The ICYMARE conference in Bremen

Hi, my name is Josephine, I am a student in the Master’s program Biological Oceanography at Geomar Helmholtz-Center for Ocean Research. I am currently writing my Master’s thesis at the Research and Technology Center (FTZ) in Büsum, which is part of Kiel University. My research focuses on the diversity and composition of fish communities in tidal creeks of the German Wadden Sea. My thesis is part of a project that consists of a field survey where fish and benthic communities were sampled at two locations in the Wadden Sea between May and November 2024.

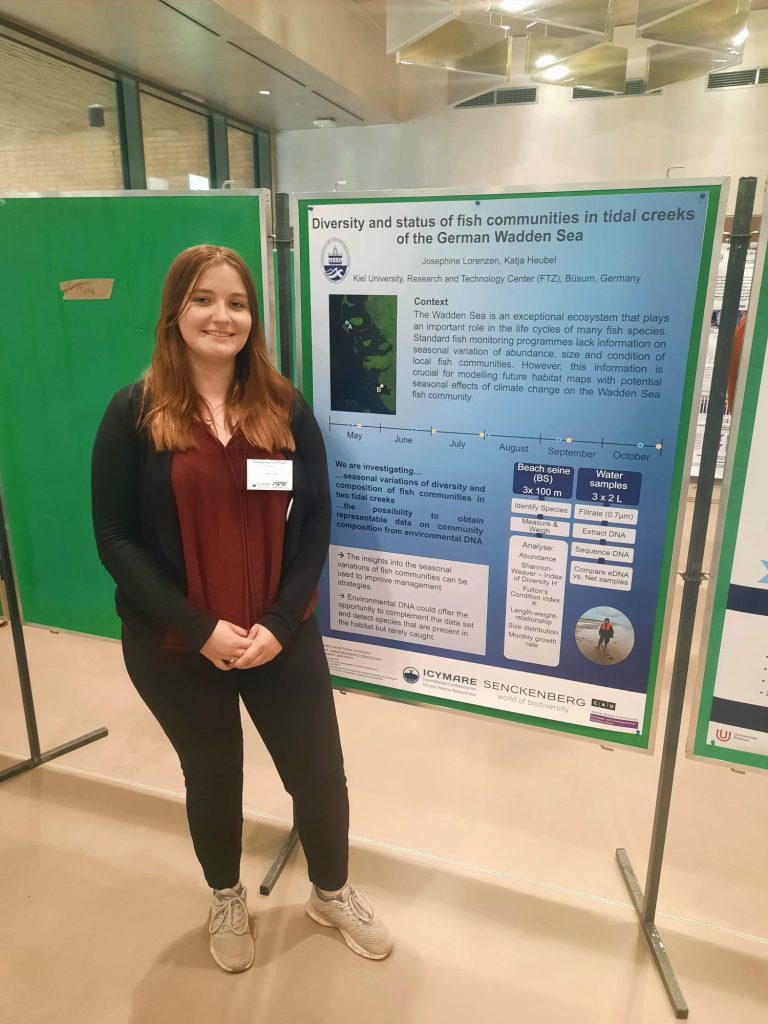

The FYORD travel grant made it possible for me to attend the ICYMARE conference in Bremen, where I presented my research plan in a poster session. The conference took place from September 15th to 20th and generally addresses early career researchers in the field of marine sciences. Most of the participants were PhD students, some recently graduated Postdocs and some master students. The conference started with a get-together for drinks and snacks at the Bremen Overseas Museum and was followed by four days full of interesting talks, a poster session, excursions and ended with a big party. Each day started with a keynote talk held by experienced scientists. What I really enjoyed about this was that most of the talks were interactive and presented a range of career options following a degree in marine sciences. I really had the impression that all these talks were conceptualized to provide guidance, valuable insights and reassurance to young researchers like me. My favorite keynote talk was about merging “Constructive Journalism” and Research for the Greater Good by Christoph Sodemann from the company Constructify.Media, mostly because I have never heard of the concept of “Constructive Journalism”, and I feel like that is exactly what the world needs more of right now. The rest of the day was filled with a variety of presentations, always in two parallel sessions, so that there was always an interesting talk to listen to. There were coffee breaks and a lunch break each day, where you could network or take a look at the posters or enjoy some time in the creative corner, where you could express your passion for marine science and more in little artworks for everyone to see or for you to take home. Every day after lunch, there was a so-called “round table”, where we could hear and talk about topics that are important to us, for example, mental health during a PhD or how to handle conflicts at your workplace.

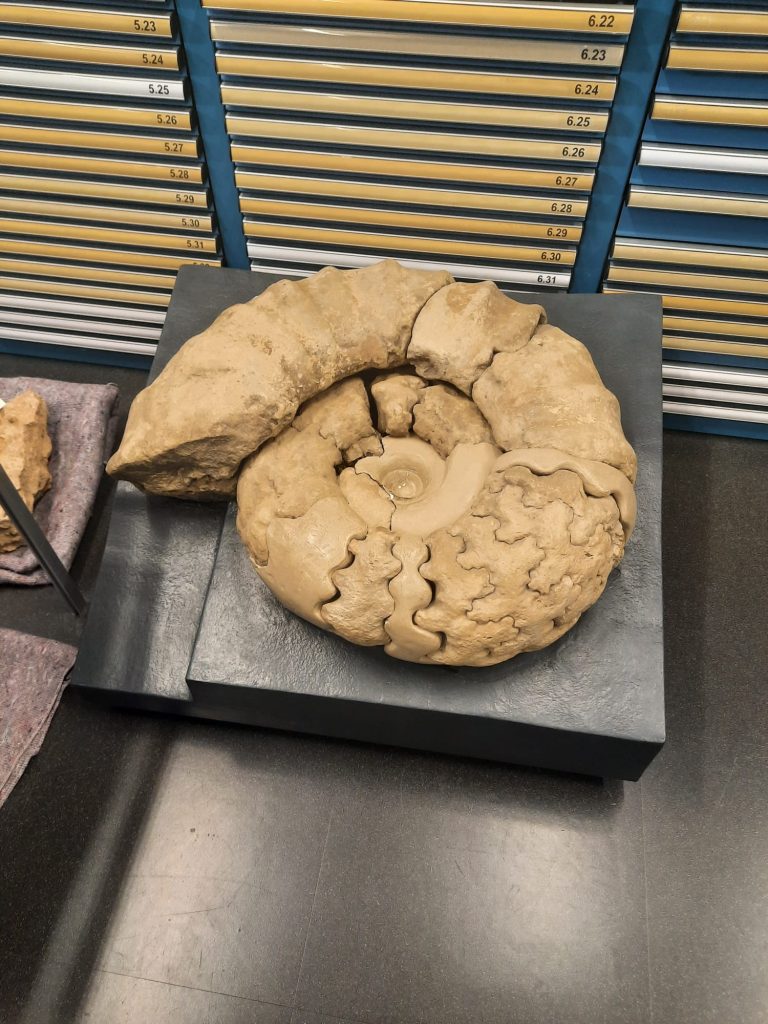

On the second day of the conference, the evening was reserved for the poster session, where I got to present my research for the first time alongside approximately 30 other young scientists. Each presenter was standing next to their poster, ready to answer questions or guide you through the poster. It was a great experience and made me feel more confident about my research. I got to talk to many people, some who work on similar projects, or some who come from a completely different background. This way, I learned how to adjust my presentation to the person who is listening based on what questions they ask. And while it was very exciting, I was also telling the same story over and over again to different people until after two hours of talking, my throat hurt, and I decided to take a look at the other posters and presenters before I headed back to my hostel. The afternoon of the third day was reserved for workshops and excursions. The workshops introduced either technologies, for example for pCO2, pH or acoustic measurements, or aimed to improve skills such as navigating peer review processes or introduced different paths, for example as a data scientist or scientific journalist. I decided to go on one of the excursions that was highly recommended to me, the guided tour through the MARUM, the Bremen core repository of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) and the Geosciences Collection of the University of Bremen. For the evening, a Science Speed Meeting was organized where you could meet other scientists and possibly make some new friends. On Friday evening, the conference was then closed with a Farewell and a Post-Conference Party.

Overall, this was a great experience that increased my confidence in my research and career choice, gave me the opportunity to meet many great people and to gain insights into what is possible after I graduate. What makes this conference so special is that it is mostly organized by young scientists for young scientists, which is reflected in the structure of the conference and the price tag, making it accessible to students. I am definitely going to be in Bremerhaven for the ICYMARE 2025. If you, the reader, are standing at the beginning of your career in marine research, I would highly recommend you come, too.

Josephine Lorenzen

Sea-Level Rise and Vulnerability in Seychelles

My name is Kim Nierobisch. During my studies, I developed a focus on interdisciplinary marine science, completing a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science/Sociology and a Bachelor of Science in Geography, both with a strong emphasis on marine topics. Currently, I am pursuing my Master’s degree in Practical Philosophy of Economy and Environment.

Climate and coastal adaptation planning often operate within a more technical framework, while social, political, cultural, and normative dimensions tend to be sidelined. Beyond the question of who decides where and to what extent adaptation occurs, the normative dimension plays a fundamental role – namely, the essential question of what coastal communities define as worth protecting. My master’s thesis explores the intersection of sea-level rise and vulnerability in Seychelles. Specifically, I analyze how normative values shape coastal adaptation priorities by examining government documents to identify both explicit and implicit strategies. In this context, normative values are understood as collectively held beliefs about what should be prioritized, preserved, or pursued. They reflect societal judgments about what is considered good, just, or desirable. During the workshop, I had the opportunity to reflect on these findings. As part of a focus group discussion, I explored the normative dimension of coastal adaptation priorities more deeply, allowing me to better understand and contextualize normative values, which resonate in decision-making but remain underexamined.

The workshop on Sea-Level Rise Impacts in Seychelles 2024 was organized by the adjust team from Kiel University, the Ministry of Agriculture, Climate Change and Environment (Seychelles), and Sustainability for Seychelles. It brought together stakeholders mainly representing government organizations, environmental consultants, and nature conservation groups. The workshop combined inter- and transdisciplinary approaches to analyze the impacts of sea-level rise in Seychelles, assess coastal adaptation options, and discuss various strategies and priorities.

The process of analyzing and extracting normative values was quite challenging. Although normative values were not explicitly named or fully recognized within a technical dominant framework, they were clearly present and influenced coastal adaptation planning. This underscores the importance of more deeply integrating social, political, cultural, and normative dimensions into research and planning processes. Inter- and transdisciplinary formats have their limits (which should always be defined), but they remain valuable approaches because they provide a more holistic understanding of complex issues. A key takeaway from my experience was understanding that such collaboration requires continuous dialogue and exchange to overcome barriers between different perspectives. It takes a lot of time, effort, and persistence, especially due to the different epistemologies – different ways of knowing and understanding the world, which are shaped by different disciplines, cultures, and experiences – involved.

Additionally, I had the opportunity to strengthen dialogue and cooperation within the UN Ocean Decade framework. The initiative was officially endorsed as an UN Ocean Decade activity, focusing on research and planning that promotes sustainable ocean governance through interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and integrative approaches. As the youngest member of the German UN Ocean Decade Committee, I recognize the urgency of addressing current challenges, such as the 1.5°C target (which is at risk of failing) and the limited progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (with only around 16% expected to be achieved by 2030). Dialogue, particularly among young ocean enthusiasts and early career ocean professionals, is necessary to tackle these challenges and build a sustainable future together. These conversations offered an important opportunity to promote solidarity, mutual support, and shared motivation in a time of uncertainty regarding global climate and ocean-related goals.

THANK YOU! I am deeply grateful for the many meaningful encounters with incredible people, inspiring moments, and the fruitful, critical exchanges that took place in Seychelles. I would like to sincerely thank the FYORD team and the OceanVoices blog for their long-standing support and collaboration.

Kim Nierobisch

The ASLO Aquatic Sciences Meeting

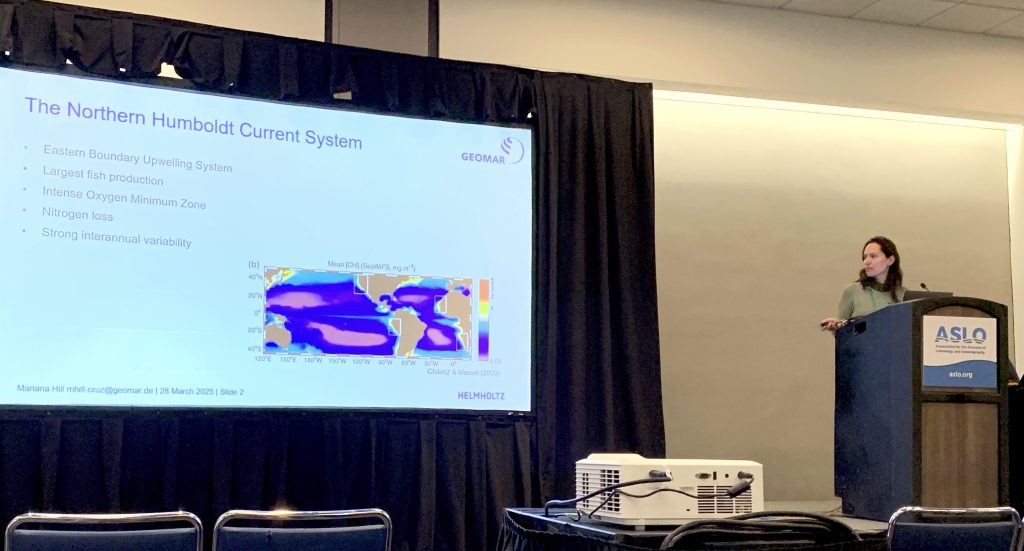

My name is Mariana Hill, and I work at the Biogeochemical Modelling group at GEOMAR. I’ve been at GEOMAR since 2016, when I started my Master’s degree. Currently, I do my own research in collaboration with other members of GEOMAR and institutes overseas. I am interested in modelling higher trophic levels, such as fish, sharks and whales, and their interactions with the environment. For this, I use diverse tools, for example, dynamic models such as the individual-based multispecies model OSMOSE, as well as habitat niche models using statistical and machine learning algorithms. I work with regional models, allowing me to study in detail local ecosystems. For my doctorate, I focused on the northern Humboldt Current System, which hosts the most productive fishery on the planet. During the postdoc, I have expanded my expertise to other ecosystems such as the western Baltic Sea, the North Atlantic Ocean and the Mexican Pacific.

I attended the ASLO Aquatic Sciences Meeting in Charlotte, USA, from the 26th to the 31st of March. I presented our latest work modelling the habitat of Peruvian anchovies in the northern Humboldt Current System. This conference gathers every two years researchers working on ocean sciences and limnology from all over the world. While there’s room in the conference for scientists working in all kinds of aquatic fields, biogeochemistry and marine biology are especially well covered. I presented at the “Leveraging Modelling Approaches to Understand and Mitigate Global Change Impacts on Aquatic Ecosystems” session, which was one of the largest in the conference, spanning a whole day. This session brought together modellers from several disciplines, so I got the chance to learn about new ecological models that I had not heard of, such as the structural casual models. I was also impressed by the level of expertise of some really young scientists, even in their Bachelor’s. I found it an interesting experience that, despite being an early career scientist, in this conference, I took more of a mentoring role for younger scientists in contrast to my previous conferences when I was still a student.

The ASLO conference is very friendly with students and early career researchers, providing plenty of opportunities for these groups, such as workshops on science communication and career development, social events, mentoring and even a mailing list for searching for shared accommodation. I got the chance to reconnect with another Master’s student from GEOMAR who is now working as a postdoc in Arizona and went for a hike in the Appalachian Mountains with some of her friends. The whole experience ended up with being invited to a new working group on Nitrogen. Another non-conventional exchange happened at the parking lot of our accommodation when everyone had to evacuate due to a false fire alarm, and my roommate and I met a senior scientist working in Texas who reminded us of the most basic questions of why we do science. Don’t just write proposals on the hot topics, “do what you love and your time will come”.

ASLO 2019 was the first conference that I attended when I started my doctorate. Back then, I found the possibility of chairing a session at a future conference attractive. Later on, I learnt that this is not such an easy task since you have to look for co-hosts and write a session proposal. However, this year, when I got my letter of acceptance to present at ASLO, I also got an invitation to chair one of the sessions that had been proposed by the organisers but did not have a host yet. I expressed my interest and became the chair of the “Fish and Fisheries” session! This was a very rewarding experience since I got to know the speakers of the session, as well as my co-chair, and I learnt what it is to be “on the other side of the table” during a session. I learnt some useful practices that I will apply from now on whenever I present at a conference session. For example, something I did not use to do but now I consider important is to introduce yourself to the session chair before the session starts. As a chair, I really appreciated this since I could identify the speakers and know if anyone was missing.

Keep an open mind when going to ASLO and step out of your comfort zone to visit not only the sessions related to your main research interest but also other sessions and workshops; you might get nice surprises. It is also a great setting for getting career advice from people who are not so close to you or are not involved in your work. Don’t be scared of talking to senior researchers, I have never encountered a person who is not happy to talk to me during a conference; in the worst-case scenario, you might just need to line up for a couple of minutes, but the time spent waiting is totally worth it! I have got some of the best ideas for my science communication strategies at conferences, from a scientist who was not very comfortable speaking English bringing a buffet of questions about his talk for the audience to pick from, to an improv workshop on how to speak freely and engage with the audience through a positive attitude hosted by a Hollywood actor. Always have a notebook for taking notes with you because your brain will be boiling with new ideas during the whole conference.

I recommend attending the ASLO conference, especially to early career researchers, to biologists and biogeochemists and to anyone looking for collaborations in the USA. A special recommendation for shy scientists is to try different ways of networking, not just the typical chats during the coffee breaks. For example, the icebreakers and mixers usually have specific formats to integrate everyone into small groups. Talking to the person sitting next to you during the plenary session might just get you to meet a top scientist in your field. This is how I got to know about a new project on whale monitoring in the Virgin Islands! Furthermore, asking questions one-to-one to the presenter after the session or plenary is also a great way to start a conversation. And, finally, I totally recommend any early career scientist to host a session; it is a lot of fun and, at least in ASLO, the format is so friendly that it will cost you barely any effort.

Mariana Hill

Ocean Acidification

What is the High Seas Treaty and Why Does It Matter?

You may have seen headlines recently about a new global treaty that went into effect just as news broke that the United States would be withdrawing from a number of other international agreements. It’s a confusing time in the world of environmental policy, and Ocean Conservancy is here to help make it clearer while, of course, continuing to protect our ocean.

What is the High Seas Treaty?

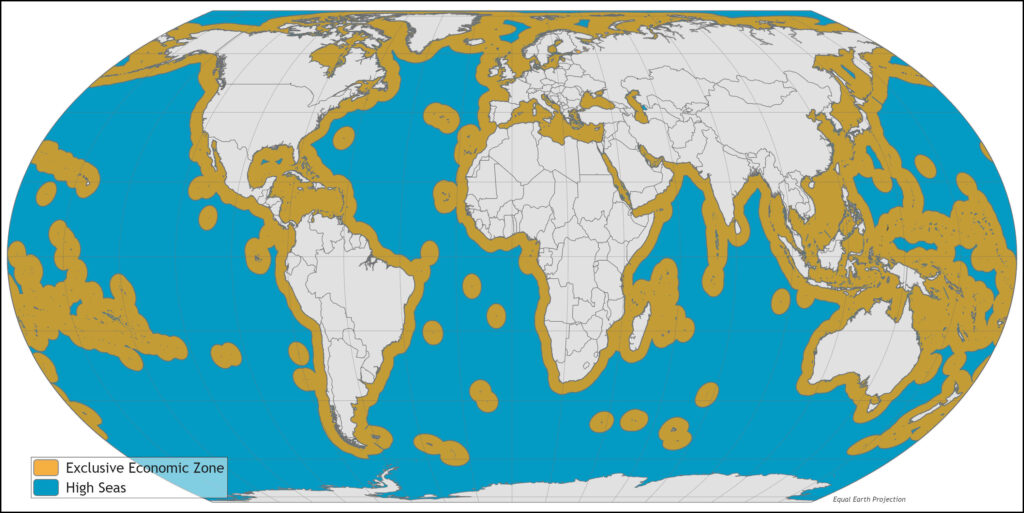

The “High Seas Treaty,” formally known as the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement, went into effect on January 17, 2026. We celebrated this win last fall, when the agreement reached the 60 ratifications required for its entry into force. (Since then, an additional 23 countries have joined!) It is the first comprehensive international legal framework dedicated to addressing the conservation and sustainable use of the high seas (the area of the ocean that lies 200 miles beyond the shorelines of individual countries).

To “ensure the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity” of these areas, the BBNJ addresses four core pillars of ocean governance:

- Marine genetic resources: The high seas contain genetic resources (genes of plants, animals and microbes) of great value for pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and food production. The treaty will ensure benefits accrued from the development of these resources are shared equitably amongst nations.

- Area-based management tools such as the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) in international waters. Protecting important areas of the ocean is essential for healthy and resilient ecosystems and marine biodiversity.

- Environmental impact assessments (EIA) will allow us to better understand the potential impacts of proposed activities that may harm the ocean so that they can be managed appropriately.

- Capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology with particular emphasis on supporting developing states. This section of the treaty is designed to ensure all nations benefit from the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity through, for example, the sharing of scientific information.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

Why is the High Seas Treaty Important?

The BBNJ agreement is legally binding for the countries that have ratified it and is the culmination of nearly two decades of negotiations. Its enactment is a historic milestone for global ocean governance and a significant advancement in the collective protection of marine ecosystems.

The high seas represent about two-thirds of the global ocean, and yet less than 10% of this area is currently protected. This has meant that the high seas have been vulnerable to unregulated or illegal fishing activities and unregulated waste disposal. Recognizing a major governance gap for nearly half of the planet, the agreement puts in place a legal framework to conserve biodiversity.

As it promotes strengthened international cooperation and accountability, the agreement will establish safeguards aimed at preventing and reversing ocean degradation and promoting ecosystem restoration. Furthermore, it will mobilize the international community to develop new legal, scientific, financial and compliance mechanisms, while reinforcing coordination among existing treaties, institutions and organizations to address long-standing governance gaps.

How is Ocean Conservancy Supporting the BBNJ Agreement?

Addressing the global biodiversity crisis is a key focal area for Ocean Conservancy, and the BBNJ agreement adds important new tools to the marine conservation toolbox and a global commitment to better protect the ocean.

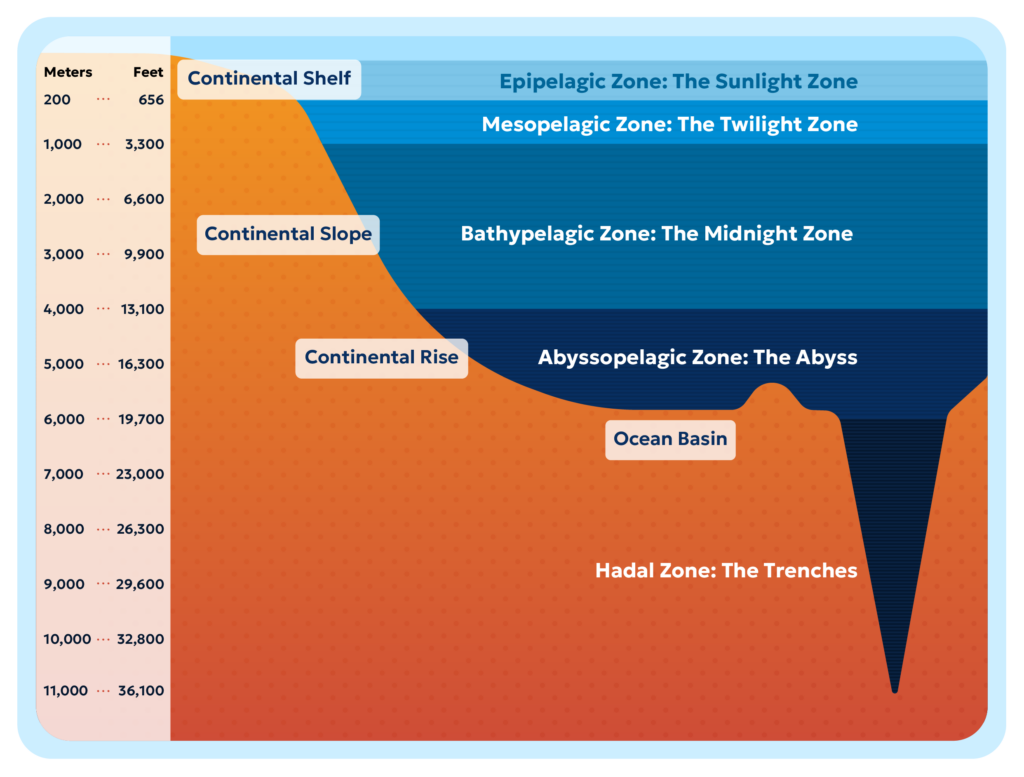

Ocean Conservancy’s efforts to protect the “ocean twilight zone”—an area of the ocean 200-1000m (600-3000 ft) below the surface—is a good example of why the BBNJ agreement is so important. The ocean twilight zone (also known as the mesopelagic zone) harbors incredible marine biodiversity, regulates the climate and supports the health of ocean ecosystems. By some estimates, more than 90% of the fish biomass in the ocean resides in the ocean twilight zone, attracting the interest of those eager to develop new sources of protein for use in aquaculture feed and pet foods.

Done poorly, such development could have major ramifications for the health of our planet, jeopardizing the critical role these species play in regulating the planet’s climate and sustaining commercially and ecologically significant marine species. Species such as tunas (the world’s most valuable fishery), swordfish, salmon, sharks and whales depend upon mesopelagic species as a source of food. Mesopelagic organisms would also be vulnerable to other proposed activities including deep-sea mining.

A significant portion of the ocean twilight zone is in the high seas, and science and policy experts have identified key gaps in ocean governance that make this area particularly vulnerable to future exploitation. The BBNJ agreement’s provisions to assess the impacts of new activities on the high seas before exploitation begins (via EIAs) as well as the ability to proactively protect this area can help ensure the important services the ocean twilight zone provides to our planet continue well into the future.

What’s Next?

Notably, the United States has not ratified the treaty, and, in fact, just a few days before it went into effect, the United States announced its withdrawal from several important international forums, including many focused on the environment. While we at Ocean Conservancy were disappointed by this announcement, there is no doubt that the work will continue.

With the agreement now in force, the first Conference of the Parties (COP1), also referred to as the BBNJ COP, will convene within the next year and will play a critical role in finalizing implementation, compliance and operational details under the agreement. Ocean Conservancy will work with partners to ensure implementation of the agreement is up to the challenge of the global biodiversity crisis.

The post What is the High Seas Treaty and Why Does It Matter? appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2026/02/25/high-seas-treaty/

Ocean Acidification

Hälsningar från Åland och Husö biological station

On Åland, the seasons change quickly and vividly. In summer, the nights never really grow dark as the sun hovers just below the horizon. Only a few months later, autumn creeps in and softly cloaks the island in darkness again. The rhythm of the seasons is mirrored by the biological station itself; researchers, professors, and students arrive and depart, bringing with them microscopes, incubators, mesocosms, and field gear to study the local flora and fauna peaking in the mid of summer.

This year’s GAME project is the final chapter of a series of studies on light pollution. Together, we, Pauline & Linus, are studying the effects of artificial light at night (ALAN) on epiphytic filamentous algae. Like the GAME site in Japan, Akkeshi, the biological station Husö here on Åland experiences very little light pollution, making it an ideal place to investigate this subject.

We started our journey at the end of April 2025, just as the islands were waking up from winter. The trees were still bare, the mornings frosty, and the streets quiet. Pauline, a Marine Biology Master’s student from the University of Algarve in Portugal, arrived first and was welcomed by Tony Cederberg, the station manager. Spending the first night alone on the station was unique before the bustle of the project began.

Linus, a Marine Biology Master’s student at Åbo Akademi University in Finland, joined the next day. Husö is the university’s field station and therefore Linus has been here for courses already. However, he was excited to spend a longer stretch at the station and to make the place feel like a second home.

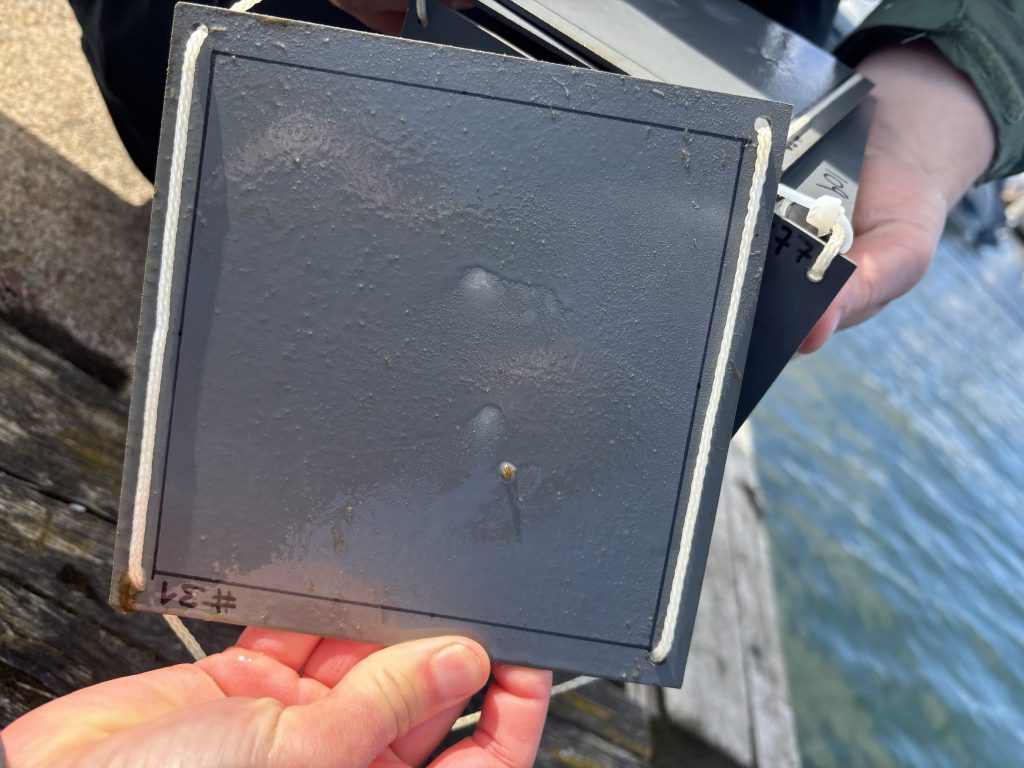

Our first days were spent digging through cupboards and sheds, reusing old materials and tools from previous years, and preparing the frames used by GAME 2023. We chose Hamnsundet as our experimental site, (i.e. the same site that was used for GAME 2023), which is located at the northeast of Åland on the outer archipelago roughly 40 km from Husö. We got permission to deploy the experiments by the local coast guard station, which was perfect. The location is sheltered from strong winds, has electricity access, can be reached by car, and provides the salinity conditions needed for our macroalga, Fucus vesiculosus, to survive.

To assess the conditions at the experimental site, we deployed a first set of settlement panels in late April. At first, colonization was slow; only a faint biofilm appeared within two weeks. With the water temperature being still around 7 °C, we decided to give nature more time. Meanwhile, we collected Fucus individuals and practiced the cleaning and the standardizing of the algal thalli for the experiment. Scraping epiphytes off each thallus piece was fiddly, and agreeing on one method was crucial to make sure our results would be comparable to those of other GAME teams.

By early May, building the light setup was a project in itself. Sawing, drilling, testing LEDs, and learning how to secure a 5-meter wooden beam over the water. Our first version bent and twisted until the light pointed sideways instead of straight down onto the algae. Only after buying thicker beams and rebuilding the structure, we finally got a stable and functional setup that could withstand heavy rain and wind. The day we deployed our first experiment at Hamnsundet was cold and rainy but also very rewarding!

Outside of work, we made the most of the island life. We explored Åland by bike, kayak, rowboat, and hiking, visited Ramsholmen National Park during the ramson/ wild garlic bloom, and hiked in Geta with its impressive rock formations and went out boating and fishing in the archipelago. At the station on Husö, cooking became a social event: baking sourdough bread, turning rhubarb from the garden into pies, grilling and making all kind of mushroom dishes. These breaks, in the kitchen and in nature, helped us recharge for the long lab sessions to come.

Every two weeks, it was time to collect and process samples. Snorkeling to the frames, cutting the Fucus and the PVC plates from the lines, and transferring each piece into a freezer bag became our routine. Sampling one experiment took us 4 days and processing all the replicates in the lab easily filled an entire week. The filtering and scraping process was even more time-consuming than we had imagined. It turned out that epiphyte soup is quite thick and clogs filters fastly. This was frustrating at times, since it slowed us down massively.

Over the months, the general community in the water changed drastically. In June, water was still at 10 °C, Fucus carried only a thin layer of diatoms and some very persistent and hard too scrape brown algae (Elachista). In July, everything suddenly exploded: green algae, brown algae, diatoms, cyanobacteria, and tiny zooplankton clogged our filters. With a doubled filtering setup and 6 filtering units, we hoped to compensate for the additional growth.

However, what we had planned as “moderate lab days” turned into marathon sessions. In August, at nearly 20 °C, the Fucus was looking surprisingly clean, but on the PVC a clear winner had emerged. The panels were overrun with the green alga Ulva and looked like the lawn at an abandoned house. Here it was not enough to simply filter the solution, but bigger pieces had to be dried separately. In September, we concluded the last experiment with the help of Sarah from the Cape Verde team, as it was not possible for her to continue on São Vicente, the Cape Verdean island that was most affected by a tropical storm. Our final experiment brought yet another change into community now dominated by brown algae and diatoms. Thankfully our new recruit, sunny autumn weather, and mushroom picking on the side made the last push enjoyable.

By the end of summer, we had accomplished four full experiments. The days were sometimes exhausting but also incredibly rewarding. We learned not only about the ecological effects of artificial light at night, but also about the very practical side of marine research; planning, troubleshooting, and the patience it takes when filtering a few samples can occupy half a day.

Ocean Acidification

What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs?

Coral reefs are beautiful, vibrant ecosystems and a cornerstone of a healthy ocean. Often called the “rainforests of the sea,” they support an extraordinary diversity of marine life from fish and crustaceans to mollusks, sea turtles and more. Although reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean floor, they provide critical habitat for roughly 25% of all ocean species.

Coral reefs are also essential to human wellbeing. These structures reduce the force of waves before they reach shore, providing communities with vital protection from extreme weather such as hurricanes and cyclones. It is estimated that reefs safeguard hundreds of millions of people in more than 100 countries.

What is coral bleaching?

A key component of coral reefs are coral polyps—tiny soft bodied animals related to jellyfish and anemones. What we think of as coral reefs are actually colonies of hundreds to thousands of individual polyps. In hard corals, these tiny animals produce a rigid skeleton made of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). The calcium carbonate provides a hard outer structure that protects the soft parts of the coral. These hard corals are the primary building blocks of coral reefs, unlike their soft coral relatives that don’t secrete any calcium carbonate.

Coral reefs get their bright colors from tiny algae called zooxanthellae. The coral polyps themselves are transparent, and they depend on zooxanthellae for food. In return, the coral polyp provides the zooxanethellae with shelter and protection, a symbiotic relationship that keeps the greater reefs healthy and thriving.

When corals experience stress, like pollution and ocean warming, they can expel their zooxanthellae. Without the zooxanthellae, corals lose their color and turn white, a process known as coral bleaching. If bleaching continues for too long, the coral reef can starve and die.

Ocean warming and coral bleaching

Human-driven stressors, especially ocean warming, threaten the long-term survival of coral reefs. An alarming 77% of the world’s reef areas are already affected by bleaching-level heat stress.

The Great Barrier Reef is a stark example of the catastrophic impacts of coral bleaching. The Great Barrier Reef is made up of 3,000 reefs and is home to thousands of species of marine life. In 2025, the Great Barrier Reef experienced its sixth mass bleaching since 2016. It should also be noted that coral bleaching events are a new thing because of ocean warming, with the first documented in 1998.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

How you can help

The planet is changing rapidly, and the stakes have never been higher. The ocean has absorbed roughly 90% of the excess heat caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, and the consequences, including coral die-offs, are already visible. With just 2℃ of planetary warming, global coral reef losses are estimated to be up to 99% — and without significant change, the world is on track for 2.8°C of warming by century’s end.

To stop coral bleaching, we need to address the climate crisis head on. A recent study from Scripps Institution of Oceanography was the first of its kind to include damage to ocean ecosystems into the economic cost of climate change – resulting in nearly a doubling in the social cost of carbon. This is the first time the ocean was considered in terms of economic harm caused by greenhouse gas emissions, despite the widespread degradation to ocean ecosystems like coral reefs and the millions of people impacted globally.

This is why Ocean Conservancy advocates for phasing out harmful offshore oil and gas and transitioning to clean ocean energy. In this endeavor, Ocean Conservancy also leads international efforts to eliminate emissions from the global shipping industry—responsible for roughly 1 billion tons of carbon dioxide every year.

But we cannot do this work without your help. We need leaders at every level to recognize that the ocean must be part of the solution to the climate crisis. Reach out to your elected officials and demand ocean-climate action now.

The post What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs? appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs?

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits