Greetings from Malaysia—Cheow Mei and Max wanted to have a cool Malaysian greeting here, but people here just say “Hi.” Fortunately, English is the second official language in Malaysia, so Max’s Malaysian vocabulary is limited to “Thank you,” “How are you,” and “Hi.“

We, Cheow Mei and Max work together on the GAME project at the Centre for Marine and Coastal Studies (CEMACS). And that’s where some special things come together. CEMACS is part of Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM); the main campus is located in Gelugor, near the 1st Penang Bridge on Penang Island, whereas CEMACS is located in Penang National Park, which is the smallest national park in Malaysia! Travelling to CEMACS itself is a bit of an adventure. First, in whichever transportation we choose to take, we have to go through a long winding road to arrive at the Penang National Park. once we arrive at the national park, the journey continues with a 5-minute boat ride to CEMACS. Of course, we can also choose to hike to CEMACS as there is a hiking trail to CEMACS, which takes about 30 minutes. At more than 30 degrees and a humidity of 70%, this is a sweaty affair (believe us, we do this every weekend).

Believe it or not. Max is actually the first GAME student who managed to experiment in Malaysia for the entire time. Before that, there was the COVID-19 pandemic or problems with the visa, which prevented other GAME participants from coming to Malaysia. So, for the first time since 2020, we have a German-Malaysian tandem in CEMACS. Of the eight teams, we are the southernmost team with a latitude of 5°, which is the closest to the equator of all the teams.

And because of this proximity to the equator, we have a tropical climate with high humidity (which makes you sweat a lot) and very constant temperatures of around 30 degrees. Due to the daytime climate, we have a greater temperature difference between day and night than between the months. And this also influences the day and night rhythm, which is important for our experiments. The further north we go, the greater the difference in length between day and night. Here in Malaysia, we almost always have 12 hours of sun and 12 hours of night throughout the year. During the year, this only changes by 26 minutes.

We are both very excited to see how this will affect our results and how they will compare to other teams in the end. We are now fully immersed in our experiment and are working here with the sea urchin species Temnopleurus toreumaticus (same species as used in GAME 2021) as a grey species to additionally stress our algae, Gracilaria sp. and Caulerpa lentillifera. However, our sea urchins do not grow on trees where we could simply pick them (they are marine creatures, after all). So we had to play fishers: Over several days, we tried our luck with a cast-net, but apart from 2-3 sea urchins, we only caught small fish or crabs. With the help of real fishermen, we were then able to get real sea urchins, which we could use for our pilot studies. One day in June, we were lucky and managed to find more sea urchins, which we are now using for our experiments.

Opposites work well together, right? That’s exactly how it works for us. We started our experiments with a slight time delay so that we could help each other. But there is a huge contrast. Coffee. Max brings freshly brewed coffee to CEMACS every morning, whereas Cheow Mei runs mad with coffee. After lunch, they make another pot in the lab. Initially only for Max, then for another employee, but now half the CEMACS team is in the small GAME lab after lunch to drink coffee, and at least two full pots are made. Hence, the lab’s now unofficial name: Ce-Max Coffeeshop.

As the CEMACS is located directly in the national park, there are countless mosquitoes and 4-5 lab cats (there are now 2 babies there again) as well as some animals that are both exciting and not – monkeys. Cute at first glance, but when you’re on your way to the cafeteria with food in your hand, it’s a bit of a mad rush: “Get to the cafeteria quickly before a monkey steals your food!” We have also had lab visits from monkeys, which were not to the delight of all parties. We differentiate between two types of monkeys: the good monkeys, aka Dusky leaf monkey or aka langur (Trachypithecus obscurus) vs. the bad monkeys, aka Macaque. The good monkeys are the monkeys with black fur that get scared when they see you and would never get too close. The bad monkeys – well, they are the bad monkeys who steal your food, spy on you and clean out laboratories.

But it’s not just monkeys that are part of our daily work at CEMACS. We also have to deal with visits from 2-metre-long lizards who want to explore the area or say a quick hello. But the lizards are less of a problem than the evil monkeys. You can find a funny picture below: Swimming lizards. When we approach the lizards, they quickly waddle away. And, of course, we also have some jellyfish right in front of the CEMACS. Not a problem if you don’t go swimming. However, Max is always looking for a quick cool down after work – although it’s 30 degrees in the water. That’s why Max always takes a bottle of vinegar with him – not to drink, but as a precaution against possible contact with jellyfish – and yes, the monkeys inspect the bottle at least 3-4 times every time they visit the beach until they realise that vinegar is not so enjoyable.

Ocean Acidification

What is the High Seas Treaty and Why Does It Matter?

You may have seen headlines recently about a new global treaty that went into effect just as news broke that the United States would be withdrawing from a number of other international agreements. It’s a confusing time in the world of environmental policy, and Ocean Conservancy is here to help make it clearer while, of course, continuing to protect our ocean.

What is the High Seas Treaty?

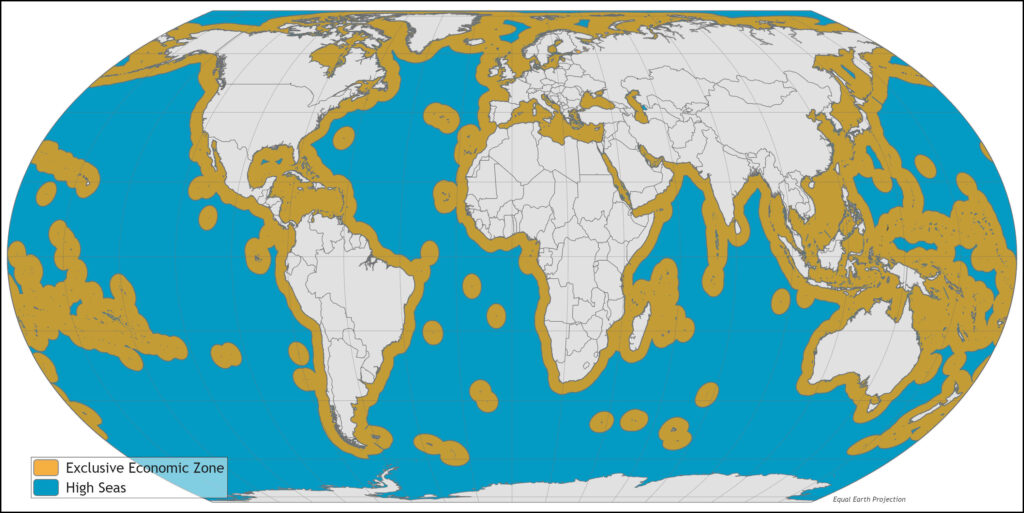

The “High Seas Treaty,” formally known as the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement, went into effect on January 17, 2026. We celebrated this win last fall, when the agreement reached the 60 ratifications required for its entry into force. (Since then, an additional 23 countries have joined!) It is the first comprehensive international legal framework dedicated to addressing the conservation and sustainable use of the high seas (the area of the ocean that lies 200 miles beyond the shorelines of individual countries).

To “ensure the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity” of these areas, the BBNJ addresses four core pillars of ocean governance:

- Marine genetic resources: The high seas contain genetic resources (genes of plants, animals and microbes) of great value for pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and food production. The treaty will ensure benefits accrued from the development of these resources are shared equitably amongst nations.

- Area-based management tools such as the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) in international waters. Protecting important areas of the ocean is essential for healthy and resilient ecosystems and marine biodiversity.

- Environmental impact assessments (EIA) will allow us to better understand the potential impacts of proposed activities that may harm the ocean so that they can be managed appropriately.

- Capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology with particular emphasis on supporting developing states. This section of the treaty is designed to ensure all nations benefit from the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity through, for example, the sharing of scientific information.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

Why is the High Seas Treaty Important?

The BBNJ agreement is legally binding for the countries that have ratified it and is the culmination of nearly two decades of negotiations. Its enactment is a historic milestone for global ocean governance and a significant advancement in the collective protection of marine ecosystems.

The high seas represent about two-thirds of the global ocean, and yet less than 10% of this area is currently protected. This has meant that the high seas have been vulnerable to unregulated or illegal fishing activities and unregulated waste disposal. Recognizing a major governance gap for nearly half of the planet, the agreement puts in place a legal framework to conserve biodiversity.

As it promotes strengthened international cooperation and accountability, the agreement will establish safeguards aimed at preventing and reversing ocean degradation and promoting ecosystem restoration. Furthermore, it will mobilize the international community to develop new legal, scientific, financial and compliance mechanisms, while reinforcing coordination among existing treaties, institutions and organizations to address long-standing governance gaps.

How is Ocean Conservancy Supporting the BBNJ Agreement?

Addressing the global biodiversity crisis is a key focal area for Ocean Conservancy, and the BBNJ agreement adds important new tools to the marine conservation toolbox and a global commitment to better protect the ocean.

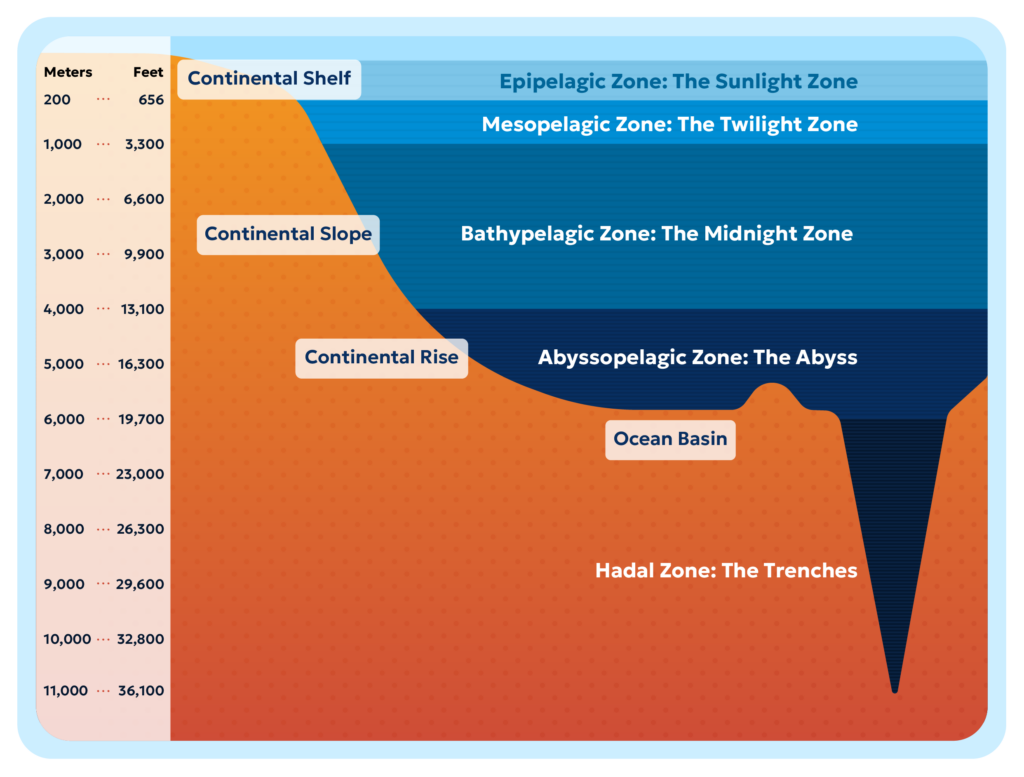

Ocean Conservancy’s efforts to protect the “ocean twilight zone”—an area of the ocean 200-1000m (600-3000 ft) below the surface—is a good example of why the BBNJ agreement is so important. The ocean twilight zone (also known as the mesopelagic zone) harbors incredible marine biodiversity, regulates the climate and supports the health of ocean ecosystems. By some estimates, more than 90% of the fish biomass in the ocean resides in the ocean twilight zone, attracting the interest of those eager to develop new sources of protein for use in aquaculture feed and pet foods.

Done poorly, such development could have major ramifications for the health of our planet, jeopardizing the critical role these species play in regulating the planet’s climate and sustaining commercially and ecologically significant marine species. Species such as tunas (the world’s most valuable fishery), swordfish, salmon, sharks and whales depend upon mesopelagic species as a source of food. Mesopelagic organisms would also be vulnerable to other proposed activities including deep-sea mining.

A significant portion of the ocean twilight zone is in the high seas, and science and policy experts have identified key gaps in ocean governance that make this area particularly vulnerable to future exploitation. The BBNJ agreement’s provisions to assess the impacts of new activities on the high seas before exploitation begins (via EIAs) as well as the ability to proactively protect this area can help ensure the important services the ocean twilight zone provides to our planet continue well into the future.

What’s Next?

Notably, the United States has not ratified the treaty, and, in fact, just a few days before it went into effect, the United States announced its withdrawal from several important international forums, including many focused on the environment. While we at Ocean Conservancy were disappointed by this announcement, there is no doubt that the work will continue.

With the agreement now in force, the first Conference of the Parties (COP1), also referred to as the BBNJ COP, will convene within the next year and will play a critical role in finalizing implementation, compliance and operational details under the agreement. Ocean Conservancy will work with partners to ensure implementation of the agreement is up to the challenge of the global biodiversity crisis.

The post What is the High Seas Treaty and Why Does It Matter? appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2026/02/25/high-seas-treaty/

Ocean Acidification

Hälsningar från Åland och Husö biological station

On Åland, the seasons change quickly and vividly. In summer, the nights never really grow dark as the sun hovers just below the horizon. Only a few months later, autumn creeps in and softly cloaks the island in darkness again. The rhythm of the seasons is mirrored by the biological station itself; researchers, professors, and students arrive and depart, bringing with them microscopes, incubators, mesocosms, and field gear to study the local flora and fauna peaking in the mid of summer.

This year’s GAME project is the final chapter of a series of studies on light pollution. Together, we, Pauline & Linus, are studying the effects of artificial light at night (ALAN) on epiphytic filamentous algae. Like the GAME site in Japan, Akkeshi, the biological station Husö here on Åland experiences very little light pollution, making it an ideal place to investigate this subject.

We started our journey at the end of April 2025, just as the islands were waking up from winter. The trees were still bare, the mornings frosty, and the streets quiet. Pauline, a Marine Biology Master’s student from the University of Algarve in Portugal, arrived first and was welcomed by Tony Cederberg, the station manager. Spending the first night alone on the station was unique before the bustle of the project began.

Linus, a Marine Biology Master’s student at Åbo Akademi University in Finland, joined the next day. Husö is the university’s field station and therefore Linus has been here for courses already. However, he was excited to spend a longer stretch at the station and to make the place feel like a second home.

Our first days were spent digging through cupboards and sheds, reusing old materials and tools from previous years, and preparing the frames used by GAME 2023. We chose Hamnsundet as our experimental site, (i.e. the same site that was used for GAME 2023), which is located at the northeast of Åland on the outer archipelago roughly 40 km from Husö. We got permission to deploy the experiments by the local coast guard station, which was perfect. The location is sheltered from strong winds, has electricity access, can be reached by car, and provides the salinity conditions needed for our macroalga, Fucus vesiculosus, to survive.

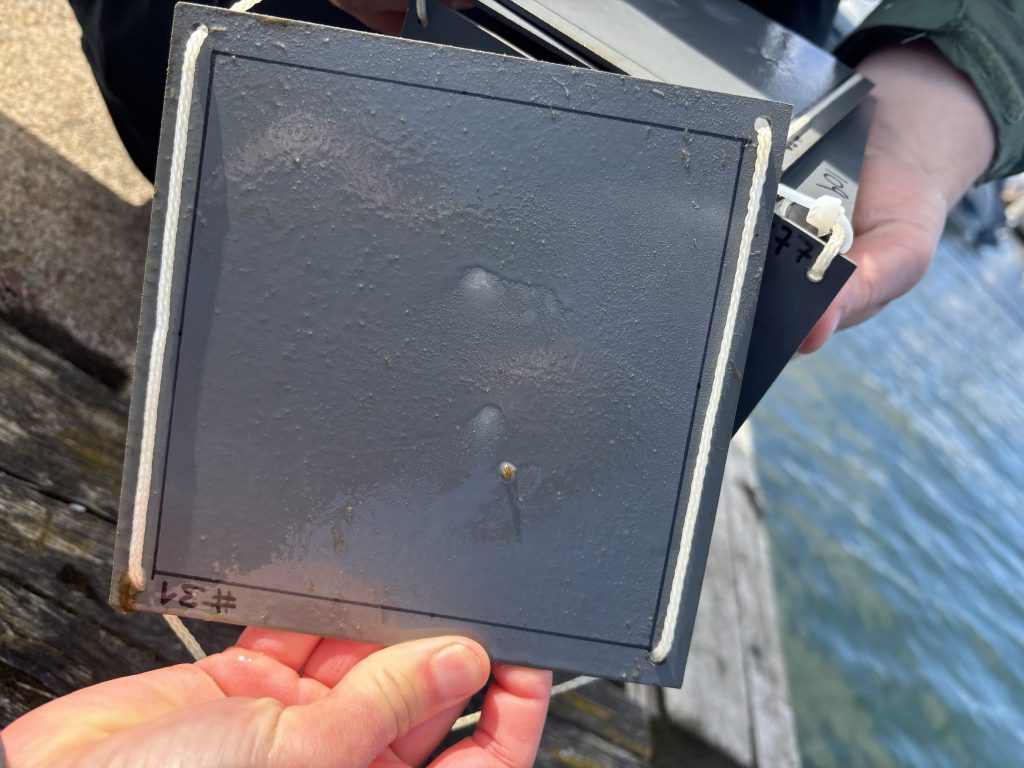

To assess the conditions at the experimental site, we deployed a first set of settlement panels in late April. At first, colonization was slow; only a faint biofilm appeared within two weeks. With the water temperature being still around 7 °C, we decided to give nature more time. Meanwhile, we collected Fucus individuals and practiced the cleaning and the standardizing of the algal thalli for the experiment. Scraping epiphytes off each thallus piece was fiddly, and agreeing on one method was crucial to make sure our results would be comparable to those of other GAME teams.

By early May, building the light setup was a project in itself. Sawing, drilling, testing LEDs, and learning how to secure a 5-meter wooden beam over the water. Our first version bent and twisted until the light pointed sideways instead of straight down onto the algae. Only after buying thicker beams and rebuilding the structure, we finally got a stable and functional setup that could withstand heavy rain and wind. The day we deployed our first experiment at Hamnsundet was cold and rainy but also very rewarding!

Outside of work, we made the most of the island life. We explored Åland by bike, kayak, rowboat, and hiking, visited Ramsholmen National Park during the ramson/ wild garlic bloom, and hiked in Geta with its impressive rock formations and went out boating and fishing in the archipelago. At the station on Husö, cooking became a social event: baking sourdough bread, turning rhubarb from the garden into pies, grilling and making all kind of mushroom dishes. These breaks, in the kitchen and in nature, helped us recharge for the long lab sessions to come.

Every two weeks, it was time to collect and process samples. Snorkeling to the frames, cutting the Fucus and the PVC plates from the lines, and transferring each piece into a freezer bag became our routine. Sampling one experiment took us 4 days and processing all the replicates in the lab easily filled an entire week. The filtering and scraping process was even more time-consuming than we had imagined. It turned out that epiphyte soup is quite thick and clogs filters fastly. This was frustrating at times, since it slowed us down massively.

Over the months, the general community in the water changed drastically. In June, water was still at 10 °C, Fucus carried only a thin layer of diatoms and some very persistent and hard too scrape brown algae (Elachista). In July, everything suddenly exploded: green algae, brown algae, diatoms, cyanobacteria, and tiny zooplankton clogged our filters. With a doubled filtering setup and 6 filtering units, we hoped to compensate for the additional growth.

However, what we had planned as “moderate lab days” turned into marathon sessions. In August, at nearly 20 °C, the Fucus was looking surprisingly clean, but on the PVC a clear winner had emerged. The panels were overrun with the green alga Ulva and looked like the lawn at an abandoned house. Here it was not enough to simply filter the solution, but bigger pieces had to be dried separately. In September, we concluded the last experiment with the help of Sarah from the Cape Verde team, as it was not possible for her to continue on São Vicente, the Cape Verdean island that was most affected by a tropical storm. Our final experiment brought yet another change into community now dominated by brown algae and diatoms. Thankfully our new recruit, sunny autumn weather, and mushroom picking on the side made the last push enjoyable.

By the end of summer, we had accomplished four full experiments. The days were sometimes exhausting but also incredibly rewarding. We learned not only about the ecological effects of artificial light at night, but also about the very practical side of marine research; planning, troubleshooting, and the patience it takes when filtering a few samples can occupy half a day.

Ocean Acidification

What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs?

Coral reefs are beautiful, vibrant ecosystems and a cornerstone of a healthy ocean. Often called the “rainforests of the sea,” they support an extraordinary diversity of marine life from fish and crustaceans to mollusks, sea turtles and more. Although reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean floor, they provide critical habitat for roughly 25% of all ocean species.

Coral reefs are also essential to human wellbeing. These structures reduce the force of waves before they reach shore, providing communities with vital protection from extreme weather such as hurricanes and cyclones. It is estimated that reefs safeguard hundreds of millions of people in more than 100 countries.

What is coral bleaching?

A key component of coral reefs are coral polyps—tiny soft bodied animals related to jellyfish and anemones. What we think of as coral reefs are actually colonies of hundreds to thousands of individual polyps. In hard corals, these tiny animals produce a rigid skeleton made of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). The calcium carbonate provides a hard outer structure that protects the soft parts of the coral. These hard corals are the primary building blocks of coral reefs, unlike their soft coral relatives that don’t secrete any calcium carbonate.

Coral reefs get their bright colors from tiny algae called zooxanthellae. The coral polyps themselves are transparent, and they depend on zooxanthellae for food. In return, the coral polyp provides the zooxanethellae with shelter and protection, a symbiotic relationship that keeps the greater reefs healthy and thriving.

When corals experience stress, like pollution and ocean warming, they can expel their zooxanthellae. Without the zooxanthellae, corals lose their color and turn white, a process known as coral bleaching. If bleaching continues for too long, the coral reef can starve and die.

Ocean warming and coral bleaching

Human-driven stressors, especially ocean warming, threaten the long-term survival of coral reefs. An alarming 77% of the world’s reef areas are already affected by bleaching-level heat stress.

The Great Barrier Reef is a stark example of the catastrophic impacts of coral bleaching. The Great Barrier Reef is made up of 3,000 reefs and is home to thousands of species of marine life. In 2025, the Great Barrier Reef experienced its sixth mass bleaching since 2016. It should also be noted that coral bleaching events are a new thing because of ocean warming, with the first documented in 1998.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

How you can help

The planet is changing rapidly, and the stakes have never been higher. The ocean has absorbed roughly 90% of the excess heat caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, and the consequences, including coral die-offs, are already visible. With just 2℃ of planetary warming, global coral reef losses are estimated to be up to 99% — and without significant change, the world is on track for 2.8°C of warming by century’s end.

To stop coral bleaching, we need to address the climate crisis head on. A recent study from Scripps Institution of Oceanography was the first of its kind to include damage to ocean ecosystems into the economic cost of climate change – resulting in nearly a doubling in the social cost of carbon. This is the first time the ocean was considered in terms of economic harm caused by greenhouse gas emissions, despite the widespread degradation to ocean ecosystems like coral reefs and the millions of people impacted globally.

This is why Ocean Conservancy advocates for phasing out harmful offshore oil and gas and transitioning to clean ocean energy. In this endeavor, Ocean Conservancy also leads international efforts to eliminate emissions from the global shipping industry—responsible for roughly 1 billion tons of carbon dioxide every year.

But we cannot do this work without your help. We need leaders at every level to recognize that the ocean must be part of the solution to the climate crisis. Reach out to your elected officials and demand ocean-climate action now.

The post What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs? appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs?

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits