As global temperatures rise, extreme weather events are becoming more intense and more frequent all around the world.

Over the past two decades, the cutting-edge field of extreme weather attribution has sought to establish the role that human-caused warming has played in these events.

There are now hundreds of attribution studies, assessing extremes ranging from heatwaves in China and droughts in Madagascar through to wildfires in Brazil and extreme rainfall in South Africa.

Carbon Brief has mapped every attribution study published to date, revealing that three-quarters of the extremes analysed were made more intense or likely due to climate change.

Along with this explosion of new studies, the different types of attribution studies have evolved and expanded over the past two decades.

For example, the World Weather Attribution service was established in 2015 to provide rapid-response studies, streamlining the process of estimating the human contribution to extreme events in a matter of days.

Meanwhile, a growing community of researchers are developing the “storyline approach” to attribution that focuses more on the dynamics of the specific events being studied.

Other researchers are using weather forecasts to attribute events that have not even happened yet. And many studies are now combining these methods to get the best of all worlds in their findings.

In this detailed Q&A, Carbon Brief explores how the field of attribution science has evolved over time and explains the key methods used today.

- What are the origins of ‘extreme weather attribution’?

- What is ‘probabilistic’ attribution?

- Which weather extremes can scientists link to climate change?

- Why do scientists perform ‘rapid’ attribution studies?

- Can the impacts of extreme weather be linked to climate change?

- How do scientists attribute ‘unprecedented’ events?

- How can weather forecasts be used in attribution studies?

- What are the applications of attribution science?

- What are the next steps for attribution research?

What are the origins of ‘extreme weather attribution’?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) made its first mention of attribution in its first assessment report (pdf), published in 1990. In a section called “Attribution and the fingerprint method”, the report refers to attribution as “linking cause and effect”.

In these early days of attribution science, experts used statistical methods to search for the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change in global temperature records.

However, the 1990 report says that “it is not possible at this time to attribute all or even a large part of the observed global mean warming to the enhanced greenhouse effect on the basis of the observational data currently available”.

As the observational record lengthened and scientists refined their methods, experts became more confident about attributing global temperature rise to human-caused climate change. By the time its third assessment report was published in 2001, the IPCC could state that “detection and attribution studies consistently find evidence for an anthropogenic signal in the climate record of the last 35 to 50 years”.

Just two years later, Prof Myles Allen – professor of geosystem science at the University of Oxford – wrote a Nature commentary from his home in Oxford that would open the door for attributing extreme weather events to climate change. The article begins:

“As I write this article in January 2003, the floodwaters of the River Thames are about 30 centimetres from my kitchen door and slowly rising. On the radio, a representative of the UK Met Office has just explained that although this is the kind of phenomenon that global warming might make more frequent, it is impossible to attribute this particular event (floods in southern England) to past emissions of greenhouse gases. What is less clear is whether the attribution of specific weather events to external drivers of climate change will always be impossible in principle, or whether it is simply impossible at present, given our current state of understanding of the climate system.”

Just months after Oxford’s floodwaters began to recede, a now-infamous heatwave swept across Europe. The summer of 2003 was the hottest ever recorded for central and western Europe, with average temperatures in many countries reaching 5C higher than usual.

The unexpected heat resulted in an estimated 20,000 “excess” deaths, making the heatwave one of Europe’s deadliest on record.

In 2004, Allen and two other UK-based climate scientists produced the first formal attribution study, published in Nature, which estimated the impact of human-caused climate change on the heatwave.

To conduct the study, the authors first chose the temperature “threshold” to define their heatwave. They decided on 1.6C above the 1961-90 average, because the European summer of 2003 was the first on record to exceed this average temperature.

They then used a global climate model to simulate two worlds – one mirroring the world as it was in 2003 and the other a fictional world in which the industrial revolution never happened. In the second case, the climate is influenced solely by natural changes, such as solar energy and volcanic activity, and there is no human-caused warming.

The authors ran their models thousands of times in each scenario from 1989 to 2003. As the climate is inherently chaotic, each model “run” – individual simulations of how the climate progresses over many years – produces a slightly different progression of temperatures. This means that some runs simulated a heatwave in the summer of 2003, while others did not.

The authors counted how many times the 1.6C threshold temperature was crossed in the summer of 2003 in each model run. They then compared the likelihood of crossing the threshold temperature in the world with – and a world without – climate change.

They concluded that “it is very likely that human influence has at least doubled the risk of a heatwave exceeding this threshold magnitude”.

A Nature commentary linked to the study called the paper a “breakthrough”, stating that it was the “first successful attempt to detect man-made influence on a specific extreme climatic event”.

In the decade following the heatwave study, more teams from around the world began to use the same methods – known as “probabilistic”, “risk-based” or “unconditional” attribution.

Prof Peter Stott is a science fellow in climate attribution at the UK Met Office and an author on the study. Stott tells Carbon Brief that the basic methods used in this first attribution study are “still used to this day”, but that scientists now use more “up-to-date” climate models than the one used in his seminal study.

What is ‘probabilistic’ attribution?

As the 2004 Nature study demonstrated, probabilistic attribution involves scientists running climate models thousands of times in scenarios with and without human-caused climate change, then comparing the two.

This allows them to say how much more likely, intense or long-lasting an event was due to climate change.

Many studies since have added a third scenario, in which the planet is warmer than present-day temperatures, to assess how climate change may impact extreme weather events in the future.

The figure below shows three distributions of multiple different simulated extreme events. The x-axis (horizontal) represents the intensity of the climate variable – in this instance temperature – with lower temperatures on the left and higher temperatures on the right. The y-axis (vertical) shows the likelihood of this variable hitting certain values.

Each curve shows how the climate variable behaves in a different scenario, or “world”. The red-shaded curve shows a pre-industrial world that was not warmed by human influence, the yellow-shaded curve indicates today’s climate, while the dashed line shows a future, warmer world. The curves shift from left to right as the climate warms.

The peak of each curve shows the most likely temperatures, while likelihood is lowest at the far left and far right of each curve, where temperatures are most extreme. The hatched areas show the temperatures that cross a predefined “threshold” temperature. (In the attribution study on the 2003 European heatwave, this threshold was defined as 1.6C above the 1961-90 average.)

The three curves show how the threshold is more likely to be crossed as the world warms.

Which weather extremes can scientists link to climate change?

In 2011, the American Meteorological Society decided to include a “special supplement” about attribution research in its annual report.

The supplement presented six different attribution studies. It generated significant media interest and the “Explaining Extreme Events” report has been published by Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society almost every year since.

As the research field has grown, so too has the range of different extremes that have been studied.

Heatwaves are generally considered the simplest extreme events to attribute, because they are mainly driven by thermodynamic influences. In contrast, storms and droughts are more strongly affected by complex atmospheric dynamics, so can be trickier to simulate in a model.

The graphic below shows the relative confidence of attributing different types of extreme events.

Attribution studies on extreme heat often assess how much hotter, long-lasting or likely an event was due to climate change. For example, one study finds that the summer heatwave that hit France in 2019 was made 1.5-3C hotter due to climate change and about 100 times more likely.

Heatwaves are the most-studied extreme event in attribution literature, but are becoming “less and less interesting for researchers”, according to a Bloomberg article from 2020.

Assessing extreme rainfall is more complicated – in part because the Earth’s chaotic weather system means that the size and path of a storm or heavy rainfall event has a large element of chance, which can make it challenging to identify where climate change fits in.

Nevertheless, many teams have published studies attributing extreme rainfall events and storms. For example, one study (pdf) found that climate change doubled the likelihood of the intense rainfall that fell in northern China in September 2021.

Scientists also study more complex events, such as drought, wildfires and floods, which are impacted by factors including land use and disaster preparedness.

For example, there are many different ways to define a drought. Some are linked just to rainfall, while others consider factors including soil moisture, groundwater and river flow. Some attribution studies investigating the impact of climate change on drought focus only on rainfall deficit, while others (pdf) study temperature or vapour pressure deficit – the difference between the amount of moisture in the air and how much moisture the air can hold when it is saturated.

A scientist’s decision about which type of drought to study sometimes depends on the available data and the type of impacts caused by the drought. In other cases, the choice may come down to what caused the biggest impact on people.

For example, in late 2022, South America was plagued by a severe drought that caused widespread crop failure. An attribution study on the event, therefore, focused on “agricultural” drought, which captures the response of rainfall on soil moisture conditions and is the most relevant for crop health.

Meanwhile, a study on drought in Madagascar over 2019-21 chose to focus on rainfall deficit. The study says “this was because recent research found rainfall deficits were the primary driver of drought in regions of East Africa with very similar climatic properties to south-west Madagascar”.

Wildfires are affected by conditions including temperature, rainfall, wind speed and land use. While some wildfire attribution studies focus on vapour pressure deficit, others quantify the fire weather index, which looks at the effects of fuel moisture and wind on fire behaviour and spread”.

Tropical cyclones are also complex. There is evidence that climate change can increase the peak “rain rates” and wind speeds of tropical cyclones, and that storm tracks are shifting poleward. There are many aspects of a cyclone that can be analysed, such as rainfall intensity, storm surge height and storm size.

Why do scientists perform ‘rapid’ attribution studies?

As extreme weather attribution became more mainstream, researchers began to produce studies more quickly. However, challenges in communicating the findings of attribution studies in a timely way soon became evident.

After conducting a study, writing it up and submitting it to a journal, it can still take months or years for research to be published. This means that, by the time an attribution study is published, the extreme event has likely long passed.

The World Weather Attribution (WWA) initiative was founded in 2015 to tackle this issue. The team uses a standard, peer-reviewed methodology for their studies, but does not publish the results in formal journals – instead publishing them directly on their website.

(After publishing these “rapid attribution” studies on their website, the team often write full papers for publication in formal journals, which are then peer reviewed.)

This means that rather than taking months or years to publish their research, the team can make their findings public just days or weeks after an extreme weather event occurs.

In 2021, the founders of the initiative – including Carbon Brief contributing editor Dr Friederike Otto, who is a senior lecturer in climate science at Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute – wrote a Carbon Brief guest post explaining why they founded WWA:

“By reacting in a matter of days or weeks, we have been able to inform key audiences with a solid scientific result swiftly after an extreme event has occurred – when the interest is highest and results most relevant.”

The guest post explains that to conduct an attribution study, the WWA team first uses observed data to assess how rare the event is in the current climate – and how much this has changed over the observed record. This is communicated using a “return period” – the expected frequency an event of this magnitude could be expected under a given climate.

For example, the WWA analysed the UK’s record-shattering heatwave of 2022, when the country recorded temperatures above 40C for the first time. They found that the maximum temperature seen in the UK on 19 July 2022 has a 1,000-year return period in today’s climate – meaning that even in today’s climate, 40C heat would only be expected, on average, once in a millennium.

The authors then use climate models to carry out the “probabilistic” attribution study, to determine how much more intense, likely or long-lasting the event was as a result of climate change. They conclude by conducting “vulnerability and exposure” analysis, which often highlights other socioeconomic problems.

Sometimes, the authors conclude that climate change did not influence the event. For example, a 2021 rapid attribution study by WWA found that poverty, poor infrastructure and dependence on rain-fed agriculture were the main drivers of the ongoing food crisis in Madagascar, while climate change played “no more than a small part”.

Other groups are also conducting rapid attribution studies. For example, a group of scientists – including some WWA collaborators – recently launched a “rapid experimental framework” research project called ClimaMeter. The tool provides initial attribution results just hours after an extreme weather event takes place.

ClimaMeter focuses on the atmospheric circulation patterns that cause an extreme event – for example, a low-pressure system in a particular region. Once an event is defined, the scientists search the historical record to find events with similar circulation patterns to calculate how the intensity of the events has changed over time.

Can the impacts of extreme weather be linked to climate change?

A branch of attribution science called “impact attribution” – which aims to quantify the social, economic and/or ecological impacts of climate change on extreme weather events – is also gaining popularity. There are four main types of impact attribution, as shown in the graphic below.

1) Trend-to-trend impact attribution

The first method, called “trend-to-trend” impact attribution, assesses long-term trends in both the climate system and in “health outcomes”. This approach was used in a 2021 study on heat-related mortality around the world, which received extensive media attention.

The authors used data from 732 locations in 43 countries to identify relationships between temperature and mortality in different locations, known as “exposure-response functions”. This allowed them to estimate how many people would die in a given location, if temperatures reach a certain level.

The authors used these relationships to calculate heat-related mortality over 1991-2018 for each location under two scenarios – one with and one without human-caused climate change. The study concluded that 37% of “warm-season heat-related deaths” can be attributed to human-caused climate change.

2) Event-to-event attribution

The second type of study is known as “event-to-event” attribution. In one study using this method, the authors used data on observed mortality rates to determine how many people died in Switzerland during the unusually warm summer of 2022.

They calculated how much climate change contributed to warming during that summer. They then then ran a model to calculate the “hypothetical heat-related burden” that would have been seen during the summer without the warming influence of climate change.

Using this method, they estimate that 60% of the 623 heat-related deaths “could have been avoided in absence of human-induced climate change”.

3) Risk-based event attribution

“Risk-based” event impact attribution – which is demonstrated in a more recent study on the 2003 European heatwave – is the third type of impact attribution. This method combines probabilistic event attribution with resulting health outcomes.

When the paper was published, its lead author, Prof Dann Mitchell – a professor of climate science at the University of Bristol – explained the method to Carbon Brief:

“We have a statistical relationship between the number of additional deaths per degree of warming. This is specific to a certain city and changes a lot between cities. We use climate simulations to calculate the heat in 2003, and in 2003 without human influences. Then we compare the simulations, along with the observations.”

They find, for example, that in the summer of 2003, anthropogenic climate change increased the risk of heat-related mortality in London by around 20%. This means that out of the estimated 315 deaths in London during the heatwave, 64 were due to climate change.

4) Fractional attribution

In the final method, known as “fractional” attribution, the authors combine the results of two independent numbers – an estimation of the total damages caused by an extreme weather event, and a calculation of the proportion of the risk from an extreme weather event for which anthropogenic climate change is responsible, known as the “fraction of attributable risk” (FAR).

The authors of one study used this method to estimate the economic damages linked to Hurricane Harvey.

The authors calculate that “fraction of attributable risk” for the rainfall from Harvey was around three-quarters – meaning that climate change was responsible for three-quarters of the intense rainfall.

Separately, the authors find that according to best estimates, the hurricane caused damages of around US$90bn. From this, the authors conclude that US$67bn of the damages caused by the Hurricane’s intense rainfall can be attributed to climate change.

A study on the 2010 Russian heatwave also used this method. The authors found that the heatwave was responsible for more than 55,000 deaths (pdf), and found an 80% chance that the extreme heat would not have occurred without climate warming. The study concludes that almost 45,000 of the deaths were attributable to human-caused climate change.

However, the fractional attribution method has received criticism. One paper argues that the method “inflates the impacts associated with anthropogenic climate change”, because it “incorrectly assumes” that the event has no impact unless it exceeds the threshold defined by the researchers.

Some of the authors of the Hurricane Harvey paper later wrote a paper advising caution in interpreting the results of FAR studies. They say:

“The fraction of attributable risk (FAR) method, useful in extreme weather attribution research, has a very specific interpretation concerning a class of events, and there is potential to misinterpret results from weather event analyses as being applicable to specific events and their impact outcomes…FAR is not generally appropriate when estimating the magnitude of the anthropogenic signal behind a specific impact.”

Expanding scope

Impact attribution is continuing to expand in scope. For example, studies are now being conducted to assess the impact of climate change on disease transmission.

In 2020, scientists quantified the influence of climate change on specific episodes of extreme ice loss from glaciers for the first time. They found that human-caused climate change made the extreme “mass loss” seen in glaciers in the Southern Alps, New Zealand, in 2018 at least 10 times more likely.

Scientists have also linked climate change to ecosystem shifts. One study focusing on temperature finds that the “extremely early cherry tree flowering” seen in Kyoto in 2021 was made 15 times more likely due to climate change.

Others go even further, linking weather extremes to societal impacts. For example, a 2021 study published in Scientific Reports says:

“By combining an extreme event attribution analysis with a probabilistic model of food production and prices, we find that climate change increased the likelihood of the 2007 co-occurring drought in South Africa and Lesotho, aggravating the food crisis in Lesotho.”

Meanwhile, Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute is working on an initiative to publish rapid impact attribution studies about extreme weather events around the world. Similar to WWA studies, these rapid studies will not be peer reviewed individually, but will be based on a peer-reviewed methodology.

Dr Emily Theokritoff – a research associate at Grantham, who is working on the initiative, tells Carbon Brief that it will be launched “in the near future”. She adds:

“The aim is to recharge the field, start a conversation about climate losses and damages, and help people understand how climate change is making life more dangerous and more expensive.”

How do scientists attribute ‘unprecedented’ events?

An attribution method known as the “storyline approach” or “conditional attribution” has become increasingly popular over the past decade – despite initially causing controversy in the attribution community.

In this approach, researchers first select an extreme weather event, such as a specific heatwave, storm or drought. They then identify the physical components, such as sea surface temperature, soil moisture and atmospheric dynamics, that led to the event unfolding in the way it did. This series of events is called a “storyline”.

The authors then use models to simulate this “storyline” in two different worlds – one in the world as we know it and one in a counterfactual world – for example, with a different sea surface temperature or CO2 level. By comparing the model runs, the researchers can draw conclusions about how much climate change influenced that event.

The storyline approach is useful for explaining the influence of climate change on the physical processes that contributed to the event. It can also be used to explore in detail how this event would have played out in a warmer (future) or cooler (pre-industrial) climate.

One study describes the storyline approach as an “autopsy”, explaining that it “gives an account of the causes of the extreme event”.

Prof Ted Shepherd, a researcher at the University of Reading, was one of the earliest advocates of the storyline attribution approach. At the EGU general assembly in Vienna in April 2024, Shepherd provided the opening talk in a session on storyline attribution.

He told the packed conference room that the storyline approach was born out of the need for a “forensic” approach to attribution, rather than a “yes/no” approach. He emphasised that extreme weather events have “multiple causes” and that the storyline approach allows researchers to dissect each of these components.

Dr Linda van Garderen is a postdoctoral researcher at Utrecht University and has carried out multiple studies using the storyline method. She tells Carbon Brief that, while traditional attribution typically investigates probability, the storyline approach analyses intensity.

For example, she led an attribution study using the storyline method which concluded that the 2003 European and 2010 Russian heatwaves would have been 2.5-4C cooler in a world without climate change.

She adds that it can make communication easier, telling Carbon Brief that “probabilities can be challenging to interpret in practical daily life, whereas the intensity framing of storyline studies is more intuitive and can make attribution studies easier to understand”.

Dr Nicholas Leach is a researcher at the University of Oxford who has conducted multiple studies using the storyline approach. He tells Carbon Brief that probabilistic attribution often produces “false negatives”, wrongly concluding that climate change did not influence an event.

This is because climate models have “biases and uncertainties” which can lead to “noise” – particularly when it comes to dynamical features such as atmospheric circulation patterns. Probabilistic attribution methods often end up losing the signal of climate change in this noise, he explains.

The storyline approach is able to avoid these issues more easily, he says. He explains that by focusing on the dynamics of one specific event, rather than a “broad class of events”, storyline studies can eliminate some of this noise, making it more straightforward to identify a signal, he says.

Conversely, others have critiqued the storyline method for producing false positives, which wrongly claim that climate change influenced an extreme weather event.

The storyline approach has also been praised for its ability to attribute “unprecedented” events. In the EGU session on the storyline method, many presentations explored how the storyline method could be used to attribute “statistically impossible” extremes.

Leach explains that when a completely unprecedented extreme event occurs, statistical models often indicate that the event “shouldn’t have happened”. When running a probabilistic analysis using these models, Leach explains: “You end up with the present probability being zero and past probability being zero, so you can’t say a lot.”

He points to the Pacific north-west heatwave of 2021 as an example of this. This event was one of the most extreme regional heat events ever recorded globally, breaking some local high temperature records by more than 6C.

WWA conducted a rapid attribution study on the heatwave, using its probabilistic attribution method. The heatwave was “so extreme” that the observed temperatures “lie far outside the range” of historical observations, the researchers said.

Their assessment suggests that the heatwave was around a one-in-1,000-year event in today’s climate and was made at least 150-times more likely because of climate change.

Leach and his colleagues used the storyline method to attribute the same heatwave. The methods of this study will be discussed more in the following section.

Leach explains that using the storyline approach, he was able to consider the physics of the event, including an atmospheric river that coincided with the “heat dome” that was a key feature of the event. This helped him to represent the event well in his models. The study concluded that the heatwave was 1.3C hotter and eight times more likely as a result of climate change.

Many experts tell Carbon Brief there was initially tension in the attribution community between probabilistic and storyline advocates when the latter was first introduced. However, as the storyline method has become more mainstream, criticism has abated and many scientists are now publishing research using both techniques.

Van Garderen tells Carbon Brief that storyline attribution is “adding to the attribution toolbox”, rather than attempting to replace existing methods. She emphasises that probability-based and storyline attribution answer different questions, and that both are important.

How can weather forecasts be used in attribution studies?

Forecast attribution is the most recent major addition to the attribution toolbox. This method uses weather forecasts instead of climate models to carry out attribution studies. Many experts describe this method as sitting part-way between probabilistic and storyline attribution.

One benefit of using forecasts, rather than climate models, is that their higher resolution allows them to simulate extreme weather events in more detail. By using forecasts, scientists can also attribute events that have not yet happened.

The first use of “advance forecasted” attribution analysis (pdf) quantified the impact of climate change on the size, rainfall and intensity of Hurricane Florence before it made landfall in North Carolina in September 2018.

The authors, in essence, carried out the probabilistic attribution method, using two sets of short-term forecasts for the hurricane rather than large-scale climate models. The analysis received a mixed reaction. Stott told Carbon Brief at the time that it was “quite a cool idea”, but was highly dependent on being able to forecast such events reliably.

Dr Kevin Trenberth, distinguished senior scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, told Carbon Brief in 2019 that the study was “a bit of a disaster”, explaining that the quality of the forecast was questionable for the assessment.

The authors subsequently published a paper in Science Advances reviewing their study “with the benefit of hindsight”. The authors acknowledged that the results are quite a way off what they forecasted. However, they also claimed to have identified what went wrong with their forecasted analysis.

Problems with the “without climate change” model runs created a larger contrast against their real-world simulations, meaning the analysis overestimated the impact of climate change on the event, they said.

Nonetheless, the study did identify a quantifiable impact of climate change on Hurricane Florence, adding to the evidence from studies by other author groups.

This research team has since published more forecast-based attribution studies on hurricanes. One study used hindcasts – forecasts that start from the past and then run forward into the present – to analyse the 2020 hurricane season. The team then ran a series of “counterfactual” hindcasts over the same period, without the influence of human warming from sea surface temperatures.

They found that warmer waters increased three-hour rainfall rates and three-day accumulated rainfall for tropical storms by 10% and 5%, respectively, over the 2020 season.

Meanwhile, a 2021 study by a different team showed how it was possible to use traditional weather forecasts for attribution. The researchers, who penned a Carbon Brief guest post about their work, found that the European heatwave of February 2019 was 42% more likely for the British Isles and at least 100% more likely for France.

To conduct their study, the authors used a weather forecast model – also known as a “numerical weather prediction” model (NWP).

They explain that a NWP typically runs at a higher resolution than a climate model, meaning that it has more, smaller grid cells. This allows it to simulate processes that a climate model cannot and makes them “more suitable for studying the most extreme events than conventional climate models,” the authors argue.

More recently, Leach and his team carried out a forecast attribution study on the record-breaking Pacific north-west heatwave of 2021, years after the event took place.

The authors defined 29 June 2021 as the start of the event, as this is when the maximum temperature of the heatwave was recorded. They then ran their forecasts using a range of “lead times” – the number of days before the event starts that the model simulation is initialised.

The shortest lead time in this study was three days, meaning the scientists began running the model using the weather conditions recorded on 26 June 2021. The short lead time meant that they could tailor the model very closely to the weather conditions at this time and simulated the event itself very accurately.

By comparison, the longest lead times used in this study were 2-4 months. This means that the models were initialised in spring and, by the time they simulated the June heatwave, their simulation did not closely resemble the events that actually unfolded.

Leach tells Carbon Brief that by lengthening the lead time of the weather forecast, they can effectively “shift the dial” from storyline to probabilistic attribution. He explains:

“If you’re using a forecast that’s initialised really near to your event, then you’re kind of going down that storyline approach, by saying, ‘I want what my model is stimulating to look really similar to the event I’m interested in’…

“The further back [in time] you go, the closer you get to the more probabilistic style of statements that are more unconditioned.”

This combination of storyline and probabilistic attribution allows the authors to draw conclusions both about how climate change affected the intensity and the likelihood of the heatwave. The authors estimate that the heatwave was 1.3C more intense and eight times more likely as a result of climate change.

More recently, Climate Central has produced a tool that uses temperature forecasts over the US over the coming days to calculate a “climate shift index”. This index gives the ratio of how common the forecasted temperature is in today’s climate, compared to how likely it would be in a world without climate change.

The index runs from five to minus five. A result of zero indicates that climate change has no detectable influence, an index of five means that climate change made the temperature at least five times more likely and an index of minus five means that climate change made the temperature at least five times less likely.

The tool can be used for attribution. For example, recent analysis by the group used the index to quantify how climate change has influenced the number of uncomfortably hot nights. It concluded:

“Due to human-caused climate change, 2.4 billion people experienced an average of at least two additional weeks per year where nighttime temperatures exceeded 25C. Over one billion people experienced an average of at least two additional weeks per year of nights above 20C and 18C.”

What are the applications of attribution science?

One often-touted application of attribution studies is to raise awareness about the role of climate change in extreme weather events. However, there are limited studies about how effective this is.

One study presents the results of focus group interviews with UK scientists, who were not working on climate change, in which participants were given attribution statements. The study concludes:

“Extreme event attribution shows significant promise for climate change communication because of its ability to connect novel, attention-grabbing and event-specific scientific information to personal experiences and observations of extreme events.”

However, the study identified a range of challenges, including “adequately capturing nuances”, “expressing scientific uncertainty without undermining accessibility of key findings” and difficulties interpreting mathematical aspects of the results.

In another experiment, researchers informed nearly 4,000 adults in the US that climate change had made the July 2023 heatwave in the US at least five times more likely. The team also shared information from Climate Central’s climate shift index. According to the study, both approaches “increased the belief that climate change made the July 2023 heatwave more likely and is making heatwaves in general more likely as well”.

Meanwhile, as the science of extreme weather attribution becomes more established, lawyers, governments and civil society are finding more uses for this evolving field.

For example, attribution is starting to play an important role in courts. In 2017, two lawyers wrote a Carbon Brief guest post stating “we expect that attribution science will provide crucial evidence that will help courts determine liability for climate change related harm”.

Four years later, the authors of a study on “climate litigation” wrote a Carbon Brief guest post explaining how attribution science can be “translated into legal causality”. They wrote:

“Attribution can bridge the gap identified by judges between a general understanding that human-induced climate change has many negative impacts and providing concrete evidence of the role of climate change at a specific location for a specific extreme event that already has led or will lead to damages.”

In 2024, around 2,000 Swiss women used an attribution study, alongside other evidence, to win a landmark case in the European Court of Human Rights. The women, mostly in their 70s, said that their age and gender made them particularly vulnerable to heatwaves linked to climate change. The court ruled that Switzerland’s efforts to meet its emissions targets had been “woefully inadequate”.

The 2024 European Geosciences Union conference in Vienna dedicated an entire session to climate change and litigation. Prof Wim Thiery – a scientist who was involved in many conference sessions on climate change and litigation – tells Carbon Brief that attribution science is particularly important for supporting “reparation cases”, in which vulnerable countries or communities seek compensation for the damages caused by climate change.

He adds Carbon Brief that seeing the “direct and tangible impact” of an attribution study in a court case “motivates climate scientists in engaging in this community”.

(Other types of science are also important in court cases related to climate change, he added. For example, “source attribution” identifies the relative contribution of different sectors and entities – such as companies or governments – to climate change.)

Dr Rupert Stuart-Smith, a research associate in climate science and the law at the University of Oxford’s Sustainable Law Programme, adds:

“We’re seeing a new evolution whereby communities are increasingly looking at impact-relevant variables. Think about inundated areas, lake levels, heatwave mortalities. These are the new target variables of attribution science. This is a new frontier and we are seeing that those studies are directly usable in court cases.”

He tells Carbon Brief that some cases “have sought to hold high-emitting corporations – such as fossil fuel or agricultural companies – liable for the costs of climate change impacts”. He continues:

“In cases like these, claimants typically need to show that climate change is causing specific harms affecting them and courts may leverage attribution or climate projections to adjudicate these claims. Impact attribution is particularly relevant in this context.”

Dr Delta Merner is a lead scientist at the science hub for climate litigation. She tells Carbon Brief that “enhanced source attribution for companies and countries” will be “critical” for holding major emitters accountable. She adds:

“This is an urgent time for the field of attribution science, which is uniquely capable of providing robust, actionable evidence to inform decision-making and drive accountability.”

Meanwhile, many countries’s national weather services are working on “operational attribution” – the regular production of rapid attribution assessments.

Stott tells Carbon Brief that the UK Met Office is operationalising attribution studies. For example, on 2 January 2024, it announced that 2023 was the second-warmest year on record for the UK, with an average temperature of 9.97C.

New methods are also being developed. For example, groups, such as the “eXtreme events: Artificial Intelligence for Detection and Attribution” (XAIDA) team, are researching the use of machine learning and artificial intelligence for attribution studies.

One recent attribution study uses a machine-learning approach to create “dynamically consistent counterfactual versions of historical extreme events under different levels of global mean temperature”. The authors estimate that the south-central North American heatwave of 2023 was 1.18-1.42C warmer because of global warming.

The authors conclude:

“Our results broadly agree with other attribution techniques, suggesting that machine learning can be used to perform rapid, low-cost attribution of extreme events.”

Other scientists are using a method called UNSEEN, which involves running models thousands of times to increase the size of the datasets used to make it easier to derive accurate probabilities from highly variable extremes.

What are the next steps for attribution research?

The experts that Carbon Brief spoke to for this article have high hopes for the future of attribution science. For example, Stott says:

“Attribution science has great potential to improve the resilience of societies to future climate change, can help monitor progress towards the Paris goals of keeping global warming to well below 2C and can motivate progress in driving down emissions towards net-zero by the middle of this century.”

However, despite the progress made over the past two decades, there are still challenges to overcome. One of the key barriers in attribution science is a lack of high-quality observational data in low-income countries.

To carry out an attribution study, researchers need a Iong, high-quality dataset of observations from the area being studied. However, inadequate funding or political instability means that many developing countries do not have sufficient weather station data.

In a 2016 interview with Carbon Brief, Allen said that “right now there is obviously a bias towards our own backyards – north-west Europe, Australia and New Zealand.”

Many WWA studies in global-south countries mention the challenge of finding adequate data and sometimes this affects the results. A WWA study of the 2022 drought in west Africa’s Sahel region was unable to find the signal of climate change in the region’s rainfall pattern – in part, due to widespread uncertainties in the observational data.

Otto, who was an author on the study, explained at the time:

“It could either be because the data is quite poor or because we have found the wrong indices. Or it could be because there really is no climate change signal…We have no way of identifying which of these three options it is.”

Developing better observational datasets is an ongoing challenge. It is highlighted in much of the literature on attribution as an important next step for attribution science – and for climate science more widely. Merner tells Carbon Brief that scientists also need to work on developing “novel approaches for regions without baseline data”.

Meanwhile, many scientists expect the methods used in attribution science to continue evolving. The Detection and Attribution Model Intercomparison Project is currently collecting simulations, which will support improved attribution of climate change in the next set of assessment reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Mitchell says that, over the next decade, he thinks that “we will move away from the more generic attribution methods that have served us well to this point, and start developing and applying more targeted – and even more defensible – methods”.

In particular, he highlights the need for more specific methods for impact attribution – for example, studying the impacts of weather events on health outcomes, biodiversity changes or financial losses.

He continues:

“The interplay of different socioeconomic states and interventions with that of climate change can make these particularly difficult to study – but we are getting there with our more advanced, albeit computationally expensive methods, such as using weather forecast models as the foundation of our attribution statements.”

Stott tells Carbon Brief that incorporating impacts into attribution assessments is a “crucial area for development” in attribution science. He explains that impact attribution is “very relevant to the loss-and-damage agenda and further developments in attribution science are likely to include the ability to attribute the financial costs of storms”.

Stuart-Smith tells Carbon Brief that, “in the coming years, growing numbers of studies will quantify the economic burden of climate change and its effects on a broader range of health impacts, including from vector and water-borne diseases”.

Leach also tells Carbon Brief that it is “important for attribution to move their focus beyond physical studies and into quantitative impact studies to increase their relevance and utility in policy and the media”.

He adds:

“Utilising weather forecasts for attribution would fit neatly with this aim as those same models are already widely used by emergency managers and built into impact modelling frameworks.”

Similarly, Stott tells Carbon Brief that “forecast attribution shows great potential”. He explains that by “progressing that science” will allow this method to be used to attribute more types of extreme weather with greater confidence.

Leach advocates for greater use of weather forecast models for all types of attribution. He says:

“Weather forecast models have demonstrated repeatedly over the past few years that they are capable of accurately representing even unprecedented weather extremes. Using these validated state-of-the-art models for attribution could bring an increase in confidence in the results.”

Many scientists also tell Carbon Brief about the importance of operationalising attribution. The weather services in many countries already have this in place. Stott tells Carbon Brief that groups in Japan, South Korea, Australia and the US are also “at various stages of developing operational attribution services”.

Meanwhile, Otto tells Carbon Brief that “the most important next step for attribution in my view is to really integrate the assessment of vulnerability and exposure into the attribution studies”. She adds:

“In order for attribution to truly inform adaptation it is essential though to go from attributing hazards, as we do now mainly, to disentangling drivers of disasters.”

Mitchell adds that he thinks attribution statements “are absolutely essential for [countries to make] national adaptation plans”.

Meanwhile, another study suggests that extreme event attribution studies could be used by engineers, along with climate projections, to assist climate adaptation for civil infrastructure.

Leach tells Carbon Brief that attribution could be useful in the insurance sector for similar reasons. He adds that many insurance sectors use the same forecasts in their catastrophe models that climate scientists use for forecast attribution, meaning that it should be straightforward to add attribution studies into their pipelines.

The post Q&A: The evolving science of ‘extreme weather attribution’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

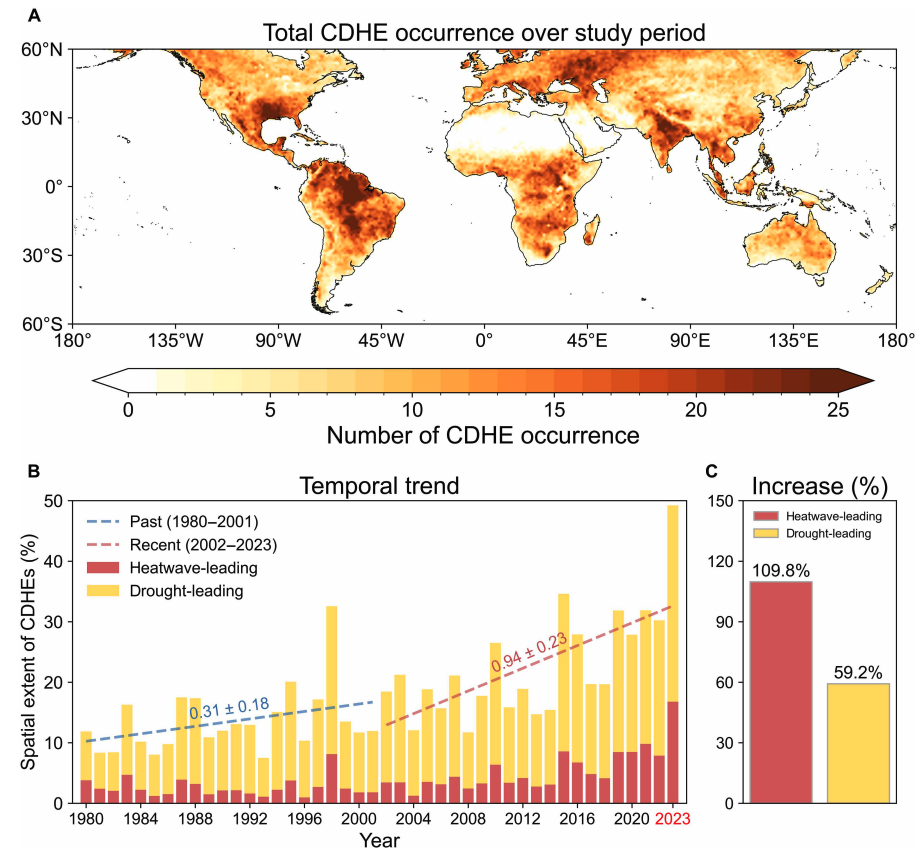

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 6 March 2026: Iran energy crisis | China climate plan | Bristol’s ‘pioneering’ wind turbine

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Energy crisis

ENERGY SPIKE: US-Israeli attacks on Iran and subsequent counterattacks across the Middle East have sent energy prices “soaring”, according to Reuters. The newswire reported that the region “accounts for just under a third of global oil production and almost a fifth of gas”. The Guardian noted that shipping traffic through the strait of Hormuz, which normally ferries 20% of the world’s oil, “all but ground to a halt”. The Financial Times reported that attacks by Iran on Middle East energy facilities – notably in Qatar – triggered the “biggest rise in gas prices since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine”.

‘RISK’ AND ‘BENEFITS’: Bloomberg reported on increases in diesel prices in Europe and the US, speculating that rising fuel costs could be “a risk for president Donald Trump”. US gas producers are “poised to benefit from the big disruption in global supply”, according to CNBC. Indian government sources told the Economic Times that Russia is prepared to “fulfil India’s energy demands”. China Daily quoted experts who said “China’s energy security remains fundamentally unshaken”, thanks to “emergency stockpiles and a wide array of import channels”.

‘ESSENTIAL’ RENEWABLES: Energy analysts said governments should cut their fossil-fuel reliance by investing in renewables, “rather than just seeking non-Gulf oil and gas suppliers”, reported Climate Home News. This message was echoed by UK business secretary Peter Kyle, who said “doubling down on renewables” was “essential” amid “regional instability”, according to the Daily Telegraph.

China’s climate plan

PEAK COAL?: China has set out its next “five-year plan” at the annual “two sessions” meeting of the National People’s Congress, including its climate strategy out to 2030, according to the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. The plan called for China to cut its carbon emissions per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) by 17% from 2026 to 2030, which “may allow for continued increase in emissions given the rate of GDP growth”, reported Reuters. The newswire added that the plan also had targets to reach peak coal in the next five years and replace 30m tonnes per year of coal with renewables.

ACTIVE YET PRUDENT: Bloomberg described the new plan as “cautious”, stating that it “frustrat[es] hopes for tighter policy that would drive the nation to peak carbon emissions well before president Xi Jinping’s 2030 deadline”. Carbon Brief has just published an in-depth analysis of the plan. China Daily reported that the strategy “highlights measures to promote the climate targets of peaking carbon dioxide emissions before 2030”, which China said it would work towards “actively yet prudently”.

Around the world

- EU RULES: The European Commission has proposed new “made in Europe” rules to support domestic low-carbon industries, “against fierce competition from China”, reported Agence France-Presse. Carbon Brief examined what it means for climate efforts.

- RECORD HEAT: The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has said there is a 50-60% chance that the El Niño weather pattern could return this year, amplifying the effect of global warming and potentially driving temperatures to “record highs”, according to Euronews.

- FLAGSHIP FUND: The African Development Bank’s “flagship clean energy fund” plans to more than double its financing to $2.5bn for African renewables over the next two years, reported the Associated Press.

- NO WITHDRAWAL: Vanuatu has defied US efforts to force the Pacific-island nation to drop a UN draft resolution calling on the world to implement a landmark International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruling on climate, according to the Guardian.

98

The number of nations that submitted their national reports on tackling nature loss to the UN on time – just half of the 196 countries that are part of the UN biodiversity treaty – according to analysis by Carbon Brief.

Latest climate research

- Sea levels are already “much higher than assumed” in most assessments of the threat posed by sea-level rise, due to “inadequate” modelling assumptions | Nature

- Accelerating human-caused global warming could see the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit crossed before 2030 | Geophysical Research Letters covered by Carbon Brief

- Future “super El Niño events” could “significantly lower” solar power generation due to a reduction in solar irradiance in key regions, such as California and east China | Communications Earth & Environment

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

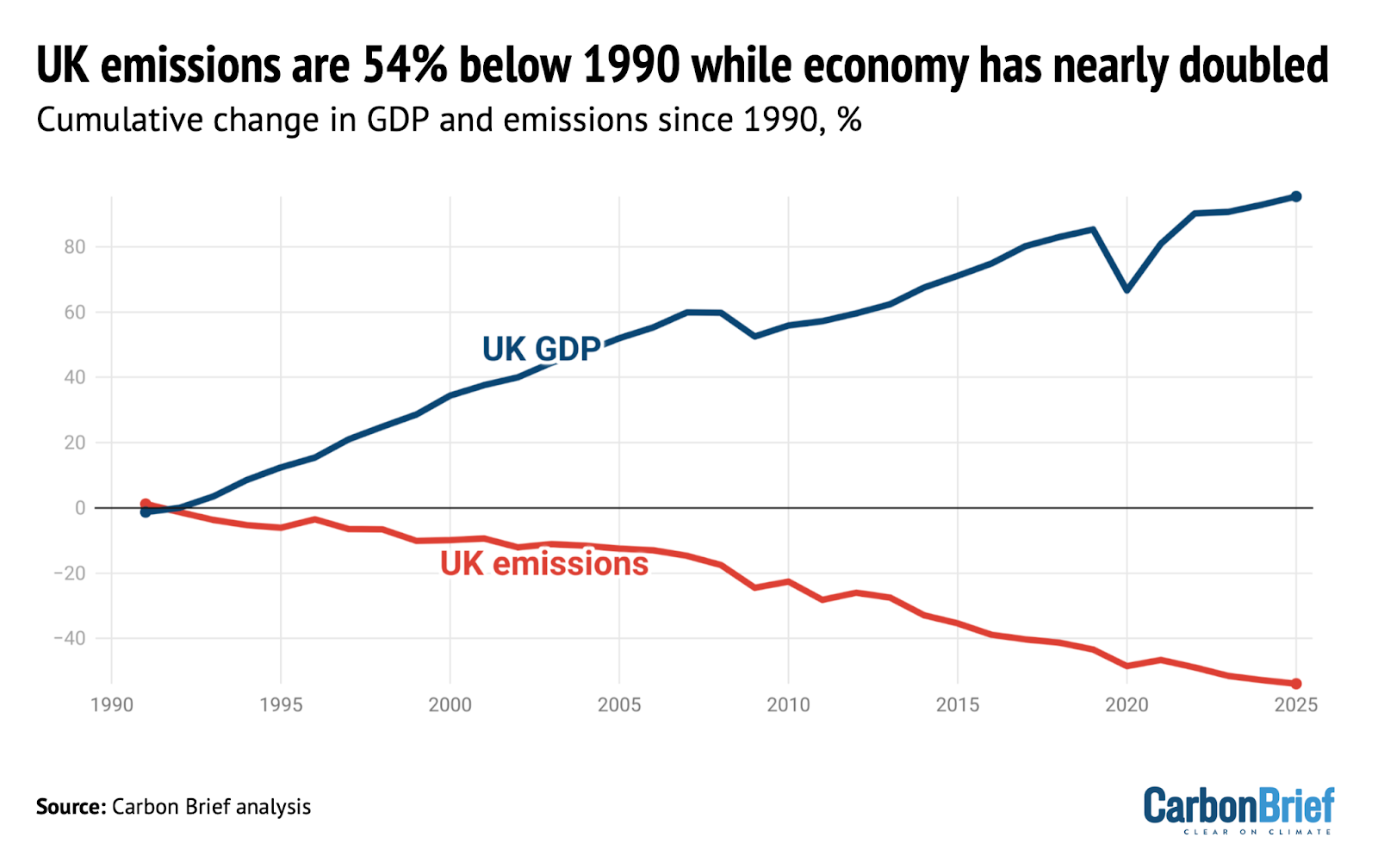

UK greenhouse gas emissions in 2025 fell to 54% below 1990 levels, the baseline year for its legally binding climate goals, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Over the same period, data from the World Bank shows that the UK’s economy has expanded by 95%, meaning that emissions have been decoupling from growth.

Spotlight

Bristol’s ‘pioneering’ community wind turbine

Following the recent launch of the UK government’s local power plan, Carbon Brief visits one of the country’s community-energy success stories.

The Lawrence Weston housing estate is set apart from the main city of Bristol, wedged between the tree-lined grounds of a stately home and a sprawl of warehouses and waste incinerators. It is one of the most deprived areas in the city.

Yet, just across the M5 motorway stands a structure that has brought the spoils of the energy transition directly to this historically forgotten estate – a 4.2 megawatt (MW) wind turbine.

The turbine is owned by local charity Ambition Lawrence Weston and all the profits from its electricity sales – around £100,000 a year – go to the community. In the UK’s local power plan, it was singled out by energy secretary Ed Miliband as a “pioneering” project.

‘Sustainable income’

On a recent visit to the estate by Carbon Brief, Ambition Lawrence Weston’s development manager, Mark Pepper, rattled off the story behind the wind turbine.

In 2012, Pepper and his team were approached by the Bristol Energy Cooperative with a chance to get a slice of the income from a new solar farm. They jumped at the opportunity.

“Austerity measures were kicking in at the time,” Pepper told Carbon Brief. “We needed to generate an income. Our own, sustainable income.”

With the solar farm proving to be a success, the team started to explore other opportunities. This began a decade-long process that saw them navigate the Conservative government’s “ban” on onshore wind, raise £5.5m in funding and, ultimately, erect the turbine in 2023.

Today, the turbine generates electricity equivalent to Lawrence Weston’s 3,000 households and will save 87,600 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) over its lifetime.

‘Climate by stealth’

Ambition Lawrence Weston’s hub is at the heart of the estate and the list of activities on offer is seemingly endless: birthday parties, kickboxing, a library, woodworking, help with employment and even a pop-up veterinary clinic. All supported, Pepper said, with the help of a steady income from community-owned energy.

The centre itself is kitted out with solar panels, heat pumps and electric-vehicle charging points, making it a living advertisement for the net-zero transition. Pepper noted that the organisation has also helped people with energy costs amid surging global gas prices.

Gesturing to the England flags dangling limply on lamp posts visible from the kitchen window, he said:

“There’s a bit of resentment around immigration and scarcity of materials and provision, so we’re trying to do our bit around community cohesion.”

This includes supper clubs and an interfaith grand iftar during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

Anti-immigration sentiment in the UK has often gone hand-in-hand with opposition to climate action. Right-wing politicians and media outlets promote the idea that net-zero policies will cost people a lot of money – and these ideas have cut through with the public.

Pepper told Carbon Brief he is sympathetic to people’s worries about costs and stressed that community energy is the perfect way to win people over:

“I think the only way you can change that is if, instead of being passive consumers…communities are like us and they’re generating an income to offset that.”

From the outset, Pepper stressed that “we weren’t that concerned about climate because we had other, bigger pressures”, adding:

“But, in time, we’ve delivered climate by stealth.”

Watch, read, listen

OIL WATCH: The Guardian has published a “visual guide” with charts and videos showing how the “escalating Iran conflict is driving up oil and gas prices”.

MURDER IN HONDURAS: Ten years on from the murder of Indigenous environmental justice advocate Berta Cáceres, Drilled asked why Honduras is still so dangerous for environmental activists.

TALKING WEATHER: A new film, narrated by actor Michael Sheen and titled You Told Us To Talk About the Weather, aimed to promote conversation about climate change with a blend of “poetry, folk horror and climate storytelling”.

Coming up

- 8 March: Colombia parliamentary election

- 9-19 March: 31st Annual Session of the International Seabed Authority, Kingston, Jamaica

- 11 March: UN Environment Programme state of finance for nature 2026 report launch

Pick of the jobs

- London School of Economics and Political Science, fellow in the social science of sustainability | Salary: £43,277-£51,714. Location: London

- NORCAP, innovative climate finance expert | Salary: Unknown. Location: Kyiv, Ukraine

- WBHM, environmental reporter | Salary: $50,050-$81,330. Location: Birmingham, Alabama, US

- Climate Cabinet, data engineer | Salary: hourly rate of $60-$120 per hour. Location: Remote anywhere in the US

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 6 March 2026: Iran energy crisis | China climate plan | Bristol’s ‘pioneering’ wind turbine appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Q&A: What does China’s 15th ‘five-year plan’ mean for climate change?

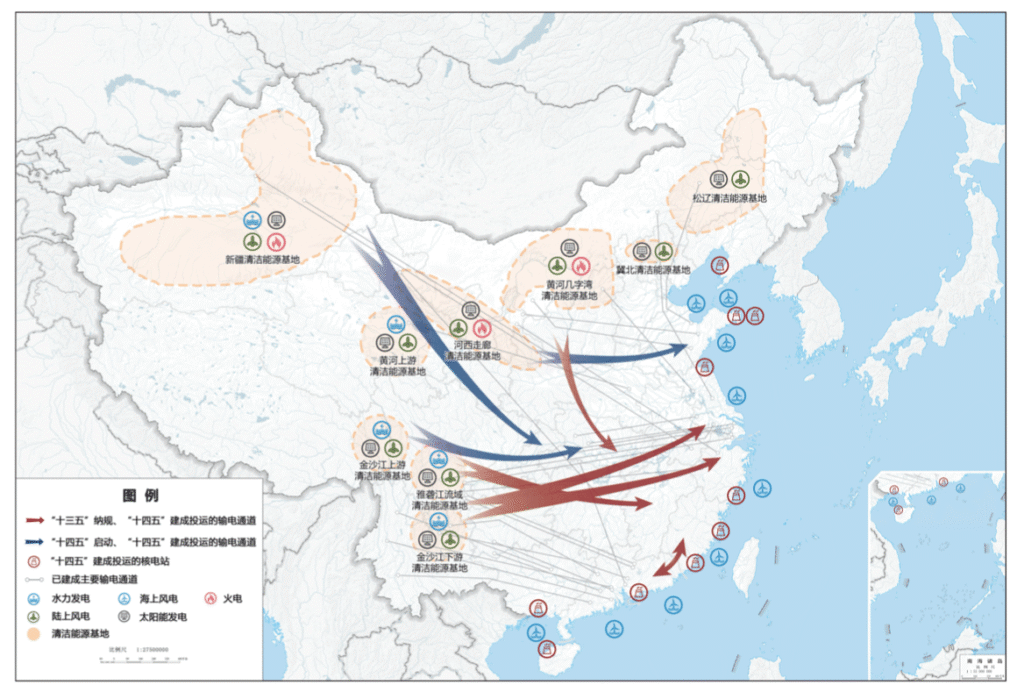

China’s leadership has published a draft of its 15th five-year plan setting the strategic direction for the nation out to 2030, including support for clean energy and energy security.

The plan sets a target to cut China’s “carbon intensity” by 17% over the five years from 2026-30, but also changes the basis for calculating this key climate metric.

The plan continues to signal support for China’s clean-energy buildout and, in general, contains no major departures from the country’s current approach to the energy transition.

The government reaffirms support for several clean-energy industries, ranging from solar and electric vehicles (EVs) through to hydrogen and “new-energy” storage.

The plan also emphasises China’s willingness to steer climate governance and be seen as a provider of “global public goods”, in the form of affordable clean-energy technologies.

However, while the document says it will “promote the peaking” of coal and oil use, it does not set out a timeline and continues to call for the “clean and efficient” use of coal.

This shows that tensions remain between China’s climate goals and its focus on energy security, leading some analysts to raise concerns about its carbon-cutting ambition.

Below, Carbon Brief outlines the key climate change and energy aspects of the plan, including targets for carbon intensity, non-fossil energy and forestry.

Note: this article is based on a draft published on 5 March and will be updated if any significant changes are made in the final version of the plan, due to be released at the close next week of the “two sessions” meeting taking place in Beijing.

- What is China’s 15th five-year plan?

- What does the plan say about China’s climate action?

- What is China’s new CO2 intensity target?

- Does the plan encourage further clean-energy additions?

- What does the plan signal about coal?

- How will China approach global climate governance in the next five years?

- What else does the plan cover?

What is China’s 15th five-year plan?

Five-year plans are one of the most important documents in China’s political system.

Addressing everything from economic strategy to climate policy, they outline the planned direction for China’s socio-economic development in a five-year period. The 15th five-year plan covers 2026-30.

These plans include several “main goals”. These are largely quantitative indicators that are seen as particularly important to achieve and which provide a foundation for subsequent policies during the five-year period.

The table below outlines some of the key “main goals” from the draft 15th five-year plan.

| Category | Indicator | Indicator in 2025 | Target by 2030 | Cumulative target over 2026-2030 | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic development | Gross domestic product (GDP) growth (%) | 5 | Maintained within a reasonable range and proposed annually as appropriate. | Anticipatory | |

| ‘Green and low-carbon | Reduction in CO2 emissions per unit of GDP (%) | 17.7 | 17 | Binding | |

| Share of non-fossil energy in total energy consumption (%) | 21.7 | 25 | Binding | ||

| Security guarantee | Comprehensive energy production capacity (100m tonnes of standard coal equivalent) |

51.3 | 58 | Binding |

Select list of targets highlighted in the “main goals” section of the draft 15th five-year plan. Source: Draft 15th five-year plan.

Since the 12th five-year plan, covering 2011-2015, these “main goals” have included energy intensity and carbon intensity as two of five key indicators for “green ecology”.

The previous five-year plan, which ran from 2021-2025, introduced the idea of an absolute “cap” on carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, although it did not provide an explicit figure in the document. This has been subsequently addressed by a policy on the “dual-control of carbon” issued in 2024.

The latest plan removes the energy-intensity goal and elevates the carbon-intensity goal, but does not set an absolute cap on emissions (see below).

It covers the years until 2030, before which China has pledged to peak its carbon emissions. (Analysis for Carbon Brief found that emissions have been “flat or falling” since March 2024.)

The plans are released at the two sessions, an annual gathering of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). This year, it runs from 4-12 March.

The plans are often relatively high-level, with subsequent topic-specific five-year plans providing more concrete policy guidance.

Policymakers at the National Energy Agency (NEA) have indicated that in the coming years they will release five sector-specific plans for 2026-2030, covering topics such as the “new energy system”, electricity and renewable energy.

There may also be specific five-year plans covering carbon emissions and environmental protection, as well as the coal and nuclear sectors, according to analysts.

Other documents published during the two sessions include an annual government work report, which outlines key targets and policies for the year ahead.

The gathering is attended by thousands of deputies – delegates from across central and local governments, as well as Chinese Communist party members, members of other political parties, academics, industry leaders and other prominent figures.

What does the plan say about China’s climate action?

Achieving China’s climate targets will remain a key driver of the country’s policies in the next five years, according to the draft 15th five-year plan.

It lists the “acceleration” of China’s energy transition as a “major achievement” in the 14th five-year plan period (2021-2025), noting especially how clean-power capacity had overtaken fossil fuels.

The draft says China will “actively and steadily advance and achieve carbon peaking”, with policymakers continuing to strike a balance between building a “green economy” and ensuring stability.

Climate and environment continues to receive its own chapter in the plan. However, the framing and content of this chapter has shifted subtly compared with previous editions, as shown in the table below. For example, unlike previous plans, the first section of this chapter focuses on China’s goal to peak emissions.

| 11th five-year plan (2006-2010) | 12th five-year plan (2011-2015) | 13th five-year plan (2016-2020) | 14th five-year plan (2021-2025) | 15th five-year plan (2026-2030) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chapter title | Part 6: Build a resource-efficient and environmentally-friendly society | Part 6: Green development, building a resource-efficient and environmentally friendly society | Part 10: Ecosystems and the environment | Part 11: Promote green development and facilitate the harmonious coexistence of people and nature | Part 13: Accelerating the comprehensive green transformation of economic and social development to build a beautiful China |

| Sections | Developing a circular economy | Actively respond to global climate change | Accelerate the development of functional zones | Improve the quality and stability of ecosystems | Actively and steadily advancing and achieving carbon peaking |

| Protecting and restoring natural ecosystems | Strengthen resource conservation and management | Promote economical and intensive resource use | Continue to improve environmental quality | Continuously improving environmental quality | |

| Strengthening environmental protection | Vigorously develop the circular economy | Step up comprehensive environmental governance | Accelerate the green transformation of the development model | Enhancing the diversity, stability, and sustainability of ecosystems | |

| Enhancing resource management | Strengthen environmental protection efforts | Intensify ecological conservation and restoration | Accelerating the formation of green production and lifestyles | ||

| Rational utilisation of marine and climate resources | Promoting ecological conservation and restoration | Respond to global climate change | |||

| Strengthen the development of water conservancy and disaster prevention and mitigation systems | Improve mechanisms for ensuring ecological security | ||||

| Develop green and environmentally-friendly industries |

Title and main sections of the climate and environment-focused chapters in the last five five-year plans. Source: China’s 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th and 15th five-year plans.

The climate and environment chapter in the latest plan calls for China to “balance [economic] development and emission reduction” and “ensure the timely achievement of carbon peak targets”.

Under the plan, China will “continue to pursue” its established direction and objectives on climate, Prof Li Zheng, dean of the Tsinghua University Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development (ICCSD), tells Carbon Brief.

What is China’s new CO2 intensity target?

In the lead-up to the release of the plan, analysts were keenly watching for signals around China’s adoption of a system for the “dual-control of carbon”.

This would combine the existing targets for carbon intensity – the CO2 emissions per unit of GDP – with a new cap on China’s total carbon emissions. This would mark a dramatic step for the country, which has never before set itself a binding cap on total emissions.

Policymakers had said last year that this framework would come into effect during the 15th five-year plan period, replacing the previous system for the “dual-control of energy”.

However, the draft 15th five-year plan does not offer further details on when or how both parts of the dual-control of carbon system will be implemented. Instead, it continues to focus on carbon intensity targets alone.

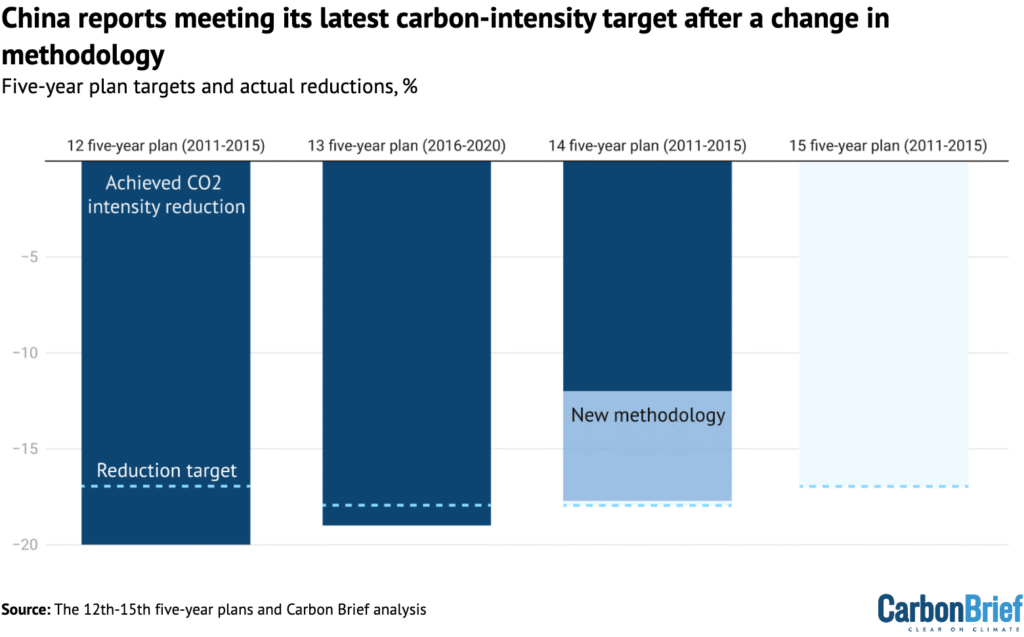

Looking back at the previous five-year plan period, the latest document says China had achieved a carbon-intensity reduction of 17.7%, just shy of its 18% goal.

This is in contrast with calculations by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), which had suggested that China had only cut its carbon intensity by 12% over the past five years.

At the time it was set in 2021, the 18% target had been seen as achievable, with analysts telling Carbon Brief that they expected China to realise reductions of 20% or more.

However, the government had fallen behind on meeting the target.

Last year, ecology and environment minister Huang Runqiu attributed this to the Covid-19 pandemic, extreme weather and trade tensions. He said that China, nevertheless, remained “broadly” on track to meet its 2030 international climate pledge of reducing carbon intensity by more than 65% from 2005 levels.

Myllyvirta tells Carbon Brief that the newly reported figure showing a carbon-intensity reduction of 17.7% is likely due to an “opportunistic” methodological revision. The new methodology now includes industrial process emissions – such as cement and chemicals – as well as the energy sector.

(This is not the first time China has redefined a target, with regulators changing the methodology for energy intensity in 2023.)

For the next five years, the plan sets a target to reduce carbon intensity by 17%, slightly below the previous goal.

However, the change in methodology means that this leaves space for China’s overall emissions to rise by “3-6% over the next five years”, says Myllyvirta. In contrast, he adds that the original methodology would have required a 2% fall in absolute carbon emissions by 2030.