Billed as the “Amazon COP”, the UN climate talks will see the debut of Brazil’s flagship fund to “reward” tropical countries for keeping their forests intact.

The Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) will be launched at the COP30 leaders’ summit on 6 November.

The fund aims to raise and invest $125bn from a range of sources, with excess returns channelled to up to 74 developing countries that sufficiently protect their forests.

This, according to Brazil, would make it one of the biggest multilateral investment funds for nature.

(For comparison, the Green Climate Fund’s portfolio is around $18bn.)

While Brazil expects TFFF to “transform the world’s approach to environmental conservation”, many critics remain unconvinced.

They argue that conservation funding for climate-critical forests should not depend on “betting on stock market prices” and instead call for new biodiversity finance.

Here, Carbon Brief takes a closer look at where the fund came from, how it will be set up and how it is supposed to work.

What is the Tropical Forest Forever Facility?

First officially proposed by Brazil at COP28 in Dubai in 2023, the Tropical Forest Forever Facility aims to pay up to 74 developing tropical forest countries for keeping their existing old-growth forests intact.

It plans to do this by raising $25bn in capital from wealthy “sponsor” governments and philanthropies, which – it hopes – will attract an additional $100bn in private investment.

Returns on these investments will go towards paying back investors and making “forest payments” to countries that increase or maintain their forest cover.

On 4 November, Brazil’s finance minister Fernando Haddad told Bloomberg that “he believed the fund could raise $10bn by next year”, less than half the original target.

While the facility’s official launch is slated for COP30, its rules are still being finalised after several iterations of “concept notes” and consultations.

However, the idea that underpins the fund is not new.

Former World Bank treasurer Kenneth Lay first floated the idea of a Tropical Forest Finance Facility around 15 years ago.

Lay and others later envisioned the TFFF as a “pay-for-performance” sovereign wealth fund for forests. In their design of the TFFF, loans from developed countries and private investors would have been invested in the debt markets of tropical forest countries, with excess returns being allocated annually as “rainforest rewards”.

In their thinking, TFFF offered a “highly-visible, large-scale reward for successfully tackling deforestation without increasing funding demands” on developed countries, according to a 2018 article for the Center for Global Development.

Others central to the TFFF’s current design are Christopher Egerton-Warburton – founder of London-based Lion’s Head Global Partners, who is credited with engineering the facility’s financial structure – and Garo Batmanian, director of Brazil’s forestry service.

What is it designed to achieve?

The ultimate goal of the TFFF is to pay for the conservation of the world’s major rainforests, which provide a range of ecosystem services, including carbon storage.

In a statement from the COP30 presidency, André Aquino, special advisor on economy and environment at Brazil’s ministry of environment, said:

“What the TFFF seeks is for the world to remunerate part of these services. It is to remunerate forests as the basis of life, as the basis of the economy, for our well-being.”

On the ground, this mechanism could help landowners to conserve trees and forests by ensuring that the value they bring as standing forests is higher than from cutting them down.

The facility also intends to finance long-term objectives for forest conservation, including policies and programmes for sustainable use and restoration.

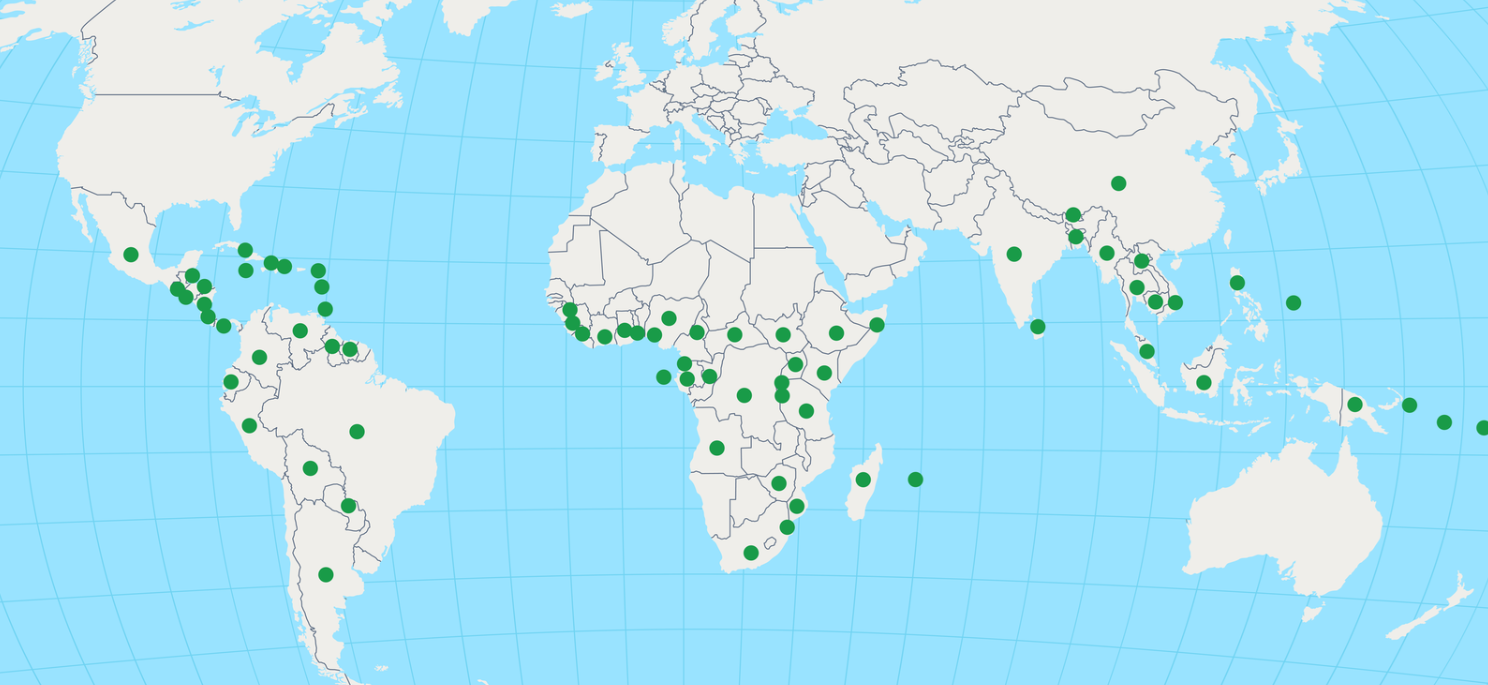

More than 70 developing countries that are home to more than 1bn hectares of tropical and sub-tropical forests could be potential recipients from this facility. These countries span the Amazon, Congo and Mekong basins, as well as many other regions.

The following map shows the countries that host tropical rainforests and are potentially eligible to receive funds from the TFFF.

To be selected as beneficiaries, countries will require transparent financial management systems and must commit to allocating 20% of the funds to Indigenous peoples and traditional communities, according to the draft rules.

These countries would need to have a deforestation rate – averaged over the previous three years – of no more than 0.5% of their total forested area, with standing forest areas having a canopy cover of at least 20-30% in each hectare to be eligible for payments.

The TFFF’s third concept note says that areas that transition from above to below this 20-30% threshold would be “considered deforested”.

In a recent Yale Environment 360 article, forest ecologists warned that the low level of this threshold – for what counts as a forested area – is “not scientifically credible” and “would allow payments even where industrial logging is occurring in primary forests”.

However, TFFF argues that “including forest areas with lower canopy cover does provide an incentive for maintaining these areas”.

Additionally, payments would be reduced for each hectare of forest loss and for each hectare degraded by fire.

The funds for Indigenous peoples would be “put aside in a different account, following different rules”, Aquino said during a press briefing attended by Carbon Brief.

Brazil’s ministry of environment and climate change invited five countries with rainforests to support the creation of the fund: Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Indonesia and Malaysia.

Individual national governments that are beneficiaries of the scheme would be free to define how and where the generated funds would be distributed.

How will the fund work?

The TFFF is split into two entities, with a secretariat to coordinate between them.

The facility is the first of these. It is tasked with setting up the rewards system, eligibility criteria, monitoring methodologies and disbursement rules, as well as engaging with participating recipient countries.

The other is the TFFF’s main financial arm, the Tropical Forest Investment Fund (TFIF) – responsible for raising and managing the TFFF’s resources.

So far, five potential sponsor countries have shown interest in supporting the fund: France, Germany, Norway, the United Arab Emirates and the UK.

These countries, along with five potential recipient countries – Brazil, Colombia, the DRC, Ghana, Indonesia and Malaysia – formed an interim steering committee to shape TFFF’s development.

According to its third concept note, published in October, the TFIF would be a “blended finance vehicle”, pooling public, philanthropic and private funding.

The TFIF is split into two tranches. The first is a “sponsor” tranche, where donor countries and philanthropies are invited to contribute long-term, low-cost capital investment to the tune of $25bn, either from long-term loans, guarantees or outright grants.

So far, Brazil’s initial pledge of $1bn to the facility is the only such pledge. Other governments, such as the UK, have played an “active part” in establishing the TFFF.

(Five days before COP30 kicked off, Bloomberg reported that the UK would not be investing in the TFFF, after the government’s treasury department warned that the investment is “not something the UK can afford at a time when it’s trying to tackle its surging debt burden”.)

This $25bn from sponsor countries, in turn, would be expected to absorb risk, cover losses and serve as a catalyst to raise $100bn from institutional investors in the global bond market.

(This sum raised from private investors is described as the “senior market debt” tranche of investment: if the markets see a downturn, private investors are protected first, making their interests “senior” to donor and recipient countries.)

TFIF and its asset managers then invest this $125bn of capital into a mixed portfolio of investments, including public and corporate market bonds, but excluding those with a significant environmental impact. (In a joint letter, issued in October, advocacy and research groups called for a more detailed exclusion criteria.)

Income from these investments, in turn, will be used to pay investors first, then interest to donor countries and, finally, to pay participating forest countries. The payments to participating countries will be roughly $4 per hectare of standing forest (subject to annual adjustment for inflation), as verified by satellite imagery.

The World Bank confirmed in September 2025 that it will serve as a trustee to the facility and host its interim secretariat.

Liane Schalatek, a climate finance expert and associate director of German policy thinktank Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung’s Washington office, tells Carbon Brief:

“It’s a very clear hierarchy: you serve the money raised on the market and capital investors first before you go to the intended purpose of the fund – and that is compensating countries for basically leaving their tropical forest standing. To me, it seems that the focus is on the money, not necessarily on the outcome. That is really worrisome.”

While sponsor countries are guaranteed their money back over a 40-year period, payouts to forest countries depend on investment returns. These are subject to market risks and volatility and, therefore, are not guaranteed.

According to Frederic Hache, co-founder of the EU Green Finance Observatory thinktank, payouts promised by the TFFF are “really not appropriate to the emergency of the [biodiversity and climate] crises” and do not address their “root drivers”. Hache tells Carbon Brief:

“Even if you meet the very hard criteria as a country to get this money, obtaining this conservation funding is conditional upon financial market conditions and the skill of an asset manager. That’s not very generous and that’s not very appropriate.”

Hache warns that if the fund does not make enough money or experiences losses, the “first thing that is impacted is the forest payment”, which could be put on hold, while “sponsor capital protects private investors with taxpayer money”.

What issues might the fund face?

Civil-society organisations and climate finance experts have warned of several risks and gaps within the facility.

Finance fragmentation

Experts who spoke to Carbon Brief expressed concerns that TFFF could erode the legitimacy of existing, but under-resourced, multilateral funds for climate and biodiversity, as well as dilute the legal obligations of developed countries to pay their “fair share” of nature finance.

While the TFFF hopes to contribute to the goals of all three UN conventions – climate, biodiversity and land degradation – the fund is not officially part of any of the three treaties.

To Schalatek, the fact that the “biggest thing that is going to come out of COP30” is “outside” the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and depends to a large extent on private investment is cause for disappointment.

A keenly awaited report ahead of COP30 is a roadmap towards a wider climate finance target of $1.3tn a year, which could include various sources beyond the jurisdiction of the UN climate process.

Schalatek tells Carbon Brief:

“While we’re trying to have a discussion about protecting the provision of public finance from developed to developing countries [after Baku and amid aid cuts], TFFF is almost contributing to a further undermining of the financial mechanism of the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement.”

Sarah Colenbrander, director of the climate and sustainability programme at the UK-based global development thinktank ODI, tells Carbon Brief:

“The creation of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility risks not increasing total resources for climate and biodiversity finance, but rather fragmenting the funds already available.”

Potential financial risk

Given the fund’s long-term horizon, a significant challenge is managing financial risk down the line.

This could take the form of a debt crisis in emerging markets, which could “wipe out” sponsor capital and “halt rainforest flows, possibly before they even begin”, economists Max Alexander Matthey and Prof Aidan Hollis wrote in a Substack post in September.

Higher return rates for investors – as mentioned in the third draft of TFFF’s concept note – in combination with high financial fees and operational costs, have left several experts questioning what remains in the way of “rewards” to rainforest countries.

Hache tells Carbon Brief that the TFFF might be “fantastic” for investors who get a “AAA-rated investment without sacrificing any returns”, but real risk is borne by tropical forest countries.

In addition, the mooted payments of $4 a hectare is “ridiculous and not enough to displace alternatives” such as growing cash crops for export, he says, adding:

“$125bn sounds much better than, ‘Oh, we put $2.5bn on the table conditionally’. While there is very little political appetite for giving grant money, this is one of these mechanisms where innovation can obfuscate the lack of ambition and generosity by global-north countries.”

Commodification and transparency

Other experts fear that the new facility could contribute to the commodification of forests and a possible lack of adequate accountability.

The Global Forest Coalition (GFC), an alliance of not-for-profit organisations and Indigenous groups working on forest issues worldwide, have urged countries, Indigenous peoples and civil society to reject the TFFF.

In a press release in October, the GFC said that the TFFF views forests as “financial assets” and warned that the fund is “subject to investment returns, liquidation risks and payouts that are not even guaranteed”.

The press release quotes Mary Louise Malig, policy director at the GFC, who said:

“This is not about conserving forests; it is about conserving the power of elites over forests. It is the continuation of a free market model dressed up as climate finance.”

Information on transparency and governance of the TFFF is unavailable at the moment, says Tyala Ifwanga, forest governance campaigner at Fern, a civil-society organisation that works to protect forest people’s rights in the EU. She tells Carbon Brief that this makes it difficult to assess whether the facility can ensure payments meet the fund’s objectives, adding:

“Corruption is not the only issue we should have in mind here. Some tropical forest countries have autocratic regimes and very limited civic space.”

Pablo Solón, executive director of the Solón Foundation, is also quoted in the GFC press release. He warned:

“The TFFF is a distraction that diverts attention and resources from real solutions like regulation, corporate accountability and direct financing for Indigenous and local initiatives.”

Low Indigenous involvement

Another concern highlighted by the GFC is that while Indigenous peoples and local communities are expected to have “consultative roles”, the “decision-making power rests with governments and financial institutions”.

According to Fern’s Ifwanga, the Global Alliance for Territorial Community – a political platform bringing together coalitions of Indigenous peoples and local communities for defending nature – was involved in developing the TFFF concept notes related to Indigenous peoples and local communities.

She says that although the alliance agrees with the facility, “they are very aware that a lot of work remains to be done to ensure that their voices are heard at every level of the mechanism”.

She also encourages countries to increase direct access to funds for Indigenous communities.

Schalatek says that it is “sinister” that forest communities are being asked to “provide continued stewardship” and preserve forests “without any predictability on how much they’re going to receive for it”, while fund managers can get their money back. She concludes:

“This [TFFF] is exactly the kind of vehicle that gives developed countries the sick leave to not contribute to the GCF [Green Climate Fund], not contribute to the Adaptation Fund…We all know the world has changed, but that doesn’t apply to legal obligations you have signed on to.

“One could probably argue that the Brazilians put a lot more effort into the TFFF than in, for example, thinking about how to deal with the finance agenda within COP30.”

The post COP30: Could Brazil’s ‘Tropical Forest Forever’ fund help tackle climate change? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

COP30: Could Brazil’s ‘Tropical Forest Forever’ fund help tackle climate change?

Climate Change

Greenpeace urges governments to defend international law, as evidence suggests breaches by deep sea mining contractors

SYDNEY/FIJI, Monday 9 March 2026 — As the International Seabed Authority (ISA) opens its 31st Session today, Greenpeace International is calling on member states to take firm and swift action if breaches by subsidiaries and subcontractors of The Metals Company (TMC) are established. Evidence compiled and submitted to the ISA’s Secretary General suggests that violations of exploration contracts may have occurred.

Louisa Casson, Campaigner, Greenpeace International, said: “In July, governments at the ISA sent a clear message: rogue companies trying to sidestep international law will face consequences. Turning that promise into action at this meeting is far more important than rushing through a Mining Code designed to appease corporate interests rather than protect the common good. As delegations from around the world gather today, they must unite and confront the US and TMC’s neo-colonial resource grab and make clear that deep sea mining is a reckless gamble humanity cannot afford.”

The ISA launched an inquiry at its last Council meeting in July 2025, in response to TMC USA seeking unilateral deep sea mining licences from the Trump administration. If the US administration unilaterally allows mining of the international seabed, it would be considered in violation of international law.

Greenpeace International has compiled and submitted evidence to the ISA Secretary-General, Leticia Carvalho, to support the ongoing inquiry into deep sea mining contractors. This evidence shows that those supporting these unprecedented rogue efforts to start deep sea mining unilaterally via President Trump could be in breach of their obligations with the ISA.

The analysis focuses on TMC’s subsidiaries — Nauru Ocean Resources Inc (NORI) and Tonga Offshore Mining Ltd (TOML) — as well as Blue Minerals Jamaica (BMJ), a company linked to Dutch-Swiss offshore engineering firm Allseas, one of TMC’s subcontractors and largest shareholders. The information compiled indicates that their activities may violate core contractual obligations under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). If these breaches are confirmed, NORI and TOML’s exploration contracts, which expire in July 2026 and January 2027 respectively, the ISA should take action, including considering not renewing the contract.

Letícia Carvalho has recently publicly advocated for governments to finalise a streamlined deep sea mining code this year and has expressed her own concerns with the calls from 40 governments for a moratorium. At a time when rogue actors are attempting to bypass or weaken the international system, establishing rules and regulations that will allow mining to start could mean falling into the trap of international bullies. A Mining Code would legitimise and drive investment into a flagging industry, supporting rogue actor companies like TMC and weakening deterrence against unilateral mining outside the ISA framework.

Casson added: “Rushing to finalise a Mining Code serves the interests of multinational corporations, not the principles of multilateralism. With what we know now, rules to mine the deep sea cannot coexist with ocean protection. Governments are legally obliged to only authorise deep sea mining if it can demonstrably benefit humanity – and that is non-negotiable. As the long list of scientific, environmental and social concerns with this industry keeps growing, what is needed is a clear political signal that the world will not be intimidated into rushing a mining code by unilateral threats and will instead keep moving towards a moratorium on deep sea mining.”

—ENDS—

Key findings from the full briefing:

- Following TMC USA’s application to mine the international seabed unilaterally, NORI and TOML have amended their agreements to provide payments to Nauru and Tonga, respectively, if US-authorised commercial mining goes ahead. This sets up their participation in a financial mechanism predicated on mining in contradiction to UNCLOS.

- NORI and TOML have signed intercompany intellectual property and data-sharing agreements with TMC USA, and the data obtained by NORI and TOML under the ISA exploration contracts has been key to facilitating TMC USA’s application under US national regulations.

- Just a few individuals hold key decision-making roles across the TMC and all relevant subsidiaries, making claims of independent management ungrounded. NORI, TOML, and TMC USA, while legally distinct, are managed as an integrated corporate group with a single, coordinated strategy under the direct control and strategic direction of TMC.

Climate Change

After a Decade of Missteps, a Texas City Careens Toward a Water-Shortage Catastrophe

Officials in Corpus Christi expect a “water emergency” within months and fully run out of water next year. That would halt jet fuel supplies to Texas airports, fuel a surge in gasoline prices and trigger an “economic disaster” without precedent, former officials said.

CORPUS CHRISTI, Texas—The imminent depletion of water supplies in Corpus Christi threatens to cut off the flow of jet fuel to Texas airports and other oil exports from one of the nation’s largest petroleum ports, triggering potential shockwaves through energy markets in Texas and beyond.

After a Decade of Missteps, a Texas City Careens Toward a Water-Shortage Catastrophe

Climate Change

Is the FBI Investigating Environmental Activists?

A recent visit by an FBI agent to a climate activist hints at a broadening Trump administration effort to target political opponents.

NEW YORK CITY—The group in the Brooklyn studio seemed harmless. There was a graduate student, a Yiddish teacher, a hairdresser. Fifteen people had gathered on a Wednesday night for a training offered by Extinction Rebellion NYC and Climate Defiance, two climate activist groups that engage in nonviolent civil disobedience and theatrical protest.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits