Last week’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) meeting in Hangzhou, China, marked the third time that governments have failed to agree on a timeline for the organisation’s seventh assessment cycle (AR7).

A large group of countries pushed for the reports to be published by the end of 2028, to allow them to feed into the UN’s second global stocktake – a mechanism that will gauge progress towards the Paris Agreement goals.

However, others – including the Chinese hosts – pushed for a longer deadline, warning of “compression in the timeline” that could affect participation, particularly from developing countries.

The meeting ran over by more than 30 hours, meaning that many small delegations – especially small-island developing states and least-developed countries – were unable to stay to the end.

As a result, the final decisions were made without their participation.

According to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB), reporting from inside the meeting, timeline discussions will be taken up again in the next IPCC meeting in late 2025, “with hope that the panel can finally break its deadlock”.

“The absence of a timeline puts potential contributing scientists in a difficult position,” one IPCC scientist tells Carbon Brief.

He notes that the “call for authors” will open soon, but warns how challenging it will be to accept a nomination “if there is no clarity on when a massive time commitment for the IPCC is expected”.

The meeting also saw outlines agreed for AR7’s three main reports – despite the “entrenched positions” of some delegations “complicating efforts to find consensus”, the ENB reports.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, IPCC chair Prof Jim Skea says the process was “probably the most difficult session I can recall”.

In a further complication, reports emerged ahead of the meeting that US officials had been denied permission to attend and a contract for the technical support unit of one of the working groups had been terminated.

It was the first US absence in IPCC history.

Skea says that the IPCC will “have to start thinking more seriously” about how to manage a potential US withdrawal, but the priority last week had been to “get through” the meeting and its lengthy agenda.

He adds that the IPCC has still “had no formal communication from the US at all”.

Below, Carbon Brief unpacks the deliberations at the meeting and the decisions that were made.

- Splits in Sofia

- US no-show

- AR7 schedule

- Assessment report outlines

- CDR report

- Expert meetings

- China host

Splits in Sofia

IPCC “sessions” are meetings that bring together officials and experts from member countries and observer organisations.

Collectively, they decide on the work of the IPCC, including the scope, outline and timeline for reports – all overseen by the IPCC’s “bureau” of elected scientists.

With its sixth assessment report (AR6) completed in 2023, the focus of the IPCC has turned to the seventh assessment (AR7) and the reports it will deliver over the next five years.

At its meetings in Istanbul and Sofia in 2024, the IPCC agreed that AR7 should include – among other outputs – the traditional set of three “working group” reports, one “special” report on cities and two “methodology” reports on “short-lived climate forcers” and “carbon dioxide removal technologies, carbon capture utilisation and storage”.

The three working group reports – each typically running to thousands of pages – focus on climate science (WG1), impacts and adaptation (WG2) and mitigation (WG3).

However, the timeline for these reports was not agreed at either meeting. Countries were split on whether the working group reports should be published in time to inform the UN’s second global stocktake, which will be completed in 2028. The stocktake will gauge international progress towards the Paris Agreement goals. (See: AR7 schedule)

The final decision on the AR7 timeline was, thus, postponed to 2025. As a result, the Hangzhou meeting would need to revisit the timeline – as well as approve the scope and outline of the working group reports themselves.

The Hangzhou meeting, originally slated for five days over 24-28 February, brought together almost 450 participants from governments, international organisations and civil society – including 300 delegates from 124 member countries and 48 observer organisations.

IPCC chair Prof Jim Skea tells Carbon Brief that the agenda contained “six days’ worth [of items] rather than five” and they “started with three sessions a day right from the beginning to try and get ahead”.

US no-show

Just a few days before the meeting opened, Axios reported that government officials from the US had been “denied” permission to attend. Furthermore, it said, the contract for the technical support unit for WG3 had been “terminated” by its provider NASA, meaning its staff “will also not be traveling to China or supporting the IPCC process moving forward”.

(Each working group has a technical support unit, or TSU, which provides scientific and operational support for report authors and the group’s leadership.)

In further reporting, Nature quoted a NASA spokesperson, who said that the move was prompted by guidance “to eliminate non-essential consulting contracts”. The Washington Post reported that the group of 10 TSU staff “still have their jobs…but have been blocked from doing any IPCC-related work since 14 February”. Bloomberg added that WG3 co-chair and NASA chief scientist Dr Kate Cavlin would also not attend the meeting.

Axios speculated that the move “could be the beginning of a bigger withdrawal from US involvement in international climate science work”.

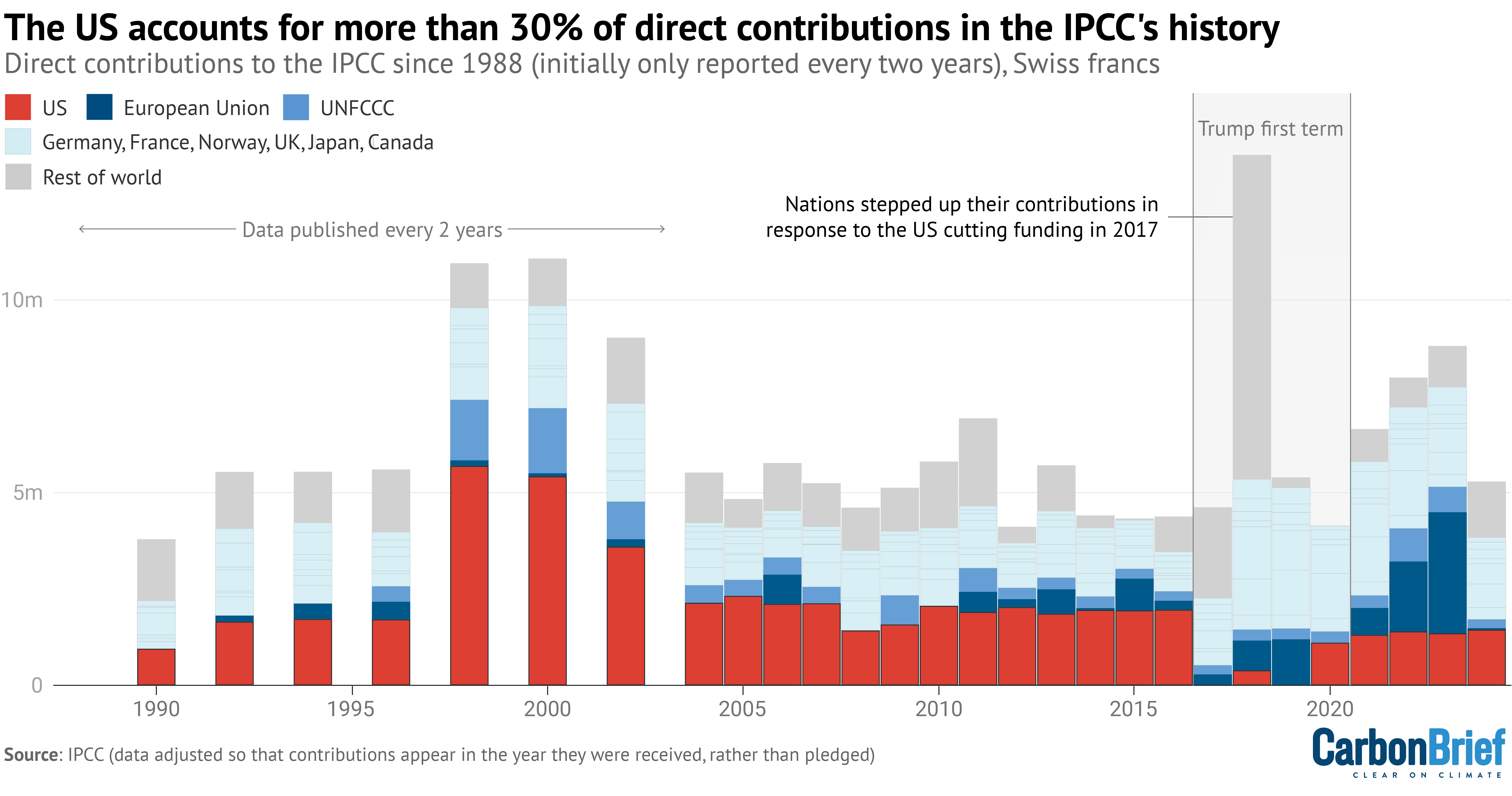

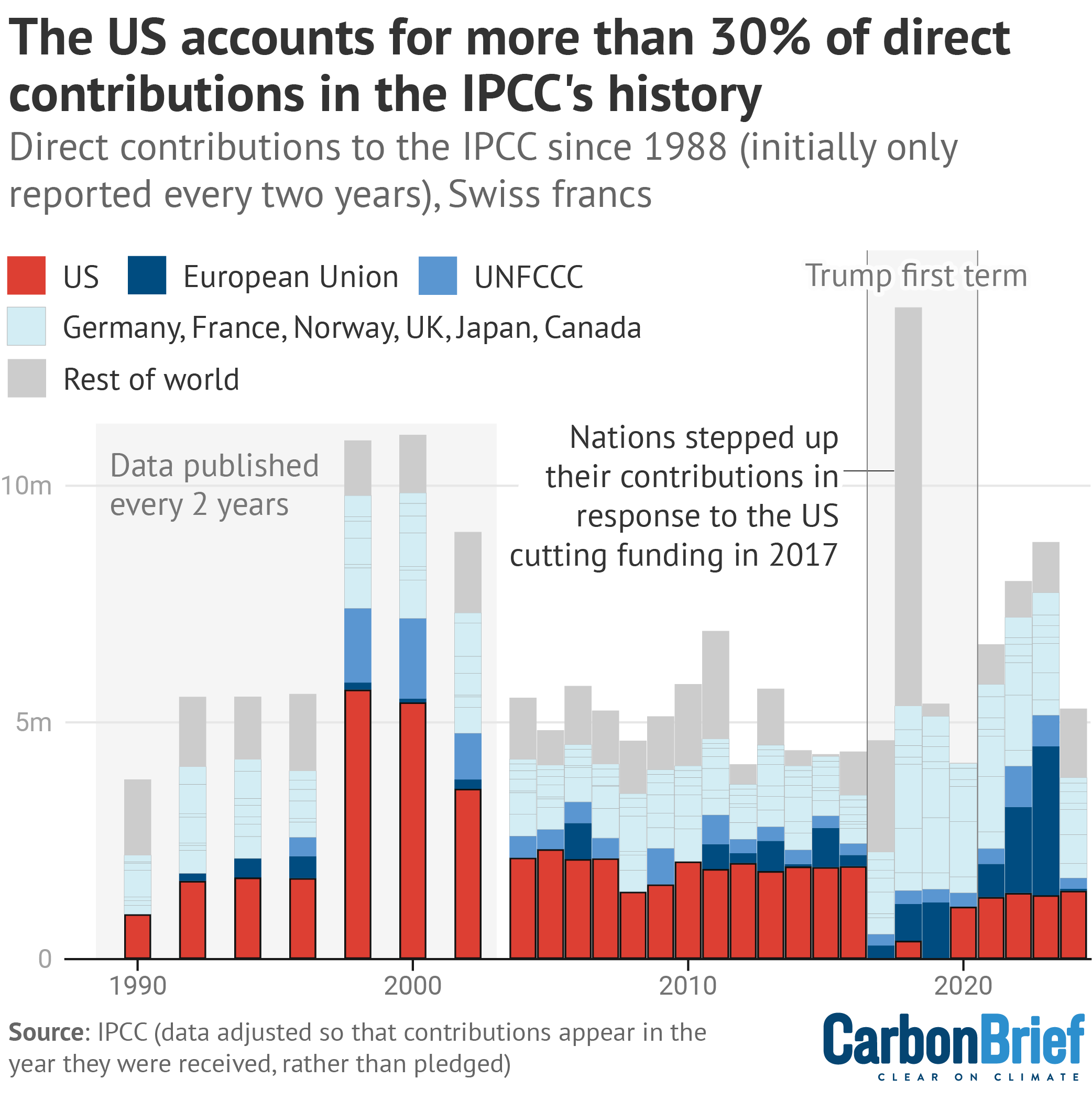

Carbon Brief analysis suggests that the US has provided around 30% of the voluntary contributions to IPCC budgets since it was established in 1988. Totalling more than 53m Swiss francs (£46m), this is more than four times that of the next-largest direct contributor, the European Union.

The first Trump administration cut its contributions to the IPCC in 2017, with other countries stepping up their funding in response. The US subsequently resumed its contributions.

Chart showing the 10 largest direct contributors to the IPCC since its inception in 1988, with the US (red bars), European Union (dark blue) and UNFCCC (mid blue) highlighted. Grey bars show all other contributors combined. Source: IPCC (2025) and (2010). Contributions have been adjusted, as per IPCC footnotes, so they appear in the year they are received, rather than pledged.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Skea says the absence of the US at the meeting itself “didn’t disturb the basic way that the meeting operated”. He adds:

“Every meeting we have 60 countries that don’t turn up out of our membership – the US was now one of that group. I mean, frankly, nobody within the meeting mentioned the US absence. We just got on and did it.”

On the longer-term implications, Skea says that “we didn’t spare an awful lot of time for thinking about”. However, the IPCC will “have to start thinking more seriously” once they have more information, he says, noting that “we have had no formal communication from the US at all”.

Regarding the WG3 TSU, there is no “comparable circumstance” in the IPCC’s history, Skea says. Typically, the co-chair from a developed country is “supposed to bring support for a TSU with them”, he says. (Each working group has two co-chairs – one from a developed country and one from a developing country.) However, the WG3 TSU is already partly supported in Malaysia, where co-chair Prof Joy Jacqueline Pereira is based.

(As an IPCC progress report for the Hangzhou meeting points out, the WG3 TSU has already “taken shape”, although it is not yet fully staffed. The “node” in Malaysia was established with the donor support of the US, Norway and New Zealand. There is also a job advert for a “senior science officer” in the WG3 TSU currently on the IPCC’s website.)

Skea suggests that the situation can be resolved with “creative solutions”, adding that the IPCC “can take any decision, regardless of past principles or past decisions. So I think, with ingenuity, there will be ways around it.”

Prof Frank Jotzo, a professor of environmental economics at the Australian National University’s Crawford School of Public Policy and WG3 lead author on AR5 and AR6, describes the situation as “highly unusual”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“I would expect that other developed countries will come to the rescue to fund the WG3 TSU, to rescue the process and to demonstrate that Trump will not upend this multilateral process. Staff positions could then presumably be either in those countries or in Malaysia, home of the other WG3 co-chair.”

On the US involvement in the IPCC more broadly, CNN reported the comments of a “scientist involved in the report”, who said they were “not sure” what the block on US officials will mean for the planned work going forward, or “if US scientists will participate in the writing of the IPCC reports”.

Science reported that, although US contributions to the IPCC are “typically run out of the White House by the Global Change Research Programme, NASA is the lead on managing GCRP’s contracts”. It added that “NASA leadership, not GCRP, decided to end the TSU contract”.

Following the China meeting, member states are set to solicit nominations of scientists to author the working group reports in AR7, Science explained:

“GCRP usually runs the process [for the US], but the administration’s moves have some wondering whether it will proceed as normal. If not, IPCC does allow scientists to self-nominate without their country’s involvement. But US authors might be shut out anyway if travel funding ends.”

For example, the US nominated 250 scientists to be authors on the special report on cities, which will be part of the AR7 cycle. (Authors can also be nominated by other countries, observer organisations and the IPCC bureau.)

Dr Gavin Schmidt, director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, posted on social media last week that, “despite some reports, there is no blanket prohibition on US scientists interacting with or serving with the IPCC”.

AR7 schedule

A key agenda item for the Hangzhou meeting was to finalise the timeline for publishing AR7 reports. This is a contentious point on which delegates were unable to reach an agreement at either the Istanbul or Sofia meetings.

Heading into the meeting, countries were split on whether the working group reports should be published in time to inform the UN’s second global stocktake, which will be completed in 2028.

In the IPCC plenary on Saturday afternoon, Skea emphasised the “enormous effort and time” taken over this decision – including during the scoping meeting at Kuala Lumpur – and stressed the importance of an integrated approach to planning across the three working groups.

The working head of the WG2 TSU put forward the proposed schedule for AR7 cycle, which would see all working group reports published in time to feed into the second global stocktake in 2028.

A long list of countries underscored the importance of a “timely, policy-relevant” AR7 cycle, urging the adoption of the schedule put forward by the IPCC bureau in order to avoid failing to reach an agreement, according to the ENB. These included the UK, EU, Australia, Japan, Luxembourg, Turkey and Jamaica. (Jamaica was speaking on behalf of the other small island developing states who were unable to stay past the scheduled close of the plenary session.)

However, India, Saudi Arabia, Algeria and South Africa called for the schedule to be revised, citing “time compression in the timeline and challenges for scientists from developing countries to produce literature”, the ENB reports. And Kenya “expressed concern about inclusivity and called for more flexibility on timing”.

At this point, many countries raised concern about the number of countries who had already left the session, with Australia noting that “many of them are precisely those who lack capacity and depend on IPCC’s assessments”.

Skea stressed the need to agree a timeline in this meeting so that work on the main reports – including author selection – could progress. Discussions continued in a huddle throughout Saturday afternoon and into the evening.

Late on Saturday evening, Italy and Ireland, supported by a handful of other countries, suggested an additional option to stretch the timeline to allow an extra month of “wiggle room”.

However, India and South Africa “said the addition of one or two months did not make it a viable counter-suggestion”, according to the ENB. The three countries instead suggested completing the WG1 report by July 2028, WG2 in December 2028, WG3 in April 2029 and the synthesis report in the second half of 2029.

To move forward, Skea proposed agreeing on the outlines of the working groups and inviting experts to start their work, including putting out the call for author nominations and convening the first lead authors meeting in 2025. However, he said that the timeline decision would be deferred until the next IPCC meeting in late 2025.

Skea tells Carbon Brief that the meeting was helpful for “clarifying where different groups of countries were coming from”. He says that the opposition to a stocktake-aligned timeline was “not about the outcome and the synchronisation with the political process”, but, rather, “the needs of countries for doing their reviews of the [report] drafts – how frequently, how rapidly, they were coming”.

Even with the two options – a proposed timeline and a counter suggestion – resolving remaining differences won’t be “easy”, Skea says, adding that “I think we will be off to do a little bit of consultation offline before we get to IPCC-63 to see how we resolve it”.

“The absence of a timeline puts potential contributing scientists in a difficult position,” Rogelj tells Carbon Brief. He adds:

“My understanding is that a call for authors will be launched soon. However, how can one accept a nomination or subsequent selection if there is no clarity on when a massive time commitment for the IPCC is expected. It shows how political games regarding the timing of scientific evidence for the negotiations dominate considerations for authors and considerations of delivering the best possible report.”

WG2 co-chair Prof Bart van den Hurk tells Carbon Brief that the failure to agree on a timeline means that experts invited to take part in reports “will not receive a schedule for all the meetings they’re supposed to attend”, leading to possible agenda clashes later.

It also means that they “don’t know for how long they’re signed up for this time-intensive yet voluntary role, which is a big ask”, he adds.

Assessment report outlines

Heading into the Hangzhou meeting, countries had agreed to produce a full set of assessment reports with a synthesis report, along with a special report on climate change and cities and two methodology reports.

The scope, outlines and titles for WG1, WG2 and WG3 reports were prepared at a meeting in Kuala Lumpur in December 2024, to be reviewed and approved in Hangzhou.

At the scoping meeting, some experts suggested that reports should include “plain-language summaries”, because local authorities, companies and the general public often do not know the “jargon”, the ENB reports.

When brought to the Hangzhou meeting, countries including Australia, France and Vanuatu supported this suggestion, stressing the importance of accessibility. Some countries also called for shorter reports focused on new science.

However, the Russian Federation, India and Saudi Arabia were opposed, the ENB says. The Russian Federation argued that the report is intended for an expert audience and India said that these summaries “would compete with the [summary for policymakers] and IPCC outreach mechanisms”, adding that any plain-language summaries would need to be approved line-by-line.

Later, the WG1 co-chairs suggested changing “plain-language summaries” to “plain-language overviews,” in which authors provide a chapter overview, including graphics, in a similar manner to the FAQs sections.

About 20 countries, including the UK, Canada, Ukraine, Chile, China and Libya, supported the suggestion. However, Algeria, Russian Federation, India and Saudi Arabia continued to oppose it, the ENB says.

A “huddle” was convened to find consensus, which, ultimately, agreed to delete any reference to “plain language overviews” and instead encouraged authors to ensure that the executive summary of each report is clear.

The countries then discussed the proposed outline for each working group report in turn. Skea tells Carbon Brief that this process “had some of the quality of an approval session” for a finished report, adding:

“But people did compromise in the end and we did get the outlines of the reports agreed, which, for me, was the real objective of the meeting.”

For WG1, many countries welcomed the proposed outline and some suggested changes. For example, Switzerland called for addressing the unique challenges faced by high altitude and latitude environments. And India asked for the inclusion of a chapter on monsoons and deletion of a chapter on climate information and services, the ENB says.

When discussing the chapter on abrupt changes, tipping points and high-impact events in the Earth system, Saudi Arabia and India objected to singling out “tipping points” in the title and suggested deleting them, the ENB says. However, Switzerland, supported by a handful of other countries, highlighted their relevance for policy and science and called for them to be kept in.

On Friday, after a huddle, the title was changed to: “Abrupt changes, low-likelihood high-impact events and critical thresholds, including tipping points, in the Earth system.”

Delegates agreed on the following chapters for the WG1 report:

- Chapter 1: Framing, methods and knowledge sources;

- Chapter 2: Large-scale changes in the climate system and their causes;

- Chapter 3: Changes in regional climate and extremes and their causes;

- Chapter 4: Advances in process understanding of Earth system changes;

- Chapter 5: Scenarios and projected future global temperatures;

- Chapter 6: Global projections of Earth system responses across time scales;

- Chapter 7: Projections of regional climate and extremes;

- Chapter 8: Abrupt changes, low-likelihood high impact events and critical thresholds, including tipping points, in the Earth system;

- Chapter 9: Earth system responses under pathways towards temperature stabilisation, including overshoot pathways; and

- Chapter 10: Climate information and services.

On the WG2 report outline, Kenya said AR6 definition of maladaptation is “limiting” and called for the term to be redefined for the new report, the ENB says. Meanwhile, Brazil and Switzerland called for the report to assess the risks of solar radiation management, given its cross-cutting nature and potential impacts on sectors, such as agriculture.

Senegal underscored the need for a focus on losses and damages, expressing hope that this will “help showcase those in greatest need”. And Saudi Arabia called for a full assessment of the potential of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies.

Delegates agreed on the following chapters for the WG2 report:

Global assessment chapters:

- Chapter 2: Vulnerabilities, impacts and risks;

- Chapter 3: Current adaptation progress, effectiveness and adequacy;

- Chapter 4: Adaptation options and conditions for accelerating action;

- Chapter 5: Responses to losses and damages; and

- Chapter 6: Finance.

- Chapters 7-13 are regional assessment chapters on Africa, Asia, Australasia, Central and South America, Europe, North America and small islands.

Thematic assessment chapters:

- Chapter 14: Terrestrial, freshwater and cryospheric biodiversity, ecosystems and their services;

- Chapter 15: Ocean, coastal, and cryospheric biodiversity, ecosystems and their services;

- Chapter 16: Water;

- Chapter 17: Agriculture, food, forestry, fibre and fisheries;

- Chapter 18: Adaptation of human settlements, infrastructure and industry systems;

- Chapter 19: Health and well-being; and

- Chapter 20: Poverty, livelihoods, mobility and fragility

Among the comments on the WG3 outline, the Russian Federation cautioned against discussing national policies – describing this as “beyond [WG3’s mandate], the ENB says. Belgium suggested including social tipping points in the report, the ENB says, while Saudi Arabia argued the IPCC reports “should be neutral with respect to policy and called for a full assessment of the potential of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technologies”.

Delegates agreed on the following chapters for the WG3 report:

- Chapter 1: Introduction and framing;

- Chapter 2: Past and current anthropogenic emissions and their drivers;

- Chapter 3: Projected futures in the context of sustainable development and climate change;

- Chapter 4: Sustainable development and mitigation;

- Chapter 5: Enablers and barriers;

- Chapter 6: Policies and governance and international cooperation;

- Chapter 7: Finance;

- Chapter 8: Services and demand;

- Chapter 9: Energy systems;

- Chapter 10: Industry;

- Chapter 11: Transport and mobility services and systems;

- Chapter 12: Buildings and human settlements;

- Chapter 13: Agriculture, forestry and other land uses (AFOLU);

- Chapter 14: Integration and interactions across sectors and systems; and

- Chapter 15: Potentials, limits and risks of carbon dioxide removal.

CDR report

Among the other items on the Hangzhou agenda was the finalisation of the scope and outline of a methodology report on carbon dioxide removal (CDR) and carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) technologies, slated for publication in 2027.

At a scoping meeting held in Copenhagen in October, the IPCC’s task force on national greenhouse gas inventories – which is coordinating the methodology report – agreed on a title, scope and outline for the forthcoming report.

Delegates in Hangzhou failed to reach agreement on the plan for the report, after disagreements emerged around chapter seven of the proposed outline – which looks at carbon removals from oceans, lakes and rivers.

A number of delegations – including India, France, Belgium, Chile and Turkey – objected to the inclusion of a standalone chapter in the methodology report on carbon removal from waterbodies, the ENB says. The countries argued there is insufficient understanding of the environmental impacts and effectiveness of certain marine CDR technologies, including ocean alkalinity enhancement.

Saudi Arabia was among the countries that argued in favour of a chapter on carbon removal from waterbodies. The Gulf nation said that its removal would set a “worrying precedent” and be a “bad sign” for emerging technologies, according to the ENB.

With no consensus reached, delegates agreed on the title and chapters one to six of the report, but postponed further deliberations on chapter seven until the next plenary meeting.

IPCC chair Skea tells Carbon Brief that delegates “were extremely close to getting agreement” on the report, but had been hampered by a lack of “ingenuity and time”.

He adds that a solution which helped broker agreement on the outline for the special report on short-lived climate forcers at the last IPCC plenary meeting could offer a path forward for the methodology report. (After a debate arose around the inclusion of hydrogen emissions in that report, country delegations compromised on a footnote stating the matter would be addressed in a future cycle.) Skea explains:

“The [IPCC’s] task force on national greenhouse gas inventories always has this issue as to whether there’s enough scientific evidence to justify bringing a technology or a technique in. If there are doubts about the quality of the basic evidence for bringing it in, there are devices for kicking the can down the road just a little bit.”

Some insiders speculated that the standoff over the methodology report in Hangzhou could have consequences for the overall AR7 timeline. They told Carbon Brief the delay to the report’s start could result in shifted review periods and necessitate an extra approval plenary in 2028.

Expert meetings

A number of expert meetings and workshops were approved in Hangzhou.

This included two workshops designed to explore “new and extended” methods of assessment at the IPCC. One will focus on the incorporation of diverse knowledge systems, including Indigenous and local knowledge, while the other will look at the use of emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence.

An expert meeting on methodologies, metrics and indicators for assessing climate change impacts was also approved.

Proposals to hold an expert meeting on high-impact events and Earth system tipping points, however, proved contentious and were deferred to a later session. Rifts emerged around the concept of “tipping points” and the format of the event, the ENB says.

The lengthy nature of discussions about expert meetings and workshops prompted a number of countries – and IPCC chair Skea – to articulate concerns around the general state of decision-making at the meeting, according to the ENB.

In a “progress report” session where the IPCC bureau updated members on its activities, Saudi Arabia voiced concern about briefings given by the IPCC to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which is drawing up an advisory opinion on states’ climate-related obligations. Skea said that briefings had been limited to “purely scientific” information, the ENB says.

In a session which took place as talks overran into Saturday morning, a number of countries called for greater collaboration between the IPCC and its biodiversity-focused counterpart, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). However, others pointed to the difference between IPBES and IPCC review processes.

China host

The Hangzhou meeting marks the first time an IPCC bureau meeting has been held in China. It is also the first major climate conference hosted by the nation since the Tianjin talks organised by the UNFCCC in 2010 after negotiations faltered at the COP15 climate summit in Copenhagen.

The 34-member IPCC bureau features one scientist from China – meteorologist Dr Zhang Xiaoye, who is co-chair of WG1.

Coverage of the meeting in national and local Chinese media focused largely on statements and comments from government officials, including national climate envoy Liu Zhenmin and spokespeople for the foreign ministry and the China Meteorological Association.

Officials stressed China’s “active” contribution to global climate action, but stopped short of characterising the nation as a climate leader.

For example, in comments captured by the Economic Observer, foreign ministry spokesperson Lin Jian characterised China as a “fellow traveller” in the “green transformation” of the global south.

China Meteorological Administration director Chen Zhenlin said the nation stood willing to “cooperate extensively with all parties to jointly respond to extreme weather and climate risk challenges” and “jointly build a community with a shared future for mankind in the field of climate change”, according to Science and Technology Daily.

A number of Chinese publications – including the Paper, Xinhua and China Daily – reported on closing comments made by IPCC chair Jim Skea, which emphasised China’s critical role in international climate governance.

Yao Zhe, policy analyst at Greenpeace East Asia, says that hosting the conference allowed China to demonstrate “its support for climate science and its genuine interest in continuing international engagement on climate”. However, she tells Carbon Brief that she saw a “gap in expectations”:

“China sees itself mainly as a hospitable host, but others at the conference expect it to help build consensus and take a more progressive stance. I think this points to an emerging question in the broader landscape: The bar for China’s climate leadership will only rise as its influence on climate policy and cleantech markets grows. But when will China be ready to meet these expectations?”

Observers told Climate Home News they had witnessed a disconnect between Chinese officials’ public statements of support for cooperation on climate change and their positions in closed-door negotiations, which included a push to keep the next round of IPCC reports out of the next global stocktake.

On the last official day of the conference, Peru announced its offer to host the next session of the IPCC in the final quarter of this year. The exact date is still to be determined as there is “still some debate about where it sits in relation to COP30 – for example, before or after”, says Skea.

The post IPCC report timeline still undecided after ‘most difficult’ meeting in China appeared first on Carbon Brief.

IPCC report timeline still undecided after ‘most difficult’ meeting in China

Climate Change

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

The country’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas benefited from what critics say is a questionable IRS interpretation of tax credits.

Cheniere Energy, the largest producer and exporter of U.S. liquefied natural gas, received $370 million from the IRS in the first quarter of 2026, a payout that shipping experts, tax specialists and a U.S. senator say the company never should have received.

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

Climate Change

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

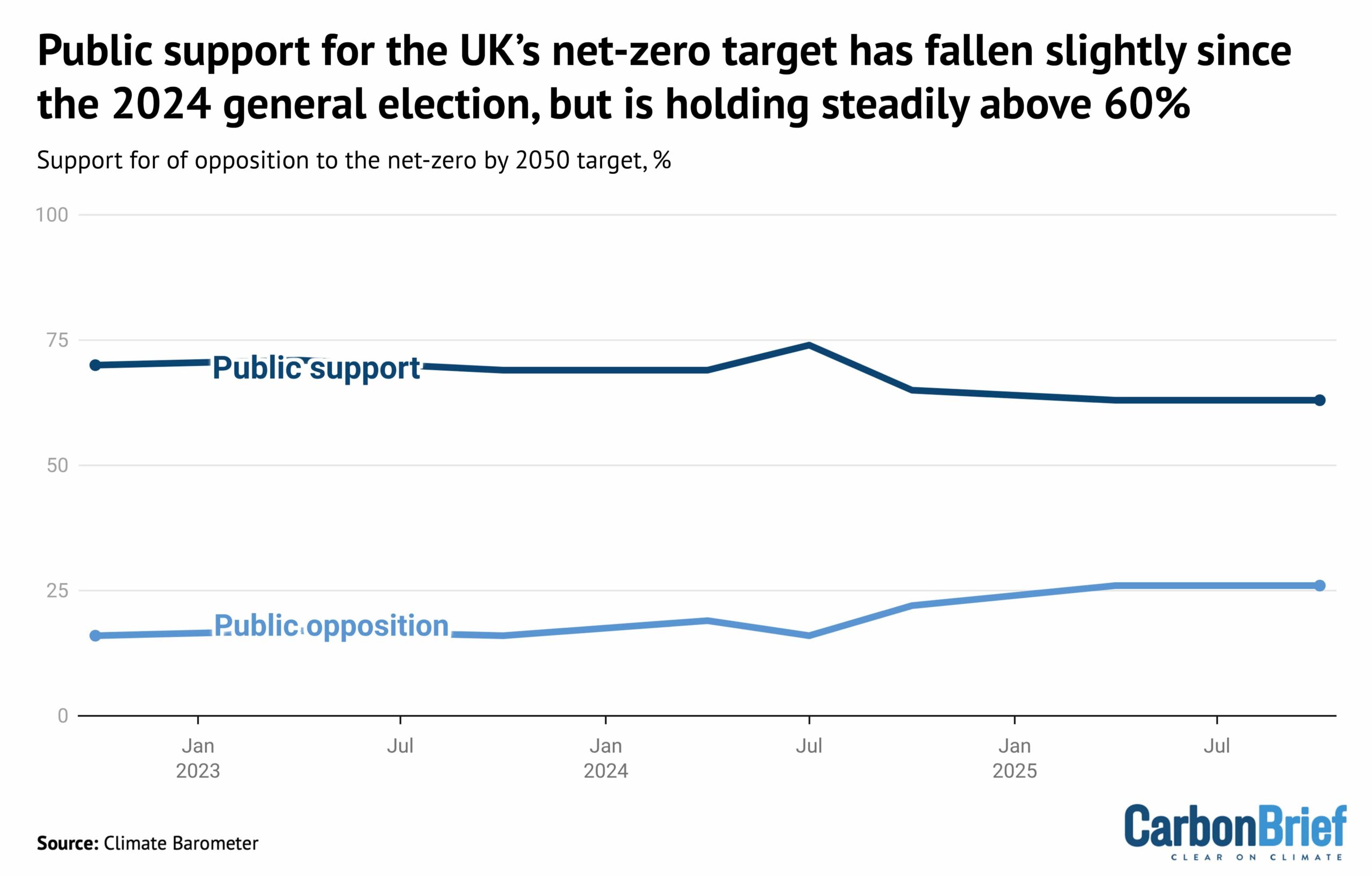

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

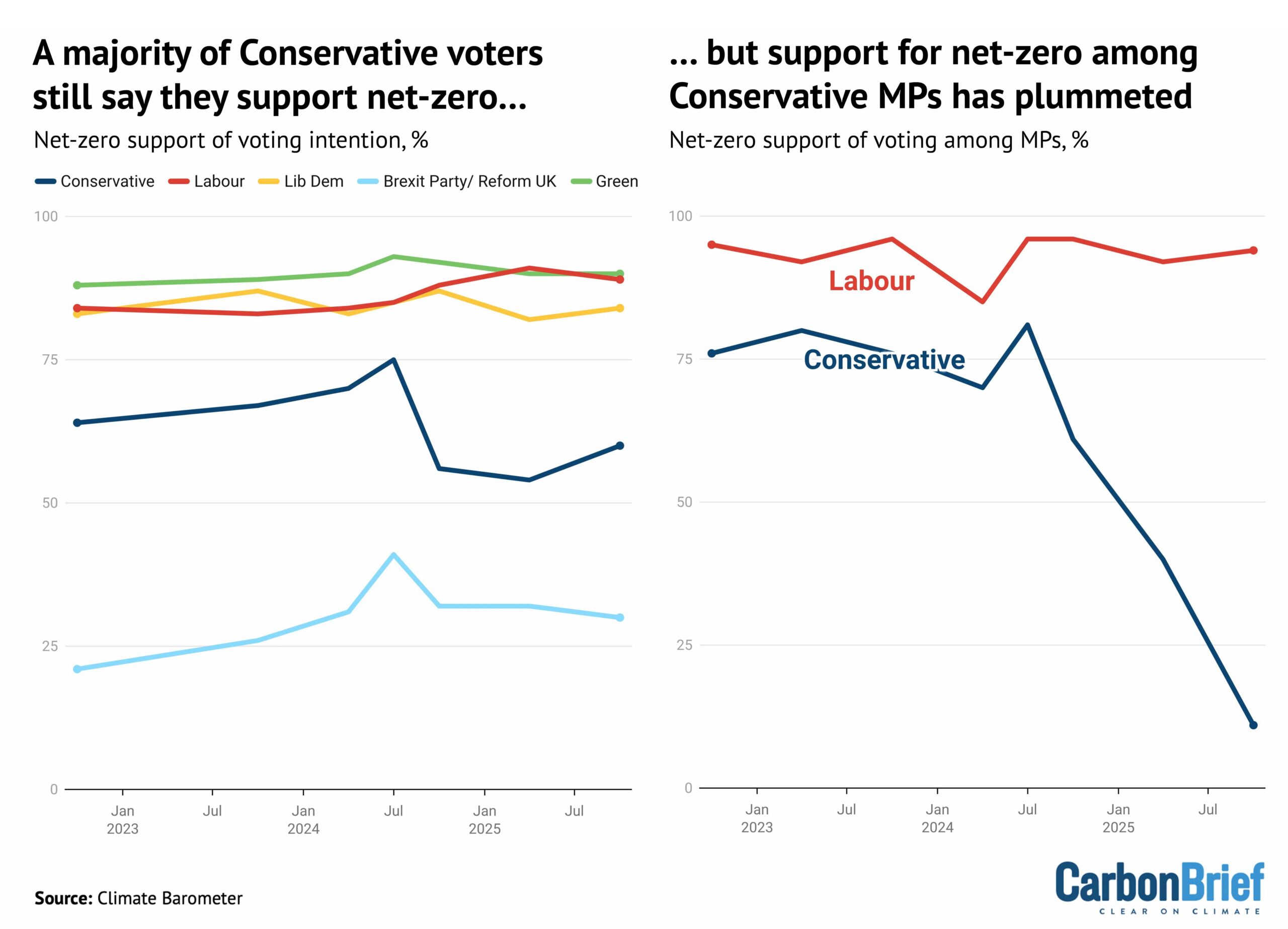

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

Seven Pacific island nations say they will demand heftier levies on global shipping emissions if opponents of a green deal for the industry succeed in reopening negotiations on the stalled accord.

The United States and Saudi Arabia persuaded countries not to grant final approval to the International Maritime Organization’s Net-Zero Framework (NZF) in October and they are now leading a drive for changes to the deal.

In a joint submission seen by Climate Home News, the seven climate-vulnerable Pacific countries said the framework was already a “fragile compromise”, and vowed to push for a universal levy on all ship emissions, as well as higher fees . The deal currently stipulates that fees will be charged when a vessel’s emissions exceed a certain level.

“For many countries, the NZF represents the absolute limit of what they can accept,” said the unpublished submission by Fiji, Kiribati, Vanuatu, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands.

The countries said a universal levy and higher charges on shipping would raise more funds to enable a “just and equitable transition leaving no country behind”. They added, however, that “despite its many shortcomings”, the framework should be adopted later this year.

US allies want exemption for ‘transition fuels’

The previous attempt to adopt the framework failed after governments narrowly voted to postpone it by a year. Ahead of the vote, the US threatened governments and their officials with sanctions, tariffs and visa restrictions – and President Donald Trump called the framework a “Green New Scam Tax on Shipping”.

Since then, Liberia – an African nation with a major low-tax shipping registry headquartered in the US state of Virginia – has proposed a new measure under which, rather than staying fixed under the NZF, ships’ emissions intensity targets change depending on “demonstrated uptake” of both “low-carbon and zero-carbon fuels”.

The proposal places stringent conditions on what fuels are taken into consideration when setting these targets, stressing that the low- and zero-carbon fuels should be “scalable”, not cost more than 15% more than standard marine fuels and should be available at “sufficient ports worldwide”.

This proposal would not “penalise transitional fuels” like natural gas and biofuels, they said. In the last decade, the US has built a host of large liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals, which the Trump administration is lobbying other countries to purchase from.

The draft motion, seen by Climate Home News, was co-sponsored by US ally Argentina and also by Panama, a shipping hub whose canal the US has threatened to annex. Both countries voted with the US to postpone the last vote on adopting the framework.

The IMO’s Panamanian head Arsenio Dominguez told reporters in January that changes to the framework were now possible.

“It is clear from what happened last year that we need to look into the concerns that have been expressed [and] … make sure that they are somehow addressed within the framework,” he said.

Patchwork of levies

While the European Union pushed firmly for the framework’s adoption, two of its shipping-reliant member states – Greece and Cyprus – abstained in October’s vote.

After a meeting between the Greek shipping minister and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister in January, Greece said a “common position” united Greece, Saudi Arabia and the US on the framework.

If the NZF or a similar instrument is not adopted, the IMO has warned that there will be a patchwork of differing regional levies on pollution – like the EU’s emissions trading system for ships visiting its ports – which will be complicated and expensive to comply with.

This would mean that only countries with their own levies and with lots of ships visiting their ports would raise funds, making it harder for other nations to fund green investments in their ports, seafarers and shipping companies. In contrast, under the NZF, revenues would be disbursed by the IMO to all nations based on set criteria.

Anais Rios, shipping policy officer from green campaign group Seas At Risk, told Climate Home News the proposal by the Pacific nations for a levy on all shipping emissions – not just those above a certain threshold – was “the most credible way to meet the IMO’s climate goals”.

“With geopolitics reframing climate policy, asking the IMO to reopen the discussion on the universal levy is the only way to decarbonise shipping whilst bringing revenue to manage impacts fairly,” Rios said.

“It is […] far stronger than the Net-Zero Framework that is currently on offer.”

The post Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen appeared first on Climate Home News.

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits