中国的气候和能源政策呈现出一种悖论:在以惊人的速度发展清洁能源的同时,也未停下新建燃煤电厂的步伐。

仅在2023年,中国就新建了70吉瓦(GW)的煤电装机容量,比2019年增长了四倍,占当年全球新增煤电装机容量的95%。

煤电产能的激增引发了人们对中国二氧化碳(CO2)排放和气候目标能否实现,以及对未来出现搁浅资产风险的担忧。

由于光伏和风能发电量不稳定,中国政府将煤炭作为保障能源安全和满足快速增长的用电高峰的手段。

与此同时,中国的电力行业在成本、需求模式、监管和市场运作方面正在发生重大变化。我们的新研究表明,用于证明新煤炭产能合理性的传统经济计算方式可能已经过时。

我们使用一个简单的分析指标来评估能满足用电高峰需求的最经济方式是什么。结果表明,光伏加电池储能的组合可能是比新建煤电更具成本效益的选择。

中国电力格局发生了怎样的变化?

在过去十年里,可再生能源和电池储能的成本大幅下降,高峰时段的住宅和商业用电需求激增,电力交易市场获得了更大的吸引力。

与此同时,中国还宣布了“双碳”目标,即在2030年前实现碳达峰、2060年前实现碳中和。鉴于这些转型,建设更多未减排的煤电厂与中国的长期气候承诺相冲突,而且对满足用电需求对增长来说,可能不再是最具成本效益的选择。它还占用了清洁能源系统转型急需的资金。

替代指标如何评估成本?

我们的研究引入了一种替代指标,用于计算在满足不断增长的高峰用电需求的情况下,所需的最优成本投资。

这一指标,即“净容量成本”(net capacity cost),是满足用电高峰需求所需的基础设施投资的年化固定成本,减去该设施带给电力市场的收入,或其“系统价值”(system value)。 在该指标中,负数意味着这些投资将带来利润,而非支出。

为了探索在中国使用的情境,我们使用了一个简单的例子:在一个假定省份,高峰用电需求增加了1500兆瓦(MW)、全年需求增加了6570吉瓦时(GWh)。

然后,我们概述了满足高峰和全年能源需求的五种策略(情况),其涵盖了从严重依赖煤电到光伏和电池储能相结合的方式。

在不同的案例中,资源衡量的规模基于它们能够可靠地满足高峰供应需求和年度能源需求的程度。

- 情况1:新的煤炭发电能力可满足高峰和年度能源需求的所有增长。

- 情况2:光伏可满足70%的年度能源需求增长,煤炭可满足30%的年度能源需求增长;光伏可满足525兆瓦的高峰供应需求(由于光伏发电可能不在高峰期间,因此基于“容量可信度”进行折减),而煤电可提供剩余的975兆瓦。

- 情况3:光伏可满足所有年度能源需求增长;光伏和煤炭均可满足750兆瓦的高峰供应需求,同样通过容量可信度对光伏发电量进行折减。

- 情况4:光伏满足所有年度能源需求增长;光伏和电池均为高峰供电需求提供750兆瓦;电池提供调频储备(用于管理精确至分钟的供需差异的备用电源)。

- 情况5:光伏满足所有年度能源需求增长;广泛和电池均为高峰供电需求提供750兆瓦;电池提供能源套利(在价格或成本较低时充电,在价格或成本较高时放电)。

如下图所示,我们针对每种情况都计算了单个资源(煤、电池或光伏),以及整个系统每年获得1千瓦(kW)发电容量的年净成本,单位为人民币元。

表上半部分的资源净容量成本是指该资源的净成本(即年化固定成本减去该资源从提供能源和辅助服务,如调频,所获得的年收入)。正数表示电网运营商在增加或获取该资源时的净成本。

表下半部分的系统总净容量成本,是在每种情况下利用资源组合满足高峰需求增长的净成本。

我们用于计算系统净成本的权重是基于装机容量与高峰需求增长的比率。

不同能源组合满足用电需求的成本

| 情况 1 | 情况 2 | 情况 3 | 情况 4 | 情况 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 资源净容量成本 (元/千瓦/年, 每千瓦装机容量) | |||||

| 煤炭 | 424 | 424 | 512 | ||

| 电池 | 248 | 781 | |||

| 光伏 | -128 | -128 | -128 | -128 | |

| 系统净容量成本 (元/千瓦/年, 每千瓦满足高峰用电需求且折减容量可信度后) | |||||

| 煤炭 | 471 | 306 | 236 | ||

| 电池 | 138 | 434 | |||

| 光伏 | -223 | -319 | -319 | -319 | |

| 总计 | 471 | 83 | -83 | -181 | 115 |

为了对这一简单分析进行压力测试,我们研究了不同来源的各种价格的敏感性。

由于中国的光伏价格已经很低,我们的敏感性分析主要集中在煤炭、电池和其他分析所需投入的价格上。

满足高峰用电需求最经济的方法是什么?

我们的结果表明,当电池储能提供调频储备时(情况4),光伏和储能的组合是满足高峰用电需求增长最具成本效益的选择。

在这种组合下,每获得1千瓦发电装机容量,电网运营商的成本为-181元(约-25美元或-20英镑)。

相比之下,新建煤电产能以满足高峰用电需求增长(情况1)是最昂贵的方案,每获得1千瓦装机容量的净容量成本为471元(约合65美元或52英镑)。

情况3,即大型煤电厂仅用作备用电源(几乎不发电),在中国可能出于政治原因而至少在短期内不可行。

另外两种情况(情况2和情况5)更具可比性,但鉴于自本分析报告发布以来,电池价格下降了30%以上,约为每瓦时(Wh)1元人民币(约合0.14美元或0.11英镑),因此情况5中的电池可能比情况2中的煤炭更具经济吸引力。

我们的解决方案如何助力中国实现气候目标?

我们的分析表明,为了应对不断变化的形势,在满足中国日益增长的能源需求的同时,实现其气候目标的近期战略是将电池储能纳入电力市场。

目前,中国政府允许包括电池在内的“新型储能”参与电力市场。然而,详细规定尚不明确,电池的参与可以更简单。

例如,电池储能不被允许提供“运转储备”,即为应对意外的供需误差所预留的发电量。如果允许电池储能提供运转储备,将增强其商业价值。

允许电池储能更多地参与市场将促进电池储能系统的持续创新和降低成本,同时为系统运营商提供宝贵的运营经验。

这种策略将与市场效益相符,并反映美国和欧洲近期的电力市场经验。

这也将有助于解决近期的产能和能源需求,因为电池和光伏发电通常比燃煤电厂的建设速度更快。

此外,它还有助于缓解未来新增燃煤发电与可再生能源之间的冲突。主要作为可再生能源发电备用电源的新建燃煤电厂要么很少运营,要么侵占了其他现有煤炭发电厂的运营时间和净收入,从而产生新搁浅资产的风险。

通过继续进行电力市场改革,也将促进对可再生能源发电和电力储存进行更有效的投资。

允许市场制定批发市场电价、允许可再生能源发电和电力储存参与批发市场,这可以提高其收入和利润。

此外,改革还将鼓励高效利用储能,这是我们的关键发现。储能可以为电力系统提供多种功能;批发电价有助于引导储能运营以最低的成本实现具有最高价值的功能。

中国国家能源局最近发出指令,要求将新型储能设施(非抽水蓄能)纳入电网调度运行,这是向我们概述的改革迈出的一步。

可能需要进一步确定适当的补偿机制,例如在某些省份对此类储能设施提供的所有服务进行容量补偿,以促进这些储能设施的可持续发展和并网。

最后,仅靠增加供应不太可能成为满足中国电力需求增长的最低成本方式。提高终端使用效率和“需求响应”也有助于降低供电的总体成本。

随着中国电力市场改革的不断深入,连接多个省份的区域市场设计,以及鼓励省份间资源共享的区域资源充裕性规划,也有助于以最具成本效益和最低碳的方式满足中国不断增长的用电量和高峰需求。

The post 嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠” appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Climate change could lead to 500,000 ‘additional’ malaria deaths in Africa by 2050

Climate change could lead to half a million more deaths from malaria in Africa over the next 25 years, according to new research.

The study, published in Nature, finds that extreme weather, rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns could result in an additional 123m cases of malaria across Africa – even if current climate pledges are met.

The authors explain that as the climate warms, “disruptive” weather extremes, such as flooding, will worsen across much of Africa, causing widespread interruptions to malaria treatment programmes and damage to housing.

These disruptions will account for 79% of the increased malaria transmission risk and 93% of additional deaths from the disease, according to the study.

The rest of the rise in malaria cases over the next 25 years is due to rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns, which will change the habitable range for the mosquitoes that carry the disease, the paper says.

The majority of new cases will occur in areas already suitable for malaria, rather than in new regions, according to the paper.

The study authors tell Carbon Brief that current literature on climate change and malaria “often overlooks how heavily malaria risk in Africa is today shaped by climate-fragile prevention and treatment systems”.

The research shows the importance of ensuring that malaria control and primary healthcare is “resilient” to the extreme weather, they say.

Malaria in a warming world

Malaria kills hundreds of thousands of people every year. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 610,000 people died due to the disease in 2024.

In 2024, Africa was home to 95% of malaria cases and deaths. Children under the age of five made up three-quarters of all African malaria deaths.

The disease is transmitted to humans by bites from mosquitoes infected with the malaria parasite. The insects thrive in high temperatures of around 29C and need stagnant or slow-moving water in which to lay their eggs. As such, the areas where malaria can be transmitted are heavily dependent on the climate.

There is a wide body of research exploring the links between climate change and malaria transmission. Studies routinely find that as temperatures rise and rainfall patterns shift, the area of suitable land for malaria transmission is expanding across much of the world.

Study authors Prof Peter Gething and Prof Tasmin Symons are researchers at the Curtin University’s school of population health and the Malaria Atlas Project from the The Kids Research Institute, Australia.

They tell Carbon Brief that this approach does not capture the full picture, arguing that current literature on climate change and malaria “often overlooks how heavily malaria risk in Africa is today shaped by climate-fragile prevention and treatment systems”.

The paper notes that extreme weather events are regularly linked to surges in malaria cases across Africa and Asia. This is, in-part, because storms, heavy rainfall and floods leave pools of standing water where mosquitoes can breed. For example, nearly 15,000 cases of malaria were reported in the aftermath of Cyclone Idai hitting Mozambique in 2019.

However, the study authors also note that weather extremes often cause widespread disruption, which can limit access to healthcare, damage housing or disrupt preventative measures such as mosquito nets. These factors can all increase vulnerability to malaria, driving the spread of the disease.

In their study, the authors assess both the “ecological” effects of climate change – the impacts of temperature and rainfall changes on mosquito populations – and the “disruptive” effects of extreme weather.

Mosquito habitat

To assess the ecological impacts of climate change, the authors first identify how temperature, rainfall and humidity affect mosquito lifecycles and habitats.

The authors combine observational data on temperature, humidity and rainfall, collected over 2000-22, with a range of datasets, including mosquito abundance and breeding habitat.

The authors then use malaria infection prevalence data, collected by the Malaria Atlas Project, which describes the levels of infection in children aged between two and 10 years old.

Symons and Gething explain that they can then use “sophisticated mathematical models” to convert infection prevalence data into estimates of malaria cases.

Comparing these datasets gives the authors a baseline, showing how changes in climate have affected the range of mosquitoes and malaria rates across Africa in the early 21st century.

The authors then use global climate models to model future changes over 2024-49 under the SSP2-4.5 emissions pathway – which the authors describe as “broadly consistent with current international pledges on reduced greenhouse gas emissions”.

The authors also ran a “counterfactual” scenario, in which global temperatures do not increase over the next 25 years. By comparing malaria prevalence in their scenarios with and without climate change, the authors could identify how many malaria cases were due to climate change alone.

Overall, the ecological impacts of climate change will result in only a 0.12% increase in malaria cases by the year 2050, relative to present-day levels, according to the paper.

However, the authors say that this “minimal overall change” in Africa’s malaria rates “masks extensive geographical variation”, with some areas seeing a significant increase in malaria rates and others seeing a decrease.

Disruptive extremes

In contrast, the study estimates that 79% of the future increase in malaria transmission will be due to the “disruptive” impacts of more frequent and severe weather extremes.

The authors explain that extreme weather events, such as flooding and cyclones, can cause extensive damage to housing, leaving people without crucial protective equipment such as mosquito nets.

It can also destroy other key infrastructure, such as roads or hospitals, preventing people from accessing healthcare. This means that in the aftermath of an extreme weather event, people face a greater risk of being infected with malaria.

The climate models run by the study authors project an increase in “disruptive” extreme weather events over the next 25 years.

For example, the authors find that by the middle of the century, cyclones forming in the Indian Ocean will become more intense, with fewer category 1 to category 4 events, but more frequent category 5 events. They also find that climate change will drive an increase in flooding across Africa.

The study finds that without mitigation measures, these disruptive events will drive up the risk of malaria – especially in “main river systems” and the “cyclone-prone coastal regions of south-east Africa”.

Between 2024 and 2050, 67% of people in Africa will see their risk of catching malaria increase as a result of climate change, the study estimates.

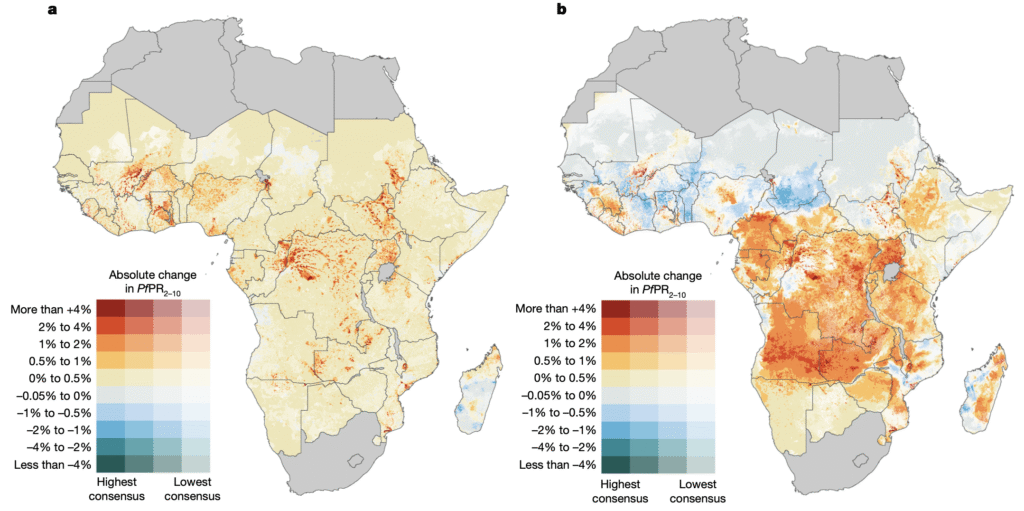

The map below shows the percentage change in malaria transmission rate in the 2040s due to the disruptive impacts of climate change alone (left) and a combination of the disruptive and ecological impacts (right), compared to a scenario in which there is no change in the climate. Red and yellow indicate an increase in malaria risk, while blue indicates a reduction.

Colours in lighter shading indicate lower model confidence, while stronger colours indicate higher model confidence.

The maps show that the “disruptive” effects of climate change have a more uniform effect, driving up malaria risk across the entire continent.

However, there is greater regional variation when these effects are combined with “ecological” drivers.

The authors find that warming will increase malaria risk in regions where the temperature is currently too low for mosquitoes to survive. This includes the belt of lower latitude southern Africa, including Angola, southern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Zambia, as well as highland areas in Burundi, eastern DRC, Ethiopia, Kenya and Rwanda.

Meanwhile, they find that warming will drive down malaria transmission in the Sahel, as temperatures rise above the optimal range for mosquitoes.

Rising risk

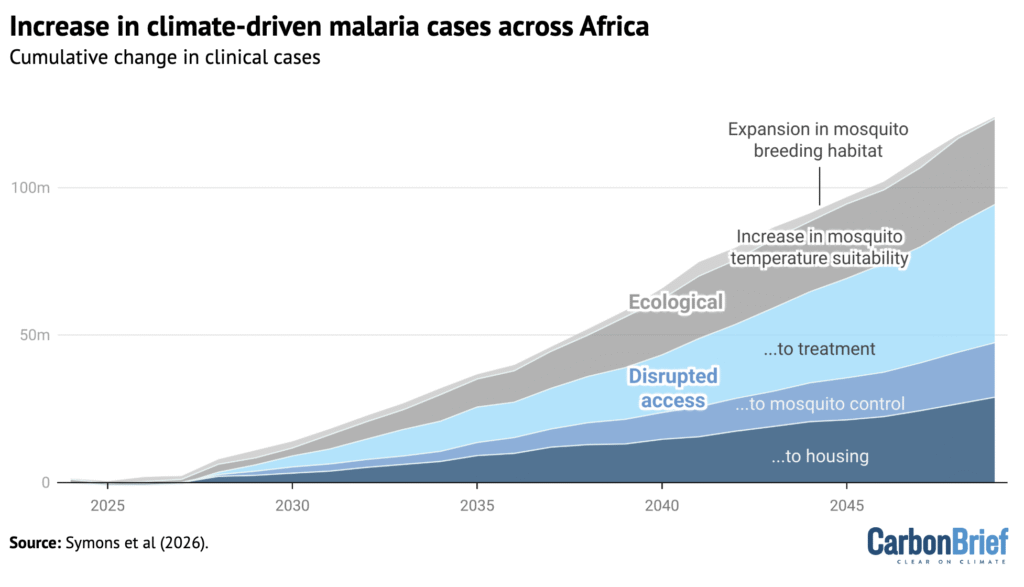

The combined “disruptive” and “ecological” impacts of climate change will drive an additional 123m “clinical cases” of malaria across Africa, even if the current climate pledges are met, the study finds.

This will result in 532,000 additional deaths from malaria over the next 25 years, if the disease’s mortality rate remains the same, the authors warn.

The graph below shows the increase in clinical cases of malaria projected across Africa over the next 25 years, broken down into the different ecological (yellow) and disruptive (purple) drivers of malaria risk.

However, the authors stress that there are many other mechanisms through which climate change could affect malaria transmission – for example, through food insecurity, conflict, economic disruption and climate-driven migration.

“Eradicating malaria in the first half of this century would be one of the greatest accomplishments in human history,” the authors say.

They argue that accomplishing this will require “climate-resilient control strategies”, such as investing in “climate-resilient health and supply-chain infrastructure” and enhancing emergency early warning systems for storms and other extreme weather.

Dr Adugna Woyessa is a senior researcher at the Ethiopian Public Health Institute and was not involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief that the new paper could help inform national malaria programmes across Africa.

He also suggests that the findings could be used to guide more “local studies that address evidence gaps on the estimates of climate change-attributed malaria”.

Study authors Symons and Gething tell Carbon Brief that during their study, they interviewed “many policymakers and implementers across Africa who are already grappling with what climate-resilient malaria intervention actually looks like in practice”.

These interventions include integrating malaria control into national disaster risk planning, with emergency responses after floods and cyclones, they say. They also stress the need to ensure that community health workers are “well-stocked in advance of severe weather”.

The research shows the importance of ensuring that malaria control and primary healthcare is “resilient” to the extreme weather, they say.

The post Climate change could lead to 500,000 ‘additional’ malaria deaths in Africa by 2050 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate change could lead to 500,000 ‘additional’ malaria deaths in Africa by 2050

Greenhouse Gases

Cropped 28 January 2026: Ocean biodiversity boost; Nature and national security; Mangrove defence

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter. Subscribe for free here. This is the last edition of Cropped for 2025. The newsletter will return on 14 January 2026.

Key developments

High Seas Treaty enters force

OCEAN BOOST: The High Seas Treaty – formally known as the “biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction”, or “BBNJ” agreement – entered into force on 17 January, following its ratification by 60 states, reported Oceanographic Magazine. The treaty establishes a framework to protect biodiversity in international waters, which make up two-thirds of the ocean, said the publication. For more, see Carbon Brief’s explainer on the treaty, which was agreed in 2023 after two decades of negotiations.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

DEEP-SEA MINING: Meanwhile, the US – which is not a party to the BBNJ’s parent Law of the Sea – is pushing on with an effort to accelerate permitting for companies wanting to hunt for deep-sea minerals in international waters, reported Reuters. The newswire described it as a “move that is likely to face environmental and legal concerns”.

UK biodiversity probe

SECURITY RISKS: The global decline of biodiversity and potential collapse of ecosystems pose serious risks to national security in the UK, a report put together by government intelligence experts has concluded, according to BBC News. The report was due to be published last autumn, but was “suppressed” by the prime minister’s office over fears it was “too negative”, said the Times.

COLLAPSE CONCERNS: Following a freedom-of-information (FOI) request, the government published a 14-page “abridged” version of the report, explained the Times. A fuller version seen by both the Times and Carbon Brief looked in detail at the potential security consequences of ecosystem collapse, including shifting global power dynamics, more migration to the UK and the risk of “protests over falling living standards”.

News and views

- OZ BUSHFIRES: Bushfires continued to blaze in Victoria, Australia, amid record-breaking heat, said the Guardian. A recent rapid attribution analysis found that the “extreme” Australian heat in early January was made around five times more likely by fossil-fuelled climate change.

- MERCO-SOURED: On 17 January, the EU signed its “largest-ever trade accord” with the Mercosur bloc of countries – Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay – after 25 years of negotiations, per Reuters. On 21 January, amid looming new US sanctions, EU lawmakers voted to send the pact to the European Court of Justice, which could delay the deal by almost two years, according to the New York Times.

- SOY IT ISN’T SO: Meanwhile, the Guardian reported that UK and EU supermarkets have “urged” traders who had “abandoned” the Amazon soya moratorium to stick to its core principles: “not to source the grain from Amazon land cleared after 2008”.

- WATER ‘BANKRUPTCY’: A new UN report warned that the world is facing irreversible “water bankruptcy” caused by overextracting water reserves, along with shrinking supplies from lakes, glaciers, rivers and wetlands, Reuters reported. Lead author Prof Kaveh Madani told the Guardian that the situation is “extremely urgent [because] no one knows exactly when the whole system would collapse”.

- KRUGER UNDER WATER: Flood damages to South Africa’s Kruger National Park could “take years to repair” and cost more than $30m, said the country’s environment minister, quoted in Reuters. Rivers running through the park “burst their banks” and submerged bridges, with “hippos seen…among treetops”, it added.

- FORESTS VS COPPER: A Mongabay report examined how “community forests stand on the frontline” of critical-minerals mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s copper-cobalt belt.

Spotlight

Nature’s coast guard, with backup

This week, Cropped speaks to the lead author of a new study that looks at how – and where – mangrove restoration can be best supported across the world.

Along Mumbai’s smoggy shoreline, members of the city’s Indigenous Koli community wade through the mangroves at dawn to catch fish. Behind their boats, giant industrial cranes whir to life, building new stretches of snaking coastal highway that blot out the horizon.

Mumbai’s mangrove cover is possibly the highest for any major city. With their tangled, stilt roots, mangrove species serve as a natural defence for a city that experiences storm surges and urban flooding every year. These events disproportionately affect the city’s poor – particularly its fishing communities.

This mangrove buffer is being increasingly threatened, as the city chooses coastal roads and other large development projects over green cover, despite protests. But can green and grey infrastructure coexist to protect vulnerable communities in a warming world?

A new global-scale assessment published last week tallied the benefits of mangrove restoration for flood risk reduction, factoring in future climate change, development and poverty.

It advanced the idea of “hybrid” coastal defence measures. These combine pairing tropical ecosystems with modern, engineered defences for sea level rise, such as dykes and levees.

When Carbon Brief contacted lead author and climate scientist Dr Timothy Tiggeloven of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, he was in Kagoshima in Japan, home to the world’s northernmost mangrove forests. Why combine mangroves and dykes? Tiggeloven explained:

“Mangroves are like active barriers: they reduce incoming energy from waves, but they will not stop the water coming in from storms, because water can flow through the branches. But wave energy can still be overtopped. So if you reduce wave energy via mangroves and have dykes behind this, they very much have a synergy together and we wanted to quantify the benefits for future adaptation.”

According to the study, if mangrove-dyke systems were built along flood-prone coastlines, mangrove restoration could reduce damages by $800m a year, with an overall return-on-investment of up to $125bn.

It could also protect 140,000 people a year from flood risk – and 12 times that number under future climate change and socioeconomic projections, the study said.

According to the study, south-east Asia could reap the “highest absolute benefits” from mangrove restoration under current conditions. Countries that could see the “highest absolute potential risk reduction” – considering future climate damages in 2080 – are Nigeria ($5.6bn), Vietnam ($4.5bn), Indonesia ($4.3 bn), and India ($3.8bn), it estimated.

Maharashtra – which Mumbai serves as the state capital for – is one of two subnational regions globally that could reap the largest benefits of restoration.

Tiggeloven emphasised that the goal of the study was to examine how restoration impacts people, “because if we’re looking only at monetary terms, we’re only looking at large cities with a lot of assets”, he told Carbon Brief.

A pattern that his team found across multiple countries was that people with lower incomes are disproportionately living in flood-prone coastal areas where mangrove restoration is suitable. He elaborated:

“Wealthier areas might have higher absolute damages, but poor communities are more vulnerable, because they lack alternatives to easily relocate or rebuild, so the relative impact on their wellbeing is much greater.”

Poorer rural coastal communities with fewer engineered protections, such as sea walls, could benefit the most from restoration as an adaptive measure, the study found. But as the study’s map showed, there are limits to restoration. Tiggoloven concluded:

“We also should be very careful, because mangroves cannot grow anywhere. We need to think ‘conservation’ – not only ‘restoration’ – so we do not remove existing mangroves and make room for other infrastructure.”

Watch, read, listen

DU-GONE: A feature in the Guardian examined why so many dugongs have gone missing from the shores of Thailand.

WILD LONDON: Sir David Attenborough explored wildlife wonders in his home city of London. The one-off documentary is available in the UK on BBC iPlayer.

GREAT BARRIER: A Vox exclusive photo-feature looked at the “largest collective effort on Earth ever mounted” to protect Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

‘SURVIVAL OF THE SLOWEST’: A new CBC documentary filmed species – from sloths to seahorses – that “have survived not in spite of their slowness, but because of it”.

New science

- Including carbon emissions from permafrost thaw and fires reduces the remaining carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5C by 25% | Communications Earth and Environment

- Penguins in Antarctica have radically shifted their breeding seasons in response to rising temperatures | Journal of Animal Ecology

- Increasing per-capita meat consumption by just one kilogram a year is “linked” to a nearly 2% increase in embedded deforestation elsewhere | Environmental Research Letters

In the diary

- 31 January: Deadline for inputs on food systems and climate change for a report by the UN special rapporteur on climate change

- 1 February: Costa Rica elections

- 2-6 February: First session of the plenary of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Panel on Chemicals, Waste and Pollution | Geneva

- 2-8 February: Twelfth plenary session of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services | Manchester, UK

- 5 February: Future Food Systems Summit | London

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz. Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 28 January 2026: Ocean biodiversity boost; Nature and national security; Mangrove defence appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 28 January 2026: Ocean biodiversity boost; Nature and national security; Mangrove defence

Greenhouse Gases

Expensive gas still biggest driver of high UK electricity bills, says UKERC

High gas prices are responsible for two-thirds of the rise in household electricity bills since before the global energy crisis, says the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC).

The new analysis, from one of the UK’s foremost research bodies on energy, flatly contradicts widespread media and political narratives that misleadingly seek to blame climate policies for high bills.

Kaylen Camacho McKluskey, research assistant at UKERC, tells Carbon Brief that despite “misleading claims” about policy costs, gas prices are the main driver of high bills. She says:

“While the story of what has driven up GB consumer electricity bills is often largely attributed to policy costs, our analysis shows that this is not the case. Volatile, gas-linked market prices – not green policies, as some misleading claims have suggested – dominate the real-terms increase in bills since 2021.”

In its 2025 review of UK energy policy, published today, UKERC says that annual electricity bills for typical households have risen by £166 since 2021.

It says that, after adjusting for inflation, some two-thirds of this increase (£112) is due to higher wholesale gas prices, as shown in the figure below.

(This analysis does not account for the recent surge in wholesale gas prices, which, in a matter of days, have jumped by around 40% in the UK and 140% in the US.)

UKERC estimates that, despite only supplying a third of the country’s electricity, gas-fired generators set the wholesale price of power around 90% of the time in 2025.

(This is slightly lower than widely cited earlier estimates, published in 2023 and covering 2021, which found gas was setting power prices 97% of the time.)

A surge of new clean power means that gas would only set wholesale power prices 60% of the time by 2029, UKERC says, adding that this would cut the nation’s exposure to “gas price shocks”.

It finds that new renewable projects set to come online over the next three years could cut wholesale power prices by 8% from current levels.

UKERC argues that the government could “strengthen…these downward trends” by shifting older renewable plants onto fixed-price “contracts for difference” (CfDs).

These older schemes, built under a policy known as the “renewables obligation”, are paid a top-up subsidy in addition to the wholesale power price, linking their receipts to high gas prices.

Newer renewable projects with CfDs get a fixed price, which is not linked to wholesale electricity prices or the price of gas power that drives it.

Prof Rob Gross, UKERC director says in a press release that “unpredictable global gas prices still dominate our power market”. He continues:

“The link between the wholesale price of gas and electricity prices continues to be the most significant factor in the price increases consumers have seen over the last few years. Government took action on some policy costs in [last year’s] budget and ongoing policies will weaken the link to gas prices. But more could be done to help ensure that the stable prices offered by renewables flow through to consumer bills.”

The UKERC analysis shows that rising network charges, linked to investments in expanding the electricity grid as well as balancing supply and demand in real time, were the second-largest contributor to the rise in bills since 2021.

Significant further grid investments are set to add further pressure on bills over the next few years. However, energy regulator Ofgem says these investments will cut bills relative to the alternative.

Policy costs are only the third-largest driver of current high bills, according to UKERC’s analysis. It says these were linked to just 12% of the rise for typical households, or £19 per year.

It is commonly argued that rising policy costs are certain to raise bills, but this tends to ignore the interplay between CfDs and wholesale power prices.

The record-breaking recent government auction for CfDs is expected to be roughly “cost neutral” for bills, potentially even generating consumer savings of £1bn a year by 2035.

As UKERC explains, this is because new renewable projects will receive CfD payments and may result in higher network costs, but they also cut wholesale power prices. A full analysis of the overall impact on bills must take all of these factors into account.

The UKERC report aligns with another recent analysis from thinktank Nesta, which said that, while there was a pressing need to look at future cost pressures from network and policy charges, “it is clear that gas is still the main source of our high energy bills to date”. It added:

“It is still true that higher gas prices are the main reason for higher energy bills for most British households when you look at the whole bill. Gas is not the only culprit, but it is still the biggest one.”

The post Expensive gas still biggest driver of high UK electricity bills, says UKERC appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Expensive gas still biggest driver of high UK electricity bills, says UKERC

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility