Last year, China started construction on an estimated 95 gigawatts (GW) of new coal power capacity, enough to power the entire UK twice over.

It accounted for 93% of new global coal-power construction in 2024.

The boom appears to contradict China’s climate commitments and its pledge to “strictly control” new coal power.

The fact that China already has significant underused coal power capacity and is adding enough clean energy to cover rising electricity demand also calls the necessity of the buildout into question.

Furthermore, so much new coal capacity provides an easy counterargument for claims that China is serious about the energy transition.

Did China really need more coal power?

And now that it is here, do all these brand-new power plants mean China’s greenhouse gas emissions will remain elevated for longer?

This article addresses four common talking points surrounding China’s ongoing coal-power expansion, explaining how and why the current wave of new projects might come to an end.

New coal is not needed for energy security

The explanation for China’s recent coal boom lies in a combination of policy priorities, institutional incentives and system-level mismatches, with origins in the widespread power shortages China experienced in the early 2020s.

In 2021, a “mismatch” between the price of coal and the government-set price of coal-fired power incentivised coal-fired power plants to cut generation. Furthermore, power shortages in 2020 and 2022 revealed issues of inflexible grid management and limited availability of power plants, when demand spiked due to extreme weather and elevated energy-intensive economic activity, compounded by coal shortages, reduced hydro output and insufficient imported electricity import.

Following this, energy security became a top priority for the central government. Local governments responded by approving new coal-power projects as a form of insurance against future outages.

Yet, on paper, China had – and still has – more than enough “dispatchable” resources to meet even the highest demand peaks. (Dispatchable sources include coal, gas, nuclear and hydropower.) It also has more than enough underutilised coal-power capacity to meet potential demand growth.

A bigger factor behind the shortages was grid inflexibility. During both the 2020 power crisis in north-east China and the 2022 shortage in Sichuan, affected provinces continued to export electricity while experiencing local shortages.

A lack of coordination between provinces and inflexible market mechanisms governing the “dispatch” of power plants – the instructions to adjust generation up or down – meant that existing resources could not be fully utilised.

Nevertheless, with coal power plants cheap to build and quick to gain approval, many provinces saw them as a reliable way to reassure policymakers, balance local grids and support industry interests, regardless of whether the plants would end up being economically viable or frequently used.

China’s average utilisation rate of coal power plants in 2024 was around 50%, meaning total coal-fired electricity generation could rise substantially without the need for any new capacity.

At the same time as adding new coal, the Chinese government also addressed energy security through improvements to grid operation and market reforms, as well as building more storage.

The country added dozens of gigawatts of battery storage, accelerated pumped hydro projects and improved trading linkages between electricity markets in different provinces.

Though these investments could have gone further, they have already helped avoid blackouts during recent summers – when few of the newly-permitted coal power plants had come online. As such, it is not clear that the new coal plants were needed to guarantee security of supply in the first place.

President Xi Jinping has stated that “energy security depends on developing new energy” – using the Chinese term for renewables excluding hydropower and sometimes including nuclear. According to the International Energy Agency, in the long run, resilience will come not from overbuilding coal, but from modernising China’s power system.

New coal power plants do not mean more coal use and higher emissions

It may seem intuitive to imagine that if a country is building new coal power plants, it will automatically burn more coal and increase its emissions.

But adding capacity does not necessarily translate into higher generation or emissions, particularly while the growth of clean energy is still accelerating.

Coal power generation plays a residual role in China’s power system, filling the gap between the power generated from clean energy sources – such as wind, solar, hydro and nuclear – and total electricity demand. As clean-energy generation is growing rapidly, the space left for coal to fill is shrinking.

From December 2024, coal power generation declined for five straight months before ticking up slightly in May and June, mainly to offset weaker hydropower generation due to drought. Coal power generation was flat overall in the second quarter of 2025.

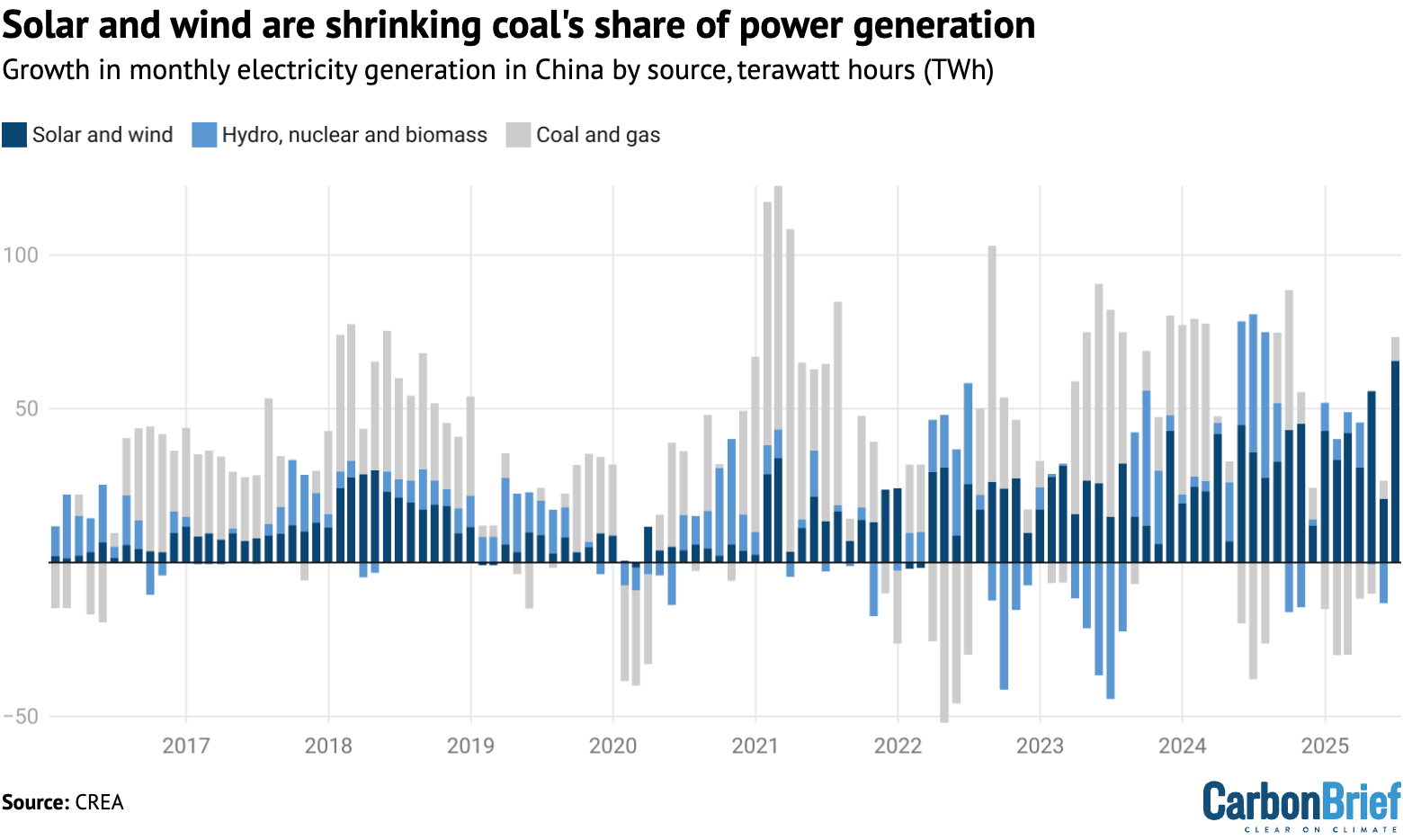

The chart below shows growth in monthly power generation for coal and gas (grey), solar and wind (dark blue) and other low-carbon power sources (light blue).

This illustrates how the rise in wind and solar growth is squeezing the residual demand left for coal power, resulting in declining coal-power output during much of 2025 to date.

Another way to consider the impact of new coal-fired capacity is to test whether, in reality, it automatically leads to a rise in coal-fired electricity generation.

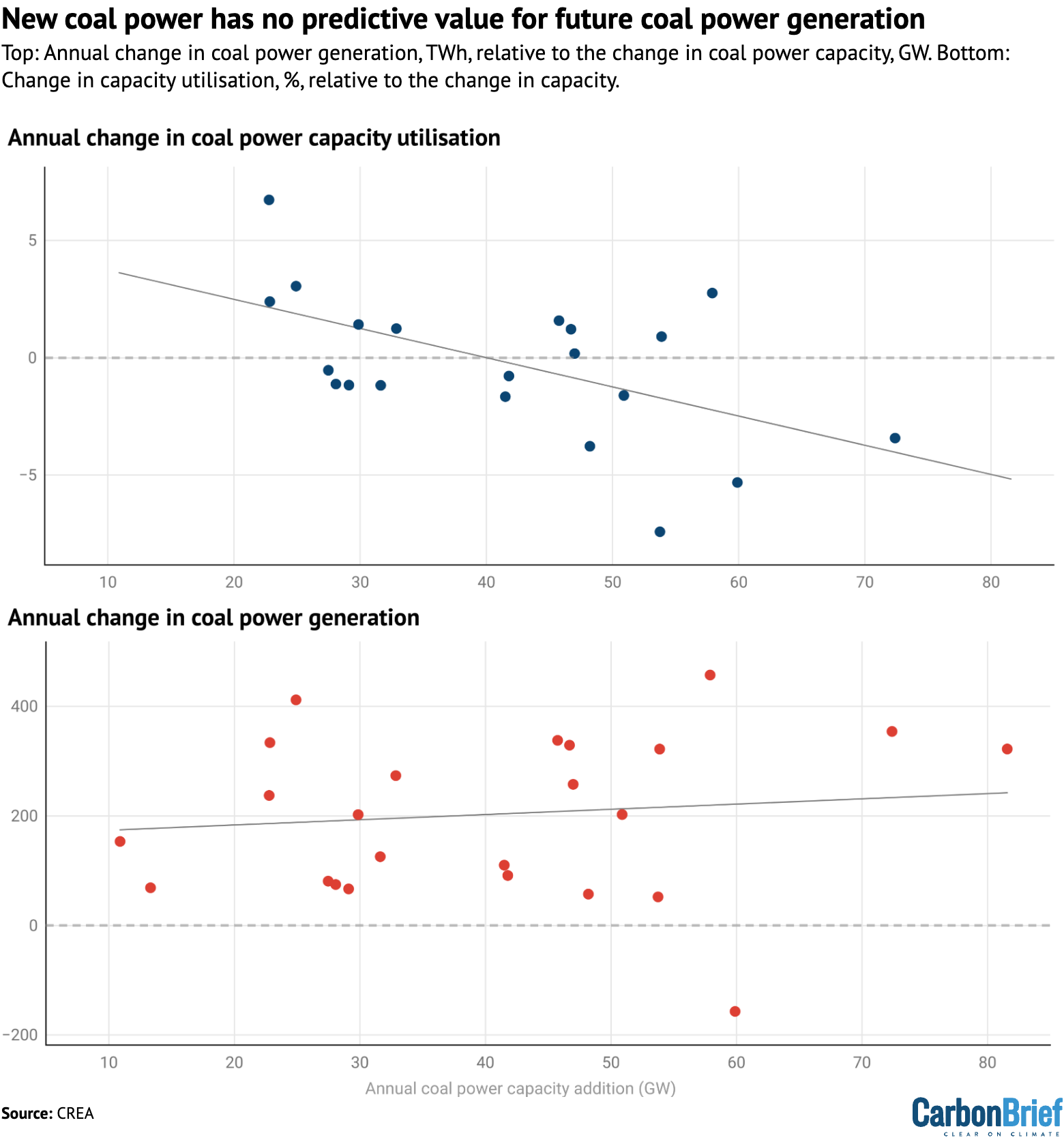

The top panel in the figure below shows the annual increase in coal power capacity on the horizontal axis, relative to the change in coal-power output on the vertical axis.

For example, in 2023, China added 47GW of new coal capacity and coal power output rose by 3.4TWh. In contrast, only 28GW was added in 2021, yet output still rose by 4.4TWh.

In other words, there is no correlation between the amount of new coal capacity and the change in electricity generation from coal, or the associated emissions, on an annual basis.

Indeed, the lower panel in the figure shows that larger additions of coal capacity are often followed by falling utilisation. This means that adding coal plants tends to mean that the coal fleet overall is simply used less often.

As such, while adding new coal plants might complicate the energy transition and may increase the risk of unnecessary greenhouse gas emissions, an increase in coal use is far from guaranteed.

If instead, clean energy is covering all new demand – as it has been recently – then building new coal plants simply means that the coal fleet will be increasingly underutilised, which poses a threat to plant profitability.

China is not unique in its approach to coal power

The dynamics behind last year’s surge in coal power project construction starts speak to the logic of China’s system, in which cost-efficiency is not always a central concern when ensuring that key problems are solved.

If a combination of three tools – coal power plants, storage and grid flexibility, in this case – can solve a problem more reliably than one alone, then China is likely to deploy all three, even at the risk of overcapacity.

This approach reflects not just a desire for reliability, but also deeper institutional dynamics that help to explain why coal power continues to be built.

But that does not mean that such a pattern is unique to China.

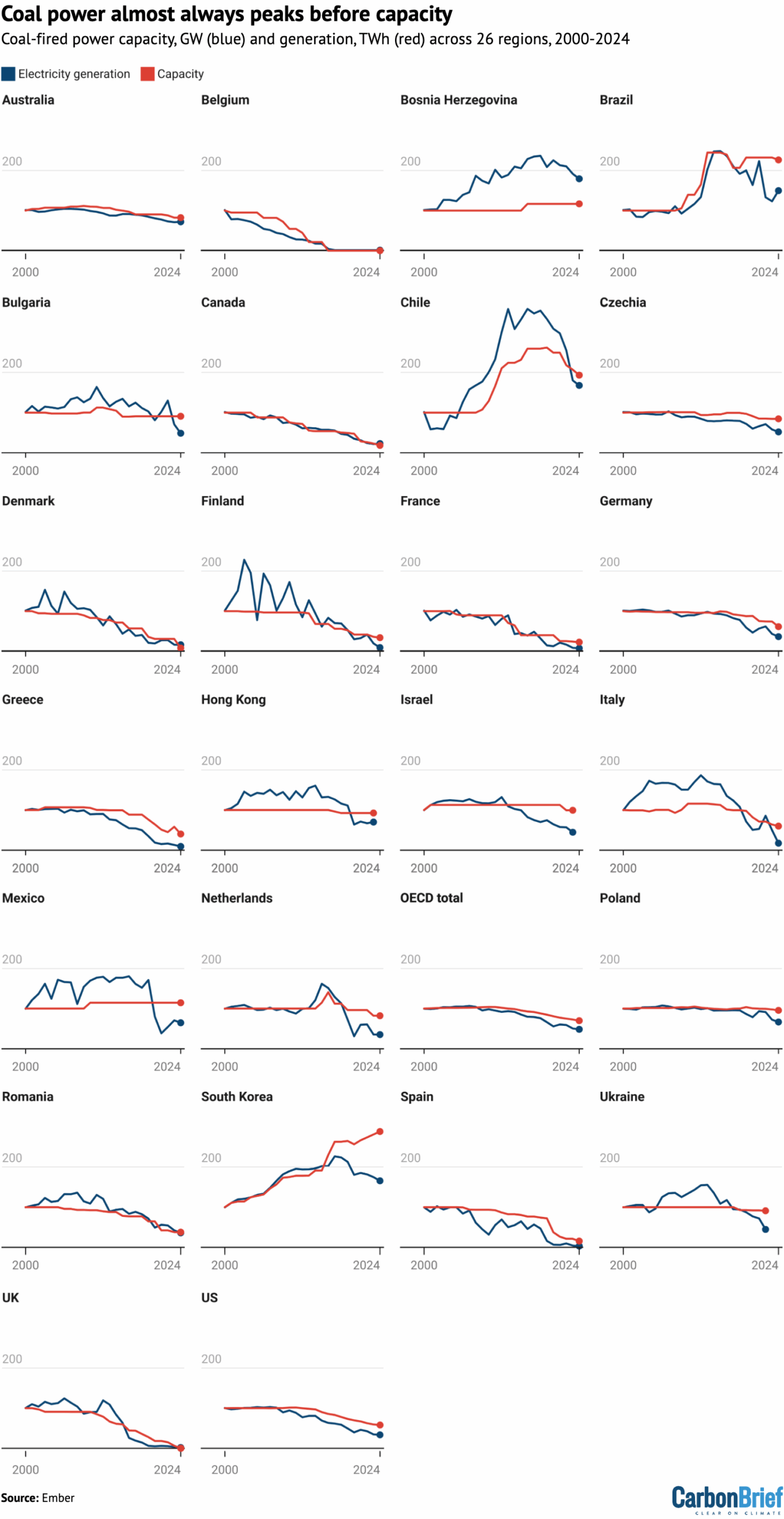

The figure below shows that, across 26 regions, a peak in coal-fired electricity generation (blue lines) almost always comes before coal power capacity (red) starts to decline.

Moreover, the data suggests that once there has been a peak, generation falls much more sharply than capacity, implying that remaining coal plants are kept on the system even as they are used increasingly infrequently.

In most cases, what ultimately stopped new coal power projects in those countries was not a formal ban, but the market reality that they were no longer needed once lower-carbon technologies and efficiency gains began to cover demand growth.

Coal phase-out policies have tended to reinforce these shifts, rather than initiating them. In China, the same market signals are emerging: clean energy is now meeting all incremental demand and coal power generation has, as a result, started to decline.

Coal is not yet playing a flexible ‘supporting’ role

Since 2022, China’s energy policy has stated that new coal-power projects should serve a “supporting” or “regulating” role, helping integrate variable renewables and respond to demand fluctuations, rather than operating as always-on “baseload” generators.

More broadly, China’s energy strategy also calls for coal power to gradually shift away from a dominant baseload role toward a more flexible, supporting function.

These shifts have, however, mostly happened on paper. Coal power overall remains dominant in China’s power mix and largely inflexible in how it is dispatched.

The 2022 policy provided local governments with a new rationale for building coal power, but many of the new plants are still designed and operated as inflexible baseload units. Long-term contracts and guaranteed operating hours often support these plants to run frequently, undermining the idea that they are just backups.

Old coal plants also continue to operate under traditional baseload assumptions. Despite policies promoting retrofits to improve flexibility, coal power remains structurally rigid.

Technical limitations, long-term contracts and economic incentives continue to prevent meaningful change. Coal is unlikely to shift into the flexible supporting role that China says it wants without deeper reform to dispatch rules, pricing mechanisms and contract structures.

Despite all this, China is seeing a clear shift away from coal. Clean-energy installations have surged, while power demand growth has moderated.

As a result, coal power’s share in the electricity mix has steadily declined, dropping from around 73% in 2016 to 51% in June 2025. The chart below shows the monthly power generation share of coal (dark grey), gas (light grey), solar and wind (dark blue), and other low-carbon sources (light blue) from 2016 to the present.

When will the coal boom end?

About a decade ago, the end of China’s coal power expansion also looked near. Coal power plant utilisation declined sharply in the mid-2010s as overcapacity worsened. In response, the government began restricting new project approvals in 2016.

With new construction slowing and power demand rebounding, especially during and after the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, utilisation rates recovered. Not long after, power shortages kicked off the recent coal building spree.

Now, there are new signs that the coal power boom is approaching its end. Permitting is becoming more selective again in some regions, especially in eastern provinces where demand growth is slowing and clean energy is surging. Meanwhile, system flexibility is advancing.

Compared to the late 2010s, the current shift appears more structural. It is driven by the rapid expansion of clean energy, which increasingly eliminates the need for large-scale new coal power projects.

Still, the pace of change will depend on how quickly institutions adapt. If grid operators become confident that peak loads can reliably be met with renewables and flexible backup, the rationale for new coal power plants will weaken.

Equally important, entrenched interests at the provincial and corporate levels continue to push for new plants, not just as insurance, but as sources of investment, employment and revenue. Through long-term contracts and utilisation guarantees, this represents institutional lock-in that may delay the shift away from coal.

The next major turning point will come when coal power utilisation rates begin to fall more sharply and persistently. With large amounts of capacity set to come online in the next two years and clean energy steadily displacing coal in the power mix, a sharp drop in coal power plant utilisation appears likely.

Once this happens, the central government might be expected to step in through administrative capacity cuts – forcing the oldest plants to retire – just as it did during overcapacity campaigns in the steel, cement and coal sectors around 2016 and 2017.

In that sense, China’s coal power phase-out may not begin with a single grand policy declaration, but with a familiar pattern of centralised control and managed retrenchment.

A key question is how quickly institutional incentives and grid operation will catch up with the dawning reality of coal being squeezed by renewable growth, as well as whether they will allow clean energy to lead, or continue to be held back by the legacy of coal.

The upcoming 15th five-year plan presents a crucial test of government priorities in this area. If it wants to bring policy back in line with its long-term climate and energy goals, then it could consider including clear, measurable targets for phasing down coal consumption and limiting new capacity, for example.

While China’s coal power construction boom looks, at first glance, like a resurgence,it currently appears more likely to be the final surge before a long downturn. The expansion has added friction and complexity to China’s energy transition, but it has not reversed it.

The post Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Clean energy drove more than a third of China’s GDP growth in 2025

Solar power, electric vehicles (EVs) and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment.

Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) – comparable to the economies of Brazil or Canada.

The new analysis for Carbon Brief, based on official figures, industry data and analyst reports, shows that China’s clean-energy sectors nearly doubled in real value between 2022-25 and – if they were a country – would now be the 8th-largest economy in the world.

Other key findings from the analysis include:

- Without clean-energy sectors, China would have missed its target for GDP growth of “around 5%”, expanding by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%.

- Clean-energy industries are expanding much more quickly than China’s economy overall, with their annual growth rate accelerating from 12% in 2024 to 18% in 2025.

- The “new three” of EVs, batteries and solar continue to dominate the economic contribution of clean energy in China, generating two-thirds of the value added and attracting more than half of all investment in the sectors.

- China’s investments in clean energy reached 7.2tn yuan ($1.0tn) in 2025, roughly four times the still sizable $260bn put into fossil-fuel extraction and coal power.

- Exports of clean-energy technologies grew rapidly in 2025, but China’s domestic market still far exceeds the export market in value for Chinese firms.

These investments in clean-energy manufacturing represent a large bet on the energy transition in China and overseas, creating an incentive for the government and enterprises to keep the boom going.

However, there is uncertainty about what will happen this year and beyond, particularly for solar power, where growth has slowed in response to a new pricing system and where central government targets have been set far below the recent rate of expansion.

An ongoing slowdown could turn the sectors into a drag on GDP, while worsening industrial “overcapacity” and exacerbating trade tensions.

Yet, even if central government targets in the next five-year plan are modest, those from local governments and state-owned enterprises could still drive significant growth in clean energy.

This article updates analysis previously reported for 2023 and 2024.

Clean-energy sectors outperform wider economy

China’s clean-energy economy continues to grow far more quickly than the wider economy. This means that it is making an outsize contribution to annual economic growth.

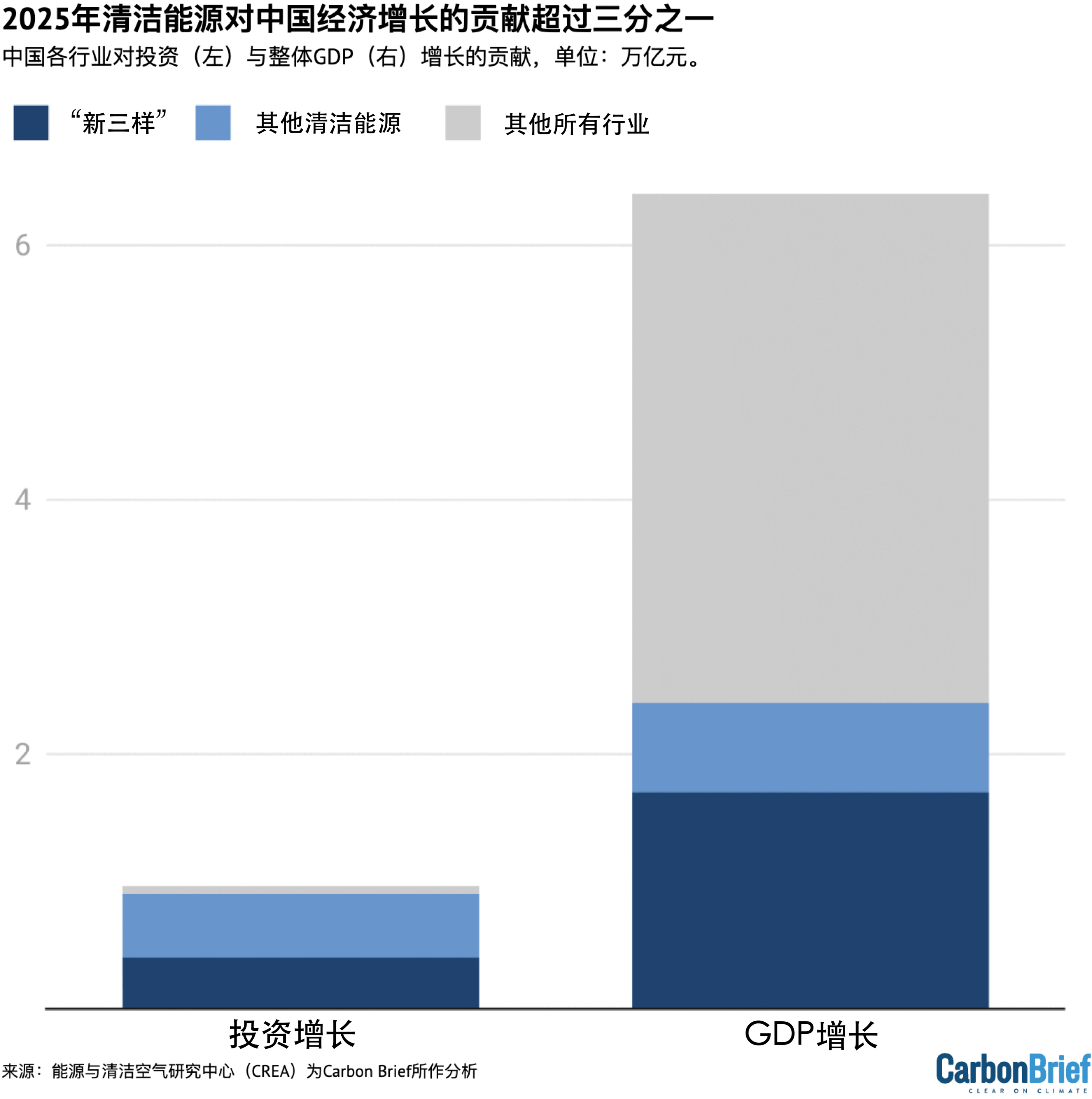

The figure below shows that clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy overall in 2025 and more than 90% of the net rise in investment.

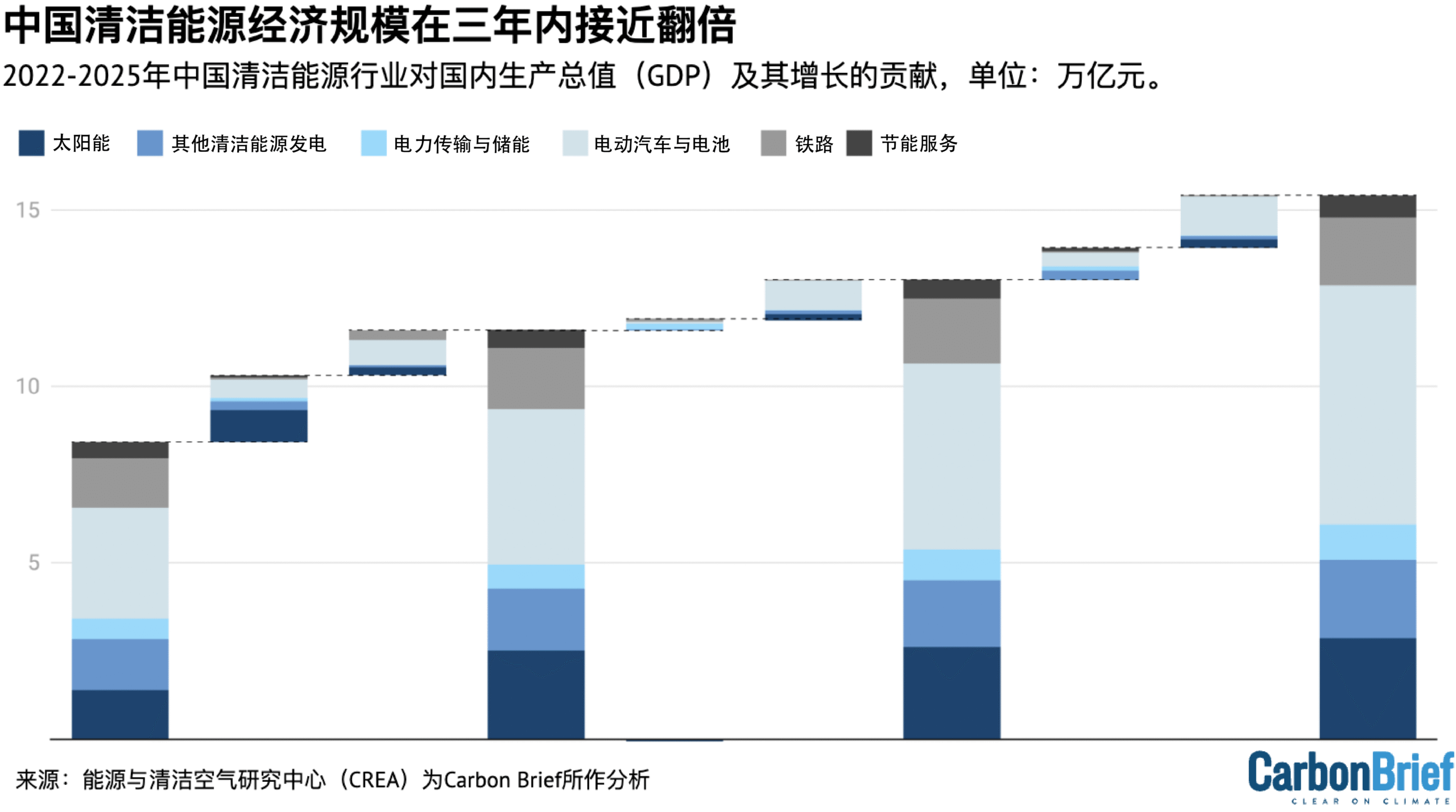

In 2022, China’s clean-energy economy was worth an estimated 8.4tn yuan ($1.2tn). By 2025, the sectors had nearly doubled in value to 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn).

This is comparable to the entire output of Brazil or Canada and positions the Chinese clean-energy industry as the 8th-largest economy in the world. Its value is roughly half the size of the economy of India – the world’s fourth largest – or of the US state of California.

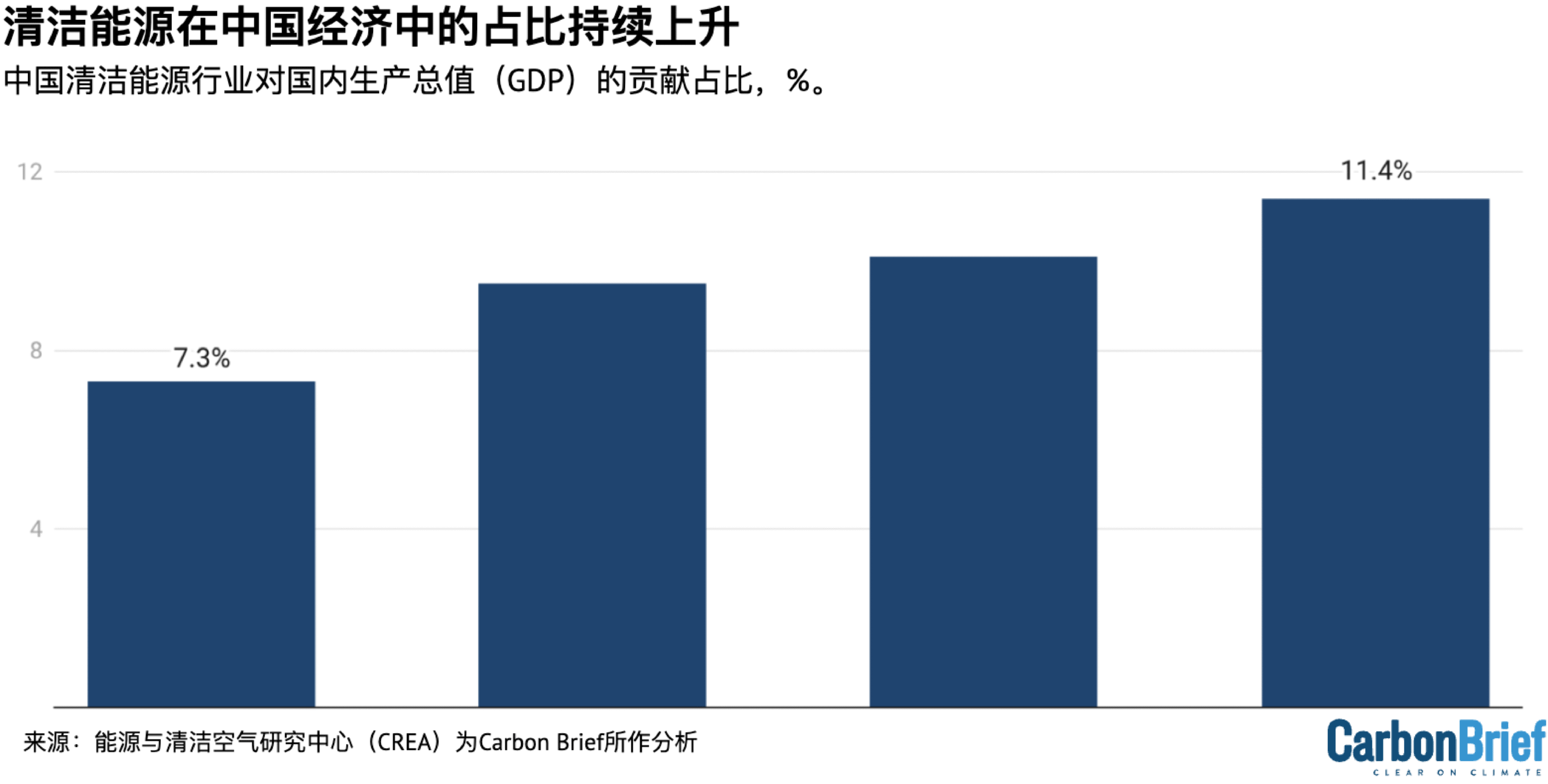

The outperformance of the clean-energy sectors means that they are also claiming a rising share of China’s economy overall, as shown in the figure below.

This share has risen from 7.3% of China’s GDP in 2022 to 11.4% in 2025.

Without clean-energy sectors, China’s GDP would have expanded by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%, missing the target of “around 5%” growth by a wide margin.

Clean energy thus made a crucial contribution during a challenging year, when promoting economic growth was the foremost aim for policymakers.

The table below includes a detailed breakdown by sector and activity.

| Sector | Activity | Value in 2025, CNY bln | Value in 2025, USD bln | Year-on-year growth | Growth contribution | Value contribution | Value in 2025, CNY trn | Value in 2024, CNY trn | Value in 2023, CNY trn | Value in 2022, CNY trn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVs | Investment: manufacturing capacity | 1,643 | 228 | 18% | 10.4% | 10.7% | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| EVs | Investment: charging infrastructure | 192 | 27 | 58% | 2.9% | 1.2% | 0.192 | 0.122 | 0.1 | 0.08 |

| EVs | Production of vehicles | 3,940 | 548 | 29% | 36.4% | 25.6% | 3.94 | 3.065 | 2.26 | 1.65 |

| Batteries | Investment: battery manufacturing | 277 | 38 | 35% | 3.0% | 1.8% | 0.277 | 0.205 | 0.32 | 0.15 |

| Batteries | Exports: batteries | 724 | 101 | 51% | 10.1% | 4.7% | 0.724 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.34 |

| Solar power | Investment: power generation capacity | 1,182 | 164 | 15% | 6.3% | 7.7% | 1.182 | 1.031 | 0.808 | 0.34 |

| Solar power | Investment: manufacturing capacity | 506 | 70 | -23% | -6.5% | 3.3% | 0.506 | 0.662 | 0.95 | 0.51 |

| Solar power | Electricity generation | 491 | 68 | 33% | 5.1% | 3.2% | 0.491 | 0.369 | 0.26 | 0.19 |

| Solar power | Exports of components | 681 | 95 | 21% | 4.9% | 4.4% | 0.681 | 0.562 | 0.5 | 0.35 |

| Wind power | Investment: power generation capacity, onshore | 612 | 85 | 47% | 8.1% | 4.0% | 0.612 | 0.417 | 0.397 | 0.21 |

| Wind power | Investment: power generation capacity, offshore | 96 | 13 | 98% | 2.0% | 0.6% | 0.096 | 0.048 | 0.086 | 0.06 |

| Wind power | Electricity generation | 510 | 71 | 13% | 2.4% | 3.3% | 0.51 | 0.453 | 0.4 | 0.34 |

| Nuclear power | Investment: power generation capacity | 173 | 24 | 18% | 1.1% | 1.1% | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Nuclear power | Electricity generation | 216 | 30 | 8% | 0.7% | 1.4% | 0.216 | 0.2 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Hydropower | Investment: power generation capacity | 54 | 7 | -7% | -0.2% | 0.3% | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Hydropower | Electricity generation | 582 | 81 | 3% | 0.6% | 3.8% | 0.582 | 0.567 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

| Rail transportation | Investment | 902 | 125 | 6% | 2.1% | 5.8% | 0.902 | 0.851 | 0.764 | 0.714 |

| Rail transportation | Transport of passengers and goods | 1,020 | 142 | 3% | 1.3% | 6.6% | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.964 | 0.694 |

| Electricity transmission | Investment: transmission capacity | 644 | 90 | 6% | 1.5% | 4.2% | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.5 |

| Electricity transmission | Transmission of clean power | 52 | 7 | 14% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.052 | 0.046 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Energy storage | Investment: Pumped hydro | 53 | 7 | 5% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Energy storage | Investment: Grid-connected batteries | 232 | 32 | 52% | 3.3% | 1.5% | 0.232 | 0.152 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Energy storage | Investment: Electrolysers | 11 | 2 | 29% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0 | 0 |

| Energy efficiency | Revenue: Energy service companies | 620 | 86 | 17% | 3.8% | 4.0% | 0.62 | 0.528003 | 0.52 | 0.45 |

| Total | Investments | 7,198 | 1001 | 15% | 38.2% | 46.7% | 7.20 | 6.28 | 6.00 | 4.11 |

| Total | Production of goods and services | 8,216 | 1,143 | 22% | 61.8% | 53.3% | 8.22 | 6.73 | 5.58 | 4.32 |

| Total | Total GDP contribution | 15,414 | 2144 | 18% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 15.41 | 13.01 | 11.58 | 8.42 |

EVs and batteries were the largest drivers of GDP growth

In 2024, EVs and solar had been the largest growth drivers. In 2025, it was EVs and batteries, which delivered 44% of the economic impact and more than half of the growth of the clean-energy industries. This was due to strong growth in both output and investment.

The contribution to nominal GDP growth – unadjusted for inflation – was even larger, as EV prices held up year-on-year while the economy as a whole suffered from deflation. Investment in battery manufacturing rebounded after a fall in 2024.

The major contribution of EVs and batteries is illustrated in the figure below, which shows both the overall size of the clean-energy economy and the sectors that added the most to the rise from year to year.

The next largest subsector was clean-power generation, transmission and storage, which made up 40% of the contribution to GDP and 30% of the growth in 2025.

Within the electricity sector, the largest drivers were growth in investment in wind and solar power generation capacity, along with growth in power output from solar and wind, followed by the exports of solar-power equipment and materials.

Investment in solar-panel supply chains, a major growth driver in 2022-23, continued to fall for the second year. This was in line with the government’s efforts to rein in overcapacity and “irrational” price competition in the sector.

Finally, rail transportation was responsible for 12% of the total economic output of the clean-energy sectors, but saw relatively muted growth year-on-year, with revenue up 3% and investment by 6%.

Note that the International Energy Agency (IEA) world energy investment report projected that China invested $627bn in clean energy in 2025, against $257bn in fossil fuels.

For the same sectors as the IEA report, this analysis puts the value of clean-energy investment in 2025 at a significantly more conservative $430bn. The higher figures in this analysis overall are therefore the result of wider sectoral coverage.

Electric vehicles and batteries

EVs and vehicle batteries were again the largest contributors to China’s clean-energy economy in 2025, making up an estimated 44% of value overall.

Of this total, the largest share of both total value and growth came from the production of battery EVs and plug-in hybrids, which expanded 29% year-on-year. This was followed by investment into EV manufacturing, which grew 18%, after slower growth rates in 2024.

Investment in battery manufacturing also rebounded after a drop in 2024, driven by new battery technology and strong demand from both domestic and international markets. Battery manufacturing investment grew by 35% year-on-year to 277bn yuan.

The share of electric vehicles (EVs) will have reached 12% of all vehicles on the road by the end of 2025, up from 9% a year earlier and less than 2% just five years ago.

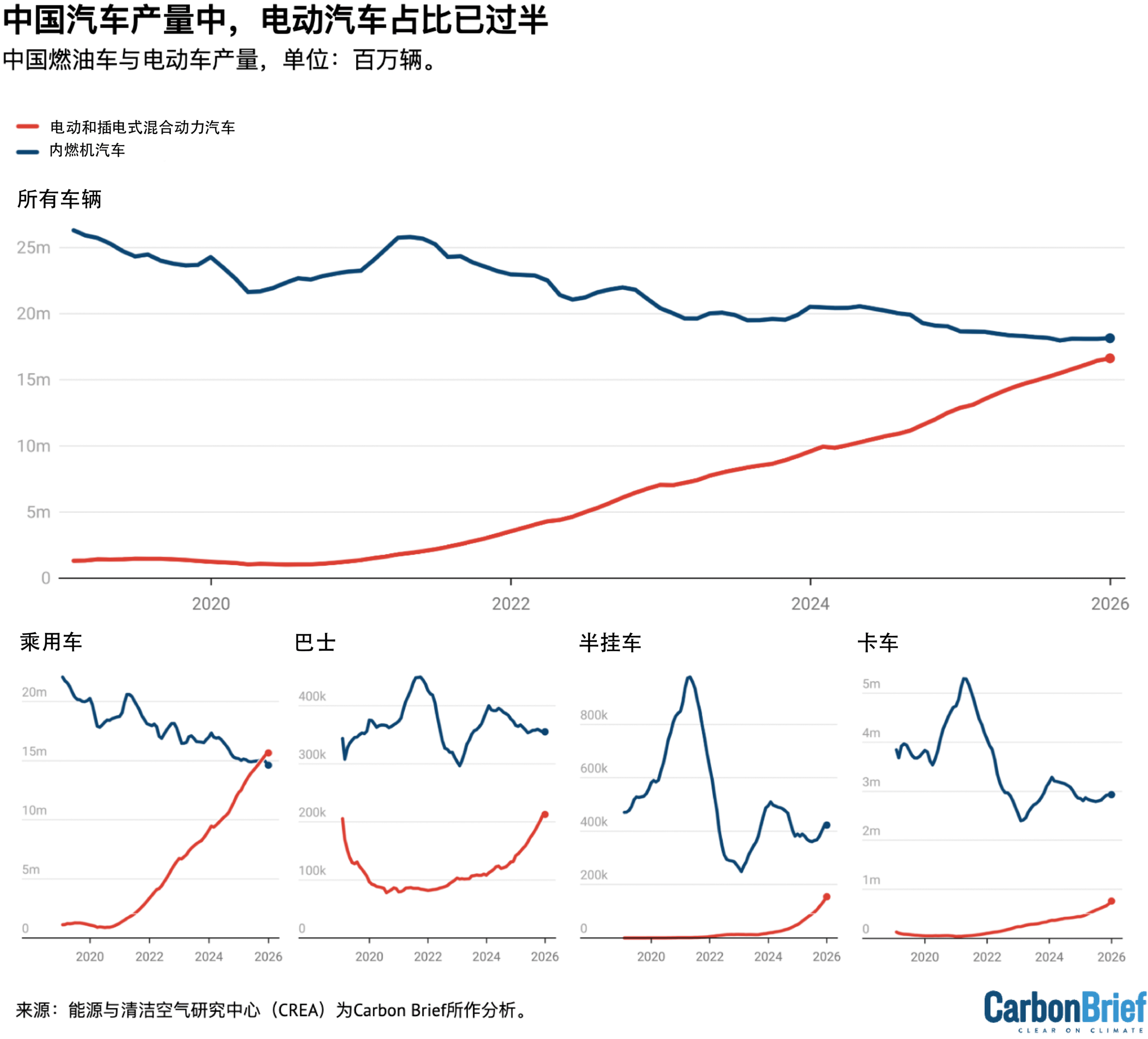

The share of EVs in the sales of all new vehicles increased to 48%, from 41% in 2024, with passenger cars crossing the 50% threshold. In November, EV sales crossed the 60% mark in total sales and they continue to drive overall automotive sales growth, as shown below.

Electric trucks experienced a breakthrough as their market share rose from 8% in the first nine months of 2024 to 23% in the same period in 2025.

Policy support for EVs continues, for example, with a new policy aiming to nearly double charging infrastructure in the next three years.

Exports grew even faster than the domestic market, but the vast majority of EVs continue to be sold domestically. In 2025, China produced 16.6m EVs, rising 29% year-on-year. While exports accounted for only 21% or 3.4m EVs, they grew by 86% year-on-year. Top export destinations for Chinese EVs were western Europe, the Middle East and Latin America.

The value of batteries exported also grew rapidly by 41% year-on-year, becoming the third largest growth driver of the GDP. Battery exports largely went to western Europe, north America and south-east Asia.

In contrast with deflationary trends in the price of many clean-energy technologies, average EV prices have held up in 2025, with a slight increase in average price of new models, after discounts. This also means that the contribution of the EV industry to nominal GDP growth was even more significant, given that overall producer prices across the economy fell by 2.6%. Battery prices continued to drop.

Clean-power generation

The solar power sector generated 19% of the total value of the clean-energy industries in 2025, adding 2.9tn yuan ($41bn) to the national economy.

Within this, investment in new solar power plants, at 1.2tn yuan ($160bn), was the largest driver, followed by the value of solar technology exports and by the value of the power generated from solar. Investment in manufacturing continued to fall after the wave of capacity additions in 2023, reaching 0.5tn yuan ($72bn), down 23% year-on-year.

In 2025, China achieved another new record of wind and solar capacity additions. The country installed a total of 315GW solar and 119GW wind capacity, adding more solar and two times as much wind as the rest of the world combined.

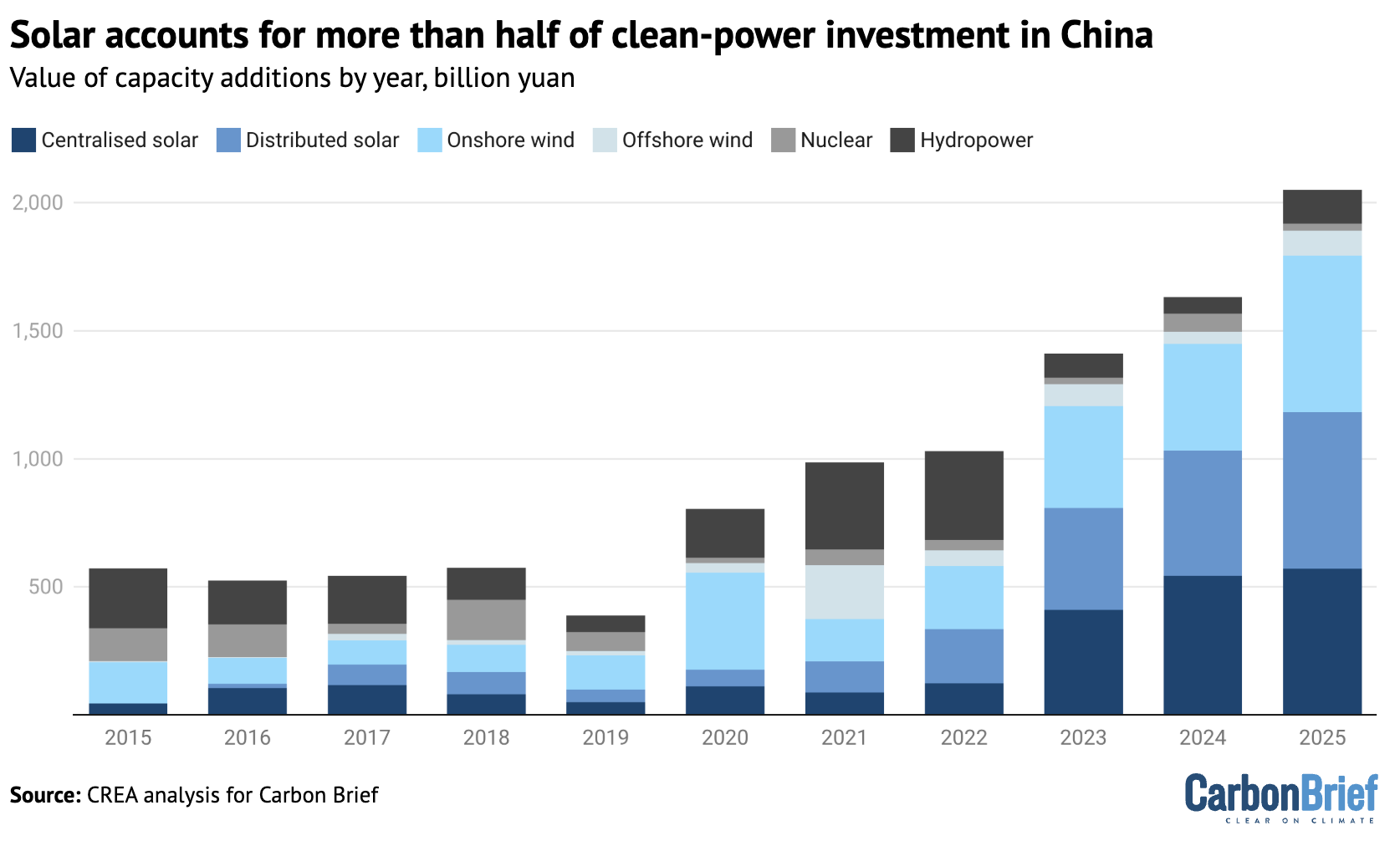

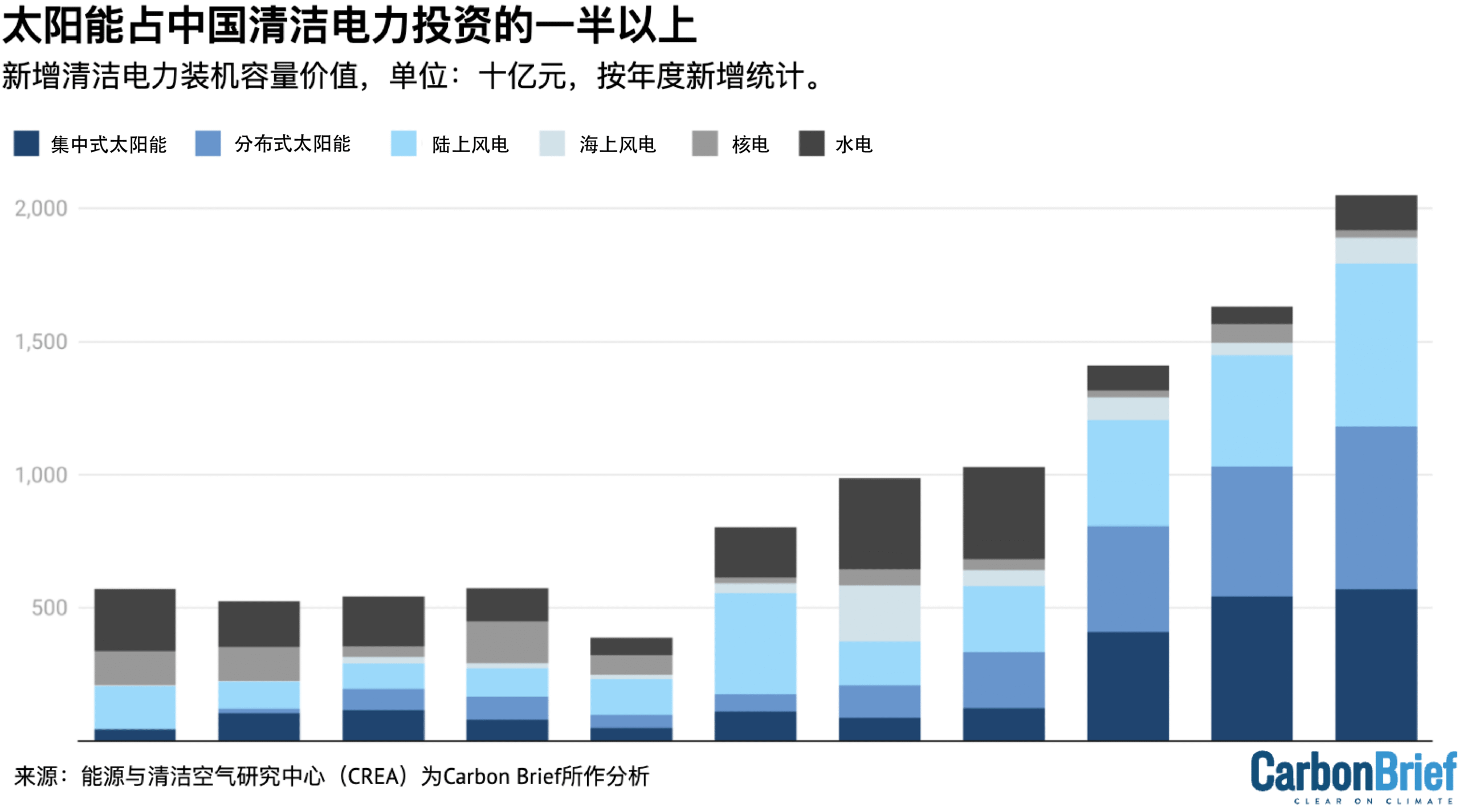

Clean energy accounted for 90% of investment in power generation, with solar alone covering 50% of that. As a result, non-fossil power made up 42% of total power generation, up from 39% in 2024.

However, a new pricing policy for new solar and wind projects and modest targets for capacity growth have created uncertainty about whether the boom will continue.

Under the new policy, new clean-power generation has to compete on price against existing coal power in markets that place it at a disadvantage in some key ways.

At the same time, the electricity markets themselves are still being introduced and developed, creating investment uncertainty.

Investment in solar power generation increased year-on-year by 15%, but experienced a strong stop-and-go cycle. Developers rushed to finish projects ahead of the new pricing policy coming into force in June and then again towards the end of the year to finalise projects ahead of the end of the current 14th five-year plan.

Investment in the solar sector as a whole was stable year-on-year, with the decline in manufacturing capacity investment balanced by continued growth in power generation capacity additions. This helped shore up the utilisation of manufacturing plants, in line with the government’s aim to reduce “disorderly” price competition.

By late 2025, China’s solar manufacturing capacity reached an estimated 1,200GW per year, well ahead of the global capacity additions of around 650GW in 2025. Manufacturers can now produce far more solar panels than the global market can absorb, with fierce competition leading to historically low profitability.

China’s policymakers have sought to address the issue since mid-2024, warning against “involution”, passing regulations and convening a sector-wide meeting to put pressure on the industry. This is starting to yield results, with losses narrowing in the third quarter of 2025.

The volume of exports of solar panels and components reached a record high in 2025, growing 19% year-on-year. In particular, exports of cells and wafers increased rapidly by 94% and 52%, while panel exports grew only by 4%.

This reflects the growing diversification of solar-supply chains in the face of tariffs and with more countries around the world building out solar panel manufacturing capacity. The nominal value of exports fell 8%, however, due to a fall in average prices and a shift to exporting upstream intermediate products instead of finished panels.

Hydropower, wind and nuclear were responsible for 15% of the total value of the clean-energy sectors in 2025, adding some 2.2tn yuan ($310bn) to China’s GDP in 2025.

Nearly two-thirds of this (1.3tn yuan, $180bn) came from the value of power generation from hydropower, wind and nuclear, with investment in new power generation projects contributing the rest.

Power generation grew 33% from solar, 13% from wind, 3% from hydropower and 8% from nuclear.

Within power generation investment, solar remained the largest segment by value – as shown in the figure below – but wind-power generation projects were the largest contributor to growth, overtaking solar for the first time since 2020.

In particular, offshore wind power capacity investment rebounded as expected, doubling in 2025 after a sharp drop in 2024.

Investment in nuclear projects continued to grow but remains smaller in total terms, at 17bn yuan. Investment in conventional hydropower continued to decline by 7%.

Electricity storage and grids

Electricity transmission and storage were responsible for 6% of the total value of the clean-energy sectors in 2025, accounting for 1.0 tn yuan ($140bn).

The most valuable sub-segment was investment in power grids, growing 6% in 2025 and reaching $90bn. This was followed by investment in energy storage, including pumped hydropower, grid-connected battery storage and hydrogen production.

Investment in grid-connected batteries saw the largest year-on-year growth, increasing by 50%, while investments in electrolysers also grew by 30%. The transmission of clean power increased an estimated 13%, due to rapid growth in clean-power generation.

China’s total electricity storage capacity reached more than 213GW, with battery storage capacity crossing 145GW and pumped hydro storage at 69GW. Some 66GW of battery storage capacity was added in 2025, up 52% year-on-year and accounting for more than 40% of global capacity additions.

Notably, capacity additions accelerated in the second half of the year, with 43GW added, compared with the first half, which saw 23GW of new capacity.

The battery storage market initially slowed after the renewable power pricing policy, which banned storage mandates after May, but this was quickly replaced by a “market-driven boom”. Provincial electricity spot markets, time-of-day tariffs and increasing curtailment of solar power all improved the economics of adding storage.

By the end of 2025, China’s top five solar manufacturers had all entered the battery storage market, making a shift in industry strategy.

Investment in pumped hydropower continued to increase, with 15GW of new capacity permitted in the first half of 2025 alone and 3GW entering operation.

Railways

Rail transportation made up 12% of the GDP contribution of the clean-energy sectors, with revenue from passenger and goods rail transportation the largest source of value. Most growth came from investment in rail infrastructure, which increased 6% year-on-year

The electrification of transport is not limited to EVs, as rail passenger, freight and investment volumes saw continued growth. The total length of China’s high-speed railway network reached 50,000km in 2025, making up more than 70% of the global high-speed total.

Energy efficiency

Investment in energy efficiency rebounded strongly in 2025. Measured by the aggregate turnover of large energy service companies (ESCOs), the market expanded by 17% year-on-year, returning to growth rates last seen during 2016-2020.

Total industry turnover has also recovered to its previous peak in 2021, signalling a clear turnaround after three years of weakness.

Industry projections now anticipate annual turnover reaching 1tn yuan in annual turnover by 2030, a target that had previously been expected to be met by 2025.

China’s ESCO market has evolved into the world’s largest. Investment within China’s ESCO market remains heavily concentrated in the buildings sector, which accounts for around 50% of total activity. Industrial applications make up a further 21%, while energy supply, demand-side flexibility and energy storage together account for approximately 16%.

Implications of China’s clean-energy bet

Ongoing investment of hundreds of billions of dollars into clean-energy manufacturing represents a gigantic economic and financial bet on a continuing global energy transition.

In addition to the domestic investment covered in this article, Chinese firms are making major investments in overseas manufacturing.

The clean-energy industries have played a crucial role in meeting China’s economic targets during the five-year period ending this year, delivering an estimated 40%, 25% and 37% of all GDP growth in 2023, 2024 and 2025, respectively.

However, the developments next year and beyond are unclear, particularly for solar power generation, with the new pricing system for renewable power generation leading to a short-term slowdown and creating major uncertainty, while central government targets have been set far below current rates of clean-electricity additions.

Investment in solar-power generation and solar manufacturing declined in the second half of the year, while investment in generation clocked growth for the full year, showing the risk to the industries under the current power market set-ups that favour coal-fired power.

The reduction in the prices of clean-energy technology has been so dramatic that when the prices for GDP statistics are updated, the sectors’ contribution to real GDP – adjusted for inflation or, in this case deflation – will be revised down.

Nevertheless, the key economic role of the industry creates a strong motivation to keep the clean-energy boom going. A slowdown in the domestic market could also undermine efforts to stem overcapacity and inflame trade tensions by increasing pressure on exports to absorb supply.

A recent CREA survey of experts working on climate and energy issues in China found that the majority believe that economic and geopolitical challenges will make the “dual carbon” goals – and with that, clean-energy industries – only more important.

Local governments and state-owned enterprises will also influence the outlook for the sector. Their previous five-year plans played a key role in creating the gigantic wind and solar power “bases” that substantially exceeded the central government’s level of ambition.

Provincial governments also have a lot of leeway in implementing the new electricity markets and contracting systems for renewable power generation. The new five-year plans, to be published this year, will therefore be of major importance.

About the data

Reported investment expenditure and sales revenue has been used where available. When this is not available, estimates are based on physical volumes – gigawatts of capacity installed, number of vehicles sold – and unit costs or prices.

The contribution to real growth is tracked by adjusting for inflation using 2022-2023 prices.

All calculations and data sources are given in a worksheet.

Estimates include the contribution of clean-energy technologies to the demand for upstream inputs such as metals and chemicals.

This approach shows the contribution of the clean-energy sectors to driving economic activity, also outside the sectors themselves, and is appropriate for estimating how much lower economic growth would have been without growth in these sectors.

Double counting is avoided by only including non-overlapping points in value chains. For example, the value of EV production and investment in battery storage of electricity is included, but not the value of battery production for the domestic market, which is predominantly an input to these activities.

Similarly, the value of solar panels produced for the domestic market is not included, as it makes up a part of the value of solar power generating capacity installed in China. However, the value of solar panel and battery exports is included.

In 2025, there was a major divergence between two different measures of investment. The first, fixed asset investment, reportedly fell by 3.8%, the first drop in 35 years. In contrast, gross capital formation saw the slowest growth in that period but still inched up by 2%.

This analysis uses gross capital formation as the measure of investment, as it is the data point used for GDP accounting. However, the analysis is unable to account for changes in inventories, so the estimate of clean-energy investment is for fixed asset investment in the sectors.

The analysis does not explicitly account for the small and declining role of imports in producing clean-energy goods and services. This means that the results slightly overstate the contribution to GDP but understate the contribution to growth.

For example, one of the most important import dependencies that China has is for advanced computing chips for EVs. The value of the chips in a typical EV is $1,000 and China’s import dependency for these chips is 90%, which suggests that imported chips represent less than 3% of the value of EV production.

The estimates are likely to be conservative in some key respects. For example, Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimates “investment in the energy transition” in China in 2024 at $800bn. This estimate covers a nearly identical list of sectors to ours, but excludes manufacturing – the comparable number from our data is $600bn.

China’s National Bureau of Statistics says that the total value generated by automobile production and sales in 2023 was 11tn yuan. The estimate in this analysis for the value of EV sales in 2023 is 2.3tn yuan, or 20% of the total value of the industry, when EVs already made up 31% of vehicle production and the average selling prices for EVs was slightly higher than for internal combustion engine vehicles.

The post Analysis: Clean energy drove more than a third of China’s GDP growth in 2025 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Clean energy drove more than a third of China’s GDP growth in 2025

Greenhouse Gases

分析:清洁能源2025年为中国GDP增长贡献超过三分之一

2025年,太阳能、电动汽车及其他清洁能源技术对中国经济增长的贡献已超过三分之一,并拉动超过九成的投资增长。

中国清洁能源行业产值在2025年达到创纪录的15.4万亿元人民币(约合2.1万亿美元),约占国内生产总值(GDP)的11.4%,该数字相当于巴西或加拿大的经济规模。

Carbon Brief基于官方数字、行业数据及分析师报告进行的最新分析显示,2022年至2025年间,中国清洁能源行业的实际规模几乎翻了一番;若将其视为一个独立经济体,其规模可位列全球第八。

该分析的其他主要成果包括:

- 清洁能源行业支撑中国实现了“5%左右”的GDP增长目标,若排除清洁能源行业,2025年GDP实际增速仅为3.5%。

- 清洁能源产业的扩张速度持续快于整体经济,其年增长率从2024年的12%提升至2025年的18%。

- 电动汽车、电池和光伏“新三样”仍是中国清洁能源经济贡献的核心,创造了约三分之二的增加值,并吸纳了一半以上的行业投资。

- 2025年,中国在清洁能源领域的投资达7.2万亿元人民币(约1万亿美元),约为同期化石燃料开采与煤电投资(2600亿美元)的四倍。

- 尽管2025年清洁能源技术出口保持了快速增长,但对中国企业而言,国内市场在价值规模上仍显著大于出口市场。

这些投向清洁能源制造业的资金,代表着对中国乃至全球能源转型的重大押注,也为政府和企业保持这一发展势头提供了动力。

然而,未来的长期走势仍然存在不确定性,尤其是在太阳能领域。受136号文件下的新定价机制影响,太阳能发电装机增速已有所放缓,而中央政府设定的相关目标也明显低于近几年的实际扩张水平。

如果放缓趋势持续下去,这些产业或将从经济增长的驱动力转变为拖累因素,同时加剧工业领域的“产能过剩”问题,并进一步恶化国际贸易摩擦。

但即便中央政府对清洁能源未来五年的目标设定较为谨慎,地方政府和国有企业的规划与投资力度,仍有可能推动清洁能源产业继续实现显著增长。

本文在此前对2023年和2024年清洁能源经济贡献分析的基础上进行了更新。

清洁能源行业表现优于整体经济

中国的清洁能源经济持续高速增长,远超整体经济增速。这意味着它对年度经济增长的贡献尤为显著。

下图显示,2025年,清洁能源技术贡献了中国超过三分之一的GDP增量,并推动了超过90%的新增投资增长。

2022年,中国清洁能源经济规模约为8.4万亿元人民币(1.2万亿美元)。到2025年,这一规模几乎翻了一番,达到15.4万亿元人民币(2.1万亿美元)。

这一体量相当于巴西或加拿大的经济总量,使中国的清洁能源产业堪比全球第八大经济体,产值约为世界第四大经济体印度经济总量的一般,也大致相当于美国加利福尼亚州经济规模的一半。

由于清洁能源产业持续跑赢整体经济,其在中国经济中的占比也在不断上升,从2022年占中国GDP的7.3%上升至2025年的11.4%。

如果没有清洁能源行业,中国2025年的GDP增速将仅为3.5%,因此,在经济稳定增长为中国首要目标之一的2025年,清洁能源做出了至关重要的贡献。

下表按行业和活动进行了详细分类。

电动汽车和电池是GDP增长的最大驱动力

2024年,电动汽车和太阳能是最大的增长驱动力。而到了2025年,电动汽车和电池则占据了主导地位,合计贡献了44%的经济效益,以及清洁能源行业一半以上的增长。这主要得益于产出和投资的同步强劲增长。

在未剔除通胀因素的名义GDP口径下,电动汽车的贡献甚至更为突出。这是因为电动汽车价格同比保持相对稳定,而整体经济仍处于通缩环境中。同时,电池制造投资在2024年下滑后于2025年出现反弹。

下图展示了电动汽车和电池的主要贡献,既反映了清洁能源经济的整体规模,也显示了各子行业对年度增量的具体贡献情况。

第二大子行业是清洁能源发电、输电和储能,在2025年占清洁能源对GDP贡献的40%,并贡献了清洁能源产业当年约30%的增长。

在电力领域内部,最主要的增长动力来自风电和太阳能发电装机投资的扩大,以及风电和太阳能发电量的增长;其次是太阳能设备及材料的出口。

作为2022–2023年的重要增长引擎,太阳能组件产业链投资在2025年连续第二年下降,这与政府遏制产能过剩和行业“非理性”价格竞争的政策导向一致。

此外,铁路运输约占清洁能源行业总经济产出的12%,但其同比增长相对温和,2025年其营业收入增长3%,投资增长6%。

需要指出的是,国际能源署(IEA)在其《世界能源投资报告》中估计,中国2025年清洁能源投资为 6270亿美元,而化石能源投资为 2570亿美元。

在采用与IEA一致的行业口径进行测算时,本研究对2025年中国清洁能源投资的估计为 4300亿美元,低于IEA的数值。而本文中所呈现的1万亿美元清洁能源投资总规模,并非源于更激进的单项假设,而是由于纳入了更为广泛的产业和活动范围,超出了IEA报告所覆盖的口径。

电动汽车和电池

2025年,电动汽车与动力电池成为中国清洁能源经济中最大的贡献部分,约占清洁能源行业总值的44%。

其中,纯电动汽车和插电式混合动力汽车的生产在价值规模和当年增长贡献两方面均居首位,产量同比增长29%。排在其后的是电动汽车制造领域的投资,在2024年增速放缓后,2025年投资规模同比增长 18%

电池制造投资在2024年出现下滑后也迎来反弹,这主要得益于电池新技术的涌现以及国内外市场的强劲需求。电池制造投资同比增长35%,达到2770亿元人民币。

到2025年底,电动汽车在全国汽车保有量中的占比预计达到12%,高于一年前的 9%,而在五年前这一比例还不足 2%。

在新车销售中,电动汽车占比进一步提升至 48%,高于2024年的 41%,其中乘用车电动汽车渗透率已突破50%。2025年11月,电动汽车在当月汽车总销量中的占比更是首次突破 60%,并持续成为拉动整体汽车销量增长的主要动力,如下图所示。

电动卡车市场取得突破性进展,其市场份额从2024年前九个月的8%,增长至2025年同期的23%。

政府对电动汽车的政策支持仍在持续,例如,一项最新政策提出,未来三年内充电基础设施规模将接近翻倍,以支撑电动汽车进一步普及。

在电动汽车市场中,出口增速快于国内销售增速,但整体销售仍以国内市场为主。2025年,中国电动汽车产量达到 1660万辆,同比增长 29%。其中,出口约340万辆,占总产量的 21%,但同比增速高达 86%。中国电动汽车的主要出口目的地包括西欧、中东和拉丁美洲。

电池出口额同样实现快速增长,同比上升 41%,成为推动GDP增长的第三大动力来源。电池出口主要流向西欧、北美和东南亚市场。

与许多清洁能源技术价格呈现的通缩趋势不同,2025年电动汽车的平均售价保持稳定,新车型在折扣后的平均加个甚至略有上涨。在全社会工业品出厂价格同比下降 2.6% 的背景下,这意味着电动汽车产业对名义GDP增长的贡献尤为突出。相比之下,电池价格仍延续下降趋势。

清洁能源发电

2025年,太阳能发电行业贡献了清洁能源产业总值的19%,为国民经济创造2.9万亿元人民币(约合410亿美元)的价值。

其中,新建太阳能发电厂的投资额达1.2万亿元人民币(约合1600亿美元),是清洁能源发电板块最大的驱动力;其次是太阳能技术出口额和太阳能发电本身创造的电力价值。太阳能制造业投资在2023年产能扩张浪潮结束之后持续下降,至0.5万亿元人民币(约合720亿美元),同比下降23%。

2025年,中国风电和太阳能发电新增装机容量再创新高。全国新增太阳能发电装机315吉瓦,新增风电装机119吉瓦,其中太阳能发电装机容量比全球其他地区总和还要多,而风电装机容量更是后者两倍之多。

在电力投资结构中,清洁能源占发电领域投资的90%,其中光伏一项就占到约50%。在此推动下,非化石能源发电量占全国总发电量的比重提升至42%,高于2024年的 39%。

不过,新出台的新能源定价政策以及相对谨慎的装机目标,也为这一轮增长能否持续带来了不确定性。在136号文件新政策框架下,新建风电和太阳能发电项目需要在电力市场中与既有煤电直接进行价格竞争,而在若干关键制度设计上仍处于相对不利的位置。

与此同时,电力市场本身仍处于建设和发展阶段,这也带来了投资的不确定性。

太阳能发电投资同比增长6%,但期间波动剧烈。开发商赶在新定价政策于6月生效前加速完成项目,第三季度放缓后,在年底再次赶工,以赶在“十四五”规划期内达成目标。

总体来看,太阳能产业整体投资规模与上一年大致持平:制造环节投资下降,被发电侧的增长所抵消。这在一定程度上支撑了制造产能利用率,也符合政府遏制行业“无序竞争”和价格内卷的政策目标。

2025年底,中国太阳能制造产能预计已达到每年1200吉瓦,远超2025年全球新增装机容量约650吉瓦的水平。目前,中国太阳能产业制造能力已显著超过全球市场吸收能力,激烈竞争导致行业盈利水平处于历史低位。

自2024年中期以来,中国的政策制定者已开始正面应对这一问题,包括警示“内卷式竞争”、出台监管措施,并召开行业会议向企业施压。相关举措已初见成效,2025年第三季度行业亏损有所收窄。

2025年,太阳能电池板及组件出口量再创历史新高,同比增长19%。其中,电池片和硅片出口量分别快速增长94%和52%,而电池板出口量仅增长4%。

这反映出,在关税压力上升、更多国家加快本土制造布局的背景下,全球太阳能供应链正日益趋向多元化。然而,由于平均出口价格下跌,以及出口产品结构从成品电池板向上游中间产品转移,出口名义价值反而同比下降了8%。

2025年,水能、风能和核能合计贡献了清洁能源行业总产值的约15%,为中国GDP带来约2.2万亿元人民币(3100亿美元)的增加值。

其中近三分之二(1.3万亿元人民币,1800亿美元)来自水电、风电和核电的发电价值,其余部分则来自新建发电项目的投资。

从发电量增速来看,2025年太阳能发电量增长33%,风电增长13%,水电增长3%,核电增长8%。

在发电投资领域,太阳能仍是价值规模最大的板块(如下图所示),但风电项目在2025年首次成为投资增长的最大贡献者,这是自2020年以来风电投资首次在增量上超过太阳能。

特别是海上风电装机投资如预期般反弹,在2024年大幅下降后,2025年实现翻倍增长,成为清洁电力投资中的一个亮点。

核电项目投资持续增长,但总体规模仍然较小,2025年投资额约为170亿元人民币。常规水电投资则延续下行趋势,同比下降7%。

储能和电网

2025年,输电和储能占清洁能源行业总产值的6%,规模达到1万亿元人民币(1400亿美元)。

其中,电网投资2025年增长了约6%,达到900亿美元。储能投资(涵盖抽水蓄能、新型储能和氢气制备)2025年达到约500亿美元。

新型储能投资同比增长幅度达50%,电解槽投资也增长了30%。受清洁能源发电快速增长推动,清洁能源输送规模预计增长13%。

中国电力储能总装机容量超过213吉瓦,其中新型储能容量超过145吉瓦,抽水蓄能容量为69吉瓦。预计2025年中国新增约66吉瓦新型储能装机容量,同比增长52%,占全球新增装机容量的40%以上。

值得注意的是,下半年新型储能装机增速加快,达43吉瓦,而上半年新增装机容量为23吉瓦。

在政策层面,136号文件规定在5月后取消了新能源配套储能的强制要求,曾一度导致新型储能市场增速放缓,但这一影响很快被“市场驱动型增长”所取代。省级电力现货市场的推进、分时电价机制以及太阳能弃光率上升,共同改善了储能项目的经济性。

到2025年底,中国前五大太阳能制造商均进入了新型储能市场,标志着行业战略的重要转变。

与此同时,抽水蓄能投资保持增长,仅2025年上半年,就有15吉瓦的项目获批,新增3吉瓦抽水蓄能投入运营。

铁路

铁路运输占清洁能源行业GDP的12%,其中客货运输收入是最主要的价值来源。行业增长主要来自铁路基础设施投资,2025年同比增长6%。

交通电气化不仅限于电动汽车,铁路客运、货运及相关投资规模也持续增长。2025年,中国高铁总里程约达5万公里,占全球高速铁路总里程的70%以上。

节能服务

2025年,节能服务投资强劲反弹。以大型节能服务公司(ESCO)的产值衡量,市场规模同比增长17%,恢复至2016-2020年期间的增长水平。

行业产值也已恢复到2021年的峰值水平,这表明在经历三年低迷后,行业已明显回暖。

行业预测显示,节能服务行业年产值有望在2030年达到1万亿元人民币,而行业经历低迷前曾预期这一目标将在2025年实现。

中国已发展成为全球最大的节能服务公司市场。其投资高度集中于建筑领域,约占业务总量的50%;工业应用占21%,而能源供应、需求侧灵活性与储能相关业务合计约占16%。

中国清洁能源布局的影响

中国持续向清洁能源制造业投入数千亿美元,代表着对全球能源持续转型的一项规模巨大的经济与金融押注。

除本文所涵盖的国内投资外,中国企业还在海外制造业领域展开了大规模投资布局,进一步加深了这一押注的全球化属性。

在十四五规划期间,清洁能源产业对中国实现经济增长目标起到了关键作用,在2023年、2024年和2025年分别贡献了约40%、25%和37%的GDP增长。

然而,长期的发展前景仍存在不确定性,尤其是在太阳能发电领域。136文件下新的可再生能源发电定价机制已导致短期投资增速放缓,并显著增加了市场不确定性;与此同时,中央政府设定的清洁电力新增装机目标也相对保守,远低于当前实际增长水平。

2025年下半年,太阳能发电和光伏制造领域的投资均出现下降,尽管从全年来看,发电投资保持了增长。这反映出在当前电力市场制度仍偏向煤电的框架下,清洁能源产业面临结构性风险。

清洁能源技术价格下降幅度显著,以致在未来核算GDP时,这些行业对实际GDP(经通胀或通缩调整后的GDP)的贡献可能会被向下修正。

尽管如此,清洁能源产业在宏观经济中的关键地位,本身就构成了维持这一轮清洁能源发展势头的强烈政策和经济动机。如果国内市场增长出现明显放缓,不仅可能削弱遏制产能过剩的努力,或将迫使更多产能转向出口,从而加剧国际贸易摩擦。

能源与清洁空气研究中心近期针对中国气候与能源领域专家开展的一项调查显示,多数专家认为,在经济和地缘政治挑战加剧的背景下,“双碳目标”及其所依托的清洁能源产业,只会变得更加重要。

地方政府和国企同样将深刻影响该行业的发展前景。在十四五期间,正是地方政府和国企的积极推进,促成了规模空前、且显著超出预期的“风光大基地”建设。

同时,各省在落实新电力市场机制和可再生能源购电合同安排方面拥有较大的自主空间,因此,将于今年发布的十五五规划,将成为决定清洁能源产业中长期走势的关键。

关于数据

本文分析尽可能采用已公布的投资与销售数据。若数据不可得,则依据实际数量(如装机容量、汽车销量等)结合单位成本或价格进行估算。

为衡量实际增长贡献,相关数据已按2022-2023年价格进行通胀或通缩调整。全部计算过程与数据来源详见附表。

估算范围涵盖清洁能源技术对上游原材料(如金属、化学品)的需求贡献。

该方法不仅能够反映清洁能源行业对整体经济活动的拉动作用,也能提现其对相关产业活动的带动作用,因此可适用于估算:若该行业未曾增长,经济增速可能降低多少。

为避免重复计算,仅计入价值链中不重叠的环节。例如,电动汽车的生产产值与储能电池的投资额均予计入,但不包含作为上述活动中间投入的、面向国内市场的电池生产价值。

同理,国内市场的太阳能电池板产值已包含在中国光伏发电装机容量的价值中,故不重复统计;然而,太阳能电池板及电池的出口价值则纳入计算。

2025年,两项关键投资指标出现明显背离:据报道,固定资产投资下降3.8%,为35年来首次下滑;而同期资本形成总额虽增速放缓至近年最低,但仍保持2%的正增长。

本研究采用资本形成总额作为投资衡量指标,因其是GDP的组成部分。但由于无法全面追踪库存变动,对清洁能源投资的估算仍基于各行业的固定资产投资数据。

本分析未专门考虑进口因素——其在清洁能源产品与服务生产中所占比例较小且持续下降。这意味着结果可能略微高估对GDP的贡献,但同时低估了对GDP增量的贡献。

例如,中国在电动汽车中对高端计算芯片仍存在较高的进口依赖。一辆典型电动汽车的芯片价值约1000美元,而该类芯片的进口依赖度高达90%,但这仍进展整车生产价值的3%以内。

在某些方面,本研究的估算可能相对保守。例如,彭博新能源财经(BNEF)估计2024年中国“能源转型投资”规模约为8000亿美元。彭博估算的行业覆盖范围与本分析大致相当,但未包含制造业产值。在相同口径下,本研究对应的投资规模约为6000亿美元。

根据中国国家统计局数据,2023年全国汽车产业总产值与销售额合计约11万亿元人民币。本分析估算,同年电动汽车销售额约为2.3万亿元,约占行业总值的20%。当时,电动汽车产量已占汽车总产量的31%,且其平均售价略高于传统燃油汽车。

The post 分析:清洁能源2025年为中国GDP增长贡献超过三分之一 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Five key climate and energy announcements in India’s budget for 2026

On 1 February, India’s finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman unveiled the government’s budget for 2026, which included a new $2.2bn funding push for carbon capture technologies.

In the absence of its new international climate pledge under the Paris Agreement, the budget offers a glimpse into the key climate and energy security priorities of the world’s third-largest emitter, amid increasing geopolitical tensions and trade challenges.

While Sitharaman’s budget speech did not mention climate change directly, she said: “Today, we face an external environment in which trade and multilateralism are imperilled and access to resources and supply chains are disrupted.”

Sitharaman emphasised that “new technologies are transforming production systems while sharply increasing demands on water, energy and critical minerals”.

The budget sets out: support for the mining and processing of critical minerals and rare earths; import duty exemptions for nuclear power equipment; and support for renewables, particularly rooftop solar.

However, unlike in some previous years, the 2026 budget does not include specific climate adaptation measures.

Below, Carbon Brief runs through five key climate- and energy-focused announcements from the budget.

- Carbon capture, utilisation and storage

- Critical minerals and rare earth ‘corridors’

- Nuclear energy

- Renewables

- Adaptation

Carbon capture, utilisation and storage

The biggest climate-related budget announcement was $2.2bn to support carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) technologies in India over the next 5 years.

These are technologies that capture carbon dioxide (CO2) as it is released, then use or store it underground or under the sea.

This funding is aimed at decarbonising five of India’s high-emitting industrial sectors – power, steel, cement, refineries and chemicals. These sectors are “staring at the risk” of coming under the EU’s carbon adjustment mechanism (CBAM), even after a recent EU-India trade deal, according to Sitharaman.

The funding is meant to align with a roadmap released last year that sees CCUS as a “core technological pillar” of India’s 2070 net-zero strategy, particularly for “decarbonising sectors where viable alternatives are limited”, notes the government’s roadmap.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) sixth assessment report, however, the need for CCUS to mitigate industrial emissions “may be overestimated”, compared to measures such as energy and material efficiency and electrification.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Dr Vikram Vishal, a professor of earth sciences at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay (IIT-B),, describes the budget move as a “big welcome step for industrial decarbonisation and India’s net-zero ambitions as a whole”.

Vishal says that the funding could go towards getting “big demonstration plants to near-commercial plants” that could entail even bigger investments in the future.

He tells Carbon Brief:

“India is blessed with both onshore and offshore availability for carbon storage. But while utilisation exists, storage has not happened, per se, even at a decent scale. We [would] need to build transportation infrastructure from the point source of capture at scale, on land and offshore. While offshore storage is very low risk, onshore presents a closer proximity to emission sources.”

However, that could also mean closer proximity to densely populated or protected areas.

Vishal adds that India has a very large theoretical storage potential, even a quarter of which would allow for up to 150bn tonnes of CO2 to be stored. This could sustain CCUS for hundreds of years, Vishal says, adding: “And by that time, the energy transition would have happened, right?”

Critical minerals and rare-earth ‘corridors’

Mining, sourcing and processing “critical minerals” and rare earths is another key area of India’s 2026 budget.

It proposes establishing “dedicated rare-earth corridors” in the “mineral-rich” coastal states of Odisha, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu to “promote mining, processing, research and manufacturing”. These corridors are intended to complement a $815m rare-earth permanent-magnet scheme announced in November.

In addition, the budget supports “incentivising prospecting and exploration” for rare-earth minerals, such as monazite, as well as others that the government wants to include in its list of “critical minerals”.

Last week, for instance, India classified coking coal – which is predominantly used in making steel – as a “critical and strategic mineral”, removing regulatory measures such as the need to consult affected communities before developing new mines.

Sehr Raheja, programme officer at New Delhi thinktank Centre for Science Environment, tells Carbon Brief that “moving up the critical-minerals value chain” is “increasingly essential” for the energy transition in developing countries.

She adds that some of the measures announced in India’s budget “point in that direction”, explaining:

“Globally, developing countries often stay stuck in the extraction stages of value chains and capture the least value. While duty exemptions for critical mineral processing and battery manufacturing signal intent to build domestic manufacturing capacity, the extent to which these new efforts deliver sustained value will only become apparent over time.”

Rahul Basu, research director at the Goa Foundation, which advocates for “intergenerational equity” in mining, tells Carbon Brief:

“Rare earths are not particularly rare. What is difficult is separating and refining them. China imports ore from around the world, including [the] US. Their competitive advantage lies in processing, including the ability to tolerate high pollution levels.

“India should perfect the processing technology with imported ores first. It is the critical piece. Not mining. We seem to want to mine the same beaches that are already seeing sea-level rise.”

Nuclear energy

The Indian government has also lifted customs duties on imports of nuclear power equipment within the 2026 budget.

Under the changes, equipment for all nuclear power plants will not be subject to customs duties until 2035, irrespective of capacity.

The announcement follows India enacting a landmark new nuclear act, dubbed the “Shanti” act, in December 2025. This seeks to privatise and invite foreign participation in the country’s nuclear energy sector, which has been largely state-run for decades and has a long history of public protests over safety and land-acquisition concerns.

The Shanti act – which is an acronym for “sustainable harnessing and advancement of nuclear energy for transforming India” – aims to help India increase its nuclear capacity tenfold to 100 gigawatts (GW) by 2047.

This coincides with 100 years since India’s independence and is “the year India aims to attain developed-nation status”, according to prime minister Narendra Modi.

Renewables

Support for renewables in India’s budget this year is significant, but “uneven”, experts tell Carbon Brief.

Allocations to India’s Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) grew by 24% to a “record high” in the 2026 budget, with the bulk going to the prime minister’s flagship rooftop solar scheme. The government also cut import duties on lithium-ion cells for battery storage systems, as well as on inputs for solar-panel glass manufacturing.

However, Vibhuti Garg, South Asia director for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, tells Carbon Brief that spending on wind energy and – “more critically” – on transmission and energy storage has either “stagnated or declined” this year.

Garg says grid infrastructure is “fundamental” to renewable expansion. She explains:

“Transmission infrastructure and storage are fundamental to integrating higher shares of renewable energy into the grid. As renewable penetration rises, these elements become not optional but indispensable, and the current level of support falls short of what is required.”

Adaptation

The budget does not announce any specific adaptation measures or schemes, although it does mention a plan to develop and rejuvenate reservoirs and water bodies and to “strengthen” fisheries value chains in coastal areas.

The budget does not mention or include measures related to heat stress or its impact on productivity and workers in sectors such as agriculture.

According to India’s national economic survey tabled ahead of the budget, adaptation and “resilience-related” domestic spending “surged” from 3.7% of the country’s GDP in 2016-17 to 5.6% in 2022-23.

Yet, unlike earlier budgets, allocations to and expenditure from India’s National Adaptation Fund for Climate Change are not separately visible in the 2026 document.

Harjeet Singh, climate adaptation expert and founding director at the Satat Sampada Climate Foundation, tells Carbon Brief that this budget was a “missed opportunity” and a response “not commensurate to the needs [for adaptation] on [the] ground or investment at the scale of crisis that we are facing”.

Singh adds that it fails to recognise the “huge” economic impacts already being felt in India. He says:

“If a budget doesn’t recognise how climate change is already eroding India’s development – causing huge economic losses – and is going to affect our GDP growth, it means that you aren’t really acting, or nudging states to do more.

“It was a missed opportunity to tell the world that we do see adaptation as a problem and we are acting on it, but we also need international cooperation.”

The post Five key climate and energy announcements in India’s budget for 2026 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Five key climate and energy announcements in India’s budget for 2026

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits