Estimating Earth’s climate sensitivity, the global average warming from doubling CO2 above pre-industrial levels, is an urgent task as it governs how much the world will warm from fossil-fuel emissions.

Recent work has essentially ruled out low values of climate sensitivity below about 2C, but how much do we know about high values of climate sensitivity?

There is an active debate about the likely upper bound of climate sensitivity, which informs the worst-case projections of warming over the coming decades.

One way to narrow this down is to study the major climate changes of Earth’s past seen in palaeoclimate “proxy data”. These records are scattered across the planet, found in everything from ice cores and ocean sediments to tree rings and coral reefs.

Combining proxy data with climate models helps scientists understand what past changes were caused by natural fluctuations in CO2 and what changes we can expect from human-caused CO2 increases in the future.

In our new study, published in Science Advances, we find that the Last Glacial Maximum – a period of extensive ice cover about 21,000 years ago – provides even stronger evidence for modern-day climate sensitivity than previously thought.

Our estimates suggest a central estimate of “equilibrium” climate sensitivity of 2.9C, with a very likely range of 2.1-4.1C.

This is around a 30% narrowing of the 2.0-5.0C range in the latest assessment from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Our findings give us more confidence that very high climate sensitivity is unlikely. They also support the IPCC’s central estimate for climate sensitivity of around 3.0C and lower estimate of 2.0C, confirming that warming would still be severe if we do not reduce fossil-fuel emissions.

Progress in climate sensitivity

For many years, the estimated range for equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS) remained stubbornly wide.

After the landmark Charney report established a “consensus” position from a study group convened by the US National Research Council back in 1979, many IPCC assessments over several decades were unable to narrow it further.

This is illustrated in the chart below, which shows the Charney report estimated range for ECS (grey bar) on the left, followed by each IPCC report in sequence, from the first in 1990 (“FAR”, light blue) through to the most recent AR6 range on the right (red). Central estimates are shown with a dot, where available. The coloured bars indicate the estimated likely range for ECS and very likely ranges are marked with whiskers.

Estimates of ECS published in successive IPCC assessments since the Charney report in 1979. Dots show central estimates. The coloured bars show the likely range and the very likely range is given by whiskers. Chart by Carbon Brief

Ahead of the IPCC’s sixth assessment report (AR6), a four-year project from an international team of scientists made a significant advance.

The resulting paper by Prof Steven Sherwood, Dr Mark Webb and colleagues, published in the Review of Geophysics in 2020, formally combined multiple lines of evidence from observed data to improve understanding of the climate “feedbacks” that can amplify or dampen surface warming. The paper played a key role in the narrower ECS range in AR6 (red bar in chart above) – particularly in raising the lower bound to 2.0C and setting the upper bound at 5.0C.

However, observed data from recent warming are not as useful for constraining the upper end of ECS estimates. This is because climate feedbacks – especially how warming affects cloud properties that either enhance or reduce their overall cooling effect – depend on spatial patterns of temperature change. Climate scientists have dubbed this phenomenon the “pattern effect”.

Pattern effects

Temperature patterns over recent decades differ substantially from what we expect in the long-term. This means that climate feedbacks are likely to change in the future too, making observed warming a relatively poor predictor of how high climate sensitivity could be.

This is where palaeoclimate data comes in. The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) has been touted as the best evidence for or against high values of climate sensitivity. By estimating how much colder the Earth was when CO2 levels were so much lower during the LGM, scientists can predict how much warmer the Earth would be with higher CO2 levels decades from now.

However, doing so requires isolating how much of the LGM cooling came from lower CO2 and correcting for how the climate’s sensitivity to CO2 differs between the cold LGM and the warm modern-day climate. Prior to our study, no one had quantified the impact of temperature patterns on climate sensitivity in the palaeoclimate record.

Traditionally, the additional cooling effect of the vast LGM ice sheets, which covered much of Canada and northern Eurasia, has been estimated from the amount of sunlight they directly reflect. But the ice sheets also caused the nearby northern Pacific and Atlantic oceans to cool and produce more low clouds, amplifying global cooling by reflecting even more sunlight. This ocean cooling is illustrated by the dark blue shading in the left-hand map below.

By linking these adjacent cloud changes to the ice sheets, we found that relatively more of the LGM cooling was caused by the ice sheets and relatively less came from the lowered CO2.

Importantly, these amplifying cloud feedbacks are unique to the climate during the ice age and, therefore, do not apply to modern CO2-driven warming that will not have similarly large ice-sheet changes.

As a result, the amount of cooling from lower CO2 at the LGM is not consistent with very high values of modern-day climate sensitivity above around 4C.

Accounting for differences between the LGM and modern climates allows us to lower the upper end of climate sensitivity estimates, representing a major shift in how palaeoclimate data is used to inform our future.

Combining palaeoclimate data with climate models

Quantifying the climate differences mentioned above for the LGM requires estimating temperature patterns and climate feedbacks from 21,000 years ago.

An obvious challenge is that our instrumental temperature records span only centuries and our satellite observations of clouds span only decades. Fortunately, there have been two major advances in recent years that allowed us to quantify the pattern effects from the distant past.

First, palaeoclimate data assimilation is a recently developed method that combines climate model simulations with proxy data, producing globally complete reconstructions of surface temperatures during the LGM. However, there are still major uncertainties in this method. Various groups have recently reconstructed the ice age, finding somewhat different temperature patterns. To assess this uncertainty, we use four available reconstructions.

Second, we use these reconstructed surface temperatures in global atmosphere models to estimate climate feedbacks during the LGM and compare them to feedbacks expected from CO2 doubling. Because different models produce different climate feedbacks – even when given the same reconstructed surface temperatures – we assess this feedback uncertainty using five different atmosphere models.

Despite the uncertainties, a consistent story emerged. Climate feedbacks strongly amplified LGM temperature changes, much more so than climate feedbacks under modern-day warming from CO2 alone. We traced these differences primarily to cloud feedbacks in the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans where the patterns of temperature change strongly differ between the LGM – due to the presence of large ice sheets – and future warming from CO2.

At first glance, the extra amplifying feedbacks of the LGM could appear to suggest that climate sensitivity is higher than we thought. A recent study led by Dr James Hansen, former director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, reported that some of the same reconstructions used here are consistent with a modern-day climate sensitivity of around 4.8C.

However, that interpretation is reversed when we recognise that those amplifying feedbacks are unique to the ice age climate and do not apply to the modern-day climate.

The result is that modern-day climate sensitivity, as estimated from the LGM, is actually lower than has been reported by studies such as Hansen’s that have not accounted for the unique effect of ice sheets on climate feedbacks.

Our findings also challenge a common assumption that warmer climates are more sensitive than colder climates. While that assumption appears likely to be true for climates warmer than today, it appears to be false for climates colder than today when the effect of ice sheets on temperature patterns and feedbacks is included.

Implications for future warming

The LGM, after accounting for how temperature patterns impact climate feedbacks, ends up being an even stronger constraint on modern-day climate sensitivity – especially the upper bound.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that considering pattern effects has helped constrain climate sensitivity instead of adding to its uncertainty for modern-day climate.

Given the importance of combining multiple lines of evidence, we use the community framework from the Sherwood, Webb et al (2020) study, updated to include our estimate of how climate feedbacks differ between the LGM and modern-day warming.

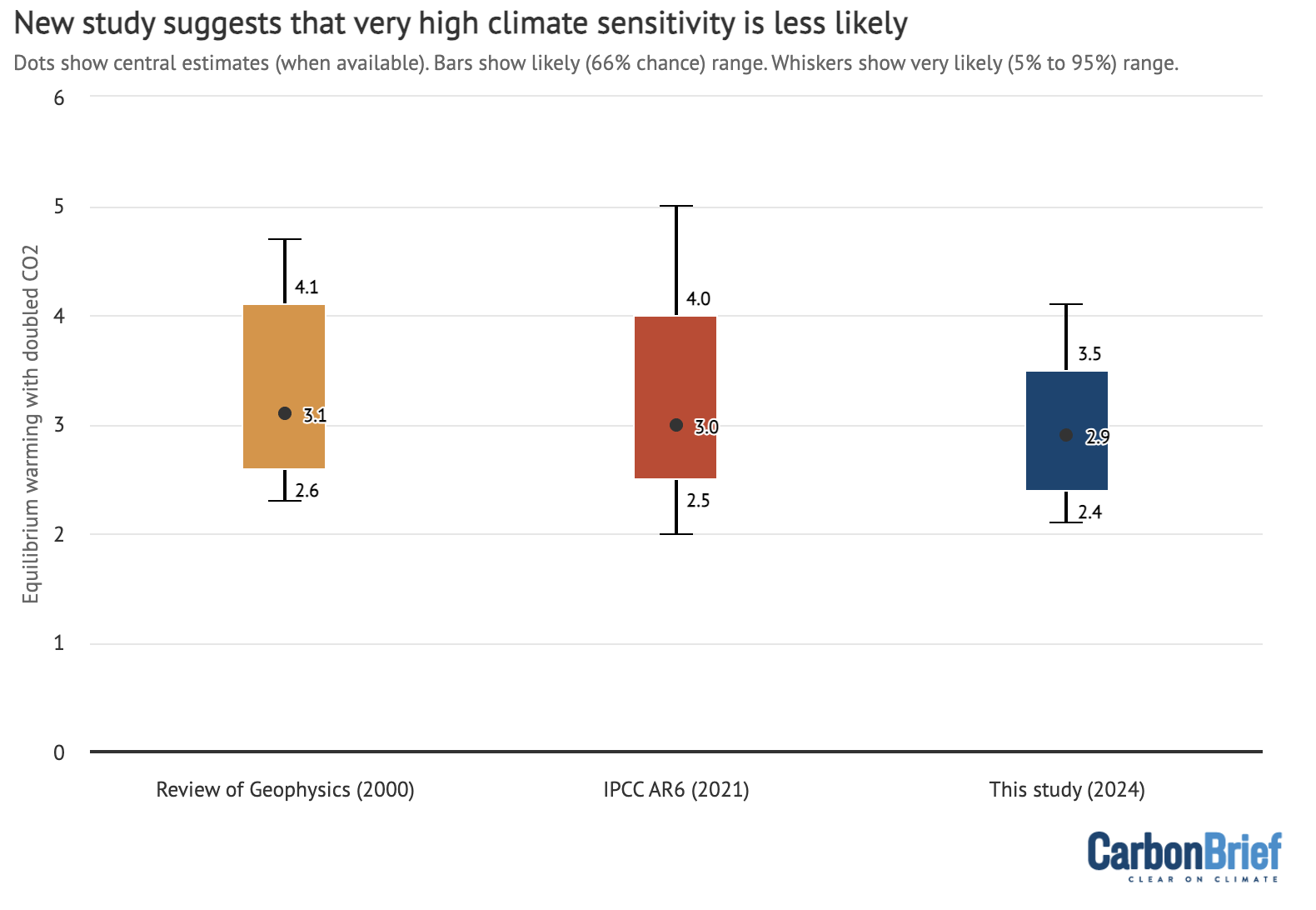

As the chart below shows, our revised best estimate of climate sensitivity (blue) becomes 2.9C with a very likely range of 2.1-4.1C, a substantial narrowing of uncertainty by reducing the upper bound.

In contrast, the IPCC AR6 very likely range was 2.0-5.0C with a best estimate of 3C (red), while the Sherwood, Webb et al (2020) study reported 2.3-4.7C and central estimate of 3.1C (yellow).

Modern-day ECS estimates from recent assessments, including the Sherwood, Webb et al (2020 study (yellow), IPCC AR6 (red) and this study (blue). Dots show central estimates. The coloured bars show the likely range and the very likely range is given by whiskers. Chart by Carbon Brief based on data provided by V Cooper and K Armour

While the lower bound and central estimates are mostly unchanged, our findings reduce the upper bound by approximately 1C.

Based on the modelled relationship between climate sensitivity and future warming, lowering the upper bound on climate sensitivity from 5C to 4.1C translates to a reduction of 0.4-0.8C in the upper end of global warming estimates by 2100 (the range reflects uncertainty in future emissions). In other words, this is a substantial reduction in the likelihood of extremely high warming.

Our results for the LGM show that temperature patterns and their effects on climate feedbacks must be accounted for when using past climates to estimate modern-day climate sensitivity.

Spatial reconstructions of past climates are a necessity and there are opportunities for further progress in constraining climate sensitivity by analysing temperature patterns and feedbacks in other past climates.

The post Guest post: Ice-age analysis suggests worst-case global warming is less likely appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: Ice-age analysis suggests worst-case global warming is less likely

Climate Change

Satellites Reveal New Climate Threat to Emperor Penguins

Ice loss in the Antarctic Ocean may be killing the sea birds during their molting season.

Each year for millennia, emperor penguins have molted on coastal sea ice that remained stable until late summer—a haven during a span of several weeks when it’s dangerous for the mostly aquatic birds to enter the ocean to feed because they are regrowing their waterproof feathers.

Climate Change

States Sue to Block Trump’s ‘Anti-Science’ Vaccine Policy

Climate change helps spread vaccine-preventable diseases. But the Trump administration’s reduced vaccine schedule “throws science out the window,” and makes Americans more vulnerable to infections, state attorneys general charge in a new lawsuit.

Scientists have long warned that a warming world is likely to hasten the spread of infectious diseases, making vaccination even more critical to safeguard public health.

Climate Change

Hurricane Helene Is Headed for Georgians’ Electric Bills

A new storm recovery charge could soon hit Georgia Power customers’ bills, as climate change drives more destructive weather across the state.

Hurricane Helene may be long over, but its costs are poised to land on Georgians’ electricity bills. After the storm killed 37 people in Georgia and caused billions in damage in September 2024, Georgia Power is seeking permission from state regulators to pass recovery costs on to customers.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits