Welcome to Carbon Brief’s Cropped.

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Drought around the world

GLOBAL DROUGHT: Drought affected 1.84 billion people in 2022 and 2023 – nearly one-quarter of all people on Earth – “the vast majority” of whom live in low- and middle-income countries, the New York Times wrote. The figures come from the UN’s “Global Drought Snapshot” report. The New York Times explained that the droughts “come at a time of record-high global temperatures and rising food-price inflation”, with conflicts such as Ukraine “punishing the world’s poorest people”. The outlet said: “Some of the current abnormally dry, hot conditions are made worse by the burning of fossil fuels that cause climate change.” It added that the onset of El Niño last year “has also very likely contributed” to the heat and drought.

SHIP-SHAPE: Drought is also impacting the flow of global shipping, as “critical shipping delays” have plagued the Panama Canal, Bloomberg reported. The canal handles around $270bn of global trade each year – about 5% of total commerce. “Potential solutions”, the outlet wrote, “include an artificial lake to pump water into the canal and cloud seeding to boost rainfall”. But, it added, it is unclear if either option is feasible – and neither would be able to be implemented quickly. Moller-Maersk, the Danish shipping giant, has announced that it will “turn to rail to move some cargo”, according to Reuters. The newswire added that the Panama Canal Authority is “developing short- and long-term solutions to limit climate anomalies’ impact on the trade route”.

LOOKING FORWARD: The Global Drought Monitor Consortium released its 2023 summary report, which found that the record heat experienced last year “affected the water cycle in various ways”, including by exacerbating drought conditions. Looking forward, the report said, “the greatest risk of developing or intensifying drought” over the next year is in much of central and South America, southern Africa and western Australia. According to the Global Drought Monitor, global precipitation was “close to average” last year, with no clear trend. But, it added, “the number of record low monthly precipitation totals was the highest on the record”. For more on last year’s record heat, see Carbon Brief’s 2023 state of the climate analysis, published last week.

New year, new species

RIGHT ON KEW: From Antarctic rocks to the top of a volcano, scientists at the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, discovered 74 new species of plants and fungi in 2023, BBC News reported. Of these, “at least one will probably already have been lost”, the story said. Scientists are calling for the immediate protection of new discoveries that include species of Antarctic fungi and a pair of trees living almost entirely underground in highland Angola. Nevertheless, senior research leader at Kew, Dr Martin Cheek, told BBC News: “The sheer sense of wonder when you realise that you’ve found a species that is totally unknown to the rest of the world’s scientists and, in fact, everyone else on the planet, in many cases, is what makes life worth living.”

ANIMAL INVENTORY: Separately, the Zoological Survey of India declared that 664 new animal species were discovered in 2022, according to a story by Mid-day profiling the wildlife researchers behind these finds. “It is both hopeful and intriguing to know that there is something new in a particular patch of forest…but it is tough not to be worried by changes,” said University of Arkansas researcher Shantanu Joshi, who discovered a rare dragonfly species and gave a local family credit as co-authors of his research. Citizens and communities aiding these discoveries are “a contrast to the grim reality” of having to witness “radical and swift destruction of habitats” first-hand, the story added. But they face “systemic challenges”, including the lack of funding and opportunities and the state of documentation and inventorying in India, the story said.

DEEP-SEA DISCOVERY: Meanwhile, New Scientist reported that four new species of deep-sea octopus were discovered at depths of 3km near hydrothermal vents off the coast of Costa Rica. “It’s like walking in a forest you’ve never been in before, with a flashlight, trying to find a hot spring,” said expedition co-leader Dr Beth Orcutt from the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences. Separately, the “largest ever study of ocean DNA” revealed fungi species in the ocean’s “twilight zone” that could yield “new drugs that may match the power of penicillin”, the Guardian reported. And a feature in Hakai Magazine looked at how quickly animals can evolve to adapt to a rapidly changing climate. For Prof Luciano Beheregaray, a molecular ecologist at Flinders University, “hybridisation” is key. He told Hakai: “We could manage populations at risk by actively bringing in genetic material that might help them adapt…It would be better than to sit and watch extinction take place before our eyes.”

Spotlight

Deep-sea disquiet

In this spotlight, Carbon Brief unpacks Norway’s recent decision to allow exploratory seabed mining in its national waters and explains what the next year holds for deep-sea mining approvals.

In December, Norway made headlines around the world as its centre-left minority government struck a deal with two conservative parties to allow companies to explore the seabed of the Arctic Ocean for critical minerals, as covered in Cropped at the time. Last week, the Storting – the Norwegian parliament – officially passed the measure, “against massive criticism from scientists, fisheries organisations and the international community”, EU Reporter wrote.

Seabed mining can involve “hoovering” up rocks called “polymetallic nodules” from the seafloor. These rocks contain metals including manganese, cobalt and nickel, many of which are critical for batteries and other technologies. However, it can also look more like land-based mining – which is “more invasive”, according to Wired.

There are a “huge number of unknowns” associated with seabed mining, Prof David Schoeman, a quantitative ecologist at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Australia, told Carbon Brief last year.

In part, that is because deep-sea habitats are “poorly understood, diverse, fragile and extremely slow to recover from disturbance”, Pepe Clarke, global oceans practice lead at WWF-International, told Carbon Brief. In addition, research previously covered by Carbon Brief has found that seabed mining could negatively impact other important industries, such as fisheries.

At present, the governmental approval covers only exploration for critical minerals, not exploitation of such resources. But, Clarke said: “You don’t explore unless you’re looking for something.”

“Many states view Norway as a sustainable manager of its ocean areas, so what Norway practises and allows in terms of ocean industry is important,” Ida Soltvedt Hvinden of the Fridtjof Nansen Institute told Wired. But it does not directly affect the ongoing negotiations at the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which governs the use of the seafloor in areas beyond any national waters. Twenty-four countries, including the UK, are currently calling for a moratorium on seabed exploration until the risks of environmental harm can be better understood.

There are, essentially, two ways that such a moratorium could come into effect. It could be adopted at the ISA through a formal process. Or, a de facto moratorium could take hold if “a sufficiently large bloc of countries at the ISA committed to withholding support for future mining approvals”, Clarke explained.

Discussions around a seabed exploration moratorium will continue at the ISA this year, with the council scheduled to meet twice and the assembly convening at the end of July. However, Clarke said, it is “unlikely” that the issue will be resolved in the coming year. According to BBC News, a final vote at the ISA is “expected within 24 months”.

News and views

MIXED SIGNALS: Reuters reported that deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest halved in 2023 compared to 2022, hitting its lowest levels since 2018. The newswire called it “a major win for President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva in his first year in office”. But, it pointed out, the area cleared last year is still “six times the size of New York City” – underscoring challenges in Lula’s pledge to end illegal deforestation by 2030. Meanwhile, the Financial Times reported that deforestation in the Cerrado savannah in eastern Brazil rose by 43% in the same time period, with campaigners calling it a “major stain” on Lula’s environmental credentials. Speaking to the FT, André Guimarães of the Amazon Environmental Research Institute said: “Unlike the Amazon, where prevention can be done via law enforcement, in the Cerrado, incentives have to be created for landowners to give up their right to deforest.”

POLAR PATHOGENS: Alaska state officials confirmed that a polar bear found dead in October was killed by the “highly pathogenic avian influenza that is circulating among animal populations around the world”, the Alaska Beacon reported. The state veterinarian said that the death was the first-ever such report in a polar bear anywhere in the world. The outlet added that the death “is a sign of the unusually persistent and lethal hold that this strain” has on wild animal populations. At the other end of the world, the first bird flu deaths in elephant and fur seals were confirmed on South Georgia Island, a UK territory in the sub-Antarctic. “Hundreds of elephant seals were found dead” on the island, the Guardian reported, adding that there “have also been increased deaths of fur seals, kelp gulls and brown skua at several other sites”.

OVERSATURATED: Important crop-growing areas of England were hit by “widespread flooding”, leading to “concerns about shortages of carrots and other root vegetables”, according to the Times. “Prolonged rain” during Storm Henk earlier this month resulted in sustained flooding. The newspaper wrote that “saturated ground is a problem for growers because as long as the crop is in the ground, there’s greater risk of it rotting”. Prof Hannah Cloke, a hydrologist at the University of Reading, pointed out that the floods compounded issues brought on by a “very wet autumn”. She told the outlet: “October’s Storm Babet is already likely to have caused big impacts on potato and cereal crops and damaged this year’s harvest.”

SEED CHANGE: After two consecutive years of heatwaves and other extreme weather taking a toll on yields from India’s wheat bowl, government surveys showed that 80% of the “wheat area this year has been sown with climate-resilient and bio-fortified varieties,” the Hindustan Times reported. The 2022 heatwave reduced India’s wheat yield by 4.5% “compared to a year with normal weather”, according to a study by the University of British Columbia quoted in the story. Separately, Mongabay reported on the combined impact of air pollution and climate change on India’s food security. And Context News reported that while past election manifestos have made only “passing references” to climate impacts on farmers, “crop-threatening erratic monsoon rains and heatwaves could make headlines as campaigning starts” in India’s big general election in April.

SNOWLESS SLOPES: Gulmarg, a skiing town in the Indian-controlled part of Kashmir, witnessed a lack of snow on its ski slopes “due to unseasonably dry weather”, CNN reported, despite being one of the world’s highest ski resorts. The region saw an “80% rain deficit” in December, the Associated Press reported, with daytime temperatures “sometimes at least 6C higher than the norm”. The head of the India Meteorological Department’s Kashmir office, Mukhtar Ahmed, told the newswire that in the last few years, “winter has shortened due to global warming”. This has affected hydropower generation, tourism and agriculture, the article reported, forcing “distressed” farmers to change the crops they plant. Ahmed added that “timely snowfall is crucial to recharge the region’s thousands of glaciers” that sustain agriculture and horticulture. Scientists told the Third Pole that snowless winters and more extreme summer rain could become the norm.

GAZA FAMINE: “Pockets of famine” already exist in Gaza according to UN aid officials, the Guardian reported, with parents sacrificing food for their kids, cooking fuel “almost impossible to find” and 25 kilo sacks of flour now six times their pre-war price. However, lack of data on child malnutrition and mortality meant formal criteria for declaring a famine had not been met, the story said. In a joint statement, the World Health Organisation, World Food Programme and UNICEF said new aid routes must be opened to Gaza, more trucks must be allowed in and aid workers must be protected. According to doctors in Gaza, children “weakened by lack of food had died from hypothermia” and babies born to undernourished mothers “had not survived for more than a few days”.

Watch, read, listen

TRACKED CHANGES: In a news feature, Nature examined how scientists are using gene-editing to domesticate wild plants and concerns around the exploitation of Indigenous and traditional knowledge.

GRISLY NEWS: Are US authorities attributing wildlife declines to predators and overlooking climate impacts on biodiversity? A long-read in Grist unpacked how this has played out in Alaska.

NUTS ABOUT CHESTNUTS: In the Atlantic, staff writer Katherine J Wu explored the downfall of the American chestnut tree and scientists’ attempts to restore the species to its native range.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?: An article in Atmos argued that the way humans talk about nature shapes their relationship to it – and asked whether “we [should] be paying more attention to the words we use?”.

New science

Severe 21st-century ocean acidification in Antarctic marine protected areas

Nature Communications

A new study found that even under intermediate warming over the next century, proposed and existing marine protected areas in the Antarctic will experience “severe” ocean acidification. Using a high-resolution model of the ocean, sea ice and biogeochemistry, researchers projected future ocean acidification under four emissions scenarios. They found that pH in the upper 200 metres of the ocean may decline by up to 0.36, and that these declines will be most severe in coastal areas, where organisms are most sensitive to acidification. The researchers “call for strong emission-mitigation efforts and further management strategies to reduce pressures on ecosystems”.

Consistent patterns of common species across tropical tree communities

Nature

Around 1,050 species make up half of the Earth’s 800bn tropical trees, according to new research. The study, with 357 authors, investigated patterns of abundance of common tree species using inventory data for more than one million trees in old-growth tropical forests across Africa, Amazonia, and south-east Asia. The authors found that despite different histories, there were consistent patterns in common tree species across all continents, suggesting that the “fundamental mechanisms of tree community assembly may apply to all tropical forests”. While their findings “should not detract” from the focus on rare and endemic species, the researchers conclude that it “open[s] new opportunities to understand the world’s most diverse forests”.

Living in harmony with nature is achievable only as a non-ideal vision

Environmental Science & Policy

A new study found that “a dynamic relationship with nature is a constitutional right” for citizens of only four out of 193 countries with constitutions in force: Ecuador, Bolivia, the Philippines and São Tomé and Príncipe. The authors reviewed national constitutions and environmental and biodiversity policies to understand whether they aligned with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’s vision of “a world living in harmony with nature by 2050”. They argued that while such harmony “has little scope for translation into rational or achievable policy”, it is consistent with legislation that has been increasingly recognising the rights of nature. They concluded by calling on politicians to “shift Earth-centred governance from an aspirational party-political issue to a foundational principle through constitutional reforms with policy implications”.

In the diary

- 16-19 January: 60th Session of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change | Istanbul, Turkey

- 23 January: UN Convention on Biological Diversity first meeting of the informal advisory group on benefit-sharing from the use of digital sequence information on genetic resources | Online

- 28 January: Finland presidential election

- 2 February: World wetlands day

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz. Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 17 January 2024: Norway’s deep-sea disquiet; Panama drought; New species discovered appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 17 January 2024: Norway’s deep-sea disquiet; Panama drought; New species discovered

Climate Change

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of America’s Broken Health Care System

American farmers are drowning in health insurance costs, while their German counterparts never worry about medical bills. The difference may help determine which country’s small farms are better prepared for a changing climate.

Samantha Kemnah looked out the foggy window of her home in New Berlin, New York, at the 150-acre dairy farm she and her husband, Chris, bought last year. This winter, an unprecedented cold front brought snowstorms and ice to the region.

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of the Broken U.S. Health Care System

Climate Change

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Two Utah Congress members have introduced a resolution that could end protections for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Conservation groups worry similar maneuvers on other federal lands will follow.

Lawmakers from Utah have commandeered an obscure law to unravel protections for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, potentially delivering on a Trump administration goal of undoing protections for public conservation lands across the country.

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Climate Change

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

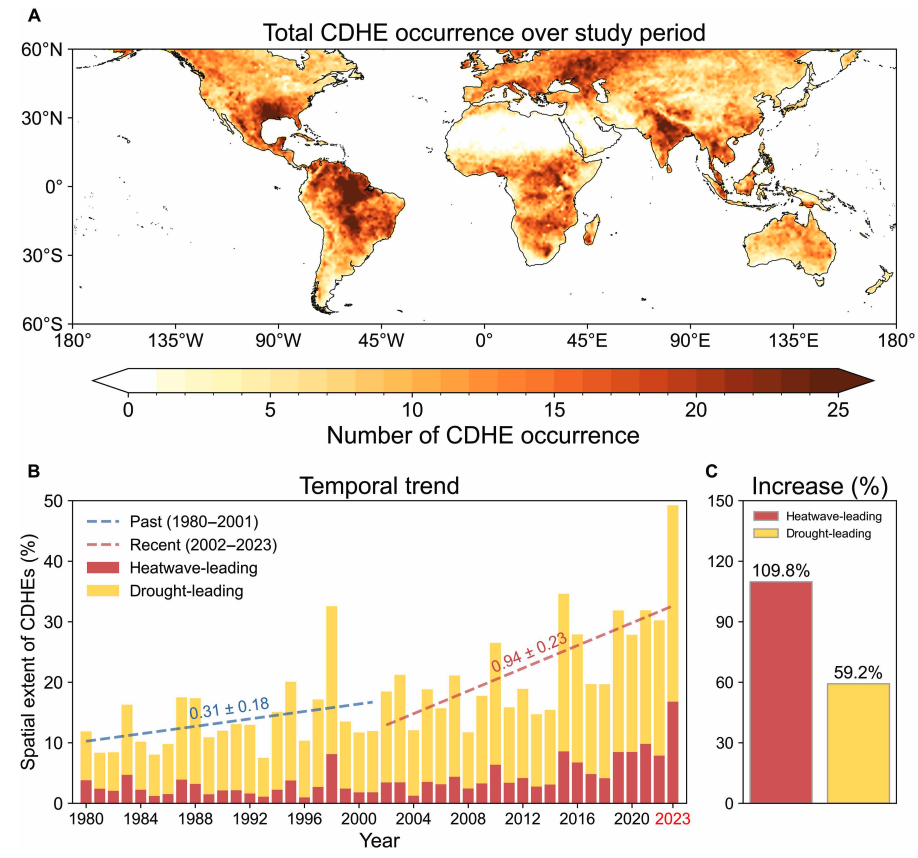

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits