Denmark is on its way to introducing a world-first tax on greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture in 2030.

Central to the proposals – announced by the Danish government on 24 June – is the plan to charge farmers for emissions from their livestock.

This carbon tax would cost around €100 (£85) annually per cow, according to the Financial Times.

The proposal is one part of a wider agreement between the government and different agriculture and environmental groups aimed at helping the country meet its climate goals for 2030 and beyond.

As a major producer of dairy and pork, one-quarter of Denmark’s greenhouse gas emissions come from agriculture.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief explains the agriculture tax plans, the possible impacts on farmers and the effect it could have on cutting Denmark’s emissions.

- How will the tax work?

- How will this tax help Denmark meet its climate targets?

- How was the agreement reached?

- What will the tax mean for Danish farmers?

- Are other countries planning to introduce a carbon tax on agriculture?

How will the tax work?

Under the proposed plans, Danish landowners will pay a levy based on their emissions from “livestock, fertiliser, forestry and the disturbance of carbon-rich agricultural soils”, the Copenhagen Post reported.

The effective cost of the tax paid by farmers will amount to 120 Danish kroner (£14/$18) per tonne of CO2-equivalent (CO2e) emitted when the tax is implemented in 2030. It will rise to 300 kroner (£34/$44) per tonne of CO2e from 2035 onwards.

The true cost of these taxes is actually higher (300 kroner per tonne of CO2e in 2030 and 750 kroner per tonne from 2035 onwards), but the government will also implement a 60% deduction. The aim of this “basic tax break” is to “limit the impact of the measure on production costs”, says EurActiv. It adds that, in the long run, “the most climate-efficient farms could be close to paying no tax”.

The proceeds of the levy “are to be pooled in a fund to support the livestock industry’s green transition for at least two years after the tax comes into effect”, according to the Guardian.

The tax is just one element of a wider agreement on a “Green Denmark”. This was signed by a “green tripartite”, namely, a three-party agreement between the Danish government, conservation groups and the Danish industrial and agricultural sectors.

The agreement aims to “form the long-term basis for a historic reorganisation and transformation of Denmark’s land and of food and agricultural production”.

Under the deal, Denmark will relinquish some agricultural lands to provide more space for nature and biodiversity. Those lands will comprise heaths, meadows, river valleys and bogs that had historically been converted to agriculture.

The country will plant 250,000 hectares of new forests by 2045 and set aside 140,000 hectares of lowlands to protect their carbon-rich soils by 2030. It will also acquire strategic agricultural lands and distribute or sell them to private and public investments to “contribute to large nature areas” or “installation of renewable energy” and boost technologies and measures to cut emissions, the agreement says.

All these targets will be financed by a new Denmark’s Green Area Fund, which amounts to 40bn kroner (£4.6bn/$5.9bn). Denmark’s government will also use EU agricultural subsidies for the technology transition.

Finally, the agreement also aims to improve Denmark’s coastal waters and freshwater and reduce nitrogen fertiliser use.

The Danish parliament still needs to approve the plan, but Reuters noted that “political experts expect a bill to pass following the broad-based consensus”.

How will this tax help Denmark meet its climate targets?

According to Denmark’s most recent national inventory report, the agricultural sector is the country’s second-largest source of emissions, after the energy sector.

Agriculture contributes around 28% of Denmark’s total greenhouse gas emissions, the report says, and accounts for more than 80% of methane and nitrous oxide emissions specifically.

A “major part” of these emissions stem from livestock production, the report says. Denmark has more than 15,000 livestock farms containing millions of cows, pigs and other animals.

The country’s high agriculture emissions “cannot continue”, the climate minister Lars Aagaard said in a statement about the CO2-cutting proposals, adding that a “great deal of work awaits” to implement these plans.

By 2030, the country is aiming to cut overall greenhouse gas emissions by 70% and agriculture and forestry emissions by 55-65%.

The new proposals are estimated to cut 1.8m tonnes of CO2e emissions in 2030, according to the government.

This will help Denmark meet its 2030 climate goals and “take a big step closer to becoming climate neutral in 2045”, tax minister Jeppe Bruus said in a statement.

The agreement will also boost forests, large wetlands and nature protection, according to the president of the Danish Society for Nature Conservation, Maria Reumert Gjerding.

Prof Søren Petersen, a soil microbiologist at Aarhus University in Denmark, agrees that the plan “could lead to substantial reductions in agricultural emissions” if implemented correctly. He tells Carbon Brief:

“It is my impression that there is a real interest in promoting climate-smart solutions and developing solutions that achieve real reductions in emissions.”

Petersen says that the agreement highlights the “need to speed up” new climate technologies and measures to cut greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. He adds:

“Perhaps the greatest barrier at the moment is that many technologies with potential for greenhouse gas mitigation have not yet been sufficiently documented, or that the source is highly variable and difficult to quantify.”

He notes that it is often “difficult to measure” agricultural emissions, adding:

“If we can arrive at a set of criteria for documenting emissions, and effects of mitigation measures, and if such criteria can also be accepted in the international review of the national inventory, then I do think there is potential for developing several technologies for use at farm level.

“But tangible impact will require land use changes, as well as mitigation technologies.”

Niklas Sjøbeck Jørgensen, senior advisor on food and bioresources at Green Transition Denmark, an environmental thinktank, says the agreement is “an important step in a greener direction”.

But, he says, it “fails by maintaining problematic animal production”, adding in a statement:

“Unfortunately, the CO2 tax is correspondingly lagging behind, as the floor deduction of 60% and large technology subsidies maintain the current intensive form of animal production.”

How was the agreement reached?

The Danish government and the other members of the green tripartite reached this “historic agreement” after almost five months of talks, Politico reported.

Agreeing the tax “has been a very difficult journey”, Martin Kristian Brauer, chief economist at the Danish Agriculture and Food Council, one of Denmark’s largest organisations representing farmers and part of the green tripartite, tells Carbon Brief.

Brauer says his organisation had been against the tax from the beginning of the negotiations since “the risk connected to such a tax is far too big for the sector”. But over the past two years, they have worked on identifying those risks, listening to farmers’ concerns and negotiating with the government. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Although we have many [farmers] in Denmark still oppos[ing] this tax, I think we reached a point where we can live with it.”

Brauer says that broad participation of the different sectors was fundamental to allowing this “very difficult issue” to turn “into real politics”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“That was an agreement among all the parties. It was not just closing a lot of agricultural farms and thereby reducing emissions. The goal was to make a new regulation, where Danish agriculture meets climate goals, but [also having] the possibility to develop…an economically sustainable sector.”

Members of the tripartite agreed that the country “must have a strong and competitive” agricultural sector “with attractive business potential and jobs”, according to a statement by the Danish Ministry of Economic Affairs.

The agreement also stated that the new Green Area Fund would attempt to “facilitate a land conversion that mitigates the economic consequences for Danish agriculture”.

Brauer points out that there will be subsidies to incentivise farmers to enrol in the programme. The Green Area Fund, according to the agreement, will support private afforestation, the conservation of aquatic ecosystems and drinking water and the conversion of other lands, including wetlands and lowlands.

What will the tax mean for Danish farmers?

Petersen tells Carbon Brief that the agricultural CO2 tax proposal is “quite flexible and lenient on farmers”.

He notes that the gradual increase in the cost farmers will pay from 2030 to 2035 will “buy time for farmers to adjust, and for researchers to deliver the documentation of the effects of potential mitigation measures”.

In fact, farmers that comply with proven climate solutions “can avoid the tax”, according to a statement by Søren Søndergaard, president of the Danish Agriculture and Food Council.

The agreement provides a number of climate measures already available for farms from fertiliser use to livestock feed management. It also states that Denmark’s government will document and look for new climate technologies and measures for the agricultural sector.

Feed additives may be used to reduce direct emissions from livestock, Brauer notes. He tells Carbon Brief:

“That is an additive put into the feed and when the cows eat [it], emissions are reduced by maybe 20 or 30%.”

Another part of the agreement is land conversion and management. The territorial reorganisation will be planned and implemented by local governments, with the participation of coastal water councils and river basin management groups, the agreement says.

Brauer, from the Danish Agriculture and Food Council, says that land conversion does not mean farmers will lose their lands, instead, they will receive a subsidy to “convert the land”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The farmer in Denmark in the future will be not just an agricultural farmer, he will actually be a land manager and will have some areas which [are] going to be traditional agricultural farming, forests and maybe wetlands. So he will have a portfolio of different kinds of lands in his state that will all generate some income.”

The agreement points out that farmers’ participation in setting aside carbon-rich shallow soils and reducing nitrogen emissions is voluntary, but they can obtain financial incentives from the new fund for doing so.

Brauer adds that for those goals, each Danish region is mandated to reach certain targets. He says:

“If that area does not meet these goals together, then there will be a mandatory regulation set up for each farmer, pushed from the government.”

Regarding how small producers would be impacted, the agreement mentions that it is being analysed how to determine when a producer or farm will be subject to taxation, through a threshold that aims “to exempt farms with relatively low greenhouse gas emissions to ensure that the total administrative and economic costs of the tax are commensurate with the potential CO2e reductions”.

Are other countries planning to introduce a carbon tax on agriculture?

Denmark is the first country to introduce this kind of legislation, although other countries have considered it and, until recently, New Zealand was pioneering similar moves.

Around half of New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions come from agriculture, primarily livestock. To tackle this, in 2022 the previous government planned to include agriculture in the country’s emissions trading scheme from 2025 onwards.

Under this scheme, the government sets a limit for the amount of greenhouse gases companies in certain sectors can emit. Companies whose emissions fall under the limit can sell their extra allowances to other organisations. These limits reduce over time, in line with climate targets.

Some New Zealand farmers protested these plans and the government received pushback from farm lobby groups.

In June this year, the country’s relatively new centre-right government scrapped plans for the so-called “burp tax” – a reference to the methane produced by livestock. This fulfilled a “pre-election pledge by [New Zealand prime minister] Christopher Luxon’s National Party”, Al Jazeera said at the time.

The government said it would instead invest hundreds of millions of dollars on emissions-reduction technology and boost funding for an agricultural greenhouse gas research centre.

Agriculture minister Todd McClay said that the government is “committed to meeting our climate change obligations without shutting down Kiwi farms”.

The Green and Labour parties criticised the government’s decision, Radio New Zealand reported.

In the EU, there have been on-and-off discussions about bringing agriculture into the bloc’s emissions trading system.

In March, Carbon Pulse reported that the EU was “testing the waters” on either creating a new emissions trading system for agriculture or revising existing rules.

Since then, a new European parliament was elected and the next European Commission line-up will be finalised this summer.

The EU’s climate advisory board earlier this year recommended introducing emissions pricing for agriculture and land use.

Danish prime minister, Mette Frederiksen, said she hopes Denmark’s planned agriculture carbon tax will “pave the way forward regionally and globally” for similar moves, the Financial Times reported.

Brauer says that farmers in Denmark are “quite concerned” about the tax as it may lead to Danish products being “a little bit more expensive than a product from Germany or from elsewhere”. He adds:

“If we get some kind of regulation in the whole EU, this difficulty would disappear.”

The post Q&A: How Denmark plans to tax agriculture emissions to meet climate goals appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: How Denmark plans to tax agriculture emissions to meet climate goals

Climate Change

Analysis: UK newspaper editorial opposition to climate action overtakes support for first time

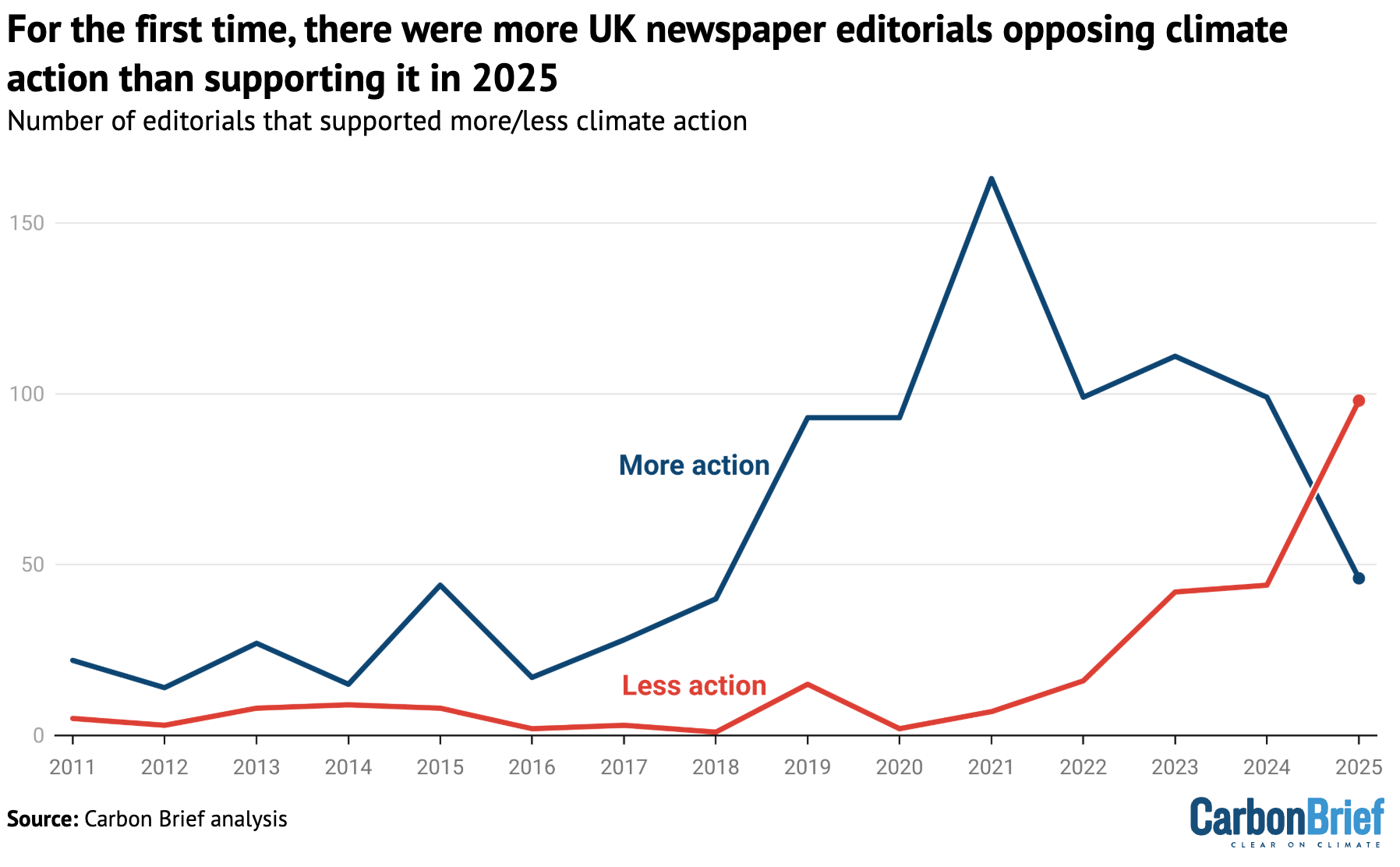

Nearly 100 UK newspaper editorials opposed climate action in 2025, a record figure that reveals the scale of the backlash against net-zero in the right-leaning press.

Carbon Brief has analysed editorials – articles considered the newspaper’s formal “voice” – since 2011 and this is the first year opposition to climate action has exceeded support.

Criticism of net-zero policies, including renewable-energy expansion, came entirely from right-leaning newspapers, particularly the Sun, the Daily Mail and the Daily Telegraph.

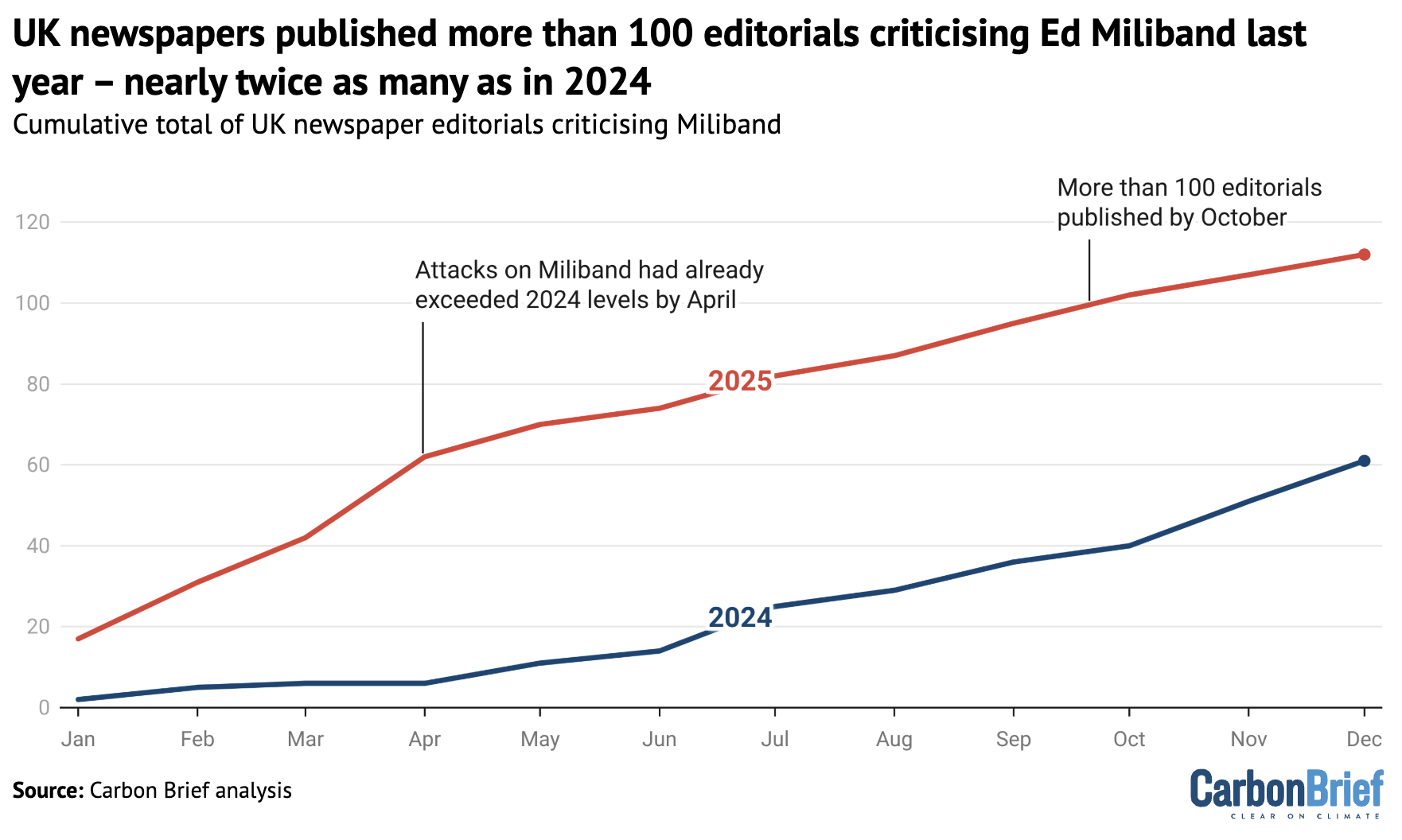

In addition, there were 112 editorials – more than two a week – that included attacks on Ed Miliband, continuing a highly personal campaign by some newspapers against the Labour energy secretary.

These editorials, nearly all of which were in right-leaning titles, typically characterised him as a “zealot”, driving through a “costly” net-zero “agenda”.

Taken together, the newspaper editorials mirror a significant shift on the UK political right in 2025, as the opposition Conservative party mimicked the hard-right populist Reform UK party by definitively rejecting the net-zero target that it had legislated for and the policies that it had previously championed.

Record climate opposition

Nearly 100 UK newspaper editorials voiced opposition to climate action in 2025 – more than double the number of editorials that backed climate action.

As the chart below shows, 2025 marked the fourth record-breaking year in a row for criticism of climate action in newspaper editorials.

This also marks the first time that editorials opposing climate action have overtaken those supporting it, during the 15 years that Carbon Brief has analysed.

This trend demonstrates the rapid shift away from a long-standing political consensus on climate change by those on the UK’s political right.

Over the past year, the Conservative party has rejected both the “net-zero by 2050” target that it legislated for in 2019 and the underpinning Climate Change Act that it had a major role in creating. Meanwhile, the Reform UK party has been rising in the polls, while pledging to “ditch net-zero”.

These views are reinforced and reflected in the pages of the UK’s right-leaning newspapers, which tend to support these parties and influence their politics.

All of the 98 editorials opposing climate action were in right-leaning titles, including the Sun, the Daily Mail, the Daily Telegraph, the Times and the Daily Express.

Conversely, nearly all of the 46 editorials pushing for more climate action were in the left-leaning and centrist publications the Guardian and the Financial Times. These newspapers have far lower circulations than some of the right-leaning titles.

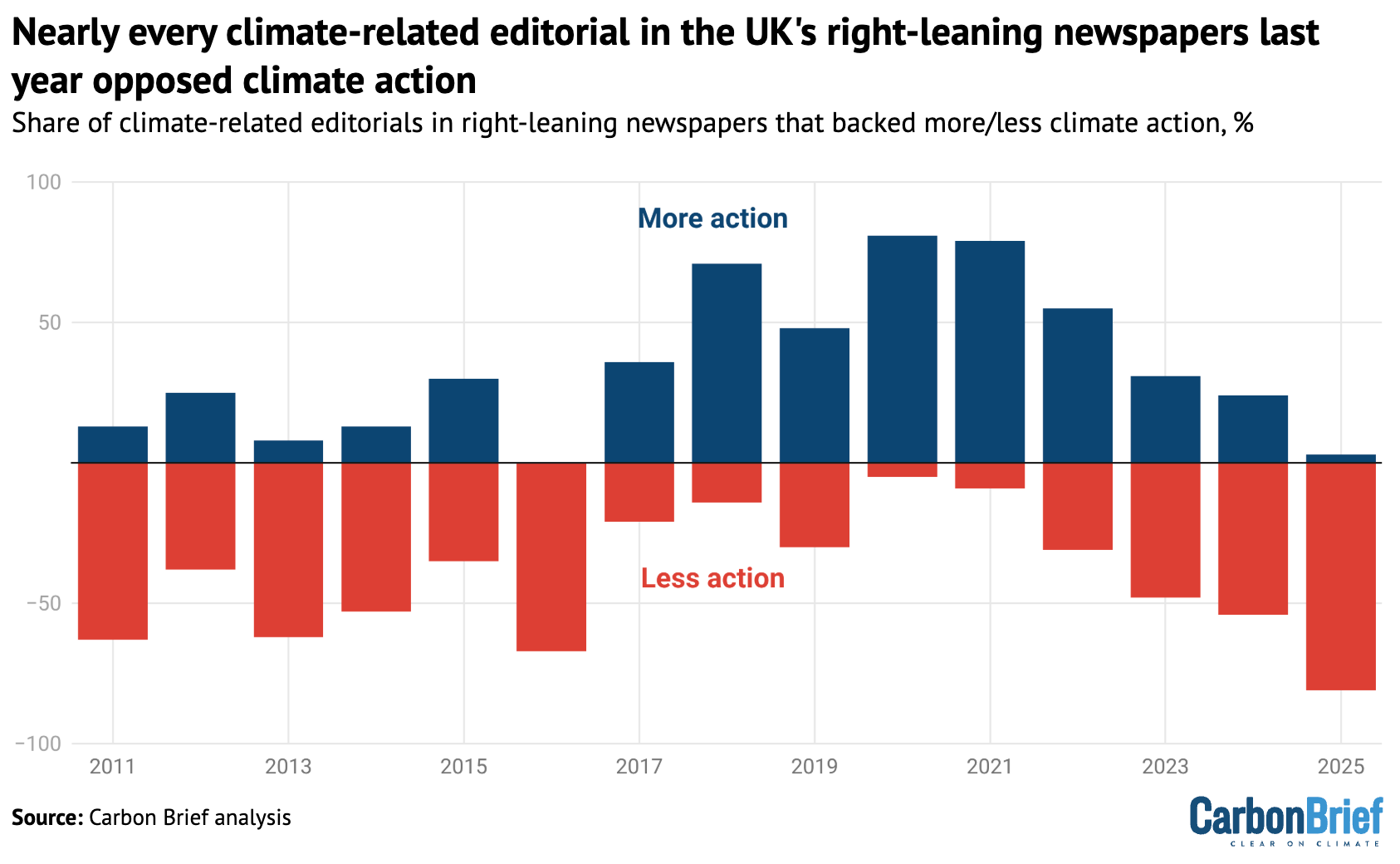

In total, 81% of the climate-related editorials published by right-leaning newspapers in 2025 rejected climate action. As the chart below shows, this is a marked difference from just a few years ago, when the same newspapers showed a surge in enthusiasm for climate action.

That trend had coincided with Conservative governments led by Theresa May and Boris Johnson, which introduced the net-zero goal and were broadly supportive of climate policies.

Notably, none of the editorials opposing climate action in 2025 took a climate-sceptic position by questioning the existence of climate change or the science behind it. Instead, they voiced “response scepticism”, meaning they criticised policies that seek to address climate change.

(The current Conservative leader, Kemi Badenoch, has described herself as “a net-zero sceptic, not a climate change sceptic”. This is illogical as reaching net-zero is, according to scientists, the only way to stop climate change from getting worse.)

In particular, newspapers took aim at “net-zero” as a catch-all term for policies that they deemed harmful. Most editorials that rejected climate action did not even mention the word “climate”, often using “net-zero” instead.

This supports recent analysis by Dr James Painter, a research associate at the University of Oxford, which concluded that UK newspaper coverage has been “decoupling net-zero from climate change”.

This is significant, given strong and broad UK public support for many of the individual climate policies that underpin net-zero. Notably, there is also majority support for the “net-zero by 2050” target itself.

Much of the negative framing by politicians and media outlets paints “net-zero” as something that is too expensive for people in the UK.

In total, 87% of the editorials that opposed climate action cited economic factors as a reason, making this by far the most common justification. Net-zero goals were described as “ruinous” and “costly”, as well as being blamed – falsely – for “driving up energy costs”.

The Sunday Telegraph summarised the view of many politicians and commentators on the right by stating simply that said “net-zero should be scrapped”.

While some criticism of net-zero policies is made in good faith, the notion that climate change can be stopped without reducing emissions to net-zero is incorrect. Alternative policies for tackling climate change are rarely presented by critical editorials.

Moreover, numerous assessments have concluded that the transition to net-zero can be both “affordable” and far cheaper than previously thought.

This transition can also provide significant economic benefits, even before considering the evidence that the cost of unmitigated warming will significantly outweigh the cost of action.

Miliband attacks intensify

Meanwhile, UK newspapers published 112 editorials over the course of 2025 taking personal aim at energy security and net-zero secretary Ed Miliband.

Nearly all of these articles were in right-leaning newspapers, with the Sun alone publishing 51. The Daily Mail, the Daily Telegraph and the Times published most of the remainder.

This trend of relentlessly criticising Miliband personally began last year in the run up to Labour’s election victory. However, it ramped up significantly in 2025, as the chart below shows.

Around 58% of the editorials that opposed climate action used criticism of climate advocates as a justification – and nearly all of these articles mentioned Miliband, specifically.

Editorials denounced Miliband as a “loon” and a “zealot”, suffering from “eco insanity” and “quasi-religious delusions”. Nicknames given to him include “His Greenness”, the “high priest of net-zero” and “air miles Miliband”.

Many of these attacks were highly personal. The Daily Mail, for example, called Miliband “pompous and patronising”, with an “air of moral and intellectual superiority”.

Frequently, newspapers refer to “Ed Miliband’s net-zero agenda”, “Ed Miliband’s swivel-eyed targets” and “Mr Miliband’s green taxes”.

These formulations frame climate policies as harmful measures that are being imposed on people by the energy secretary.

In fact, the Labour government decisively won an election in 2024 with a manifesto that prioritised net-zero policies. Often, the “targets” and “taxes” in question are long-standing policies that were introduced by the previous Conservative government, with cross-party support.

Moreover, the government’s climate policy not only continues to rely on many of the same tools created by previous administrations, it is also very much in line with expert evidence and advice. This is to prioritise the expansion of clean power and to fuel an economy that relies on increasing levels of electrification, including through electric cars and heat pumps.

Despite newspaper editorials regularly calling for Miliband to be “sacked”, prime minister Keir Starmer has voiced his support both for the energy secretary and the government’s prioritisation of net-zero.

In an interview with podcast The Rest is Politics last year, Miliband was asked about the previous Carbon Brief analysis that showed the criticism aimed at him by right-leaning newspapers.

Podcast host Alastair Campbell asked if Miliband thought the attacks were the legacy of his strong stance, while Labour leader, during the Leveson inquiry into the practices of the UK press. Miliband replied:

“Some of these institutions don’t like net-zero and some of them don’t like me – and maybe quite a lot of them don’t like either.”

Renewable backlash

As well as editorial attitudes to climate action in general, Carbon Brief analysed newspapers’ views on three energy technologies – renewables, nuclear power and fracking.

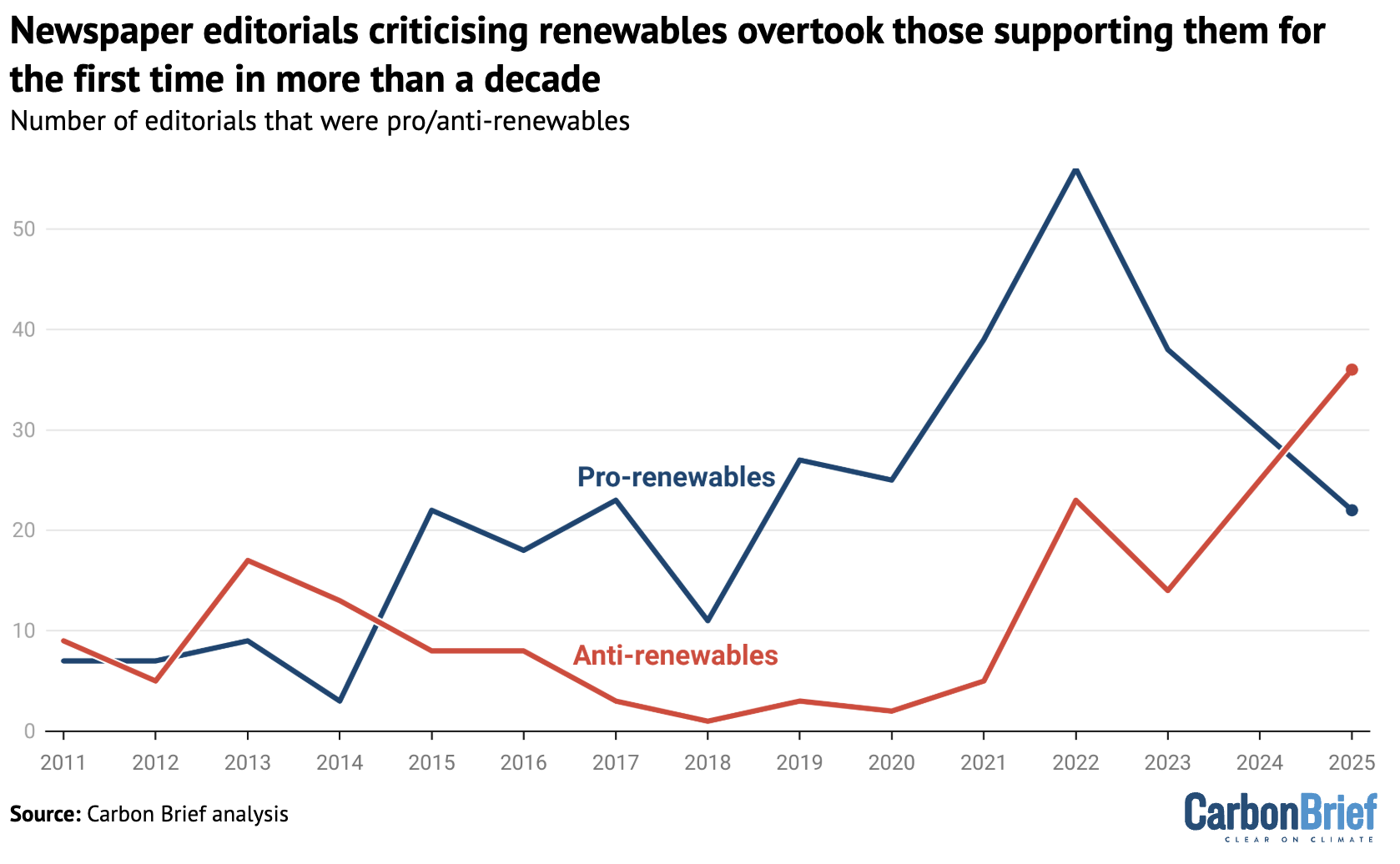

There were 42 newspaper editorials criticising renewable energy in 2025. This meant that, for the first time since 2014, there were more anti-renewables editorials than pro-renewables editorials, as the chart below shows.

As with climate action more broadly, this was a highly partisan issue. The Times was the only right-leaning newspaper that published any editorials supporting renewables.

By far the most common stated reason for opposing renewable energy was that it is “expensive”, with 86% of critical editorials using economic arguments as a justification.

The Sun referred to “chucking billions at unreliable renewables” while the Daily Telegraph warned of an “expensive and intermittent renewables grid”.

At the same time, editorials in supportive publications also used economic arguments in favour of renewables. The Guardian, for example, stressed the importance of building an “affordable clean-energy system” that is “built on renewables”.

There was continued support in right-leaning publications for nuclear power, despite the high costs associated with the technology. In total, there were 20 editorials supporting nuclear power in 2025 – nearly all in right-leaning newspapers – and none that opposed it.

Fracking was barely mentioned by newspapers in 2023 and 2024, after a failed push by the Conservatives under prime minister Liz Truss to overturn a ban on the practice in 2022. This attempt had been accompanied by a surge in supportive right-leaning newspaper editorials.

There was a small uptick of 15 editorials supporting fracking in 2025, as right-leaning newspapers once again argued that it would be economically beneficial.

The Sun urged current Conservative leader Badenoch to make room for this “cheap, safe solution” in her future energy policy. The government plans to ban fracking “permanently”.

North Sea oil and gas remained the main fossil-fuel policy focus, with 30 editorials – all in right-leaning newspapers – that mentioned the topic. Most of the editorials arguing for more extraction from the North Sea also argued for less climate action or opposed renewable energy.

None of these editorials noted that the UK is expected to be significantly less reliant on fossil-fuel imports if it pursues net-zero, than if it rolls back on climate action and attempts to squeeze more out of the remaining deposits in the North Sea.

Methodology

This is a 2025 update of previous analysis conducted for the period 2011-2021 by Carbon Brief in association with Dr Sylvia Hayes, a research fellow at the University of Exeter. Previous updates were published in 2022, 2023 and 2024.

The count of editorials criticising Ed Miliband was not conducted in the original analysis.

The full methodology can be found in the original article, including the coding schema used to assess the language and themes used in editorials concerning climate change and energy technologies.

The analysis is based on Carbon Brief’s editorial database, which is regularly updated with leading articles from the UK’s major newspapers.

The post Analysis: UK newspaper editorial opposition to climate action overtakes support for first time appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: UK newspaper editorial opposition to climate action overtakes support for first time

Climate Change

Power play: Can a defensive Europe stick with decarbonisation in Davos?

Tsvetelina Kuzmanova is EU sustainable finance lead for the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), based in Brussels.

Europe is set to arrive in Davos on the defensive after a year of trade uncertainty and tariff threats from the Trump administration, as well as pressure to roll back core elements of the EU’s Green Deal. The war in Ukraine and situation in Greenland also continue to test Europe’s security and strategic cohesion.

While Trump’s administration is “coming in force” to the World Economic Forum in the Swiss ski resort of Davos with the largest-ever US delegation, Europe is not showing up in a strong position or as a shaper of the global agenda. Instead, it has become reactive to other global powers.

Amid the pressure, it is crucial that the EU maintains its ambitions on energy security and decarbonisation, both against headwinds at Davos and by continuing to uphold the energy transition. This is not about climate leadership alone, but a question of power and independence. Maintaining the energy transition is central to reducing geopolitical exposure, limiting external leverage and preserving Europe’s ability to act strategically, including in negotiations on the next EU budget.

Over the past year, debates in Europe have increasingly framed climate ambition as a liability to competitiveness. Green policies have been softened, delayed or revised in the name of industrial survival.

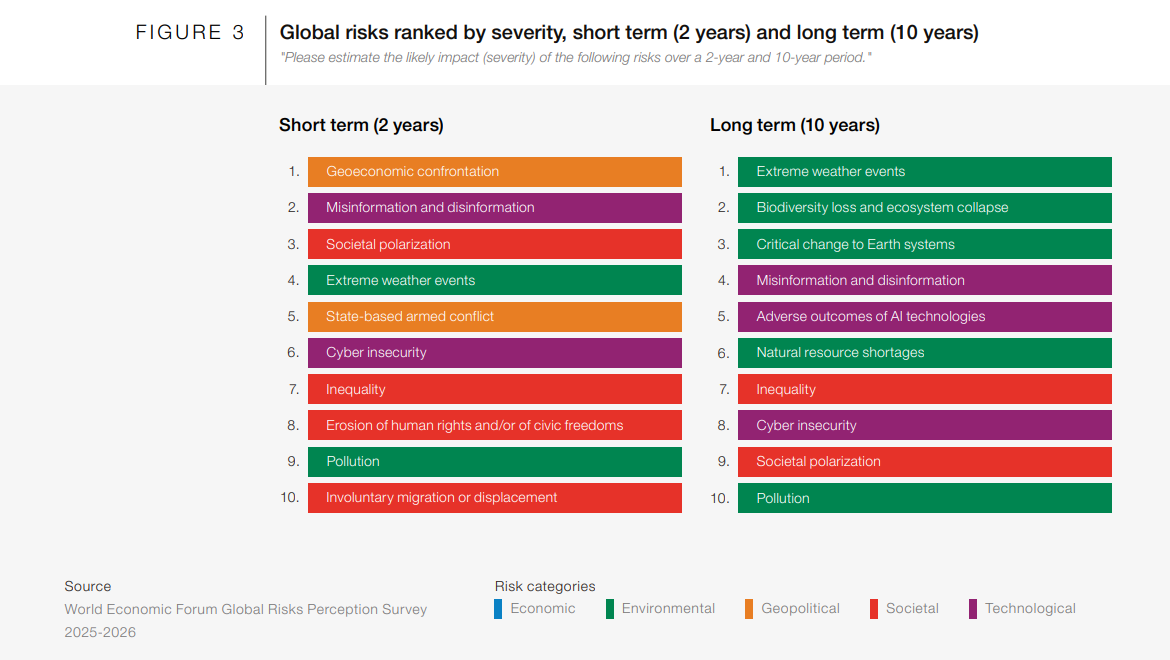

Yet global leaders identify climate-driven disruption as the most likely defining risk of the 2030s. Looking a decade into the future, climate collapse and extreme weather dominate the risk landscape, according to the World Economic Forum’s newly published Global Risks Report 2026 . Economic downturn, by contrast, sits far lower on the list at 24.

Near-term risks for Europe

Even setting aside the risk of climate change, Europe’s vulnerabilities are painfully concrete in the short-term: energy remains a pressure point, trade is increasingly weaponised, supply chains are exposed, and geopolitical leverage continues to be exercised through fossil fuel supplies.

If recent history taught Europe anything, it should have been that such dependency directly threatens economic prosperity, as was seen during the 2022 energy crisis.

Oil and gas remain central to geopolitical arm-twisting, including supply threats, price manipulation or diplomatic pressure – for example, the US and Qatar telling the European Union that its corporate sustainability due diligence directive threatens LNG supplies to the bloc.

Strategic spending or strategic drift

In this context, the EU budget is a geopolitical choice as much as a fiscal exercise. It will run until 2034, meaning it overlaps almost exactly with when long-term risks will become tomorrow’s reality and frame Europe’s place on the global stage for almost a decade.

Choices will have to be made as public money is scarce and there is no chance of further joint European debt. The question is whether Europe uses its limited fiscal firepower to preserve the status quo or to address its vulnerabilities and the long-term economic risks.

This is where electrification, grids, incentivising cleantech and greening Europe’s heavy industry come in. These shouldn’t be viewed just as climate projects, but as instruments of strategic autonomy.

Governments defend clean energy transition as US snubs renewables agency

Other economies are already doing this. China will spend 4 trillion yuan ($574 billion) by 2030 in electricity grid infrastructure, treating transmission and system balancing as core national assets.

Even under the Trump administration, the US has continued to scale up grid investment. Last year, it recorded the highest level of grid spending globally, at around $115 billion, accounting for roughly a quarter of total worldwide investment. A significant share of this has been driven by federal funding for grid modernisation and transmission expansion, explicitly linking energy infrastructure to industrial competitiveness and security.

Meanwhile, Europe estimates that it needs close to €600 billion in grid investment by 2030, yet annual spending remains fragmented across national systems and constrained by permitting and financing bottlenecks. This comparison underscores why the next Multiannual Financial Framework (the EU budget) must prioritise strategic public spending on grids, electrification and related infrastructure.

Bolstering competitiveness with electricity

Despite the narrative being pushed by the US in forums like Davos, industrial electrification, system flexibility and cleantech scale-up are prerequisites for a competitive industry in a decarbonising world.

Electrification is critical to reducing vulnerability to fossil fuel imports and grids are essential to do this at scale. This shift would also reduce Europe’s exposure to the very risks flagged by the World Economic Forum, from climate-driven instability to energy and supply-chain shocks, turning vulnerability into strategic resilience.

This is a textbook case for mission-oriented public investment – not picking individual corporate winners but backing system-level capabilities that markets will not support enough despite their strategic importance.

Q&A: “False” climate solutions help keep fossil fuel firms in business

In today’s global economy, power flows from control over infrastructure, energy systems and industrial capacity. Without the underlying investment, even the most sophisticated regulatory frameworks risk becoming aspirational.

And, if Europe does not decisively shift towards investing in electrification, grids and industrial transformation, it will remain exposed to pressure tactics, with oil and gas supplies shaping Europe’s future and making it reactive rather than proactive at meetings like Davos.

Any talk of resilience, competitiveness and strategic autonomy at Davos will be hollow if Europe is unable to match it with spending decisions that address future risks and drive ahead with decarbonisation.

The post Power play: Can a defensive Europe stick with decarbonisation in Davos? appeared first on Climate Home News.

Power play: Can a defensive Europe stick with decarbonisation in Davos?

Climate Change

An Alabama Mayor Signed an NDA With a Data Center Developer. Read It Here.

The non-disclosure agreement was a major sticking point in a lively town hall that featured city officials, data center representatives and more than a hundred frustrated residents.

COLUMBIANA, Ala.—At first, no one knew about the non-disclosure agreement.

An Alabama Mayor Signed an NDA With a Data Center Developer. Read It Here.

-

Greenhouse Gases5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits