Growing tall trees to provide shade for cocoa plantations in west Africa could sequester millions of tonnes of carbon, according to a new study.

The research, published in Nature Sustainability, finds that the additional carbon stored in shade trees, such as banana and palm trees, could entirely “offset” cocoa-related emissions in Ghana and Ivory Coast, without reducing production.

West Africa produces about 60% of the world’s cocoa, which is one of the most emissions-intensive crops to grow.

The authors map the shade provided by trees across cocoa agricultural systems in west Africa, then project how much additional carbon storage would be created by expanding it.

An author of the study tells Carbon Brief that cocoa plantations have been a “big” driver of deforestation and the emissions it causes, but the findings show that there is “huge potential” for cocoa to be “part of the solution”.

Cocoa plantations

Cocoa trees thrive in rainforests, as they need abundant rain, high humidity and stable temperatures. They often grow under the shadow of other plants, such as bananas, plantains and palm trees.

Two countries in west Africa – Ivory Coast and Ghana – dominate global cocoa production and are major exporters to the US and Europe.

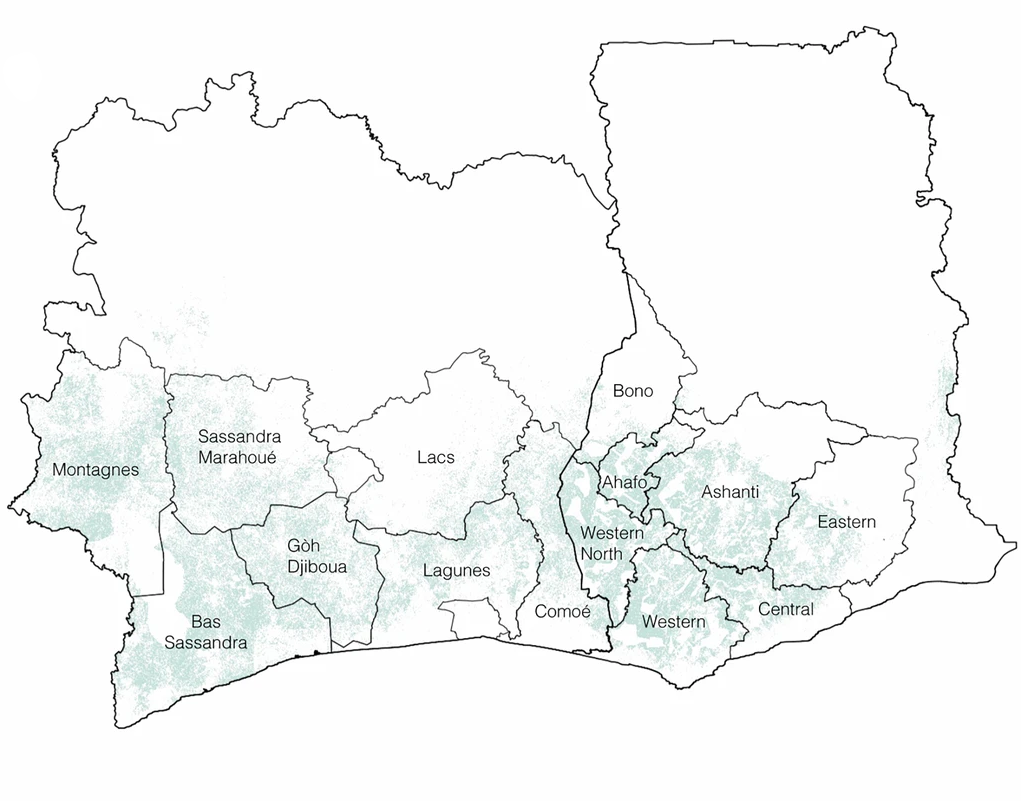

The shading on the map below shows where cocoa is grown in Ivory Coast (left) and Ghana (right).

Both countries have favourable conditions for cocoa production, including tropical forests – which provide nutrients to the soil – a great deal of rain, warm temperatures and low production costs.

Two million farmers in the region rely on cocoa farming for their livelihoods, the study says, and cocoa contributes 10-20% of the two countries’ gross domestic product.

However, cocoa has “one of the most emissions-intensive footprints of all foods”, the study adds.

A 2022 study found that producing 1kg of cacao beans in Ivory Coast releases, on average, 1.5kg of CO2-equivalent (CO2e) – largely a result of deforestation. Since 2000, cocoa plantations have driven 37% of forest loss in protected areas in Ivory Coast and 13% of the loss in protected areas in Ghana.

Cocoa plantations cover more than three-and-a-half times as much land as the remaining intact forests in west Africa, according to the study.

Dr Wilma Blaser Hart, a research fellow at the University of Queensland and an author of the study, tells Carbon Brief:

“That land-use change is what makes cocoa such a carbon-intensive product, because there has just been so much forest loss for being able to produce cocoa.”

Shade-grown cocoa crops

Agroforestry is an agricultural method that combines the planting of crops with trees. Agroforestry can raise incomes for farmers and provide ecosystem services, including soil health improvement, biodiversity conservation and carbon sequestration.

The study investigates the amount of carbon that is currently stored in cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast and Ghana, as well as the potential carbon sequestration if agroforestry were expanded in these countries.

The authors use drones and machine learning to map the cover of shade trees, finding that 13% of the combined area of Ivory Coast and Ghana is currently covered with these trees.

In the study, “shade trees” refers to any trees taller than eight metres – the maximum height of cocoa trees.

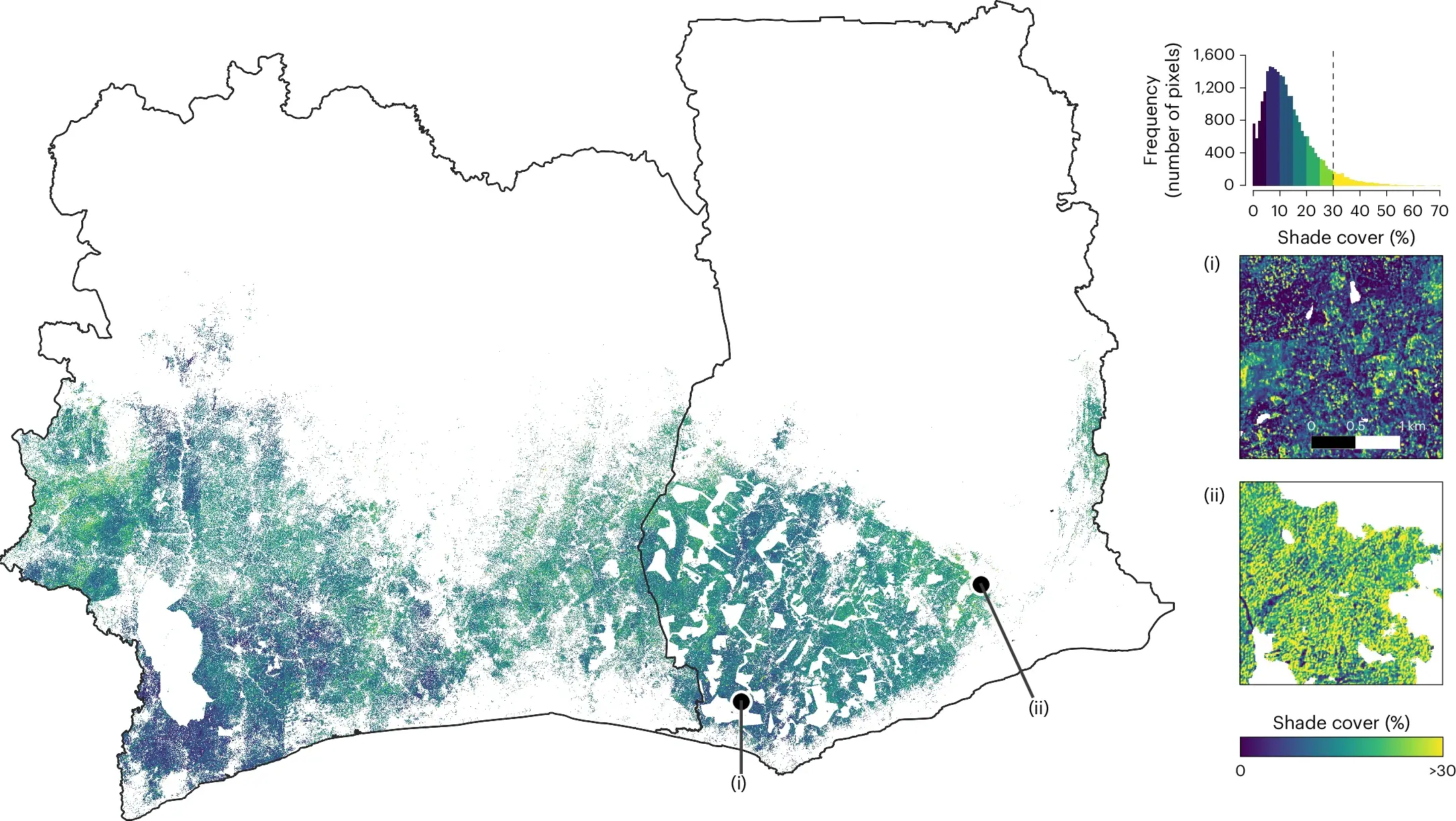

The map below shows the area of shade trees in cocoa-growing areas specifically for 2022. The colours indicate levels of tree cover from 0-15% (blue), through to 15-30% (green) and more than 30% (yellow).

The map reveals that cocoa production is “overwhelmingly dominated by full-sun monocultures and low shade-agroforestry”, the study says.

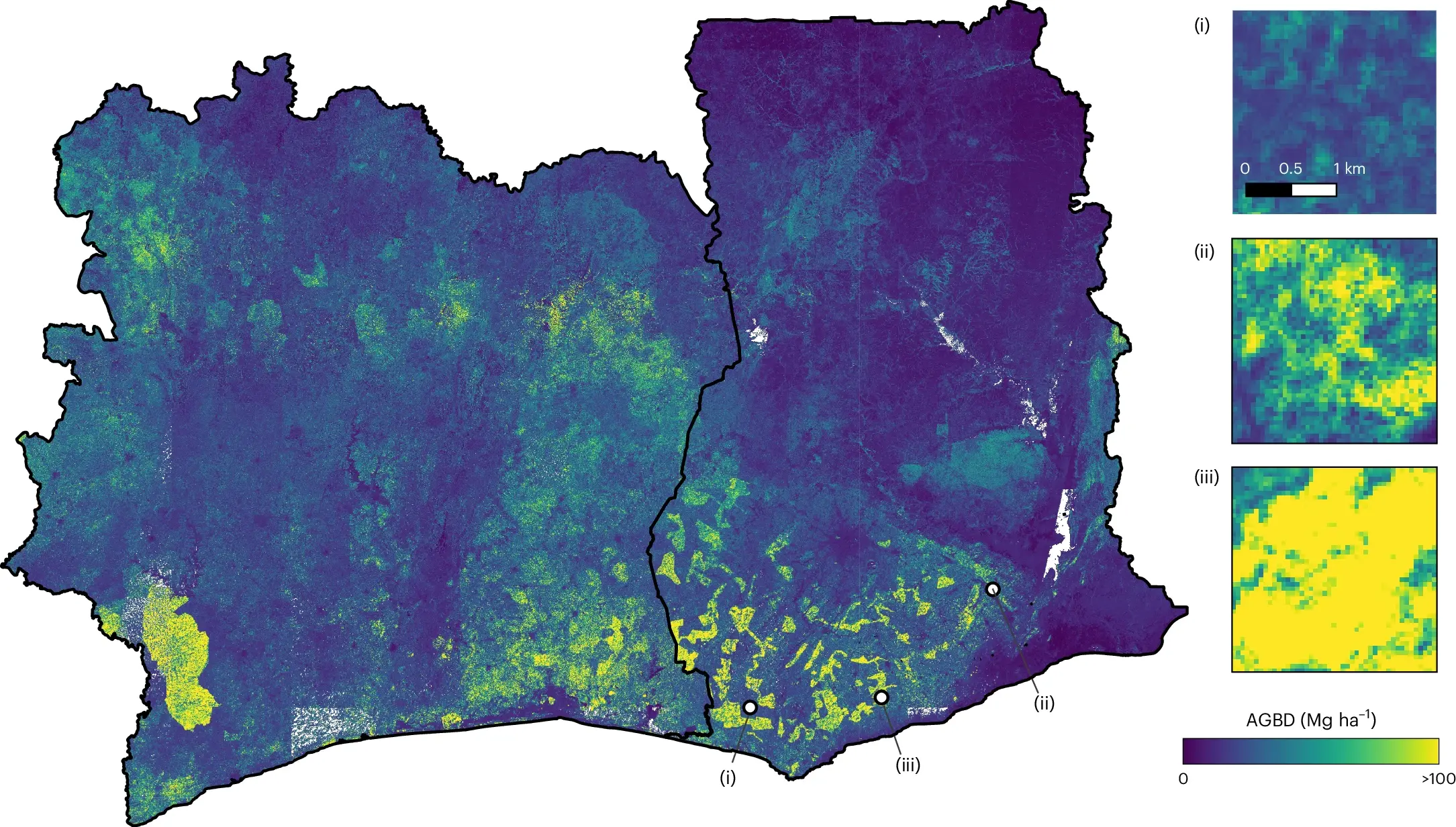

Using satellite data, global maps of tree canopy height and on-ground verification, the researchers map the amount of “aboveground biomass” held by cocoa plantations.

Aboveground biomass comprises all living vegetation that lies above the soil – trees, leaves and other plant matter.

The map below shows the amount of aboveground biomass in both countries. The areas in yellow are those with the highest biomass and, therefore, more stored carbon.

The authors project that if all cocoa plantations increased their cover of shade trees to at least 30%, the additional, taller trees could sequester an “enormous” amount of carbon – 307m tonnes of CO2e (MtCO2e) – enough to fully counterbalance the current cocoa-related emissions in both countries, without reducing production.

Blaser Hart tells Carbon Brief:

“Cocoa itself is a small tree. [It] can grow up to about eight metres tall, so it also sequesters carbon. [But] we found that tall trees that are towering high above cocoa – often timber trees – sequester much more carbon than cocoa.”

In addition, she says, the cover from large trees is “much better for cocoa” since it protects them during the hottest hours of the day, while allowing light through. They also shed large amounts of “litter”, which gets incorporated as organic matter into the soil, sequestering carbon from the atmosphere.

Barriers and limitations

The authors acknowledge several limitations to their study.

For example, they say, the analysis may underestimate the proportion of shade tree cover by excluding trees shorter than eight metres. They also note that the analysis does not consider all of the features of agroforestry systems, such as which species are planted.

Kayeli Laurence is a PhD student of landscape ecology at Jean Lorougnon Guédé University in Ivory Coast and an expert in agroforestry. The researcher, who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief:

“The identified limitations call for caution, particularly when it comes to local, small-scale analyses. However, they do not undermine the general trends highlighted by the study.”

Laurence notes that the study results are consistent with other research highlighting the carbon sequestration potential of agroforestry systems. She says that the projection of carbon sequestration is “ambitious, but credible”. However, she adds:

“In practice, achieving this goal will strongly depend on local conditions: availability of species, technical support, farmers’ willingness and, above all, economic incentives.”

The study also acknowledges that smallholder farmers in west Africa “face several barriers” to adopting agroforestry, including limited incentives and insecure land tenure.

The non-profit scientific research organisation Project Drawdown notes that implementing a certain category of agroforestry called “multistrata” – a combination of long-lasting crops and multiple layers of trees or vegetation – in humid tropical climates would cost more than $1,300 per hectare.

Blaser Hart tells Carbon Brief:

“That’s a huge cost. And it’s not money that farmers have available.”

International landscape

Blaser Hart says that cocoa agroforestry provides further benefits to ecosystems, besides carbon sequestration. These include cooling the air, improving soil fertility and nutrient cycling and providing habitat for wildlife. She adds:

“We’re currently doing a big study on how agroforestry can help to provide habitat for birds. There also seems to be a bit of mammals that use cocoa agroforestry systems. In Ghana, we’re finding quite a bit of genets and civets that are in these systems. From Brazil, there’s a bit of research in the Atlantic Rainforest that shows that some monkeys use them as permanent habitat and others just as corridors to move through.”

Agroforestry is included in the climate commitments of around 40% of developing countries under the Paris Agreement, according to the study.

At the corporate level, the cocoa industry has made commitments to plant “millions of shade trees in agroforests to improve the sustainability of the sector”, the study says.

Blaser Hart tells Carbon Brief that the researchers hope the work will encourage the cocoa industry to better plan its agroforestry interventions, “rather than just haphazardly handing out trees here and there”.

Laurence suggests that policymakers should improve climate finance to support farmers in transitioning to sustainable agricultural systems, while chocolate producers and certification bodies should make stronger commitments to create “real demand for sustainable cocoa produced through agroforestry”.

Ultimately, the study notes that the methods it developed to assess the status of trees in agricultural systems can be used for other commodities grown in agroforests, such as coffee.

The post Growing trees for shade has ‘enormous’ potential for cutting cocoa emissions appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Growing trees for shade has ‘enormous’ potential for cutting cocoa emissions

Greenhouse Gases

Permitting reform: A major key to cutting climate pollution

Permitting reform: A major key to cutting climate pollution

By Dana Nuccitelli, CCL Research Coordinator

Permitting reform has emerged as the biggest and most important clean energy and climate policy area in the 119th Congress (2025-2026).

To make sure every CCL volunteer understands the opportunities and challenges ahead, CCL Vice President of Government Affairs Jennifer Tyler and I recently provided two trainings about the basics of permitting reform and understanding the permitting reform landscape.

These first introductory trainings set the stage for the rest of an ongoing series, which will delve into the details of several key permitting reform topics that CCL is engaging on. Read on for a recap of the first two trainings and a preview of coming attractions.

Permitting reform basics

Before diving into the permitting reform deep end, we need to first understand the fundamentals of the topic: what is “permitting”? What problems are we trying to solve with permitting reform? Why is it a key climate solution?

In short, a permit is a legal authorization issued by a government agency (federal and/or state and/or local) that allows a specific activity or project to proceed under certain defined conditions. The permitting process ensures that public health, safety, and the environment are protected during the construction and operation of the project.

But the permitting process can take a long time, and in some cases it’s taking so long that it’s unduly slowing down the clean energy transition. “Permitting reform” seeks to make the process more efficient while still ensuring that public health, safety, and the environment are protected.

There are a lot of factors involved in the permitting reform process, including environmental laws, limitations on lawsuits, and measures to expedite the building of electrical transmission lines that are key for expanding the capacity of America’s aging electrical grid in order to allow us to connect more clean energy and meet our energy affordability and security and climate needs.

But if we can succeed in passing a good, comprehensive permitting reform package through Congress, it could unlock enough climate pollution reductions to offset what we lost from this year’s rollback of the Inflation Reduction Act’s clean energy investments. Permitting reform is the big climate policy in the current session of Congress.

Understanding the permitting reform landscape

In the second training of this series, we sought to understand the players and the politics in the permitting reform space, learn about the challenges involved, and explore CCL’s framework and approach for weighing in on this policy topic.

Permitting reform has split some traditional alliances along two differing theories about how to best address climate change. Some groups with a theory of change relying on using permitting and lawsuits to slow and stop fossil fuel infrastructure are least likely to be supportive of a permitting reform effort. Groups like CCL that recognize the importance of quickly building lots of clean, affordable energy infrastructure are more supportive of permitting reform measures.

The subject has created some strange bedfellows, because clean energy and fossil fuel companies and organizations all want efficient permitting for their projects, and hence all tend to support permitting reform. For CCL, the key question is whether a comprehensive permitting reform package will be a net benefit to clean energy or the climate — and that’s what we’re working toward.

The two major political parties also have different priorities when it comes to permitting reform. Republicans tend to view it through a lens of reducing government red tape, ensuring that laws and regulations are only used for their intended purpose, and achieving energy affordability and security. Democrats prioritize building clean energy faster to slow climate change, addressing energy affordability, and protecting legacy environmental laws and community engagement.

As we discussed in the training, there are a number of key concepts that will require compromise from both sides of the aisle in order to reach a durable bipartisan permitting reform agreement. We’ll delve into the details of these in these upcoming trainings:

The Challenge of Energy Affordability and Security

First, with support from CCL’s Electrification Action Team, on February 5 I’ll examine what’s behind rising electricity rates and energy insecurity in the U.S. and how we can solve these problems. Electrification is a key climate solution in the transition to clean energy sources. But electricity rates are rising fast and face surging demand from artificial intelligence data centers. Permitting reform can play a key role in addressing these challenges.

Transmission Reform and Key Messages

Insufficient electrical transmission capacity is acting as a bottleneck slowing down the deployment of new clean energy sources in the U.S. Reforming cumbersome transmission permitting processes could unlock billions of tons of avoided climate pollution while improving America’s energy security and affordability. In this training on March 5, Jenn and I will dive into the details of the key clean energy and climate solution that is transmission reform, and the key messages to use when lobbying our members of Congress.

Clean energy projects often encounter long, complex permitting steps that slow construction and raise costs. Practical permitting reforms can help ensure that good projects move forward faster while upholding environmental and community protections. In this training on March 19, Jenn and I will examine permitting reforms to build energy infrastructure faster, some associated tensions and compromises that they may involve, and key messages for congressional offices.

Presidents from both political parties have taken steps to interfere with the permitting of certain types of energy infrastructure that they oppose. These executive actions create uncertainty that inhibits the development of new energy sources in the United States. For this reason, ensuring fair permitting certainty is a key aspect of permitting reform that enjoys bipartisan support. In this training on April 2, Jenn and I will discuss how Congress can ensure certainty in a permitting reform package, and key messages for congressional offices.

Community Engagement and Key Messages

It’s important for energy project developers to engage local communities in order to address any local concerns and adverse impacts that may arise from new infrastructure projects. But it’s also important to strike a careful balance such that community input can be heard and addressed in a timely manner without excessively slowing new clean energy project timelines. In this training on May 7, Jenn and I will examine how community engagement may be addressed in the permitting reform process, and key messages for congressional offices.

We look forward to nerding out with you in these upcoming advanced and important permitting reform trainings!

Want to take action now? Use our online action tool to call Congress and encourage them to work together on comprehensive permitting reform.

The post Permitting reform: A major key to cutting climate pollution appeared first on Citizens' Climate Lobby.

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 30 January 2026: Fire and ice; US formally exits Paris; Climate image faux pas

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Fire and ice

OZ HEAT: The ongoing heatwave in Australia reached record-high temperatures of almost 50C earlier this week, while authorities “urged caution as three forest fires burned out of control”, reported the Associated Press. Bloomberg said the Australian Open tennis tournament “rescheduled matches and activated extreme-heat protocols”. The Guardian reported that “the climate crisis has increased the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, including heatwaves and bushfires”.

WINTER STORM: Meanwhile, a severe winter storm swept across the south and east of the US and parts of Canada, causing “mass power outages and the cancellation of thousands of flights”, reported the Financial Times. More than 870,000 people across the country were without power and at least seven people died, according to BBC News.

COLD QUESTIONED: As the storm approached, climate-sceptic US president Donald Trump took to social media to ask facetiously: “Whatever happened to global warming???”, according to the Associated Press. There is currently significant debate among scientists about whether human-caused climate change is driving record cold extremes, as Carbon Brief has previously explained.

Around the world

- US EXIT: The US has formally left the Paris Agreement for the second time, one year after Trump announced the intention to exit, according to the Guardian. The New York Times reported that the US is “the only country in the world to abandon the international commitment to slow global warming”.

- WEAK PROPOSAL: Trump officials have delayed the repeal of the “endangerment finding” – a legal opinion that underpins federal climate rules in the US – due to “concerns the proposal is too weak to withstand a court challenge”, according to the Washington Post.

- DISCRIMINATION: A court in the Hague has ruled that the Dutch government “discriminated against people in one of its most vulnerable territories” by not helping them to adapt to climate change, reported the Guardian. The court ordered the Dutch government to set binding targets within 18 months to cut greenhouse gas emissions in line with the Paris Agreement, according to the Associated Press.

- WIND PACT: 10 European countries have agreed a “landmark pact” to “accelerate the rollout of offshore windfarms in the 2030s and build a power grid in the North Sea”, according to the Guardian.

- TRADE DEAL: India and the EU have agreed on the “mother of all trade deals”, which will save up to €4bn in import duty, reported the Hindustan Times. Reuters quoted EU officials saying that the landmark trade deal “will not trigger any changes” to the bloc’s carbon border adjustment mechanism.

- ‘TWO-TIER SYSTEM’: COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago believes that global cooperation should move to a “two-speed system, where new coalitions lead fast, practical action alongside the slower, consensus-based decision-making of the UN process”, according to a letter published on Tuesday, reported Climate Home News.

$2.3tn

The amount invested in “green tech” globally in 2025, marking a new record high, according to Bloomberg.

Latest climate research

- Including carbon emissions from permafrost thaw and fires reduces the remaining carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5C by 25% | Communications Earth & Environment

- The global population exposed to extreme heat conditions is projected to nearly double if temperatures reach 2C | Nature Sustainability

- Polar bears in Svalbard – the fastest-warming region on Earth – are in better condition than they were a generation ago, as melting sea ice makes seal pups easier to reach | Scientific Reports

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

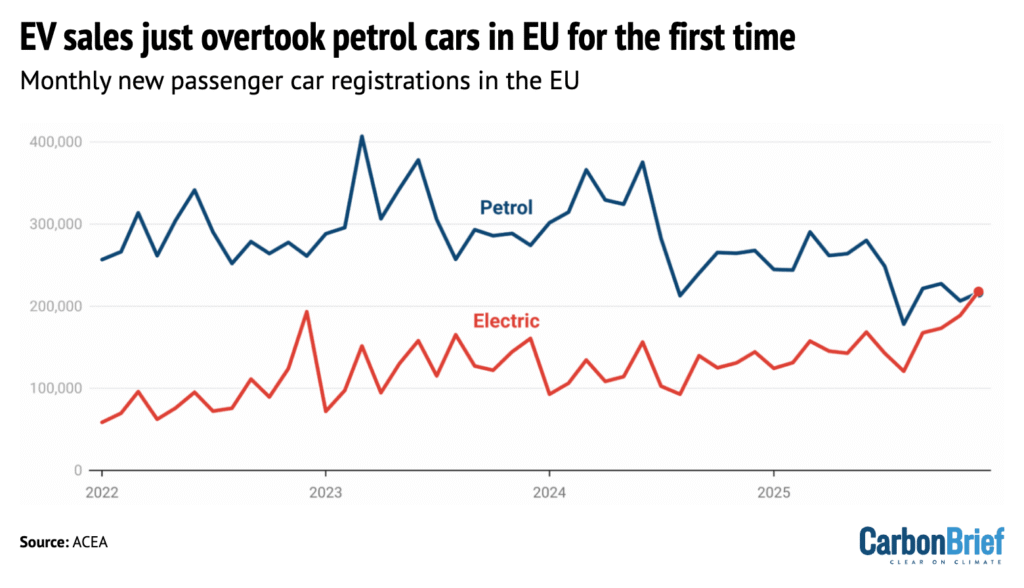

Sales of electric vehicles (EVs) overtook standard petrol cars in the EU for the first time in December 2025, according to new figures released by the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) and covered by Carbon Brief. Registrations of “pure” battery EVs reached 217,898 – up 51% year-on-year from December 2024. Meanwhile, sales of standard petrol cars in the bloc fell 19% year-on-year, from 267,834 in December 2024 to 216,492 in December 2025, according to the analysis.

Spotlight

Looking at climate visuals

Carbon Brief’s Ayesha Tandon recently chaired a panel discussion at the launch of a new book focused on the impact of images used by the media to depict climate change.

When asked to describe an image that represents climate change, many people think of polar bears on melting ice or devastating droughts.

But do these common images – often repeated in the media – risk making climate change feel like a far-away problem from people in the global north? And could they perpetuate harmful stereotypes?

These are some of the questions addressed in a new book by Prof Saffron O’Neill, who researches the visual communication of climate change at the University of Exeter.

“The Visual Life of Climate Change” examines the impact of common images used to depict climate change – and how the use of different visuals might help to effect change.

At a launch event for her book in London, a panel of experts – moderated by Carbon Brief’s Ayesha Tandon – discussed some of the takeaways from the book and the “dos and don’ts” of climate imagery.

Power of an image

“This book is about what kind of work images are doing in the world, who has the power and whose voices are being marginalised,” O’Neill told the gathering of journalists and scientists assembled at the Frontline Club in central London for the launch event.

O’Neill opened by presenting a series of climate imagery case studies from her book. This included several examples of images that could be viewed as “disempowering”.

For example, to visualise climate change in small island nations, such as Tuvalu or Fiji, O’Neill said that photographers often “fly in” to capture images of “small children being vulnerable”. She lamented that this narrative “misses the stories about countries like Tuvalu that are really international leaders in climate policy”.

Similarly, images of power-plant smoke stacks, often used in online climate media articles, almost always omit the people that live alongside them, “breathing their pollution”, she said.

During the panel discussion that followed, panellist Dr James Painter – a research associate at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and senior teaching associate at the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute – highlighted his work on heatwave imagery in the media.

Painter said that “the UK was egregious for its ‘fun in the sun’ imagery” during dangerous heatwaves.

He highlighted a series of images in the Daily Mail in July 2019 depicting people enjoying themselves on beaches or in fountains during an intense heatwave – even as the text of the piece spoke to the negative health impacts of the heatwave.

In contrast, he said his analysis of Indian media revealed “not one single image of ‘fun in the sun’”.

Meanwhile, climate journalist Katherine Dunn asked: “Are we still using and abusing the polar bear?”. O’Neill suggested that polar bear images “are distant in time and space to many people”, but can still be “super engaging” to others – for example, younger audiences.

Panellist Dr Rebecca Swift – senior vice president of creative at Getty images – identified AI-generated images as “the biggest threat that we, in this space, are all having to fight against now”. She expressed concern that we may need to “prove” that images are “actually real”.

However, she argued that AI will not “win” because, “in the end, authentic images, real stories and real people are what we react to”.

When asked if we expect too much from images, O’Neill argued “we can never pin down a social change to one image, but what we can say is that images both shape and reflect the societies that we live in”. She added:

“I don’t think we can ask photos to do the work that we need to do as a society, but they certainly both shape and show us where the future may lie.”

Watch, read, listen

UNSTOPPABLE WILDFIRES: “Funding cuts, conspiracy theories and ‘powder keg’ pine plantations” are making Patagonia’s wildfires “almost impossible to stop”, said the Guardian.

AUDIO SURVEY: Sverige Radio has published “the world’s, probably, longest audio survey” – a six-hour podcast featuring more than 200 people sharing their questions around climate change.

UNDERSTAND CBAM: European thinktank Bruegel released a podcast “all about” the EU’s carbon adjustment border mechanism, which came into force on 1 January.

Coming up

- 1 February: Costa Rican general election

- 3 February: UN Environment Programme Adaptation Fund Climate Innovation Accelerator report launch, Online

- 2-8 February: Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) 12th plenary, Manchester, UK

Pick of the jobs

- Climate Central, climate data scientist | Salary: $85,000-$92,000. Location: Remote (US)

- UN office to the African Union, environmental affairs officer | Salary: Unknown. Location: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- Google Deepmind, research scientist in biosphere models | Salary: Unknown. Location: Zurich, Switzerland

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 30 January 2026: Fire and ice; US formally exits Paris; Climate image faux pas appeared first on Carbon Brief.

DeBriefed 30 January 2026: Fire and ice; US formally exits Paris; Climate image faux pas

Greenhouse Gases

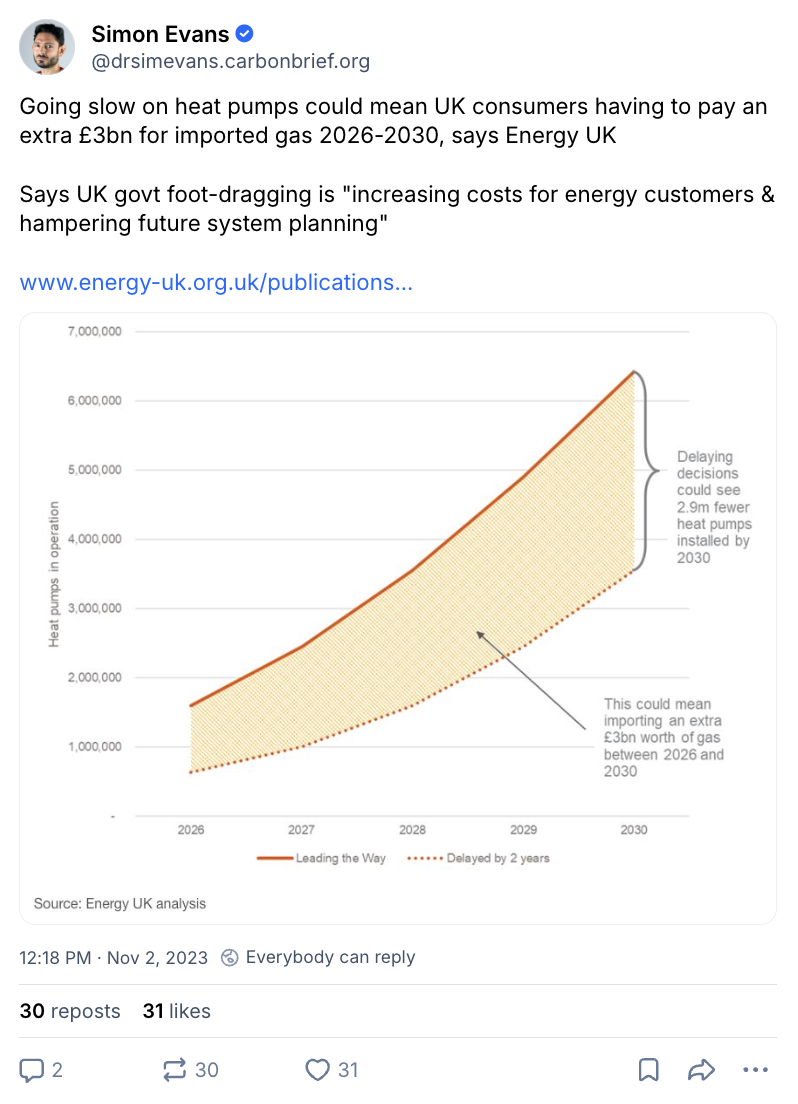

Factcheck: What it really costs to heat a home in the UK with a heat pump

Electric heat pumps are set to play a key role in the UK’s climate strategy, as well as cutting the nation’s reliance on imported fossil fuels.

Heat pumps took centre-stage in the UK government’s recent “warm homes plan”, which said that they could also help cut household energy bills by “hundreds of pounds” a year.

Similarly, innovation agency Nesta estimates that typical households could cut their annual energy bills nearly £300 a year, by switching from a gas boiler to a heat pump.

Yet there has been widespread media coverage in the Times, Sunday Times, Daily Express, Daily Telegraph and elsewhere of a report claiming that heat pumps are “more expensive” to run.

The report is from the Green Britain Foundation set up by Dale Vince, owner of energy firm Ecotricity, who campaigns against heat pumps and invests in “green gas” as an alternative.

One expert tells Carbon Brief that Vince’s report is based on “flimsy data”, while another says that it “combines a series of worst-case assumptions to present an unduly pessimistic picture”.

This factcheck explains how heat pumps can cut bills, what the latest data shows about potential savings and how this information was left out of the report from Vince’s foundation.

How heat pumps can cut bills

Heat pumps use electricity to move heat – most commonly from outside air – to the inside of a building, in a process that is similar to the way that a fridge keeps its contents cold.

This means that they are highly efficient, adding three or four units of heat to the house for each unit of electricity used. In contrast, a gas boiler will always supply less than one unit of heat from each unit of gas that it burns, because some of the energy is lost during combustion.

This means that heat pumps can keep buildings warm while using three, four or even five times less energy than a gas boiler. This cuts fossil-fuel imports, reducing demand for gas by at least two-fifths, even in the unlikely scenario that all of the electricity they need is gas-fired.

Since UK electricity supplies are now the cleanest they have ever been, heat pumps also cut the carbon emissions associated with staying warm by around 85%, relative to a gas boiler.

Heat pumps are, therefore, the “central” technology for cutting carbon emissions from buildings.

While heat pumps cost more to install than gas boilers, the UK government’s recent “warm homes plan” says that they can help cut energy bills by “hundreds of pounds” per year.

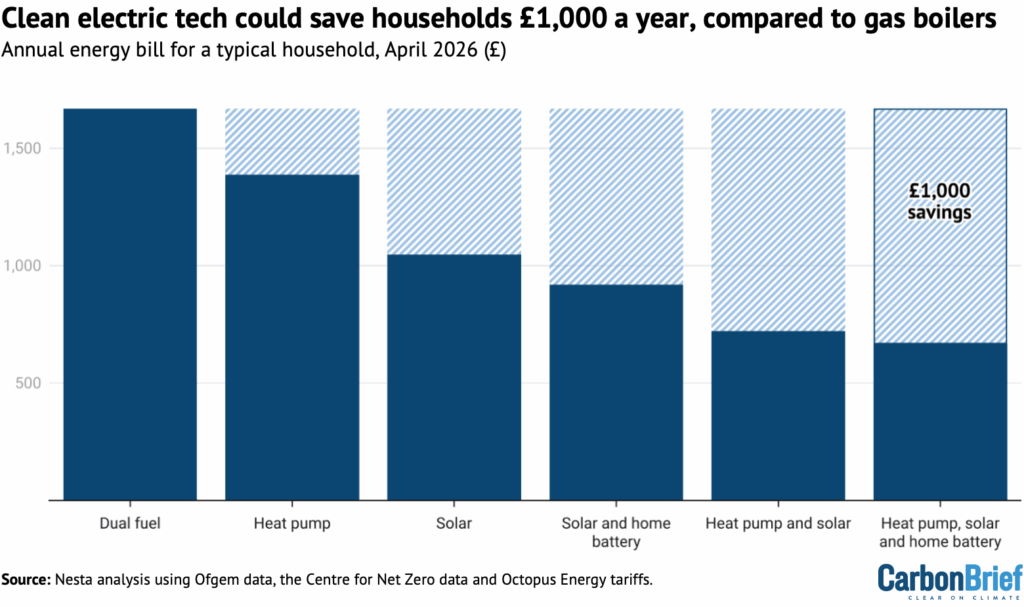

Similarly, Nesta published analysis showing that a typical home could cut its annual energy bill by £280, if it replaces a gas boiler with a heat pump, as shown in the figure below.

Nesta and the government plan say that significantly larger savings are possible if heat pumps are combined with other clean-energy technologies, such as solar and batteries.

Both the government and Nesta’s estimates of bill savings from switching to a heat pump rely on relatively conservative assumptions.

Specifically, the government assumes that a heat pump will deliver 2.8 units of heat for each unit of electricity, on average. This is known as the “seasonal coefficient of performance” (SCoP).

This figure is taken from the government-backed “electrification of heat” trial, which ran during 2020-2022 and showed that heat pumps are suitable for all building types in the UK.

(The Green Britain Foundation report and Vince’s quotes in related coverage repeat a number of heat pump myths, such as the idea that they do not perform well in older properties and require high levels of insulation.)

Nesta assumes a slightly higher SCoP of 3.0, says Madeleine Gabriel, the organisation’s director of sustainable future. (See below for more on what the latest data says about SCoP in recent installations.)

Both the government and Nesta assume that a home with a heat pump would disconnect from the gas grid, meaning that it would no longer need to pay the daily “standing charge” for gas. This currently amounts to a saving of around £130 per year.

Finally, they both consider the impact of a home with a heat pump using a “smart tariff”, where the price of electricity varies according to the time of day.

Such tariffs are now widely available from a variety of energy suppliers and many have been designed specifically for homes that have a heat pump.

Such tariffs significantly reduce the average price for a unit of electricity. Government survey data suggests that around half of heat-pump owners already use such tariffs.

This is important because on the standard rates under the price cap set by energy regulator Ofgem, each unit of electricity costs more than four times as much as a unit of gas.

The ratio between electricity and gas prices is a key determinant of the size and potential for running-cost savings with a heat pump. Countries with a lower electricity-to-gas price ratio consistently see much higher rates of heat-pump adoption.

(Decisions taken by the UK government in its 2025 budget mean that the electricity-to-gas ratio will fall from April, but current forecasts suggest it will remain above four-to-one.)

In contrast, Vince’s report assumes that gas boilers are 90% efficient, whereas data from real homes suggests 85% is more typical. It also assumes that homes with heat pumps remain on the gas grid, paying the standing charge, as well as using only a standard electricity tariff.

Prof Jan Rosenow, energy programme leader at the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute, tells Carbon Brief that Vince’s report uses “worst-case assumptions”. He says:

“This report cherry-picks assumptions to reach a predetermined conclusion. Most notably, it assumes a gas boiler efficiency of 90%, which is significantly higher than real-world performance…Taken together, the analysis combines a series of worst-case assumptions to present an unduly pessimistic picture.”

Similarly, Gabriel tells Carbon Brief that Vince’s report is based on “flimsy data”. She explains:

“Dale Vince has drawn some very strong conclusions about heat pumps from quite flimsy data. Like Dale, we’d also like to see electricity prices come down relative to gas, but we estimate that, from April, even a moderately efficient heat pump on a standard tariff will be cheaper to run than a gas boiler. Paired with a time-of-use tariff, a heat pump could save £280 versus a boiler and adding solar panels and a battery could triple those savings.”

What the latest data shows about bill savings

The efficiency of heat-pump installations is another key factor in the potential bill savings they can deliver and, here, both the government and Vince’s report take a conservative approach.

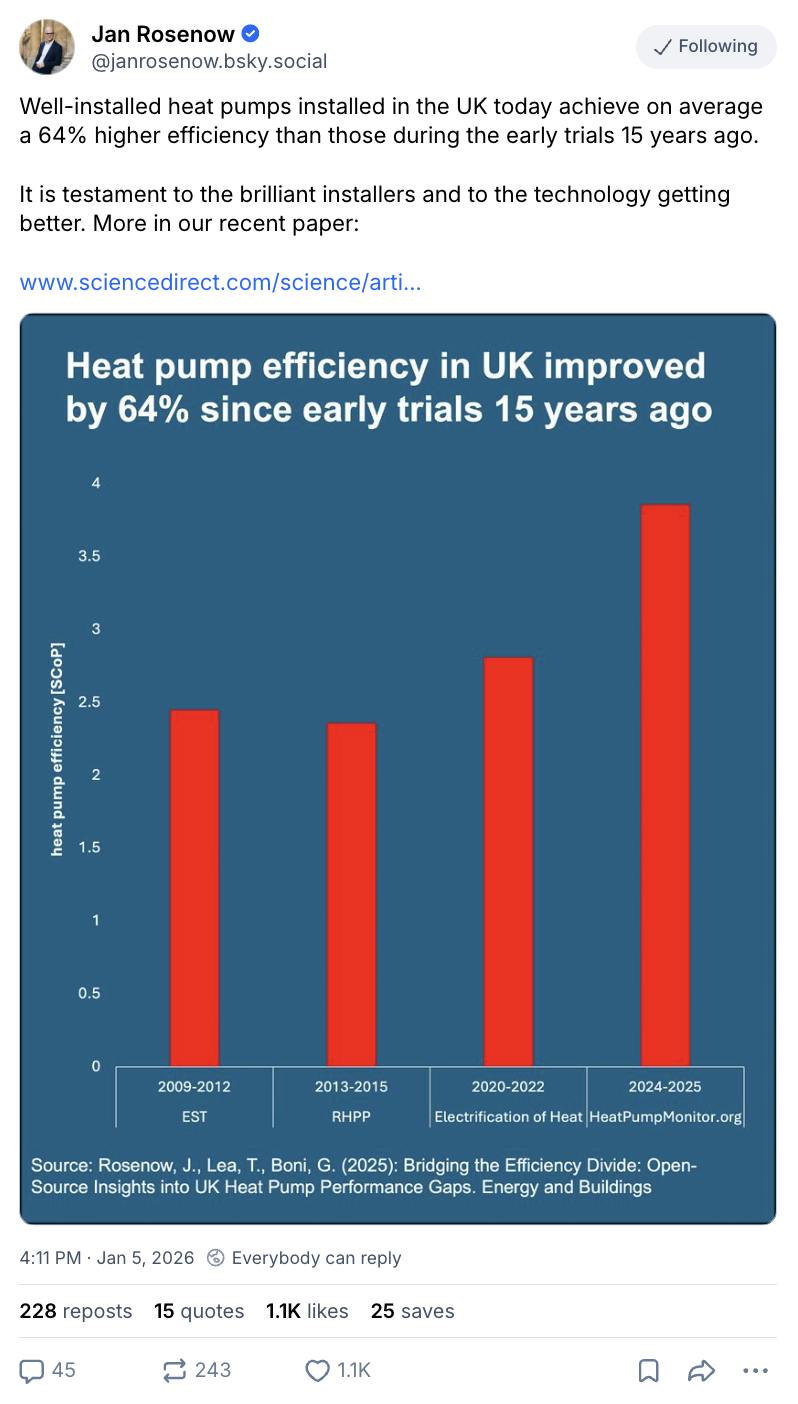

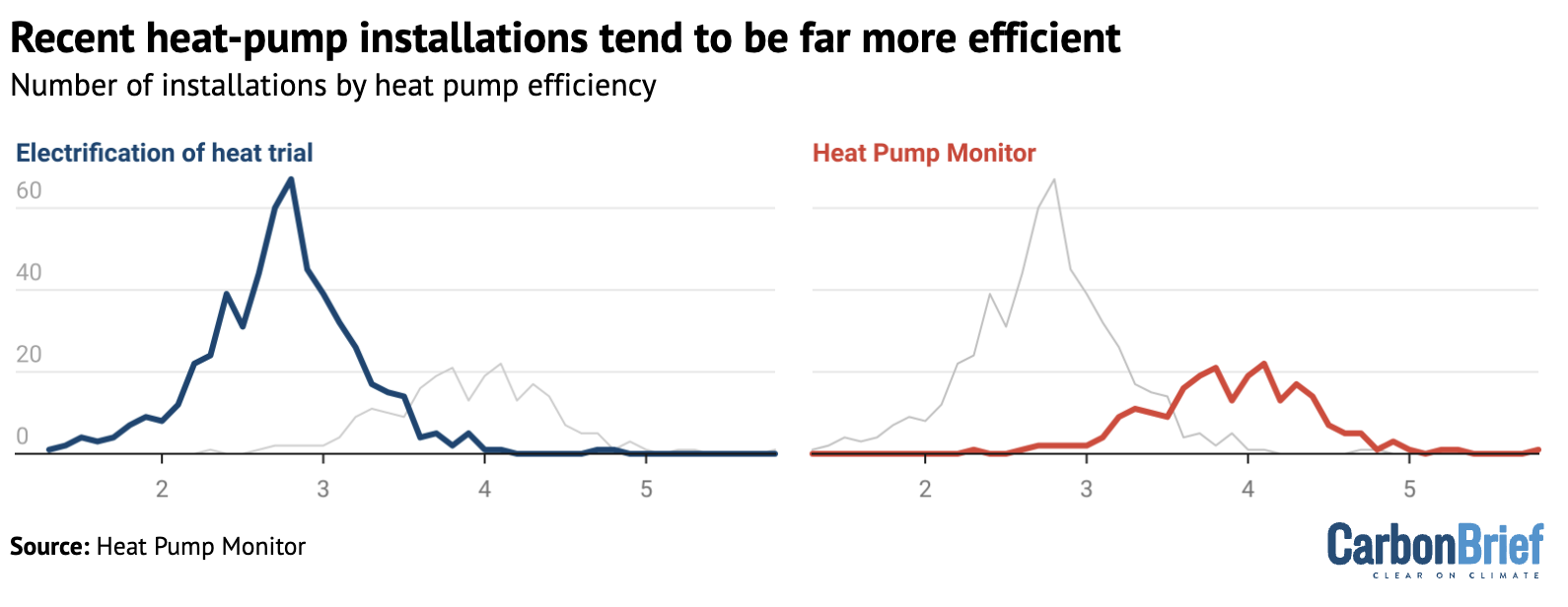

They rely on the “electrification of heat” trial data to use an efficiency (SCoP) of 2.8 for heat pumps. However, Rosenow says that recent evidence shows that “substantially higher efficiencies are routinely available”, as shown in the figure below.

Detailed, real-time data on hundreds of heat pump systems around the UK is available via the website Heat Pump Monitor, where the average efficiency – a SCoP of 3.9 – is much higher.

Homes with such efficient heat-pump installations would see even larger bill savings than suggested by the government and Nesta estimates.

Academic research suggests that there are simple and easy-to-implement reasons why these systems achieve much higher efficiency levels than in the electrification of heat trial.

Specifically, it shows that many of the systems in the trial have poor software settings, which means they do not operate as efficiently as their heat pump hardware is capable of doing.

The research suggests that heat pump installations in the UK have been getting more and more efficient over time, as engineers become increasingly familiar with the technology.

It indicates that recently installed heat pumps are 64% more efficient than those in early trials.

Notably, the Green Britain Foundation report only refers to the trial data from the electrification of heat study carried out in 2020-22 and the even earlier “renewable heat premium package” (RHPP). This makes a huge difference to the estimated running costs of a heat pump.

Carbon Brief analysis suggests that a typical household could cut its annual energy bills by nearly £200 with a heat pump – even on a standard electricity tariff – if the system has a SCoP of 3.9.

The savings would be even larger on a smart heat-pump tariff.

In contrast, based on the oldest efficiency figures mentioned in the Green Britain Foundation report, a heat pump could increase annual household bills by as much as £200 on a standard tariff.

To support its conclusions, the report also includes the results of a survey of 1,001 heat pump owners, which, among other things, is at odds with government survey data. The report says “66% of respondents report that their homes are more expensive to heat than the previous system”.

There are several reasons to treat these findings with caution. The survey was carried out in July 2025 and some 45% of the heat pumps involved were installed between 2021-23.

This is a period during which energy prices surged as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting global energy crisis. Energy bills remain elevated as a result of high gas prices.

The wording of the survey question asks if homes are “more or less expensive to heat than with your previous system” – but makes no mention of these price rises.

The question does not ask homeowners if their bills are higher today, with a heat pump, than they would have been with the household’s previous heating system.

If respondents interpreted the question as asking whether their bills have gone up or down since their heat pump was installed, then their answers will be confounded by the rise in prices overall.

There are a number of other seemingly contradictory aspects of the survey that raise questions about its findings and the strong conclusions in the media coverage of the report.

For example, while only 15% of respondents say it is cheaper to heat their home with a heat pump, 49% say that one of the top three advantages of the system is saving money on energy bills.

In addition, 57% of respondents say they still have a boiler, even though 67% say they received government subsidies for their heat-pump installation. It is a requirement of the government’s boiler upgrade scheme (BUS) grants that homeowners completely remove their boiler.

The government’s own survey of BUS recipients finds that only 13% of respondents say their bills have gone up, whereas 37% say their bills have gone down, another 13% say they have stayed the same and 8% thought that it was too early to say.

The post Factcheck: What it really costs to heat a home in the UK with a heat pump appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Factcheck: What it really costs to heat a home in the UK with a heat pump

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits