As temperature records are shattered, ice rapidly melts and extreme weather events worsen, many people around the world say they are feeling more worried about climate change.

Researchers call this growing phenomenon “climate anxiety”.

A new analysis examines 94 studies focused on climate anxiety, involving 170,000 people across 27 countries, to explore who it is most likely to affect and what its possible consequences could be.

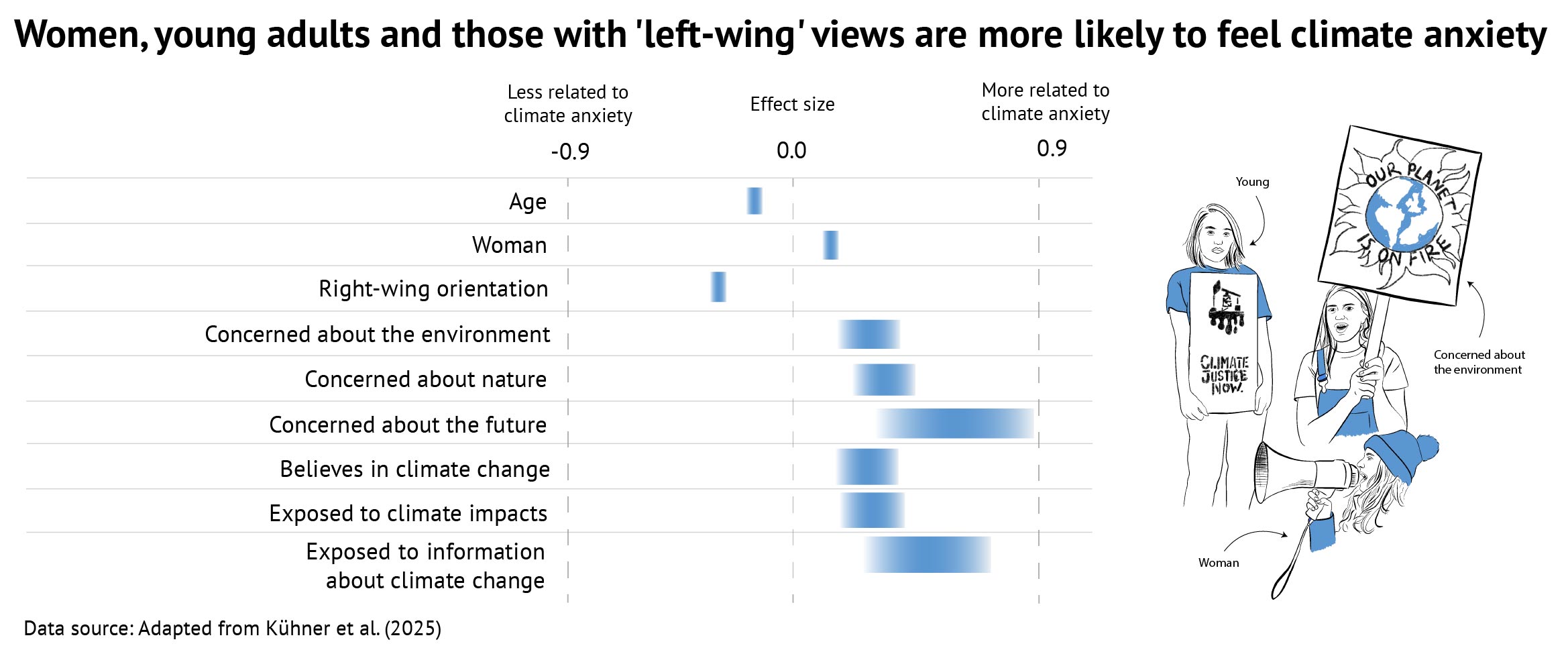

It finds that those who are more likely to experience climate anxiety include women, young adults, people with “left-wing” views and those expressing “concerns” about nature or the “future”.

Climate anxiety is negatively related to wellbeing, according to the analysis, but positively related to participating in climate action, such as activism and behaviours to reduce emissions.

Below, Carbon Brief explains the findings in more detail.

- What is ‘climate anxiety’?

- Who suffers from climate anxiety?

- What are the consequences of climate anxiety?

- How does climate anxiety differ from general anxiety?

What is ‘climate anxiety’?

“Climate anxiety” can be described and defined in various ways.

The research, published in the journal Global Environmental Change, considers the term “climate change anxiety” to “broadly refer to people’s feelings of anxiety and/or worry related to climate change”.

This is based on two established definitions, explains study lead author Dr Clara Kühner, a researcher of climate change and psychology at the University of Leipzig, Germany. She tells Carbon Brief:

“There is a discussion in the scientific community about what exactly constitutes climate change anxiety.”

The first definition comes from a 2023 research paper, which describes climate anxiety as “persistent anxiety (apprehensiveness) and worry about climate change”.

The second comes from the American Psychological Association, which in 2020 used the term “eco anxiety” to describe “any anxiety or worry about climate change and its effects”.

Kühner explains that “eco anxiety could be interpreted as being more broadly related to the ecological crisis…but [the American Psychological Association] describe it as any anxiety or worry related to climate change”.

Her team noticed that there has been an “increasing amount of research” into climate anxiety over the past few years, she adds:

“Research on the topic has exploded. That’s a signal that it’s very relevant to researchers, but also to society and the public.

“But it was very difficult to get an overview of this research because it was scattered across different disciplines, not only psychology, but also public health and sociology. And so it was difficult to really know how much is out there. That’s when we thought: ‘OK, let’s put all of that together in a quantitative meta-analysis to get an overall perspective on the topic.’”

For the meta-analysis, Kühner and her team searched online records, scoured scientific conference agendas and contacted other scientists to try to identify all published and upcoming studies looking into climate anxiety.

They focused on studies that had conducted surveys with people self-reporting symptoms of climate anxiety. They also restricted their search to “correlational studies” looking at the links between self-reported climate anxiety and various factors, such as gender, age or political beliefs.

In addition, they only included studies involving people over the age of 18.

In total, the meta-analysis identifies 94 climate anxiety studies, involving 170,000 people in 27 countries.

Some 81 of these studies were published after 2020, according to the researchers – reflecting the surge of research interest into the topic over the past few years.

Who suffers from climate anxiety?

As part of the meta-analysis, the researchers looked across the 94 studies to identify what characteristics are most highly associated with having climate anxiety.

From this, the meta-analysis finds that those more likely to report feeling climate anxiety include:

- Younger adults

- Women

- People with a “left-wing” political orientation

- People concerned about the environment

- People concerned about nature

- People concerned about the future

- People who believe in climate change

- People who have been exposed to climate impacts

- People who are regularly exposed to information about climate change (such as climate scientists, journalists and teachers)

The graphic below shows the relative “effect size” of each of these characteristics, according to the study, with -0.9 illustrating the trait is less related to climate anxiety and 0.9 indicating it is more related.

On the graphic, the centre of each blue bar represents the effect size, with the start and end showing 95% confidence intervals.

By contrast, people with the opposite characteristics to those listed above – for example, those that are older, male or hold “right-wing” political views – are less likely to report feeling climate anxiety, according to the research.

The study only examines the correlations between feeling climate anxiety and various human characteristics – and does not look into the reasons why different groups of people may be more likely to experience climate anxiety.

One of the research papers cited in the meta-analysis finds that people under the age of 25 who reported climate anxiety were likely to have feelings of “betrayal” aimed towards older generations and to perceive governmental response to climate change as “inadequate”.

On gender, previous research – not cited in the meta-analysis – has found that women are more likely than men to suffer from mental illness following extreme weather events – and face higher health risks from climate change in general.

The meta-analysis does not look into how being transgender or non-binary could be associated with climate anxiety, but researchers have previously argued that these groups – along with other people who might identify as LGBTQ+ – are likely to face disproportionate climate risks.

The meta-analysis also does not investigate where in the world levels of climate anxiety could be the highest.

Most of the papers included in the meta-analysis were conducted in the global north.

Out of the 94 studies, 56 were conducted in Europe, 12 in North America, seven in Australia and New Zealand, seven in Asia, one in Africa and one in South America. (A further 10 spanned multiple continents.)

This “largely reflects the general dominance of western research in mainstream psychological and behavioural studies” – rather than a weakness of the authors’ methods, says Prof Kim-Pong Tam, an environmental psychologist from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, who was not involved in the meta-analysis.

He describes the findings as “very significant”, adding:

“It should be noted that the pattern revealed in this meta-analysis does not necessarily indicate that the phenomenon of interest has rarely been studied in the global south or outside of western societies.

“It is common practice for authors conducting a meta-analysis to focus on publications in the language(s) in which they are proficient. This implies that studies published in non-English languages (usually in local journals), if any, are excluded.”

Dr Charles Ogunbode, an associate professor in psychology specialising in how people respond to environmental change at the University of Nottingham, UK, agrees that the “lack of studies from Africa and other parts of the global south is not a unique weakness of this article”.

He says that the “climate anxiety discourse is western-centric”, explaining:

“Outside of western cultures, climate anxiety may not feel like an especially useful concept for making sense of local lived realities. For example, one study found that feelings of anger and grief regarding climate change are more prominent in Turkey. Another study conducted with young people in three African countries found the predominant emotions to be akin to a helpless pessimism. Similar observations were made in Ecuador.

“It is, of course, valuable to have a comprehensive study on climate anxiety, but the western-centric nature of the concept means that we end up missing out on the nuanced cross-cultural dimensions of emotional responses to climate change.”

What are the consequences of climate anxiety?

As well as examining what human characteristics are most associated with climate anxiety, the meta-analysis explores what consequences are most associated with the phenomenon.

These consequences are grouped into three categories: “wellbeing”, “climate change emotions” and “behaviour”. (The meta-analysis considers “wellbeing” to be “how individuals evaluate the quality of their own lives, including experiences such as life satisfaction”.

The meta-analysis finds that feeling climate anxiety is associated with poor wellbeing and negative feelings about climate change.

However, climate anxiety is also associated with “pro-environmental behaviours”, such as saving energy at home, as well as participating in community activism and showing support for government pro-climate policies. Kühner explains:

“We found that climate change anxiety is a double-edged sword. It [is] related to poorer wellbeing and to more psychological strain. On the other hand, it [is] positively related to different forms of pro-environmental behaviour.

“On the one hand, it could make you feel uncomfortable. But, on the other hand, it may trigger significant action.”

How does climate anxiety differ from general anxiety?

One of the goals of the meta-analysis is to investigate if climate anxiety is a distinct psychological phenomenon – or merely reflects the broader recent trend of rising levels of anxiety across many parts of the world, particularly for younger demographics.

To do this, the researchers carried out a “meta-regression analysis”, a statistical method for, in this case, investigating the size of the impact of various factors on having climate anxiety.

This analysis finds that the characteristics associated with climate anxiety, such as being a young adult or female, as well as its associated consequences, such as taking action to reduce emissions, were “uniquely related to climate anxiety above and beyond generalised anxiety”. Kühner explains:

“From a methodological point of view, this means that these are distinct constructs, not that people who are generally more anxious are also more anxious about climate change.”

This finding could have implications for how both medical professionals and the public view climate anxiety, she continues:

“Sometimes, climate change anxiety is treated like a disease that has to be cured. And it’s not. It’s a normal healthy reaction to an actual threat.

“I think it’s important for policymakers, also journalists and politicians, not to pathologise climate change anxiety, but to interpret it as a functional reaction to something that is actually happening. Instead of offering mental-health support for how to get rid of this, we need more opportunities to channel this anxiety into climate change action.”

In some cases, climate anxiety can cause poor mental health, she adds:

“If [climate anxiety] impairs your daily functioning or affects your sleep, you definitely need mental-health support to cope with these strong emotions.”

In the UK, mental-health support is available from the NHS by calling 111, the charity Mind is also available on 0300 123 3393. In the US, call or text Mental Health America at 988 or chat 988lifeline.org. In Australia, support is available at Beyond Blue on 1300 22 4636, Lifeline on 13 11 14 and at MensLine on 1300 789 978.

The post Explainer: What is ‘climate anxiety’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Greenpeace organisations to appeal USD $345 million court judgment in Energy Transfer’s intimidation lawsuit

SYDNEY, Saturday 28 February 2026 — Greenpeace International and Greenpeace organisations in the US announce they will seek a new trial and, if necessary, appeal the decision with the North Dakota Supreme Court following a North Dakota District Court judgment today awarding Energy Transfer (ET) USD $345 million.

ET’s SLAPP suit remains a blatant attempt to silence free speech, erase Indigenous leadership of the Standing Rock movement, and punish solidarity with peaceful resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Greenpeace International will also continue to seek damages for ET’s bullying lawsuits under EU anti-SLAPP legislation in the Netherlands.

Mads Christensen, Greenpeace International Executive Director said: “Energy Transfer’s attempts to silence us are failing. Greenpeace International will continue to resist intimidation tactics. We will not be silenced. We will only get louder, joining our voices to those of our allies all around the world against the corporate polluters and billionaire oligarchs who prioritise profits over people and the planet.

“With hard-won freedoms under threat and the climate crisis accelerating, the stakes of this legal fight couldn’t be higher. Through appeals in the US and Greenpeace International’s groundbreaking anti-SLAPP case in the Netherlands, we are exploring every option to hold Energy Transfer accountable for multiple abusive lawsuits and show all power-hungry bullies that their attacks will only result in a stronger people-powered movement.”

The Court’s final judgment today rejects some of the jury verdict delivered in March 2025, but still awards hundreds of millions of dollars to ET without a sound basis in law. The Greenpeace defendants will continue to press their arguments that the US Constitution does not allow liability here, that ET did not present evidence to support its claims, that the Court admitted inflammatory and irrelevant evidence at trial and excluded other evidence supporting the defense, and that the jury pool in Mandan could not be impartial.[1][2]

ET’s back-to-back lawsuits against Greenpeace International and the US organisations Greenpeace USA (Greenpeace Inc.) and Greenpeace Fund are clear-cut examples of SLAPPs — lawsuits attempting to bury nonprofits and activists in legal fees, push them towards bankruptcy and ultimately silence dissent.[3] Greenpeace International, which is based in the Netherlands, is pursuing justice in Europe, with a suit against ET under Dutch law and the European Union’s new anti-SLAPP directive, a landmark test of the new legislation which could help set a powerful precedent against corporate bullying.[4]

Kate Smolski, Program Director at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, said: “This is part of a worrying trend globally: fossil fuel corporations are increasingly using litigation to attack and silence ordinary people and groups using the law to challenge their polluting operations — and we’re not immune to these tactics here in Australia.

“Rulings like this have a chilling effect on democracy and public interest litigation — we must unite against these silencing tactics as bad for Australians and bad for our democracy. Our movement is stronger than any corporate bully, and grows even stronger when under attack.”

Energy Transfer’s SLAPPs are part of a wave of abusive lawsuits filed by Big Oil companies like Shell, Total, and ENI against Greenpeace entities in recent years.[3] A couple of these cases have been successfully stopped in their tracks. This includes Greenpeace France successfully defeating TotalEnergies’ SLAPP on 28 March 2024, and Greenpeace UK and Greenpeace International forcing Shell to back down from its SLAPP on 10 December 2024.

-ENDS-

Images available in Greenpeace Media Library

Notes:

[1] The judgment entered by North Dakota District Court Judge Gion follows a jury verdict finding Greenpeace entities liable for more than US$660 million on March 19, 2025. Judge Gion subsequently threw out several items from the jury’s verdict, reducing the total damages to approximately US$345 million.

[2] Public statements from the independent Trial Monitoring Committee

[3] Energy Transfer’s first lawsuit was filed in federal court in 2017 under the RICO Act – the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a US federal statute designed to prosecute mob activity. The case was dismissed in 2019, with the judge stating the evidence fell “far short” of what was needed to establish a RICO enterprise. The federal court did not decide on Energy Transfer’s claims based on state law, so Energy Transfer promptly filed a new case in a North Dakota state court with these and other state law claims.

[4] Greenpeace International sent a Notice of Liability to Energy Transfer on 23 July 2024, informing the pipeline giant of Greenpeace International’s intention to bring an anti-SLAPP lawsuit against the company in a Dutch Court. After Energy Transfer declined to accept liability on multiple occasions (September 2024, December 2024), Greenpeace International initiated the first test of the European Union’s anti-SLAPP Directive on 11 February 2025 by filing a lawsuit in Dutch court against Energy Transfer. The case was officially registered in the docket of the Court of Amsterdam on 2 July, 2025. Greenpeace International seeks to recover all damages and costs it has suffered as a result of Energy Transfers’s back-to-back, abusive lawsuits demanding hundreds of millions of dollars from Greenpeace International and the Greenpeace organisations in the US. The next hearing in the Court of Amsterdam is scheduled for 16 April, 2026.

Media contact:

Kate O’Callaghan on 0406 231 892 or kate.ocallaghan@greenpeace.org

Climate Change

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

The Trump administration’s relentless rollback of public health and environmental protections has allowed widespread toxic exposures to flourish, warn experts who helped implement safeguards now under assault.

In a new report that outlines a dozen high-risk pollutants given new life thanks to weakened, delayed or rescinded regulations, the Environmental Protection Network, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group of hundreds of former Environmental Protection Agency staff, warns that the EPA under President Donald Trump has abandoned the agency’s core mission of protecting people and the environment from preventable toxic exposures.

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

Climate Change

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

The country’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas benefited from what critics say is a questionable IRS interpretation of tax credits.

Cheniere Energy, the largest producer and exporter of U.S. liquefied natural gas, received $370 million from the IRS in the first quarter of 2026, a payout that shipping experts, tax specialists and a U.S. senator say the company never should have received.

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits