Global sea ice extent is at a record low for this time of year, due to rapid Antarctic sea ice melt and below-average Arctic coverage, new data reveals.

Antarctic sea ice extent has been tracking at record-low levels for almost the entire year, making headlines around the world.

It has now reached its annual maximum for the year, clocking in at 16.96m km2 on 10 September, according to provisional data from the National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC).

This is the smallest Antarctic sea ice maximum in the 45-year satellite record by “a wide margin”, the NSIDC says, and one of the earliest.

Antarctic conditions this year have been “truly exceptional” and “completely outside the bounds of normality”, one expert tells Carbon Brief.

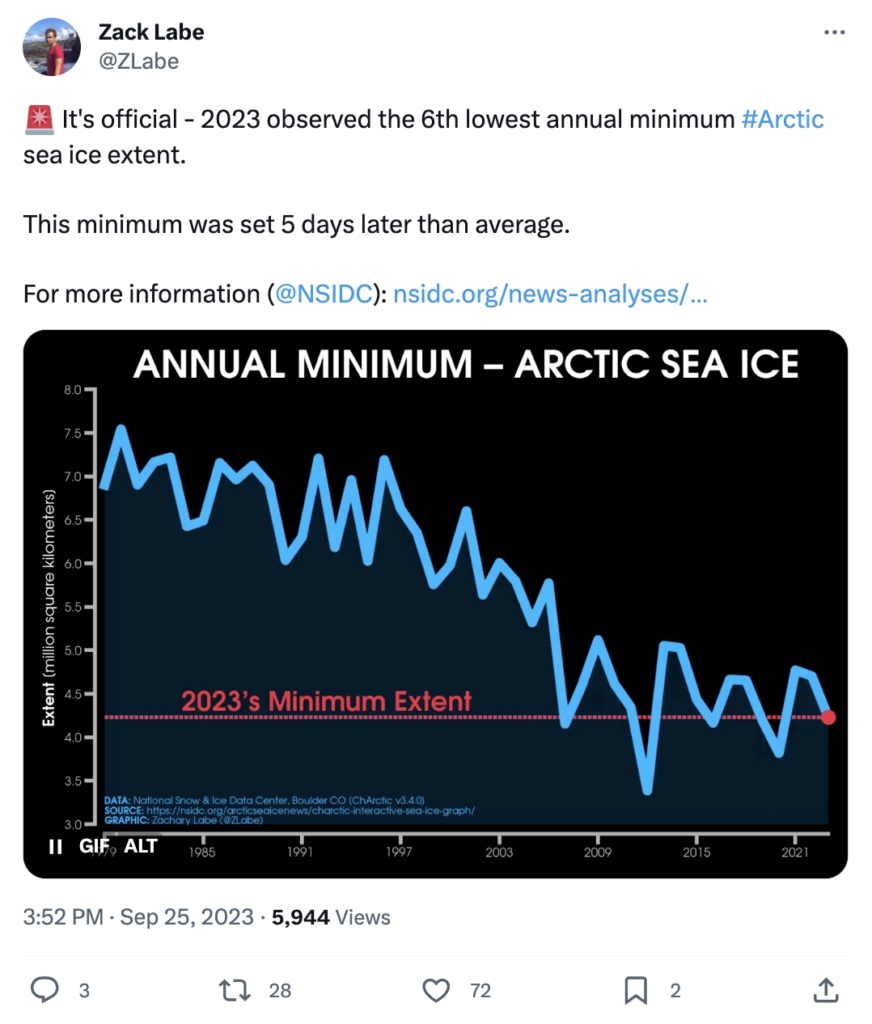

Meanwhile, Arctic sea ice extent reached its minimum for the year at 4.23m square kilometres (km2) on 19 September.

This is the sixth-lowest minimum on record and 1.99m km2 below the average maximum recorded over 1981-2010.

Record low global sea ice

Arctic sea ice has been melting for months, driven by long sunny days and warm temperatures. But, as winter approaches, the melt season has now come to an end. Arctic sea ice reached its minimum for the year on 19 September and is now growing towards its winter peak.

At the Earth’s other pole, the opposite is happening. Antarctic sea ice – which has been growing since February – reached its winter peak on 10 September. Its melt season has now begun.

Using satellite data, scientists track the seasonal growth and melt of sea ice, allowing them to determine the size of the annual minima and maxima. Recording the sea ice extent at each pole – the area of ocean with at least 15% sea ice coverage – is a key way to monitor the “health” of Antarctic sea ice.

The plots below show Arctic (left) and Antarctic (right) sea ice extent over June-October. Sea ice extent in 2023 is shown in blue, the 1981-2010 average in grey and other years in other colours.

In the Antarctic, sea ice extent has been tracking at record-low levels for months. Dr Ella Gilbert – a regional climate modeller at the British Antarctic Survey – tells Carbon Brief that Antarctic conditions this year have been “truly exceptional” and “completely outside the bounds of normality”.

Global sea ice extent – the sum of sea ice extent in the Arctic and Antarctic – has also been tracking at a record low for months.

The plot below shows the combined sea ice extent for the Arctic and Antarctic. The red line indicates sea ice extent in 2023, yellow shows 2016 and other blue lines indicate other years dating back until 1979 when the satellite record began.

‘Exceptional’ Antarctic melt

The Antarctic has attracted widespread media attention throughout this year. In February, Antarctic sea ice extent reached its summer minimum extent of 1.79m km2, setting the record for a second straight year.

Commenting on the new record low minimum – the third record to be set in seven years – one study warned that the Antarctic had entered a “new state”, in which the underlying processes controlling Antarctic sea ice coverage “may have altered”.

As the weather cooled in March, Antarctic sea ice “expanded at a fairly typical pace”, according to the NSIDC. Nonetheless, March 2023 average sea ice extent was the second lowest on record.

Antarctic sea ice extent remained “sharply below average throughout” April, clocking in with the second lowest daily extent on record by the end of the month.

Gilbert tells Carbon Brief that Antarctic sea ice “never really recovered” from its record-low February minimum, thanks to a “slow freeze-up”.

Antarctic sea ice grew only 2.87m km2 over May 2023 – considerably less than the average growth of 3.25m km2. Air temperatures were up to 4C above average over the Weddell sea during the month, but around 4C below average over the Amusden sea.

By 31 May, Antarctic sea ice extent was again at a record low extent, clocking in at around 700,000 km2 smaller than the previous daily record lows recorded in 1980, 2017 and 2019. Sea ice continued to track at “extreme record low levels” throughout June, according to the NSIDC.

The graphic below shows Antarctic daily sea ice extent in 2023 (red) compared to previous years over 1979-2023.

Dr Zachary Labe is a postdoctoral researcher working at NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and the Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences Program at Princeton University, and a Carbon Brief contributing editor.

He tells Carbon Brief that the record lows are linked to “both oceanic and atmospheric factors”, especially related to the strength of the Amundsen Sea Low – a low pressure trough named after the sea off West Antarctica that it typically sits above.

“Exceptionally low” sea ice extent continued into July, with the NSIDC noting that Antarctic ice extent as of mid-July was “more than 2.6 km2 below the 1981-2010 average, an area nearly as large as Argentina”. Antarctic sea ice extent was particularly low in the northern Weddell Sea, western Ross Sea and southern Bellingshausen Sea.

Antarctic sea ice continued to grow slowly as the season progressed. Average extent was at a record low in July, clocking in at 1.50m km2 below the previous record low set in 2022, the NSIDC noted. It added at the time:

“There is speculation that the Antarctic sea ice system has entered a new regime, in which ocean heat is now playing a stronger role in limiting autumn and winter ice growth and enhancing spring and summer melt.”

The graphic below shows Antarctic sea ice thickness in July 2023 (left) and the difference in sea ice thickness between July 2023 the 1981-2010 July average (right). In the right-hand map, the areas of deepest red show where sea ice thickness in July this year was below average.

By the beginning of August, Antarctic sea ice growth began to level off. On 15 August, Antarctic sea ice extent was 1.73m km2 below the previous record low for the date, which was set in 1986.

Antarctic sea ice growth then picked up as the month progressed. It continued to track at a record low, but increased more than average in the Bellingshausen and Amundsen Seas as well as in the Pacific Ocean.

On 10 September, Antarctic sea ice likely reached its annual maximum extent of 16.96m km2. This is the lowest sea ice maximum in the 45-year by “a wide margin”, the NSIDC says. The previous record-low Antarctic minimum extent was 17.99m km2.

It adds that this year’s winter peak is one of the earliest on record – 13 days earlier than the 1981-2010 average date of 23 September.

The plot below shows Antarctic sea ice extent on 10 September, with the median sea ice extent for 1981-2010 shown by the orange line.

Gilbert notes that scientists have “no evidence of comparably low winter extent in the satellite record, nor in reconstructions of the last century or so”, adding:

“Given how variable sea ice is, it’s hard to say for certain whether this is the beginning of a longer-term shift towards a new regime in Antarctic sea ice. However, climate models predict that Antarctic sea ice will decline, and I think it’s only a matter of time until we see the signature of climate warming in Antarctic sea ice trends.”

The record low Antarctic sea ice levels have received widespread attention in the media in recent months, with BBC News, the Times and the Daily Telegraph calling the record-low sea ice levels “mind–blowing” and “dramatic”.

The impact on wildlife has also caused alarm. At the end of August, multiple outlets reported on a new study that found thousands of emperor penguin chicks in Antarctica had died because of record-low sea ice levels in 2022.

And new research warns that the Antarctic is also warming twice as fast as the global average. (It is already well established that the Arctic has warmed four times faster than the global average over the past four decades.)

Arctic minimum

At the Earth’s other pole, the season has been less eventful.

The Arctic reached its winter peak on 6 March 2023 with a sea ice extent of 14.62m km2 – the fifth smallest winter peak in the 45-year satellite record. This point marked the beginning of the melt season for the year.

Arctic sea ice extent declined in the week following the March peak, but cool weather nearly halted the ice melt during the second half of the month. Slow Arctic ice melt continued throughout April with “only” 20,600 km2 of ice lost per day on average, according to the NSIDC.

Slower-than-average sea ice melt persisted throughout much of May. Air temperatures over the Arctic ocean were around 1-4C below average throughout the month – except for over the Barents, Kara, and Beaufort Seas, where temperatures were 2-6C above average.

The map below shows the regional seas that make up the Arctic Ocean.

Sea ice melt sped up as the season progressed, resulting in faster-than-average melting throughout June. By the end of that month, average Arctic sea ice extent was 10.96m km2 – the 13th lowest for the time of year in the satellite record.

Arctic sea ice extent declined at a near-average pace throughout July, clocking in at the 12th lowest in the satellite record for the time of year.

However, record-breaking heat swept across the world in August, causing Arctic sea ice melt to accelerate, the NSIDC noted at the time.

Temperatures in the first half of August were “below average north of Greenland, above average in the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas, and considerably above average in the Kara and Barents Seas,” the NSIDC said.

The maps below shows absolute air temperatures in the Arctic in August 2023 (left) and the difference in air temperature between August 2023 the 1981-2010 August average (right). In the right-hand map, the areas of deepest red show where August this year was substantially hotter than average.

By the middle of August, sea ice extent was near average on the Atlantic side of the Arctic, but “well below average” in most other regions other than a tongue of ice extending toward the coast in the East Siberian Sea, the NSIDC said:

“The Northwest Passage appears to be on the verge of becoming nearly ice free, particularly the southern route, known as Amundsen’s route.”

As is typical of August, the pace of sea ice loss slowed during the second half of the month as cooler conditions set in.

The left-hand map below shows Arctic sea ice concentration – a measure of the amount of sea ice in a given area, usually described as a percentage – during August 2023. The areas shaded white indicate a high concentration.

The right-hand map shows the difference between this August and the 1981-2010 average, where red indicates a lower sea ice concentration in 2023 than the baseline.

Labe tells Carbon Brief that there have been some “particularly large regional extremes” around the Arctic this season.

For example, he highlights the “massive amount of open water on the Pacific side of the Arctic, which stretches from the Beaufort Sea to the East Siberian Sea”. Sea ice extent in this region dropped to the second lowest in the satellite-era, beaten only in the year 2012, he says.

Labe adds that within the main Arctic ice pack, there are “many areas of open water” this year, indicating that the ice is not very compacted. By mid September, sea-ice area – a measure of how compacted the ice is – reached its fourth lowest for the time of year, he says.

He also notes that sea ice was “significantly thinner than average in the Beaufort sea region” in August.

Arctic sea ice extent reached its minimum for the year at 4.23m square kilometres (km2), on 19 September, according to the NSIDC. This is the sixth lowest in a satellite record – 1.99m km2 smaller than the average minimum over 1981-2010 .

Days before the minimum was announced, the Marine Climate Change Impacts Partnership published a review paper on Arctic sea ice. It found that the September minimum Arctic sea ice extent has reduced by around 12% per decade compared to the 1981-2010 average.

It added:

“More than half the observed loss of Arctic sea ice can be directly attributed to warming caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.”

Labe tells Carbon Brief that the Arctic today is “radically different” than it was only two or three decades ago. “This is due to human-caused climate change,” he says.

According to the NSIDC, the 17 lowest Arctic sea ice minima on record have occurred in the past 17 years.

The post ‘Exceptional’ Antarctic melt drives months of record-low global sea ice cover appeared first on Carbon Brief.

‘Exceptional’ Antarctic melt drives months of record-low global sea ice cover

Climate Change

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

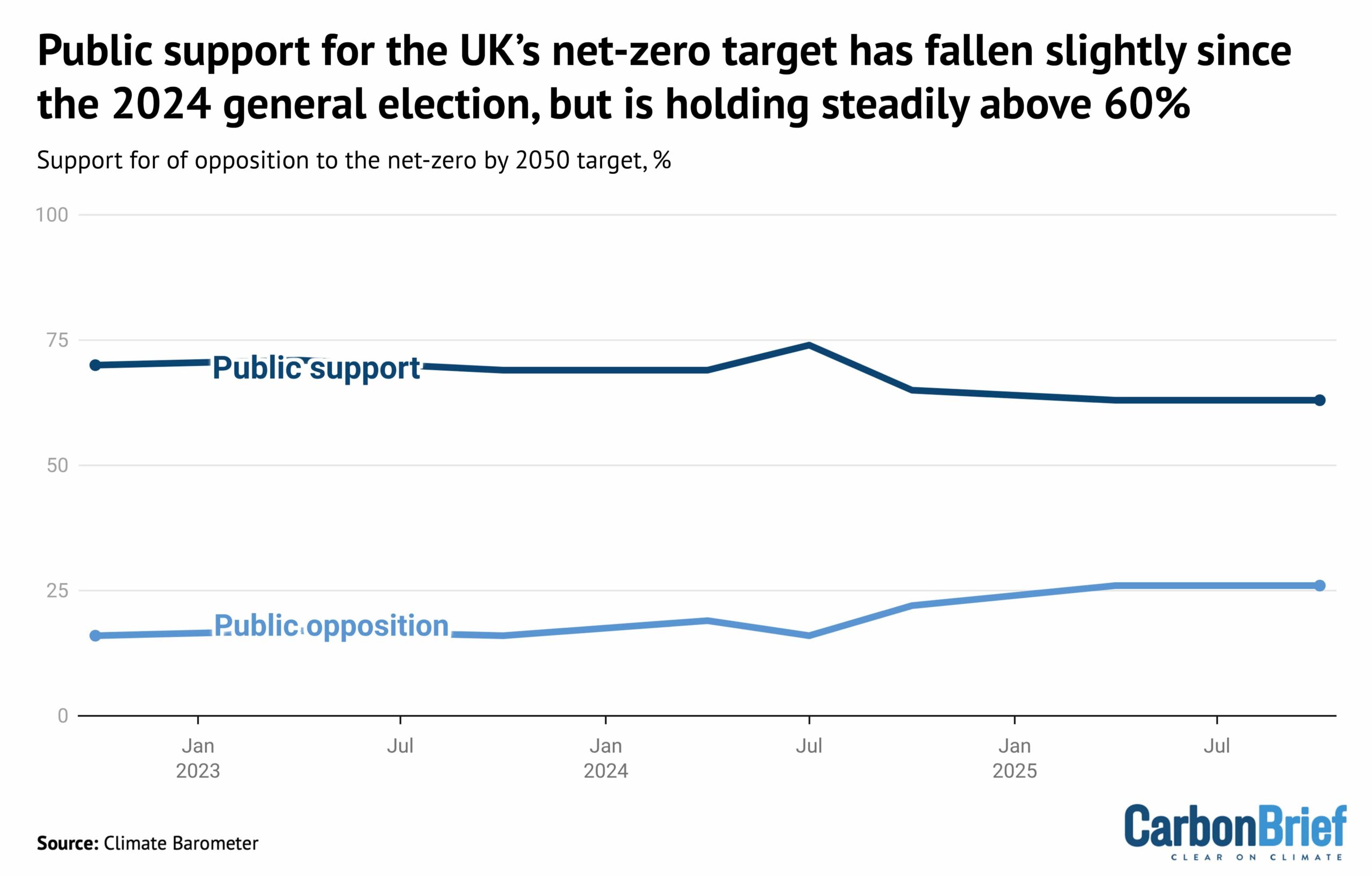

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

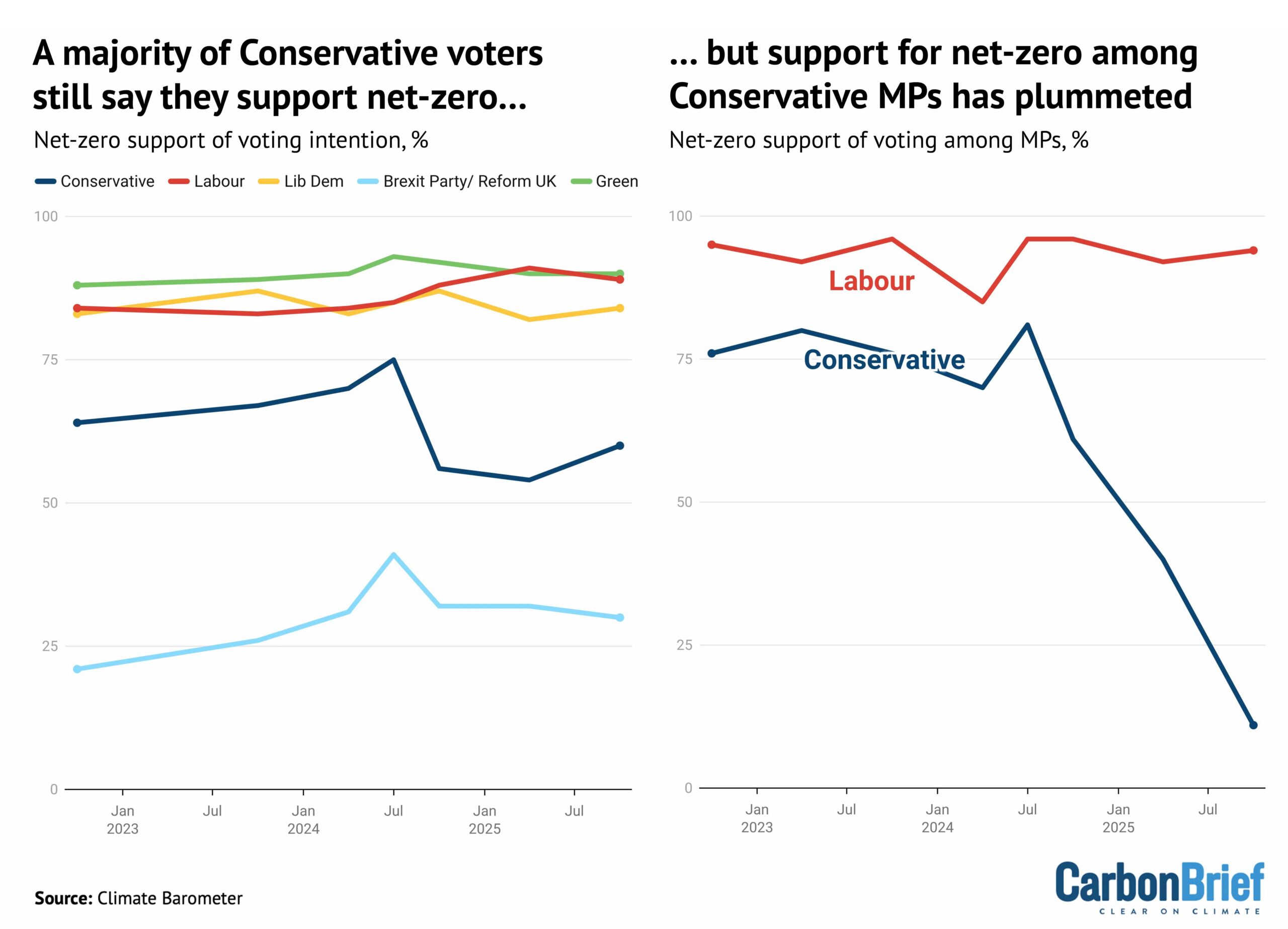

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

Seven Pacific island nations say they will demand heftier levies on global shipping emissions if opponents of a green deal for the industry succeed in reopening negotiations on the stalled accord.

The United States and Saudi Arabia persuaded countries not to grant final approval to the International Maritime Organization’s Net-Zero Framework (NZF) in October and they are now leading a drive for changes to the deal.

In a joint submission seen by Climate Home News, the seven climate-vulnerable Pacific countries said the framework was already a “fragile compromise”, and vowed to push for a universal levy on all ship emissions, as well as higher fees . The deal currently stipulates that fees will be charged when a vessel’s emissions exceed a certain level.

“For many countries, the NZF represents the absolute limit of what they can accept,” said the unpublished submission by Fiji, Kiribati, Vanuatu, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands.

The countries said a universal levy and higher charges on shipping would raise more funds to enable a “just and equitable transition leaving no country behind”. They added, however, that “despite its many shortcomings”, the framework should be adopted later this year.

US allies want exemption for ‘transition fuels’

The previous attempt to adopt the framework failed after governments narrowly voted to postpone it by a year. Ahead of the vote, the US threatened governments and their officials with sanctions, tariffs and visa restrictions – and President Donald Trump called the framework a “Green New Scam Tax on Shipping”.

Since then, Liberia – an African nation with a major low-tax shipping registry headquartered in the US state of Virginia – has proposed a new measure under which, rather than staying fixed under the NZF, ships’ emissions intensity targets change depending on “demonstrated uptake” of both “low-carbon and zero-carbon fuels”.

The proposal places stringent conditions on what fuels are taken into consideration when setting these targets, stressing that the low- and zero-carbon fuels should be “scalable”, not cost more than 15% more than standard marine fuels and should be available at “sufficient ports worldwide”.

This proposal would not “penalise transitional fuels” like natural gas and biofuels, they said. In the last decade, the US has built a host of large liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals, which the Trump administration is lobbying other countries to purchase from.

The draft motion, seen by Climate Home News, was co-sponsored by US ally Argentina and also by Panama, a shipping hub whose canal the US has threatened to annex. Both countries voted with the US to postpone the last vote on adopting the framework.

The IMO’s Panamanian head Arsenio Dominguez told reporters in January that changes to the framework were now possible.

“It is clear from what happened last year that we need to look into the concerns that have been expressed [and] … make sure that they are somehow addressed within the framework,” he said.

Patchwork of levies

While the European Union pushed firmly for the framework’s adoption, two of its shipping-reliant member states – Greece and Cyprus – abstained in October’s vote.

After a meeting between the Greek shipping minister and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister in January, Greece said a “common position” united Greece, Saudi Arabia and the US on the framework.

If the NZF or a similar instrument is not adopted, the IMO has warned that there will be a patchwork of differing regional levies on pollution – like the EU’s emissions trading system for ships visiting its ports – which will be complicated and expensive to comply with.

This would mean that only countries with their own levies and with lots of ships visiting their ports would raise funds, making it harder for other nations to fund green investments in their ports, seafarers and shipping companies. In contrast, under the NZF, revenues would be disbursed by the IMO to all nations based on set criteria.

Anais Rios, shipping policy officer from green campaign group Seas At Risk, told Climate Home News the proposal by the Pacific nations for a levy on all shipping emissions – not just those above a certain threshold – was “the most credible way to meet the IMO’s climate goals”.

“With geopolitics reframing climate policy, asking the IMO to reopen the discussion on the universal levy is the only way to decarbonise shipping whilst bringing revenue to manage impacts fairly,” Rios said.

“It is […] far stronger than the Net-Zero Framework that is currently on offer.”

The post Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen appeared first on Climate Home News.

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

Climate Change

Doubts over European SAF rules threaten cleaner aviation hopes, investors warn

Doubts over whether governments will maintain ambitious targets on boosting the use of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) are a threat to the industry’s growth and play into the hands of fossil fuel companies, investors warned this week.

Several executives from airlines and oil firms have forecast recently that SAF requirements in the European Union, United Kingdom and elsewhere will be eased or scrapped altogether, potentially upending the aviation industry’s main policy to shrink air travel’s growing carbon footprint.

Such speculation poses a “fundamental threat” to the SAF industry, which mainly produces an alternative to traditional kerosene jet fuel using organic feedstocks such as used cooking oil (UCO), Thomas Engelmann, head of energy transition at German investment manager KGAL, told the Sustainable Aviation Fuel Investor conference in London.

He said fossil fuel firms would be the only winners from questions about compulsory SAF blending requirements.

The EU and the UK introduced the world’s first SAF mandates in January 2025, requiring fuel suppliers to blend at least 2% SAF with fossil fuel kerosene. The blending requirement will gradually increase to reach 32% in the EU and 22% in the UK by 2040.

Another case of diluted green rules?

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, CEO of French oil and gas company TotalEnergies Patrick Pouyanné said he would bet “that what happened to the car regulation will happen to the SAF regulation in Europe”.

The EU watered down green rules for car-makers in March 2025 after lobbying from car companies, Germany and Italy.

“You will see. Today all the airline companies are fighting [against the EU’s 2030 SAF target of 6%],” Pouyanne said, even though it’s “easy to reach to be honest”.

While most European airline lobbies publicly support the mandates, Ryanair Group CEO Michael O’Leary said last year that the SAF is “nonsense” and is “gradually dying a death, which is what it deserves to do”.

EU and UK stand by SAF targets

But the EU and the British government have disputed that. EU transport commissioner Apostolos Tzitzikostas said in November that the EU’s targets are “stable”, warning that “investment decisions and construction must start by 2027, or we will miss the 2030 targets”.

UK aviation minister Keir Mather told this week’s investor event that meeting the country’s SAF blending requirement of 10% by 2030 was “ambitious but, with the right investment, the right innovation and the right outlook, it is absolutely within our reach”.

“We need to go further and we need to go faster,” Mather said.

SAF investors and developers said such certainty on SAF mandates from policymakers was key to drawing the necessary investment to ramp up production of the greener fuel, which needs to scale up in order to bring down high production costs. Currently, SAF is between two and seven times more expensive than traditional jet fuel.

Urbano Perez, global clean molecules lead at Spanish bank Santander, said banks will not invest if there is a perceived regulatory risk.

David Scott, chair of Australian SAF producer Jet Zero Australia, said developing SAF was already challenging due to the risks of “pretty new” technology requiring high capital expenditure.

“That’s a scary model with a volatile political environment, so mandate questioning creates this problem on steroids”, Scott said.

Others played down the risk. Glenn Morgan, partner at investment and advisory firm SkiesFifty, said “policy is always a risk”, adding that traditional oil-based jet fuel could also lose subsidies.

Asian countries join SAF mandate adopters

In Asia, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand and Japan have recently adopted SAF mandates, and Matti Lievonen, CEO of Asia-based SAF producer EcoCeres, predicted that China, Indonesia and Hong Kong would follow suit.

David Fisken, investment director at the Australian Trade and Investment Commission, said the Australian government, which does not have a mandate, was watching to see how the EU and UK’s requirements played out.

The US does not have a SAF mandate and under President Donald Trump the government has slashed tax credits available for SAF producers from $1.75 a gallon to $1.

Is the world’s big idea for greener air travel a flight of fancy?

SAF and energy security

SAF’s potential role in boosting energy security was a major theme of this week’s discussions as geopolitical tensions push the issue to the fore.

Marcella Franchi, chief commercial officer for SAF at France’s Haffner Energy, said the Canadian government, which has “very unsettling neighbours at the moment”, was looking to produce SAF to protect its energy security, especially as it has ample supplies of biomass to use as potential feedstock.

Similarly, German weapons manufacturer Rheinmetall said last year it was working on plans that would enable European armed forces to produce their own synthetic, carbon-neutral fuel “locally and independently of global fossil fuel supply chain”.

Scott said Australia needs SAF to improve its fuel security, as it imports almost 99% of its liquid fuels.

He added that support for Australian SAF production is bipartisan, in part because it appeals to those more concerned about energy security than tackling climate change.

The post Doubts over European SAF rules threaten cleaner aviation hopes, investors warn appeared first on Climate Home News.

Doubts over European SAF rules threaten cleaner aviation hopes, investors warn

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits