Wider adoption of heat pumps could accelerate decarbonisation of heating in China’s carbon-intensive buildings and light industry sectors, a report by the International Energy Agency (IEA) says.

The report, published in collaboration with Tsinghua University, finds that, by using heat pumps as part of China’s strategy to reach carbon neutrality by 2060, direct emissions for heating in buildings could fall by 75% to 70m tonnes of carbon dioxide (MtCO2) in 2050, due to increased electrification and improvements to energy efficiency.

Similarly, using heat pumps could help reduce direct emissions from heating in light industries from more than 110MtCO2 today to less than 10MtCO2 in 2050.

In 2023, China was one of the few nations to see total heat pump sales rise. However, greater policy support is still needed to accelerate uptake and help shift the buildings and light industry sectors towards less-carbon intensive energy sources, the report says.

- How much energy does China consume for heat?

- How can heat pumps help China meet its ‘dual carbon’ goals?

- How effective are heat pumps as a solution for China?

- How can policy support heat pump adoption?

How much energy does China consume for heat?

China’s final energy consumption was 107 exajoules (EJ) of energy in 2022. Within this, the IEA report says, heat consumption reached about 50EJ. China’s heat consumption equals “about one-third” of total heat consumption globally.

Around a quarter of China’s heat use is in buildings, with the remainder in industry.

In the buildings sector, heat consumption has grown faster in China than in any other country over the past decade, standing at 12EJ in 2022. This is largely due to growing demand for heat for space and water, which has “nearly tripled” direct and indirect emissions since 2000.

Since 2010, direct coal consumption for heating overall has fallen by 15%. The IEA report attributes this to policy drives beginning in the mid-2010s, initially “to improve air quality, then later to expand clean and low-carbon heating”.

However, an exception to this is district heating, namely, a centralised heating mechanism that is the dominant source of heat for urban areas in northern China. Heat pumps and other decentralised solutions are more common in southern and rural northern China.

District heating networks in northern China rely on coal for more than 80% of their heat production. It is the key driver of coal consumption in building heat provision across the country, according to the IEA.

One 2019 study found that China’s emissions from district heating alone were greater than the total CO2 emissions of the UK.

Dr Chiara Delmastro and Dr Rafael Martinez Gordon, the report’s lead authors, tell Carbon Brief:

“[This] was mostly driven by the expansion of [heat] networks in north urban China, in particular…The length of the district heat network has increased by 250% since 2010, of which the large majority is in the north.”

Delmastro and Martinez Gordon also note, however, that “China has taken action towards cleaner and more efficient heating in recent years” – for example, by shifting from using coal-fired boilers to more efficient combined heat and power plants.

Meanwhile, heat consumption for industry in 2022 totalled 38EJ. Some of this demand is for low- and medium-temperature heat (below 200C), which is generally required for light industries, as well as the pulp and paper sector and some chemical sector processes.

This demand – which could easily be served by existing state-of-the-art heat pump technology – totaled 4.7EJ in 2022 and released more than 110MtCO2 of direct emissions, the report says.

However, more than 80% of industrial demand for heat requires temperatures above 200C, predominantly for iron and steel manufacturing. Other industries that require such high temperatures include non-metallic minerals and non-ferrous metals, as well as some processes in the chemicals and petrochemicals and pulp and paper sectors. These sectors comprised the majority of industrial heat demand, consuming 33EJ in 2022.

How can heat pumps help China meet its ‘dual carbon’ goals?

Heat demand in buildings and industry in China is largely driven by coal and accounts for 40% of both China’s coal consumption and its CO2 emissions.

The IEA does note, however, that the use of coal for heat has reduced slightly, largely due to “policies to improve air quality, reduce CO2 emissions and maximise energy efficiency”.

In 2022, carbon emissions from space and water heating accounted for the vast majority of direct emissions from buildings in China, around 290MtCO2, while direct emissions from heating for light industry totalled 110MtCO2. The IEA places China’s total carbon emissions at 12,135MtCO2 in 2022.

The report provides estimates of the uptake of heat pumps in China under the “announced pledges scenario” (APS), in which governments are given the benefit of the doubt and assumed to meet all of their climate goals on time and in full.

It also looks at uptake under the “stated policies scenario” (STEPS), reflecting the IEA’s own judgement of where government policy is currently heading.

If China upholds its “dual carbon” commitments, in line with the APS, then the IEA estimates that heat pump capacity in buildings would rise to 1,400 gigawatts (GW) in 2050, meeting one-quarter of China’s heat demand for the sector.

Under the APS, China would install 100GW in buildings each year until 2050 – the equivalent of “the capacity deployed in the US, China and the EU in 2022 combined”.

Emissions from buildings heat would fall from 290MtCO2 to 80MtCO2 in 2050, a reduction of 210MtCO2, with heat pumps accounting for 30% of this decrease. The other drivers for building decarbonisation would include greater adoption of electrification, energy efficiency measures and behaviour changes.

For light industry, under the APS, approximately 1.5GW of heat pumps would be installed annually between 2025 and 2050, meeting one-fifth of heat demand in 2050.

This would contribute to “drastically” reducing carbon emissions, which would fall by 95% overall from more than 110MtCO2 to 10MtCO2. Electrification, including through use of heat pumps, would be responsible for 70% of these emissions reductions.

The report adds that two energy-intensive sectors could be well-suited to using heat pumps: the pulp and paper sector, in which around 55% of current heat demand could be provided by industrial heat pumps, and the chemical sector, for which around 18% of demand could be met.

Heat pumps would be unlikely to serve demand for other energy-intensive sectors, however, as “only a few early-stage prototypes exist for temperatures beyond 200C, all of which are far from being ready for the mass market”.

Even under the STEPS, the stock of heat pumps in buildings in China would double, reaching more than 1,100GW by 2050 and contributing to building emissions falling by more than 25%, with fuel-switching options such as coal-to-gas also playing a role.

For light industries, heat pump-led CO2 emissions reductions under STEPs would “remain limited”, as under the current policy settings, heat pumps may be “deployed slowly”. Overall, by 2050 heat-related emissions would only fall by 15%.

Significantly, the policies required to meet climate goals in China – and the rest of the world – under the APS would see some industries “strongly mobilised”, the report says. Sectors such as mining and machinery would need to expand, ramping up clean-energy technology production to meet domestic and global demand.

While this additional industrial activity would raise China’s heat demand by 5% in the APS compared with the STEPS, the associated emissions would be more than offset by the savings enabled by wider deployment of electrification and clean heating technologies.

Moreover, the deployment of heat pumps would allow for a 20% decline in the energy intensity of heat supply by 2050 – the energy demand per unit of heat – compared to today, the report says.

The alignment between expanded heat pump use and decarbonisation of the electricity system could see indirect emissions from power generation for heat drop by more than 40% by 2030 as more renewable and nuclear power comes online, it adds. By 2050, electricity’s share in heat generation could exceed 75%.

For example, the IEA states that the pulp and paper sector could see coal use “almost entirely phased out by 2050”, if China’s climate goals are met. The sector has already cut the share of coal in its energy needs from 43% in 2010 to 10% in 2022, due to electrification and coal-to-gas shifts.

Under the APS, direct coal use for space and water heating in China would fall by 75% by 2030 and would be “almost completely phased out” by 2040, with heat pumps becoming a key technology for heating in urban and rural areas by 2050.

However, significant investment would be needed in this scenario to deploy enough heat pumps to meet demand.

How effective are heat pumps as a solution for China?

With more than 250GW of installed heat pump capacity in buildings in 2023, China accounts for more than 25% of global heat pump sales and was the only major market to see heat pump sales grow in 2023, the report says. In 2022, 8% of all heating equipment sales for buildings in China were heat pumps.

They are “already the norm” for space heating and cooling in buildings in some parts of central and southern China, which do not benefit from centralised district heating. Rural areas are now seeing a growing uptake of heat pumps, due to policy support to encourage rural regions to limit coal consumption, the report adds.

The same is also true for district heating, where network operators are increasingly installing heat pumps. While the majority are “air-source” pumps operating at relatively low temperatures, some networks are beginning to use large-scale heat pumps that recycle waste heat from steel mills, sewage treatment processes and coal chemical plants.

They “offer one of the most efficient options for decarbonising heat in district heating networks, buildings and industry”, according to the report.

In terms of both direct and indirect emissions, annual carbon emissions from a heat pump currently installed in China are more than 30% lower than those from gas boilers. “Shifting from fossil fuel boilers to heat pumps”, the report says, “would reduce CO2 emissions virtually everywhere they are installed”.

Despite high upfront installation costs, heat pumps also help users save money on energy bills over their lifetimes, according to the IEA.

The image below shows the different climate zones across China. Air-to-air heat pumps are more cost-effective than both gas boilers and electric heaters in some colder climates, as well as in regions with hot summers and cold winters.

Air-to-water heat pumps save money over electric heaters, although they are only less expensive than gas boilers in areas with competitive electricity prices compared to gas.

Heat pump use in energy-intensive industries is less viable, as current technologies to generate temperatures above 200C are still largely under development.

However, for light industries, industrial heat pumps are “far cheaper” than gas and electric boilers and nearly cost-competitive with coal boilers over their lifetimes, due to their high efficiency levels, states the report.

Despite this, uptake is not widespread, due to high upfront installation costs and lack of public awareness of the effectiveness of heat pumps.

Delmastro and Martinez Gordon tell Carbon Brief:

“In certain processes alternative technologies [to heat pumps] might be less costly and more appropriate, and – depending on policy decisions – different levels of heat pump deployment may be stimulated. However, to meet China’s carbon neutrality goal, we estimate that heat pumps need to supply at least 20% of heat demand in light industries by 2050.”

The report adds that state-of-the-art heat pumps – heat pump technology that is either newly-released or close to release – are well-placed to meet heat consumption needs in the building sectors and light industry sectors, and could theoretically supply about 40% of demand.

In addition, China currently wastes heat resources that could be redirected via heat pumps. In 2021, it generated 45EJ of waste heat resources – almost equal to the combined heating demand of buildings and industry – from sources such as nuclear power plants, other power plants, industrial activity, data centres and wastewater, according to the report.

How can policy support heat pump adoption?

Heat pumps have “increasingly featured” in China’s national-level energy and climate policy as one aspect of the energy transition. For instance, the 14th “five-year plan” for a modern energy system (2021-2025) calls for the expansion of clean heating provision for end-users as part of its electrification drive.

However, Delmastro and Martinez Gordon explain that the more targeted, practical policy recommendations in the IEA report “should [fall] under the umbrella of a clear national action plan for heating decarbonisation, which is missing now in China”.

This would allow China to set quantitative targets for heat pump use that would provide a clear signal to markets and promote wider investment in R&D, manufacturing and deployment.

Meanwhile, the report suggests that more stringent performance requirements for new buildings, stronger energy performance benchmarks, inclusion of heat pump installation requirements in building codes and extension of the scope of the national emissions trading scheme (ETS) to include industry could all drive heat pump adoption.

Loans, tax credits and other financial support mechanisms could address consumer reluctance to pay high upfront installation costs, adds the report.

The northern city of Tianjin offered grants of 25,000 yuan ($3,700) for air-source heat pump purchases, but this is not a common practice – particularly in urban regions.

Raising awareness of the benefits of industrial heat pumps and reducing electricity costs for industry could accelerate uptake in light industry, the report says.

Electricity pricing incentives have already seen rural residential areas switch from using coal to using gas for heating. Similar incentives for electricity in rural parts of Beijing, as well as subsidies for installing heat pumps, mean that heat pumps are now the cheapest heating option for households in that region, based on IEA calculations.

Expanding this policy nationwide could “further increase the competitiveness of heat pumps in regions where electricity currently costs significantly more than gas”, the report states.

Other measures that could make heat pumps more attractive to consumers include combining heat pumps with solar panels or solar thermal solutions, plus adapting the power system to provide tiered electricity pricing and time-of-use power market measures.

Finally, more recovery of waste energy resources, combined with thermal energy storage technologies, could “optimise heat supply by transforming surplus electricity…into heat and storing it for use during the winter heating”, the report says.

“In northern Hebei, for example”, it adds, “heat recovered by heat pumps from renewable power and waste heat could account for 80% of the district heat supply during winter in 2050”.

The post Heat pumps could help cut China’s building CO2 emissions by 75%, says IEA appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heat pumps could help cut China’s building CO2 emissions by 75%, says IEA

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: World’s biggest historic polluter – the US – is pulling out of UN climate treaty

The US, which has announced plans to withdraw from the global climate treaty – the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – is more historically responsible for climate change than any other country or group.

Carbon Brief analysis shows that the US has emitted a total of 542bn tonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2) since 1850, by burning fossil fuels, cutting down trees and other activities.

This is the largest contribution to the Earth’s warming climate by far, as shown in the figure below, with China’s 336GtCO2 significantly behind in second and Russia in third at 185GtCO2.

The US is responsible for more than a fifth of the 2,651GtCO2 that humans have pumped into the atmosphere between 1850 and 2025 as a result of fossil fuels, cement and land-use change.

China is responsible for another 13%, with the 27 nations of the EU making up another 12%.

In total, these cumulative emissions have used up more than 95% of the carbon budget for limiting global warming to 1.5C and are the predominant reason the Earth is already nearly 1.5C hotter than in pre-industrial times.

The US share of global warming is even more disproportionate when considering that its population of around 350 million people makes up just 4% of the global total.

On the basis of current populations, the US’s per-capita cumulative historical emissions are around 7 times higher than those for China, more than double the EU’s and 25 times those for India.

The US’s historical emissions of 542GtCO2 are larger than the combined total of the 133 countries with the lowest cumulative contributions, a list that includes Saudi Arabia, Spain and Nigeria. Collectively, these 133 countries have a population of more than 3 billion people.

See Carbon Brief’s previous detailed analysis of historical responsibility for climate change for more details on the data sources and methodology, as well as consumption-based emissions.

Additionally, in 2023, Carbon Brief published an article that looked at the “radical” impact of reassigning responsibility for historical emissions to colonial rulers in the past.

This approach has a very limited impact on the US, which became independent before the vast majority of its historical emissions had taken place.

The post Analysis: World’s biggest historic polluter – the US – is pulling out of UN climate treaty appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: World’s biggest historic polluter – the US – is pulling out of UN climate treaty

Greenhouse Gases

Our strategy for 2026 and beyond

Our strategy for 2026 and beyond

During his Fall Conference opening remarks last fall, CCL Executive Director Ricky Bradley outlined the next chapter of CCL’s work — one that is firmly rooted in our values, but guided by a sharper strategy. Now that 2026 is getting underway, we’re entering that next chapter in earnest.

“Today’s political landscape, and our country, desperately needs our respectful approach and our bridge-building ethos — and the climate needs our efforts to be more effective than ever,” Ricky said in November.

“Over the past few months, CCL’s leadership team and I have been hard at work on a strategic planning process to achieve that. We’ve drilled down on everything, getting clear about CCL’s mission, our contributions to the overall goal of solving climate change, and the training and programs necessary to get us there.”

“Over the past few months, CCL’s leadership team and I have been hard at work on a strategic planning process to achieve that. We’ve drilled down on everything, getting clear about CCL’s mission, our contributions to the overall goal of solving climate change, and the training and programs necessary to get us there.”

Our work identified three elements that we think are crucial to advancing climate solutions in Congress. For members of Congress to pass climate policy, they need to see climate as a salient issue — in other words, they need to think it matters to people, including the people they listen to most. They need to see climate action as feasible. And engaging on the issue needs to be politically safe. Satisfying these conditions is how we’re going to achieve the legislative action necessary to solve climate change.

Part of getting there is making sure that our volunteers have the skills they need to transcend partisanship, build trust across divides, and forge the relationships and alliances that lead to enduring climate action. Enter: Our new BRIDGE Advocacy Program. Launching this weekend during our January Monthly Meeting, this robust new program will strengthen your communication skills and deepen your relationships with congressional offices in the year ahead.

All of this and more is outlined in CCL’s 2026 Strategic Plan document. Dive into the strategic plan to see CCL’s objectives for the new year and beyond, and learn more on Saturday during our first monthly meeting of 2026. We can’t wait to enter this next chapter with you!

The post Our strategy for 2026 and beyond appeared first on Citizens' Climate Lobby.

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: UK renewables enjoy record year in 2025 – but gas power still rises

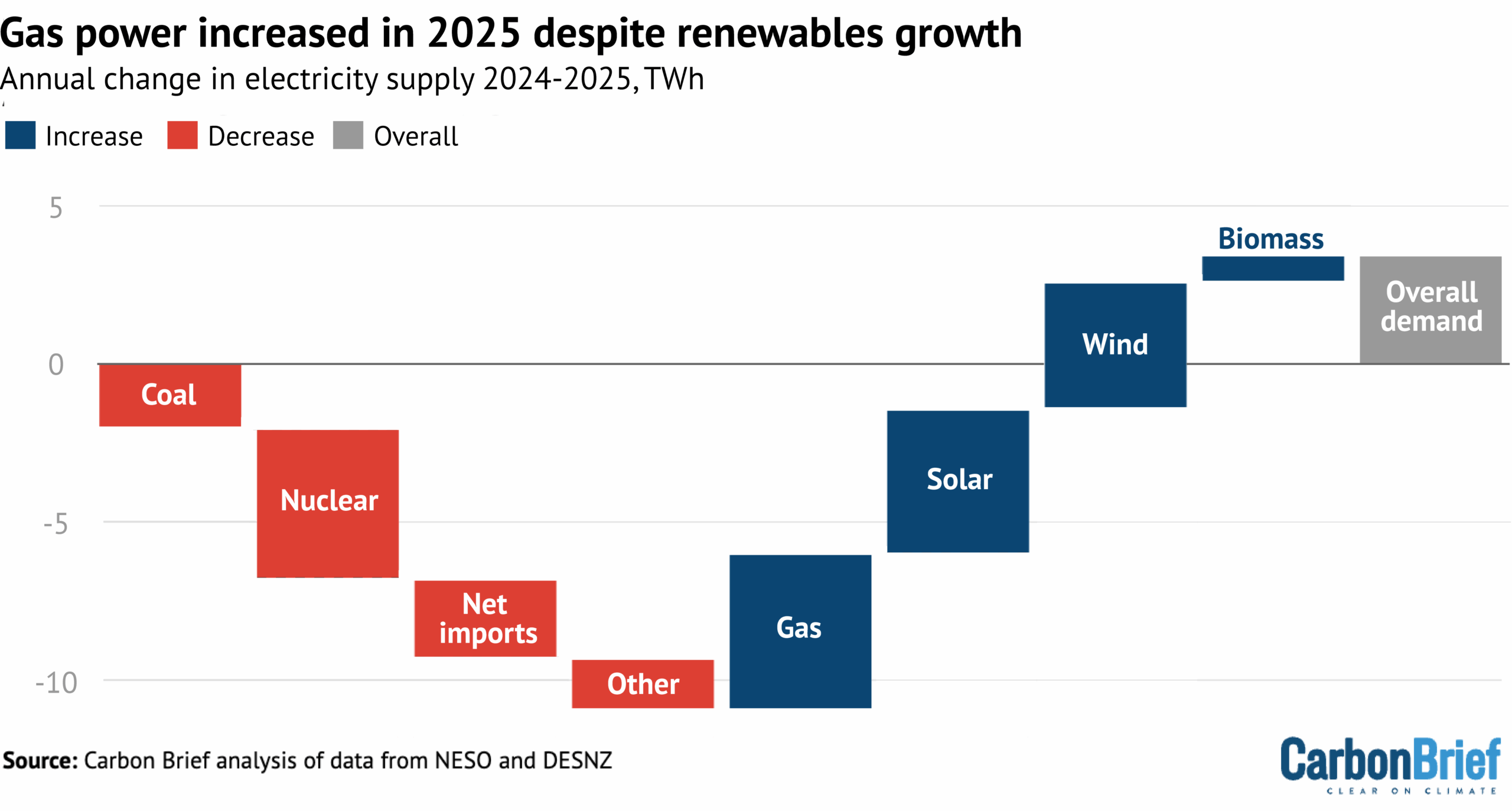

The UK’s fleet of wind, solar and biomass power plants all set new records in 2025, Carbon Brief analysis shows, but electricity generation from gas still went up.

The rise in gas power was due to the end of UK coal generation in late 2024 and nuclear power hitting its lowest level in half a century, while electricity exports grew and imports fell.

In addition, there was a 1% rise in UK electricity demand – after years of decline – as electric vehicles (EVs), heat pumps and data centres connected to the grid in larger numbers.

Other key insights from the data include:

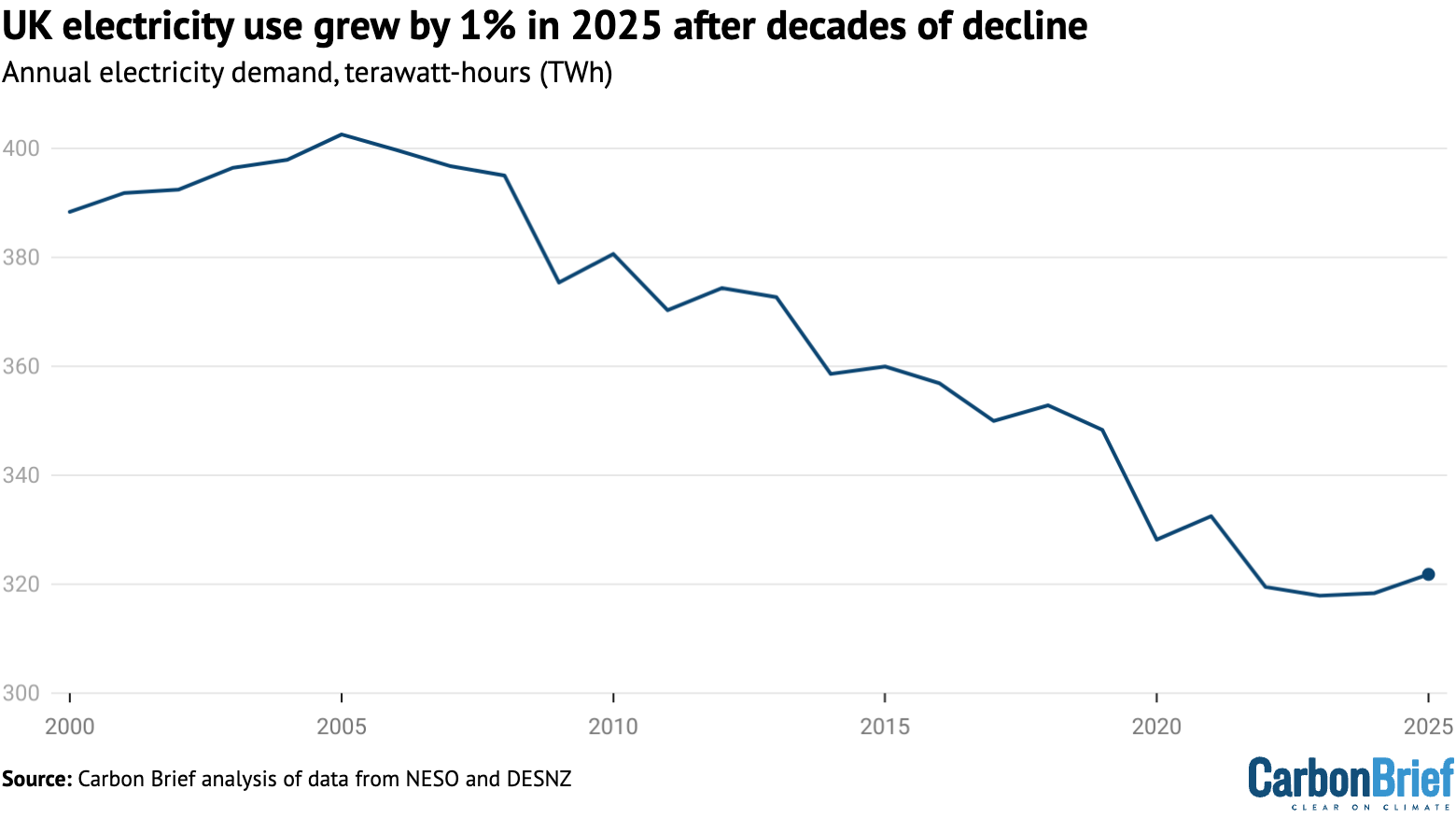

- Electricity demand grew for the second year in a row to 322 terawatt hours (TWh), rising by 4TWh (1%) and hinting at a shift towards steady increases, as the UK electrifies.

- Renewables supplied more of the UK’s electricity than any other source, making up 47% of the total, followed by gas (28%), nuclear (11%) and net imports (10%).

- The UK set new records for electricity generation from wind (87TWh, +5%), solar (19TWh, +31%) and biomass (41TWh, +2%), as well as for renewables overall (152TWh, +6%).

- The UK had its first full year without any coal power, compared with 2TWh of generation in 2024, ahead of the closure of the nation’s last coal plant in September of that year.

- Nuclear power was at its lowest level in half a century, generating just 36TWh (-12%), as most of the remaining fleet paused for refuelling or outages.

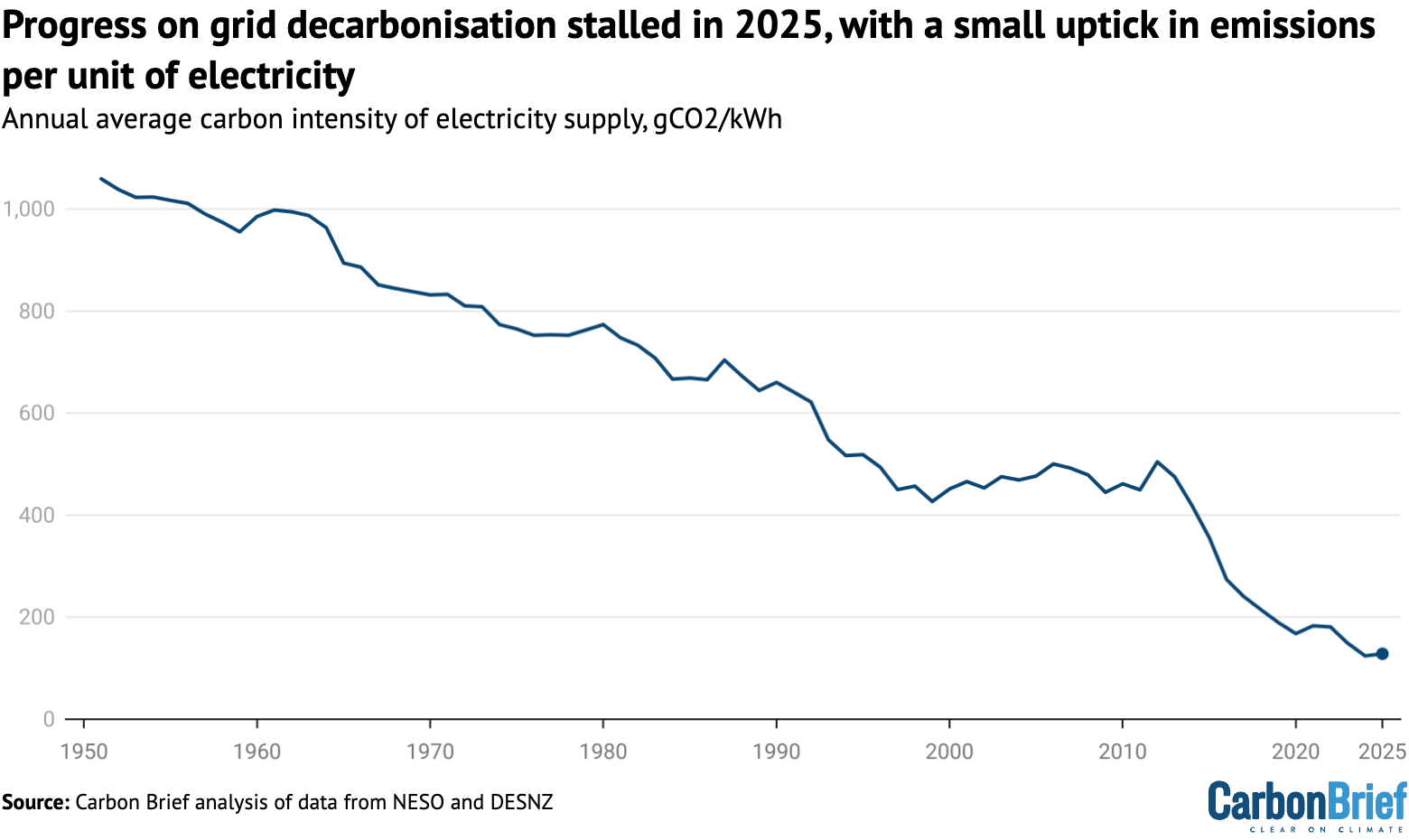

Overall, UK electricity became slightly more polluting in 2025, with each kilowatt hour linked to 126g of carbon dioxide (gCO2/kWh), up 2% from the record low of 124gCO2/kWh, set last year.

The National Energy System Operator (NESO) set a new record for the use of low-carbon sources – known as “zero-carbon operation” – reaching 97.7% for half an hour on 1 April 2025.

However, NESO missed its target of running the electricity network for at least 30 minutes in 2025 without any fossil fuels.

The UK inched towards separate targets set by the government, for 95% of electricity generation to come from low-carbon sources by 2030 and for this to cover 100% of domestic demand.

However, much more rapid progress will be needed to meet these goals.

Carbon Brief has published an annual analysis of the UK’s electricity generation in 2024, 2023, 2021, 2019, 2018, 2017 and 2016.

Record renewables

The UK’s fleet of renewable power plants enjoyed a record year in 2025, with their combined electricity generation reaching 152TWh, a 6% rise from a year earlier.

Renewables made up 47% of UK electricity supplies, another record high. The rise of renewables is shown in the figure below, which also highlights the end of UK coal power.

While the chart makes clear that gas-fired electricity generation has also declined over the past 15 years, there was a small rise in 2025, with output from the fuel reaching 91TWh. This was an increase of 5TWh (5%) and means gas made up 28% of electricity supplies overall.

The rise in gas-fired generation was the result of rising demand and another fall in nuclear power output, which reached the lowest level in half a century, while net imports and coal also declined.

The year began with the UK’s sunniest spring and by mid-December had already become the sunniest year on record. This contributed to a 5TWh (31%) surge in electricity generation from solar power, helped by a jump of roughly one-fifth in installed generating capacity.

The new record for solar power generation of 19TWh in 2025 comes after years of stagnation, with electricity output from the technology having climbed just 15% in five years.

The UK’s solar capacity reached 21GW in the third quarter of 2025. This is a substantial increase of 3 gigawatts (GW) or 18% year-on-year.

These are the latest figures available from the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ). The DESNZ timeseries has been revised to reflect previously missing data.

UK wind power also set a new record in 2025, reaching 87TWh, up 4TWh (5%). Wind conditions in 2025 were broadly similar to those in 2024, with the uptick in generation due to additional capacity.

The UK’s wind capacity reached 33GW in the third quarter of 2025, up 1GW (4%) from a year earlier. The 1.2GW Dogger Bank A in the North Sea has been ramping up since autumn 2025 and will be joined by the 1.2GW Dogger Bank B in 2026, as well as the 1.4GW Sofia project.

These sites were all awarded contracts during the government’s third “contracts for difference” (CfD) auction round and will be paid around £53 per megawatt hour (MWh) for the electricity they generate. This is well below current market prices, which currently sit at around £80/MWh.

Results from the seventh auction round, which is currently underway, will be announced in January and February 2026. Prices are expected to be significantly higher than in the third round, as a result of cost inflation.

Nevertheless, new offshore wind capacity is expected to be deliverable at “no additional cost to the billpayer”, according to consultancy Aurora Energy Research.

The UK’s biomass energy sites also had a record year in 2025, with output nudging up by 1TWh (2%) to 41TWh. Approximately two-thirds (roughly 27TWh) of this total is from wood-fired power plants, most notably the Drax former coal plant in Yorkshire, which generated 15TWh in 2024.

The government recently awarded new contracts to Drax that will apply from 2027 onwards and will see the amount of electricity it generates each year roughly halve, to around 6TWh. The government is also consulting on how to tighten sustainability rules for biomass sourcing.

Rising demand

The UK’s electricity demand has been falling for decades due to a combination of more efficient appliances and lightbulbs, as well as ongoing structural shifts in the economy.

Experts have been saying for years that at some point this trend would be reversed, as the UK shifts to electrified heat and transport supplies using EVs and heat pumps.

Indeed, the Climate Change Committee (CCC) has said that demand would more than double by 2050, with electrification forming a key plank of the UK’s efforts to reach net-zero.

Yet there has been little sign of this effect to date, with electricity demand continuing to fall outside single-year rebounds after economic shocks, such as the 2020 Covid lockdowns.

The data for 2025 shows hints that this turning point for electricity demand may finally be taking place. UK demand increased by 4TWh (1%) to 322TWh in 2025, after a 1TWh rise in 2024.

After declining for more than two decades since a peak in 2005, this is the first time in 20 years that UK demand has gone up for two years in a row, as shown in the figure below.

While detailed data on underlying electricity demand is not available, it is clear that the shift to EVs and heat pumps is playing an important role in the recent uptick.

There are now around 1.8m EVs on the UK’s roads and another 1m plug-in hybrids. Of this total, some 0.6m new EVs and plug-in hybrids were bought in 2025 alone. In addition, around 100,000 heat pumps are being installed each year. Sales of both technologies are rising fast.

Estimates from the NESO “future energy scenarios” point to an additional 2.0TWh of demand from new EVs in 2025, compared with 2024. They also suggest that newly installed heat pumps added around 0.2TWh of additional demand, while data centres added 0.4TWh.

By 2030, NESO’s scenarios suggest that electricity use for these three sources alone will rise by around 30TWh, equivalent to around 10% of total demand in 2025.

EVs would have the biggest impact, adding 17TWh to demand by 2030, NESO says, with heat pumps adding another 3TWh. Data-centre growth is highly uncertain, but could add 12TWh.

Gas growth

At the same time as UK electricity demand was growing by 4TWh in 2025, the country also lost a total of 10TWh of supply as a result of a series of small changes.

First, 2025 was the UK’s first full year without coal power since 1881, resulting in the loss of 2TWh of generation. Second, the UK’s nuclear fleet saw output falling to the lowest level in half a century, after a series of refuelling breaks and outages, which cut generation by 5TWh.

Third, after a big jump in imports in 2024, the UK saw a small decline in 2025, as well as a more notable increase in the amount of electricity exported to other countries. This pushed the country’s net imports down by 1TWh (4%).

The scale of cross-border trade in electricity is expected to increase as the UK has significantly expanded the number of interconnections with other markets.

However, the government’s clean-power targets for 2030 imply that the UK would become a net exporter, sending more electricity overseas than it receives from other countries. At present, it remains a significant net importer, with these contributions accounting for 109% of supplies.

Finally, other sources of generation – including oil – also declined in 2025, reducing UK supplies by another 2TWh, as shown in the figure below.

These losses in UK electricity supply were met by the already-mentioned increases in generation from gas, solar, wind and biomass, as shown in the figure above.

The government’s targets for decarbonising the UK’s electricity supplies will face similar challenges in the years to come as electrification – and, potentially, data centres – continue to push up demand.

All but one of the UK’s existing nuclear power plants are set to retire by 2030, meaning the loss of another 27TWh of nuclear generation.

This will be replaced by new nuclear capacity, but only slowly. The 3.2GW Hinkley Point C plant in Somerset is set to start operating in 2030 at the earliest and its sister plant, Sizewell C in Suffolk, not until at least another five years later.

Despite backing from ministers for small modular reactors, the timeline for any buildout is uncertain, with the latest government release referring to the “mid-2030s”.

Meanwhile, biomass generation is likely to decline as the output of Drax is scaled back from 2027.

Stalling progress

Taken together, the various changes in the UK’s electricity supplies in 2025 mean that efforts to decarbonise the grid stalled, with a small increase in emissions per unit of generation.

The 2% increase in carbon intensity to 126gCO2/kWh is illustrated in the figure below and comes after electricity was the “cleanest ever” in 2024, at 124gCO2/kWh.

The stalling progress on cleaning up the UK’s grid reflects the balance of record renewables, rising demand and rising gas generation, along with poor output from nuclear power.

Nevertheless, a series of other new records were set during 2025.

NESO ran the transmission grid on the island of Great Britain (GB; namely, England, Wales and Scotland) with a record 97.7% “zero-carbon operation” (ZCO) on 1 April 2025.

Note that this measure excludes gas plants that also generate heat – known as combined heat and power, or CHP – as well as waste incinerators and all other generators that do not connect to the transmission network, which means that it does not include most solar or onshore wind.

NESO was unable to meet its target – first set in 2019 – for 100% ZCO during 2025, meaning it did not succeed in running the transmission grid without any fossil fuels for half an hour.

Other records set in 2025 include:

- GB ran on 100% clean power, after accounting for exports, for a record 87 hours in 2025, up from 64.5 hours in 2024.

- Total GB renewable generation from wind, solar, biomass and hydro reached a record 31.3GW from 13:30-14:00 on 4 July 2025, meeting 84% of demand.

- GB wind generation reached a record 23.8GW for half an hour on 5 December 2025, when it met 52% of GB demand.

- GB solar reached a record 14.0GW at 13:00 on 8 July 2025, when it met 40% of demand.

The government has separate targets for at least 95% of electricity generation and 100% of demand on the island of Great Britain to come from low-carbon sources by 2030.

These goals, similar to the NESO target, exclude Northern Ireland, CHP and waste incinerators. However, they include distributed renewables, such as solar and onshore wind.

These definitions mean it is hard to measure progress independently. The most recent government figures show that 74% of qualifying generation in GB was from low-carbon sources in 2024.

Carbon Brief’s figures for the whole UK show that low-carbon sources made up a record 58% of electricity supplies overall in 2025, up marginally from a year earlier.

Similarly, low-carbon sources made up 65% of electricity generation in the UK overall. This was unchanged from a year earlier.

Methodology

The figures in the article are from Carbon Brief analysis of data from DESNZ Energy Trends, chapter 5 and chapter 6, as well as from NESO. The figures from NESO are for electricity supplied to the grid in Great Britain only and are adjusted here to include Northern Ireland.

In Carbon Brief’s analysis, the NESO numbers are also adjusted to account for electricity used by power plants on site and for generation by plants not connected to the high-voltage national grid.

NESO already includes estimates for onshore windfarms, but does not cover industrial gas combined heat and power plants and those burning landfill gas, waste or sewage gas.

Carbon intensity figures from 2009 onwards are taken directly from NESO. Pre-2009 estimates are based on the NESO methodology, taking account of fuel use efficiency for earlier years.

The carbon intensity methodology accounts for lifecycle emissions from biomass. It includes emissions for imported electricity, based on the daily electricity mix in the country of origin.

DESNZ historical electricity data, including years before 2009, is adjusted to align with other figures and combined with data on imports from a separate DESNZ dataset. Note that the data prior to 1951 only includes “major” power producers.

The post Analysis: UK renewables enjoy record year in 2025 – but gas power still rises appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: UK renewables enjoy record year in 2025 – but gas power still rises

-

Greenhouse Gases5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval