At COP28 in Dubai, Carbon Brief’s Anika Patel spoke with Prof Zou Ji, CEO and president of the Energy Foundation China, to discuss China’s approach to its energy transition.

This wide-ranging interview covers China’s stance on fossil fuels, issues-based alliances and energy efficiency pledges at COP28, pathways to the country growing its renewable power generation and what China has learned from Germany’s energy transition. It is transcribed in full below, following a summary of key quotes.

Energy Foundation China is a professional grantmaking organisation dedicated to China’s sustainable energy development. Prof Zou has years of experience in economics, energy, environment, climate change, and policymaking, having previously served as a deputy director general of China’s National Center for Climate Change Strategy and International Cooperation, under the government’s national development and reform commission (NDRC).

He was also a key member of the Chinese climate negotiation team leading up to the Paris Agreement, and has been a lead author for several assessment reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- On why China did not join the pledge to triple renewables and double efficiency: “[Before COP28] we have not seen [it laid out] very clearly which year should be the base year [from which tripling renewables should be calculated]. Should it be 2020? Should it be 2022? This might seem to be technical but, [in] the past two years, global development of renewables, especially in China, [have been significantly boosted, and so]…the difference in targets might be very significant.”

- On signing pledges at COP: “If you look at the whole history of the COP…I do not [remember] China joining any alliances. I have never seen that…As a party, China [is only concerned with] official procedures, waiting for a legal framework of the UNFCCC or the Paris Agreement.”

- On China’s commitment to decarbonisation: “If you look back at history, there have been very few cases that show China [first making] and then [giving up] a commitment. This is not the political culture in China.”

- On China’s electricity consumption: “For low-income level groups, although their income has not grown very much, their consumption preferences and mindsets – especially for younger generations of consumers – mean they are more willing to use electricity [than previous generations].”

- On comparisons of China to the EU and US: “There is a structural [difference] compared to the [energy mix] in Europe and the US. The majority of energy use [in China] has been for industrial production, rather than for residential [use]…In China, the average power consumption per capita is around 6,000 kilowatt-hours (kWh), compared to 8,000kWh in Europe and over 12,000kWh in the US.”

- On energy efficiency: “Physically, I think China has become better and better [in terms of] its efficiency, but, economically, this cannot produce as high a value-add as Europe and the US in monetary terms.”

- On fossil fuel phaseout: “I would like to see…[China] very quickly enlarging its renewable capacity. Only if [there is] adequate capacity and generation of renewables can this lead to a real phasing out or phasing down of fossil fuels.”

- On ensuring more renewables uptake: “We have raised the share of renewable power generation from seven, eight, nine per cent to today’s 16%. This is progress, but it is not quick enough or large enough. We want to push the grid companies…to do more and do it faster.”

- On the power of distributed renewables: “We should also consider…creat[ing] another, totally new power system. This would be a sort of nexus of a centralised and decentralised grid system…If [the central grid] is having difficulties [increasing renewable generation], and if these are very challenging to overcome, then let’s [shift] to a lot of microgrids.”

- On distributed renewables growth: “Today, the share of distributed [renewables] is still lower than centralised renewables. But the incremental [distributed] renewables growth has become higher than growth of centralised renewables in the past year or two, and I would assume this will remain a trend in the future.”

- On substituting fossil fuels with renewables: “Relying only on solar and the wind [means] you need not rely on imported oil or gas. And so, gradually, you will de-link your energy use from coal [and] from fossil fuels.”

- On the need for CCUS: “In some sectors, like, for example, iron and steel, cement, chemicals and petrochemicals, we do need carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS), because it is very difficult to phase out coal or carbon dioxide [completely].”

- On CCUS in the power sector: “I have mixed feelings about CCUS for the power sector. I have an ideal vision that we can reach real zero emissions in these sectors through a more developed grid system, with more connectivity across provinces or regions and the use of AI technology.”

Carbon Brief: Could you give an overview of what your expectations are for COP28?

Zou Ji: It might be a little early to make a judgement [on] what outcomes this COP can reach, but we do know what the key issues here are…[The] global stocktake (GST) is the core issue for this COP as it is the first time it has taken place since the Paris Agreement …But for the GST there are different levels [at which we need] to understand [the process and]…its outcome. Number one, [in terms of] the scope of GST, what should we take stock [of]? Many colleagues, especially colleagues from Europe and maybe also from the US – I mean industrialised countries – would like to concentrate more on mitigation…We still have a significant gap…[to fill] to achieve the 1.5C target. The gap [is] there, and we need to enhance our ambition to close the gap. So this is a major concern…in the GST.

But meanwhile, we see some other parties, [such as] the so-called [like-minded] developing country [LMDC] group… the Alliance of Small Island States and Least Developed Countries group, [which are] mainly located in Africa. [These groups] are very keen to [address] the gap in financial support for capacity building and technology transfer, in short, means of implementation.

And there has been, since [COP26 in] Glasgow, I think, a very specific financial issue: the loss and damage fund. Together with some general financial issues like developed countries mobilis[ing] $100bn each year by 2023, this will continue to be a concern. But…we also have other issues, more specific issues like the tripling of renewables and doubling efficiency and… [procedure-related] issues like transparency. [There are] a lot of issues!

Before COP we have seen…official statements from Europe, from the US and also from China – especially the joint Sunnylands statement – [which is] relevant to China-US cooperation in COP28 and…can [give us] some very initial expectations on the outcome.

[Taking the GST as an example], I would assume there will be a political decision by all the parties [to say] they recognise the significant gap for achieving well-below 2C, [following] the Paris Agreement language. But [there is an] even larger gap for 1.5C. This should be one [thing] we could expect [to see appear in the final text], but certainly I think there must be some tough negotiations on the scope of the GST: especially [on if we] should include…issues [such as] adaptation, financial support to developing countries, technology transfer, capacity building, etc…The negotiations will be very tough, but it is a long debate.

[Another issue to watch is the] tripling renewables and doubling efficiency [pledge]. I would say [that the issue has received]…endorsement from the G20 and the Sunnylands statement. But in those two statements…we have not seen [it laid out] very clearly which year should be the base year. Should it be 2020? Should it be 2022? This might seem to be technical but, [in] the past two years, global development of renewables, especially in China, [have been significantly boosted]… So [depending on which year is picked as the base year,] the difference in targets might be very significant.

And then it is packaged together with [a more defined] target…[to] not only [focus on the] tripling [of renewables] but also [to focus on] the total amount of the capacity of renewables…11,000GW [gigawatts] has been proposed. If this is the case, [meaning that] the base year is 2020…then, [from some negotiators’ perspectives] this might be a different understanding of the definition of the target from the one [proposed] before the COP. And then, this may lead to some parties hesitat[ing] to make an official commitment on that. I know you might be very interested in China’s position on that issue.

CB: You read my mind.

ZJ: I would try to understand it in this way. If you look at the whole history of the COP…I do not [remember] China joining any alliances [Prof Zou here means issue-based alliances or pledges]. I have never seen that. That means that[,]…as a party, China only focuses on official procedures, waiting for a legal framework of the UNFCCC or the Paris Agreement. And if you look at different initiatives, [such as the] climate ambition alliance, [global] renewables alliance, etc – for the moment, they have not readied a legal framework. So now…[the pledges are] informal, without official or legal commitments. So, I cannot find evidence [of China joining informal alliances in this way].

Certainly I do not have any assessments whether China should…or should not [join the pledge to triple renewable energy and double energy efficiency]. But this is the history…of China’s engagement in UNFCCC, the Paris Agreement [and] the Kyoto Protocol…If China makes [such] a commitment, this would be somewhat surprising [from a historical perspective].

[Secondly,] maybe this reflects the difference of political systems and…policymaking in different political regimes or cities, especially between China and Europe and the United States. As you know, in Europe and the US you have election[-based] regimes or systems – every four or five years you will elect a different parliament, a different cabinet, a different president or a different prime minister, etc. Their term might be short or it might be long, depending on the results of the election. That means that there is no guarantee for one party or for one policymaker to stay in power for a long time. It might be two terms, it might be three terms. But in China, the political assumption is [that] the communist party will be in power forever. [No-one would assume that] next year, or next term, we will have another party leading the country.

My observation is [that] Chinese policymakers are very cautious [about] making commitments, not only because of concerns around the challenges and difficulty of achieving this commitment. They would say: “If I make the commitment, this should be something I must [achieve].” [This is] because they make the decision or commitment for a single party. No matter [which] generation of leader [made the commitment], the commitment comes from the same party…So that partially [explains] why China seems to be very careful to make even a long-term commitment.

Just to take a very immediate example, the US made a commitment on the Kyoto Protocol during the Clinton administration, but only [on behalf of] the White House. When [power] turned to the Bush administration in the early 2000s, the Bush administration said [they] will not submit that proposal to congress, because [they] knew it would not be approved…And then [eventually] the US gave up [trying] to ratify the Kyoto Protocol.

This is the first case, and unfortunately, we see another case in the Trump administration. The Obama administration…signed the Paris Agreement. But…[then] Trump became president and Trump said the US will withdraw from the Paris Agreement. And this [type of turbulence] is something, in fact, I take for granted, given [my] understanding of the US political system. But this is not the case in China.

Thirdly, it might be a matter of political culture. For the Chinese, normally, [as I said]…if they make a commitment, the commitment…is something they must [achieve]. Normally they will not…just make the commitment to ‘talk [big]’ and then, after several years, give up or ‘forget’ [about it]. Normally, China will remember [its] commitments and will achieve [them], [on the] basis of trust. So, China puts very high [importance] on achieving these commitments, [which] leads to some difficulties for the Chinese government to make commitments. If you look back at history, there have been very few cases that show China [first making] and then [giving up] a commitment. This is not the political culture in China. But this is my understanding, not a standardised or official interpretation!

CB: I was having a conversation with another academic earlier today, and they offered an additional explanation – that recent economic troubles might be an added factor increasing caution towards committing to targets in China. Would you agree with that?

ZJ: It’s not easy to simply answer yes or no, agree or disagree. But I would say yes. The uncertainty of growth in the past years, especially since the pandemic, seems to [have made] things a little bit…complicated, especially in terms of carbon intensity.

In past years, the [economic] growth rate has become lower and lower – even lower than expectations. But carbon emissions continue to increase. Several years ago, the common understanding was that if the growth rate stays at a very high level, the economy will grow over time, and then emissions will grow over time. But this time, we saw that growth was very slow, but emissions continued to grow. But I would like to try to look at this in more detail, to identify the driving force behind [this]. Why have we had a lower growth rate in the past year, but carbon emissions, coal use and also energy use have continued to grow?

[In this case], we had better look at energy use per capita, and especially electricity use per capita. Although the growth rate is very low, the base amount of power use per capita was also very low in the past. For low-income level groups, although their income has not grown very much, their consumption preferences and mindsets, especially for younger generations of consumers, mean they are more willing to use electricity…Just look at the energy use performance of low-income groups in rural areas.

In urban areas, blue collar [workers] have better living conditions – they have air conditioners, better heating [and can access better options for] travel. Although their income level continues to be very low, their consumption behaviour has changed over time…Everybody [now] has a mobile phone and connection to the internet…They saw [examples of how to live a better life] from people in the middle income [band]. They saw this from advertisements, from movies, from TV programmes, etc…Compared to their fathers’ generation, [who had a] similar income level, their pursuit of a higher quality of life [could be a reason why] today [they] have a higher level of energy consumption. This is one interpretation [of the data], but it can be proven by many pieces of evidence.

Another [interpretation] is if you look at China’s mix of energy use, in terms of total amount and in terms of per capita, there is a structural [difference] compared to the [energy mix] in Europe and the US. The majority of energy use [in China] has been for industrial production, rather than for residential [use]. And given what I just mentioned, [in terms of] the change of consumption behaviour…[The effects are] marginal [if] they increase their consumption of energy. In China, the average power consumption per capita is around 6,000 kilowatt-hours (kWh), compared to 8,000kWh in Europe and over 12,000kWh in the US.

CB: Does that have an implication for why China talks about energy intensity, whereas Europe and the US talk about energy efficiency?

ZJ: Yes. In China, the general indicator is energy intensity per unit of GDP. But when you talk about energy efficiency, what is the indicator? You have physical indicators, for example, energy use per tonne of iron, steel, ammonia or cement. This is one way to measure efficiency. Another way is just to [calculate it] per unit of GDP, which shows the major sources of money in your economy. Physically, I think China has become better and better [in terms of] its efficiency, but economically this cannot produce as high a value-add as Europe and the US in monetary terms. So that changes things, especially given two [factors]. One is the lower and lower GDP growth rate, which makes carbon intensity higher. Another is the chang[ing] foreign exchange situation in recent years. The raising of interest rates by the US Federal Reserve makes US dollars more expensive, increasing foreign exchange rates which then enlarges the monetary GDP gap, making Chinese GDP [in dollar terms] fall and carbon intensity rise.

So, there are several variables [affecting this decision], but we should also not ignore the real improvements to efficiency [in China], measured by physical indicators. I saw slightly slower progress in efficiency improvements, but maybe those are the matter of measurement.

CB: That’s always the fun fine print. Going back to the scope of the GST at COP28, how would you interpret China’s position on the ideal language around fossil fuels?

ZJ: I retired from the delegation eight years ago, so [I can’t say for sure] about the ideal language! But, maybe we can revisit the language from the Sunnylands statement. There is a specific paragraph talking about recognising the global tripling of renewables and the doubling of efficiency…[which is] then followed by several phrases mentioning that China and the US should accelerate the deployment of renewables…to substitute fossil fuels, including coal, oil and gas. So, if I were in the delegation, I should look at fossil fuels as a whole. Certainly, we should accelerate the process to phase down or phase out fossil fuels.

I mean, in China, it is mainly the matter of coal. But in Europe and the US, it is mainly the matter of oil and gas. According to an International Energy Agency (IEA) report, in the past decade, the whole world moved very slowly to phase out coal, oil and gas. In China, the majority issue is coal, but in Europe we saw some positive but very small changes when you look at the share of fossil fuels – [particularly] oil and gas. Same in the US.

So, what about the pace of phasing out or phasing down coal, oil or gas? Different countries have different agendas here. So maybe fossil fuels should be covered for every country. [But] I would like to see…[China] very quickly enlarging its renewable capacity. Only if [there is] adequate capacity and generation of renewables can this lead to a real phasing out or phasing down of fossil fuels. In this sense, I think these are the same story for all the countries, for Europe, for the US and also for China.

CB: We published analysis recently saying that fossil fuels in China might enter a structural decline next year because of China’s renewable build out. However, as we all know, there are challenges facing the grid, I think not only with intermittency but also with developing market mechanisms. How optimistic are you that China will be able to overcome these constraints in the power grid and make renewable energy more widely consumed?

ZJ: This is a very good question. There are several ways to figure out the transmission issue to support broader and deeper use of renewables. Number one, as you know, we have a very unbalanced geographical distribution of renewables. Northern and north-western China has very rich renewable resources, especially solar and wind power. But the most dense centres of energy use are located in the eastern and southern part of China. This requires that we generate renewable power and then transmit [it] from northern and western China to eastern, southern and south-eastern China. This will require a very long-distance transmission grid, [covering] two-, three- or even four thousand kilometres. [That comes at] a very high expense, [creating a] high cost for transmission.

Normally, we have a very rough estimate that [transmission will cost] around 0.1 yuan per kilowatt-hour for every thousand kilometres. So how do we overcome [these higher costs]? One way is to optimise the distribution and allocation of remote renewable resources. For example, [we could] transmit [power] from the closest places, [such as transmitting power from] Inner Mongolia province…to the eastern part [of China]. This is one way. China now has [developed] an ultra-high voltage [UHV] transmission system, which enables long-distance transmission, and we rely on that technology. We have had some engineering pilots [for UHV transmission in place] already, from Qinghai province to Henan province…[and] from Baihetan in Sichuan province to Jiangsu province. There are several [other] transmission grids under construction.

Another bottleneck is the capacity of the grid to absorb renewables. To my knowledge, in the past few years, we have made some progress, but this has been very limited. We have raised the share of renewable power generation from seven, eight, nine percent to today’s 16%. This is progress, but it is not quick enough or large enough. We want to push the grid companies – State Grid and Southern Grid – to do more and do it faster.

What we want to push [can be] compared to a benchmark [set by the] German grid. As you may know, Germany’s grid is one of the most advanced grids in the world, in terms of featuring a higher share of renewable generation – it can have up to 40% or even 50% of generated power come from solar and wind power. But what I’m thinking about now is if China can catch up and fill the gap between its grid and the German grid.

I’ve heard a lot of different opinions from power experts, [which] I will not go into detail here – it is too technical! But one long-term consideration to overcome…is the higher and higher marginal cost of raising the share of renewables in the German grid. This means [progress] to further enlarge the share of renewables in their grid has become slower. If this is the case for Germany today, this might also be the case for China tomorrow. That means that there might be some physical limitations [to having a higher share of renewables] in the current power system and the grid system.

But certainly the first step for China should be to close the gap between its current performance and Germany’s performance. Beyond that, a 40-50% [renewables] share is not enough for carbon neutrality or for [meeting the target of] 1.5C. We want to have more. What is the way out? We should also consider… creat[ing] another, totally new power system. This would be a sort of nexus of centralised and decentralised grid systems…If [the central grid] is having difficulties [increasing renewable generation], and if these are very challenging to overcome, then let’s [shift] to a lot of microgrids, together with a distribution grid, which would act as a lower level of the grid.

[To do this] you need to figure out a lot of technological issues, including [the use of] transformers and changing the [grid] system. To allow [for] more and more distributed renewables, it should not be necessary [for them] to be connected to the centralised grid system. [Instead, microgrids] should just have to connect with each other, with [households] having their own rooftop solar [panels] which are connected with each other using AI technology, etc. And if they do that, then most of [China’s] electricity [will be] generated by distributed renewables. That way, we [can] rely on the centralised grid less and less.

This might be one way to figure out today’s bottleneck, and Energy Foundation China is exploring a pilot [to trial this]. The solution is mainly applicable to rural areas…households… and also SMEs outside the central mega-cities…This might serve as the power source [that will cover] the increase in our power demand in the future. We can stop [the go-to solution being to rely on] coal or other fossil fuels, and instead from the very beginning [demand would be met through] renewables. So that is something I’m thinking about.

CB: That’s a really interesting possibility. I’m a bit of a pessimist, so an immediate question that comes to mind is that we have seen how important energy security and stability is to the general political system in China. If we have this decentralised system, would that cause nervousness among some government stakeholders?

ZJ: I would say that a distributed power system would help to raise the degree of energy security.

CB: Is that because it would be complementary to a central system, not replacing a central system?

ZJ: At the very earliest stages of the development, it would be complementary, but beyond 2030, the share of distributed renewables in the overall renewables system will become higher and higher. Today, the share of distributed [renewables] are still lower than centralised renewables. But the incremental renewables growth has become higher than growth of centralised renewables in the past year or two, and I would assume this will remain a trend in the future. Some of the obstacles to developing centralised renewables, in terms of technology, in terms of institutions, etc, means that distributed renewables have some comparative advantages [which are currently] being formed. [Renewables are] lower cost and [grant] higher energy security, relying only on solar and the wind [means] you need not rely on imported oil or gas. And so gradually, you will de-link your energy use from coal [and] fossil fuels.

… But certainly, we are in the very early stages [of] developing [such a system]. I believe, in China, all stakeholders – including government, business, academia, and NGOs like us — wish to make a collective effort to make that happen.

CB: Absolutely. I’m aware that it is very late, so I’ll leave with one last question. In two scenarios – first of all, where there is more distributed energy and a kind of constellation of these microgrids that you described, and then, secondly, in a future where perhaps, there’s a more centralised system but ever-increasing renewable capacity, do you see a role in both of these scenarios for CCUS?

ZJ: Carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) is still very controversial, among researchers and stakeholders. Especially in the power sector. But it is my understanding that in some sectors, like, for example, iron and steel, cement, chemicals and petrochemicals, we do need CCUS, because it is very difficult to phase out coal or carbon dioxide [completely]. I mean, even with the technology [coming down the pipeline], there [will still have to] be some [CO2] emissions.

Although you might be able to minimise the emission of CO2 in those fields, you cannot phase them out, only down. In [order to] achieve carbon neutrality, you have to capture those carbon emissions from those sectors. So we need CCUS for those specific sectors and technologies.

But for the power sector, I have mixed feelings about this. I have an ideal vision that, maybe, we can reach real zero emissions in these sectors through a more developed grid system, with more connectivity across provinces or regions and the use of AI technology to connect microgrids, for example, and let them trade with each other to complement each other’s peak and valley loads. This is one way out for the power sector, together with a more developed energy storage system, in the upstream, midstream and downstream ends of the power system.

My instinct is we should go in that direction [for the power sector]. We should not rely on coal for stabilising the grid system or for stabilising the whole power system. I know the mainstream thinking is we should rely on coal as the baseload for stabilising the power system. But I have a slightly different idea, that through more developed connectivity of the grid, more smart grids, together with very strong grid energy storage…If this is successful, then we would not need so much CCUS in the power sector.

I can share that the current mainstream academic understanding [is that], even though China will reach its [2060] carbon neutrality target, it will continue to have to maintain 600 gigawatts of coal-fired power plants capacity. These are the sort of estimations [we’re working with now], for the capacity [needed] to serve as the baseload to stabilise the power sector.

Maybe I’m too [optimistic] – I believe we may need some [coal] capacity there, as a backup in case of disaster, like Germany did right after the Ukraine war, when they opened several coal-fired power plants. But this doesn’t necessarily mean [that the government] will rebound the use of coal. Its function will just be as the backup.

The post The Carbon Brief Interview: Prof Zou Ji appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 23 January 2026: Trump’s Davos tirade; EU wind and solar milestone; High seas hope

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Trump vs world

TILTING AT ‘WINDMILLS’: At the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, Switzerland, Donald Trump was quoted by Reuters as saying – falsely – that China makes almost all of the world’s “windmills”, but he had not “been able to find any windfarms in China”, calling China’s buyers “stupid”. The newswire added that China “defended its wind power development” at Davos, with spokesperson Guo Jiakun saying the country’s efforts to tackle climate change and promote renewable energy in the world are “obvious to all”.

SPEECH FACTCHECKED: The Guardian factchecked Trump’s speech, noting China has more wind capacity than any other country, with 40% of global wind generation in 2024 in China. See Carbon Brief’s chart on this topic, posted on BlueSky by Dr Simon Evans.

GREENLAND GRAB: Trump “abruptly stepped back” from threats to seize Greenland with the use of force or leveraging tariffs, downplaying the dispute as a “small ask” for a “piece of ice”, reported Reuters. The Washington Post noted that, while Trump calls climate change “a hoax”, Greenland’s described value is partly due to Arctic environmental shifts opening up new sea routes. French president Macron slammed the White House’s “new colonial approach”, emphasising that climate and energy security remain European “top priorities”, according to BusinessGreen.

Around the world

- EU MILESTONE: For the first time, wind and solar generated more electricity than fossil fuels in the EU last year, reported Reuters. Wind and solar generated 30% of the EU’s electricity in 2025, just above 29% from plants running on coal, gas and oil, according to data from the thinktank Ember covered by the newswire.

- WARM HOMES: The UK government announced a £15bn plan for rolling out low-carbon technology in homes, such as rooftop solar and heat pumps. Carbon Brief’s newly published analysis has all the details.

- BIG THAW: Braving weather delays that nearly “derail[ed] their mission”, scientists finally set up camp on Antarctica’s thawing Thwaites glacier, reported the New York Times. Over the next few weeks, they will deploy equipment to understand “how this gargantuan glacier is being corroded” by warming ocean waters.

- EVS WELCOME: Germany re-introduced electric vehicle subsidies, open to all manufacturers, including those in China, reported the Financial Times. Tesla and Volvo could be the first to benefit from Canada’s “move to slash import tariffs on made-in-China” EVs, said Bloomberg.

- SOUTHERN AFRICA FLOODS: The death toll from floods in Mozambique went up to 112, reported the African Press Agency on Thursday. Officials cited the “scale of rainfall” – 250mm in 24 hours – as a key driver, it added. Frontline quoted South African president Cyril Ramaphosa, who linked the crisis to climate change.

$307bn

The amount of drought-related damages worldwide per year – intensified by land degradation, groundwater depletion and climate change – according to a new UN “water bankruptcy” report.

Latest climate research

- A researcher examined whether the “ultra rich” could and should pay for climate finance | Climatic Change

- Global deforestation-driven surface warming increased by the “size of Spain” between 1988 and 2016 | One Earth

- Increasing per-capita meat consumption by just one kilogram a year is “linked” to a nearly 2% increase in embedded deforestation elsewhere | Environmental Research Letters

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

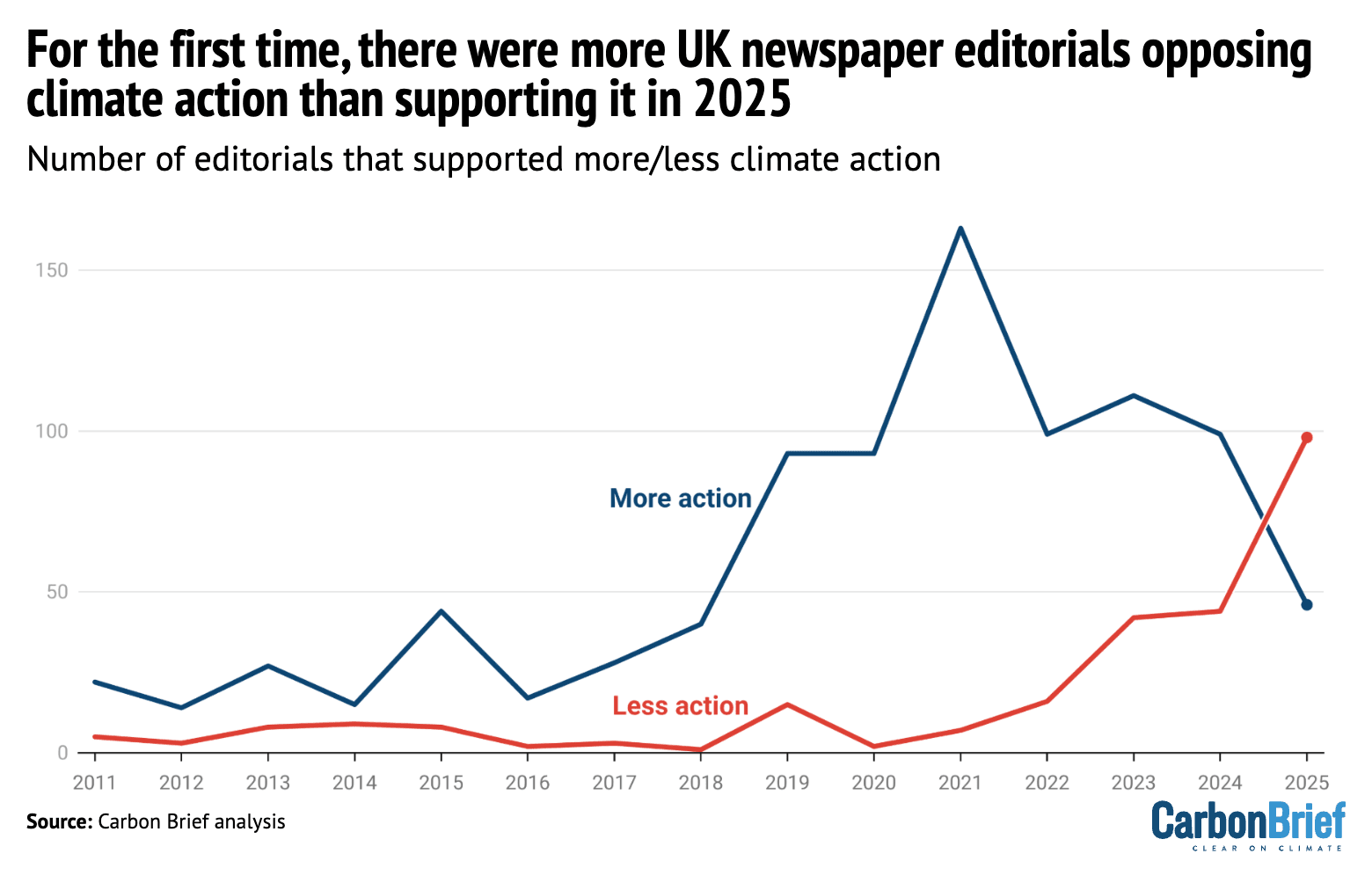

For the first time since monitoring began 15 years ago, there were more UK newspaper editorials published in 2025 opposing climate action than those supporting it, Carbon Brief analysis found. The chart shows the number of editorials arguing for more (blue) and less (red) climate action between 2011-2025. Editorials that took a “balanced” view are not represented in the chart. All 98 editorials opposing climate action were in right-leaning outlets, while nearly all 46 in support were in left-leaning and centrist publications. The trend reveals the scale of the net-zero backlash in the UK’s right-leaning press, highlighting the rapid shift away from a political consensus.

Spotlight

Do the oceans hold hope for international law?

This week, Carbon Brief unpacks what a landmark oceans treaty “entering into force” means and, at a time of backtracking and breach, speaks to experts on the future of international law.

As the world tries to digest the US retreat from international environmental law, historic new protections for the ocean were quietly passed without the US on Saturday.

With little fanfare besides a video message from UN chief Antonio Guterres, a binding UN treaty to protect biodiversity in two-thirds of the Earth’s oceans “entered into force”.

What does the treaty mean and do?

The High Seas Treaty – formally known as the “biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction”, or “BBNJ” agreement – obliges countries to act in the “common heritage of humankind”, setting aside self-interest to protect biodiversity in international waters. (See Carbon Brief’s in-depth explainer on what the treaty means for climate change).

Agreed in 2023, it requires states to undertake rigorous impact assessments to rein in pollution and share benefits from marine genetic resources with coastal communities and countries. States can also propose marine protected areas to help the ocean – and life within it – become more resilient to “stressors”, such as climate change and ocean acidification.

“It’s a beacon of hope in a very dark place,” Dr Siva Thambisetty, an intellectual property expert at the London School of Economics and an adviser to developing countries at UN environmental negotiations, told Carbon Brief.

Who has signed the agreement?

Buoyed by a wave of commitments at last year’s UN Oceans conference in France, the High Seas treaty has been signed by 145 states, with 84 nations ratifying it into domestic law.

“The speed at which [BBNJ] went from treaty adoption to entering into force is remarkable for an agreement of its scope and impact,” said Nichola Clark, from the NGO Pew Trusts, when ratification crossed the 60-country threshold for it to enter into force last September.

For a legally binding treaty, two years to enter into force is quick. The 1997 Kyoto Protocol – which the US rejected in 2001 – took eight years.

While many operative parts of the BBNJ underline respect for “national sovereignty”, experts say it applies to an area outside national borders, giving territorial states a reason to get on board, even if it has implications for the rest of the oceans.

What is US involvement with the treaty?

The US is not a party to the BBNJ’s parent Law of the Sea, or a member of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) overseeing deep-sea mining.

This has meant that it cannot bid for permits to scour the ocean floor for critical minerals. China and Russia still lead the world in the number of deep-sea exploration contracts. (See Carbon Brief’s explainer on deep-sea mining).

In April 2025, the Biden administration issued an executive order to “unleash America’s offshore critical minerals and resources”, drawing a warning from the ISA.

This Tuesday, the Trump administration published a new rule to “fast-track deep-sea mining” outside its territorial waters without “environmental oversight”, reported Agence France-Presse.

Prof Lavanya Rajamani, an expert in international environmental law at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief that, while dealing with US unilateralism and “self-interest” is not new to the environmental movement, the way “in which they’re pursuing that self-interest – this time on their own, without any legal justification” has changed. She continued:

“We have to see this not as a remaking of international law, but as a flagrant breach of international law.”

While this is a “testing moment”, Rajamani believes that other states contending with a “powerful, idiosyncratic and unpredictable actor” are not “giving up on decades of multilateralism…they just asking how they might address this moment without fundamentally destabilising” the international legal order.

What next for the treaty?

Last Friday, China announced its bid to host the BBNJ treaty’s secretariat in Xiamen – “a coastal hub that sits on the Taiwan Strait”, reported the South China Morning Post.

China and Brussels currently vie as the strongest contenders for the seat of global ocean governance, given that Chile made its hosting offer days before the country elected a far-right president.

To Thambisetty, preparatory BBNJ meetings in March can serve as an important “pocket of sanity” in a turbulent world. She concluded:

“The rest of us have to find a way to navigate the international order. We have to work towards better times.”

Watch, read, listen

OWN GOAL: For Backchannel, Zimbabwean climate campaigner Trust Chikodzo called for Total Energies to end its “image laundering” at the Africa Cup of Nations.

MATERIAL WORLD: In a book review for the Baffler, Thea Riofrancos followed the “unexpected genealogy” of the “energy transition” outlined in Jean-Baptiste Fressoz’s More and More and More: An All-Consuming History.

REALTY BITES: Inside Climate News profiled Californian climate policy expert Neil Matouka, who built a plugin to display climate risk data that real-estate site Zillow removed from home listings.

Coming up

- 26 January: International day of clean energy

- 27 January: India-EU summit, New Delhi

- 31 January: Submit inputs on food systems and climate change for a report by the UN special rapporteur on climate change

- 1 February: Costa Rica elections

Pick of the jobs

- British Antarctic Survey, boating officer | Salary: £31,183. Location: UK and Antarctica

- National Centre for Climate Research at the Danish Meteorological Institute, climate science leader | Salary: NA. Location: Copenhagen, with possible travel to Skrydstrup, Karup and Nuuk

- Mongabay, journalism fellows | Stipend: $500 per month for 6 months. Location: Remote

- Climate Change Committee, carbon budgets analyst | Salary: £47,007-£51,642. Location: London

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 23 January 2026: Trump’s Davos tirade; EU wind and solar milestone; High seas hope appeared first on Carbon Brief.

DeBriefed 23 January 2026: Trump’s Davos tirade; EU wind and solar milestone; High seas hope

Greenhouse Gases

Q&A: What UK’s ‘warm homes plan’ means for climate change and energy bills

The UK government has released its long-awaited “warm homes plan”, detailing support to help people install electric heat pumps, rooftop solar panels and insulation in their homes.

It says up to 5m households could benefit from £15bn of grants and loans earmarked by the government for these upgrades by 2030.

Electrified heating and energy-efficient homes are vital for the UK’s net-zero goals, but the plan also stresses that these measures will cut people’s bills by “hundreds of pounds” a year.

The plan shifts efforts to tackle fuel poverty away from a “fabric-first” approach that starts with insulation, towards the use of electric technologies to lower bills and emissions.

Much of the funding will support people buying heat pumps, but the government has still significantly scaled back its expectations for heat-pump installations in the coming years.

Beyond new funding, there are also new efficiency standards for landlords that could result in nearly 3m rental properties being upgraded over the next four years.

In addition, the government has set out its ambition for scaling up “heat networks”, where many homes and offices are served by communal heating systems.

Carbon Brief has identified the key policies laid out in the warm homes plan, as well as what they mean for the UK’s climate targets and energy bills.

- Why do homes matter for UK climate goals?

- What is the warm homes plan?

- What is included in the warm homes plan?

- What does the warm homes plan mean for energy bills?

- What has been the reaction to the plan?

Why do homes matter for UK climate goals?

Buildings are the second-largest source of emissions in the UK, after transport. This is largely due to the gas boilers that keep around 85% of UK homes warm.

Residential buildings produced 52.8m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2024, around 14% of the nation’s total, according to the latest government figures.

Fossil-fuel heating is by far the largest contributor to building emissions. There are roughly 24m gas boilers and 1.4m oil boilers on the island of Great Britain, according to the National Energy System Operator (NESO).

This has left the UK particularly exposed – along with its gas-reliant power system – to the impact of the global energy crisis, which caused gas prices – and energy bills – to soar.

At the same time, the UK’s old housing stock is often described as among the least energy efficient in Europe. A third of UK households live in “poorly insulated homes” and cannot afford to make improvements, according to University College London research.

This situation leads to more energy being wasted, meaning higher bills and more emissions.

Given their contribution to UK emissions, buildings are “expected to be central” in the nation’s near-term climate goals, delivering 20% of the cuts required to achieve the UK’s 2030 target, according to government adviser the Climate Change Committee (CCC).

(Residential buildings account for roughly 70% of the emissions in the buildings sector, with the rest coming from commercial and public-sector buildings.)

Over recent years, Conservative and Labour governments have announced various measures to cut emissions from homes, including schemes to support people buying electric heat pumps and retrofitting their homes.

However, implementation has been slow. While heat-pump installations have increased, they are not on track to meet the target set by the previous government of 600,000 a year by 2028.

Meanwhile, successive schemes to help households install loft and wall insulation have been launched and then abandoned, meaning installation rates have been slow.

At the same time, the main government-backed scheme designed to lift homes out of fuel poverty, the “energy company obligation” (ECO), has been mired in controversy over low standards, botched installations and – according to a parliamentary inquiry – even fraud.

(The government announced at the latest budget that it was scrapping ECO.)

The CCC noted in its most recent progress report to parliament that “falling behind on buildings decarbonisation will have severe implications for longer-term decarbonisation”.

What is the warm homes plan?

The warm homes plan was part of the Labour party’s election-winning manifesto in 2024, sold at the time as a way to “cut bills for families” through insulation, solar and heat pumps, while creating “tens of thousands of good jobs” and lifting “millions out of fuel poverty”.

It replaces ECO, introduces new support for clean technologies and wraps together various other ongoing policies, such as the “boiler upgrade scheme” (BUS) grants for heat pumps.

The warm homes plan was officially announced by the government in November 2024, stating that up to 300,000 households would benefit from home upgrades in the coming year. However, the plan itself was repeatedly delayed.

In the spending review in June 2025, the government confirmed the £13.2bn in funding for the scheme pledged in the Labour manifesto, covering spending between 2025-26 and 2029-30.

The government said this investment would help cut bills by up to £600 per household through efficiency measures and clean technologies such as heat pumps, solar panels and batteries.

After scrapping ECO at the 2025 budget, the treasury earmarked an extra £1.5bn of funding for the warm homes plan over five years. This is less than the £1bn annual budget for ECO, which was funded via energy bills, but is expected to have lower administrative overheads.

In the foreword to the new plan, secretary of state Ed Miliband says that it will deliver the “biggest public investment in home upgrades in British history”. He adds:

“The warm homes plan [will]…cut bills, tackle fuel poverty, create good jobs and get us off the rollercoaster of international fossil fuel markets.”

Miliband argues in his foreword that the plan will “spread the benefits” of technologies such as solar to households that would otherwise be unable to afford them. He writes: “This historic investment will help millions seize the benefits of electrification.” Miliband concludes:

“This is a landmark plan to make the British people better off, secure our energy independence and tackle the climate crisis.”

What is included in the warm homes plan?

The warm homes plan sets out £15bn of investment over the course of the current parliament to drive uptake of low-carbon technologies and upgrade “up to” 5m homes.

A key focus of the plan is energy security and cost savings for UK households.

The government says its plan will “prioritise” investment in electrification measures, such as heat pumps, solar panels and battery storage. This is where most of the funding is targeted.

However, it also includes new energy-efficiency standards to encourage landlords to improve conditions for renters.

Some policies were notable due to their absence, such as the lack of a target to end gas boiler sales. The plan also states that, while it will consult on the use of hydrogen in heating homes, this is “not yet a proven technology” and therefore any future role would be “limited”.

New funding

Technologies such as heat pumps and rooftop solar panels are essential for the UK to achieve its net-zero goals, but they carry significant up-front costs for households. Plans for expanding their uptake therefore rely on government support.

Following the end of ECO in March, the warm homes plan will help fill the gap in funding for energy-efficiency measures that it is expected to leave.

As the chart below shows, a range of new measures under the warm homes plan – including a mix of grants and loans – as well as more funding for existing schemes, leads to an increase in support out to 2030.

One third of the total funding – £5bn in total – is aimed at low-income households, including social housing tenants. This money will be delivered in the form of grants that could cover the full cost of upgrades.

The plan highlights solar panels, batteries and “cost-effective insulation” for the least energy-efficient homes as priority measures for this funding, with a view to lowering bills.

There is also £2.7bn for the existing boiler upgrade scheme, which will see its annual allocation increase gradually from £295m in 2025-26 to £709m in 2029-30.

This is the government’s measure to encourage better-off “able to pay” households to buy heat pumps, with grants of £7,500 towards the cost of replacing a gas or oil-fired boiler. For the first time, there will also be new £2,500 grants from the scheme for air-to-air heat pumps (See: Heat pumps.)

A key new measure in the plan is £2bn for low- and zero-interest consumer loans, to help with the cost of various home upgrades, including solar panels, batteries and heat pumps.

Previous efforts to support home upgrades with loans have not been successful. However, innovation agency Nesta says the government’s new scheme could play a central role, with the potential for households buying heat pumps to save hundreds of pounds a year, compared to purchases made using regular loans.

The remaining funding over the next four years includes money assigned to heat networks and devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, which are responsible for their own plans to tackle fuel poverty and household emissions.

Heat pumps

Heat pumps are described in the plan as the “best and cheapest form of electrified heating for the majority of our homes”.

The government’s goal is for heat pumps to “increasingly become the desirable and natural choice” for those replacing old boilers. At the same time, it says that new home standards will ensure that new-build homes have low-carbon heating systems installed by default.

Despite this, the warm homes plan scales back the previous government’s target for heat-pump installations in the coming years, reflecting the relatively slow increase in heat-pump sales. It also does not include a set date to end the sale of gas boilers.

The plan’s central target is for 450,000 heat pumps to be installed annually by 2030, including 200,000 in new-build homes and 250,000 in existing homes.

This is significantly lower than the previous target – originally set in 2021 under Boris Johnson’s Conservative government – to install 600,000 heat pumps annually by 2028.

Meeting that target would have meant installations increasing seven-fold in just four years, between 2024 and 2028. Now, installations only need to increase five-fold in six years.

As the chart below shows, the new target is also considerably lower than the heat-pump installation rate set out in the CCC’s central net-zero pathway. That involved 450,000 installations in existing homes alone by 2030 – excluding new-build properties.

Some experts and campaigners questioned how the UK would remain on track for its legally binding climate goals given this scaled-back rate of heat-pump installations.

Additionally, Adam Bell, policy director at the thinktank Stonehaven, writes on LinkedIn that the “headline numbers for heat pump installs do not stack up”.

Heat pumps in existing homes are set to be supported primarily via the boiler upgrade scheme and – according to Bell – there is not enough funding for the 250,000 installations that are planned, despite an increased budget.

The government’s plan relies in part on the up-front costs of heat pump installation “fall[ing] significantly”. According to Bell, it may be that the government will reduce the size of boiler upgrade scheme grants in the future, hoping that costs will fall sufficiently.

Alternatively, the government may rely on driving uptake through its planned low-cost loans and the clean heat market mechanism, which requires heating-system suppliers to sell a growing share of heat pumps.

Rooftop solar

Rooftop solar panels are highlighted in the plan as “central to cutting energy bills”, by allowing households to generate their own electricity to power their homes and sell it back to the grid.

At the same time, rooftop solar is expected to make a “significant contribution” to the government’s target of hitting 45-47 gigawatts (GW) of solar capacity by 2030.

As it stands, there is roughly 5.2GW of solar capacity on residential rooftops.

Taken together, the government says the grants and loans set out in the warm homes plan could triple the number of homes with rooftop solar from 1.6m to 4.6m by 2030.

It says that this is “in addition” to homes that decide to install rooftop solar independently.

Efficiency standards

The warm homes plan says that the government will publish its “future homes standard” for new-build properties, alongside necessary regulations, in the first quarter of 2026.

On the same day, the government also published its intention to reform “energy performance certificates” (EPCs), the ratings that are supposed to inform prospective buyers and renters about how much their new homes will cost to keep warm.

The current approach to measuring performance for EPCs is “unreliable” and thought to inadvertently discourage heat pumps. It has faced long-standing calls for reform.

As well as funding low-carbon technologies, the warm homes plan says it is “standing up for renters” with new energy-efficiency standards for privately and socially rented homes.

Currently, private renters – who rely on landlords to invest in home improvements – are the most likely to experience fuel poverty and to live in cold, damp homes.

Landlords will now need to upgrade their properties to meet EPC ratings B and C across two new-style EPC metrics by October 2030. There are “reasonable exemptions” to this rule that will limit the amount landlords have to spend per property to £10,000.

In total, the government expects “up to” 1.6m homes in the private-rental sector to benefit from these improvements and “up to” 1.3m social-rent homes.

These new efficiency standards therefore cover three-fifths of the “up to” 5m homes helped by the plan.

The government also published a separate fuel poverty strategy for England.

Heat networks

The warm homes plan sets out a new target to more than double the amount of heating provided using low-carbon heat networks – up to 7% of England’s heating demand by 2035 and a fifth by 2050.

This involves an injection of £1.1bn for heat networks, including £195m per year out to 2030 via the green heat network fund, as well as “mobilising” the National Wealth Fund.

The plan explains that this will primarily benefit urban centres, noting that heat networks are “well suited” to serving large, multi-occupancy buildings and those with limited space.

Alongside the plan, the government published a series of technical standards for heat networks, including for consumer protection.

What does the warm homes plan mean for energy bills?

The warm homes plan could save households “hundreds on energy bills” for those whose homes are upgraded, according to the UK government.

This is in addition to two changes announced in the budget in 2025, which are expected to cut energy bills for all homes by an average of £150 a year.

This included the decisions to bring ECO to an end when the current programme of work wraps up at the end of the financial year and for the treasury to cover three-quarters of the cost of the “renewables obligation” (RO) for three years from April 2026.

Beyond this, households that take advantage of the measures outlined in the plan can expect their energy bills to fall by varying amounts, the government says.

The warm homes plan includes a number of case studies that detail how upgrades could impact energy bills for a range of households. For example, it notes that a social-rented two-bedroom semi-detached home that got insulation and solar panels could save £350 annually.

An owner-occupier three-bedroom home could save £450 annually if it gets solar panels and a battery through consumer loans offered under the warm homes plan, it adds.

Similar analysis published by Nesta says that a typical household that invests in home upgrades under the plan could save £1,000 a year on its energy bill.

It finds that a household with a heat pump, solar panels and a battery, which uses a solar and “time of use tariff”, could see its annual energy bill fall by as much as £1,000 compared with continuing to use a gas boiler, from around £1,670 per year to £670, as shown in the chart below.

Ahead of the plan being published, there were rumours of further “rebalancing” energy bills to bring down the cost of electricity relative to gas. However, this idea failed to come to fruition in the warm homes plan.

This would have involved reducing or removing some or all of the policy costs currently funded via electricity bills, by shifting them onto gas bills or into general taxation.

This would have made it relatively cheaper to use electric technologies such as heat pumps, acting as a further incentive to adopt them.

Nesta highlights that in the absence of further action with regard to policy costs, the electricity-to-gas price ratio is likely to stay at around 4.1 from April 2026.

What has been the reaction to the plan?

Many of the commitments in the warm homes plan were welcomed by a broad range of energy industry experts, union representatives and thinktanks.

Greg Jackson, the founder of Octopus Energy, described it as a “really important step forward”, adding:

“Electrifying homes is the best way to cut bills for good and escape the yoyo of fossil fuel costs.”

Dhara Vyas, chief executive of the trade body Energy UK, said the government’s commitment to spend £15bn on upgrading home heating was “substantial” and would “provide certainty to investors and businesses in the energy market”.

On LinkedIn, Camilla Born, head of the campaign group Electrify Britain, said the plan was a “good step towards backing electrification as the future of Britain, but it must go hand in hand with bringing down the costs of electricity”.

However, right-leaning publications and politicians were critical of the plan, focusing on how a proportion of solar panels sold in the UK are manufactured in China.

According to BBC News, two-thirds (68%) of the solar panels imported to the UK came from China in 2024.

In an analysis of the plan, the Guardian’s environment editor Fiona Harvey and energy correspondent Jillian Ambrose argued that the strategy is “all carrot and no stick”, given that the “longstanding proposal” to ban the installation of gas boilers beyond 2035 has been “quietly dropped”.

Christopher Hammond, chief executive of UK100, a cross-party network of more than 120 local authorities, welcomed the plan, but urged the government to extend it to include public buildings.

The government’s £3.5bn public sector decarbonisation scheme, which aimed to electrify schools, hospitals and council buildings, ended in June 2025 and no replacement has been announced, according to the network.

The post Q&A: What UK’s ‘warm homes plan’ means for climate change and energy bills appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: What UK’s ‘warm homes plan’ means for climate change and energy bills

Greenhouse Gases

China Briefing 22 January 2026: 2026 priorities; EV agreement; How China uses gas

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.

China Briefing handpicks and explains the most important climate and energy stories from China over the past fortnight. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Tasks for 2026

‘GREEN RESOLVE’: The Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) said at its annual national conference that it is “essential” to “maintain strategic resolve” on building a “beautiful China”, reported energy news outlet BJX News. Officials called for “accelerating green transformation” and “strengthening driving forces” for the low-carbon transition in 2026, it added. The meeting also underscored the need for “continued reduction in total emissions of major pollutants”, it said, as well as for “advancing source control through carbon peaking and a low-carbon transition”. The MEE listed seven key tasks for 2026 at the meeting, said business news outlet 21st Century Business Herald, including promoting development of “green productive forces”, focusing on “regional strategies” to build “green development hubs” and “actively responding” to climate change.

CARBON ‘PRESSURE’: China’s carbon emissions reduction strategy will move from the “preparatory stages” into a phase of “substantive” efforts in 2026, reported Shanghai-based news outlet the Paper, with local governments beginning to “feel the pressure” due to facing “formal carbon assessments for the first time” this year. Business news outlet 36Kr said that an “increasing number of industry participants” will have to begin finalising decarbonisation plans this year. The entry into force of the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism means China’s steelmakers will face a “critical test of cost, data and compliance”, reported finance news outlet Caixin. Carbon Brief asked several experts, including the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Li Shuo, what energy and climate developments they will be watching in 2026.

COAL DECLINE: New data released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) showed China’s “mostly coal-based thermal power generation fell in 2025” for the first time in a decade, reported Reuters, to 6,290 terawatt-hours (TWh). The data confirmed earlier analysis for Carbon Brief that “coal power generation fell in both China and India in 2025”, marking the first simultaneous drop in 50 years. Energy news outlet International Energy Net noted that wind generation rose 10% to 1,053TWh and solar by 24% to 1,573TWh.

EV agreement reached

‘NORMALISED COMPETITION’?: The EU will remove tariffs on imports of electric vehicles (EV) made in China if the manufacturers follow “guidelines on minimum pricing” issued by the bloc, reported the Associated Press. China’s commerce ministry stated that the new guidelines will “enable Chinese exporters to address the EU’s anti-subsidy case concerning Chinese EVs in a way that is more practical, targeted and consistent with [World Trade Organization] rules”, according to the state-run China Daily. An editorial by the state-supporting Global Times argued that the agreement symbolised a “new phase” in China-EU economic and trade relations in which “normalised competition” is stabilised by a “solid cooperative foundation”.

SOLAR REBATES: China will “eliminate” export rebates for solar products from April 2026 and phase rebates for batteries out by 2027, said Caixin. Solar news outlet Solar Headlines said that the removal of rebates would “directly test” solar companies’ profitability and “fundamentally reshape the entire industry’s growth logic”. Meanwhile, China imposed anti-dumping duties on imports of “solar-grade polysilicon” from the US and Korea, said state news agency Xinhua.

OVERCAPACITY MEETINGS: The Chinese government “warned several producers of polysilicon…about monopoly risks” and cautioned them not to “coordinate on production capacity, sales volume and prices”, said Bloomberg. Reuters and China Daily covered similar government meetings on “mitigat[ing] risks of overcapacity” with the battery and EV industries, respectively. A widely republished article in the state-run Economic Daily said that to counter overcapacity, companies would need to reverse their “misaligned development logic” and shift from competing on “price and scale” to competing on “technology”.

High prices undermined home coal-to-gas heating policy

SWITCHING SHOCK: A video commentary by Xinhua reporter Liu Chang covered “reports of soaring [home] heating costs following coal-to-gas switching [policies] in some rural areas of north China”. Liu added that switching from coal to gas “must lead not only to blue skies, but also to warmth”. Bloomberg said that the “issue isn’t a lack of gas”, but the “result of a complex series of factors including price regulations, global energy shocks and strained local finances”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “China Briefing” email newsletter. All you need to know about the latest developments relating to China and climate change. Sent to your inbox every Thursday.

HEATED DEBATE: Discussions of the story in China became a “domestically resonant – and politically awkward – debate”, noted the current affairs newsletter Pekingnology. It translated a report by Chinese outlet Economic Observer that many villagers in Hebei struggled with no access to affordable heating, with some turning back to coal. “Local authorities are steadily advancing energy supply,” People’s Daily said of the issue, noting that gas is “increasingly becoming a vital heating energy source” as part of China’s energy transition. Another People’s Daily article quoted one villager saying: “Coal-to-gas conversion is a beneficial initiative for both the nation and its people…Yet the heating costs are simply too high.”

DEJA-VU: This is not the first time coal-to-gas switching has encountered challenges, according to research by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, with nearby Shanxi province experiencing a similar situation. In Shanxi, a “lack of planning, poor coordination and hasty implementation” led to demand outstripping supply, while some households had their coal-based heating systems removed with no replacement secured. Others were “deterred” from using gas-based systems due to higher prices, it said.

More China news

- LOFTY WORDS: At Davos, vice-premier He Lifeng reaffirmed commitments to China’s “dual-carbon” goals and called for greater “global cooperation on climate change”, reported Caixin.

- NOT LOOKING: US president Donald Trump, also at Davos, said he was not “able to find any windfarms in China”, adding China sells them to “stupid” consumers, reported Euronews. China installed wind capacity has ranked first globally “for 15 years consecutively”, said a government official, according to CGTN.

- ‘GREEN’ FACTORIES: China issued “new guidelines to promote green [industrial] microgrids” including targets for on-site renewable use, said Xinhua. The country “pledged to advance zero-carbon factory development” from 2026, said another Xinhua report.

- JET-FUEL MERGER: A merger of oil giant Sinopec with the country’s main jet-fuel producer could “aid the aviation industry’s carbon reduction goals”, reported Yicai Global. However, Caixin noted that the move could “stifl[e] innovation” in the sustainable air fuel sector.

- NEW TARGETS: Chinese government investment funds will now be evaluated on the “annual carbon reduction rates” achieved by the enterprises or projects they support, reported BJX News.

- HOLIDAY CATCH-UP: Since the previous edition of China Briefing in December, Beijing released policies on provincial greenhouse gas inventories, the “two new” programme, clean coal benchmarks, corporate climate reporting, “green consumption” and hydrogen carbon credits. The National Energy Administration also held its annual work conference.

Spotlight

Why gas plays a minimal role in China’s climate strategy

While gas is seen in some countries as an important “bridging” fuel to move away from coal use, rapid electrification, uncompetitiveness and supply concerns have suppressed its share in China’s energy mix.

Carbon Brief explores the current role of gas in China and how this could change in the future. The full article is available on Carbon Brief’s website.

The current share of gas in China’s primary energy demand is small, at around 8-9%.

It also comprises 7% of China’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fuel combustion, adding 755m tonnes of CO2 in 2023 – twice the total CO2 emissions of the UK.

Gas consumption is continuing to grow in line with an overall uptick in total energy demand, but has slowed slightly from the 9% average annual rise in gas demand over the past decade – during which time consumption more than doubled.

The state-run oil and gas company China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) forecast in 2025 that demand growth for the year may slow further to just over 6%.

Chinese government officials frequently note that China is “rich in coal” and “short of gas”. Concerns of import dependence underpin China’s focus on coal for energy security.

However, Beijing sees electrification as a “clear energy security strategy” to both decarbonise and “reduce exposure to global fossil fuel markets”, said Michal Meidan, China energy research programme head at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

A dim future?

Beijing initially aimed for gas to displace coal as part of a broader policy to tackle air pollution.

Its “blue-sky campaign” helped to accelerate gas use in the industrial and residential sectors. Several cities were mandated to curtail coal usage and switch to gas.

(January 2026 saw widespread reports of households choosing not to use gas heating installed during this campaign despite freezing temperatures, due to high prices.)

Industry remains the largest gas user in China, with “city gas” second. Power generation is a distant third.

The share of gas in power generation remains at 4%, while wind and solar’s share has soared to 22%, Yu Aiqun, research analyst at the thinktank Global Energy Monitor, told Carbon Brief. She added:

“With the rapid expansion of renewables and ongoing geopolitical uncertainties, I don’t foresee a bright future for gas power.”

However, gas capacity may still rise from 150 gigawatts (GW) in 2025 to 200GW by 2030. A government report noted that gas will continue to play a “critical role” in “peak shaving”.

But China’s current gas storage capacity is “insufficient”, according to CNPC, limiting its ability to meet peak-shaving demand.

Transport and industry

Gas instead may play a bigger role in the displacement of diesel in the transport sector, due to the higher cost competitiveness of LNG – particularly for trucking.

CNPC forecast that LNG displaced around 28-30m tonnes of diesel in the trucking sector in 2025, accounting for 15% of total diesel demand in China.

However, gas is not necessarily a better option for heavy-duty, long-haul transportation, due to poorer fuel efficiency compared with electric vehicles.

In fact, “new-energy vehicles” are displacing both LNG-fueled trucks and diesel heavy-duty vehicles (HDVs).

Meanwhile, gas could play a “more significant” role in industrial decarbonisation, Meidan told Carbon Brief, if prices fall substantially.

Growth in gas demand has been decelerating in some industries, but China may adopt policies more favourable to gas, she added.

An energy transition roadmap developed by a Chinese government thinktank found gas will only begin to play a greater role than coal in China by 2050 at the earliest.

Both will be significantly less important than clean-energy sources at that point.

This spotlight was written by freelance climate journalist Karen Teo for Carbon Brief.

Watch, read, listen

EV OUTLOOK: Tu Le, managing director of consultancy Sino Auto Insights, spoke on the High Capacity podcast about his outlook for China’s EV industry in 2026.

‘RUNAWAY TRAIN’: John Hopkins professor Jeremy Wallace argued in Wired that China’s strength in cleantech is due to a “runaway train of competition” that “no one – least of all [a monolithic ‘China’] – knows how to deal with”.

‘DIRTIEST AND GREENEST’: China’s energy engagement in the Belt and Road Initiative was simultaneously the “dirtiest and greenest” it has ever been in 2025, according to a new report by the Green Finance & Development Center.

INDUSTRY VOICE: Zhong Baoshen, chairman of solar manufacturer LONGi, spoke with Xinhua about how innovation, “supporting the strongest performers”, standards-setting and self-regulation could alleviate overcapacity in the industry.

$574bn

The amount of money State Grid, China’s main grid operator, plans to invest between 2026-30, according to Jiemian. The outlet adds that much of this investment will “support the development and transmission of clean energy” from large-scale clean-energy bases and hydropower plants.

New science

- The combination of long-term climate change and extremes in rainfall and heat have contributed to an increase in winter wheat yield of 1% in Xinjiang province between 1989-2023 | Climate Dynamics

- More than 70% of the “observed changes” in temperature extremes in China over 1901-2020 are “attributed to greenhouse gas forcing” | Environmental Research Letters

China Briefing is written by Anika Patel and edited by Simon Evans. Please send tips and feedback to china@carbonbrief.org

The post China Briefing 22 January 2026: 2026 priorities; EV agreement; How China uses gas appeared first on Carbon Brief.

China Briefing 22 January 2026: 2026 priorities; EV agreement; How China uses gas

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits