The solar lantern is a revolutionary piece of technology.

Operating with a small in-built solar panel, connected to a battery and using an LED light bulb, it can transform how rural communities see the world.

Its use in places without access to mains electricity has taken off in the past 15 years, alongside the wider growth in solar power around the world.

An estimated 600 million people in sub-Saharan Africa still live without reliable access to electricity, according to the World Bank. The introduction of solar power – coupled with energy-efficient lighting – is key in tackling this problem.

Many villages not served by national grids are forced to use kerosene lamps and candles, or burn straw in the evening, which is costly and dangerous to human health. London-based think-tank ODI Global estimates that low-income households in Africa spend US$6.5 billion a year on such inefficient lighting options.

Solar power changes the equation, allowing streets to be lit, children to study at night, and a sense of security to exist. Greater electricity access enables farmers to work an extended day and use solar-powered irrigation and cooling systems to grow and process their crops.

African leaders seek investments in ailing grid infrastructure to achieve energy goals

“Reliable and affordable energy creates economic transformation,” said Eva Roig, a spokesperson for GOGLA, an Amsterdam-based trade body for the off-grid solar energy industry. The organisation estimates that US$9 billion in additional income has already been created by businesses as a result of switching to solar in place of fossil fuel alternatives.

“In off-grid locations, lack of energy restrains farmers from higher productivity and, with a growing young population, offers few employment opportunities or possibilities to create new businesses,” she added.

The challenge for off-grid solar power is to reach the hundreds of millions of people in need and create a stable market for its continuance.

Electric power key to tackling poverty

UK charity SolarAid was founded in 2006 with the aim of creating a world “where everyone has access to clean, renewable energy” and eradicating the use of kerosene lamps in Africa.

A couple of years later it set up SunnyMoney, a social enterprise which uses a community distribution model to raise awareness and increase demand for solar power. Local teachers explain how the technology works and independent agents sell the products. SunnyMoney supports them with logistics, training and engagement along the way.

“We believe that access to electricity is fundamental in the fight against poverty. Access to solar lighting and power means that families are saving money, extending productive hours, increasing access to study hours and also increasing safety,” explained John Keane, CEO at SolarAid, based in Zambia.

The charity has reportedly helped 12 million people through the social enterprise, with projects in Senegal, Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya, Zambia and Malawi.

While models such as SunnyMoney can stoke the solar market, larger businesses need to step in and supply the kit itself. D.light is one of the solar companies that has done more than most to bring affordable solar power to some of the remotest villages in Africa.

Finance for renewable energy in sub-Saharan Africa is defying the odds

The US company is deeply embedded across the continent, with a vision to make solar products accessible to low-income families. The business had one of its most successful years in 2024, and says it reached 24 million people with solar systems last year alone.

But it hasn’t always been plain sailing. “I don’t think we realised how difficult it would be to commercialise and scale off-grid solar products,” d.light’s founder and CEO, Nedjip Tozun, commented in an interview last year.

While its products now power around 32 million homes, building that capacity took time, patience and good fortune. Tozun explained that during the early years in the mid 2000s the difficulties lay in building a high-quality product which could be distributed to remote areas and with financing to enable people to pay for it. The company was forced to create those capabilities in-house in order to scale and overcome external barriers.

Funding energy efficiency to expand use

Improving energy efficiency is one such challenge the off-grid industry has sought to solve. Solar devices need to hold the sun’s energy long enough to be used for a wide range of purposes. This is where LED lighting comes in.

“Over the past 10 years, the growing availability of increasingly energy-efficient appliances, such as LED lighting is transforming what’s possible,” said Keane. “It’s the foundation for designing inclusive solutions that deliver long-term impact.”

The main benefits, he explained, is that LED lighting drastically reduces the amount of electricity needed to light homes, enabling households on lower incomes to meet their essential needs with small solar systems.

As off-grid solar kits are small by design, using the power with efficient lighting or low-voltage appliances, such as refrigerators, means the energy goes further and is matched to the user’s needs.

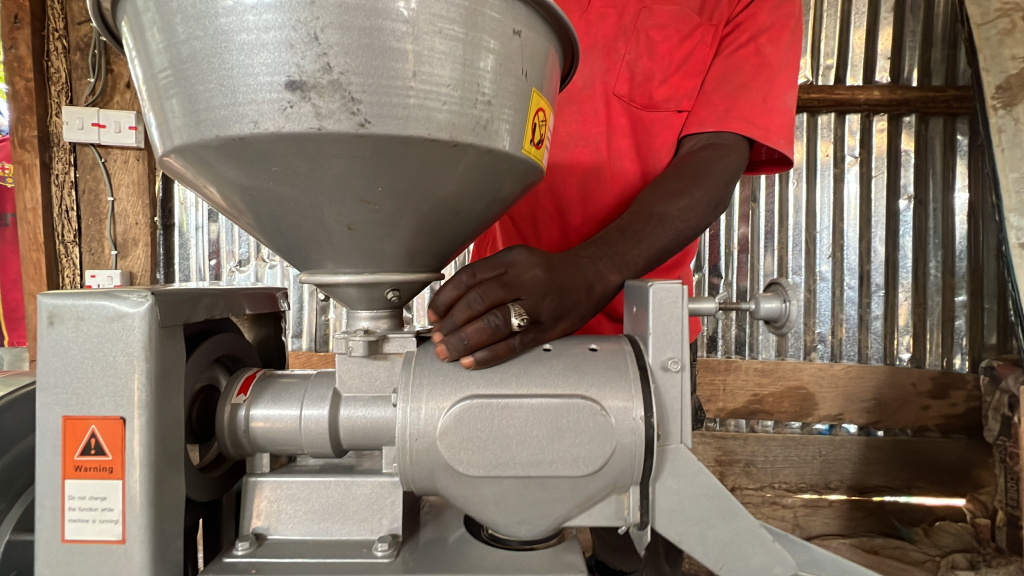

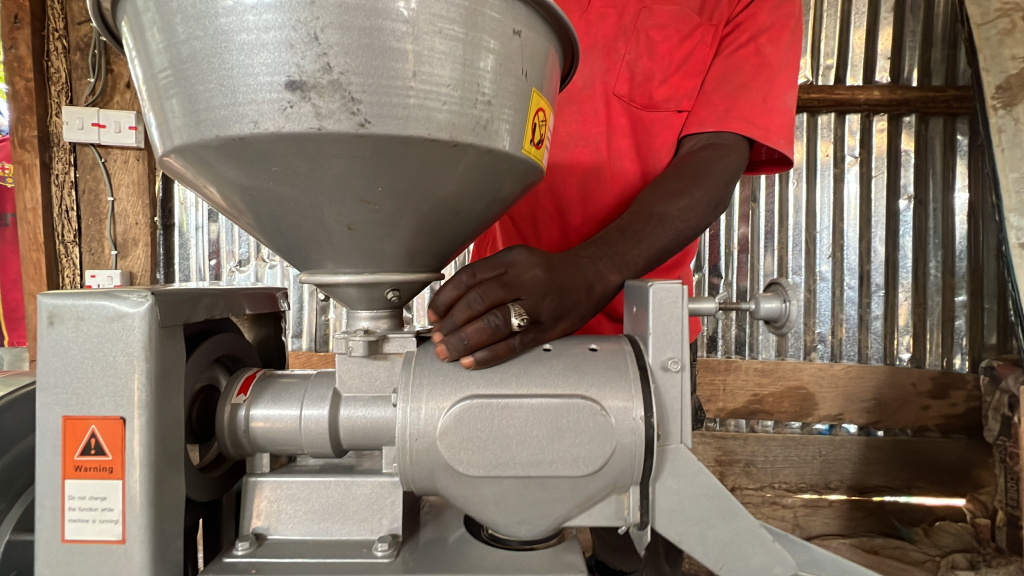

Pairing solar with technologies to support economic activity, so-called “productive use”, is a growing area within the industry. Solar can be applied in a range of commercial settings, and on any number of appliances, from sewing machines to water pumps, or from seed pressers to ceiling fans. But to do so effectively those appliances need to be energy-efficient and upgrading is expensive.

New financing initiatives such as PUFF – the Productive Use Financing Facility – are playing a role by offering subsidies to suppliers to help bring down the costs for farmers and businesses. After a successful pilot, the scheme was recently extended with an additional US$6.1 million to support access to 10,000 “high-impact” appliances, according to CLASP, a non-profit which started the initiative.

“Efficient appliances and equipment turn energy into opportunity and should be considered essential energy infrastructure, alongside renewables,” commented Emmanuel Aziebor, a senior director at CLASP, in a media statement.

Financial barriers to adoption

Overall, the coming together of small solar technology, LED lighting and socially minded businesses has grown the market significantly over the past decade.

In Kenya, off-grid solar now accounts for an estimated 75% of rural electricity access. The country has a target to reach universal access by 2030 and solar plays a big part in the government’s plans.

But the same barriers to scaling the market remain. Despite the success of using mobile technology and pay-as-you-go models to spread out costs for the consumer, affordable solar products are still out of reach for many. Research from ESMAP, an energy programme run by the World Bank, found that only 22% of households that lack electricity globally could afford the monthly payment to access a basic solar lantern and home system able to provide power for at least four hours a day.

“Governments should fully integrate off-grid solar into their national energy plans and programmes,” said Roig of GOGLA, adding that incentives such as tax breaks, subsidies and public-private partnerships are needed to reach the poorest households.

Making solar affordable for all

One way to bring down costs for consumers is to de-risk investments for solar power producers. The Beyond Grid for Zambia pilot project sought to do exactly that by providing financing to companies on a per-connection basis.

The project, which ran from 2016 to 2022, also worked with the Zambian government to smooth market access, such as providing a VAT exemption for LED lights. The successful results – with over 194,000 households fitted with off-grid solar – have led to ambitious plans to scale the project across the whole African continent.

The remoteness of many villages makes repairing and maintaining solar kits another challenge. Collecting, servicing and replacing these products can be expensive for companies. Research from SolarAid suggests that while manufacturers agree that repair work needs to improve, it remains an ambition for many.

Among the possible solutions include extending warranty times, providing technical training in-country, and greater guidance on how to conduct repairs at the community level. SunnyMoney already provides technicians with its own mobile repair app, which could be expanded and used as a template for manufacturers.

Despite the challenges, the work to reach tens of millions of remote households is being reinforced and stepped up. SolarAid is midway through a pilot project to connect TA Kasakula, a village in rural Malawi where almost all residents live in extreme poverty. The project is trialling a new financing model which eliminates upfront costs, with customers only paying for the electricity they use.

The stories coming back to the social enterprise are of revelation and changed lives. “When we switched on the lights, some children were dancing, jumping,” reported Goodwill Kongalwa. “Then everyone rushed to where there were books because they saw they had a chance to study at home.”

Adam Wentworth is a freelance writer based in Brighton, UK.

The post How off-grid solar is beating the odds to transform lives in rural Africa appeared first on Climate Home News.

How off-grid solar is beating the odds to transform lives in rural Africa

Climate Change

A Tiny Caribbean Island Sued the Netherlands Over Climate Change, and Won

The case shows that climate change is a fundamental human rights violation—and the victory of Bonaire, a Dutch territory, could open the door for similar lawsuits globally.

From our collaborating partner Living on Earth, public radio’s environmental news magazine, an interview by Paloma Beltran with Greenpeace Netherlands campaigner Eefje de Kroon.

A Tiny Caribbean Island Sued the Netherlands Over Climate Change, and Won

Climate Change

Greenpeace organisations to appeal USD $345 million court judgment in Energy Transfer’s intimidation lawsuit

SYDNEY, Saturday 28 February 2026 — Greenpeace International and Greenpeace organisations in the US announce they will seek a new trial and, if necessary, appeal the decision with the North Dakota Supreme Court following a North Dakota District Court judgment today awarding Energy Transfer (ET) USD $345 million.

ET’s SLAPP suit remains a blatant attempt to silence free speech, erase Indigenous leadership of the Standing Rock movement, and punish solidarity with peaceful resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Greenpeace International will also continue to seek damages for ET’s bullying lawsuits under EU anti-SLAPP legislation in the Netherlands.

Mads Christensen, Greenpeace International Executive Director said: “Energy Transfer’s attempts to silence us are failing. Greenpeace International will continue to resist intimidation tactics. We will not be silenced. We will only get louder, joining our voices to those of our allies all around the world against the corporate polluters and billionaire oligarchs who prioritise profits over people and the planet.

“With hard-won freedoms under threat and the climate crisis accelerating, the stakes of this legal fight couldn’t be higher. Through appeals in the US and Greenpeace International’s groundbreaking anti-SLAPP case in the Netherlands, we are exploring every option to hold Energy Transfer accountable for multiple abusive lawsuits and show all power-hungry bullies that their attacks will only result in a stronger people-powered movement.”

The Court’s final judgment today rejects some of the jury verdict delivered in March 2025, but still awards hundreds of millions of dollars to ET without a sound basis in law. The Greenpeace defendants will continue to press their arguments that the US Constitution does not allow liability here, that ET did not present evidence to support its claims, that the Court admitted inflammatory and irrelevant evidence at trial and excluded other evidence supporting the defense, and that the jury pool in Mandan could not be impartial.[1][2]

ET’s back-to-back lawsuits against Greenpeace International and the US organisations Greenpeace USA (Greenpeace Inc.) and Greenpeace Fund are clear-cut examples of SLAPPs — lawsuits attempting to bury nonprofits and activists in legal fees, push them towards bankruptcy and ultimately silence dissent.[3] Greenpeace International, which is based in the Netherlands, is pursuing justice in Europe, with a suit against ET under Dutch law and the European Union’s new anti-SLAPP directive, a landmark test of the new legislation which could help set a powerful precedent against corporate bullying.[4]

Kate Smolski, Program Director at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, said: “This is part of a worrying trend globally: fossil fuel corporations are increasingly using litigation to attack and silence ordinary people and groups using the law to challenge their polluting operations — and we’re not immune to these tactics here in Australia.

“Rulings like this have a chilling effect on democracy and public interest litigation — we must unite against these silencing tactics as bad for Australians and bad for our democracy. Our movement is stronger than any corporate bully, and grows even stronger when under attack.”

Energy Transfer’s SLAPPs are part of a wave of abusive lawsuits filed by Big Oil companies like Shell, Total, and ENI against Greenpeace entities in recent years.[3] A couple of these cases have been successfully stopped in their tracks. This includes Greenpeace France successfully defeating TotalEnergies’ SLAPP on 28 March 2024, and Greenpeace UK and Greenpeace International forcing Shell to back down from its SLAPP on 10 December 2024.

-ENDS-

Images available in Greenpeace Media Library

Notes:

[1] The judgment entered by North Dakota District Court Judge Gion follows a jury verdict finding Greenpeace entities liable for more than US$660 million on March 19, 2025. Judge Gion subsequently threw out several items from the jury’s verdict, reducing the total damages to approximately US$345 million.

[2] Public statements from the independent Trial Monitoring Committee

[3] Energy Transfer’s first lawsuit was filed in federal court in 2017 under the RICO Act – the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a US federal statute designed to prosecute mob activity. The case was dismissed in 2019, with the judge stating the evidence fell “far short” of what was needed to establish a RICO enterprise. The federal court did not decide on Energy Transfer’s claims based on state law, so Energy Transfer promptly filed a new case in a North Dakota state court with these and other state law claims.

[4] Greenpeace International sent a Notice of Liability to Energy Transfer on 23 July 2024, informing the pipeline giant of Greenpeace International’s intention to bring an anti-SLAPP lawsuit against the company in a Dutch Court. After Energy Transfer declined to accept liability on multiple occasions (September 2024, December 2024), Greenpeace International initiated the first test of the European Union’s anti-SLAPP Directive on 11 February 2025 by filing a lawsuit in Dutch court against Energy Transfer. The case was officially registered in the docket of the Court of Amsterdam on 2 July, 2025. Greenpeace International seeks to recover all damages and costs it has suffered as a result of Energy Transfers’s back-to-back, abusive lawsuits demanding hundreds of millions of dollars from Greenpeace International and the Greenpeace organisations in the US. The next hearing in the Court of Amsterdam is scheduled for 16 April, 2026.

Media contact:

Kate O’Callaghan on 0406 231 892 or kate.ocallaghan@greenpeace.org

Climate Change

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

The Trump administration’s relentless rollback of public health and environmental protections has allowed widespread toxic exposures to flourish, warn experts who helped implement safeguards now under assault.

In a new report that outlines a dozen high-risk pollutants given new life thanks to weakened, delayed or rescinded regulations, the Environmental Protection Network, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group of hundreds of former Environmental Protection Agency staff, warns that the EPA under President Donald Trump has abandoned the agency’s core mission of protecting people and the environment from preventable toxic exposures.

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits