One of the headline outcomes to emerge from COP30 was a new target to “at least triple” finance for climate adaptation in developing countries by 2035.

Vulnerable nations stress that they urgently need to strengthen their infrastructure as climate hazards intensify, but they struggle to attract funding for these efforts.

The new goal, which builds on a previous target agreed four years ago to double adaptation finance by 2025, was a central demand for many developing countries at the UN climate summit in Belém.

Yet, throughout the two-week negotiations, developed-country parties opposed new targets that would give them more financial obligations.

As a result of this opposition, the final target is less ambitious than the idea originally floated by developing countries, resulting in less pressure on developed countries to provide public funds.

This article looks at precisely what the final COP30 outcome does – and does not – say about tripling adaptation finance, as well as the implications for developing countries.

- 1) The final COP30 decision delayed the ‘tripling’ target by five years and added uncertainty

- 2) The new target is looser than the previous ‘doubling’ goal for adaptation finance

- 3) The target also falls far short of developing countries’ adaptation needs

1. The final COP30 decision delayed the ‘tripling’ target by five years and added uncertainty

At COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, a target was agreed for developed nations to double the amount of adaptation finance they would provide to developing countries by 2025.

This target has been broadly interpreted as approximately $40bn by 2025, using the agreed baseline of $18.8bn in 2019.

As of 2022, the latest year for which official data is available, annual adaptation finance from developed countries had reached $28.9bn. (Final confirmation of whether the target has been met will not come until 2027, due to the delay in climate-finance reporting.)

With the “doubling” target set to expire this year, some developing countries came to COP30 with the aim of agreeing on a new target.

The least-developed countries (LDCs) group called for “a tripling of grant-based adaptation finance by 2030 to at least $120bn”. They were backed by small-island states, the African group and some Latin American countries.

This proposal was included in the first draft of the “global mutirão“, the key overarching decision text produced by the COP30 presidency.

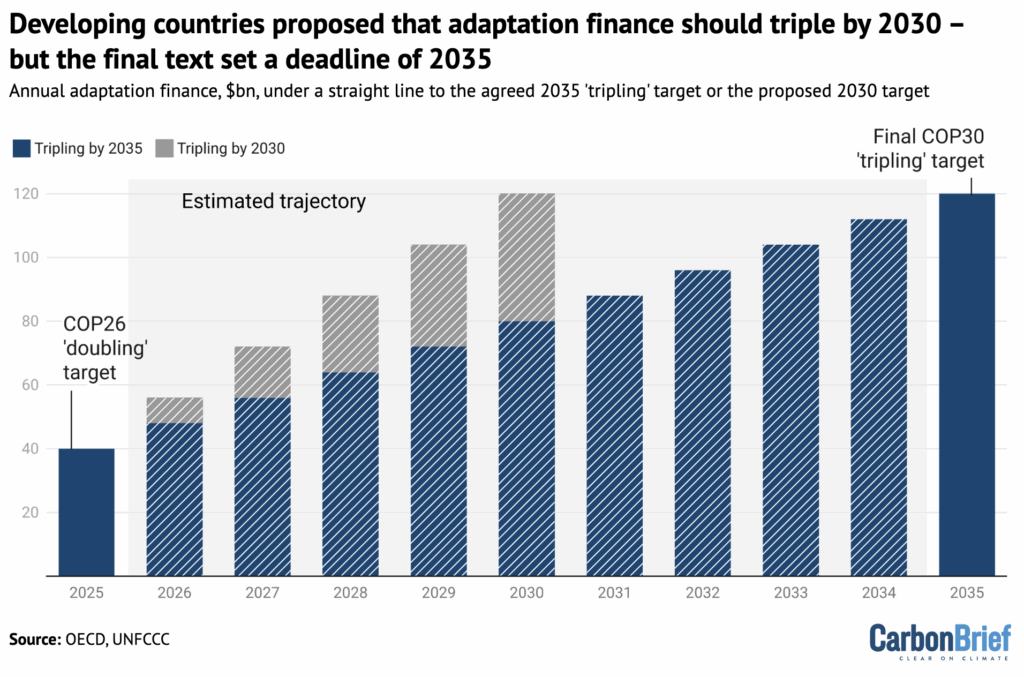

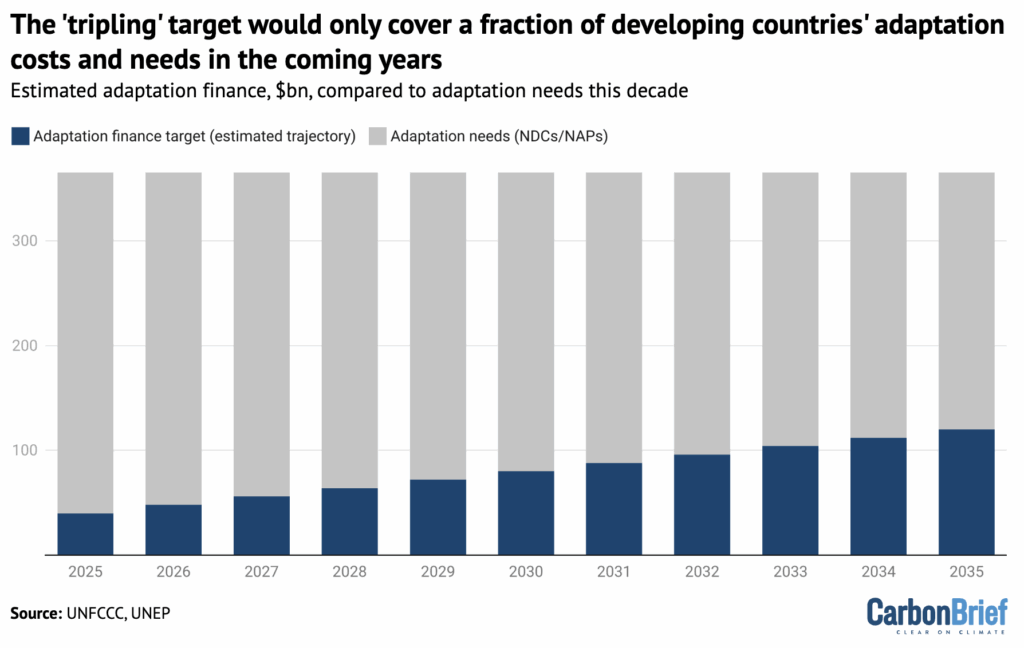

However, the text that ultimately emerged pushed the “tripling” deadline back to 2035. As the chart below shows, this delayed target could mean far less adaptation finance in the short term, due to developed countries taking longer to ramp up their contributions.

Lina Yassin, an adaptation advisor to the LDCs, tells Carbon Brief that this goal is “fundamentally out of step” with the obligation for developed countries to achieve a “balance” between adaptation and mitigation finance.

(This obligation is set out in the Paris Agreement, but, in practice, developed countries provide far more finance for mitigation initiatives, such as clean-energy projects. Adaptation finance has been around a third of the total in recent years and this would still be the case if the overall $300bn climate-finance and tripling adaptation finance targets are both met.)

The final text also removed a mention of 2025 as the baseline year, adding uncertainty as to what precisely the 2035 target means.

“The [LDCs] wanted a clear number, tied to a clear baseline year, that you can actually track and hold providers accountable for,” Yassin explains.

The text does allude to the “doubling” target agreed at COP26 in Glasgow, which some analysts say is an indicator of what the baseline should be.

“It is obviously deliberately vaguely written, but we think the reference to the Glasgow pledge means they should triple that pledge,” Gaia Larsen, director for climate finance access at the World Resources Institute (WRI), tells Carbon Brief.

2. The new target is looser than the previous ‘doubling’ goal for adaptation finance

The “doubling” target set at COP26 was based on adaptation finance “provided” by developed countries.

This means it exclusively comes as publicly funded grants and loans from many EU member states, the US, Japan and a handful of other nations, including finance they raise via multilateral development banks (MDBs) and funds.

The LDCs’ original proposal for the “tripling” goal was even more specific. It called for “grant-based finance”, meaning any loans would not be included.

Amid widespread cuts to aid budgets, notably in the US, developed countries have been unwilling to commit to new targets based solely on them providing public finance.

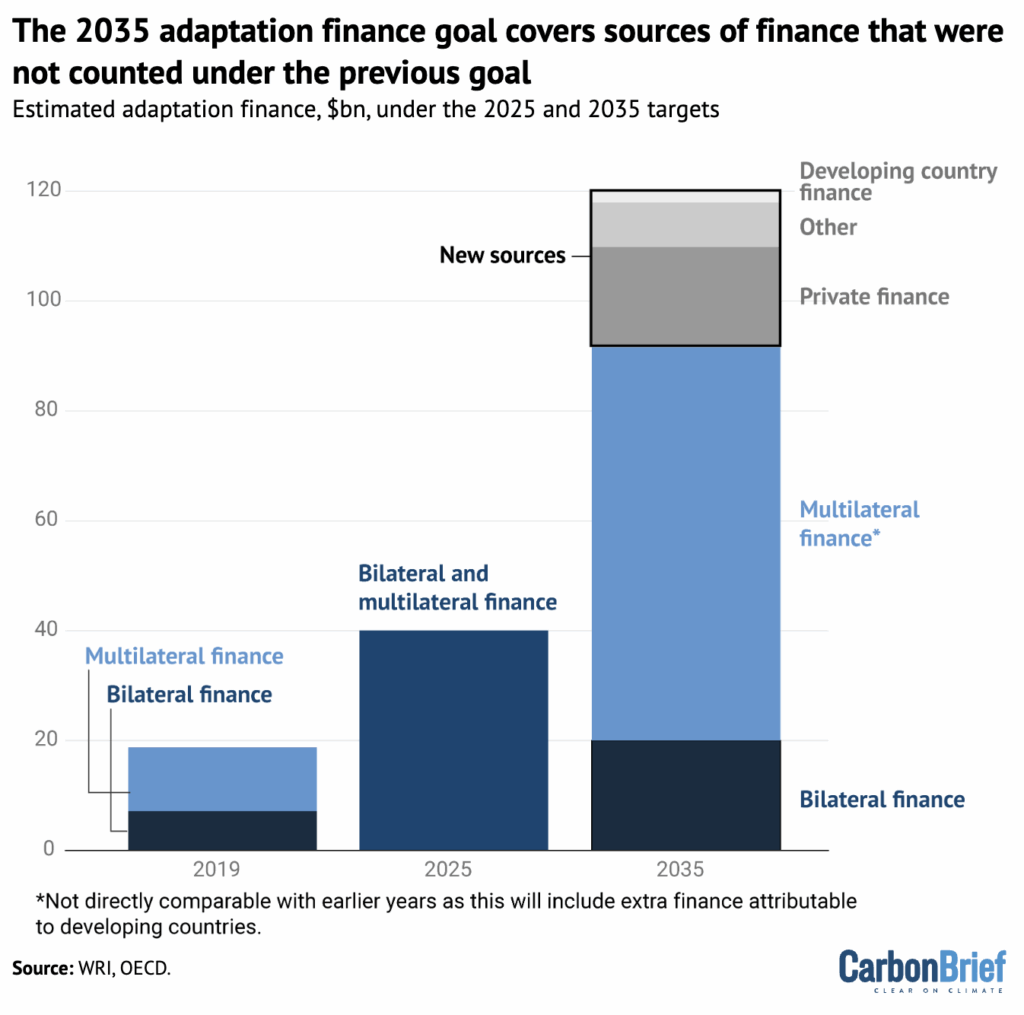

Instead, they stressed at COP30 that any new pledges should align with the “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) to raise $300bn by 2035, which was agreed last year. This is reflected in the final decision, which says the tripling target is “in the context of” the NCQG.

Unlike the COP26 goal, the NCQG covers finance from a variety of sources, including “mobilised” private finance and voluntary contributions from wealthier developing countries.

Assuming $120bn as the 2035 objective, WRI has estimated what its composition could be, based on the looser accounting allowed under the new adaptation-finance goal.

As the chart below shows, the institute estimates that more than a quarter of the target could be met by these new sources, with the rest coming from developed-country governments.

WRI assumes that MDBs will play a “critical role” in meeting the 2035 target, amid calls for them to triple their overall finance. More MDB funding would also automatically be counted, as the new adaptation goal includes MDB funds that are attributable to developing countries, as set out in the NCQG.

The WRI analysis also assumes a big increase in the amount of private finance for adaptation that is “mobilised” by public spending, scaling up significantly to $18bn by 2035.

Traditionally, it has been difficult to raise private investment for adaptation initiatives, as they provide less return on investment than clean-energy projects.

3. The target also falls far short of developing countries’ adaptation needs

The UN Environment Programme’s (UNEP) recent “adaptation gap” report estimates that developing countries’ adaptation investment requirements – based on modelled costs – will likely hit $310bn each year by 2035.

Developing countries have self-reported even higher financial “needs” in their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and national adaptation plans (NAPs) submitted to the UN.

When added together, UNEP concludes these needs amount to $365bn each year for developing countries between 2023 and 2035.

(According to NRDC, most of this discrepancy comes from middle-income countries reporting significantly higher needs than the UNEP-modelled costs.)

As the chart below shows, the new COP30 target would not cover more than a third of these estimated needs by 2035.

Both domestic spending and private-sector investment that is independent of developed-country involvement are expected to play a role in meeting developing countries’ adaptation needs.

Nevertheless, UNEP states that the overarching climate-finance goals set by countries are “clearly insufficient” to close the adaptation-finance “gap”.

Even in a scenario based on the LDCs’ original proposal of tripling adaptation finance to $120bn by 2030, the UNEP report concluded that a “significant” gap would have remained.

The post Analysis: Why COP30’s ‘tripling adaptation finance’ target is less ambitious than it seems appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Why COP30’s ‘tripling adaptation finance’ target is less ambitious than it seems

Climate Change

‘Rush’ for new coal in China hits record high in 2025 as climate deadline looms

Proposals to build coal-fired plants in China reached a record high in 2025, finds a new study.

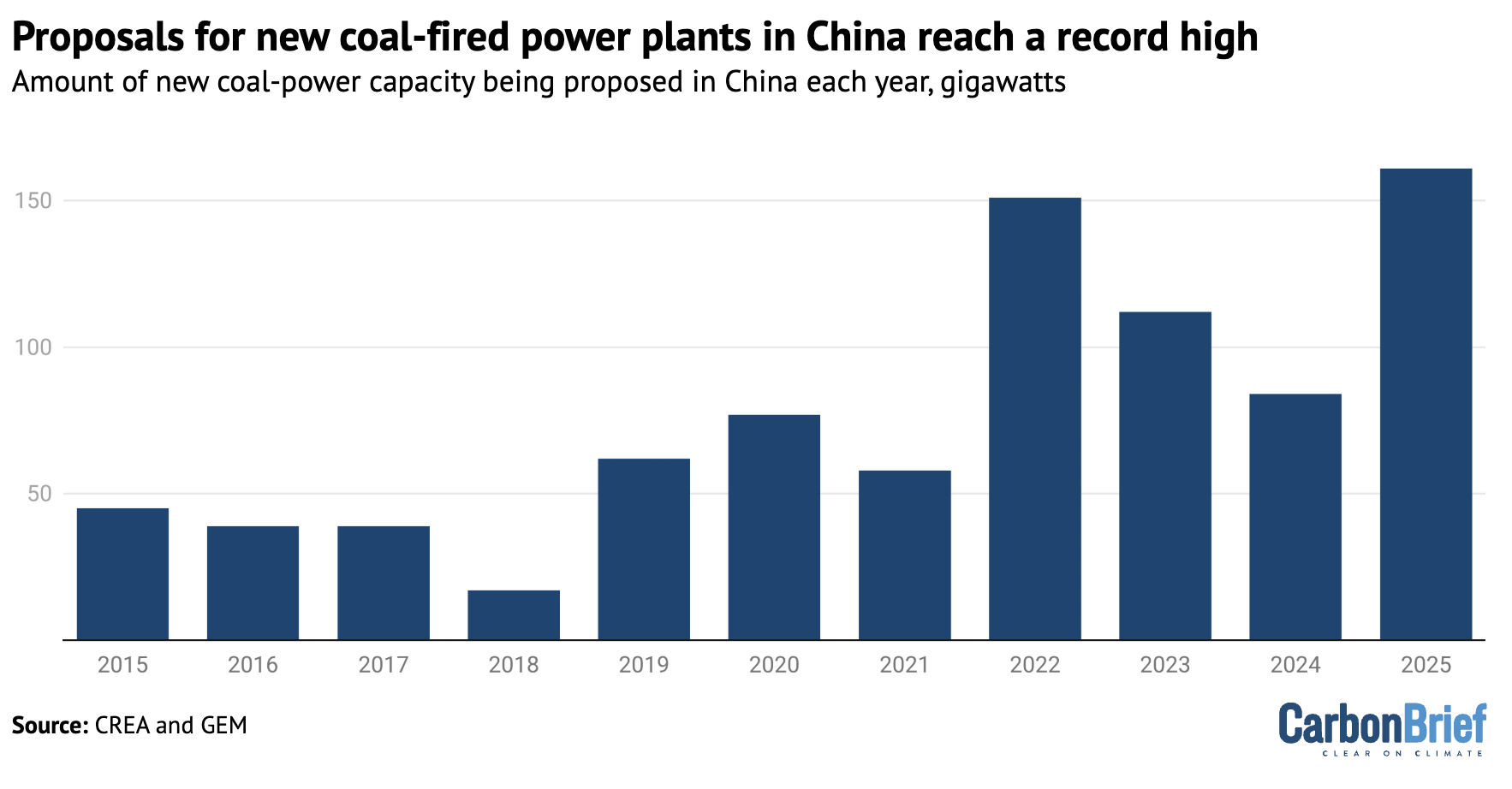

The report, released by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) and Global Energy Monitor (GEM), says that, in 2025, developers submitted new or reactivated proposals to build a total of 161 gigawatts (GW) of new coal-fired power plants.

The new proposals come even as China’s buildout of renewable energy pushed down coal-power generation and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2025, meaning many coal plants are already running at just half of their maximum capacity.

The co-authors argue that while clean-energy growth may limit emissions from coal power in the short term, the surge in proposals could lock in new coal assets, “weaken…incentives” for power-system reform and help keep coal capacity online in spite of China’s climate goals.

The high rate of new proposals, the study says, likely reflects a “rush by the coal industry stakeholders” to develop projects before an expected tightening of climate policy in the next five years.

In addition, “misaligned” payment mechanisms are encouraging developers to propose large-scale coal units, which – if developed – could impact the transition of the coal sector from playing the central role in electricity generation to flexibly supporting a system built on clean power.

Significant additions pushing down running hours

The report finds that the amount of new coal-fired power proposals by Chinese developers, including reactivated applications, hit a new peak in 2025, at 161GW. This is equal to 13% of the coal capacity currently online in China.

The country is continuing to add significant coal-power capacity, with a record 95GW added to the grid last year and another 291GW in the pipeline – meaning units that have been proposed, are actively under construction or have already been permitted.

Moreover, around two-thirds of coal-power capacity proposed in China since 2014 has either been commissioned – meaning it has been completed and started operating – or remains in the pipeline, Christine Shearer, report co-author and research analyst at thinktank Global Energy Monitor, tells Carbon Brief.

She adds that this is the “reverse of what we see outside China, where roughly two-thirds of proposed coal capacity never makes it to construction”.

Coal remains a significant part of China’s power mix, making the nation’s electricity sector one of the world’s largest emitters. Indeed, the power sector emitted more than 5.6bn tonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2) in 2024 – meaning that if it were its own country, it would have the highest emissions of any country except China itself.

But emissions from the power sector have been flat or falling since March 2024, according to analysis for Carbon Brief by CREA lead analyst Lauri Myllyvirta.

This is largely due to China’s rapid installation of renewable power, which is covering nearly all of new electricity demand and pushing coal generation into decline in 2025.

Some parts of the coal-power pipeline are reflecting this shift. In 2025, construction began on 83GW of new coal capacity – down from 98GW in 2024.

In addition, new permitting fell to a four-year low, at 45GW, which could point to tighter controls on coal-plant approvals in the future, says the report.

The chart below shows the amount of new coal-power capacity being proposed in China each year, in GW.

The shift from new power demand being met by coal to being met by renewable energy means any “additional coal power capacity would face structurally low utilisation”, the report says, referring to the number of hours that plants are able to operate each year.

This reduces coal-plant earnings needed to cover the cost of investment and makes instances of “stranded [coal] assets and compensation pressures” more likely.

A previous analysis for Carbon Brief finds that “larger additions of coal capacity are often followed by falling utilisation” – meaning that the construction of new coal plants does not necessarily increase emissions.

Utilisation rates for coal-fired power plants have hovered around 51% since 2025, according to the CREA and GEM report.

Shearer argues that while low utilisation rates would “dampen the immediate impact on annual CO2 emissions”, in the long-term the buildout “locks capital into fossil fuels” and “weakens incentives to build the cleaner forms of flexibility” needed for a renewables-centred system.

Low utilisation has also not led to coal plant capacity being retired in any notable way, the report notes, with generators instead supported by the coal “capacity payment” mechanism and extending the life of older units.

Delayed retirement of older coal plants causes “persistent overcapacity” and adds to calls for further compensation and policy support, the report says.

Coal generation has “no room to expand” under China’s international climate pledge for 2030, it adds, with utilisation rates for coal units likely to fall to 42% if renewables continue to meet all additional demand and if all of the plants currently under construction or permitted are brought online.

Crunch-time for coal

The surge in new proposals reflects a “rush” by the coal industry to ensure their projects are approved before the policy environment tightens, according to the report.

China is expected to introduce absolute emissions targets over the next five years. While these are expected to be aspirational for the first five years – alongside binding targets for carbon intensity, the emissions per unit of GDP – from 2030 they will be binding.

The current five-year period until 2030 will also likely see most of China’s energy-intensive industries pulled into the scope of its national carbon market.

In the power sector, government officials have said that coal is expected to shift from playing a major role in power supply to supporting “flexibility” operations.

This would require coal plants to shift between varying load levels and respond quickly to changes in demand and other system needs.

However, the report finds, the approvals for coal power “continue to reflect expectations of high operating hours”, instead of flexible operations.

For many of these proposals, planned annual utilisation was stated to be more than 4,800 hours, or 55% of hours in the year. This is greater than the 4,685 utilisation hours (53%) logged in 2023, the year in which the most coal power was generated over the past decade, according to data shared by the report authors with Carbon Brief.

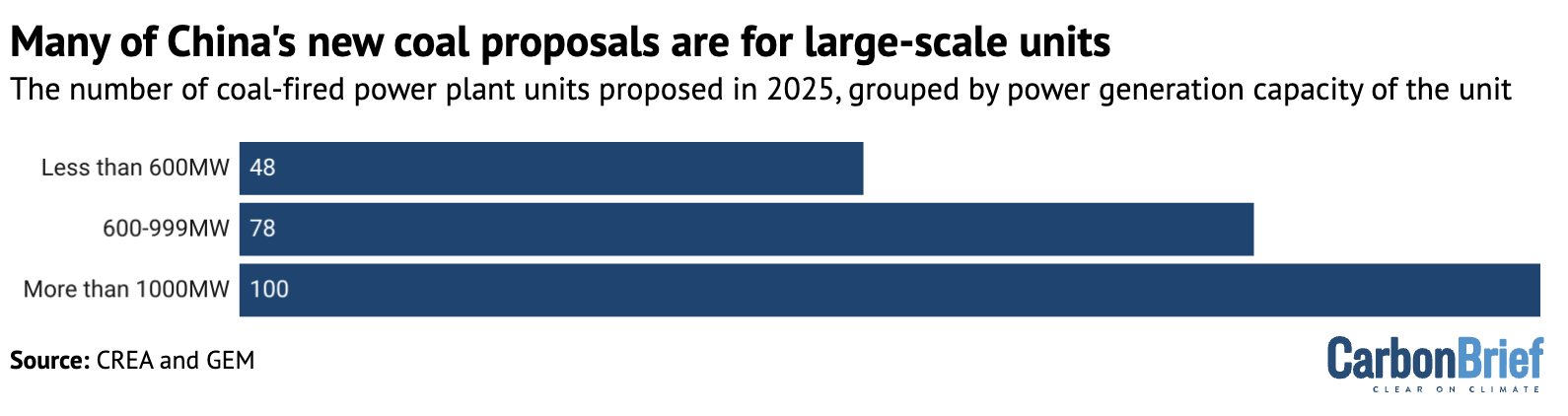

In addition, the report says that many of the new coal-power proposals in 2025 were for “large-scale units”, each representing at least 1GW of power, as shown in the figure below.

These larger units are designed for “stable, continuous operation” and are “poorly suited to the type of flexibility increasingly required in a power system dominated by wind and solar”, says the report.

This suggests that “project developers still anticipated base-load style operation”, it adds, “sitting uneasily” with the fact of higher clean-energy generation and falling coal plant utilisation.

Reliance on sales and subsidies

This persistence in developing large-scale units could be explained by the financial incentives that govern the coal-power industry.

Coal power plants are cheap to build but risk low profits and high costs, with many current operators already facing losses at recent utilisation rates.

In 2024, the government established a capacity payment mechanism for coal-fired power plants. This mechanism rewards developers for adding “seldom-utilised, backup” capacity to the grid.

These capacity payments, as well as regulated pricing and implicit government backing “can make plants viable on paper even if utilisation and operating margins are weak”, Shearer tells Carbon Brief, which may explain the continued appetite for new coal from developers.

More than 100bn yuan ($14bn) in capacity payments were made to coal plants in 2024, although it has not yet had a discernable impact on utilisation.

Large-scale units, the report says, are “particularly well positioned” to benefit from the policy, as it rewards maximising capacity and does not favour plants that are more suited for flexible operations.

(The Chinese government recently announced plans to adjust the mechanism, confirming that in some cases capacity payments could be more than the initial expected threshold of 50% of a benchmark coal plant’s total fixed costs.)

Meanwhile, the report adds that coal-fired power plants continue to earn most of their revenue from selling electricity, with only 5% of total income coming from capacity payments.

As such, these “misaligned incentives” encourage producing power and installing significant new capacity, despite the government’s aim to shift coal to a supporting role in the system.

Shearer tells Carbon Brief that a better approach to flexibility would be to “adopt technology-neutral flexibility standards”, rather than focusing on “flexible coal”, which would mean coal would have to “compete directly with storage, demand response, grid upgrades and other clean options”. She adds:

“The risk of coal-specific flexibility policies is that they lock in capacity rather than solve the underlying system need.”

The post ‘Rush’ for new coal in China hits record high in 2025 as climate deadline looms appeared first on Carbon Brief.

‘Rush’ for new coal in China hits record high in 2025 as climate deadline looms

Climate Change

The EU should partner with Global South to protect carbon-storing wetlands

Fred Pearce is a freelance author and journalist writing on behalf of Wetlands International Europe.

Everybody knows that saving the Amazon rainforest is critical to our planet’s future. But the Pantanal? Most people have never heard of Brazil’s other ecological treasure, the world’s largest tropical wetland – let alone understood its importance, as home to the highest concentration of wildlife in the Americas, while keeping a billion tonnes of carbon out of the atmosphere, and protecting millions of people downstream from flooding.

Hundreds of millions of euros are spent every year on protecting and restoring the world’s forests. Wetlands are just as important, yet don’t get anything like the same recognition or investment. That, scientists insist, has to change. And Europe can lead the way.

For forests, the EU already provides financial and technical assistance for a series of Forest Partnerships with non-EU countries, as part of its Global Gateway strategy for investing globally in environmentally and socially sustainable infrastructure. Such partnerships operate in Guyana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mongolia and elsewhere.

I believe the time is now right to establish a parallel EU Wetland Partnerships, framing wetlands as a strategic, cost-effective investment offering high financial, environmental and social returns.

Wetlands store a third of global soil carbon

Wetlands come in many shapes and sizes: freshwater peatlands, lakes and river floodplains, as well as coastal salt marshes, mangroves and seagrass beds. They are vital natural infrastructure, maintaining river flows that buffer against extreme weather events such as floods and drought, as well as protecting biodiversity, and providing jobs and economic opportunities, often for the most vulnerable nature-dependent communities.

Wetlands cover just six percent of the land surface, but store a third of global soil carbon – twice the amount in all the world’s forests. Yet they have been disappearing three times faster than forests, with 35 percent lost in the past half century.

Their loss adds to climate change, causes species extinction, triggers mass exoduses of fishers and other people whose livelihoods disappear, and depletes both surface and underground water reserves. Continued wetlands destruction is estimated to contribute five percent of global CO2 emissions – more than aviation and shipping combined.

EU Wetland Partnerships can be critical to unlocking finance to stem the losses and realise the benefits by promoting nature-based economic development, such as sustainable aquaculture, eco-tourism, and forms of wetlands agriculture known as paludiculture, while contributing to climate adaptation by improving the resilience of water resources.

Pantanal faces multiple threats

The Pantanal would be a prime candidate for a flagship project. The vast seasonal floodplain stretching from Brazil into Paraguay and Bolivia, is home to abundant populations of cayman, capybaras, jaguars and more than 600 species of birds. It is vital also for preventing flooding on the River Paraguay for some 2000 kilometres downstream to the Atlantic Ocean.

The Pantanal faces multiple threats, from droughts due to upstream water diversions and climate change, invasions by farmers setting fires and a megaproject to dredge the river and create a shipping corridor through the wetland.

But EU investment to achieve partnership targets agreed with Brazil on restoration, conservation and sustainable management could reinvigorate traditional sustainable land use – including cattle ranching that helps sustain the Pantanal’s open flooded grasslands.

Accounting for wetlands carbon in national emissions targets

Africa, a main focus of the Global Gateway, has abundant potential for early partnership initiatives. They include the Inner Niger Delta in Mali, which sustains some three million inhabitants, but is threatened by upstream dams and conflicts over resources between farmers and herders.

Another is the Sango Bay-Minziro wetland, a region of swamp forests, flooded grasslands and papyrus swamp straddling the border between Uganda and Tanzania on the shores of Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest lake.

The two countries have agreed to cooperate in pushing back against illegal logging, papyrus extraction and farming, and Wetlands International has been working with local governments to encourage community-based initiatives. But an EU partnership could dramatically expand this work, helping sustain the wider ecology of Lake Victoria and the Nile Basin.

Deep in the Amazon, forest protection cash must vie with glitter of illegal gold

National pledges to bring wetlands to the fore of environmental action are proliferating rapidly, especially since the 2023 global climate stocktake at COP28 in the UAE emphasised the importance of accounting for wetlands carbon in national emissions targets.

Since then, more than 50 countries have signed up to the 2023 Freshwater Challenge to protect freshwater ecosystems; more than 40 governments with 40 percent of the world’s mangroves have endorsed the 2022 Mangrove Breakthrough that aims to protect and restore 15 million hectares by 2030; and the newly established Peatland Breakthrough aims at rewetting at least 30 million hectares and halting the loss of undrained peatland by 2030.

Such ambition will almost certainly be endorsed at the 2026 UN Water Conference to be hosted by the UAE and Senegal in December this year. But the key to turning targets into reality on the ground lies in finding the billions of Euros needed to deliver on the ambition. EU Wetlands Partnerships could help seal the deal.

The post The EU should partner with Global South to protect carbon-storing wetlands appeared first on Climate Home News.

The EU should partner with Global South to protect carbon-storing wetlands

Climate Change

DeBriefed 30 January 2026: Fire and ice; US formally exits Paris; Climate image faux pas

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Fire and ice

OZ HEAT: The ongoing heatwave in Australia reached record-high temperatures of almost 50C earlier this week, while authorities “urged caution as three forest fires burned out of control”, reported the Associated Press. Bloomberg said the Australian Open tennis tournament “rescheduled matches and activated extreme-heat protocols”. The Guardian reported that “the climate crisis has increased the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, including heatwaves and bushfires”.

WINTER STORM: Meanwhile, a severe winter storm swept across the south and east of the US and parts of Canada, causing “mass power outages and the cancellation of thousands of flights”, reported the Financial Times. More than 870,000 people across the country were without power and at least seven people died, according to BBC News.

COLD QUESTIONED: As the storm approached, climate-sceptic US president Donald Trump took to social media to ask facetiously: “Whatever happened to global warming???”, according to the Associated Press. There is currently significant debate among scientists about whether human-caused climate change is driving record cold extremes, as Carbon Brief has previously explained.

Around the world

- US EXIT: The US has formally left the Paris Agreement for the second time, one year after Trump announced the intention to exit, according to the Guardian. The New York Times reported that the US is “the only country in the world to abandon the international commitment to slow global warming”.

- WEAK PROPOSAL: Trump officials have delayed the repeal of the “endangerment finding” – a legal opinion that underpins federal climate rules in the US – due to “concerns the proposal is too weak to withstand a court challenge”, according to the Washington Post.

- DISCRIMINATION: A court in the Hague has ruled that the Dutch government “discriminated against people in one of its most vulnerable territories” by not helping them to adapt to climate change, reported the Guardian. The court ordered the Dutch government to set binding targets within 18 months to cut greenhouse gas emissions in line with the Paris Agreement, according to the Associated Press.

- WIND PACT: 10 European countries have agreed a “landmark pact” to “accelerate the rollout of offshore windfarms in the 2030s and build a power grid in the North Sea”, according to the Guardian.

- TRADE DEAL: India and the EU have agreed on the “mother of all trade deals”, which will save up to €4bn in import duty, reported the Hindustan Times. Reuters quoted EU officials saying that the landmark trade deal “will not trigger any changes” to the bloc’s carbon border adjustment mechanism.

- ‘TWO-TIER SYSTEM’: COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago believes that global cooperation should move to a “two-speed system, where new coalitions lead fast, practical action alongside the slower, consensus-based decision-making of the UN process”, according to a letter published on Tuesday, reported Climate Home News.

$2.3tn

The amount invested in “green tech” globally in 2025, marking a new record high, according to Bloomberg.

Latest climate research

- Including carbon emissions from permafrost thaw and fires reduces the remaining carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5C by 25% | Communications Earth & Environment

- The global population exposed to extreme heat conditions is projected to nearly double if temperatures reach 2C | Nature Sustainability

- Polar bears in Svalbard – the fastest-warming region on Earth – are in better condition than they were a generation ago, as melting sea ice makes seal pups easier to reach | Scientific Reports

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

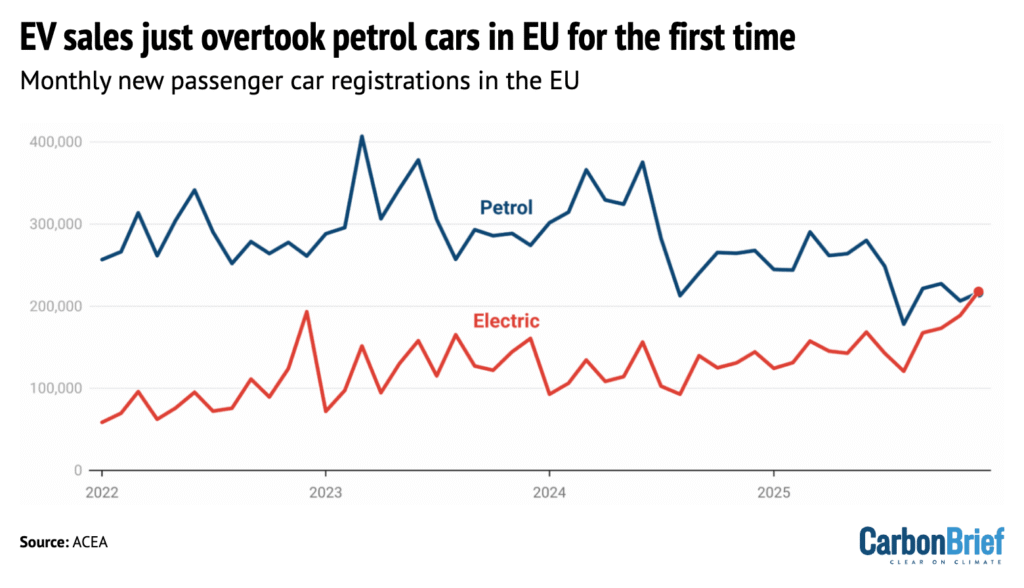

Sales of electric vehicles (EVs) overtook standard petrol cars in the EU for the first time in December 2025, according to new figures released by the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) and covered by Carbon Brief. Registrations of “pure” battery EVs reached 217,898 – up 51% year-on-year from December 2024. Meanwhile, sales of standard petrol cars in the bloc fell 19% year-on-year, from 267,834 in December 2024 to 216,492 in December 2025, according to the analysis.

Spotlight

Looking at climate visuals

Carbon Brief’s Ayesha Tandon recently chaired a panel discussion at the launch of a new book focused on the impact of images used by the media to depict climate change.

When asked to describe an image that represents climate change, many people think of polar bears on melting ice or devastating droughts.

But do these common images – often repeated in the media – risk making climate change feel like a far-away problem from people in the global north? And could they perpetuate harmful stereotypes?

These are some of the questions addressed in a new book by Prof Saffron O’Neill, who researches the visual communication of climate change at the University of Exeter.

“The Visual Life of Climate Change” examines the impact of common images used to depict climate change – and how the use of different visuals might help to effect change.

At a launch event for her book in London, a panel of experts – moderated by Carbon Brief’s Ayesha Tandon – discussed some of the takeaways from the book and the “dos and don’ts” of climate imagery.

Power of an image

“This book is about what kind of work images are doing in the world, who has the power and whose voices are being marginalised,” O’Neill told the gathering of journalists and scientists assembled at the Frontline Club in central London for the launch event.

O’Neill opened by presenting a series of climate imagery case studies from her book. This included several examples of images that could be viewed as “disempowering”.

For example, to visualise climate change in small island nations, such as Tuvalu or Fiji, O’Neill said that photographers often “fly in” to capture images of “small children being vulnerable”. She lamented that this narrative “misses the stories about countries like Tuvalu that are really international leaders in climate policy”.

Similarly, images of power-plant smoke stacks, often used in online climate media articles, almost always omit the people that live alongside them, “breathing their pollution”, she said.

During the panel discussion that followed, panellist Dr James Painter – a research associate at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and senior teaching associate at the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute – highlighted his work on heatwave imagery in the media.

Painter said that “the UK was egregious for its ‘fun in the sun’ imagery” during dangerous heatwaves.

He highlighted a series of images in the Daily Mail in July 2019 depicting people enjoying themselves on beaches or in fountains during an intense heatwave – even as the text of the piece spoke to the negative health impacts of the heatwave.

In contrast, he said his analysis of Indian media revealed “not one single image of ‘fun in the sun’”.

Meanwhile, climate journalist Katherine Dunn asked: “Are we still using and abusing the polar bear?”. O’Neill suggested that polar bear images “are distant in time and space to many people”, but can still be “super engaging” to others – for example, younger audiences.

Panellist Dr Rebecca Swift – senior vice president of creative at Getty images – identified AI-generated images as “the biggest threat that we, in this space, are all having to fight against now”. She expressed concern that we may need to “prove” that images are “actually real”.

However, she argued that AI will not “win” because, “in the end, authentic images, real stories and real people are what we react to”.

When asked if we expect too much from images, O’Neill argued “we can never pin down a social change to one image, but what we can say is that images both shape and reflect the societies that we live in”. She added:

“I don’t think we can ask photos to do the work that we need to do as a society, but they certainly both shape and show us where the future may lie.”

Watch, read, listen

UNSTOPPABLE WILDFIRES: “Funding cuts, conspiracy theories and ‘powder keg’ pine plantations” are making Patagonia’s wildfires “almost impossible to stop”, said the Guardian.

AUDIO SURVEY: Sverige Radio has published “the world’s, probably, longest audio survey” – a six-hour podcast featuring more than 200 people sharing their questions around climate change.

UNDERSTAND CBAM: European thinktank Bruegel released a podcast “all about” the EU’s carbon adjustment border mechanism, which came into force on 1 January.

Coming up

- 1 February: Costa Rican general election

- 3 February: UN Environment Programme Adaptation Fund Climate Innovation Accelerator report launch, Online

- 2-8 February: Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) 12th plenary, Manchester, UK

Pick of the jobs

- Climate Central, climate data scientist | Salary: $85,000-$92,000. Location: Remote (US)

- UN office to the African Union, environmental affairs officer | Salary: Unknown. Location: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- Google Deepmind, research scientist in biosphere models | Salary: Unknown. Location: Zurich, Switzerland

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 30 January 2026: Fire and ice; US formally exits Paris; Climate image faux pas appeared first on Carbon Brief.

DeBriefed 30 January 2026: Fire and ice; US formally exits Paris; Climate image faux pas

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits