Negotiators are locked in feverish marathon talks to hammer out the final technical draft of the global stocktake. The version published early Tuesday is a 24-page smörgåsbord of wildly ranging alternatives.

Take the energy package. On the defining battle of Cop28 – the fossil fuels conundrum – the draft text lays out two phase out options.

The first simply calls for “an orderly and just phase out of fossil fuels”, reflecting the position of the “high ambition coalition” (France, Kenya, Colombia and others).

The second is wordier. It has qualifiers that give cover to coal, oil and gas: countries should be “accelerating efforts” towards a phase out of “unabated” fossil fuels and “rapidly reducing their use” – but crucially not their production. It’s also more specific about the goal: “net-zero CO2 in energy systems by or around mid-century.”

On the technology side of the package, the text is setting up a repeat of the horse-trading already seen at the G20 this year. A paragraph calling for the tripling of renewable energy capacity by 2030 is followed by one pushing for the scale-up of the “low-emission technologies” preferred by fossil fuel industries, like carbon capture and storage and hydrogen. In Delhi last September the world’s largest economies landed on including both to make everyone happy.

Every paragraph also comes with a “no text” option. This could lead to some “take it or leave it” situations already seen last year in Sharm el-Sheik, observers said. Another iteration of the text is expected today.

Cinderella still waiting for fairy coach

Measures to adapt to climate change have often been called the Cinderella of climate change – ignored and underfed, sitting in rags by the stove while cutting emissions gets all the attention.

And it’s not going to the ball at this Cop either, especially as loss and damage has come strutting in, to hoover up donor governments’ attention and pledges.

The bad news started a few weeks ago when the OECD announced adaptation finance fell 14% between 2020 and 2021.

Then there’s been the Adaptation Fund pledges at Cop28. France and Germany’s are no greater than they were at Cop27 and the US, EU, UK and Japan have yet to chip in.

These don’t seem the actions of governments committed to meeting their Cop26 pledge to double adaptation finance on 2019 levels by 2025.

In global stocktake discussions, some countries want the standing committee on finance to draw up a “roadmap” on how developed countries will meet that target.

A source with knowledge of discussions said developed countries oppose it, as Cop26 only “urges” them to double so its not a commitment.

A group of self-proclaimed “adaptation champion” countries have been looking to multilateral development banks for the funds. They hosted a talk with the World Bank and Asian Development Bank yesterday.

Another source of cash could be carbon markets. But in March, carbon credit sellers like Conservation International and buyers like the BBVA bank fought off an attempt to place a mandatory levy on offsets to fund adaptation.

2021’s adaptation finance figures predate Cop26 and the doubling pledge. We could see better figures for 2022 and meet the goal by 2025.

Even then, it’s a drop in the water. Meeting the goal would be $40 billion a year. The United Nations says adaptation needs will be more like $140-300 billion a year by 2050.

Fossil lobbyist count is in

Figuring out who is and isn’t a fossil fuel lobbyist at Cop28 is painstaking work: over four days a team of researchers, coders and data analysts individually cross-checked 84,000 delegates with public sources for evidence of their fossil fuel interests.

Tears, tantrums, cold pizza slices, vats of coffees and 1.6 million data points were an integral part of the exercise, says Global Witness’ Patrick Galey.

The number he and others in the Kick Big Polluters Out coalition came up with was 2,456.

This is the highest number of coal, oil and gas representatives ever recorded at a UN climate conference. If they were a country, they would form the third largest delegation in Dubai.

In brief

Aussies away… – Australia has promised to stop bankrolling fossil fuel projects overseas with public money. It joins the US, Canada, the UK and many EU states in the Clean Energy Transition Partnership first launched at Cop26. Australia will now have a year to translate words into actions. Most signatories have done so with the notable exception of the US, Germany and Italy.

…and home – It is unclear if and when Canberra will apply similar measures for fossil fuel subsidies at home. Direct spending and tax breaks for producers and users cost Australians an estimated $11.1 billion last year.

Keeping it cool – 60 countries including the US, Canada and Kenya, have signed up to commitments to reduce the climate impact of the cooling sector. Signatories agreed to cut their cooling-related emissions by at least 68% from 2022 to 2050. India and China – two of the world’s largest users of cooling devices – have not joined the coalition.

Doorstepped – Total CEO Patrick Pouyanne was questioned by a campaigner against Total’s East Africa Crude Oil pipeline at Cop28 today. Zaki Mamdoo asked him if he would call on the Ugandan police to release seven student protesters. “That is what we are doing today,” he said.

BOGA grows – Kenya, Spain and Samoa have joined the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance – a coalition of nations led by Denmark and Costa Rica which commit to stop producing oil and gas. None are significant oil and gas producers.

The post Cop28 bulletin: Fossil fuel phase-out language takes shape appeared first on Climate Home News.

Climate Change

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of America’s Broken Health Care System

American farmers are drowning in health insurance costs, while their German counterparts never worry about medical bills. The difference may help determine which country’s small farms are better prepared for a changing climate.

Samantha Kemnah looked out the foggy window of her home in New Berlin, New York, at the 150-acre dairy farm she and her husband, Chris, bought last year. This winter, an unprecedented cold front brought snowstorms and ice to the region.

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of the Broken U.S. Health Care System

Climate Change

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Two Utah Congress members have introduced a resolution that could end protections for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Conservation groups worry similar maneuvers on other federal lands will follow.

Lawmakers from Utah have commandeered an obscure law to unravel protections for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, potentially delivering on a Trump administration goal of undoing protections for public conservation lands across the country.

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Climate Change

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

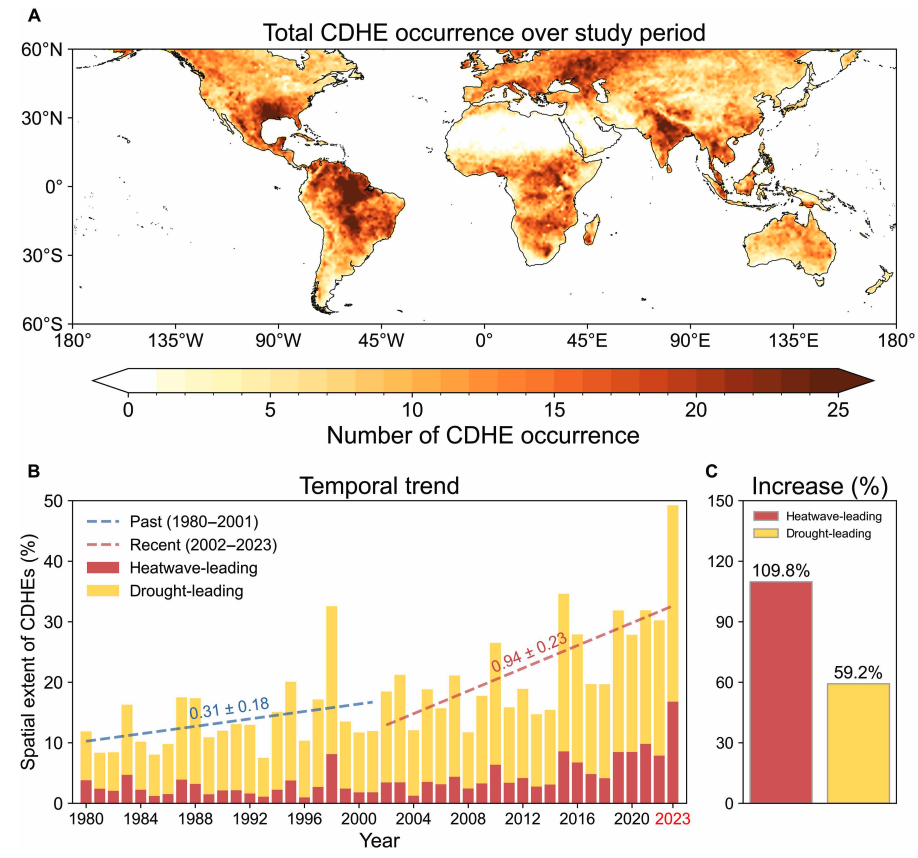

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits