A victory for Donald Trump in November’s presidential election could lead to an additional 4bn tonnes of US emissions by 2030 compared with Joe Biden’s plans, Carbon Brief analysis reveals.

This extra 4bn tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) by 2030 would cause global climate damages worth more than $900bn, based on the latest US government valuations.

For context, 4GtCO2e is equivalent to the combined annual emissions of the EU and Japan, or the combined annual total of the world’s 140 lowest-emitting countries.

Put another way, the extra 4GtCO2e from a second Trump term would negate – twice over – all of the savings from deploying wind, solar and other clean technologies around the world over the past five years.

If Trump secures a second term, the US would also very likely miss its global climate pledge by a wide margin, with emissions only falling to 28% below 2005 levels by 2030. The US’s current target under the Paris Agreement is to achieve a 50-52% reduction by 2030.

Carbon Brief’s analysis is based on an aggregation of modelling by various US research groups. It highlights the significant impact of the Biden administration’s climate policies. This includes the Inflation Reduction Act – which Trump has pledged to reverse – along with several other policies.

The findings are subject to uncertainty around economic growth, fuel and technology prices, the market response to incentives and the extent to which Trump is able to roll back Biden’s policies.

The analysis might overstate the impact Trump could have on US emissions, if some of Biden’s policies prove hard to unpick – or if subnational climate action accelerates.

Equally, it might understate Trump’s impact. For example, his pledge to “drill, baby, drill” is not included within the analysis and would likely raise US and global emissions further through the increased extraction and burning of oil, gas and coal.

Also not included are the potential for Biden to add new climate policies if he wins a second term, nor the risk that some of his policies will be weakened, delayed or hit by legal challenges.

Regardless of the precise impact, a second Trump term that successfully dismantles Biden’s climate legacy would likely end any global hopes of keeping global warming below 1.5C.

- The ‘Trump effect’ on US emissions

- How the Biden administration is tackling warming

- What a second-term Trump might do

- The global climate implications of the US election

- How the analysis was carried out

The ‘Trump effect’ on US emissions

US greenhouse gas emissions have been falling steadily since 2005, due to a combination of economic shifts, greater efficiency, the growth of renewables and a shift from coal to gas power.

Since taking office in early 2021, Biden has pledged under the Paris Agreement to accelerate that trend by cutting US emissions to 50-52% below 2005 levels in 2030 and to net-zero in 2050.

He has implemented a long list of policies – most notably the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act – to keep those targets within reach. (See: How the Biden administration is tackling warming.)

In the “Biden” scenario in the figure below (blue line), all federal climate policies currently in place or in the process of being finalised are assumed to continue. The scenario does not include any new climate policies that might be adopted after November’s election.

The administration’s current climate policies are expected to cut US emissions significantly, bringing the country close to meeting its 2030 target range. Nevertheless, a gap remains between projected emissions and those needed to meet the 2030 and 2050 targets (green).

The “Trump” scenario (red line) assumes the IRA and other key Biden administration climate policies are rolled back. It does not include further measures that Trump could take to boost fossil fuels or undermine the progress of clean energy. (See: What a second-term Trump might do.)

For both projections, the shaded area shows the range of results from six different models, with varying assumptions on economic growth, fuel costs and the price of low-carbon technologies.

In total, the analysis suggests that US greenhouse gas emissions would fall to 28% below 2005 levels by 2030 if Trump secures a second term and rolls back Biden’s policies – far short of the 50-52% target. If Biden is reelected, emissions would fall to around 43% below 2005 levels.

In the Trump scenario, annual US greenhouse gas emissions would be around 1GtCO2e higher in 2030 than under Biden, resulting in a cumulative addition of around 4GtCO2e by that year.

Based on the recently updated central estimate of the social cost of carbon from the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) – which stands at some $230 per tonne of CO2 in 2030 – those 4GtCO2e of extra emissions would cause global climate damages worth more $900bn.

To put the additional emissions in context, EU greenhouse gas emissions currently stand at around 3GtCO2e per year, while Japan’s are another 1GtCO2e. If the EU meets its climate goals, then its emissions would fall to 2GtCO2e in 2030 and to below 1GtCO2e in 2040.

Only eight of the world’s nearly 200 countries have emissions that exceed 1GtCO2e per year – and 4GtCO2e is more than the combined yearly total from the 140 lowest-emitting nations.

Expressed another way, the extra 4GtCO2e would be equivalent to double all of the emissions savings secured globally, over the past five years, by deploying wind, solar, electric vehicles, nuclear and heat pumps.

Carbon Brief’s analysis highlights several key points.

First, that Biden’s climate goals for the US in 2030 and 2050 will not be met, without further policy measures after the next election.

This could include additional state-level action, which could yield an additional 4 percentage points of emissions savings by 2030. Added to the “Biden” pathway, this would take US emissions to 47% below 2005 levels – closer to, but still not in line with the 2030 pledge.

Second, despite this policy gap, Biden’s current climate policies go a significant way towards meeting the 2030 target and could be added to in the future.

Third, if Trump is able to remove all of Biden’s key climate policies, then the US is all but guaranteed to miss its targets by a wide margin.

Given the scale of US emissions and its influence on the world, this makes the election crucial to hopes of limiting warming to 1.5C. (See: The global climate implications of the US election.)

Finally, there is policy uncertainty around which policies will be finalised, how strong any final rules will be, what legal challenges they may face and how easy they prove to roll back.

There is also uncertainty – illustrated by the ranges in the chart – around the impact of Biden’s policies, the response of households, business and industry to those measures, and the rate of economic growth, as well as over future prices for fossil fuels and low-carbon technologies.

These uncertainties are partly – but not entirely – captured by the six models underlying the analysis, which have different model structures and input assumptions.

How the Biden administration is tackling warming

In 2015, the then-president Barack Obama pledged a 26-28% reduction in US emissions below 2005 levels by 2025 as an intended “nationally determined contribution” (iNDC) to the Paris Agreement.

On taking office in 2017, the climate-sceptic president Trump then pulled the US out of the Paris Agreement, attracting global opprobrium. He then rolled back or replaced Obama-era climate policies, including the Clean Power Plan, while attempting – unsuccessfully – to prop up coal.

Trump’s successor as president, Joe Biden, campaigned in 2020 on a platform of a “clean energy revolution”. On gaining office in 2021, he immediately rejoined the Paris Agreement and then issued a more ambitious pledge to cut US emissions to 50-52% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Biden also pledged to decarbonise the electricity grid by 2035 and joined roughly 150 other countries in committing the US to reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 – the global benchmark, if the world is to keep warming below 1.5C.

In order to keep these targets within reach, the Biden administration has ushered in a series of climate policies. Most notable is the 2022 IRA, unexpectedly passed by Congress after a 51-50 Senate vote, with the tie broken by the vice president Kamala Harris.

This has been called the largest package of domestic climate measures in US history. It offers incentives covering a broad swathe of the economy from low-carbon manufacturing to clean energy, electric vehicles, “climate-smart” agriculture and low-carbon hydrogen.

The IRA accounts for the most significant part of the emissions reductions expected as a result of Biden’s climate policies to date and shown by the blue line in the figure above.

It includes grants, loans and tax credits initially estimated to be worth $369bn. However, most of the tax credits are not capped, meaning the overall cost and impact on emissions is uncertain.

In general, cost estimates have risen since its passing, as investments triggered by the bill’s incentives have rolled in, with some now putting its ultimate cost above $1tn.

However, a recent analysis of progress since the bill passed in 2021 shows that while electric vehicle sales are running at the top end of what was expected in earlier modelling of the IRA’s impact, the deployment of clean electricity – in particular, wind power – is falling slightly behind.

(Another recent study looks at the behavioural challenges that could affect the success or failure of the IRA, including as a result of political polarisation. Separately, gas power expansion plans from several major US utilities also pose a challenge to the IRA.)

Other Biden administration initiatives with important implications for US emissions include the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, loans for nuclear power plants and new standards on appliance efficiency issued by the Department of Energy.

Meanwhile, the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) has finalised rules on methane emissions from oil and gas facilities. It has also proposed – but not yet finalised – rules on vehicle fuel standards, power plant greenhouse gas standards and power plant air pollution.

The administration is now rushing to finalise these rules within the next couple of months, so that they could not be overturned easily after the election using the Congressional Review Act.

The administration is reportedly planning to weaken its proposed vehicle fuel standards. The final version would retain the original aim of having two-thirds of new sales be all-electric by 2032, but would ease the trajectory to reaching that target, according to the New York Times. This would reduce the emissions-cutting impact, relative to what is assumed in the “Biden” scenario.

Separately, the administration is reported to be exempting existing gas-fired units from its proposed power plant emissions rules, focusing for now on existing coal and future gas-fired units. The New York Times quotes EPA administrator Michael Regan saying this will “achieve greater emissions reductions”, but the timescales could also affect the scenario projection.

Meanwhile, Biden has also overseen a rare Senate approval of an international climate treaty, when it ratified the Kigali Amendment on tackling climate-warming hydrofluorocarbons in 2022, with the US EPA issuing related rules the following year.

In addition, Biden’s time in office has seen further state-level action on emissions. This includes California’s clean car standards, as strengthened in 2022 and adopted by six other states.

What a second-term Trump might do

For his part, former president and Republican front-runner Donald Trump has made no secret of his desire to roll back his predecessor’s climate policies, just as he did during his first term.

For example, in 2018, the Trump administration lifted Obama-era rules on toxic air pollution from electricity generating and industrial sites – with Biden now moving to reverse the reversal.

Similarly, in 2020, his administration rolled back an Obama-era EPA rule on methane emissions from the oil and gas industry. The Biden administration’s methane rule could face a similar fate under a second Trump term.

Trump also has form when it comes to energy efficiency regulations, which he rolled back in 2020.

In November 2023, the Financial Times reported that Trump was “planning to gut” the IRA, increase investment in fossil fuels and roll back regulations to encourage electric vehicles. The newspaper added that Trump had called the IRA the “biggest tax hike in history”.

It quoted Carla Sands, an adviser to Trump, as saying:

“On the first day of a second Trump administration, the president has committed to rolling back every single one of Joe Biden’s job-killing, industry-killing regulations.”

Indeed, Republicans in the US House of Representatives have already made multiple attempts to repeal parts of the IRA. While some analysts think a full repeal of the act is unlikely, it is clear that a second-term Trump could – as Politico put it – ”hobble the climate law”.

A February 2024 commentary from investment firm Trium Capital argues that the impact on IRA will depend not only on whether Trump wins victory in November, but also on whether the Republicans retain control of the House and gain a Senate majority.

Even if the Republicans win all three races, the commentary suggests that some parts of IRA might survive beyond the election. It says that consumer incentives for electric vehicles and home heating are “most at risk”, whereas tax credits for clean energy might only be modified.

Equally, MIT Technology Review says that clean energy and EV tax credits both “appear especially vulnerable, climate policy experts say”. The publication adds:

“Moreover, Trump’s wide-ranging pledges to weaken international institutions, inflame global trade wars, and throw open the nation’s resources to fossil-fuel extraction could have compounding effects on any changes to the IRA, potentially undermining economic growth, the broader investment climate, and prospects for emerging green industries.”

Meanwhile, Trump has also criticised Biden’s infrastructure act and previously revoked California’s ability to set tougher car emissions standards, which are also adopted by other states.

In 2022, the California “waiver” was reinstated by Biden, who also opposed a 2023 Republican bill designed to remove California’s right to regulate. Yet the waiver is now embroiled in legal action brought by Republican states, expected to end up in the Supreme Court.

If he emerges victorious in November, Trump would also “plan to destroy the EPA”, according to a Guardian article published earlier this month. It reported:

“Donald Trump and his advisers have made campaign promises to toss crucial environmental regulations and boost the planet-heating fossil fuel sector. Those plans include systematically dismantling the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the federal body with the most power to take on the climate emergency and environmental justice, an array of Trump advisers and allies said.”

The paper cites Project 2025, described as “a presidential agenda put forth by the Heritage Foundation and other conservative organisations”. It also quotes Mandy Gunasekara, Trump’s EPA chief of staff and a contributor to the Project 2025 agenda.

After Trump was elected for the first time, many scientists, politicians and campaigners argued that his presidency would only have a relatively short-term effect on emissions and climate goals.

Many of his first-term efforts to rollback climate rules and boost fossil fuels ended in failure.

While some modelling suggested that his first presidency would delay hitting global emissions targets by a decade, Carbon Brief analysis found that US states and cities might be able to take sufficient steps to meet the country’s then-current climate goal without federal action.

However, another recent Guardian article says that a second-term Trump would be “even more extreme for the environment than his first, according to interviews with multiple Trump allies and advisers”. It adds:

“In contrast to a sometimes chaotic first White House term, they outlined a far more methodical second presidency: driving forward fossil fuel production, sidelining mainstream climate scientists and overturning rules that curb planet-heating emissions.”

Carbon Brief’s “Trump” scenario does not include additional fossil fuel emissions as a result of policies supporting coal, oil and gas production or use, as the success or otherwise of any such efforts are highly uncertain.

In addition, higher US fossil fuel production would not all be consumed domestically and would not increase global demand on a one-for-one basis.

While it would be likely to raise demand and emissions, both domestically and internationally, the precise impact would depend on the response of markets and overseas policymakers.

The global climate implications of the US election

If Biden – or another Democrat – wins the election in November and if his party regains control over the House and Senate, then they could push to implement new climate policies in 2025.

There is a clear need for further policy, if US climate goals are to be met. Moreover, the expiration of a large number of tax cuts at the end of 2025 could present an opportunity to deploy carbon pricing in support of raising revenues – and cutting emissions – according to a recent study.

It suggests that a price on emissions, described as a “carbon fee”, could significantly boost US chances of hitting its 2030 target, even if paired with a partial repeal of the IRA.

(Note that the “Repeal IRA; no new emissions rules” scenario in this study is similar to the “Trump” scenario in Carbon Brief’s analysis. However, the model used in the study finds a relatively weak 2030 emissions impact of the IRA compared with most of the five others, with which it is aggregated by Carbon Brief.)

An additional point of leverage is the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), which will put a carbon price on US exports unless they face an equivalent price domestically, according to Democratic senator Sheldon Whitehouse, speaking at a launch event for the study:

“The 2025 opportunity when the Trump tax cuts collapse [creates] huge room for negotiation. Then you’ve got the CBAM happening in Europe that puts enormous pressure to get a price of carbon, if you want to avoid being tariffed at the EU and UK level.”

Whether a second-term Biden administration would attempt to put a price on carbon or not, it would be likely to push forward new policies in pursuit of US climate targets.

In contrast, a victory for Donald Trump could be expected, at a minimum, to result in full or partial repeal of the IRA and rollbacks of Biden’s climate rules, including power plants, cars and methane.

This is reflected in Carbon Brief’s “Trump” scenario, which would add a cumulative 4GtCO2e to US emissions by 2030, as shown in the figure below.

Moreover, assuming no further policy changes, this cumulative total would continue to climb beyond 2030, reaching 15GtCO2e by 2040 and a huge 27GtCO2e by 2050.

The increases in cumulative emissions under the “Trump” scenario are so large that they would imperil not only the US climate targets, but also global climate goals. (Under the 22nd amendment of the US constitution, Trump would not be allowed to run for a third term.)

In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) sixth assessment report (AR6) said that it would be “impossible” to stay below 1.5C without strengthening current pledges:

“[F]ollowing current NDCs until 2030…[would make] it impossible to limit warming to 1.5C with no or limited overshoot and strongly increas[e] the challenge to likely limit warming to 2C.”

The corollary of this is that if the US – the world’s second-largest emitter – misses its 2030 target by a wide margin, then it would be likely to end any hope of keeping global warming below 1.5C.

How the analysis was carried out

The two scenarios set out in this analysis are based on an aggregation of modelling published by Bistline et al. (2023) and the Rhodium Group (2023).

The first study was explained by the authors in a Carbon Brief guest post. It compares the impact of the IRA using results from 11 separate models, some of which only cover the power sector. Carbon Brief’s analysis uses results from the six models that cover the entire US economy.

The “Trump” scenario is based on the “reference” pathway in this study, corresponding to the average of the six models. The only modification is that the Trump scenario is set to match the Biden scenario below until 2024.

The “Biden” scenario is based on the average IRA pathway from this study, extended using modelling from the Rhodium Group to include the impact of further Biden administration policies.

Carbon Brief’s analysis uses the “mid-emissions” pathway from the Rhodium study’s “federal-only” scenario, which includes the impact of vehicle fuel standards, power plant greenhouse gas and pollutant emissions rules, and energy efficiency regulations.

This additional Rhodium Group modelling is based on draft rules which have not yet been finalised and are subject to change, as well as to potential legal challenge, as discussed above.

The uncertainty shown for the “Trump” and “Biden” scenarios corresponds to the range in the six economy-wide models from Bistline et al. (2023).

Carbon Brief’s analysis does not include any additional post-2025 climate policies that could be adopted by a second Biden administration. Nor does it include the potential impact of pro-fossil fuel policies that could be introduced by a second Trump administration.

Finally, it also does not include additional subnational climate policies that could be introduced, nor does it consider the risk that current or future state action could be hit by federal or legal challenge.

Historical US greenhouse gas emissions are taken from the US EPA inventory through to 2021. Figures for 2022 and 2023 are based on estimated annual changes from the Rhodium Group.

The post Analysis: Trump election win could add 4bn tonnes to US emissions by 2030 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Trump election win could add 4bn tonnes to US emissions by 2030

Climate Change

UN report: Five charts which explain the ‘gap’ in finance for climate adaptation

Developing countries are receiving just a fraction of the international finance they need to prepare citizens and adapt infrastructure for escalating climate impacts.

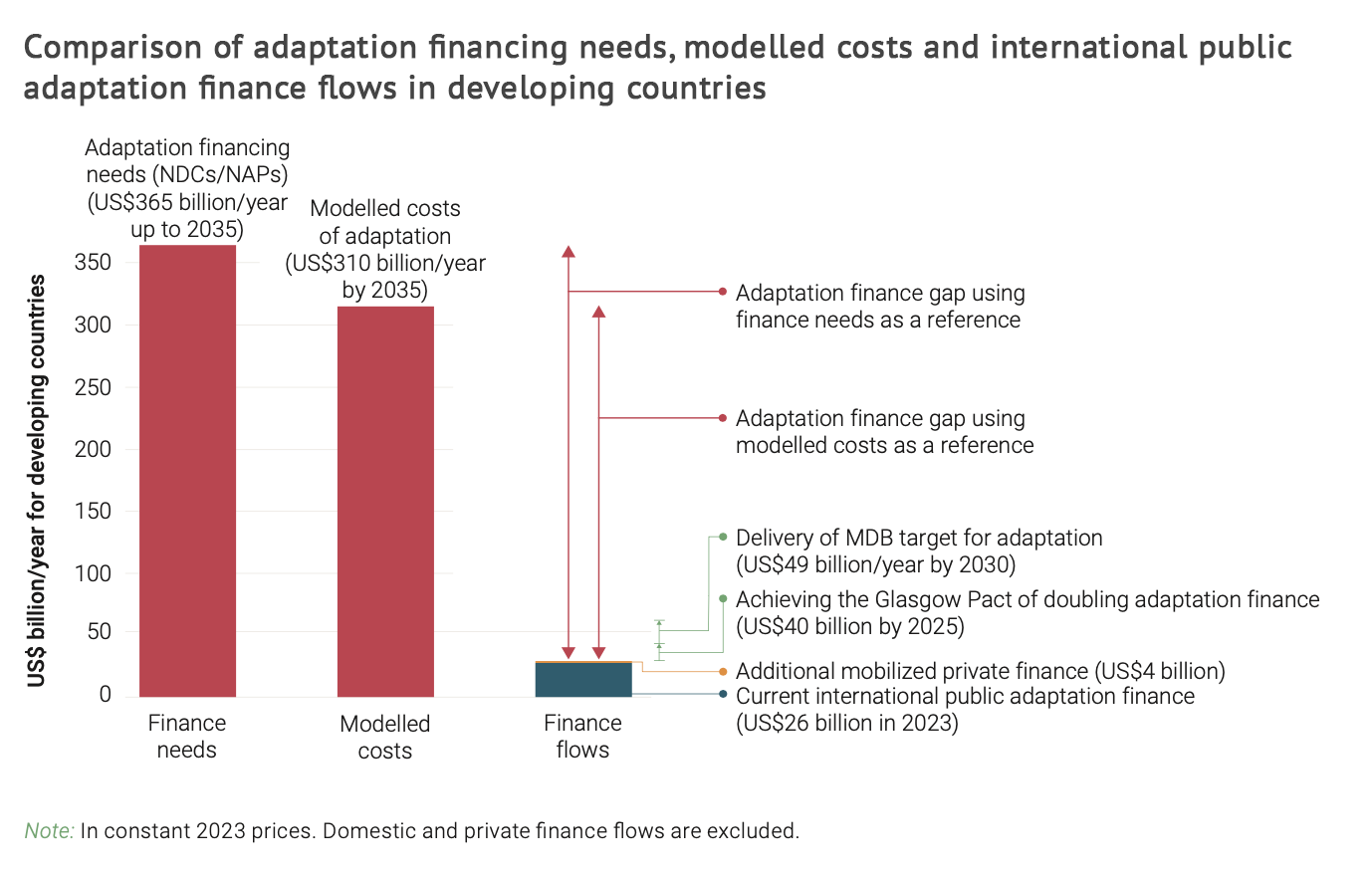

That is according to the latest adaptation gap report from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), which calculates that developing nations will need more than $310bn annually between now and 2035 to prepare for the impacts of climate change.

And yet, in 2023, developed nations provided just $26bn in international adaptation finance to developing nations, according to the report.

UNEP warns that, under current trends, developed nations are on track to miss their goal – agreed at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow – of doubling 2019 international adaptation finance by 2025.

It cautions that countries’ more recent climate-finance pledge for 2035 – the new collective quantified goal (NCGQ) – will be “insufficient” to meet adaptation finance needs.

The UN report – entitled, “Running on empty: The world is gearing up for climate resilience without the money to get there” – also explores how countries are integrating adaptation priorities into national climate plans, policies and practices.

It finds that 87% of countries have at least one national adaptation plan or strategy in place, but warns that gaps remain in the implementation of measures.

Inger Andersen, the executive director of UNEP, says: “Even amid tight budgets and competing priorities, the reality is simple: if we do not invest in adaptation now, we will face escalating costs every year.”

Below, Carbon Brief summarises some of the key takeaways from the report.

- Developed countries are on track to miss their 2025 adaptation finance goal

- Developing nations’ adaptation finance needs are 12 times greater than current flows

- A majority of countries have a national adaptation plan or strategy in place

- Implementation of adaptation measures is progressing – but gaps remain

- The NCQG is insufficient on its own to meet adaptation finance needs

Developed countries are on track to miss their 2025 adaptation finance goal

Climate change adaptation refers to a range of measures that reduce society’s and infrastructure’s vulnerability to climate change, from planting crop varieties that can withstand greater heat through to building stronger defences against floods.

Spending from the public funds of developed nations is a key source of finance for these actions in developing nations, especially for low-income countries that are vulnerable to climate impacts.

Under Article 9 of the Paris Agreement, developed countries agreed to achieve a “balance” in the amount of climate finance raised for emissions reduction and adaptation. However, more money has been raised for cutting emissions than preparing for climate impacts.

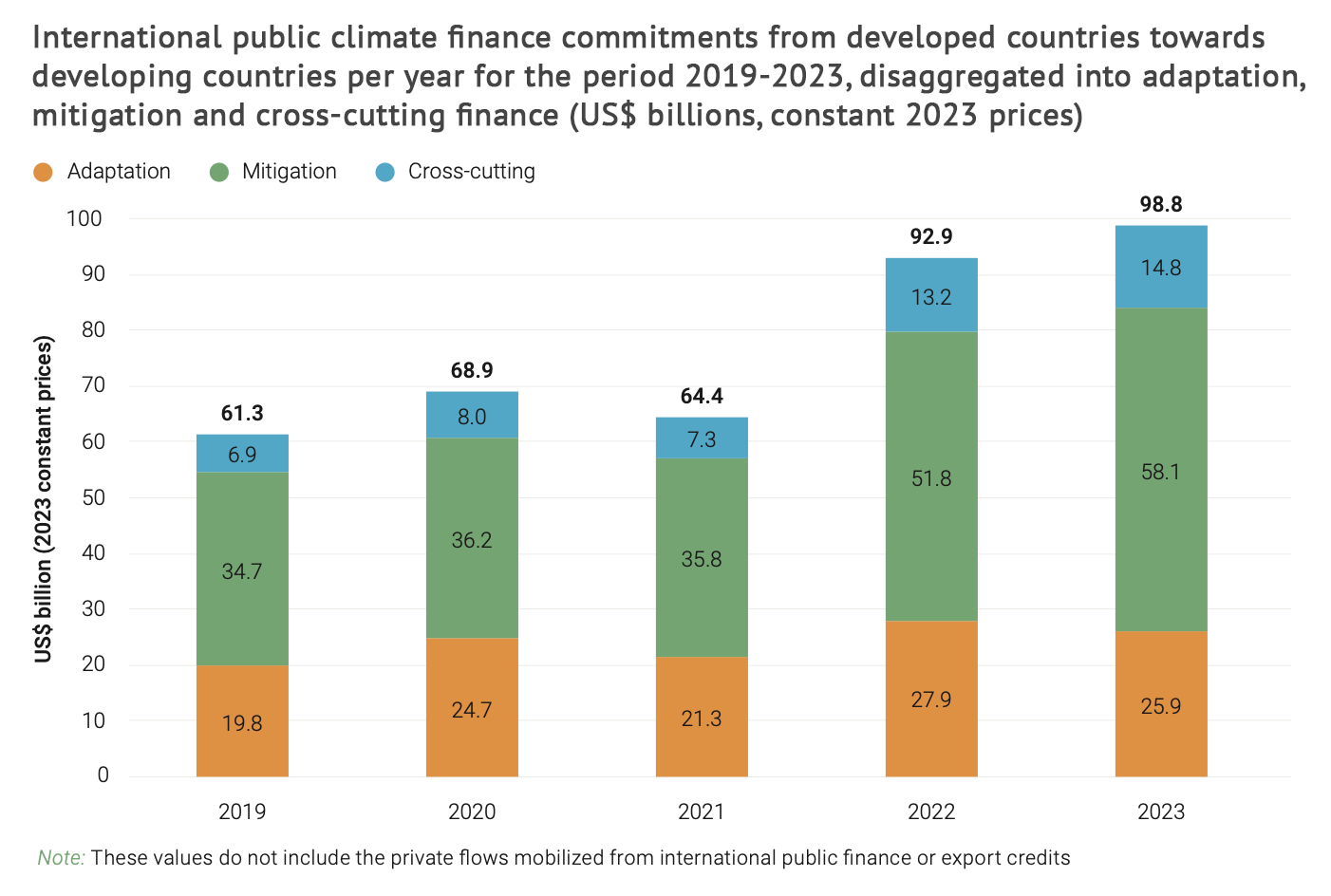

UNEP’s adaptation gap report notes that, in 2023, the amount of public money channelled to developing countries from richer nations for adaptation measures fell.

In total, developed countries raised $25.9bn in international adaptation finance – marking a decline on the $27.9bn recorded in 2022.

The report authors attribute the fall to a decline in funding from multilateral development banks, such as the World Bank, which provided more than half – 57% – of international adaptation finance.

The table below shows how adaptation finance provided by developed countries for developing countries (orange) dipped in 2023 – despite an uptick in climate finance as a whole.

The UN warns that, if current trends continue, developed nations are set to miss their goal of doubling 2019 adaptation finance flows by 2025.

This goal – set out in the Glasgow Climate Pact agreed at the COP26 climate summit in 2021 – commits developed nations to providing $40bn in adaptation funding for developing nations by 2025.

Official climate-finance figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for 2025 will not be available for several years. However, the report notes that, over 2019-23, international adaptation finance grew at a compound rate of 7% – falling short of the 12% rate required to meet the Glasgow Climate Pact goal.

Cuts to international aid budgets since 2023 are also threatening the Glasgow Climate Pact goal, according to the report authors. They note that, globally, foreign aid fell by 9% in 2024 and predict that reductions announced in 2025 are “likely” to lead to a further 9-17% decline.

Meanwhile, countries’ more recent pledge to help raise $300bn a year by 2035 for both tackling and adapting to climate change – set out in the new collective quantified goal for climate finance (NCQG), agreed last year at COP29 in Baku – is also under threat, according to the report.

In the introduction of the report, UNEP’s Anderson writes:

“While the numbers for 2024 and 2025 are not yet available, one thing is clear: unless trends in adaptation financing do not turn around, which currently seems unlikely, the Glasgow Climate Pact goal will not be achieved, the NCQG will not be achieved and many more people will suffer needlessly.”

‘Adaptation investment trap’

The report also breaks down international adaptation finance in 2023 by funding type. It finds that that 70% was either grants, which allow countries to address climate impacts without exacerbating debt, or “concessional” loans, which are provided at below market rate.

However, it notes that “non-consessional” finance – which is provided at, or near, market rates – is on the rise, growing at an annual compound rate of 7% over 2019-23. In 2023, non-concessional loans exceeded concessional ones for the first time, the report notes.

The “increasing proportion” of non-concessional finance raises “long-term affordability and equity” concerns, the authors warn. They also point to the risk of an “adaptation investment trap” – whereby rising climate disasters increase developing countries’ “indebtedness”, which subsequently makes it harder for them to invest in adaptation.

The report also finds that loans and other forms of “debt instruments” comprised “58% on average” of international adaptation finance in 2022-23.

The NCQG text highlights the need for “concessional” and “non-debt creating” finance.

(This came after strong calls from many developing countries to exclude “non-concessional” loans – which result in wealth flowing back to the donor countries as loan repayments and interest – as a form of climate finance. Analysis has shown that many developing countries are spending more on servicing debts than they receive in climate finance.)

Elsewhere, the authors also find that funding for new adaptation projects through UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) funds (the adaptation fund, green climate fund (GCF) and the least developed countries fund (LDCF) and special climate change fund (SCCF) managed by the Global Environment Facility) saw a “large spike” in 2024, with grants reaching around $920m.

However, they note that the recent increase “may not be a trend, with financial constraints likely to rise beyond 2025”.

Developing nations’ adaptation finance needs are 12 times greater than current flows

While previous UN adaptation gap reports have investigated adaptation finance shortfalls through to 2030, this latest analysis extends its estimates through to 2035.

This is in light of the NCQG, which states that developed countries should “take the lead” in raising “at least $300bn” a year for climate action in developing countries by 2035.

The report calculates that the costs of adaptation by 2035 for developing countries sit in a “plausible central range” of $310-365bn annually. It explains that it has arrived at this range based on “two lines of evidence”:

- A modelled estimate of the additional costs of adaptation, calculated using “global sectoral models with national-level resolution”. This exercise pins the cost of adaptation for developing countries at $310bn a year by 2035 under an intermediate emissions scenario.

- An analysis of the climate finance needs set out by developing countries in 97 national adaptation plans and nationally determined contributions (NDCs) submitted to the UNFCCC – with “extrapolation” of this data to all 155 developing countries. This results in the upper figure of $365bn per year up to 2035.

The chart below shows the disparity between existing finance flows (dark blue bar) and adaptation finance needs and modelled costs (red bars).

With current levels of international adaptation finance estimated at $26bn a year, the report calculates that developing countries are facing an “adaptation finance gap” in the range of $284-339bn per year by 2035.

As such, it calculates that the adaptation finance needs of developing countries by 2035 are “12-14 times” as much as current finance flows.

Of the public adaptation finance that has been issued, a higher proportion currently goes to the countries most exposed to climate hazards, according to the report. It notes that, in 2022-23, $10.4bn and $1.2bn was allocated to least-developed countries (LDCs), including Afghanistan and Rwanda, and small island developing states (SIDS), such as Tuvalua and the Marshall Islands, respectively.

Nevertheless, finance provided to these climate-vulnerable nations is still “modest relative to needs”, the report warns. It estimates that the adaptation finance needs of LDCs and SIDS are $50bn a year.

It also finds that per-capita adaptation finance to both country groups was lower in 2022-23 than previous years, at $9 for LDCs and $20 in SIDs.

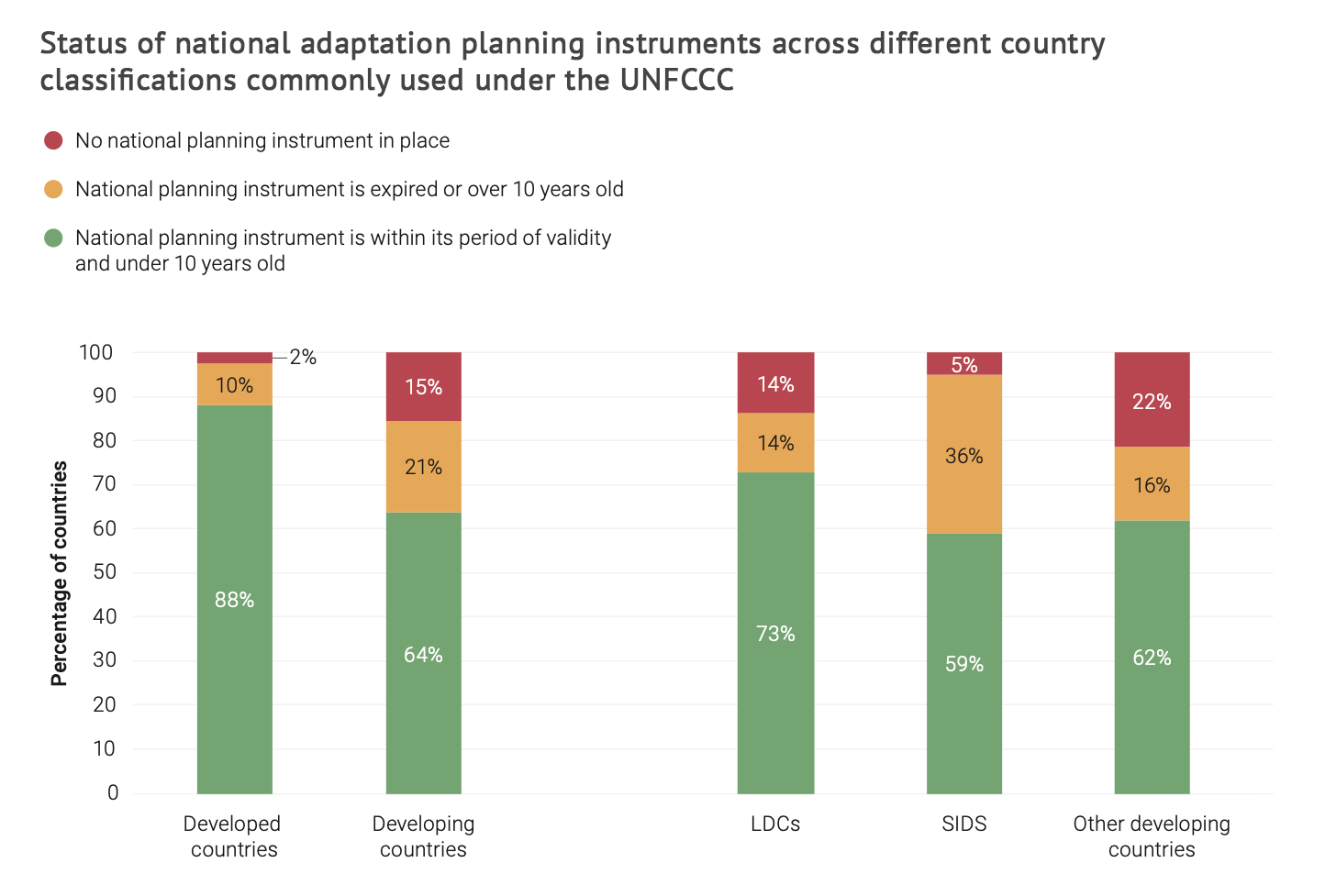

A majority of countries have a national adaptation plan or strategy in place

Under the framework for the global goal on adaptation agreed at COP28, countries said they would put in place “national adaptation plans, policy instruments and planning processes and/or strategies” by 2030.

To assess the “global status” of national adaptation planning, the authors of the report tracked the publication of national plans, strategies and policies for adaptation in each country.

According to the report, the first national adaptation policy was published in 2002. It finds that there was a “notable acceleration” in countries developing national adaptation planning instruments over 2011-21, but says that, since then, progress has “slowed significantly”.

According to the report, 87% of countries had at least one national adaptation policy, strategy or plan in place as of 31 August 2025. However, 36 of these 172 countries’ plans are “expired” or “outdated”.

Meanwhile, 25 countries had no national adaptation plan at all, according to the report. It explains that these are “predominantly developing countries, suggesting that financial, technical and human resource constraints inhibit national adaptation planning”.

Of these countries without plans, 21 have “initiated a process to develop” a national adaptation plan, according to the report. However, it notes that many of these countries have “been in this process for a long time”.

The chart below shows the percentage of countries from different “country classifications” that have no national adaptation planning instrument in place (red), an expired adaptation planning instrument in place (yellow) and a valid instrument in place (green).

The report also discusses different types of adaptation “mainstreaming”. This is defined by the report authors as the “integration of adaptation objectives and climate risk considerations into the established functions, policy and practice of government institutions to build climate resilience”.

The authors list six different mainstreaming strategies. For example, “directed” mainstreaming means “dedicating funding, staff capacity-building and resources specifically to adaptation, including through financial frameworks and fiscal processes such as budget planning”.

Another example is “regulatory mainstreaming”, which means “modifying the formal or informal policy instruments such as legislation, frameworks, strategies and plans by integrating adaptation”.

According to the report, only regulatory mainstreaming is captured by the framework for the global goal on adaptation’s target related to planning.

The report also outlines the different “levels” of mainstreaming. These range from “prioritisation”, which it describes as a strong level of mainstreaming in which adaptation takes precedence over existing policy goals, to “coordination”, in which adaptation “is recognised as a policy goal, but is secondary to existing priorities”.

However, the report says there is “presently no agreement on how to measure and assess the outcomes of mainstreaming”.

Implementation of adaptation measures is progressing – but gaps remain

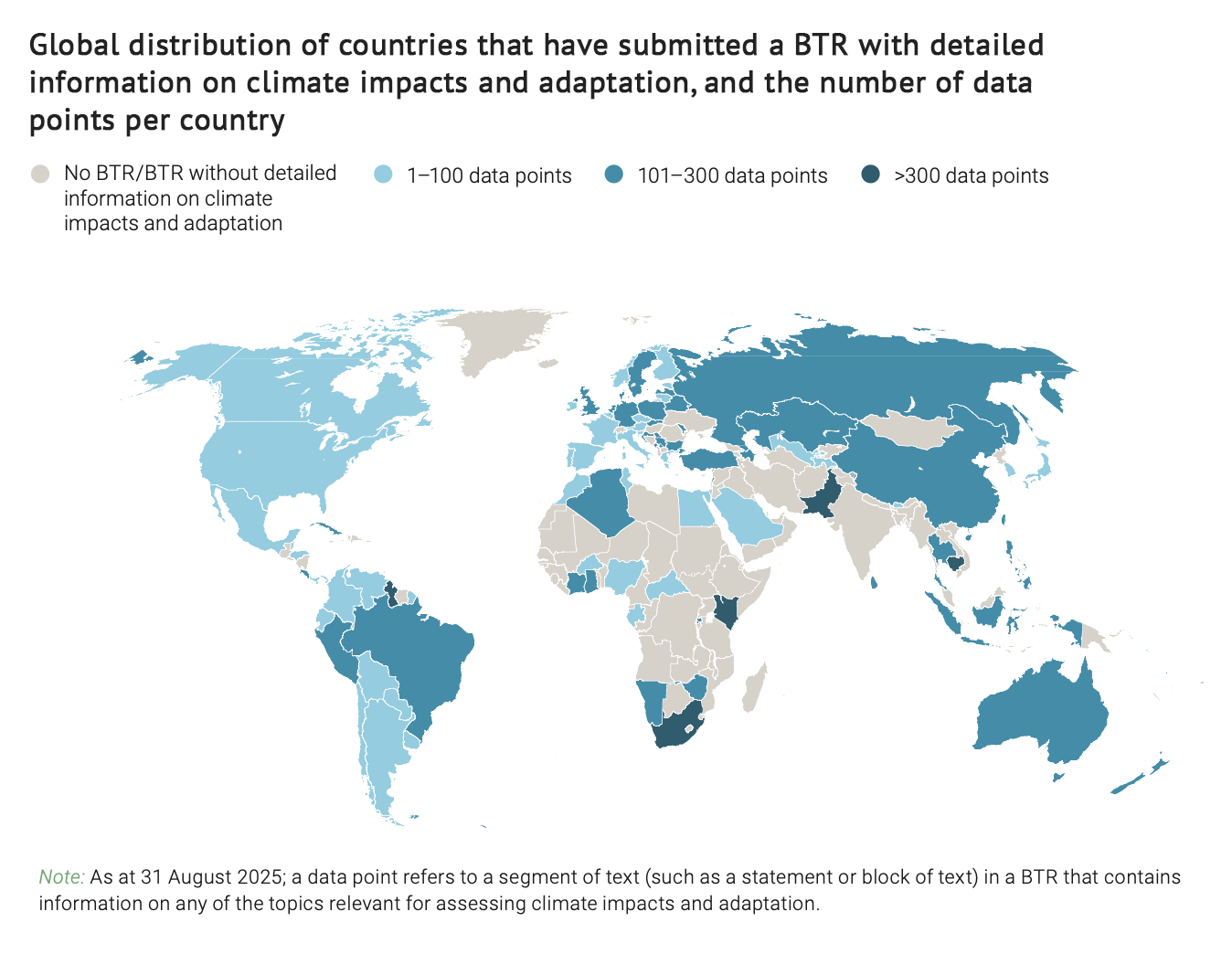

Under the UN “enhanced transparency framework”, countries are required to submit information about their climate progress in biennial transparency reports (BTR). The first report was due at the end of 2024.

The adaptation gap report calls BTRs the “most comprehensive national source of information on adaptation implementation worldwide available”.

The report says that 105 countries had submitted BRTs as of 31 August 2025, of which 94 include details about adaptation

The authors find that 75 of these BTRs mention gender in relation to adaptation. However, only 4% of the results reported through BTRs are directly related to “gender and social inclusion”.

The report also highlights the “uneven coverage” of BTRs globally. According to the report, 88% of developed countries have submitted a BTR, compared to only 37% of developing countries.

It adds that there are further inequalities within the bracket of “developing countries”. Only 21% of SIDS and 14% of LDCs have submitted BTRs with “detailed information on climate impacts and adaptation”, according to the report.

This could “indicate that preparing national reports such as BTRs is most burdensome for the countries with the least capacity”, the report authors suggest.

The map below shows the countries that have submitted a BTR including “detailed information on climate impacts and adaptation” (blue) and those that have not (grey). For the former category, darker blue indicates that the country’s BTR includes more segments of text (data points) about climate impacts and adaptation.

The report finds that countries are “disproportionately reporting on climate hazards, systems at risk, climate change impacts and adaptation priorities” in BTRs. Meanwhile, only 15% and 7% of the data points in the map above discuss adaptation “actions” and “results” respectively.

In total, the report identifies 1,640 “adaptation actions” across 68 BTRs. It says that 23% of these are related to “biodiversity and ecosystems”, 18% to “infrastructure and human settlements”, 16% to “water and sanitation” and 14% to “food and agriculture”.

However, it finds that actions targeting health and poverty alleviation or livelihoods are each accounting for only 5%, while those addressing cultural heritage are “nearly absent” and account for less than 1% of all reported actions.

In a separate analysis, the report explores documents submitted by developing countries to the UNFCCC to understand how adaptation needs break down by sector. It finds that the 55 plans submitted by developing countries which include “detailed sectoral information” reveal that the agriculture and food sector and water supply are “common priorities across all regions, though they vary in terms of their relative importance”.

The NCQG is insufficient on its own to meet adaptation finance needs

At COP29 last year, developed nations pledged to raise at least $300bn per year under the NCQG for both mitigation and adaptation.

The report says that, although the target “appears significantly higher than the previous goal for developed countries to mobilise $100bn by 2020 for developing countries”, it is still “clearly insufficient” to meet adaptation finance needs in 2035.

The report sets out two reasons for this.

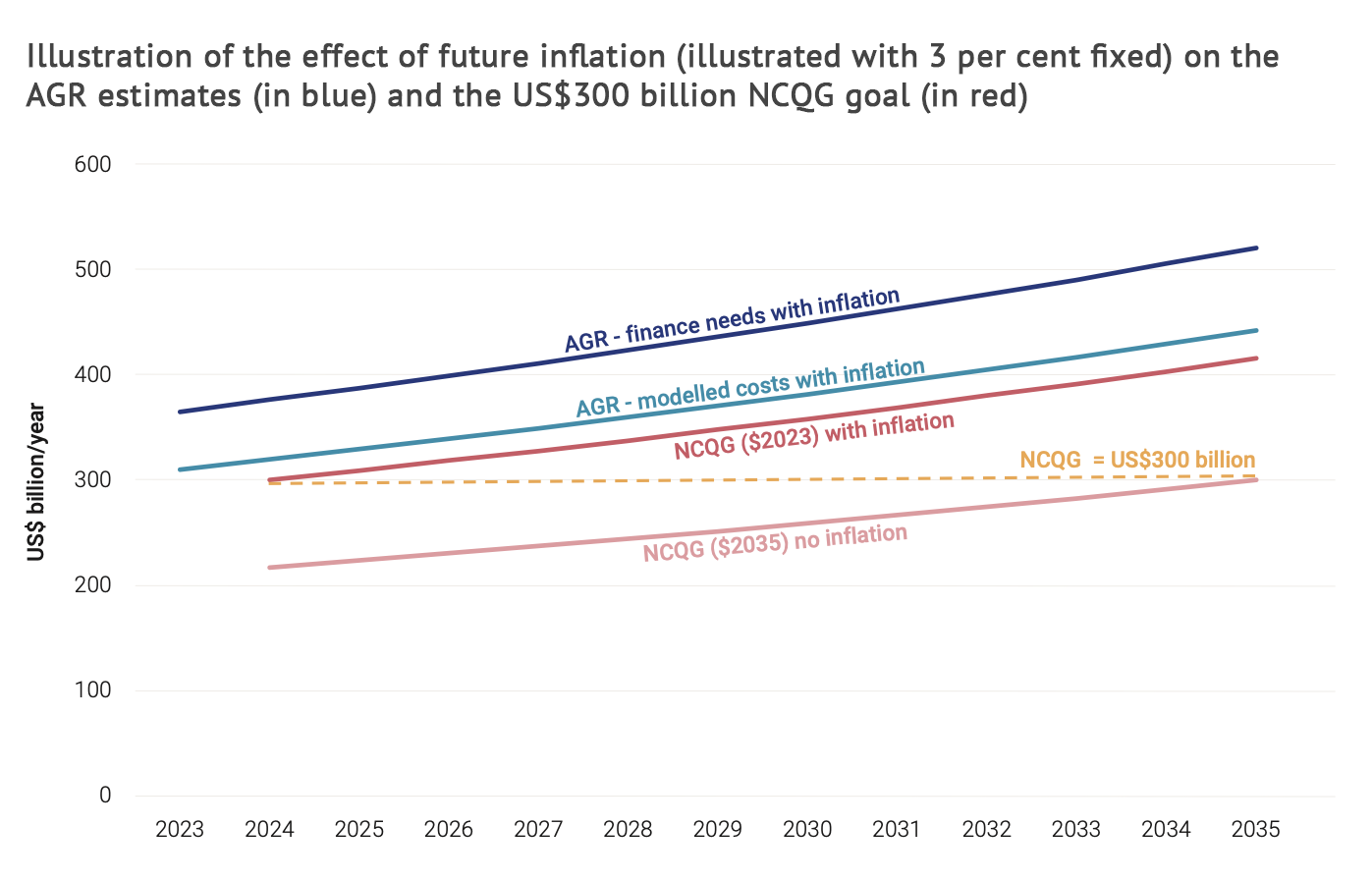

First, the authors explain that the $300bn target is not adjusted for inflation. It says that adaptation costs for developing countries are currently estimated at $310-365bn annually until 2035, based on costs in 2023. However, when adjusting for an inflation rate of 3% per year for the next decade, this number rises to US$440–520bn by 2035.

(In an analysis published last year, Carbon Brief noted that the $300bn target does not account for inflation.)

The plot below shows the effect of inflation on adaptation finance needs (dark blue) and modelled costs (light blue). It also shows the NCQG goal, accounting for inflation, based on 2023 costs (red) and without inflation based on 2035 costs (pink). It also shows the NCQG goal of $300bn by 2035 (yellow).

Second, it notes that the NCQG covers both mitigation – namely, efforts to cut emissions – and adaptation. So far, it warns that no “subgoal” has been agreed to determine how much money goes to each.

The report authors have also developed two scenarios exploring how much the NCQG would bridge the adaptation finance gap, if the $300bn target is met, both of which account for inflation. These are:

- A “minimum adaptation scenario”. The authors assume that 26% of the NCQG money will be used for adaptation finance as this is the percentage of all international climate finance that was spent on adaptation over 2011-20. Based on historical proportioning of finance, $3bn of the resulting $78bn this would go to SIDS and the rest to $25bn to LDCs.

- A “maximum adaptation scenario”. Under this scenario, the Glasgow Pact and Baku to Belém Roadmap are achieved, meaning that adaptation funding reaches $40bn annually by 2025 and $120bn annually by 2030. They also assume that adaptation finance grows by 7% per year, reaching $166bn by 2035 – more than half of the NCGQ finance goal of $300bn. Under this scenario, SIDS would receive $6bn in adaptation funding by 2035 and LDCs would receive $55bn.

The report concludes that, even if the NCQG is achieved, a “significant adaptation finance gap” is likely to remain in 2035 “regardless of the share of international public climate finance that will flow towards adaptation”.

Meanwhile, the report notes that private-sector finance can help “fill the adaptation finance gap” – but cautions that its overall contribution is likely to be “modest”.

The “realistic” potential for private-sector investment, according to the report, is $50bn per year by 2035 – a figure it estimates would cover 15-20% of overall estimated needs.

Reaching this level of private-sector finance will require “targeted policy action” given that current private-sector flows to “publicly identified” adaptation priorities in 2023 are estimated at $5bn, it notes.

Furthermore, UNEP warns that many proposed approaches for raising private-sector funds for adaptation measures pass “most of the costs of adaptation back to developing countries or households”.

The post UN report: Five charts which explain the ‘gap’ in finance for climate adaptation appeared first on Carbon Brief.

UN report: Five charts which explain the ‘gap’ in finance for climate adaptation

Climate Change

AI is Decoding Whales’ Language. Could That Be a Turning Point in the Push for Their Rights?

The Cetacean Translation Initiative (CETI) is using artificial intelligence to help understand sperm whale communications. Lawyers think the discoveries could galvanize the world to recognize whales’ legal rights.

For centuries, humans have drawn a line between themselves and other species, initially claiming that other animals couldn’t feel pain. Science proved they could. Then the argument shifted: Animals lacked consciousness or the ability to think in complex ways. That, too, fell apart under mounting evidence. Now, a final frontier is language—the belief that only humans possess it.

Even that line is beginning to blur.

With the help of artificial intelligence, robotics and new recording technologies, scientists are edging closer to decoding the vocalizations of elephants, whales and other animahttps://insideclimatenews.org/news/29102025/ai-sperm-whale-communications-legal-rights/

Climate Change

In a ‘Disheartening’ Era, the Nation’s Former Top Mining Regulator Speaks Out

Joe Pizarchik, who led the federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement from 2009 to 2017, says Alabama’s move in the wake of a fatal 2024 home explosion increases risks to residents living atop “gassy” coal mines.

Joe Pizarchik knows mining.

In a ‘Disheartening’ Era, the Nation’s Former Top Mining Regulator Speaks Out

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change3 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Greenhouse Gases3 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change1 year ago

Climate Change1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy4 months ago

US Grid Strain, Possible Allete Sale