The year 2024 was marked by violence and elections, as conflicts escalated around the world and billions of voters went to the polls.

However, climate change still made headlines.

Thousands of peer-reviewed journal articles were published over the course of the year, helping shape online discourse around climate change.

Tracking these mentions was Altmetric, an organisation that scores research papers according to the attention they receive online.

To do this, it tracks how often published peer-reviewed research is mentioned online in news articles, as well as on blogs, Wikipedia and on social media platforms such as Facebook, Reddit, Twitter and – in a new addition for 2024 – Bluesky. (Carbon Brief explained how Altmetric’s scoring system works in this article.)

Carbon Brief has parsed the data to compile its annual list of the 25 most talked-about climate-related papers of the past year.

The infographic above highlights the most mentioned climate papers of 2024, while the article analyses the top 25 research papers in greater detail, including the diversity and country affiliation of authors.

Overall, Altmetric’s data reveals the papers which generated the most online buzz in 2024 were – for the fourth year running – associated with Covid-19, with five of the 10 most talked-about papers of the year related to the virus.

However, a number of the most-shared studies were about climate change, from how warming is impacting ocean currents, the economy and timekeeping, through to efforts aimed at mapping historical temperatures using proxy data.

A return from last year’s highs

After a blockbuster year for online mentions of climate science in 2023, last year saw a return to more typical levels.

The most widely shared climate paper of 2024 has a score of 5,414, placing it at the bottom end of the range for top climate papers over the past seven years.

By contrast, the three most talked-about climate papers of 2023 received the highest attention scores recorded across all of Carbon Brief’s annual reviews, which date back to 2015. They clocked scores of 13,886, 8,686 and 7,821.

(For Carbon Brief’s previous Altmetric articles, see the links for 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 and 2015.)

The graph below shows how the score given to the top paper in Carbon Brief’s annual review has changed over the past 10 years.

A spokesperson for Altmetric says the falling popularity of climate papers was not due to any adjustments to its methodology, noting that its scoring system “had not changed”. They tell Carbon Brief that online mentions of papers – across all disciplines – have declined in recent years from a peak in 2020, resulting in lower average scores across the board.

The spokesperson said it was unclear why the average number of mentions had fallen since 2020, but hypothesised that several factors could be at play. This includes a surge of policy citations during the Covid-19 pandemic and changes in how people use social media – such as a decline in posts on public Facebook feeds and a spike in Twitter posts in 2021.

The top 10 climate papers of 2024

- Physics-based early warning signal shows that AMOC is on tipping course

- The economic commitment of climate change

- 2023 summer warmth unparalleled over the past 2,000 years

- The growing inadequacy of an open-ended Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale in a warming world

- Critical transitions in the Amazon forest system

- Highest ocean heat in four centuries places Great Barrier Reef in danger

- Abrupt reduction in shipping emission as an inadvertent geoengineering termination shock produces substantial radiative warming

- A global timekeeping problem postponed by global warming

- Accelerating glacier volume loss on Juneau Icefield driven by hypsometry and melt-accelerating feedbacks

- A 485-million-year history of Earth’s surface temperature

Later in this article, Carbon Brief looks at the rest of the top 25, and provides analysis of the most featured journals, as well as the gender diversity and country of origin of authors.

AMOC alarm

The most talked-about climate paper of 2024 is a Science Advances study that finds the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) – a system of ocean currents that brings warm water up to Europe from the tropics and beyond – is “on route to tipping”.

The research, titled “Physics-based early warning signal shows that AMOC is on tipping course”, marks the first time that an AMOC tipping event has been identified in a cutting-edge climate model, in this case the Community Earth System Model.

The study’s Altmetric score of 5,414 shoots it to the top of Carbon Brief’s leaderboard and 1,272 points ahead of the second-placed paper.

However, as illustrated in the graph above, the research is the lowest-scoring climate paper to reach the top of the leaderboard since 2017.

The researchers from the Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research Utrecht describe the paper’s finding as “bad news for the climate system and humanity”. They explain:

“Up until now one could think that AMOC tipping was only a theoretical concept and tipping would disappear as soon as the full climate system, with all its additional feedbacks, was considered.”

The study paints a grisly picture of the consequences of a collapse of AMOC. This includes a 10-30C drop in winter temperatures in northern Europe within a century, and a “drastic change” in rainfall patterns in the Amazon. The paper states:

“These – and many more – impacts of an AMOC collapse have been known for a long time, but thus far have not been shown in a climate model of such high quality.”

Papers exploring the stability of AMOC have dominated Carbon Brief’s climate science leaderboard in recent years, coming in fourth and second place, respectively, in 2023 and 2021.

Media coverage has been amplified by disagreement over what metrics to use to measure the strength of AMOC. Previous studies have used sea surface temperature to make projections about when the tipping point may occur.

The Science Advances paper reaches its conclusions using a new, “physics-based” early warning signal for the breakdown of the vital ocean currents based on the salinity of water in the southern Atlantic.

Overall, the study racked up 601 news mentions, with the Times, Guardian, Daily Telegraph, Associated Press and CNN all reporting on its findings. It was also featured in 39 blogs, the highest of any paper in the top 25, and was shared more than 3,866 times on Twitter.

Study author Dr René van Westen tells Carbon Brief he believes the paper owes its popularity to its alarming conclusion that AMOC is approaching a tipping point, as well as the detail it offers around the “large-scale changes” and “substantial” climate impacts such an event could trigger. He explains:

“The urgency of the situation, suggesting that we are heading toward this collapse, underscores the need for immediate action to prevent such a scenario. We believe that the combination of these far-reaching climate impacts and the risk of AMOC collapse contributed to the extensive media coverage of our study.”

Economic commitment

The second highest-scoring climate paper of 2024, published in the journal Nature, is “The economic commitment of climate change”. The study has an Altmetric score of 4,142 and clocks in at second in the 2024 rankings.

The three-person authorship team, from Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, used 40 years of data on damages from temperature and rainfall from more than 1,600 regions around the world to assess how damages could increase under a warming climate.

They estimate that the world economy is committed to an income reduction of 19% within the next 26 years, regardless of how rapidly humanity now cuts emissions. These damages are six times higher than the mitigation costs required to limit global warming to 2C in the near term, the authors say.

They also warn that climate change is likely to exacerbate existing inequalities, adding:

“The largest losses are committed at lower latitudes in regions with lower cumulative historical emissions and lower present-day income.”

The study was mentioned 55 times on Bluesky. It has also been cited by Wikipedia seven times, including in pages on climate justice and climate change mitigation.

The study’s lead author, Dr Maximilian Kotz, tells Carbon Brief:

“We think we made a helpful contribution by pushing the limits of the spatial scales, climate information and assumptions around long-term persistence which are used in these kinds of studies.”

However, he said the media coverage mainly focused on the final numbers, speculating that “part of the wide interest in the media was likely that these numbers were large”. He told Carbon Brief that, in his experience, it is “normal for the media not to pay much attention to the kind of details a researcher finds important”.

Kotz added that since his study came out, a number of other papers have been published using different approaches, but arriving at similar final numbers.

Record hot summer

Coming in third place is a Nature paper which uses temperatures reconstructed from tree rings to conclude the northern hemisphere summer of 2023 was the hottest in two millennia.

To build a picture of summer temperatures stretching back to AD1, the researchers turn to nine of the longest temperature-sensitive tree ring chronologies in North America and Europe, as well as observational data for 1901-2010.

Rest of the top 10

In fourth place, with an Altmetric score of 3,907, is a paper that assesses whether the classification system for tropical cyclone wind speed needs to be expanded to reflect storms’ growing intensity in a warming world. It was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The research, “The growing inadequacy of an open-ended Saffir-Simpson hurricane-wind scale in a warming world”, says climate change has led to more intense storms, which could justify a new category on the Saffir-Simpson scale.

Introduced in the 1970s, the scale is used to communicate the risk tropical cyclone winds present to property. Events are ranked from category 1, for storms with winds of 74-95 miles per hour (mph), to category 5 for storms with a wind-speed of 157mph and above.

The study highlights how five tropical cyclones of the last nine years were so intense they could sit in a hypothetical sixth category, which could cover storms with winds of 192mph and above.

The study received more news coverage than any other in this year’s top 25, amassing 720 mentions.

In fifth and sixth place, with scores of 3,757 and 3,248, respectively, are a pair of Nature papers.

The first, “Critical transitions in the Amazon forest system”, finds that by 2050, 10-47% of the Amazon forest will be exposed to “compounding disturbances” that may trigger a tipping point, causing a shift from lush rainforest to dry savannah. Carbon Brief covered the study.

The second is a paper looking at how rising ocean temperatures are endangering the Great Barrier Reef. It cautions that without “urgent intervention” the world’s largest coral reef system is at risk of experiencing “temperatures conducive to near-annual coral bleaching” with negative consequences for biodiversity and ecosystem services.

The seventh-placed paper finds a reduction in sulphur emissions from ships – driven by cleaner fuel regulations introduced in 2020 – has led to “substantial radiative warming” that could lead to a “doubling (or more)” of the rate of warming this decade. (Carbon Brief published its own analysis of how low-sulphur shipping rules are affecting global warming in 2023.)

The Communications Earth & Environment study goes on to suggest that marine cloud brightening – a geoengineering technique where marine low clouds are “seeded” with aerosols – may be a “viable” climate solution.

Coming in eighth is a paper which finds that ice melt in Greenland and Antarctica is delaying an observed acceleration of Earth’s rotation, with consequences for global timekeeping.

The Nature paper, “A global timekeeping problem postponed by global warming”, finds the redistribution of mass on Earth as polar ice melts means timekeepers will have to remove a second from global clocks around 2029. If it were not for the acceleration in polar ice melt, this second would have been due for removal by 2026, it says.

Timekeepers are no strangers to tweaking time to adjust for the Earth’s rotation; 27 leap seconds have been added to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) since the 1970s. However, the paper cautions the first-ever removal of a second is set to pose “an unprecedented problem” for computer network timing.

(Similarly, in 25th place is a Proceedings of the National Academy of Science paper that finds melting ice sheets and glaciers are redistributing the planet’s mass, causing days to become longer by milliseconds.)

In ninth place is a Nature Communications paper which finds that rates of glacier area shrinkage on the Juneau ice field, which straddles Alaska and British Columbia, were five times faster over 2015-19 relative to 1948-79.

Rounding out the top 10 is a Science study that uses proxy data to conclude that the Earth’s average surface temperature has varied between 11C and 36C over the past 485m years.

Retracted papers go viral

One of the most shared papers of the year looks into a CO2 “saturation hypothesis” – a popular topic among climate sceptics. The theory contends the atmosphere has reached a CO2 saturation point, which means that additional emissions of the gas will cause little or no further warming.

The paper argues “continued and improved experimental work” is needed to ascertain whether “additionally emitted carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is indeed a greenhouse gas”.

The research, entitled “Climatic consequences of the process of saturation of radiation absorption in gases”, was published by Applications in Engineering Science in March, but subsequently retracted by the editor.

In a retraction notice, Applications in Engineering Science said the rigour and quality of the peer-review process for the paper had been “investigated and confirmed to fall beneath the high standards expected”.

While the paper received just four news mentions, it was widely shared on Twitter, clocking more than 6,000 posts. With a score of 2,661, it would have been the ninth most talked-about climate paper of 2024 had it not been retracted.

UK political commentator and climate sceptic Toby Young, who was recently promoted to the UK House of Lords, shared an article promoting saturation theory in late December that references the research. As of 9 January, his Twitter post had been shared 6,500 times and viewed 128,300 times.

Controversial Covid-19 treatment and vaccination research also received significant attention in 2024, with four of the most talked-about papers of the year – of any topic – retracted by journal editors.

The studies in question – three of which relate to vaccines and one to hydroxychloroquine – would have placed first, third, fourth and sixth in Altmetric’s overall rankings, had they not been withdrawn.

A controversial paper that did make it into the top 25 without being retracted was a study in the journal Geomatics. It argues that a decrease in planetary albedo and variations in “total solar irradiance” explain “100% of the global warming trend” over 2000-23 and 83% of interannual variability in global temperatures.

The authors have previously proposed a theory that global warming is caused by atmospheric pressure – and were caught publishing their papers under pseudonyms, which were their own names spelled backwards.

With only four news mentions, most of the attention from this article came from other sources. A tweet from the study’s lead author prompted a heated discussion and generated thousands of likes and retweets. Overall, the research was mentioned on Twitter 9,599 times.

The study, which came 13th in the overall rankings with a score of 2,096, was also mentioned on 14 blogs, including a number of climate-sceptic websites.

Elsewhere in the top 25

The rest of the top 25 contains a varied mix of papers that were typically well-received by the scientific community, including research on oil and gas system emissions (15th), mortality due to tropical cyclones in the US (16th) and the latest “state of wildfires” update (22nd).

Paper number 12 finds that a “record-low planetary albedo”, mainly caused by low cloud cover in the northern mid-latitudes and tropics, may have been an important driver of the record-high global temperatures in 2023.

Published on 5 December in the journal Science, it is a relatively late entry into the annual rankings. Despite its late publication date, the study tops the charts for Bluesky mentions, gaining 376 mentions in less than one month.

A Communications Earth & Environment study, called “A recent surge in global warming is not detectable yet”, sits at number 21, with an Altmetric score of 2,018. The study uses statistical methods to search for a recent acceleration in global warming, and concludes that it is not possible to detect one.

The lead author of the study told Carbon Brief that the findings do not rule out that an acceleration might be occurring. She said that “the point of the paper is that it will take additional years of observations to detect a sustained acceleration”. However, some scientists questioned the utility of the methods used in the study, arguing there is evidence of an acceleration in warming.

At number 23 is a study in the journal Science which evaluates 1,500 climate policies that have been implemented over the past 25 years. The lead author of the study told Carbon Brief that taxes are “the only policy instrument that has been found to cause large emission reductions on their own”. The study received 30 mentions in blogs and more than 200 news mentions.

Some studies receive a lot of attention because they provoke discussion or a significant backlash, which drives up news stories and discussion on social media.

For example, the paper ranking at number 14 is a Nature Climate Change study claiming that the planet has already exceeded the 1.5C warming threshold set under the Paris Agreement.

The authors use proxy data from sea sponges in the Caribbean Sea to create a record of ocean temperatures from AD700 to the present day. They find that warming started 40 years before the IPCC’s pre-industrial baseline period began, and argue that this means “warming is 0.5C higher than [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] estimates”.

However, many experts were critical, warning Carbon Brief that the framing of the study is misleading, and arguing that the finding has no bearing on the Paris Agreement 1.5C limit. One expert, who was also not involved in the study, said that “the way these findings have been communicated is flawed, and has the potential to add unnecessary confusion to public debate on climate change”.

The study received 262 news mentions, with some outlets – including the Guardian and New Scientist – highlighting the disagreements over the study’s framing.

All the final scores for the top 25 climate papers of 2024 can be found in this spreadsheet.

Top journals

Across the top 25 papers in Carbon Brief’s leaderboard this year, Nature features most frequently with seven papers. Nature is perennially high-placed in this analysis, taking first or joint first spot in Carbon Brief’s top 25 six times – 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017 and 2015.

In joint-second place this year are Science, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and Communications Earth & Environment with three papers each.

Earth System Science Data has two papers, and there are seven journals that each have one paper.

Diversity of the top 25

The top 25 climate papers of 2024 cover a wide range of topics and scope. However, analysis of their authors reveals an all-too-familiar lack of diversity. Carbon Brief recorded the gender and country of affiliation for each of these authors. (The methodology used was developed by Carbon Brief for analysis presented in a special 2021 series on climate justice.)

In total, the top 25 climate papers of 2024 have 275 authors. This is fewer than in the past two years, partly due to the absence of the Lancet Countdown report, which typically has more than 100 authors.

The analysis reveals that the authors of the climate papers most featured in the media in 2024 are predominantly men from the global north.

The chart below shows the institutional affiliations of all authors in this analysis, broken down by continent – Europe, North America, Oceania, Asia, South America and Africa.

The analysis shows that 85% of authors are affiliated with institutions from the global north – defined as North America, Europe and Oceania. Meanwhile, only two authors are from Africa.

Further data analysis shows that there are also inequalities within continents. The map below shows the percentage of authors from each country in the analysis, where dark blue indicates a higher percentage. Countries that are not represented by any authors in the analysis are shown in grey.

The top-ranking countries on this map are the US and the UK, with 26% and 18% of the total authors, respectively. Germany ranks third on the list with 15% of the authors.

Meanwhile, only one-third of authors from the top 25 climate papers of 2024 are women. And only five of the 25 papers have a woman as a lead author.

The plot below shows the number of authors from each continent who are men (purple) and women (yellow).

The full spreadsheet showing the results of this data analysis can be found here. For more on the biases in climate publishing, see Carbon Brief’s article on the lack of diversity in climate-science research.

The post Analysis: The climate papers most featured in the media in 2024 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: The climate papers most featured in the media in 2024

Greenhouse Gases

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Food inflation on the rise

DELUGE STRIKES FOOD: Extreme rainfall and flooding across the Mediterranean and north Africa has “battered the winter growing regions that feed Europe…threatening food price rises”, reported the Financial Times. Western France has “endured more than 36 days of continuous rain”, while farmers’ associations in Spain’s Andalusia estimate that “20% of all production has been lost”, it added. Policy expert David Barmes told the paper that the “latest storms were part of a wider pattern of climate shocks feeding into food price inflation”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

NO BEEF: The UK’s beef farmers, meanwhile, “face a double blow” from climate change as “relentless rain forces them to keep cows indoors”, while last summer’s drought hit hay supplies, said another Financial Times article. At the same time, indoor growers in south England described a 60% increase in electricity standing charges as a “ticking timebomb” that could “force them to raise their prices or stop production, which will further fuel food price inflation”, wrote the Guardian.

‘TINDERBOX’ AND TARIFFS: A study, covered by the Guardian, warned that major extreme weather and other “shocks” could “spark social unrest and even food riots in the UK”. Experts cited “chronic” vulnerabilities, including climate change, low incomes, poor farming policy and “fragile” supply chains that have made the UK’s food system a “tinderbox”. A New York Times explainer noted that while trade could once guard against food supply shocks, barriers such as tariffs and export controls – which are being “increasingly” used by politicians – “can shut off that safety valve”.

El Niño looms

NEW ENSO INDEX: Researchers have developed a new index for calculating El Niño, the large-scale climate pattern that influences global weather and causes “billions in damages by bringing floods to some regions and drought to others”, reported CNN. It added that climate change is making it more difficult for scientists to observe El Niño patterns by warming up the entire ocean. The outlet said that with the new metric, “scientists can now see it earlier and our long-range weather forecasts will be improved for it.”

WARMING WARNING: Meanwhile, the US Climate Prediction Center announced that there is a 60% chance of the current La Niña conditions shifting towards a neutral state over the next few months, with an El Niño likely to follow in late spring, according to Reuters. The Vibes, a Malaysian news outlet, quoted a climate scientist saying: “If the El Niño does materialise, it could possibly push 2026 or 2027 as the warmest year on record, replacing 2024.”

CROP IMPACTS: Reuters noted that neutral conditions lead to “more stable weather and potentially better crop yields”. However, the newswire added, an El Niño state would mean “worsening drought conditions and issues for the next growing season” to Australia. El Niño also “typically brings a poor south-west monsoon to India, including droughts”, reported the Hindu’s Business Line. A 2024 guest post for Carbon Brief explained that El Niño is linked to crop failure in south-eastern Africa and south-east Asia.

News and views

- DAM-AG-ES: Several South Korean farmers filed a lawsuit against the country’s state-owned utility company, “seek[ing] financial compensation for climate-related agricultural damages”, reported United Press International. Meanwhile, a national climate change assessment for the Philippines found that the country “lost up to $219bn in agricultural damages from typhoons, floods and droughts” over 2000-10, according to Eco-Business.

- SCORCHED GRASS: South Africa’s Western Cape province is experiencing “one of the worst droughts in living memory”, which is “scorching grass and killing livestock”, said Reuters. The newswire wrote: “In 2015, a drought almost dried up the taps in the city; farmers say this one has been even more brutal than a decade ago.”

- NOUVELLE VEG: New guidelines published under France’s national food, nutrition and climate strategy “urged” citizens to “limit” their meat consumption, reported Euronews. The delayed strategy comes a month after the US government “upended decades of recommendations by touting consumption of red meat and full-fat dairy”, it noted.

- COURTING DISASTER: India’s top green court accepted the findings of a committee that “found no flaws” in greenlighting the Great Nicobar project that “will lead to the felling of a million trees” and translocating corals, reported Mongabay. The court found “no good ground to interfere”, despite “threats to a globally unique biodiversity hotspot” and Indigenous tribes at risk of displacement by the project, wrote Frontline.

- FISH FALLING: A new study found that fish biomass is “falling by 7.2% from as little as 0.1C of warming per decade”, noted the Guardian. While experts also pointed to the role of overfishing in marine life loss, marine ecologist and study lead author Dr Shahar Chaikin told the outlet: “Our research proves exactly what that biological cost [of warming] looks like underwater.”

- TOO HOT FOR COFFEE: According to new analysis by Climate Central, countries where coffee beans are grown “are becoming too hot to cultivate them”, reported the Guardian. The world’s top five coffee-growing countries faced “57 additional days of coffee-harming heat” annually because of climate change, it added.

Spotlight

Nature talks inch forward

This week, Carbon Brief covers the latest round of negotiations under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which occurred in Rome over 16-19 February.

The penultimate set of biodiversity negotiations before October’s Conference of the Parties ended in Rome last week, leaving plenty of unfinished business.

The CBD’s subsidiary body on implementation (SBI) met in the Italian capital for four days to discuss a range of issues, including biodiversity finance and reviewing progress towards the nature targets agreed under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

However, many of the major sticking points – particularly around finance – will have to wait until later this summer, leaving some observers worried about the capacity for delegates to get through a packed agenda at COP17.

The SBI, along with the subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) will both meet in Nairobi, Kenya, later this summer for a final round of talks before COP17 kicks off in Yerevan, Armenia, on 19 October.

Money talks

Finance for nature has long been a sticking point at negotiations under the CBD.

Discussions on a new fund for biodiversity derailed biodiversity talks in Cali, Colombia, in autumn 2024, requiring resumed talks a few months later.

Despite this, finance was barely on the agenda at the SBI meetings in Rome. Delegates discussed three studies on the relationship between debt sustainability and implementation of nature plans, but the more substantive talks are set to take place at the next SBI meeting in Nairobi.

Several parties “highlighted concerns with the imbalance of work” on finance between these SBI talks and the next ones, reported Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Lim Li Ching, senior researcher at Third World Network, noted that tensions around finance permeated every aspect of the talks. She told Carbon Brief:

“If you’re talking about the gender plan of action – if there’s little or no financial resources provided to actually put it into practice and implement it, then it’s [just] paper, right? Same with the reporting requirements and obligations.”

Monitoring and reporting

Closely linked to the issue of finance is the obligations of parties to report on their progress towards the goals and targets of the GBF.

Parties do so through the submission of national reports.

Several parties at the talks pointed to a lack of timely funding for driving delays in their reporting, according to ENB.

A note released by the CBD Secretariat in December said that no parties had submitted their national reports yet; by the time of the SBI meetings, only the EU had. It further noted that just 58 parties had submitted their national biodiversity plans, which were initially meant to be published by COP16, in October 2024.

Linda Krueger, director of biodiversity and infrastructure policy at the environmental not-for-profit Nature Conservancy, told Carbon Brief that despite the sparse submissions, parties are “very focused on the national report preparation”. She added:

“Everybody wants to be able to show that we’re on the path and that there still is a pathway to getting to 2030 that’s positive and largely in the right direction.”

Watch, read, listen

NET LOSS: Nigeria’s marine life is being “threatened” by “ghost gear” – nets and other fishing equipment discarded in the ocean – said Dialogue Earth.

COMEBACK CAUSALITY: A Vox long-read looked at whether Costa Rica’s “payments for ecosystem services” programme helped the country turn a corner on deforestation.

HOMEGROWN GOALS: A Straits Times podcast discussed whether import-dependent Singapore can afford to shelve its goal to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030.

‘RUSTING’ RIVERS: The Financial Times took a closer look at a “strange new force blighting the [Arctic] landscape”: rivers turning rust-orange due to global warming.

New science

- Lakes in the Congo Basin’s peatlands are releasing carbon that is thousands of years old | Nature Geoscience

- Natural non-forest ecosystems – such as grasslands and marshlands – were converted for agriculture at four times the rate of land with tree cover between 2005 and 2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Around one-quarter of global tree-cover loss over 2001-22 was driven by cropland expansion, pastures and forest plantations for commodity production | Nature Food

In the diary

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean | Brasília

- 5 March: Nepal general elections

- 9-20 March: First part of the thirty-first session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) | Kingston, Jamaica

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

Greenhouse Gases

Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’

Rising temperatures across France since the mid-1970s is putting Tour de France competitors at “high risk”, according to new research.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, uses 50 years of climate data to calculate the potential heat stress that athletes have been exposed to across a dozen different locations during the world-famous cycling race.

The researchers find that both the severity and frequency of high-heat-stress events have increased across France over recent decades.

But, despite record-setting heatwaves in France, the heat-stress threshold for safe competition has rarely been breached in any particular city on the day the Tour passed through.

(This threshold was set out by cycling’s international governing body in 2024.)

However, the researchers add it is “only a question of time” until this occurs as average temperatures in France continue to rise.

The lead author of the study tells Carbon Brief that, while the race organisers have been fortunate to avoid major heat stress on race days so far, it will be “harder and harder to be lucky” as extreme heat becomes more common.

‘Iconic’

The Tour de France is one of the world’s most storied cycling races and the oldest of Europe’s three major multi-week cycling competitions, or Grand Tours.

Riders cover around 3,500 kilometres (km) of distance and gain up to nearly 55km of altitude over 21 stages, with only two or three rest days throughout the gruelling race.

The researchers selected the Tour de France because it is the “iconic bike race. It is the bike race of bike races,” says Dr Ivana Cvijanovic, a climate scientist at the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development, who led the new work.

Heat has become a growing problem for the competition in recent years.

In 2022, Alexis Vuillermoz, a French competitor, collapsed at the finish line of the Tour’s ninth stage, leaving in an ambulance and subsequently pulling out of the race entirely.

Two years later, British cyclist Sir Mark Cavendish vomited on his bike during the first stage of the race after struggling with the 36C heat.

The Tour also makes a good case study because it is almost entirely held during the month of July and, while the route itself changes, there are many cities and stages that are repeated from year to year, Cvijanovic adds.

‘Have to be lucky’

The study focuses on the 50-year span between 1974 and 2023.

The researchers select six locations across the country that have commonly hosted the Tour, from the mountain pass of Col du Tourmalet, in the French Pyrenees, to the city of Paris – where the race finishes, along the Champs-Élysées.

These sites represent a broad range of climatic zones: Alpe d’ Huez, Bourdeaux, Col du Tourmalet, Nîmes, Paris and Toulouse.

For each location, they use meteorological reanalysis data from ERA5 and radiant temperature data from ERA5-HEAT to calculate the “wet-bulb globe temperature” (WBGT) for multiple times of day across the month of July each year.

WBGT is a heat-stress index that takes into account temperature, humidity, wind speed and direct sunlight.

Although there is “no exact scientific consensus” on the best heat-stress index to use, WBGT is “one of the rare indicators that has been originally developed based on the actual human response to heat”, Cvijanovic explains.

It is also the one that the International Cycling Union (UCI) – the world governing body for sport cycling – uses to assess risk. A WBGT of 28C or higher is classified as “high risk” by the group.

WBGT is the “gold standard” for assessing heat stress, says Dr Jessica Murfree, director of the ACCESS Research Laboratory and assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Murfree, who was not involved in the new study, adds that the researchers are “doing the right things by conducting their science in alignment with the business practices that are already happening”.

The researchers find that across the 50-year time period, WBGT has been increasing across the entire country – albeit, at different rates. In the north-west of the country, WBGT has increased at an average rate of 0.1C per decade, while in the southern and eastern parts of the country, it has increased by more than 0.5C per decade.

The maps below show the maximum July WBGT for each decade of the analysis (rows) and for hourly increments of the late afternoon (columns). Lower temperatures are shown in lighter greens and yellows, while higher temperatures are shown in darker reds and purples.

Six Tour de France locations analysed in the study are shown as triangles on the maps (clockwise from top): Paris, Alpe d’ Huez, Nîmes, Toulouse, Col du Tourmalet and Bordeaux.

The maps show that the maximum WBGT temperature in the afternoon has surpassed 28C over almost the entire country in the last decade. The notable exceptions to this are the mountainous regions of the Alps and the Pyrenees.

The researchers also find that most of the country has crossed the 28C WBGT threshold – which they describe as “dangerous heat levels” – on at least one July day over the past decade. However, by looking at the WBGT on the day the Tour passed through any of these six locations, they find that the threshold has rarely been breached during the race itself.

For example, the research notes that, since 1974, Paris has seen a WBGT of 28C five times at 3pm in July – but that these events have “so far” not coincided with the cycling race.

The study states that it is “fortunate” that the Tour has so far avoided the worst of the heat-stress.

Cvijanovic says the organisers and competitors have been “lucky” to date. She adds:

“It has worked really well for them so far. But as the frequency of these [extreme heat] events is increasing, it will be harder and harder to be lucky.”

Dr Madeleine Orr, an assistant professor of sport ecology at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that the paper was “really well done”, noting that its “methods are good [and its] approach was sound”. She adds:

“[The Tour has] had athletes complain about [the heat]. They’ve had athletes collapse – and still those aren’t the worst conditions. I think that that says a lot about what we consider safe. They’ve still been lucky to not see what unsafe looks like, despite [the heat] having already had impacts.”

Heat safety protocols

In 2024, the UCI set out its first-ever high temperature protocol – a set of guidelines for race organisers to assess athletes’ risk of heat stress.

The assessment places the potential risk into one of five categories based on the WBGT, ranging from very low to high risk.

The protocol then sets out suggested actions to take in the event of extreme heat, ranging from having athletes complete their warm-ups using ice vests and cold towels to increasing the number of support vehicles providing water and ice.

If the WBGT climbs above the 28C mark, the protocol suggests that organisers modify the start time of the stage, adapt the course to remove particularly hazardous sections – or even cancel the race entirely.

However, Orr notes that many other parts of the race, such as spectator comfort and equipment functioning, may have lower temperatures thresholds that are not accounted for in the protocol, but should also be considered.

Murfree points out that the study’s findings – and the heat protocol itself – are “really focused on adaptation, rather than mitigation”. While this is “to be expected”, she tells Carbon Brief:

“Moving to earlier start times or adjusting the route specifically to avoid these locations that score higher in heat stress doesn’t stop the heat stress. These aren’t climate preventative measures. That, I think, would be a much more difficult conversation to have in the research because of the Tour de France’s intimate relationship with fossil-fuel companies.”

The post Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Preparing for 3C

NEW ALERT: The EU’s climate advisory board urged countries to prepare for 3C of global warming, reported the Guardian. The outlet quoted Maarten van Aalst, a member of the advisory board, saying that adapting to this future is a “daunting task, but, at the same time, quite a doable task”. The board recommended the creation of “climate risk assessments and investments in protective measures”.

‘INSUFFICIENT’ ACTION: EFE Verde added that the advisory board said that the EU’s adaptation efforts were so far “insufficient, fragmented and reactive” and “belated”. Climate impacts are expected to weaken the bloc’s productivity, put pressure on public budgets and increase security risks, it added.

UNDERWATER: Meanwhile, France faced “unprecedented” flooding this week, reported Le Monde. The flooding has inundated houses, streets and fields and forced the evacuation of around 2,000 people, according to the outlet. The Guardian quoted Monique Barbut, minister for the ecological transition, saying: “People who follow climate issues have been warning us for a long time that events like this will happen more often…In fact, tomorrow has arrived.”

IEA ‘erases’ climate

MISSING PRIORITY: The US has “succeeded” in removing climate change from the main priorities of the International Energy Agency (IEA) during a “tense ministerial meeting” in Paris, reported Politico. It noted that climate change is not listed among the agency’s priorities in the “chair’s summary” released at the end of the two-day summit.

US INTERVENTION: Bloomberg said the meeting marked the first time in nine years the IEA failed to release a communique setting out a unified position on issues – opting instead for the chair’s summary. This came after US energy secretary Chris Wright gave the organisation a one-year deadline to “scrap its support of goals to reduce energy emissions to net-zero” – or risk losing the US as a member, according to Reuters.

Around the world

- ISLAND OBJECTION: The US is pressuring Vanuatu to withdraw a draft resolution supporting an International Court of Justice ruling on climate change, according to Al Jazeera.

- GREENLAND HEAT: The Associated Press reported that Greenland’s capital Nuuk had its hottest January since records began 109 years ago.

- CHINA PRIORITIES: China’s Energy Administration set out its five energy priorities for 2026-2030, including developing a renewable energy plan, said International Energy Net.

- AMAZON REPRIEVE: Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has continued to fall into early 2026, extending a downward trend, according to the latest satellite data covered by Mongabay.

- GEZANI DESTRUCTION: Reuters reported the aftermath of the Gezani cyclone, which ripped through Madagascar last week, leaving 59 dead and more than 16,000 displaced people.

20cm

The average rise in global sea levels since 1901, according to a Carbon Brief guest post on the challenges in projecting future rises.

Latest climate research

- Wildfire smoke poses negative impacts on organisms and ecosystems, such as health impacts on air-breathing animals, changes in forests’ carbon storage and coral mortality | Global Ecology and Conservation

- As climate change warms Antarctica throughout the century, the Weddell Sea could see the growth of species such as krill and fish and remain habitable for Emperor penguins | Nature Climate Change

- About 97% of South American lakes have recorded “significant warming” over the past four decades and are expected to experience rising temperatures and more frequent heatwaves | Climatic Change

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

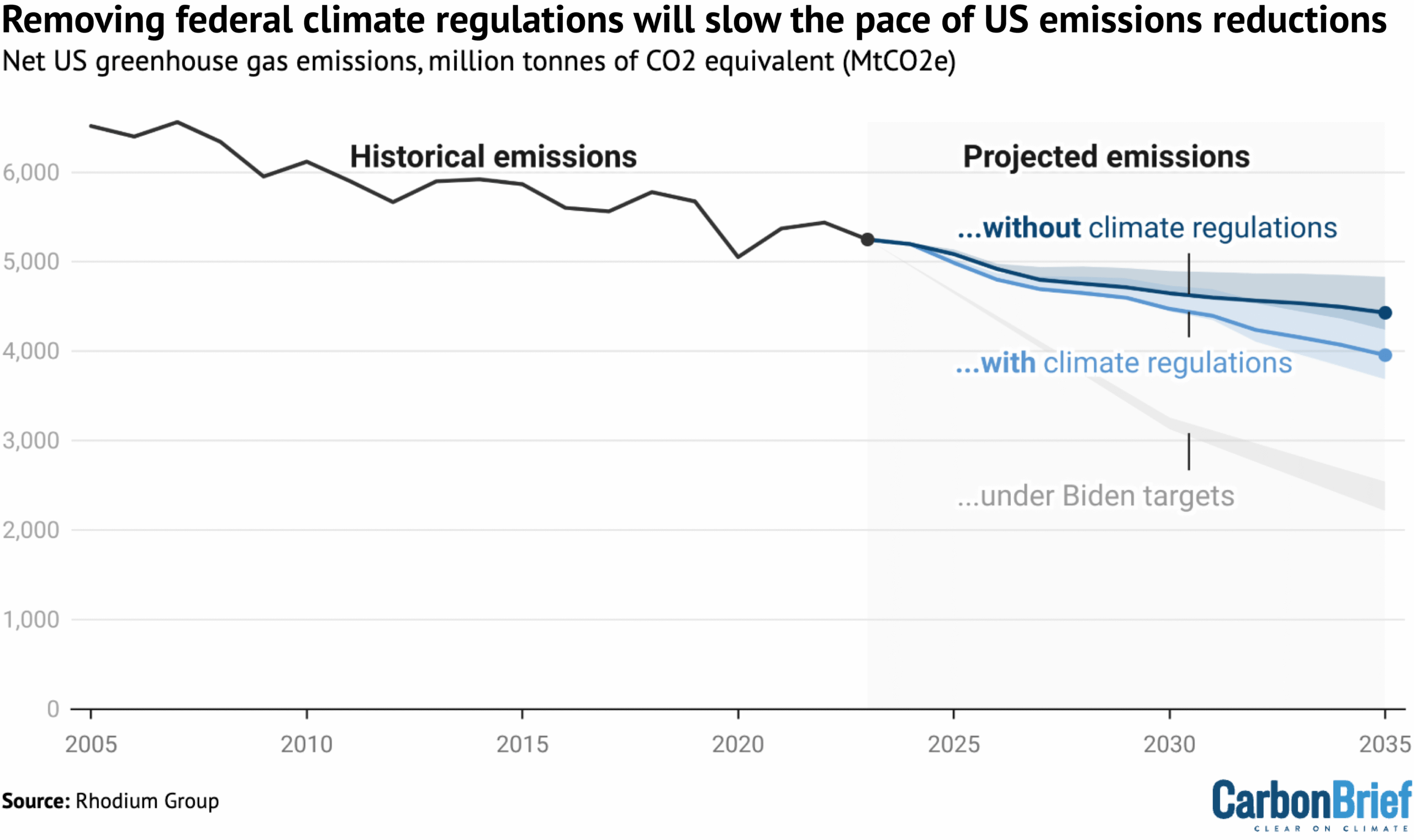

Repealing the US’s landmark “endangerment finding”, along with actions that rely on that finding, will slow the pace of US emissions cuts, according to Rhodium Group visualised by Carbon Brief. US president Donald Trump last week formally repealed the scientific finding that underpins federal regulations on greenhouse gas emissions, although the move is likely to face legal challenges. Data from the Rhodium Group, an independent research firm, shows that US emissions will drop more slowly without climate regulations. However, even with climate regulations, emissions are expected to drop much slower under Trump than under the previous Joe Biden administration, according to the analysis.

Spotlight

How a ‘tree invasion’ helped to fuel South America’s fires

This week, Carbon Brief explores how the “invasion” of non-native tree species helped to fan the flames of forest fires in Argentina and Chile earlier this year.

Since early January, Chile and Argentina have faced large-scale and deadly wildfires, including in Patagonia, which spans both countries.

These fires have been described as “some of the most significant and damaging in the region”, according to a World Weather Attribution (WWA) analysis covered by Carbon Brief.

In both countries, the fires destroyed vast areas of native forests and grasslands, displacing thousands of people. In Chile, the fires resulted in 23 deaths.

Multiple drivers contributed to the spread of the fires, including extended periods of high temperatures, low rainfall and abundant dry vegetation.

The WWA analysis concluded that human-caused climate change made these weather conditions at least three times more likely.

According to the researchers, another contributing factor was the invasion of non-native trees in the regions where the fires occurred.

The risk of non-native forests

In Argentina, the wildfires began on 6 January and persisted until the first week of February. They hit the city of Puerto Patriada and the Los Alerces and Lago Puelo national parks, in the Chubut province, as well as nearby regions.

In these areas, more than 45,000 hectares of native forests – such as Patagonian alerce tree, myrtle, coigüe and ñire – along with scrubland and grasslands, were consumed by the flames, according to the WWA study.

In Chile, forest fires occurred from 17 to 19 January in the Biobío, Ñuble and Araucanía regions.

The fires destroyed more than 40,000 hectares of forest and more than 20,000 hectares of non-native forest plantations, including eucalyptus and Monterey pine.

Dr Javier Grosfeld, a researcher at Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in northern Patagonia, told Carbon Brief that these species, introduced to Patagonia for production purposes in the late 20th century, grow quickly and are highly flammable.

Because of this, their presence played a role in helping the fires to spread more quickly and grow larger.

However, that is no reason to “demonise” them, he stressed.

Forest management

For Grosfeld, the problem in northern Patagonia, Argentina, is a significant deficit in the management of forests and forest plantations.

This management should include pruning branches from their base and controlling the spread of non-native species, he added.

A similar situation is happening in Chile, where management of pine and eucalyptus plantations is not regulated. This means there are no “firebreaks” – gaps in vegetation – in place to prevent fire spread, Dr Gabriela Azócar, a researcher at the University of Chile’s Centre for Climate and Resilience Research (CR2), told Carbon Brief.

She noted that, although Mapuche Indigenous communities in central-south Chile are knowledgeable about native species and manage their forests, their insight and participation are not recognised in the country’s fire management and prevention policies.

Grosfeld stated:

“We are seeing the transformation of the Patagonian landscape from forest to scrubland in recent years. There is a lack of preventive forestry measures, as well as prevention and evacuation plans.”

Watch, read, listen

FUTURE FURNACE: A Guardian video explored the “unbearable experience of walking in a heatwave in the future”.

THE FUN SIDE: A Channel 4 News video covered a new wave of climate comedians who are using digital platforms such as TikTok to entertain and raise awareness.

ICE SECRETS: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast explored how scientists study ice cores to understand what the climate was like in ancient times and how to use them to inform climate projections.

Coming up

- 22-27 February: Ocean Sciences Meeting, Glasgow

- 24-26 February: Methane Mitigation Europe Summit 2026, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 25-27 February: World Sustainable Development Summit 2026, New Delhi, India

Pick of the jobs

- The Climate Reality Project, digital specialist | Salary: $60,000-$61,200. Location: Washington DC

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), science officer in the IPCC Working Group I Technical Support Unit | Salary: Unknown. Location: Gif-sur-Yvette, France

- Energy Transition Partnership, programme management intern | Salary: Unknown. Location: Bangkok, Thailand

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires appeared first on Carbon Brief.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits