China and Chinese interests own about 1% of all foreign-owned farmland.

China and Chinese interests own about 1% of all foreign-owned farmland.

Of all foreign-owned U.S. land, Canadian investors owned the most at 12.8 million acres. This makes up 31% of all foreign-owned U.S. land. Four other countries held 12.4 million acres combined, or another 31% of foreign-owned land: the Netherlands (12%), Italy (7%), the United Kingdom (6%), and Germany (6%). China holds less than 1%.

1% of 3.1% is .031% or 0.00031. It’s infinitesimal, but more that enough to rile up the morons.

Renewable Energy

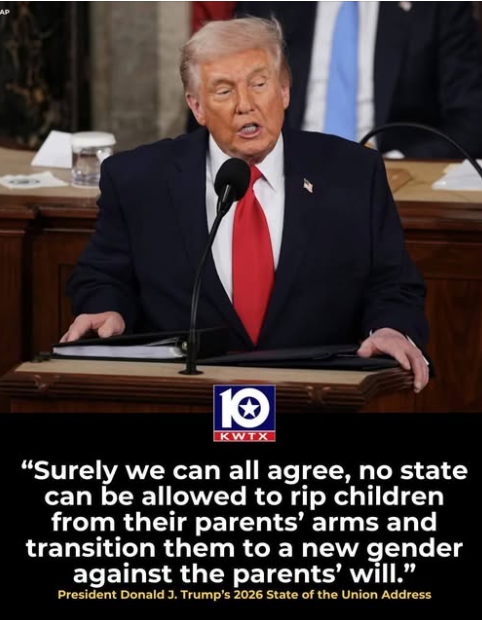

Forced Transgendering of America’s Little Kids

How often does this happen? How about never?

How often does this happen? How about never?

Trump loves to say that little boys go to school and come back home little girls.

He’s the most powerful person in the world for exactly one reason: We’re a nation of morons.

Renewable Energy

Illegal Aliens and U.S. Veterans

Two comments:

Two comments:

That the United States has homeless veterans is a national (and international) disgrace.

By definition, no one has the legal right to enter the U.S. illegally, but according to our constitution, everyone in America is entitled to due process.

Renewable Energy

Cancelling Renewable Energy

This will result in lung disease, climate change, loss of biodiversity, and higher electricity prices.

This will result in lung disease, climate change, loss of biodiversity, and higher electricity prices.

It will also further alienate the rest of the world from our country, as every other nation on the planet is making gains in the direction of decarbonization, and no other nation suffers from this level of corruption with the fossil fuel industry.

If that pleases you, you’re a warped human being.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits