Andreas Sieber is the associate director of global policy and campaigns at 350.org.

It is no accident that the COP30 presidency convenes consultations on Thursday, a day after the UN Climate Summit. Wednesday’s speeches offered proof that, even amid geopolitical upheaval, the Paris Agreement still drives momentum. At the same time, the hard truth was clear well before the summit: the pledges do not add up.

COP30’s credibility rests on how it confronts this ambition gap. Attempts to spin COP30 as a success without such a response seem hollow. If COP30 must respond to this ambition gap, a cover decision emerges as the most credible path forward.

COP30 brings the ambition cycle of the Global Stocktake (GST), launched at COP28, to a close. The ambition gap is often framed through the temperature threshold, but it runs deeper, encompassing adaptation, loss and damage, and finance, all of which are falling dangerously short.

Countries trail COP30 clash over global response to shortfall in national climate plans

A cover decision is surely not the only marker of success: the Belém Action Mechanism on Just Transition, an ambitious Baku-to-Belém roadmap, and a Global Goal on Adaptation are just a few among other high-stakes deliverables. But it is one decisive piece of the puzzle.

Breaking through entrenched negotiations

Why do we need one in the first place? Anyone who sat through the UAE Dialogue or Mitigation Work Programme earlier this year, will have more than serious doubts that these rooms can overcome their entrenched dynamics to deliver adequate outcomes, let alone allow the broader dealmaking required.

That is why a cover decision emerges as the most credible way to confront the ambition gap head-on – and here it is the Brazilian presidency that holds the pen.

A cover decision is no magic bullet to solve negotiation challenges, but it offers the best-placed procedural vehicle to balance different elements of the ambition package, allowing a race to the top instead of zero-sum trade-offs.

At the last COP, we saw mitigation pitted against finance, and without real commitments – especially credible new finance from wealthy countries – that history risks repeating itself. Process alone is no guarantee of success, but a misguided process is a recipe for failure. It’s also noteworthy that the COP29 presidency, due to a lack of political will or misguided strategy, refused to engage with the idea of a cover decision.

Instead of discussing several crunch issues across different rooms, a cover decision can bring topics together in the same room and the same text.

What should a cover decision include

A cover decision can anchor critical finance outcomes that otherwise lack a formal home, from the Baku-to-Belém roadmap to a meaningful scale-up in adaptation finance, with tripling as the obvious first step.

This is not about creating a procedural parking lot; it is about giving key outcomes real political and procedural weight. Linking the roadmap’s $1.3 trillion mobilisation goal for 2035 to concrete donor commitments through a cover decision would turn aspiration into accountability.

Responding to the ambition gap will also require initiatives that target the sectors driving the crisis. This could mean establishing a dedicated working group on phasing out fossil fuels, anchored in equity and 1.5°C consistent timelines, with a mandate that connects its work to COP31 under the incoming Presidency.

Brazil’s environment minister suggests roadmap to end fossil fuels at COP30

It could also mean reinforcing and expanding the COP29 Grids Initiative, this time with concrete public finance commitments attached. Both initiatives could be launched through presidential declarations and then captured and formalised within a cover decision.

Finally, a cover decision must also speak beyond the negotiating halls. It should respond with grave concern to the latest NDC synthesis report, and it should build on messages from the landmark ICJ advisory opinion and the leaders’ summit to signal that the world’s governments understand the urgency of the moment.

Instruments of real progress

Critics may dismiss cover decisions as the epitome of empty words: procedural theatre about brackets and commas, offering conversation to those who are excited about “the process”, conversation rather than consequences. At times, cover decisions can be sprawling, jargon-laden texts that feel detached from real-world impact, such as in 2019. Yet history shows they can also be instruments of real progress.

It was a cover decision in Durban in 2011 that launched the Ad Hoc Working Group (ADP), the negotiating track that ultimately delivered the Paris Agreement.

Since then, their character has evolved. With the Paris rulebook now in place, cover decisions have increasingly driven forward momentum.

In Glasgow, a cover decision broke new ground by naming a fossil fuel for the first time, calling for the “phase down” of coal. However imperfect – singling out coal was very convenient for European countries and the United States at the time – this opened the door to COP28’s landmark outcome: a collective commitment to transition away from all fossil fuels and to triple renewable energy.

One could argue that the COP28 Global Stocktake decision was not technically a cover decision, but in practice it served as one. And in Egypt, a cover decision launched both the Just Transition Work Programme and the loss and damage fund, breakthroughs that continue to shape the process today. As we look ahead to COP30, where the Belém Action Mechanism on Just Transition is on the table, history suggests that a strong cover decision could again prove decisive.

COP30 and the Brazilian presidency will be remembered for whether (and how) it responds to the ambition gap in this decisive decade. A strong cover decision remains the most credible tool to anchor that response.

The post Why COP30 needs a cover decision to succeed appeared first on Climate Home News.

Climate Change

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of America’s Broken Health Care System

American farmers are drowning in health insurance costs, while their German counterparts never worry about medical bills. The difference may help determine which country’s small farms are better prepared for a changing climate.

Samantha Kemnah looked out the foggy window of her home in New Berlin, New York, at the 150-acre dairy farm she and her husband, Chris, bought last year. This winter, an unprecedented cold front brought snowstorms and ice to the region.

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of the Broken U.S. Health Care System

Climate Change

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Two Utah Congress members have introduced a resolution that could end protections for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Conservation groups worry similar maneuvers on other federal lands will follow.

Lawmakers from Utah have commandeered an obscure law to unravel protections for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, potentially delivering on a Trump administration goal of undoing protections for public conservation lands across the country.

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Climate Change

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

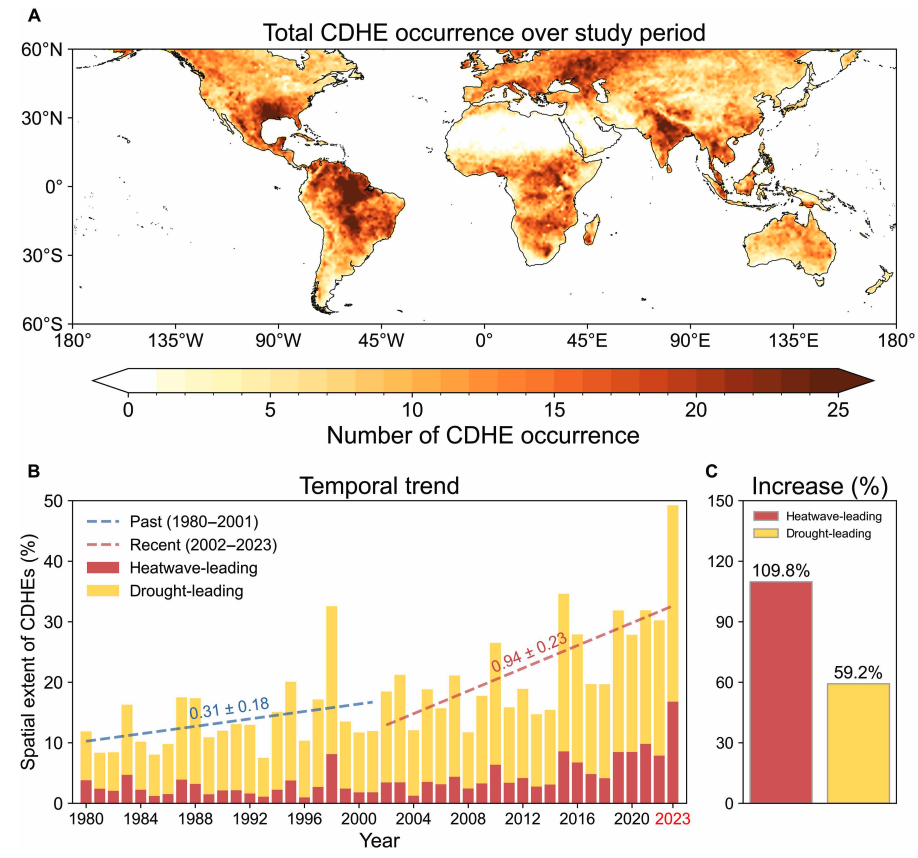

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits