Climate governance, how societies organize decision-making around climate change, is often framed through Western political and legal structures. These models tend to prioritize human-centric policies rooted in concepts such as property, ownership, and nation-states. Within this framework, the environment is often reduced to a resource to be managed, extracted, or commodified. In contrast, Indigenous climate governance offers an entirely different paradigm, one that is not about dominion over land but about reciprocal relationships, sacred obligations, and the recognition of ecological sovereignty.

It is essential to emphasize that Indigenous Peoples do not require validation, endorsement, or recognition from non-Indigenous institutions to develop, uphold, or practice their governance systems. These frameworks of law and stewardship are rooted in original relationships to homeland ties that precede and transcend colonial boundaries.

The days are numbered for systems that invite Indigenous Peoples to the table only as tokens or symbolic presences, while denying their voices the space and authority to shape outcomes. Indigenous governance is not a matter of permission from others; it is the lived practice of self-determination that every living being on Mother Earth inherits and is responsible for.

What is Indigenous Climate Governance?

Indigenous climate governance is a holistic system of law, custom, and responsibility that places interdependence at its core. It reflects millennia of Indigenous stewardship and an understanding that humans are not the rulers of ecosystems but participants within them. Governance is not defined solely by human authority, but by respect for the natural laws that sustain all life. This worldview recognizes that the land, waters, plants, animals, and spiritual forces all carry agency and rights. Humans are woven into this vast web of relations, with responsibilities of reciprocity and care.

At its foundation, Indigenous climate governance protects the autonomy and vitality of place, which is often referred to as ecological sovereignty. Decision-making is collective, inclusive of all living beings, and guided by natural law rather than anthropocentric legal constructs. In this way, governance is not about imposing human will but about aligning with the rhythms, responsibilities, and teachings of the natural world.

Climate change is, at its root, a crisis of ecological imbalance. Indigenous Peoples who have retained rights to stewardship through origin relationships to place, space, and homeland understand this balance as sacred. They are best positioned to speak with, rather than for, their human and non-human kin regarding the health and well-being of these homelands. This is where the difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous governance lies: the former is grounded in responsibilities to life systems. At the same time, the latter too often assumes authority to determine for others. True governance is not about control but about nurturing the self-determination of people, lands, waters, and ecosystems.

How Indigenous Climate Governance Differs from Western Models

Western climate governance is profoundly influenced by colonial legacies that prioritize property rights, commodity extraction, and human control over land and water. Such frameworks often fragment ecosystems and communities by enforcing borders and legal regimes that treat nature as something to be divided, owned, and exploited. Indigenous governance rejects these constructs and instead insists on a worldview that frames the Earth as a living relative, with inherent rights and sovereignty.

This worldview demands that human actions serve to maintain balance and harmony in ecosystems, rather than disrupt them. Governance is viewed as a set of ongoing relationships founded on care, respect, and mutual responsibility, rather than as systems of domination and control. By refusing to fragment ecosystems with artificial legal and political borders, Indigenous climate governance opens pathways to climate justice that are inclusive, life-sustaining, and grounded in ecological stewardship.

For non-Indigenous Peoples, this requires a willingness to step aside and listen, to witness the story of life being shared through Indigenous knowledge and practice. It means recognizing that democracy itself must be redefined, not as a system of power over others but as a philosophy of coexistence, rooted in the laws of nature. These are the laws that governance is meant to uphold, not jeopardize. Colonization has had the opposite effect: undermining natural law to benefit the few at the expense of the many.

The Building Blocks of Ecological Sovereignty

Ecological sovereignty is the right of Indigenous Nations and the ecosystems they steward to manage and protect their lands and waters in alignment with their laws and values. It is rooted in kinship relations, where plants, animals, waters, and lands are recognized as relatives with their agency to thrive or suffer. This principle is sustained by natural law, which acts as a living constitution that structures coexistence, respect, and accountability among all beings.

Relational governance is another key element. Rather than separating human interests from ecological systems, it binds humans and non-humans together in an interdependent framework of stewardship and decision-making. Cultural protocols and ceremonies ensure that governance remains responsive to the cycles of nature and ancestral teachings, grounding decisions in gratitude, responsibility, and humility. These building blocks together create a framework for sovereignty that extends beyond political recognition into the living fabric of ecosystems.

The Indigenous Constitution of the Land: Laws and Regulations of Peace and Harmony

In many Indigenous Nations, governance of place is carried out through a constitution that is not confined to written text, but is encoded in ceremony, storytelling, and the role of law keepers. These laws emphasize peace, mutual respect, and the ongoing balance of life. Every action must consider its impacts on the land, waters, climate, and all beings. Reciprocity is essential; humans must return to the Earth what they take, ensuring that ecosystems regenerate and remain vibrant for future generations.

This constitution also recognizes the agency of non-human beings, affirming their right to exist, flourish, and govern their own lives. Governance is inclusive and collective, ensuring that the voices of Elders, youth, women, and the land itself are respected and valued. For example, laws may mandate sustainable harvesting, seasonal restrictions, ceremonies of permission and thanksgiving, and rites of care when ecosystems are vulnerable. These protocols are not static but adaptive, responsive to the cycles of place, and always rooted in harmony and respect.

Why Indigenous-Led Climate Governance Matters

Indigenous climate governance offers a profound alternative to Western models of climate decision-making. It is not about control, but coexistence. This shift is critical in addressing the climate crisis because it directly challenges the colonial systems that have fueled ecological destruction and excluded Indigenous Nations from decision-making. By centring Indigenous leadership, governance becomes about multidimensional wellbeing: ecological, cultural, spiritual, and communal health.

It also restores natural laws that protect biodiversity, climate stability, and the rights of all beings. Where Western systems often respond reactively to crises, Indigenous governance emphasizes proactive care, long-term thinking, and intergenerational responsibilities. By embracing these principles, climate justice transforms into a journey toward genuine equity, recognizing Indigenous Nations as sovereign stewards of their lands and waters, with authority that transcends human political boundaries and includes all life.

Blog by Rye Karonhiowanen Barberstock

Image Credit: Igor Kyryliuk and Tetiana Kravchenko, Unsplash

The post Indigenous Climate Governance: Reclaiming Ecological Sovereignty and Redefining Climate Justice appeared first on Indigenous Climate Hub.

Indigenous Climate Governance: Reclaiming Ecological Sovereignty and Redefining Climate Justice

Climate Change

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of America’s Broken Health Care System

American farmers are drowning in health insurance costs, while their German counterparts never worry about medical bills. The difference may help determine which country’s small farms are better prepared for a changing climate.

Samantha Kemnah looked out the foggy window of her home in New Berlin, New York, at the 150-acre dairy farm she and her husband, Chris, bought last year. This winter, an unprecedented cold front brought snowstorms and ice to the region.

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of the Broken U.S. Health Care System

Climate Change

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Two Utah Congress members have introduced a resolution that could end protections for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Conservation groups worry similar maneuvers on other federal lands will follow.

Lawmakers from Utah have commandeered an obscure law to unravel protections for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, potentially delivering on a Trump administration goal of undoing protections for public conservation lands across the country.

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Climate Change

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

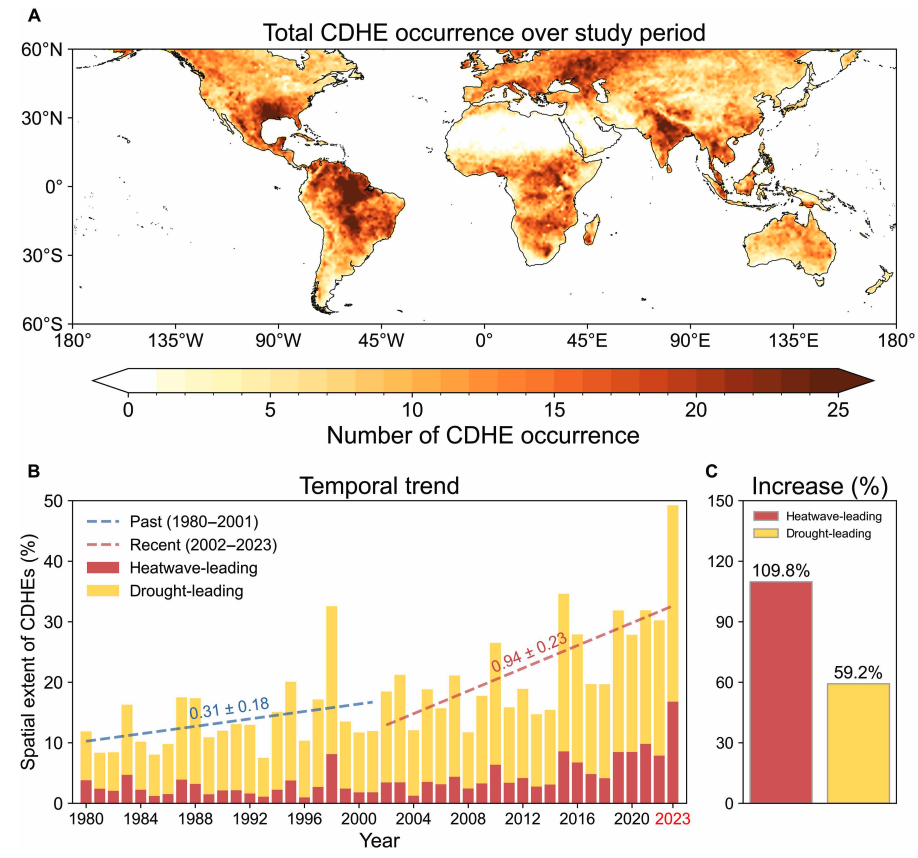

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits