Ben Marshall is a teaching fellow at Harvard University and Aditya Bhayana is a climate fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School.

The dust is settling after COP30, and two things have become clear. First, the outcomes of the world’s most important climate conference were disappointing. Secondly, those outcomes had less to do with the limits of climate science and more to do with geopolitics.

If they want to meaningfully push for better climate agreements, future COP presidencies will need to take a more proactive role in orchestrating climate negotiations and do so in a way that accounts for the new geopolitical reality. If they don’t, climate action will remain mostly talk.

The shortcomings in Belém

Brazil’s COP30 presidency placed three big bets on the 2025 climate summit: it would be “the COP of implementation;” the rainforest setting would unify actors; and wider participation would unlock new avenues for progress.

Instead, the summit – held in Belém (the “gateway to the Amazon”), in the most deforested country on earth – ended with no roadmap for fossil fuel phaseout, an agreement that only briefly mentions deforestation, and an institutional apparatus less trusted than it was at the start.

In part, these outcomes reflect rare missteps by COP President André Aranha Corrêa do Lago, who pushed contentious issues like unilateral trade measures (including the EU’s carbon border tax) into a separate negotiation track and dedicated only a small part of the agenda to political conversation.

But COP30 also suffered from broader issues that are straining multilateralism. Conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East have made it harder to form cross-regional coalitions, record debt distress in developing countries has weakened trust in global institutions, and collaborative efforts to regulate global shipping emissions and reform international taxation have stalled.

How geopolitics show up at COP

Climate diplomacy is becoming less insulated from these geopolitical pressures. Observers noted this during COP28 (Dubai), and since then, it has become more pronounced, while COP hosts have done little in response.

Great-power rivalry is now shaping even technical negotiations, trust in the idea of COP is waning, and the lines between climate and trade are increasingly blurred. At COP30, we saw this firsthand in the form of three key shifts compared to past summits:

Feasibility is no longer the binding constraint. The scientific, technical, and policy cases for rapid decarbonisation have never been stronger – pathways to limit warming to 1.5°C have been well mapped by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; onshore wind and solar power are respectively 60% and ~80% cheaper than in 2015; and each year of inaction measurably raises the costs of mitigation.

But inside the negotiation rooms in Belém, we saw countries not only weighing climate commitments against fiscal, trade, and energy priorities, but also calibrating their positions to avoid antagonising key international partners (chiefly the United States) or empowering domestic political rivals in upcoming elections.

Narrative power has reached its limits. Narratives once turbocharged climate deals, from stories of shared purpose building momentum at COP21 (Paris) to discussions of climate justice pushing “loss and damage” to the fore at COP27 (Sharm-el-Sheikh). But while Brazil saw some of the most compelling storytelling of any COP – with President Lula framing the Amazon as a global commons to be protected, indigenous flotillas on the river, and even the Pope pushing for concrete action – it was not enough to overcome structural blockages to progress on fossil fuels, climate finance or forests.

Emerging powers have gone from adapting to institutions to reshaping them. China, India, Brazil, and the Gulf states are no longer negotiating at the edges of a Western-designed system, but actively redesigning climate governance to reflect their strategic interests. This showed up in a desire to compartmentalise discussions on trade and emissions, and in resistance to overly prescriptive language on mitigation. Red lines will likely continue to harden as developing countries flex – especially if the US stays away from the table.

Action options for future COP presidencies

COP presidencies historically acted as conveners, focusing on the agreement text – largely with the interests of major developed countries in mind. Convening power and elegant drafting are necessary but no longer sufficient. To be successful in the new reality, COP presidencies must act as orchestrators – managing political interdependencies, sequencing issues strategically, and brokering alignment across rival blocs.

Below are four options available to Türkiye and Australia for 2026, and Ethiopia for 2027, to help set up climate negotiations for greater success:

1. Invest in the pre-work to build momentum and trust. The landmark Paris Agreement was achieved in part because ministers were engaged early and often, and expectations were disciplined. COP presidencies should engage political stakeholders throughout the 12 (or ideally, 18) months leading up to the summit and keep a tighter lid on public ambitions. They should also push countries to make good on their commitments if they are to overcome a growing sense of mistrust. This year, more than 70 new national climate plans for 2035 were still missing by the end of COP, including top-10 emitters India, Iran, and Saudi Arabia.

2. Explicitly engage with influential blocs. The COP presidency can play a much more proactive role in brokering agreements. With China, that will mean focusing on implementation (e.g., clean manufacturing, grid-scale deployment and technology diffusion) rather than rehashing mitigation targets.

With other ‘Like-Minded Developing Countries’, including India, it will mean moving from abstract calls for “ambition” toward specific packages that link mitigation to predictable finance, technology access, and transition timelines – especially in hard-to-abate sectors. And with progressives like the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance and AOSIS, it will mean translating “climate leadership” into real economic signals, with the COP presidency pushing existing multilateral institutions to provide access to transition finance in response to ambitious climate commitments.

3. Use creative approaches, but carefully. Brazil offered a response to brittle relationships in the form of mutirão (Portuguese for “collective effort”) sessions. These included closed-door meetings, informal consultations and sidebars, typically without technical staff present, where ministers and high-level delegates could have off-the-record conversations and negotiate political trade-offs that would not survive plenary scrutiny.

Mutirão showed some promise, but its overuse at COP30 degraded transparency and highlighted a paradox in climate diplomacy that the means of identifying compromise and building consensus among some parties also damages trust with others. Future COP presidencies should be careful not to over-use mutirão itself, but instead to design other approaches that structure informal bargaining and connect it to the formal process.

This could include: making political huddles mandatory; baking in more inclusiveness by inviting fixed or rotating representatives from large coalitions (as happens in the G77 and WTO “Green Room” meetings); withholding details on the deliberations themselves but publicly communicating what issues are in scope and any red lines (akin to the forward guidance issued by central banks); and requiring closed-door sessions to feed outcomes back into open negotiating tracks (which helped rapidly translate ministerial consultations into draft text at COP21 in Paris). The combined candour and accountability of these and other approaches could help COP presidencies broker alignment among blocs with fundamentally different political economies.

4. Acknowledge climate governance is entering a post-consensus era. The assumption that all 198 parties to the UNFCCC can converge on a single, high-ambition pathway is no longer credible. Progress will increasingly depend on coalitions of the willing and plurilateral arrangements that complement the multilateral system. COP presidencies should feel comfortable speaking hard truths to power and pushing for stronger, narrower agreements than broader, weaker ones.

The challenge of climate negotiations is no longer knowing what needs to be done or how to do it, but aligning the interests, power and institutions needed to make it possible.

Responding to these dynamics requires a different kind of COP presidency – one focused less on targets and text, and more on managing real-world political priorities. Until geopolitics becomes the starting point of climate action, rather than an inconvenient backdrop, real world implementation will remain a promise deferred.

The opinions expressed in this article the authors’ own and do not necessarily represent those of Harvard or any other institution.

The post COP presidencies should focus less on climate policy, more on global politics appeared first on Climate Home News.

COP presidencies should focus less on climate policy, more on global politics

Climate Change

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of America’s Broken Health Care System

American farmers are drowning in health insurance costs, while their German counterparts never worry about medical bills. The difference may help determine which country’s small farms are better prepared for a changing climate.

Samantha Kemnah looked out the foggy window of her home in New Berlin, New York, at the 150-acre dairy farm she and her husband, Chris, bought last year. This winter, an unprecedented cold front brought snowstorms and ice to the region.

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of the Broken U.S. Health Care System

Climate Change

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Two Utah Congress members have introduced a resolution that could end protections for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Conservation groups worry similar maneuvers on other federal lands will follow.

Lawmakers from Utah have commandeered an obscure law to unravel protections for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, potentially delivering on a Trump administration goal of undoing protections for public conservation lands across the country.

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Climate Change

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

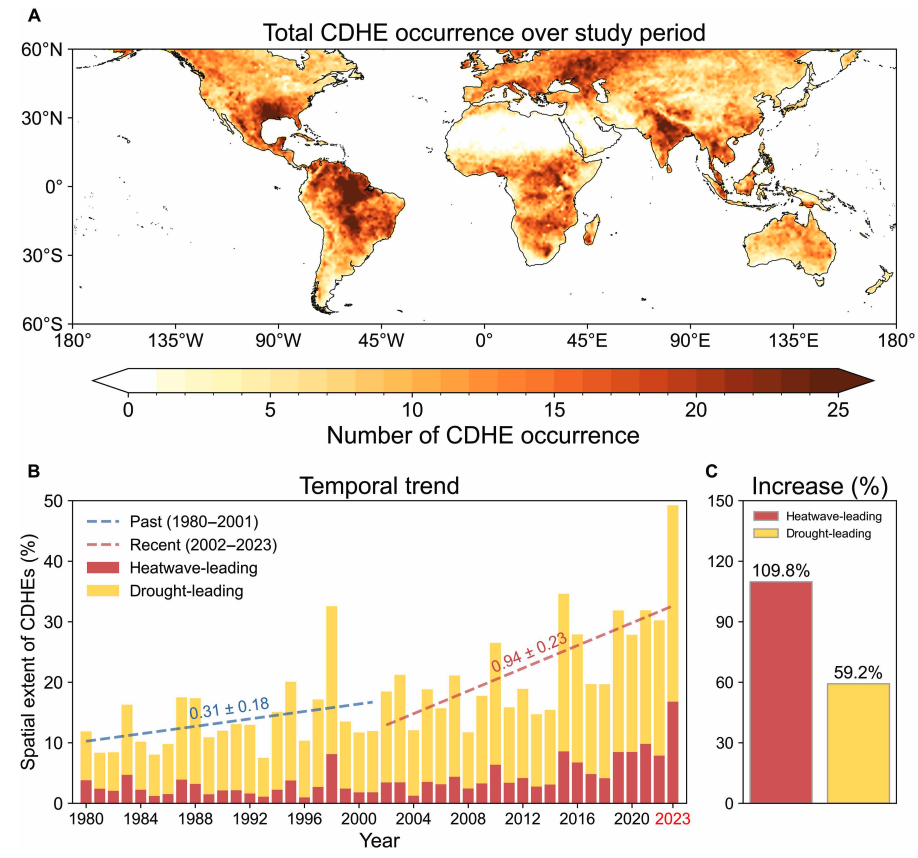

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits