Solar geoengineering has been suggested as a temporary measure to buy time for the emissions cuts needed to stabilise global temperatures.

These arguments have generally considered geoengineering as an independent component of the “toolbox” of options for climate change mitigation.

However, this perspective overlooks the knock-on effects that pursuing solar geoengineering could have on reaching net-zero.

The idea of solar geoengineering is to reduce global temperatures by reflecting more of the sun’s incoming radiation away from the Earth’s surface. One of the most talked-about approaches is stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI), which involves the injection of aerosols in an upper layer of the atmosphere.

In a pair of studies, published in Earth System Dynamics and Earth’s Future, we explore the potential impact that deploying SAI could have on the potential to generate wind and solar energy.

Our findings show that SAI could slow decarbonisation efforts by reducing the output of these energy systems. In this way, solar geoengineering could create an additional challenge to reaching net-zero, thus creating further obstacles for avoiding dangerous warming.

Buying time with temporary geoengineering

One of the criticisms of solar geoengineering is that its pursuit could obstruct or discourage ongoing and future efforts to cut emissions, sometimes referred to as mitigation deterrence. While the evidence of this is limited, what about the technological implications that could constrain efforts to reduce emissions?

To tackle this question, we have undertaken two studies into how SAI could affect the potential for solar and wind energy – key renewable sources in the transition to net-zero.

Our experiments focus on a scenario where SAI is used to bring global temperatures down from a very high-warming pathway (SSP5-8.5) that represents a failure of climate policy – to a moderate-warming pathway broadly in line with current policies (SSP2-4.5).

We compare the scenarios in the last decade of the simulations, the 2090s, where the signal of human-caused climate change is strongest.

The chart below illustrates the absolute warming levels for these pathways – showing climate model simulations for the moderate (grey lines), high (black) and SAI (red). The red bar shows the decade of interest at the end of the 21st century.

Under these pathways, end of century warming would be 2.2C lower in the SAI scenario than under high warming.

We focus on three different dimensions that help determine renewable energy potential and calculate these for each grid cell and each timestep of our simulations:

- A politico-economic dimension that assesses suitability based on land cover, regulatory restrictions and distance to population.

- The physical entity that represents the unconstrained energy resource, such as radiation, wind speed and temperature.

- The technical aspects related to conversion losses from turning energy from the sun or wind into electricity. This depends on characteristics related to solar panels or wind turbines and the density of their placement in a wind or solar farm.

These dimensions, and their interactions, are illustrated in the figure below, divided between politico-economic (green), technical (blue) and physical (purple).

Extended periods of low solar

Our results indicate that the potential for solar energy, whether compared to a moderate emissions scenario or the high emissions baseline, would be reduced in almost all parts of the world if SAI is used.

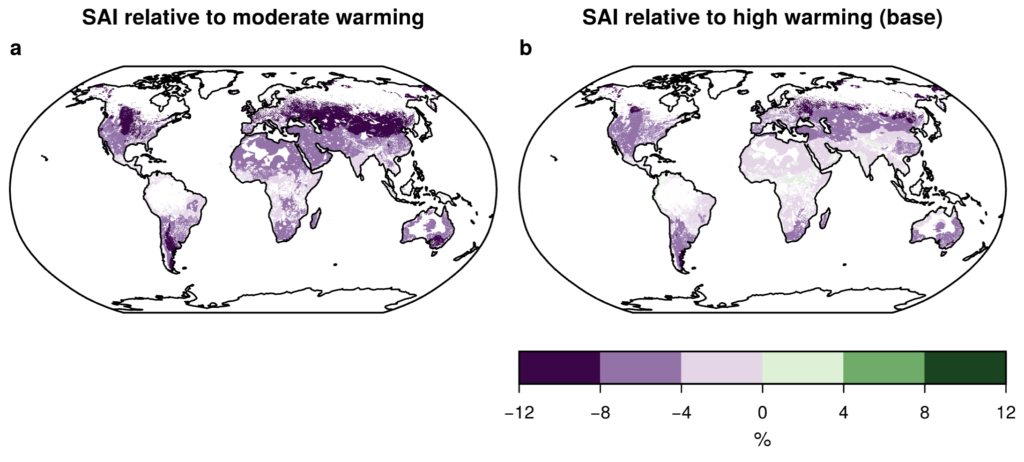

The maps below show the increase (green shading) and decrease (purple) in solar energy potential in the SAI scenario relative to the moderate (left) and high (right) warming scenarios.

We find typically larger differences under moderate warming than high warming because solar energy potential is larger in a world where global temperatures are not raised as high. Solar panel efficiency is reduced substantially in a much-warmer world.

Geographically, the largest relative reductions are in the mid-to-high latitudes. (This is due to solar geometry, which dictates that the sun’s rays arrive at a lower angle for higher latitudes, meaning they have to pass through more aerosol particles on their way to the surface.)

However, perhaps even more importantly, using SAI enhances the frequency of extended periods with low solar potential.

As the principle of SAI is to reduce incoming solar radiation, a fall in solar energy potential is to be expected.

Yet, there are actually two impacts of SAI that favour solar power: a thinning of tropical clouds, which compensates for some of the direct reduction of incoming sunlight, and lower ambient temperatures compared to the high-warming scenario, which benefit the efficiency of solar panels.

However, neither of these two impacts outweighs the overall reduction in solar power potential.

SAI may also affect how solar panels are positioned. Typically, panels are tilted to maximise the amount of direct radiation reaching the panels surface. However, under SAI, we find that radiation reaching the panels is less direct and increasingly diffuse. Therefore, tilting solar panels may become less useful.

Regional reductions in wind potential

Our findings suggest that changes in on- and offshore wind potential under SAI can be of a similar magnitude to those for solar, but whether the impact causes an increase or decrease in energy potential is highly variable depending on the location and season.

Overall, these changes lead to a negligible global impact on wind potential, but the regional charges can still be significant – with particular reductions in China and central Asia, along with Mexico, western US and many parts of the southern hemisphere.

This is shown in the maps below, which illustrate the increase (green) and decrease (purple) in offshore wind energy potential in the SAI scenario relative to the moderate (left) and high (right) warming scenarios.

The changes in wind potential under SAI are caused by changes in large-scale atmospheric circulation – mainly a result of the heat absorbed by the injected aerosols.

The impact on wind potential is more nuanced than for solar. For example, there is a general long-term slowing of surface winds under SAI. (This has also been observed in simulations using a different climate model from the one used in our study.)

However, due to the delicate range of wind speeds where wind turbines operate, slower winds can actually lead to either an increase or a decrease in potential.

Of course, changes in wind energy potential are only realised if the areas are actually exploited for wind energy. However, the large regional changes in wind potential may imply that a different strategy would be needed for siting windfarms in order to maximise the energy produced. However, this would cause problems later down the line if SAI is intended as a temporary measure.

Implications for decarbonisation

With a reduced potential for wind and solar when using SAI, there is a risk that deploying SAI would actually lead to a slowing of decarbonisation.

This, in turn, implies that solar geoengineering would need to be deployed for even longer – unless the gap could be met with higher amounts of carbon dioxide removal. Other research has found that, once started, geoengineering would be required for multiple centuries.

Such knock-on impacts put the concept of using geoengineering to “buy time” for climate change mitigation into question.

In fact, because of the reduced output of renewables under SAI, relatively more renewable capacity would need to be installed just to produce the same amount of energy as without SAI.

At the same time, renewable technology may also need to be adapted to SAI circulation and radiation conditions for optimal energy production. This could include adjusting the tilt of solar panels and adapting windfarm placement strategy and wind turbine characteristics.

The substantial impact geoengineering could have on mitigation – and vice versa – highlights the importance of considering such couplings when moving towards more comprehensive assessments of climate geoengineering.

The post Guest post: How solar geoengineering could disrupt wind and solar power appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: How solar geoengineering could disrupt wind and solar power

Climate Change

A Tiny Caribbean Island Sued the Netherlands Over Climate Change, and Won

The case shows that climate change is a fundamental human rights violation—and the victory of Bonaire, a Dutch territory, could open the door for similar lawsuits globally.

From our collaborating partner Living on Earth, public radio’s environmental news magazine, an interview by Paloma Beltran with Greenpeace Netherlands campaigner Eefje de Kroon.

A Tiny Caribbean Island Sued the Netherlands Over Climate Change, and Won

Climate Change

Greenpeace organisations to appeal USD $345 million court judgment in Energy Transfer’s intimidation lawsuit

SYDNEY, Saturday 28 February 2026 — Greenpeace International and Greenpeace organisations in the US announce they will seek a new trial and, if necessary, appeal the decision with the North Dakota Supreme Court following a North Dakota District Court judgment today awarding Energy Transfer (ET) USD $345 million.

ET’s SLAPP suit remains a blatant attempt to silence free speech, erase Indigenous leadership of the Standing Rock movement, and punish solidarity with peaceful resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Greenpeace International will also continue to seek damages for ET’s bullying lawsuits under EU anti-SLAPP legislation in the Netherlands.

Mads Christensen, Greenpeace International Executive Director said: “Energy Transfer’s attempts to silence us are failing. Greenpeace International will continue to resist intimidation tactics. We will not be silenced. We will only get louder, joining our voices to those of our allies all around the world against the corporate polluters and billionaire oligarchs who prioritise profits over people and the planet.

“With hard-won freedoms under threat and the climate crisis accelerating, the stakes of this legal fight couldn’t be higher. Through appeals in the US and Greenpeace International’s groundbreaking anti-SLAPP case in the Netherlands, we are exploring every option to hold Energy Transfer accountable for multiple abusive lawsuits and show all power-hungry bullies that their attacks will only result in a stronger people-powered movement.”

The Court’s final judgment today rejects some of the jury verdict delivered in March 2025, but still awards hundreds of millions of dollars to ET without a sound basis in law. The Greenpeace defendants will continue to press their arguments that the US Constitution does not allow liability here, that ET did not present evidence to support its claims, that the Court admitted inflammatory and irrelevant evidence at trial and excluded other evidence supporting the defense, and that the jury pool in Mandan could not be impartial.[1][2]

ET’s back-to-back lawsuits against Greenpeace International and the US organisations Greenpeace USA (Greenpeace Inc.) and Greenpeace Fund are clear-cut examples of SLAPPs — lawsuits attempting to bury nonprofits and activists in legal fees, push them towards bankruptcy and ultimately silence dissent.[3] Greenpeace International, which is based in the Netherlands, is pursuing justice in Europe, with a suit against ET under Dutch law and the European Union’s new anti-SLAPP directive, a landmark test of the new legislation which could help set a powerful precedent against corporate bullying.[4]

Kate Smolski, Program Director at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, said: “This is part of a worrying trend globally: fossil fuel corporations are increasingly using litigation to attack and silence ordinary people and groups using the law to challenge their polluting operations — and we’re not immune to these tactics here in Australia.

“Rulings like this have a chilling effect on democracy and public interest litigation — we must unite against these silencing tactics as bad for Australians and bad for our democracy. Our movement is stronger than any corporate bully, and grows even stronger when under attack.”

Energy Transfer’s SLAPPs are part of a wave of abusive lawsuits filed by Big Oil companies like Shell, Total, and ENI against Greenpeace entities in recent years.[3] A couple of these cases have been successfully stopped in their tracks. This includes Greenpeace France successfully defeating TotalEnergies’ SLAPP on 28 March 2024, and Greenpeace UK and Greenpeace International forcing Shell to back down from its SLAPP on 10 December 2024.

-ENDS-

Images available in Greenpeace Media Library

Notes:

[1] The judgment entered by North Dakota District Court Judge Gion follows a jury verdict finding Greenpeace entities liable for more than US$660 million on March 19, 2025. Judge Gion subsequently threw out several items from the jury’s verdict, reducing the total damages to approximately US$345 million.

[2] Public statements from the independent Trial Monitoring Committee

[3] Energy Transfer’s first lawsuit was filed in federal court in 2017 under the RICO Act – the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a US federal statute designed to prosecute mob activity. The case was dismissed in 2019, with the judge stating the evidence fell “far short” of what was needed to establish a RICO enterprise. The federal court did not decide on Energy Transfer’s claims based on state law, so Energy Transfer promptly filed a new case in a North Dakota state court with these and other state law claims.

[4] Greenpeace International sent a Notice of Liability to Energy Transfer on 23 July 2024, informing the pipeline giant of Greenpeace International’s intention to bring an anti-SLAPP lawsuit against the company in a Dutch Court. After Energy Transfer declined to accept liability on multiple occasions (September 2024, December 2024), Greenpeace International initiated the first test of the European Union’s anti-SLAPP Directive on 11 February 2025 by filing a lawsuit in Dutch court against Energy Transfer. The case was officially registered in the docket of the Court of Amsterdam on 2 July, 2025. Greenpeace International seeks to recover all damages and costs it has suffered as a result of Energy Transfers’s back-to-back, abusive lawsuits demanding hundreds of millions of dollars from Greenpeace International and the Greenpeace organisations in the US. The next hearing in the Court of Amsterdam is scheduled for 16 April, 2026.

Media contact:

Kate O’Callaghan on 0406 231 892 or kate.ocallaghan@greenpeace.org

Climate Change

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

The Trump administration’s relentless rollback of public health and environmental protections has allowed widespread toxic exposures to flourish, warn experts who helped implement safeguards now under assault.

In a new report that outlines a dozen high-risk pollutants given new life thanks to weakened, delayed or rescinded regulations, the Environmental Protection Network, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group of hundreds of former Environmental Protection Agency staff, warns that the EPA under President Donald Trump has abandoned the agency’s core mission of protecting people and the environment from preventable toxic exposures.

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits