This week marks a major moment in Australia’s long and frustrating struggle to fix its broken national nature laws. The federal government has finally tabled long-awaited reforms to the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act, a piece of legislation that has, ever since it was enacted, failed to protect Australia’s unique wildlife and ecosystems.

But the bill the government has put forward, while offering some positive new legal architecture, unfortunately falls far too short. Critical gaps in addressing deforestation and climate impacts from big coal and gas projects remain, and there is far too much leeway in how the federal environment minister is allowed to apply the law under the proposed new provisions. We’re calling on the Australian Parliament to fix these significant problems and pass laws that properly protect nature.

The Background: A Broken System Finally Gets Attention

It’s been widely acknowledged for over a decade that the EPBC Act is deeply flawed. Despite being Australia’s key environmental law, it has done little to stop habitat loss, species decline, and the relentless clearing of native forests. Native habitat equal to an area the size of Tasmania has been bulldozed in Australia since the EPBC Act came into force in 2000—a stark reminder of the ineffectiveness of the laws.

A major independent review five years ago laid out a roadmap for reform, recommending stronger protections for nature and streamlined approvals for business, including renewable energy projects. The idea was simple: if we establish strong, science-based rules up front and create an independent environmental regulator, we can both protect nature and provide greater certainty for ecologically sustainable development.

Last term the government attempted a partial reform, mainly to establish a national EPA (Environment Protection Authority), but unfortunately this did not eventuate. Now, under new Federal Environment Minister Murray Watt, Labor is trying again and attempting to move at great speed to deliver a full package of legislative reforms before the end of the year.

What’s in the Reform Package?

While there is new legal architecture that could be made strong (new rules and standards and a national Environment Protection Authority), ultimately the current package falls well short of what is actually needed to protect nature. Major improvements are essential to the Bill that is now before the parliament.

At Greenpeace we have four major tests of success:

1. Closing the Deforestation Loopholes

In the current laws, agriculture (particularly beef) and native forest logging remain virtually exempt from the Act, even though deforestation is one of Australia’s major drivers of species extinction and carbon emissions. The current provisions in the Bill do not close these glaring loopholes. Without reform here, Australia’s forests, and the wildlife that depend on them remain hideously vulnerable to the mass destruction of bulldozers and chainsaws that currently has our country recognised as a global deforestation hotspot.

This is a big issue we need to keep pushing on to fix—these reforms are not credible without action to close the loopholes around deforestation

2. Stronger Upfront Protections

- The government is introducing stronger upfront environmental tests (the “unacceptable impacts” test), giving the Minister the power to reject development projects outright before assessment if they are going to do serious damage to nature.

This could be made into a strong element of reformed laws

- They are proposing to introduce ‘national environmental standards’ for those projects and regional plans which do get assessed and developed.

This could give clearer delineation of what needs to be done to protect nature but details are yet to be released and there’s too much wriggle room proposed for how these standards are applied

- There will be higher penalties and the power to halt projects that breach conditions are excellent additions.

This is good and has been a long time coming, but does not work as a standalone if the rest of the laws don’t do what’s needed.

- They are proposing to overhaul the biodiversity offset scheme, introducing a ‘net gain’ test where developers are meant to ensure improved overall nature protection and the ‘mitigation hierarchy’ where they have to prove they have tried to avoid and mitigate nature impacts before buying offsets.

But they are planning an offset fund which risks becoming a way for businesses to circumvent obligations, enabling developers to just buy their way out of responsibility- not a good thing.

- A proposal for a system of ‘accreditation’ which would allow states that meet new rules and standards to undertake assessment and approval of development projects.

This is deeply concerning. The Commonwealth should retain its approval powers-especially over damaging fossil fuel projects

- A proposal to expand on a ‘national interest’ exemption, giving the Environment Minister greater scope to circumvent the new proposed rules.

This is also deeply concerning. This exemption should be tightened to emergencies and security purposes only.

3. A Strong and Independent National Regulator

We will finally see the creation of a National Environment Protection Authority (EPA) — a long-overdue step. However, the Minister will still retain the power to override some decisions.

The proposed level of ministerial discretion risks undermining the regulator’s independence and the overall protective functioning of the Act, and would extend one of the core failures of the current system.

4. Embedding Climate Considerations

Astonishingly, the new national nature law still does not require decision-makers to consider climate impacts. The government has ruled out a ‘climate trigger’ that would require assessment of projects with significant emissions. This omission leaves Australia’s environment exposed to worsening heat, drought, bushfires, and floods driven by fossil fuel expansion. In order to be credible, the EPBC must be meaningfully cognizant of the physical reality of the impact of global warming on the environment and biodiversity that it is intended to protect.

This is another big issue on which we need to keep pushing

As our CEO David Ritter put it:

“The Albanese government was returned to power promising to fix Australia’s broken nature laws and the Bills as they stand do not deliver on that promise. We strongly support overhauling Australia’s broken nature laws. But the Bills as tabled fail to address the two key drivers of extinction and the destruction of nature-deforestation and climate change”

The Road Ahead

The Bills have been tabled in Parliament, and debate is about to heat up. Now the reforms head to a Senate Inquiry — where key negotiations with the Greens, the Coalition and crossbenchers will determine the final shape of the law.

If the Senate moves quickly, the reforms could pass by late November. Alternatively the process could carry into the new year when Parliament next sits.

What Needs to Happen Next

Parliament must now work together to fix the gaps in these Bills. Australia needs a nature law that actually protects nature. One that:

- Closes the loopholes that allow deforestation and logging to continue unchecked

- Embeds climate considerations into the functioning of the Act

- Limits ministerial discretion and strengthens the independence of the EPA

- Ensures there are strong upfront nature protections in place

Meaningful action to address the climate and nature crises will not only safeguard ecosystems, it will secure a safer, more liveable future for all Australians and reinforce our global reputation as a clean, green country.

After years of advocacy, research, and tireless campaigning, we’re closer than ever to real change. But the coming weeks will be crucial. The decisions made now will shape the fate of Australia’s forests, wildlife, and climate for generations to come.

So strap in–the fight for Australia to have effective national nature laws is entering its most important phase yet.

Climate Change

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of America’s Broken Health Care System

American farmers are drowning in health insurance costs, while their German counterparts never worry about medical bills. The difference may help determine which country’s small farms are better prepared for a changing climate.

Samantha Kemnah looked out the foggy window of her home in New Berlin, New York, at the 150-acre dairy farm she and her husband, Chris, bought last year. This winter, an unprecedented cold front brought snowstorms and ice to the region.

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of the Broken U.S. Health Care System

Climate Change

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Two Utah Congress members have introduced a resolution that could end protections for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Conservation groups worry similar maneuvers on other federal lands will follow.

Lawmakers from Utah have commandeered an obscure law to unravel protections for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, potentially delivering on a Trump administration goal of undoing protections for public conservation lands across the country.

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Climate Change

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

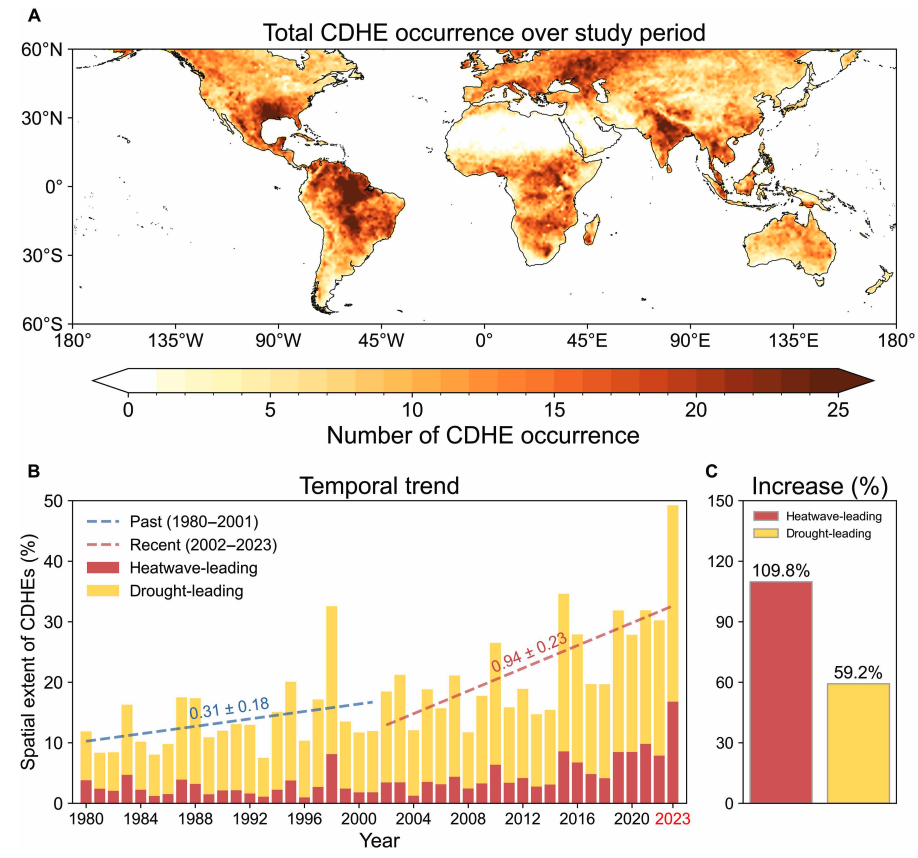

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits