Global yields of wheat are around 10% lower now than they would have been without the influence of climate change, according to a new study.

The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, looks at data on climate change and growing conditions for wheat and other major crops around the world over the past 50 years.

It comes as heat and drought have this year been putting wheat supplies at risk in key grain-producing regions, including parts of Europe, China and Russia.

The study finds that increasingly hot and dry conditions negatively impacted yields of three of the five key crops examined.

Overall, global grain yields soared during the study period due to technological advancements, improved seeds and access to synthetic fertilisers.

But these yield setbacks have “important ramifications for prices and food security”, the study authors write.

Grain impacts

Most parts of the world have experienced “significant” yield increases in staple crops since the mid-20th century.

The new study notes that, in the past 50 years, yields increased by 69-123% for the five staple crops included in the research – wheat, maize, barley, soya beans and rice.

But crop production is increasingly threatened by climate change and extreme weather. A 2021 study projected “major shifts” in global crop productivity due to climate change within the next two decades.

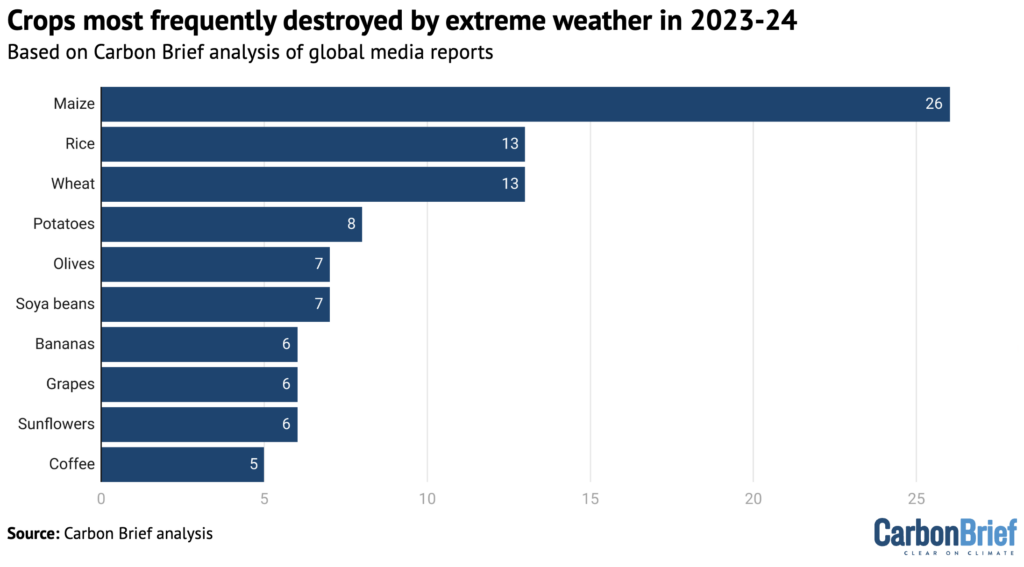

Earlier this year, Carbon Brief mapped out news stories of crops being destroyed around the world by heat, drought, floods and other weather extremes in 2023-24. Maize and wheat were the crops that appeared most frequently in these reports.

Hot and dry weather is currently threatening wheat crops in parts of China, the world’s largest wheat producer, Reuters reported this month.

In the UK, wheat crops are struggling amid the “driest start to spring in England for almost 70 years”, the Times recently reported. Farm groups say some crops are already failing, the Guardian said.

As a result, global wheat supplies are “tight”, according to Bloomberg, with price rises possible depending on weather conditions in parts of Europe, China and Russia.

Food security and prices

The study uses climate datasets, modelling and national crop statistics from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization to assess crop production and climate trends in key grain-producing countries over 1974-2023, including Argentina, Brazil, Canada, China, the EU, Russia and the US.

The researchers assess climate observations and then use crop models to calculate what yields would have been with and without these climate changes.

For example, “if it has warmed 1C over 50 years and the model says that 1C leads to 5% yield loss, we’d calculate that the warming trend caused a loss of 5%”, Prof David Lobell, the lead study author and a professor at Stanford University, tells Carbon Brief.

The study looks at two reanalysis climate datasets that include information on temperature and rainfall over the past 50 years: TerraClimate (TC) and ERA5-Land. (Reanalysis data combines observations with a modern forecasting model.)

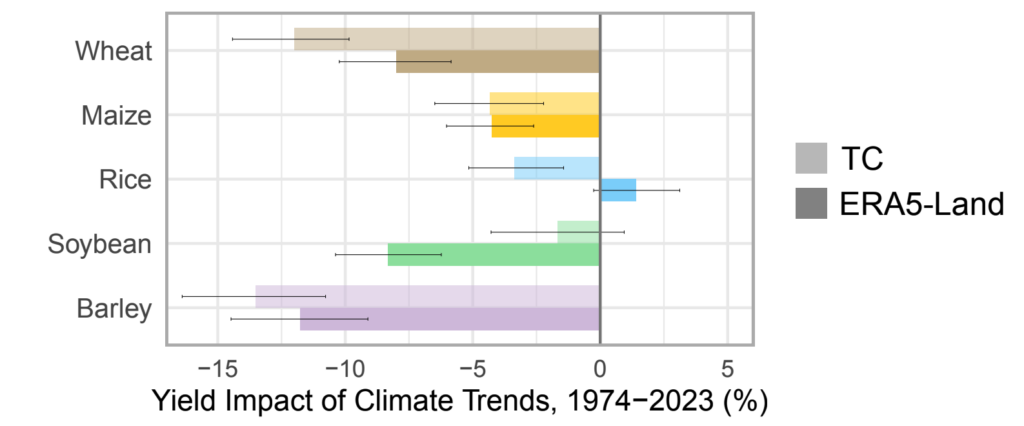

The researchers find that yields of three of the five crops are lower than they would have been without warmer temperatures and other climate impacts in the past 50 years.

Yields were lower than they otherwise would have been by 12-14% for barley, 8-12% for wheat and 4% for maize.

The impacts on soya beans were less clear as there were “significant differences” between data sources. But both datasets show a negative impact on yields, ranging from 2% to 8%.

The effects on rice yields were inconclusive, with one dataset showing a positive effect of around 1% while the other showed a negative effect of about 3%.

The chart below shows the estimated yield impacts for each crop based on the calculations from the two climate datasets.

Given soaring overall crop yields during this time, impacts of 4-13% “may seem trivial”, the researchers write. But, they say, it can have “important ramifications for prices and food security” given growing food demand, noting:

“The overall picture of the past half-century is that climate trends have led to a deterioration of growing conditions for many of the main grain-producing regions of the world.”

Water stress and heat

The study also assesses the impacts that warming and vapour pressure deficit – a key driver of plant water stress – have on crop yields.

Vapour pressure deficit is the difference between the amount of water vapour in the air and the point at which water vapour in the air becomes saturated. As air becomes warmer, it can hold more water vapour.

A high deficit can reduce plant growth and increase water stress. The models show that these effects may be the main driver of losses in grain yield, with heat having a more “indirect effect”, as higher temperatures drive water stress.

The study finds that vapour pressure deficit increased in most temperate regions in the past 50 years.

The researchers compare their data to climate modelling simulations covering the past 50 years. They find largely similar results, but notice a “significant underestimation” of vapour pressure deficit increases in temperate regions in most climate models.

Many maize-growing areas in the EU, China, Argentina and much of Africa have vapour deficit trends that “exceed even the highest trend in models”, they write.

The researchers also find that most regions experienced “rapid warming” during the study period, with the average crop-growing season now warmer than more than 80% of growing seasons 50 years ago.

The findings indicate that, in some areas, “even the coolest growing season in the present day is warmer than the warmest season that would have occurred 50 years ago”.

An exception to this is in the US and Canada, they find, with most maize and soya bean crop areas in the US experiencing lower levels of warming than other parts of the world and a “slight cooling” in wheat-growing areas of the northern Great Plains and central Canada.

(The central US has experienced a cooling trend in summer daytime temperatures since the middle of the 20th century, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. There are many theories behind this “warming hole”, which has continued despite climate change.)

CO2 greening

Dr Corey Lesk, a postdoctoral researcher at Dartmouth College who studies the impacts of climate on crops, says these findings are in line with other recent estimates. He tells Carbon Brief:

“There are some uncertainties and sensitivity to model specification here – but it’s somewhat likely climate change has already reduced crop yields in the global mean.”

The study’s “main limitation” is that it is “behind” on including certain advances in understanding how soil moisture impacts crops, Lesk adds:

“Moisture changes and CO2 [carbon dioxide] effects are the largest present uncertainties in past and future crop impacts of climate change. This paper is somewhat limited in advancing understanding on those aspects, but it’s illuminating to pause and take stock.”

The research looks at whether the benefits of CO2 increases during the past 50 years exceed the negative effects of higher levels of the greenhouse gas.

Rising CO2 levels can boost plant growth in some areas in a process called “CO2 fertilisation”. However, a 2019 study found that this “global greening” could be stalled by growing water stress.

Yield losses for wheat, maize and barley “likely exceeded” any benefits of CO2 increases in the past 50 years, the study finds.

The opposite is true for soya beans and rice, they find, with a net-positive impact of more than 4% on yields.

Climate science has “done a remarkable job of anticipating global impacts on the main grains and we should continue to rely on this science to guide policy decisions”, Lobell, the lead study author, says in a press release.

He adds that there may be “blind spots” on specialised crops, such as coffee, cocoa, oranges and olives, which “don’t have as much modelling” as key commodity crops, noting:

“All these have been seeing supply challenges and price increases. These matter less for food security, but may be more eye-catching for consumers who might not otherwise care about climate change.”

The post Global wheat yields would be ‘10%’ higher without climate change appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Global wheat yields would be ‘10%’ higher without climate change

Climate Change

New summit in Colombia seeks to revive stalled UN talks on fossil fuel transition

A landmark conference hosted by Colombia and the Netherlands will aim to lay the foundations for renewed talks on transitioning away from fossil fuels at COP31, though organisers say it remains unclear what concrete outcomes it will deliver.

The First Conference on the Transition Away from Fossil Fuels will take place in April in the city of Santa Marta, on Colombia’s Caribbean coast, where first-moving countries, states and cities will seek to restart last year’s stalled push for a global roadmap away from coal, oil and gas.

Bastiaan Hassing, head of international climate policy for the Dutch government, told an online briefing last week that the “most obvious” impact of the conference would be for its hosts to report back to the UN climate summit on what was agreed in Santa Marta.

“Ideally, but this is also more complicated, we discuss with each other (at COP) what next steps we could take in the implementation, for instance, of paragraph 28 of the COP decision in Dubai, which talks about the global transition away from fossil fuels,” Hassings said.

He noted that there are many options for how the conference can influence UN talks on implementing the global transition away from fossil fuels, but the exact possibilities would depend on the outcome of the talks. “Rest assured that we will be looking into this,” he added.

At last year’s COP30, a bloc of 80 countries, including small island states, as well as some Latin American, European, and African countries, called for the creation of a roadmap to transition away from fossil fuels.

But major oil and gas producers and consumers blocked the initiative in Belém. As a compromise, Brazil’s COP presidency promised to draft proposals for two voluntary roadmaps: one to end deforestation and another to guide the transition away from fossil fuels.

Brazil has launched consultations seeking input for those plans, asking governments and stakeholders about technological and economic barriers, climate justice considerations and examples of best practice. Last week, COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago told Brazilian media that he would hold discussions on his roadmap proposal at the Santa Marta conference.

Colombia’s environment minister Irene Vélez Torres told reporters last week that “this is the moment to be honest about the challenges involved in transitioning away from fossil fuels”.

“It is not easy. It involves commitments from both the Global North and South. It involves interests and tensions at the subnational level,” she added. “Yet none of this diminishes its urgency or the need to reach agreements at the international multilateral level”.

Process to end fossil fuels

Vélez Torres said she hoped the Santa Marta meeting would help establish an ongoing process to advance discussions that often stall in the formal UN negotiations, where decisions are made by consensus and fossil fuel producers resist stronger language.

“This is the first conference, and we want it to be followed by another. We also want to establish a technical secretariat to sustain these debates,” said Vélez Torres, who added that the initiative would be “articulated with [the] COP30 and COP31” presidencies.

Colombia has been one of the few fossil fuel-producing countries that pledged to halt all new coal, oil and gas exploration. The move triggered backlash from industry and political opponents – with former president Iván Duque calling the decision “political and economic suicide”. The South American country depends on fossil fuels for about 10% of fiscal revenues and 4% of GDP, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Organisers of the Santa Marta conference said they expect between 40 and 80 high-level representatives from governments, both at national and subnational levels. Colombian president Gustavo Petro is expected to participate, and invitations have been extended to California governor Gavin Newsom and Dutch prime minister Rob Jetten.

Deep divisions persist as plastics treaty talks restart at informal meeting

No turning back

The conference comes amid renewed volatility in global energy markets. As the US and Israel’s war in Iran disrupts oil and gas supplies and threatens to cause severe global economic damage, analysts say governments should seek to reduce their dependency on fossil fuels through investments in renewables and energy efficiency.

The upcoming Santa Marta conference should build momentum to plan that transition away from fossil fuels and signal that “there is no turning back”, said Peter Newell, professor of international relations at the University of Sussex and one of the main proponents of a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty.

“Its outcomes, which might include a declaration on key principles and next steps (for the fossil fuel transition), should give renewed vigour to efforts within the UN climate negotiations to drive the agenda forward,” Newell said.

Because major fossil fuel producers have effectively “vetoed” discussions on a fossil fuel phase-out at COPs, he added, willing countries must move forward independently with initiatives like the Santa Marta conference.

Andreas Sieber, head of political strategy at the NGO 350.org, agreed that the push away from fossil fuels is “both necessary and economically inevitable”, adding that a conference on phasing out fossil fuels would have been “unthinkable just five years ago”.

Countries moving forward

COP30 host Brazil has taken the lead in developing its own national roadmap away from fossil fuels, which President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva requested his government to draft late last year. The roadmap is expected to be formally developed this year.

The plan – expected to include a dedicated energy transition fund – was initially due in February but has not yet been made public as ministers continue technical discussions.

In Europe, governments have also stepped up efforts to curb fossil fuel use following the energy shocks triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the conflict in the Middle East.

Leo Roberts, a fossil fuel transition analyst at the climate think tank E3G, said the recent surge in gas prices linked to the Iran conflict reinforces the case for accelerating the transition to boost energy security and protect people from price shocks.

“Hopefully, Santa Marta is able to really demonstrate that not only is there momentum at the international sphere through the COP30 roadmap process, but there’s huge momentum away from fossil fuels in the real world,” he said.

The post New summit in Colombia seeks to revive stalled UN talks on fossil fuel transition appeared first on Climate Home News.

New summit in Colombia seeks to revive stalled UN talks on fossil fuel transition

Climate Change

The US’s critical minerals club threatens an equitable clean energy transition

Nick Dearden is the director of Global Justice Now.

The US push for nations to join a club that would coordinate the trade of critical minerals outside China signals a giant shift in Washington’s vision for how to govern the global economy But it will, unfortunately, also hinder the clean energy transition.

Critical minerals such as lithium, nickel, copper and rare earths are needed to manufacture clean energy technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines and batteries on which the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy depends.

But these minerals also have applications for a wide range of advanced technologies, not least military equipment and digital infrastructure. In recent years, AI deployment and the build out of data centres have become the primary political justification for mineral extraction.

No US official mentioned clean energy technologies as they promoted the new minerals club in Washington last month. Instead, the trading bloc aims to break China’s dominance over mineral supply chains and ensure US access to the resources it needs for digital and military sectors.

Analysis by Global Justice Now found that almost one in five of the 33 minerals that the UK identified as critical in 2024 are not needed to achieve the International Energy Agency’s decarbonisation pathways. A further 15 play only a very small role and only seven require significant production increases for the clean energy transition.

Prioritise minerals for the energy transition

The urgency of addressing climate change means we must prioritise the use of minerals to rapidly and equitably wean the global economy off coal, oil and gas while reducing resource overconsumption in the Global North. The US approach could make this prioritisation a lot harder.

For Washington, this isn’t about addressing climate change, but America’s ever deepening rivalry with China, a renewable energy superpower. In contrast, Donald Trump has called climate change “a hoax” and overseen unprecedented climate deregulation in favour of fossil fuels.

The minerals trading bloc risks diverting mineral resources towards carbon-intensive military and technology build-up in the US, which is directly at odds with the need to use these resources to manufacture clean energy technologies.

What’s more, for the green transition to be just, fair and equitable, resource-rich governments must be able to refine and add value to their resources, creating jobs and economic development in the process. But Trump’s trading bloc is intended to tell “partner” countries what role they should play in the global mineral supply chains to best serve US interests.

Serving US interests rather than clean energy

Countries with the smallest and least developed economies stand to lose out.

More than a dozen countries have signed bilateral deals with the Trump administration. The terms of the deals appear to get better the richer a country is.

At the poorer end is the deal with DRC – an outright piece of imperialism with one-sided obligations that override the country’s mineral sovereignty by giving the US first dibs on a range of strategic mining sites and the energy needed to power these sites.

‘America needs you’: US seeks trade alliance to break China’s critical mineral dominance

In the middle, Malaysia committed to facilitate American involvement in its mineral sector and refrain from banning or imposing quotas on exports of raw minerals to the US. This risks restricting the development of Malaysia’s refining capacities, making value addition harder.

At the top end is the UK, which has signed a deal that includes a commitment to streamline mineral permitting, but appears more focused on facilitating financial services to members of the trading bloc.

Wherever countries sit in the pecking order, the agreements signed with the US limit governments’ strategic sovereignty over their resources and stifle their ability to create a more sustainable economy which meets people’s needs.

Tools for a way forward

There is some hope, however. Trump’s mineral trading bloc would operate with profoundly different rules than the neoliberal trade deals, which we have become used to.

Some of its components – like price floors and state ownership – have not been seen in trade deals for a long time. In the right hands, these tools could help governments plan, coordinate and prioritise a globally just green transition and break away from the ‘market knows best’ logic which has long locked poorer countries into low-value exports of raw materials.

If governments work together, outside the coercive US trade bloc, to adopt some of these tools and policies, they might be able to draw local benefits from their mineral wealth and build a genuinely fair and equitable trade in transition minerals.

The post The US’s critical minerals club threatens an equitable clean energy transition appeared first on Climate Home News.

The US’s critical minerals club threatens an equitable clean energy transition

Climate Change

Greenpeace urges governments to defend international law, as evidence suggests breaches by deep sea mining contractors

SYDNEY/FIJI, Monday 9 March 2026 — As the International Seabed Authority (ISA) opens its 31st Session today, Greenpeace International is calling on member states to take firm and swift action if breaches by subsidiaries and subcontractors of The Metals Company (TMC) are established. Evidence compiled and submitted to the ISA’s Secretary General suggests that violations of exploration contracts may have occurred.

Louisa Casson, Campaigner, Greenpeace International, said: “In July, governments at the ISA sent a clear message: rogue companies trying to sidestep international law will face consequences. Turning that promise into action at this meeting is far more important than rushing through a Mining Code designed to appease corporate interests rather than protect the common good. As delegations from around the world gather today, they must unite and confront the US and TMC’s neo-colonial resource grab and make clear that deep sea mining is a reckless gamble humanity cannot afford.”

The ISA launched an inquiry at its last Council meeting in July 2025, in response to TMC USA seeking unilateral deep sea mining licences from the Trump administration. If the US administration unilaterally allows mining of the international seabed, it would be considered in violation of international law.

Greenpeace International has compiled and submitted evidence to the ISA Secretary-General, Leticia Carvalho, to support the ongoing inquiry into deep sea mining contractors. This evidence shows that those supporting these unprecedented rogue efforts to start deep sea mining unilaterally via President Trump could be in breach of their obligations with the ISA.

The analysis focuses on TMC’s subsidiaries — Nauru Ocean Resources Inc (NORI) and Tonga Offshore Mining Ltd (TOML) — as well as Blue Minerals Jamaica (BMJ), a company linked to Dutch-Swiss offshore engineering firm Allseas, one of TMC’s subcontractors and largest shareholders. The information compiled indicates that their activities may violate core contractual obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). If these breaches are confirmed, NORI and TOML’s exploration contracts, which expire in July 2026 and January 2027 respectively, the ISA should take action, including considering not renewing the contract.

Letícia Carvalho has recently publicly advocated for governments to finalise a streamlined deep sea mining code this year and has expressed her own concerns with the calls from 40 governments for a moratorium. At a time when rogue actors are attempting to bypass or weaken the international system, establishing rules and regulations that will allow mining to start could mean falling into the trap of international bullies. A Mining Code would legitimise and drive investment into a flagging industry, supporting rogue actor companies like TMC and weakening deterrence against unilateral mining outside the ISA framework.

Casson added: “Rushing to finalise a Mining Code serves the interests of multinational corporations, not the principles of multilateralism. With what we know now, rules to mine the deep sea cannot coexist with ocean protection. Governments are legally obliged to only authorise deep sea mining if it can demonstrably benefit humanity – and that is non-negotiable. As the long list of scientific, environmental and social concerns with this industry keeps growing, what is needed is a clear political signal that the world will not be intimidated into rushing a mining code by unilateral threats and will instead keep moving towards a moratorium on deep sea mining.”

—ENDS—

Key findings from the full briefing:

- Following TMC USA’s application to mine the international seabed unilaterally, NORI and TOML have amended their agreements to provide payments to Nauru and Tonga, respectively, if US-authorised commercial mining goes ahead. This sets up their participation in a financial mechanism predicated on mining in contradiction to UNCLOS.

- NORI and TOML have signed intercompany intellectual property and data-sharing agreements with TMC USA, and the data obtained by NORI and TOML under the ISA exploration contracts has been key to facilitating TMC USA’s application under US national regulations.

- Just a few individuals hold key decision-making roles across the TMC and all relevant subsidiaries, making claims of independent management ungrounded. NORI, TOML, and TMC USA, while legally distinct, are managed as an integrated corporate group with a single, coordinated strategy under the direct control and strategic direction of TMC.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits