The ICYMARE conference in Bremen

Hi, my name is Josephine, I am a student in the Master’s program Biological Oceanography at Geomar Helmholtz-Center for Ocean Research. I am currently writing my Master’s thesis at the Research and Technology Center (FTZ) in Büsum, which is part of Kiel University. My research focuses on the diversity and composition of fish communities in tidal creeks of the German Wadden Sea. My thesis is part of a project that consists of a field survey where fish and benthic communities were sampled at two locations in the Wadden Sea between May and November 2024.

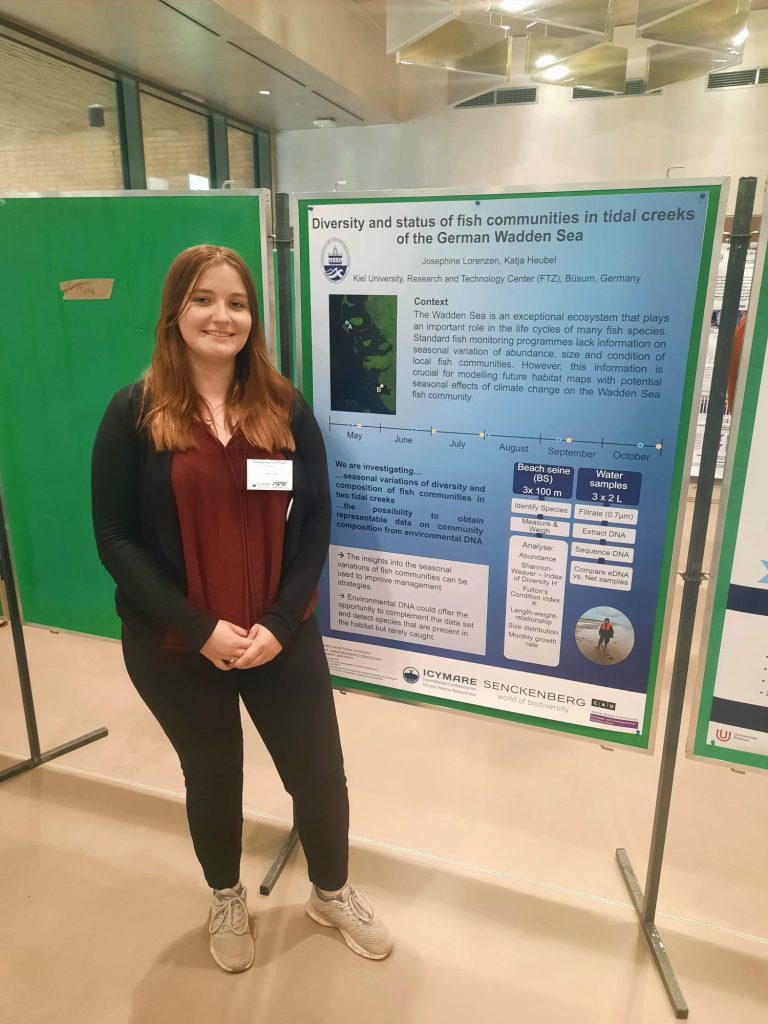

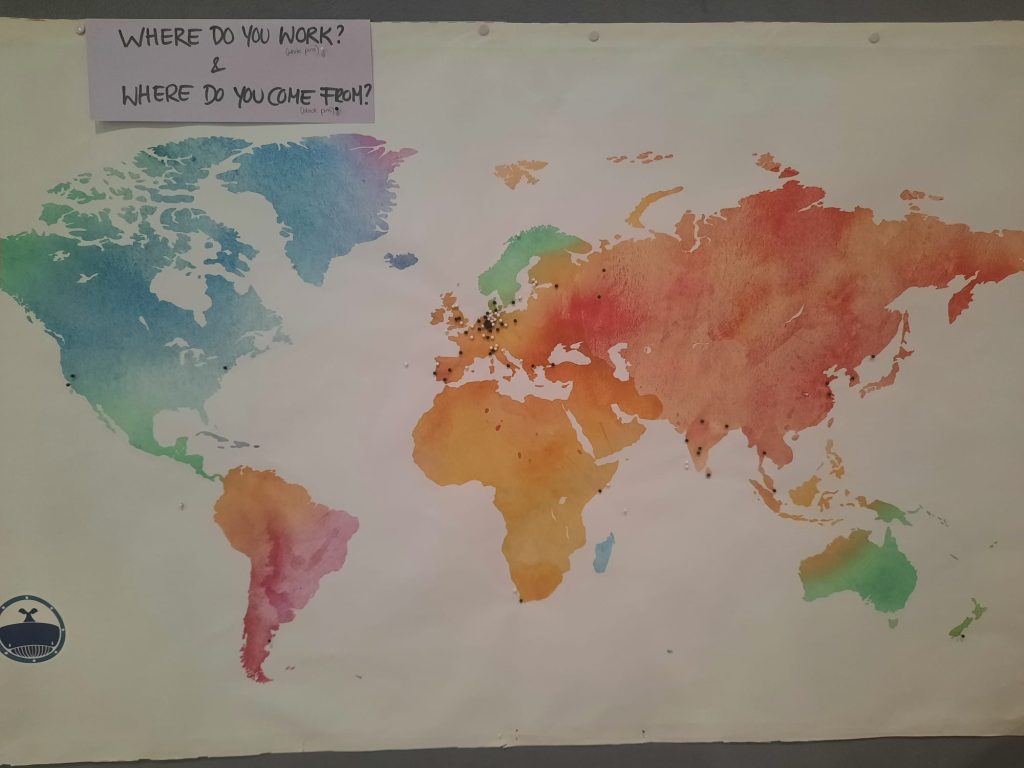

The FYORD travel grant made it possible for me to attend the ICYMARE conference in Bremen, where I presented my research plan in a poster session. The conference took place from September 15th to 20th and generally addresses early career researchers in the field of marine sciences. Most of the participants were PhD students, some recently graduated Postdocs and some master students. The conference started with a get-together for drinks and snacks at the Bremen Overseas Museum and was followed by four days full of interesting talks, a poster session, excursions and ended with a big party. Each day started with a keynote talk held by experienced scientists. What I really enjoyed about this was that most of the talks were interactive and presented a range of career options following a degree in marine sciences. I really had the impression that all these talks were conceptualized to provide guidance, valuable insights and reassurance to young researchers like me. My favorite keynote talk was about merging “Constructive Journalism” and Research for the Greater Good by Christoph Sodemann from the company Constructify.Media, mostly because I have never heard of the concept of “Constructive Journalism”, and I feel like that is exactly what the world needs more of right now. The rest of the day was filled with a variety of presentations, always in two parallel sessions, so that there was always an interesting talk to listen to. There were coffee breaks and a lunch break each day, where you could network or take a look at the posters or enjoy some time in the creative corner, where you could express your passion for marine science and more in little artworks for everyone to see or for you to take home. Every day after lunch, there was a so-called “round table”, where we could hear and talk about topics that are important to us, for example, mental health during a PhD or how to handle conflicts at your workplace.

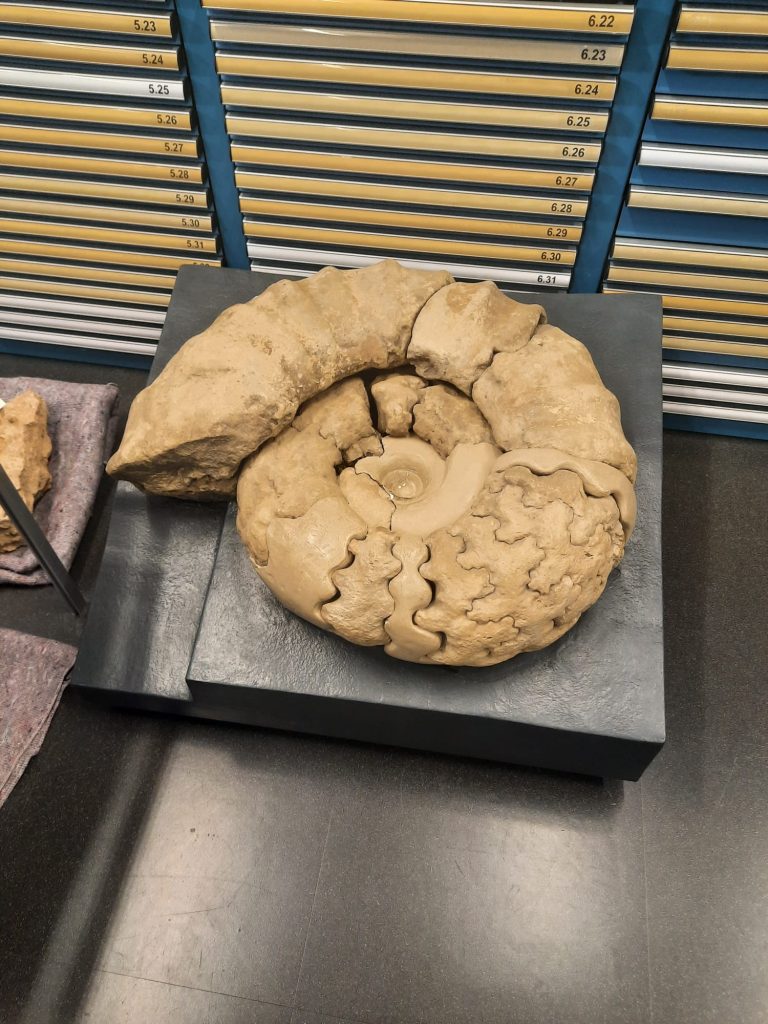

On the second day of the conference, the evening was reserved for the poster session, where I got to present my research for the first time alongside approximately 30 other young scientists. Each presenter was standing next to their poster, ready to answer questions or guide you through the poster. It was a great experience and made me feel more confident about my research. I got to talk to many people, some who work on similar projects, or some who come from a completely different background. This way, I learned how to adjust my presentation to the person who is listening based on what questions they ask. And while it was very exciting, I was also telling the same story over and over again to different people until after two hours of talking, my throat hurt, and I decided to take a look at the other posters and presenters before I headed back to my hostel. The afternoon of the third day was reserved for workshops and excursions. The workshops introduced either technologies, for example for pCO2, pH or acoustic measurements, or aimed to improve skills such as navigating peer review processes or introduced different paths, for example as a data scientist or scientific journalist. I decided to go on one of the excursions that was highly recommended to me, the guided tour through the MARUM, the Bremen core repository of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) and the Geosciences Collection of the University of Bremen. For the evening, a Science Speed Meeting was organized where you could meet other scientists and possibly make some new friends. On Friday evening, the conference was then closed with a Farewell and a Post-Conference Party.

Overall, this was a great experience that increased my confidence in my research and career choice, gave me the opportunity to meet many great people and to gain insights into what is possible after I graduate. What makes this conference so special is that it is mostly organized by young scientists for young scientists, which is reflected in the structure of the conference and the price tag, making it accessible to students. I am definitely going to be in Bremerhaven for the ICYMARE 2025. If you, the reader, are standing at the beginning of your career in marine research, I would highly recommend you come, too.

Josephine Lorenzen

Sea-Level Rise and Vulnerability in Seychelles

My name is Kim Nierobisch. During my studies, I developed a focus on interdisciplinary marine science, completing a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science/Sociology and a Bachelor of Science in Geography, both with a strong emphasis on marine topics. Currently, I am pursuing my Master’s degree in Practical Philosophy of Economy and Environment.

Climate and coastal adaptation planning often operate within a more technical framework, while social, political, cultural, and normative dimensions tend to be sidelined. Beyond the question of who decides where and to what extent adaptation occurs, the normative dimension plays a fundamental role – namely, the essential question of what coastal communities define as worth protecting. My master’s thesis explores the intersection of sea-level rise and vulnerability in Seychelles. Specifically, I analyze how normative values shape coastal adaptation priorities by examining government documents to identify both explicit and implicit strategies. In this context, normative values are understood as collectively held beliefs about what should be prioritized, preserved, or pursued. They reflect societal judgments about what is considered good, just, or desirable. During the workshop, I had the opportunity to reflect on these findings. As part of a focus group discussion, I explored the normative dimension of coastal adaptation priorities more deeply, allowing me to better understand and contextualize normative values, which resonate in decision-making but remain underexamined.

The workshop on Sea-Level Rise Impacts in Seychelles 2024 was organized by the adjust team from Kiel University, the Ministry of Agriculture, Climate Change and Environment (Seychelles), and Sustainability for Seychelles. It brought together stakeholders mainly representing government organizations, environmental consultants, and nature conservation groups. The workshop combined inter- and transdisciplinary approaches to analyze the impacts of sea-level rise in Seychelles, assess coastal adaptation options, and discuss various strategies and priorities.

The process of analyzing and extracting normative values was quite challenging. Although normative values were not explicitly named or fully recognized within a technical dominant framework, they were clearly present and influenced coastal adaptation planning. This underscores the importance of more deeply integrating social, political, cultural, and normative dimensions into research and planning processes. Inter- and transdisciplinary formats have their limits (which should always be defined), but they remain valuable approaches because they provide a more holistic understanding of complex issues. A key takeaway from my experience was understanding that such collaboration requires continuous dialogue and exchange to overcome barriers between different perspectives. It takes a lot of time, effort, and persistence, especially due to the different epistemologies – different ways of knowing and understanding the world, which are shaped by different disciplines, cultures, and experiences – involved.

Additionally, I had the opportunity to strengthen dialogue and cooperation within the UN Ocean Decade framework. The initiative was officially endorsed as an UN Ocean Decade activity, focusing on research and planning that promotes sustainable ocean governance through interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and integrative approaches. As the youngest member of the German UN Ocean Decade Committee, I recognize the urgency of addressing current challenges, such as the 1.5°C target (which is at risk of failing) and the limited progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (with only around 16% expected to be achieved by 2030). Dialogue, particularly among young ocean enthusiasts and early career ocean professionals, is necessary to tackle these challenges and build a sustainable future together. These conversations offered an important opportunity to promote solidarity, mutual support, and shared motivation in a time of uncertainty regarding global climate and ocean-related goals.

THANK YOU! I am deeply grateful for the many meaningful encounters with incredible people, inspiring moments, and the fruitful, critical exchanges that took place in Seychelles. I would like to sincerely thank the FYORD team and the OceanVoices blog for their long-standing support and collaboration.

Kim Nierobisch

The ASLO Aquatic Sciences Meeting

My name is Mariana Hill, and I work at the Biogeochemical Modelling group at GEOMAR. I’ve been at GEOMAR since 2016, when I started my Master’s degree. Currently, I do my own research in collaboration with other members of GEOMAR and institutes overseas. I am interested in modelling higher trophic levels, such as fish, sharks and whales, and their interactions with the environment. For this, I use diverse tools, for example, dynamic models such as the individual-based multispecies model OSMOSE, as well as habitat niche models using statistical and machine learning algorithms. I work with regional models, allowing me to study in detail local ecosystems. For my doctorate, I focused on the northern Humboldt Current System, which hosts the most productive fishery on the planet. During the postdoc, I have expanded my expertise to other ecosystems such as the western Baltic Sea, the North Atlantic Ocean and the Mexican Pacific.

I attended the ASLO Aquatic Sciences Meeting in Charlotte, USA, from the 26th to the 31st of March. I presented our latest work modelling the habitat of Peruvian anchovies in the northern Humboldt Current System. This conference gathers every two years researchers working on ocean sciences and limnology from all over the world. While there’s room in the conference for scientists working in all kinds of aquatic fields, biogeochemistry and marine biology are especially well covered. I presented at the “Leveraging Modelling Approaches to Understand and Mitigate Global Change Impacts on Aquatic Ecosystems” session, which was one of the largest in the conference, spanning a whole day. This session brought together modellers from several disciplines, so I got the chance to learn about new ecological models that I had not heard of, such as the structural casual models. I was also impressed by the level of expertise of some really young scientists, even in their Bachelor’s. I found it an interesting experience that, despite being an early career scientist, in this conference, I took more of a mentoring role for younger scientists in contrast to my previous conferences when I was still a student.

The ASLO conference is very friendly with students and early career researchers, providing plenty of opportunities for these groups, such as workshops on science communication and career development, social events, mentoring and even a mailing list for searching for shared accommodation. I got the chance to reconnect with another Master’s student from GEOMAR who is now working as a postdoc in Arizona and went for a hike in the Appalachian Mountains with some of her friends. The whole experience ended up with being invited to a new working group on Nitrogen. Another non-conventional exchange happened at the parking lot of our accommodation when everyone had to evacuate due to a false fire alarm, and my roommate and I met a senior scientist working in Texas who reminded us of the most basic questions of why we do science. Don’t just write proposals on the hot topics, “do what you love and your time will come”.

ASLO 2019 was the first conference that I attended when I started my doctorate. Back then, I found the possibility of chairing a session at a future conference attractive. Later on, I learnt that this is not such an easy task since you have to look for co-hosts and write a session proposal. However, this year, when I got my letter of acceptance to present at ASLO, I also got an invitation to chair one of the sessions that had been proposed by the organisers but did not have a host yet. I expressed my interest and became the chair of the “Fish and Fisheries” session! This was a very rewarding experience since I got to know the speakers of the session, as well as my co-chair, and I learnt what it is to be “on the other side of the table” during a session. I learnt some useful practices that I will apply from now on whenever I present at a conference session. For example, something I did not use to do but now I consider important is to introduce yourself to the session chair before the session starts. As a chair, I really appreciated this since I could identify the speakers and know if anyone was missing.

Keep an open mind when going to ASLO and step out of your comfort zone to visit not only the sessions related to your main research interest but also other sessions and workshops; you might get nice surprises. It is also a great setting for getting career advice from people who are not so close to you or are not involved in your work. Don’t be scared of talking to senior researchers, I have never encountered a person who is not happy to talk to me during a conference; in the worst-case scenario, you might just need to line up for a couple of minutes, but the time spent waiting is totally worth it! I have got some of the best ideas for my science communication strategies at conferences, from a scientist who was not very comfortable speaking English bringing a buffet of questions about his talk for the audience to pick from, to an improv workshop on how to speak freely and engage with the audience through a positive attitude hosted by a Hollywood actor. Always have a notebook for taking notes with you because your brain will be boiling with new ideas during the whole conference.

I recommend attending the ASLO conference, especially to early career researchers, to biologists and biogeochemists and to anyone looking for collaborations in the USA. A special recommendation for shy scientists is to try different ways of networking, not just the typical chats during the coffee breaks. For example, the icebreakers and mixers usually have specific formats to integrate everyone into small groups. Talking to the person sitting next to you during the plenary session might just get you to meet a top scientist in your field. This is how I got to know about a new project on whale monitoring in the Virgin Islands! Furthermore, asking questions one-to-one to the presenter after the session or plenary is also a great way to start a conversation. And, finally, I totally recommend any early career scientist to host a session; it is a lot of fun and, at least in ASLO, the format is so friendly that it will cost you barely any effort.

Mariana Hill

Ocean Acidification

What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs?

Coral reefs are beautiful, vibrant ecosystems and a cornerstone of a healthy ocean. Often called the “rainforests of the sea,” they support an extraordinary diversity of marine life from fish and crustaceans to mollusks, sea turtles and more. Although reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean floor, they provide critical habitat for roughly 25% of all ocean species.

Coral reefs are also essential to human wellbeing. These structures reduce the force of waves before they reach shore, providing communities with vital protection from extreme weather such as hurricanes and cyclones. It is estimated that reefs safeguard hundreds of millions of people in more than 100 countries.

What is coral bleaching?

A key component of coral reefs are coral polyps—tiny soft bodied animals related to jellyfish and anemones. What we think of as coral reefs are actually colonies of hundreds to thousands of individual polyps. In hard corals, these tiny animals produce a rigid skeleton made of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). The calcium carbonate provides a hard outer structure that protects the soft parts of the coral. These hard corals are the primary building blocks of coral reefs, unlike their soft coral relatives that don’t secrete any calcium carbonate.

Coral reefs get their bright colors from tiny algae called zooxanthellae. The coral polyps themselves are transparent, and they depend on zooxanthellae for food. In return, the coral polyp provides the zooxanethellae with shelter and protection, a symbiotic relationship that keeps the greater reefs healthy and thriving.

When corals experience stress, like pollution and ocean warming, they can expel their zooxanthellae. Without the zooxanthellae, corals lose their color and turn white, a process known as coral bleaching. If bleaching continues for too long, the coral reef can starve and die.

Ocean warming and coral bleaching

Human-driven stressors, especially ocean warming, threaten the long-term survival of coral reefs. An alarming 77% of the world’s reef areas are already affected by bleaching-level heat stress.

The Great Barrier Reef is a stark example of the catastrophic impacts of coral bleaching. The Great Barrier Reef is made up of 3,000 reefs and is home to thousands of species of marine life. In 2025, the Great Barrier Reef experienced its sixth mass bleaching since 2016. It should also be noted that coral bleaching events are a new thing because of ocean warming, with the first documented in 1998.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

How you can help

The planet is changing rapidly, and the stakes have never been higher. The ocean has absorbed roughly 90% of the excess heat caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, and the consequences, including coral die-offs, are already visible. With just 2℃ of planetary warming, global coral reef losses are estimated to be up to 99% — and without significant change, the world is on track for 2.8°C of warming by century’s end.

To stop coral bleaching, we need to address the climate crisis head on. A recent study from Scripps Institution of Oceanography was the first of its kind to include damage to ocean ecosystems into the economic cost of climate change – resulting in nearly a doubling in the social cost of carbon. This is the first time the ocean was considered in terms of economic harm caused by greenhouse gas emissions, despite the widespread degradation to ocean ecosystems like coral reefs and the millions of people impacted globally.

This is why Ocean Conservancy advocates for phasing out harmful offshore oil and gas and transitioning to clean ocean energy. In this endeavor, Ocean Conservancy also leads international efforts to eliminate emissions from the global shipping industry—responsible for roughly 1 billion tons of carbon dioxide every year.

But we cannot do this work without your help. We need leaders at every level to recognize that the ocean must be part of the solution to the climate crisis. Reach out to your elected officials and demand ocean-climate action now.

The post What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs? appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs?

Ocean Acidification

What is a Snipe Eel?

From the chilly corners of the polar seas to the warm waters of the tropics, our ocean is bursting with spectacular creatures. This abundance of biodiversity can be seen throughout every depth of the sea: Wildlife at every ocean zone have developed adaptations to thrive in their unique environments, and in the deep sea, these adaptations are truly fascinating.

Enter: the snipe eel.

What Does a Snipe Eel Look Like?

These deep-sea eels have a unique appearance. Snipe eels have long, slim bodies like other eels, but boast the distinction of having 700 vertebrae—the most of any animal on Earth. While this is quite a stunning feature, their heads set them apart in even more dramatic fashion. Their elongated, beak-like snouts earned them their namesake, strongly resembling that of a snipe (a type of wading shorebird). For similar reasons, these eels are also sometimes called deep-sea ducks or thread fish.

How Many Species of Snipe Eel are There?

There are nine documented species of snipe eels currently known to science, with the slender snipe eel (Nemichthys scolopaceus) being the most studied. They are most commonly found 1,000 to 2,000 feet beneath the surface in tropical to temperate areas around the world, but sightings of the species have been documented at depths exceeding 14,000 feet (that’s more than two miles underwater)!

How Do Snipe Eels Hunt and Eat?

A snipe eel’s anatomy enables them to be highly efficient predators. While their exact feeding mechanisms aren’t fully understood, it’s thought that they wiggle through the water while slinging their beak-like heads back and forth with their mouths wide open, catching prey from within the water column (usually small invertebrates like shrimp) on their hook-shaped teeth.

How Can Snipe Eels Thrive So Well in Dark Depths of the Sea?

Snipe eels’ jaws aren’t the only adaptation that allows them to thrive in the deep, either. They also have notably large eyes designed to help them see nearby prey or escape potential predators as efficiently as possible. Their bodies are also pigmented a dark grey to brown color, a coloring that helps them stay stealthy and blend into dark, dim waters. Juveniles are even harder to spot than adults; like other eel species, young snipe eels begin their lives as see-through and flat, keeping them more easily hidden from predators as they mature.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

How Much Do Scientists Really Know About Snipe Eels?

Residence in the deep sea makes for a fascinating appearance, but it also makes studying animals like snipe eels challenging. Scientists are still learning much about the biology of these eels, including specifics about their breeding behaviors. While we know snipe eels are broadcast spawners (females release eggs into the water columns at the same time as males release sperm) and they are thought to only spawn once, researchers are still working to understand if they spawn in groups or pairs. Beyond reproduction, there’s much that science has yet to learn about these eels.

Are Snipe Eels Endangered?

While the slender snipe eel is currently classified as “Least Concern” on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species, what isn’t currently known is whether worldwide populations are growing or decreasing. And in order to know how to best protect these peculiar yet equally precious creatures, it’s essential we continue to study them while simultaneously working to protect the deep-sea ecosystems they depend on.

How Can We Help Protect Deep-Sea Species Like Snipe Eels?

One thing we can do to protect the deep sea and the wildlife that thrive within it is to advocate against deep-sea mining and the dangers that accompany it. This type of mining extracts mineral deposits from the ocean floor and has the potential to result in disastrous environmental consequences. Take action with Ocean Conservancy today and urge your congressional representative to act to stop deep-sea mining—animals like snipe eels and all the amazing creatures of the deep are counting on us to act before it’s too late.

The post What is a Snipe Eel? appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

Ocean Acidification

5 Animals That Need Sea Ice to Thrive

Today, we’re getting in the winter spirit by spotlighting five remarkable marine animals that depend on cold and icy environments to thrive.

1. Narwhals

Narwhals are often called the “unicorns of the sea” because of their long, spiraled tusk. Here are a few more fascinating facts about them:

- Believe it or not, their tusk is actually a tooth used for sensing their environment and sometimes for sparring.

- Narwhals are whales. While many whale species migrate south in the winter, narwhals spend their entire lives in the frigid waters of the circumpolar Arctic near Canada, Greenland and Russia.

- Sea ice provides narwhals with protection as they travel through unfamiliar waters.

2. Walruses

Walruses are another beloved Arctic species with remarkable adaptations for surviving the cold:

- Walruses stay warm with a thick layer of blubber that insulates their bodies from icy air and water.

- Walruses can slow their heart rate to conserve energy and withstand freezing temperatures both in and out of the water.

- Walruses use sea ice to rest between foraging dives. It also provides a vital and safe platform for mothers to nurse and care for their young.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

3. Polar Bears

Polar bears possess several unique traits that help them thrive in the icy Arctic:

- Although polar bear fur appears white, each hair is hollow and transparent, reflecting light much like ice.

- Beneath their thick coats, polar bears have black skin that absorbs heat from the sun. This helps keep polar bears warm in their icy habitat.

- Polar bears rely on sea ice platforms to access their primary prey, seals, which they hunt at breathing holes in the ice.

4. Penguins

Penguins are highly adapted swimmers that thrive in icy waters, but they are not Arctic animals:

- Penguins live exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere, mainly Antarctica, meaning they do not share the frigid northern waters with narwhals, walruses and polar bears.

- Penguins spend up to 75% of their lives in the water and are built for efficient aquatic movement.

- Sea ice provides a stable platform for nesting and incubation, particularly for species like the Emperor penguin, which relies on sea ice remaining intact until chicks are old enough to fledge.

5. Seals

Seals are a diverse group of carnivorous marine mammals found in both polar regions:

- There are 33 seal species worldwide, with some living in the Arctic and others in the Antarctic.

- There are two groups of seals: Phocidae (true seals) and Otariidae (sea lions and fur seals). The easiest way to tell seals and sea lions apart is by their ears: true seals have ear holes with no external flaps, while sea lions and fur seals have small external ear flaps.

- Seals need sea ice for critical life functions including pupping, nursing and resting. They also use ice for molting—a process in which they shed their fur in the late spring or early summer.

Defend the Central Arctic Ocean Action

Some of these cold-loving animals call the North Pole home, while others thrive in the polar south. No matter where they live, these marine marvels rely on sea ice for food, safety, movement and survival.

Unfortunately, a rapidly changing climate is putting critical polar ecosystems, like the Central Arctic Ocean, at risk. That is why Ocean Conservancy is fighting to protect the Central Arctic Ocean from threats like carbon shipping emissions, deep-sea mining and more. Take action now to help us defend the Central Arctic Ocean.

Learn more

Did you enjoy these fun facts? Sign up for our mobile list to receive trivia, opportunities to take action for our ocean and more!

The post 5 Animals That Need Sea Ice to Thrive appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility