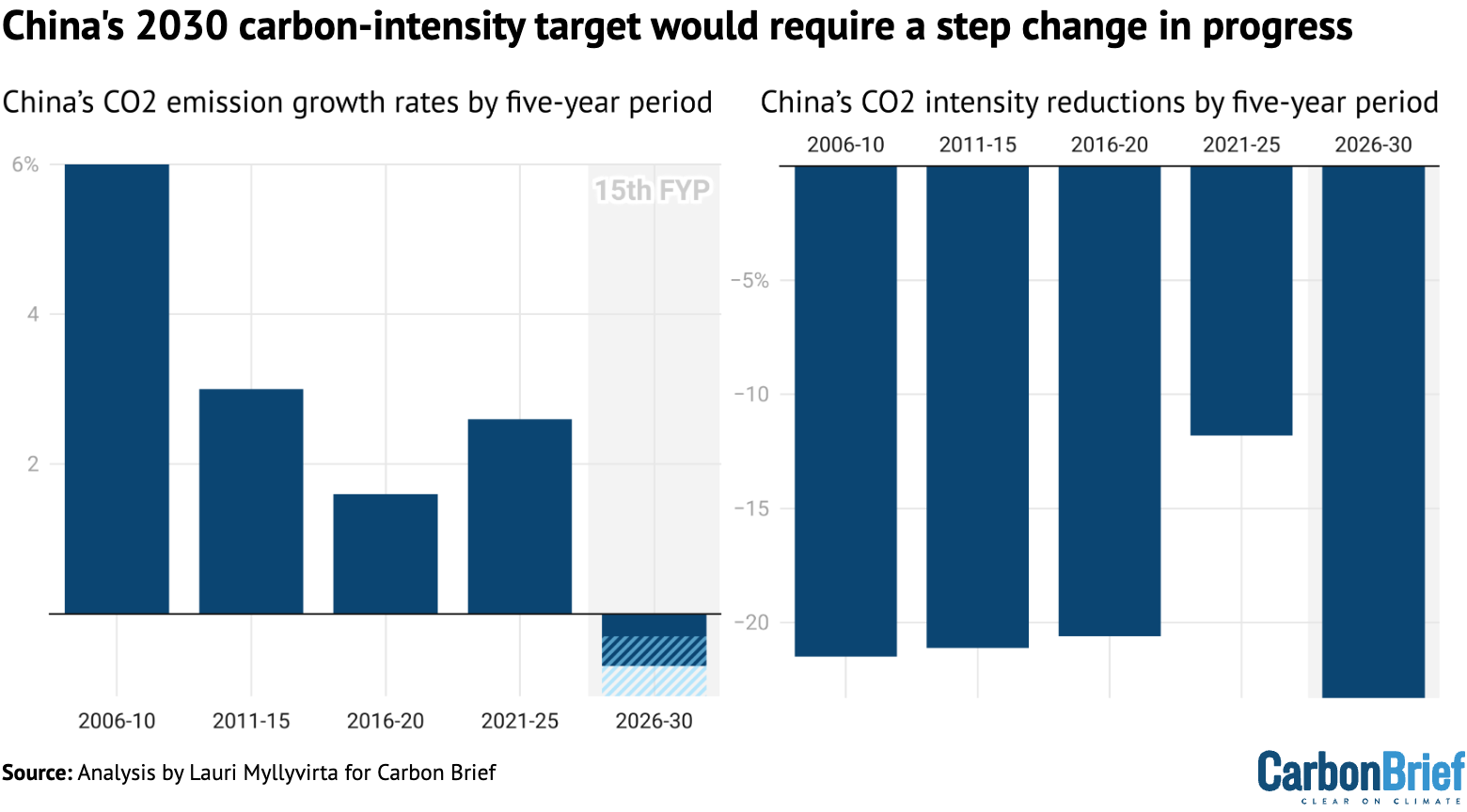

China is only set to achieve a reduction of about 12% in carbon intensity from 2020 to 2025 – a marked slowdown relative to previous periods, as shown in the figure below.

(This is based on reductions reported annually by the National Bureau of Statistics until 2024 and a projected small increase in energy-sector CO2 emissions in 2025. Total CO2 emissions could still fall this year, when the fall in process emissions from cement production is factored in.)

A 12% fall would be far less than the 18% reduction targeted under the 14th five-year plan, as well as falling short of what would be needed to stay on track to the 2030 target.

To make up the shortfall and meet the 2030 intensity target, China would need to set a goal of around 23% in the next five-year plan. As such, this target will be a key test of China’s determination to honour its climate commitments.

A carbon-intensity target of 23% is likely to receive pushback from some policymakers, as it is much higher than achieved in previous periods. No government or thinktank documents have yet been published with estimates of what the 2030 intensity target would need to be.

In practice, meeting the 2030 carbon intensity target would require reducing CO2 emissions by 2-6% in absolute terms from 2025, assuming a GDP growth rate of 4.2-5.0%.

China needs 4.2% GDP growth over the next decade to achieve Xi’s target of doubling the country’s GDP per capita from 2020 to 2035, a key part of his vision of achieving “socialist modernisation” by 2035, with the target for the next five years likely to be set higher.

Recent high-level policy documents have avoided even mentioning the 2030 intensity target. It is omitted in recommendations of the Central Committee of the Communist Party for the next five-year plan, the foundation on which the plan will be formulated.

Instead, the recommendations emphasised “achieving the carbon peak as scheduled” and “promoting the peaking of coal and oil consumption”, which are less demanding.

The environment ministry, in contrast, continues to pledge efforts to meet the carbon intensity target. However, they are not the ones writing the top-level five-year plan.

The failure to meet the 2025 intensity target has been scarcely mentioned in top-level policy discussions. There was no discernible effort to close the gap to the target, even after the midway review of the five-year plan recognised the shortfall.

The State Council published an action plan to get back on track, including a target for reducing carbon intensity in 2024 – albeit one not sufficient to close the shortfall. Yet this plan, in turn, was not followed up with an annual target for 2025.

The government could also devise ways to narrow the gap to the target on paper, through statistical revisions or tweaks to the definition of carbon intensity, as the term has not been defined in China’s NDCs.

Notably, unlike China’s previous NDC, its latest pledge did not include a progress update for carbon intensity. The latest official update sent to the UN only covers the years to 2020.

This leaves some more leeway for revisions, even though China’s domestic “statistical communiques”, published every year, have included official numbers up to 2024.

Coal consumption growth around 2022 was likely over-reported, so statistical revisions could reduce reported emissions and narrow the gap to the target. Including process emissions from cement, which have been falling rapidly in recent years, and changing how emissions from fossil fuels used as raw materials in the chemicals industry are accounted for, so-called non-energy use, which has been growing rapidly, could make the target easier to meet.

2. Will the plan upgrade clean-energy targets or pave the way to exceed them?

The need to accelerate carbon-intensity reductions also has implications for clean-energy targets.

The current goal is for non-fossil fuels to make up 25% of energy supplies in 2030, up from the 21% expected to be reached this year.

This expansion would be sufficient to achieve the reduction in carbon intensity needed in the next five years, but only if energy consumption growth slows down very sharply. Growth would need to slow to around 1% per year, from 4.1% in the past five years 2019-2024 and from 3.7% in the first three quarters of 2025.

The emphasis on manufacturing in the Central Committee’s recommendations for the next five-year plan is hard to reconcile with such a sharp slowdown, even if electrification will help reduce primary energy demand. During the current five-year period, China abolished the system of controlling total energy consumption and energy intensity, removing the incentive for local governments to curtail energy-intensive projects and industries.

Even if the ratio of total energy demand growth to GDP growth returned to pre-Covid levels, implying total energy demand growth of 2.5% per year, then the share of non-fossil energy would need to reach 31% by 2030 to deliver the required reduction in carbon intensity.

However, China recently set the target for non-fossil energy in 2035 at just 30%. This risks cementing a level of ambition that is likely too low to enable the 2030 carbon-intensity target to be met, whereas meeting it would require non-fossil energy to reach 30% by 2030.

There is ample scope for China to beat its targets for non-fossil energy.

However, given that the construction of new nuclear and hydropower plants generally takes five years or more in China, only those that are already underway have the chance to be completed by 2030. This leaves wind and solar as the quick-to-deploy power generation options that can deliver more non-fossil energy during this five-year period.

Reaching a much higher share of non-fossil energy in 2030, in turn, would therefore require much faster growth in solar and wind than currently targeted. Both the NDRC power-sector plan for 2025-27 and China’s new NDC aim for the addition of about 200 gigawatts (GW) per year of solar and wind capacity, much lower than the 360GW achieved in 2024.

If China continued to add capacity at similar rates, going beyond the government’s targets and instead installing 250-350GW of new solar and wind in each of the next five years, then this would be sufficient to meet the 2030 intensity target, assuming energy demand rising by 2.5-3.0% per year.

All previous wind and solar targets have been exceeded by a wide margin, as shown in the figure below, so there is a good chance that the current one will be, too.

While the new pricing policy for wind and solar has created a much more uncertain and less supportive policy environment for the development of clean energy, provinces have substantial power to create a more supportive environment.

For example, they can include clean-energy projects and downstream projects using clean electricity and green hydrogen in their five-year plans, as well as developing their local electricity markets in a direction that enables new solar and wind projects.

3. Will the plan set an absolute cap on coal consumption?

In 2020, Xi pledged that China would “gradually reduce coal consumption” during the 2026-30 period. The commitment is somewhat ambiguous.

It could be interpreted as requiring a reduction starting in 2026, or a reduction below 2025 levels by 2030, which in practice would mean coal consumption peaking around the midway point of the five-year period, in other words 2027-28.

In either case, if Xi’s pledge were to be cemented in the 15th five-year plan then it would need to include an absolute reduction in coal consumption during 2026-30. An illustration of what this might look like is shown in the figure below.

However, the commitment to reduce coal consumption was missing from China’s new NDC for 2035 and from the Central Committee’s recommendations for the next five-year plan.

The Central Committee called for “promoting a peak in coal and oil consumption”, which is a looser goal as it could still allow an increase in consumption during the period, if the growth in the first years towards 2030 exceeds the reduction after the peak.

The difference between “peaking” and “reducing” is even larger because China has not defined what “peaking” means, even though peaking carbon emissions is the central goal of China’s climate policy for this decade.

Peaking could be defined as achieving a certain reduction from peak before the deadline, or having policies in place that constrain emissions or coal use. It could be seen as reaching a plateau or as an absolute reduction.

While the commitment to “gradually reduce” coal consumption has seemed to fade from discussion, there have been several publications discussing the peak years for different fossil fuels, which could pave the way for more specific peaking targets.

State news agency Xinhua published an article – only in English – saying that coal consumption would peak around 2027 and oil consumption around 2026, while also mentioning the pledge to reduce coal consumption.

The energy research arm of the National Development and Reform Council had said earlier that coal and oil consumption would peak halfway through the next five-year period, in other words 2027-28, while the China Coal Association advocated a slightly later target of 2028.

Setting a targeted peak year for coal consumption before the half-way point of the five-year period could be a way to implement the coal reduction commitment.

With the fall in oil use in transportation driven by EVs, railways and other low-carbon transportation, oil consumption is expected to peak soon or to have peaked already.

State-owned oil firm CNPC projects that China’s oil consumption will peak in 2025 at 770m tonnes, while Sinopec thinks that continued demand for petrochemical feedstocks will keep oil consumption growing until 2027 and it will then peak at 790-800m tonnes.

4. Will ‘dual control’ of carbon prevent an emission rebound?

With the focus on realising a peak in emissions before 2030, there could be a strong incentive for provincial governments and industries to increase emissions in the early years of the five-year period to lock in a higher level of baseline emissions.

This approach is known as “storming the peak” (碳冲锋) in Chinese and there have been warnings about it ever since Xi announced the current CO2 peaking target in 2020.

Yet, the emphasis on peaking has only increased, with the recent announcement on promoting peaks in coal consumption and oil consumption, as well as the 2035 emission-reduction target being based on “peak levels”.

The policy answer to this is creating a system to control carbon intensity and total CO2 emissions – known as “dual control of carbon” – building on the earlier system for the “dual control of energy” consumption.

Both the State Council and the Central Committee have set the aim of operationalising the “dual control of carbon” system in the 15th five-year plan period.

However, policy documents speak of building the carbon dual-control system during the five-year period rather than it becoming operational at the start of the period.

For example, an authoritative analysis of the Central Committee’s recommendations by China Daily says that “solid progress” is needed in five areas to actually establish the system, including assessment of carbon targets for local governments as well as carbon management for industries and enterprises.

The government set an annual target for reducing carbon intensity for the first time in 2024, but did not set one for 2025, also signaling that there was no preparedness to begin controlling carbon intensity, let alone total carbon emissions, yet.

If the system is not in place at the start of the five-year period, with firm targets, there could be an opportunity for local governments to push for early increases in emissions – and potentially even an incentive for such emission increases, if they expect strict control later.

Another question is how the “dual” element of controlling both carbon intensity and absolute CO2 emissions is realised. While carbon intensity is meant to be the main focus during the next five years, with the priority shifting to reducing absolute emissions after the peak, having the “dual control” in place requires some kind of absolute cap on CO2 emissions.

The State Council has said that China will begin introducing “absolute emissions caps in some industries for the first time” from 2027 under its national carbon market. It is possible that the control of absolute carbon emissions will only apply to these sectors.

The State Council also said that the market would cover all “major emitting sectors” by 2027, but absolute caps would only apply to sectors where emissions have “stabilised”.

5. Will it limit coal-power and chemical-industry growth?

During the current five-year period, China’s leadership went from pledging to “strictly control” new coal-fired power projects to actively promoting them.

If clean-energy growth continues at the rates achieved in recent years, there will be no more space for coal- and gas-fired power generation to expand, even if new capacity is built. Stable or falling demand for power generation from fossil fuels would mean a sharp decline in the number of hours each plant is able to run, eroding its economic viability.

Showing the scale of the planned expansion, researchers from China Energy Investment Corporation, the second-largest coal-power plant operator in China, project that China’s coal-fired power capacity could expand by 300GW from the end of 2024 to 2030 and then plateau at that level for a decade. The projection relies on continued growth of power generation from coal until 2030 and a very slow decline thereafter.

The completion of the 325GW projects already under construction and permitted at the end of 2024, as well as an additional 42GW permitted in the first three quarters of 2025, could in fact lead to a significantly larger increase, if the retirement of existing capacity remains slow.

In effect, China’s policymakers face a choice between slowing down the clean-energy boom, which has been a major driver of economic growth in recent years, upsetting coal project developers, who expect to operate their coal-fired power plants at a high utilisation, or retiring older coal-power plants en masse.

Their response to these choices may not become clear for some time. The top-level five-year plan that will be published in March 2026 will likely provide general guidelines, but the details of capacity development will be relegated to the sectoral plans for energy.

The other sector where fossil fuel-based capacity is rapidly increasing is the chemical industry, both oil and coal-based. In this sector, capacity growth has led directly to increases in output, making the sector the only major driver of emissions increases after early 2024.

The expansion is bound to continue. There are more than 500 petrochemical projects planned by 2030 in China, of which three quarters are already under construction, according to data provider GlobalData.

As such, the emissions growth in the chemical sector is poised to continue in the next few years, whereas meeting China’s 2030 targets and commitments would require either reining it in and bringing emissions back down before 2030, or achieving emission reductions in other sectors that offset the increases.

The expansion of the coal-to-chemicals industry is largely driven by projects producing gas and liquid fuels from coal, which make up 70% of the capacity under construction and in planning, according to a mapping by Anychem Coalchem.

These projects are a way of reducing reliance on imported oil and gas. In these areas, electrification and clean energy offer another solution that can replace imports.

Conclusions

The five-year plans being prepared now will largely determine the peak year and level of China’s emissions, with a major impact on China’s subsequent emission trajectory and on the global climate effort.

The targets in the plan will also be a key test of the determination of China’s leadership to respect previous commitments, despite setbacks.

The country has cultivated a reputation for reliably implementing its commitments. For example, senior officials have said that China’s policy targets represent a “bottom line”, which the policymakers are “definitely certain” about meeting, while contrasting this with other countries’ loftier approach to target-setting.

Depending on how the key questions outlined in this article are answered in the plans for the next five years, however, there is the possibility of a rebound in emissions.

There are several factors contributing to such a possibility: solar- and wind-power deployment could slow down under the new pricing policy, weak targets and a deluge of new coal- and gas-power capacity coming onto the market.

In addition, unfettered expansion of the chemical industry could drive up emissions. And climate targets that limit emissions only after a peak is reached could create an incentive to increase emissions in the short term, unless counteracted by effective policies.

On the other hand, there is also the possibility of the clean-energy boom continuing so that the sector beats the targets it has been set. Policymakers could also prioritise carbon-intensity reductions early in the period to meet China’s 2030 commitments.

Given the major role that clean-energy industries have played in driving China’s economic growth and meeting GDP targets, local governments have a strong incentive to keep the expansion going, even if the central government plans for a slowdown.

During the current five-year period, provinces and state-owned enterprises have been more ambitious than the central government. Provinces can and already have found ways to support clean-energy development beyond central government targets.

Such an outcome would continue a well-established pattern, given all previous wind and solar targets have been exceeded by a wide margin.

The difference now is that a significant exceedance of clean-energy targets would make a much bigger difference, due to the much larger absolute size of the industry.

To date, China’s approach to peaking emissions and pursuing carbon neutrality has focused on expanding the supply and driving down the cost of clean technology, emphasising economic expansion rather than restrictions on fossil-fuel use and emissions, with curbing overcapacity an afterthought.

This suggests that if China’s 2030 targets are to be met, it is more likely to be through the over-delivery of clean energy than as a result of determined regulatory effort.

The post Q&A: Five key climate questions for China’s next ‘five-year plan’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: Five key climate questions for China’s next ‘five-year plan’

Climate Change

Cropped 11 March 2026: Iran water worries | Seabed-mining treaty progress | Women farmers and climate change

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Fertiliser disruption in Middle East

FOOD RISKS: The US-Israel war on Iran is “disrupting” the production and export of synthetic fertilisers, reported the Financial Times, which could lead to food price increases. The newspaper noted that the Strait of Hormuz passage, which remains at a near-standstill, is a “crucial shipping route for exports” including urea, sulphur and ammonia – all used in fertilisers. The Guardian noted: “Roughly half of global food production depends on synthetic nitrogen and crop yields would fall without fertiliser.”

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

PLANT FOOD: The fertiliser situation is “especially troubling for farmers in the northern hemisphere” who are beginning to plant their spring crops, said the New York Times. An article in the Conversation said that “even modest reductions in nitrogen use can produce disproportionately large declines in yield”. Elsewhere, a Carbon Brief Q&A looked at the impacts of the war on the energy transition and climate action.

WATER WORRIES: Water – already in short supply in Iran, where long-running droughts have been exacerbated by climate change – has come into renewed focus in the conflict. Bloomberg columnist Javier Blas said water could become the “geopolitical commodity that decides the war”. Desalination plants came “under attack” in Iran and Bahrain, reported the New York Times. These types of plants offer the “only reliable water source for millions across the Arabian Peninsula”, said the Independent.

Negotiations of seabed mining resume

LEGAL BRIEF: The International Seabed Authority (ISA)’s Legal and Technical Commission held a meeting in late February, where they made “progress” in reviewing applications for deep-sea mining exploration and the development of regional environmental management plans, according to an ISA press release. The ISA’s 36-member governing council is currently in Jamaica for a two-week meeting to discuss the future of deep-sea mining in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

NEW RULEBOOK: The New York Times interviewed Leticia Carvalho, head of the ISA, who said the long-awaited deep-sea mining rulebook should be finalised by the end of this year. She said the Trump administration’s push for deep-sea mining is making such an agreement more urgent than ever. However, Grist said that an advocate from French Polynesia said that he does not expect the regulations to be finalised this year, as there are several agreements and discussions pending, including on environmental protections.

INDIGENOUS DEMANDS: Indigenous advocates, who have long worked for their rights to be included in seabed mining regulations, are “bracing for the outcome” of the Jamaica meeting, reported Grist. Some fear that the incorporation of Indigenous rights into those regulations will be dismissed, as has happened previously, said the outlet.

News and views

- LAWS OF NATURE: The EU court of justice fined Portugal €10m (£8.7m) for “failing to comply with environmental laws that require it to protect biodiversity”, according to the Guardian. The newspaper said the country will be penalised until the 55 unprotected sites are protected under EU biodiversity law.

- BURIED REPORT UNCOVERED: Last week, a group of scientists and experts released a draft assessment about the health of nature in the US that had been cancelled by the Trump administration last year, according to the New York Times. The report is “grim, but shot through with bright spots and possibility”, said the outlet.

- ‘BI-OCEANIC’ RAIL: Experts are concerned about the potential social and environmental impacts of a train “mega-project” between Peru and Brazil, reported Mongabay. One researcher told the outlet that the possible rail routes, which cross through the Amazon rainforest, could cause “colossal environmental damage”.

- CLIMATE COOPERATION: India and Nepal signed an agreement to strengthen transboundary cooperation in topics such as climate change, forests and biodiversity conservation, reported the New Indian Express. The collaboration will include the restoration of wildlife corridors and knowledge exchanges, the outlet said.

- REPORT CARD: Carbon Brief analysis showed that half of the world’s countries met a 28 February UN deadline to report on national efforts to tackle nature loss. As of 10 March, 123 countries out of 196 had submitted their national reports, which will inform nature negotiations in Armenia later this year.

- CROP LOSSES: Down To Earth covered a study finding that a “deadly” virus is threatening cassava crops in parts of Africa, partly due to climate change. Meanwhile, Carbon Brief updated an interactive map showing 140 cases of crops being destroyed by heat, drought, floods and other extremes in the past three years.

Spotlight

Women farmers in a warmer and unequal world

International Women’s Day occurs every year on 8 March. Carbon Brief explores the impacts of climate change and gender inequality on women farmers and how they are adapting to a warming planet.

Women farmers play an essential role in global food supply.

According to a report from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), around 36% of working women in 2019 were engaged in agri-food systems. On average, they earned 18% less than men in that sector.

The report found that women working in agriculture tend to do so “under highly unfavourable conditions”, including in the face of “climate-induced weather shocks”.

Typically, women farmers are concentrated in the poorest countries, produce less-lucrative crops and are often unpaid family workers or casual workers in agriculture, the report said.

Vulnerabilities

Research has shown that women farmers are more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change than men.

In Africa and Asia, for example, a 2023 study found that “climate hazards and stressors…tend to negatively affect women [in agri-food systems] more than men”. This is because gender inequality – in the form of discriminatory gender roles or unequal access to resources – is most pronounced in those regions, the study said.

A 2025 study focusing specifically on the Sleman region of Indonesia found that 63% of women farmers suffered from food insecurity due to vulnerability to climate change. This arises from both frequent exposure to drought and low ability to respond to climate impacts, the study explained.

Geraldine García Uribe has been a farmer at the U Neek’ Lu’um agroecology school in Yucatán, Mexico, since 2023. She told Carbon Brief:

“When you have fixed [planting and harvesting] cycles and you start to see changes in the climate – longer droughts or changes in rainfall patterns – plants take longer to grow and pests start to arrive, and that affects the farmers’ pockets and the livelihoods of [their] families.”

She added that women farmers also face inequalities when it comes to deciding how to manage agricultural lands:

“When government support comes, they take [women] less into account because, in general, there are more men present at meetings.”

Adaptation needs

Women farmers face constraints that make them less able to adapt to climate change, according to the FAO report. For example, the working hours of women farmers “decline less than men’s during climate shocks such as heat stress”, said the report.

Josselyn Vega has been farming on her own agroecology farm in Cotopaxi, Ecuador, for three decades. In the Andean region comprising Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru, droughts and floods are frequent, but there are also frosts which, although expected to decrease with climate change, cause crop losses and can have a “drastic” impact on the local economy, according to the Adaptation Fund.

Vega told Carbon Brief that her farm has used “living barriers” to help protect from weather extremes:

“Living barriers are a wall of forest and fruit trees [that] block the wind and prevent drought and frost from passing through.”

The 2023 study recommended that transforming agri-food systems into fairer and more sustainable ones requires reducing and preventing gender inequality.

At the international level, countries have an agreement to implement climate solutions that take women into account, including women farmers. At the most recent UN climate negotiations in Belém, Brazil, countries adopted a new gender action plan, which will last nine years and encourages countries to develop climate policies and plans with a gender perspective.

Vega said that public policies are needed to empower women farmers and ensure that they are included in decision-making. She told Carbon Brief:

“We need to benefit from something that encourages us to continue planting and caring for the land.”

Watch, read, listen

CASH CUTS: In a four-part series, BioGraphic explored how US federal funding cuts have impacted biodiversity and conservation.

RIGHT WHALE ROLLBACK: A News Center Maine video looked at how the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is considering rolling back a rule to protect endangered North Atlantic right whales in the US.

ON THE FARM: “Women farmers are an overlooked force in climate action,” the deputy director of the climate office at the FAO wrote in Reuters.

JUSTICE: Drilled marked the 10-year anniversary of the murder of Indigenous leader Berta Cáceres and looked at why Honduras is “still so dangerous for environmental activists”.

New science

- Large-scale reforestation in different parts of the world could bring “robust net global cooling” of -0.13C to -0.25C | Communications Earth & Environment

- Insects in many parts of the tropics have a “limited capacity” to deal with future projected warming levels | Nature

- The flowering time of tropical plant species has changed by an average of two days per decade since 1794 due to climate change | PLOS One

In the diary

- 9-19 March: Part one of the 31st session of the International Seabed Authority | Kingston, Jamaica

- 15 March: Republic of the Congo presidential election

- 22 March: World Water Day

- 23-29 March: Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals COP15 summit | Campo Grande, Brazil

- 23 March-2 April: Third session of the preparatory commission for the High Seas Treaty | New York

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 11 March 2026: Iran water worries | Seabed-mining treaty progress | Women farmers and climate change appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Paris Agreement watchdog weighs action against countries missing climate plan

The Paris Agreement’s official oversight body is set to decide this month how to deal with over 60 countries that have still not submitted updated national climate plans, over a year after the deadline.

Composed of 12 experts from different regions of the world, the little-known Paris Agreement Implementation and Compliance Committee (PAICC) is tasked with ensuring that nations respect their obligations under the landmark 2015 climate accord.

The Paris Agreement requires each signatory government to submit climate plans known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs), setting out how they will help limit global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

Governments also agreed in Paris that NDCs should be updated every five years and submitted 9–12 months before the next UN climate summit. For COP30, that deadline was 10 February 2025. But, over a year after that deadline, sixty-two countries have not yet produced an updated NDC including significant emitters like India, Vietnam, Argentina and Egypt.

PAICC cannot punish countries, but it can publicly reprimand them for their failure to file new NDCs and other transparency reports and ask them to explain themselves.

Concern over lack of responses

After the overwhelming majority of nations missed the February 2025 deadline to submit their NDCs, PAICC opened over 170 separate cases to engage with governments on why they had not yet issued a climate plan and what steps they were taking to address the delay. Cases are closed once countries submit their NDCs.

While the majority of countries responded to the panel’s enquiries, the PAICC’s annual report said that over 45 nations had failed to provide any information by October 2025. This raised the committee’s concern.

A PAICC member who did not wish to be named told Climate Home News that, while efforts to maintain an open dialogue will continue, the committee will now also discuss how to proceed further with countries that remain out of step with their commitments under the Paris Agreement. The committee will hold a meeting in the German city of Bonn, home to the UN climate change body, between 24-27 March.

“This is a new era, so every step we take we do it for the first time,” they said, adding that the actions the committee will take may vary from country to country, taking into account their individual circumstances.

Deciding next steps

Governments defined the committee’s mandate at COP24 in Katowice, Poland, in 2018 and produced a list of “appropriate measures” it can take to promote compliance with the Paris Agreement. Those include helping countries access technical help or finance, recommending the development of an action plan or “issuing findings of fact” when a country fails to submit an NDC.

The PAICC member said the committee still needs to determine exactly what the last option means in practice, but it will likely take the form of a public statement identifying countries that have failed to comply. The panel could potentially take other actions beyond those listed in its mandate as long as they are not punitive or adversarial.

“The legal obligations [of the Paris Agreement] are few and far between, so it is even more important to keep tabs on whether countries respect them,” the PAICC member added.

Andreas Sieber, head of political strategy at campaigning group 350.org, said national climate plans are “the currency of the Paris Agreement and how the world tracks progress and how countries plan their transitions”.

“Countries, especially the largest emitters, must honour their obligations under the Paris Agreement and submit credible NDCs,” he told Climate Home News, adding that the same applies to wealthy nations that have pledged climate finance.

Many reasons for delays

Many of the governments that have not yet submitted NDCs are low-emitting small or poorer nations, especially in Africa. But major economies that have not issued an updated climate plan – some of which also have energy transition deals with donors – include Egypt, the Philippines and Vietnam.

Countries without a new NDC contribute to 22% of global greenhouse gas emissions, according to data compiled by ClimateWatch.

In their discussions with PAICC over the past year, countries have cited a range of reasons for the delays, including financial constraints, technical challenges, limited data, changes in government, political instability and armed conflicts, according to the committee’s annual report.

India is the largest emitter without an NDC. At COP30 last November, the Indian government said that it would submit its climate plan “on time”, with environment minister Bhupender Yadav telling reporters it would be delivered “by December”. But that self-imposed deadline was not met.

The right-wing government of Argentina, which has considered leaving the Paris Agreement, unveiled caps on the country’s emissions for 2030 and 2035 in an online event on November 3, but has yet to formalise those targets in an NDC.

Undersecretary of the Environment Fernando Brom told Climate Home News that the country would present its NDC during the first week of COP30. That did not happen, although Argentinian negotiators participated in the climate summit.

Some local experts have pointed to the trade deal signed with the US in November as one of the reasons for the delay in submitting the NDC, while others cited the government’s disinterest in the climate agenda.

In January, the Vietnamese government said it was still working on the draft of its NDC, while the Philippines’ government has organised consultation events on its new NDC but has not indicated when it would be released.

The post Paris Agreement watchdog weighs action against countries missing climate plan appeared first on Climate Home News.

Paris Agreement watchdog weighs action against countries missing climate plan

Climate Change

Maui’s Mental Health Crisis Goes Far Beyond the Wildfire Burn Zone

Unstable housing and job loss are key drivers of psychological distress among survivors of the 2023 wildfires, a new study finds. The ripple effects reach across Maui.

On the day of one of the deadliest natural disasters in Hawaii’s history, Blake Kekoa Ramelb watched his hometown go up in flames.

Maui’s Mental Health Crisis Goes Far Beyond the Wildfire Burn Zone

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits