Saudi Arabia and Pakistan were among the top importers of Chinese solar panels in 2024, with more than half heading to countries in the global south.

The findings come from Ember’s China’s solar PV export explorer, which tracks shipments to more than 200 countries and was recently updated with figures for the full year of 2024.

In total, China’s solar panel exports rose by 10% in 2024, with imports by global-south countries rising by 32% and those to the global north falling by 6%.

This means Chinese exports grew less quickly than the 30% rise in solar installations outside China last year, indicating that other countries have been boosting their own solar manufacturing capacity and that already-imported stocks were being run down.

Apart from Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, which both witnessed different solar booms last year, there was also a sharp uptick in sales to many small African and Latin American countries in late 2024, suggesting that China may be finding new markets for its solar exports.

China itself – the biggest of all the global-south solar markets – installed more solar panels than it exported for the second year in a row.

This article analyses the latest trends from China’s solar export data, highlighting the markets currently seeing record growth and the trends that underlie this.

Global-south sales surge

China’s exports of solar panels to the global south have doubled in the past two years, overtaking global-north sales for the first time since 2018, according to data collated in the Ember export explorer.

Global-south imports more than doubled from 60 gigawatts (GW) in 2022 to 126GW in 2024. That surpassed global-north imports, which were only 12% more in 2024 than in 2022, as shown on the chart below.

Biggest solar importers

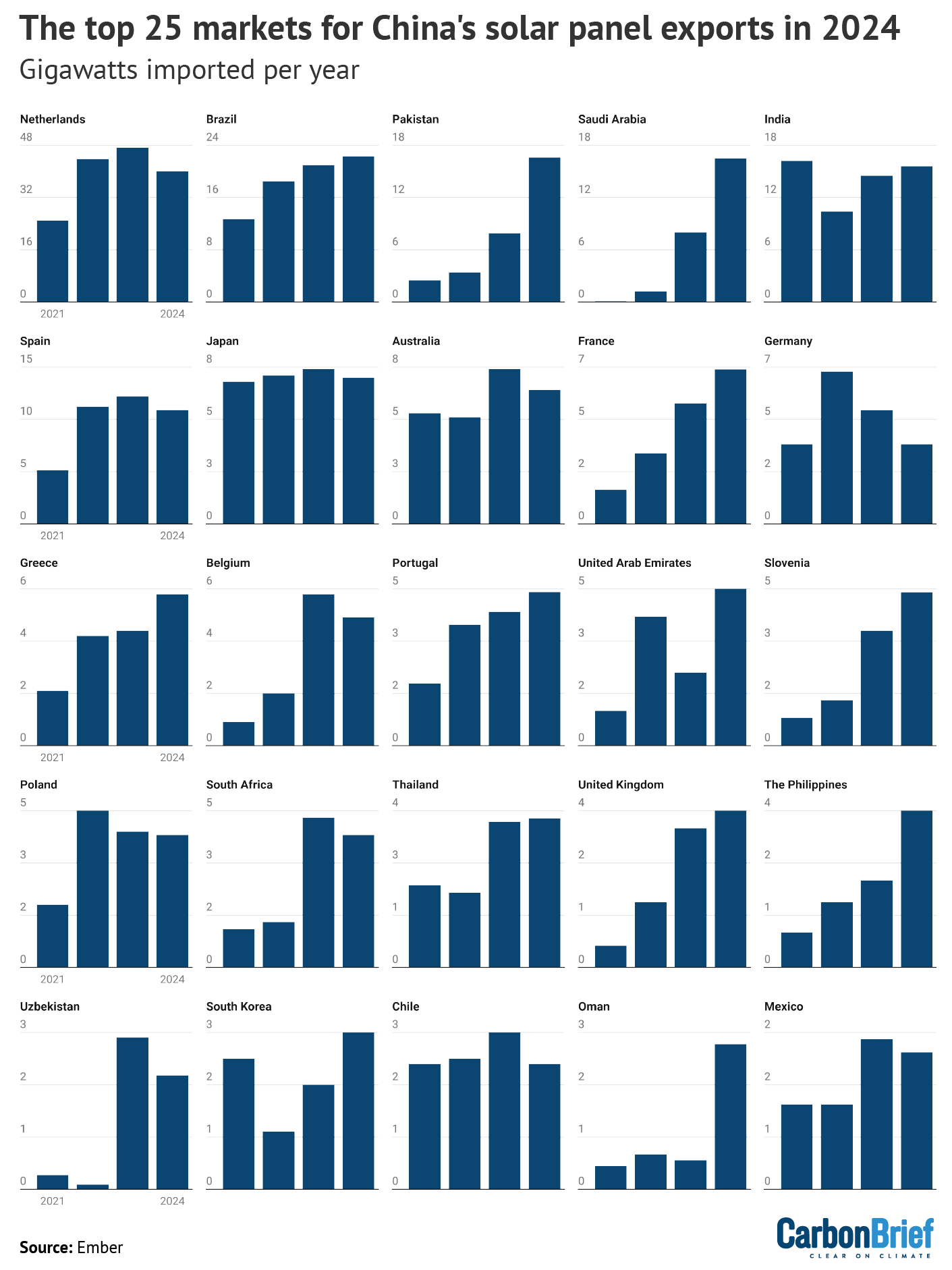

The Netherlands was the biggest importer in 2024 and has been every year since 2019, as a result of Rotterdam serving as an import hub for much of continental Europe. The following four places were all global-south countries, the data shows.

Brazil was in second place again, importing more than 20GW for the second year in a row. However, the imposition of import taxes by the government, the refusal of electricity distributors to connect new solar systems and solar “curtailment” are all causing headwinds in 2025.

Pakistan and Saudi Arabia jumped to third and fourth, respectively. (The next section charts the rise of these two very different solar giants, from the 12th and 26th biggest importers, respectively, in 2022 into the top five.)

India was in fifth place in 2024. Its module imports remained similar to those in 2023, but its installations rose to a record high, enabled by a step up in new domestic solar panel manufacturing capacity.

In January 2025, that helped India hit 100GW of solar installed, according to government figures. India is partly relying on Chinese imports, whilst simultaneously scaling up its own manufacturing industry.

The other large global-south markets – identified in the export explorer data – are also spread across the world, as shown in the figure below.

They include the UAE and Oman in the Middle East, Thailand and the Philippines in south-east Asia and then South Africa, Chile, Uzbekistan and Mexico.

Pakistan and Saudi Arabia

Pakistan and Saudi Arabia have had almost identical imports of Chinese solar panels for the past two years. They stood at 8GW in 2023 and then more than doubled to 17GW in 2024, placing them as the third and fourth largest importers in the world, the export explorer shows. Their monthly imports from China are shown in the figure below.

However, that is where the similarities end. Pakistan’s growth has come almost entirely from small-scale “distributed” installations, without co-located battery storage and paid for by consumers. Saudi Arabia’s growth has come almost entirely from desert solar farms, complete with some battery storage and paid for by international energy companies.

Pakistan’s solar boom was ignited by spiralling electricity costs and chronic power shortages, which have put energy at the heart of the country’s economic problems.

The country installed 10-15GW of solar in 2024 alone, according to Bloomberg estimates. Pakistan’s peak electricity demand was just 30GW in 2023, which gives an idea of how big solar has become in the country.

Large utility-scale solar is minimal – only 0.63GW of such capacity is operational. Instead, almost all of the new solar capacity was installed on rooftops or next to factories or fields, for direct use by consumers.

However, hardly any battery capacity was installed alongside the new solar panels, meaning people and companies still rely on the grid for electricity outside of sunny hours.

The surge in solar capacity has helped drive down electricity generation from fossil fuels, despite fast-growing electricity demand. However, it also “threatens to disrupt” the grid, where demand has created at the same time as becoming more variable.

Turning to Saudi Arabia, solar panels are used mostly in large desert renewable auction tenders. There have been five solar tender rounds in 2017, 2019, 2021, 2023 and 2024.

The latest tender round contracted 3.7GW of large-scale desert solar parks, achieving the cheapest reported electricity prices in the world of $13 (£10) per megawatt hour. (Note that these reported prices are somewhat artificial and are likely to underestimate the full cost.)

None of the winning solar parks were contracted with batteries. However, parallel battery tender rounds are now commencing.

There are estimated to be only 3.3GW of solar projects currently operational in Saudi Arabia, but a further 5.4GW are under construction. The solar plant owners are international energy firms including KEPCO, EDF Renewables, Masdar and TotalEnergies, as well as Saudi companies.

The country plans to move from near-zero renewables in 2020 to 50% of its total electricity generation coming from renewables in 2030. In relative terms, this is one of the most ambitious renewable targets anywhere in the world.

New markets

There were 15 countries that saw a large uptick in imports of Chinese solar panels towards the end of 2024, according to the export explorer data and shown in the figure below.

There were large increases in Nigeria, Algeria and Iraq, where there is clear evidence that demand for panels is growing.

For example, Nigeria’s growth was driven by blackouts in 2024 and the removal of fuel subsidies, making diesel generators more expensive to run.

Iraq is currently constructing its first large solar plant, while another 7.5GW of projects were approved by the government in 2024 to meet growing electricity demand.

Meanwhile, Algeria has a plan for 3GW of solar projects, which is now underway.

For a cluster of a further 12 countries, it is less clear if the recent uptick in solar panel imports is a structural change that will continue into 2025 and beyond.

There are large incentives for China’s solar manufacturing companies to meet year-end targets, so it is possible that containers of solar panels were sold at discounted rates to help meet these goals.

The cluster includes many small African countries – Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Djibouti and Guinea – and Latin American countries – Ecuador, El Salvador, Guyana and Nicaragua.

The December 2024 imports are quite large in the context of the small electricity systems of many of these countries. As such, these solar panels would provide a relatively meaningful increase in renewable electricity generation if they go on to be installed.

China installs more than exports

China has not just been exporting growing numbers of solar panels. – In 2024, it installed more solar panels than it exported for the second year running, according to Ember analysis.

Indeed, China installed 333GW of solar capacity domestically in 2024, some 38% more than the 242GW of solar panels that it exported, as shown in the figure below.

From 2019 to 2022, China had been exporting more solar panels overseas than it installed domestically. However, that changed when China’s solar panel installations surged from 103GW in 2022 to 260GW in 2023.

By the end of 2024, China had a total installed solar capacity of 1,064GW, making it the first country to achieve the 1 terawatt (TW) benchmark.

Reducing reliance on China

China’s solar exports grew for the seventh consecutive year in 2024, rising to a record 242GW, Ember’s data shows.

Exports rose by 10% year-on-year, which was a significant slowdown from the rate of growth seen in recent years. However, solar installations outside of China grew by 30%.

This demonstrates a step-up in ambitions to reduce reliance on Chinese solar panel imports by a number of countries around the world.

For example, India’s solar panel manufacturing capacity has skyrocketed in recent years. In 2023, it added 23GW and a further 11GW was completed in the first half of 2024. India’s reported module and cell production capacities stood at around 80GW and 7GW, respectively, as of March 2025.

However, the country still relies on imported Chinese solar cells. The value of shipments to India rose 30% from $970m in 2023 to $1.3bn in 2024, accounting for almost half (48%) of China’s cell exports.

This reliance is seen as a temporary but essential part of the transition to full India manufacturing capability, as solar cell manufacturing capacity steps up, with the aim that projects contracted through the government solar auctions only use locally-sourced cells from June 2026.

The EU is on track to meet its 30GW of solar panel manufacturing target in 2025. However, the numbers are relatively small compared to other regions. Europe had 22GW of solar module manufacturing capacity in 2024, with 12GW in the construction pipeline.

The US does not import Chinese panels, but it does rely heavily on imports from other Asian countries. It imported 51GW of solar panels in the first 10 months of 2024, more than 90% of which were from Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, India or Cambodia.

US manufacturing capacity rose from 7GW in 2020 to 50GW in early 2025, with plans announced for a further 56GW, according to trade association the Solar Energy Industries Association.

The post Guest post: Saudi Arabia’s surprisingly large imports of solar panels from China appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: Saudi Arabia’s surprisingly large imports of solar panels from China

Climate Change

Greenpeace organisations to appeal USD $345 million court judgment in Energy Transfer’s intimidation lawsuit

SYDNEY, Saturday 28 February 2026 — Greenpeace International and Greenpeace organisations in the US announce they will seek a new trial and, if necessary, appeal the decision with the North Dakota Supreme Court following a North Dakota District Court judgment today awarding Energy Transfer (ET) USD $345 million.

ET’s SLAPP suit remains a blatant attempt to silence free speech, erase Indigenous leadership of the Standing Rock movement, and punish solidarity with peaceful resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Greenpeace International will also continue to seek damages for ET’s bullying lawsuits under EU anti-SLAPP legislation in the Netherlands.

Mads Christensen, Greenpeace International Executive Director said: “Energy Transfer’s attempts to silence us are failing. Greenpeace International will continue to resist intimidation tactics. We will not be silenced. We will only get louder, joining our voices to those of our allies all around the world against the corporate polluters and billionaire oligarchs who prioritise profits over people and the planet.

“With hard-won freedoms under threat and the climate crisis accelerating, the stakes of this legal fight couldn’t be higher. Through appeals in the US and Greenpeace International’s groundbreaking anti-SLAPP case in the Netherlands, we are exploring every option to hold Energy Transfer accountable for multiple abusive lawsuits and show all power-hungry bullies that their attacks will only result in a stronger people-powered movement.”

The Court’s final judgment today rejects some of the jury verdict delivered in March 2025, but still awards hundreds of millions of dollars to ET without a sound basis in law. The Greenpeace defendants will continue to press their arguments that the US Constitution does not allow liability here, that ET did not present evidence to support its claims, that the Court admitted inflammatory and irrelevant evidence at trial and excluded other evidence supporting the defense, and that the jury pool in Mandan could not be impartial.[1][2]

ET’s back-to-back lawsuits against Greenpeace International and the US organisations Greenpeace USA (Greenpeace Inc.) and Greenpeace Fund are clear-cut examples of SLAPPs — lawsuits attempting to bury nonprofits and activists in legal fees, push them towards bankruptcy and ultimately silence dissent.[3] Greenpeace International, which is based in the Netherlands, is pursuing justice in Europe, with a suit against ET under Dutch law and the European Union’s new anti-SLAPP directive, a landmark test of the new legislation which could help set a powerful precedent against corporate bullying.[4]

Kate Smolski, Program Director at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, said: “This is part of a worrying trend globally: fossil fuel corporations are increasingly using litigation to attack and silence ordinary people and groups using the law to challenge their polluting operations — and we’re not immune to these tactics here in Australia.

“Rulings like this have a chilling effect on democracy and public interest litigation — we must unite against these silencing tactics as bad for Australians and bad for our democracy. Our movement is stronger than any corporate bully, and grows even stronger when under attack.”

Energy Transfer’s SLAPPs are part of a wave of abusive lawsuits filed by Big Oil companies like Shell, Total, and ENI against Greenpeace entities in recent years.[3] A couple of these cases have been successfully stopped in their tracks. This includes Greenpeace France successfully defeating TotalEnergies’ SLAPP on 28 March 2024, and Greenpeace UK and Greenpeace International forcing Shell to back down from its SLAPP on 10 December 2024.

-ENDS-

Images available in Greenpeace Media Library

Notes:

[1] The judgment entered by North Dakota District Court Judge Gion follows a jury verdict finding Greenpeace entities liable for more than US$660 million on March 19, 2025. Judge Gion subsequently threw out several items from the jury’s verdict, reducing the total damages to approximately US$345 million.

[2] Public statements from the independent Trial Monitoring Committee

[3] Energy Transfer’s first lawsuit was filed in federal court in 2017 under the RICO Act – the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a US federal statute designed to prosecute mob activity. The case was dismissed in 2019, with the judge stating the evidence fell “far short” of what was needed to establish a RICO enterprise. The federal court did not decide on Energy Transfer’s claims based on state law, so Energy Transfer promptly filed a new case in a North Dakota state court with these and other state law claims.

[4] Greenpeace International sent a Notice of Liability to Energy Transfer on 23 July 2024, informing the pipeline giant of Greenpeace International’s intention to bring an anti-SLAPP lawsuit against the company in a Dutch Court. After Energy Transfer declined to accept liability on multiple occasions (September 2024, December 2024), Greenpeace International initiated the first test of the European Union’s anti-SLAPP Directive on 11 February 2025 by filing a lawsuit in Dutch court against Energy Transfer. The case was officially registered in the docket of the Court of Amsterdam on 2 July, 2025. Greenpeace International seeks to recover all damages and costs it has suffered as a result of Energy Transfers’s back-to-back, abusive lawsuits demanding hundreds of millions of dollars from Greenpeace International and the Greenpeace organisations in the US. The next hearing in the Court of Amsterdam is scheduled for 16 April, 2026.

Media contact:

Kate O’Callaghan on 0406 231 892 or kate.ocallaghan@greenpeace.org

Climate Change

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

The Trump administration’s relentless rollback of public health and environmental protections has allowed widespread toxic exposures to flourish, warn experts who helped implement safeguards now under assault.

In a new report that outlines a dozen high-risk pollutants given new life thanks to weakened, delayed or rescinded regulations, the Environmental Protection Network, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group of hundreds of former Environmental Protection Agency staff, warns that the EPA under President Donald Trump has abandoned the agency’s core mission of protecting people and the environment from preventable toxic exposures.

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

Climate Change

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

The country’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas benefited from what critics say is a questionable IRS interpretation of tax credits.

Cheniere Energy, the largest producer and exporter of U.S. liquefied natural gas, received $370 million from the IRS in the first quarter of 2026, a payout that shipping experts, tax specialists and a U.S. senator say the company never should have received.

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits