The installation of solar panels and heat pumps in UK homes soared in 2023, driving the country to its highest-ever level of domestic low-carbon technology upgrades.

Registered solar photovoltaic (PV) installations rose nearly 30% to a post-subsidy record of 189,826 in 2023, according to the Microgeneration Certification Scheme (MCS).

Similarly, heat-pump installations were up 20%, reaching a record 36,799.

This growth drove a UK record for the total number of domestic renewable electricity and low-carbon heat technologies installations registered by MCS, which reached 229,618.

This brings the total MCS-certified installations of solar PV overall to 1,441,753 since 2009, equivalent to more than 5% of all UK households.

The near-record figure for home solar in 2023 is particularly significant because it came without any government support, whereas previous growth was driven by deadlines under the Feed-in-Tariff (FiT) subsidy scheme, which ended in 2019.

Below, Carbon Brief looks at MCS’s installation figures for 2023, picking out some of the most significant domestic developments.

Record clean energy growth

The UK had already recorded its “best-ever” year for renewable energy and low-carbon heat installations before 2023 came to end, as Solar Power Portal reported in December.

While solar PV and air-source heat pumps (ASHP) saw growth in their installation rates in 2023, other clean technologies dropped off somewhat.

By the end of the year, a record total of 229,618 MCS certified installations had been registered (there is the potential for a small change to the total, due to a lag with registrations, MCS told Carbon Brief).

This included a post-subsidy record 189,826 solar PV installations, up by a third from the 138,020 seen in 2022.

Solar Energy UK chief executive Chris Hewett said in a statement:

“Setting a post-subsidy record of almost 190,000 smaller-scale solar PV installations, and approaching the all-time record of 203,000, is truly a moment to celebrate. The solar industry is on a roll, particularly as we start to conclude work on the government-industry Solar Taskforce, whose roadmap for delivering 70GW [gigawatts] of capacity is due to be published in a couple of months.”

The number of MCS-registered ASHP installations grew to a record 36,799 in 2023 from 29,490 a year earlier. (The real number of heat pumps installed in the UK is likely to be higher, as there is currently no mandate for all low-carbon technology deployments to be certified, or reported in a single place.)

Bean Beanland, director for growth at trade association the Heat Pump Federation, tells Carbon Brief the growth in demand for ASHPs was being driven by increasing activity from “early movers”, as well as by the boiler upgrade scheme (BUS) subsidy, which was introduced in 2022 and increased in 2023.

The BUS initially offered a £5,000 grant for those installing an ASHP or biomass boiler and £6,000 for a ground-source heat pump (GSHP). This was raised to £7,500 for both ASHPs and GSHPs in October 2023.

Beanland adds:

“[Following the increase in the grant] one of our members went back to all the consumers who they had quoted during 2023, detailing the increase, but where they had not converted the opportunity. The result was a significant number of contracts, so the additional £2,500 has certainly made a difference.

“In parallel, the whole visibility of the technology is being driven by the likes of Octopus, Good Energy and OVO, with their very high-profile campaigns and the advent of time-of-use tariffs that improve the financial benefits considerably.”

Customers who are able to afford to deploy solar PV, a battery and a heat pump can use such tariffs to reduce operational cost, allowing the heat pump to compete with gas, he adds.

The number of GSHP installations fell from 3,420 to 2,469, while solar-thermal installations nearly halved, falling from 615 to 311.

Beanland says:

“The value of the BUS for ground-source is just far too low. Government has made a conscious decision to go for numbers rather than the highest efficiency by supporting air-source to a much greater extent. This has been compounded now that the BUS levels for air- and ground- are the same.”

The surge in ASHP means that low-carbon heating technologies still saw an overall increase in 2023, rising by 20% year-on-year, as reported by BusinessGreen.

Despite this growth, however, the installation of heat pumps remains a long way from hitting the UK government target of 600,000 installations per year by 2028.

While the MCS dashboard does not provide data on battery storage installations, a recent release from the company states that 2023 was a record-breaking year for the technology. MCS says batteries were the third most popular technology type to be installed in homes by its certified contractor base.

Of the 4,700 certified batteries registered with MCS, 4,400 were installed in 2023, it adds.

With the energy price cap on average domestic energy bills now sitting below £2,000 per year and installation costs having increased with inflation, it is unclear whether the high levels of solar PV installations in 2023 will be maintained this year.

Solar Energy UK’s chief communications officer Gareth Simkins says:

“Speculation is always a dangerous game. I think it is reasonable for current deployment rates – around 15,000 a month – to continue. This will not just be retrofits of course – we expect more newbuild homes to carry solar, too.”

Monthly solar installations hit highs

Last year saw monthly installations of rooftop solar PV start to hit the levels seen in 2015, when government subsidies were still available, as shown by the red bars in the figure below.

March 2023 saw 20,073 registered solar PV installations, putting it in the top 10 months seen in the UK. Both 11th and 12th places were claimed by months in 2023 too, with June seeing 18,049 installations and May seeing 17,787 installations.

The rest of the top 10 installation months are dominated by 2011, 2012 and 2015. This was driven largely by subsidy deadlines, with a rush seen ahead of cuts leading to record-high installation periods.

In 2012, the FiT subsidy for solar was cut in half, reducing from 43.3p per kilowatt hour (kWh) to just 21p per kWh. This cut returns from solar electricity from around 7% to 4%, according to the Guardian.

In doing so it almost doubled the payback period for households, with some seeing their £10,000-12,000 solar panels only being in credit after 18 years rather than 10, the Guardian reported at the time.

This change followed then-climate change minister Greg Barker launching a consultation into the subsidies in an effort to avoid the industry falling victim to “boom and bust“.

Following the change, installations fell by nearly 90%, according to Department of Energy and Climate Change figures reported in the Guardian.

Installations dropped from 26,941 in March 2012 to 5,522 in April 2012, according to MCS figures, although there was a further surge later that year.

Throughout 2013, installations remained relatively subdued, growing through 2014 before peaking again in 2015. Installations hit 25,614 in December 2015, but this came ahead of further FiT reduction in February 2016, which sent “shockwaves” through the sector and saw installations drop dramatically

The FiT came to an end in 2019, with the solar export guarantee brought in 2020, which sets a minimum price for electricity exported to the grid.

Following the resulting lull in installations, domestic solar PV has once again been growing. The difference this time is that there is no underlying subsidy driving growth, with rising energy bills and longer-term falls in technology costs making the technology increasingly appealing.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Solar Energy UK’s Simkins says:

“Oddly enough, it shows the success of FiTs in creating a market for solar in the first place, with the industry now standing entirely on its own two feet without government support.”

Installation costs rise

The inflationary impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and the subsequent energy crisis led to an increase in solar technology costs in 2023.

Consequently, installation costs have risen over recent years, according to MCS. Across every month in 2023, average installation costs sat above £10,000 – the only time in more than a decade that they have reached that level, as shown in the figure below.

This has been impacted by the scale of the installations to a certain extent, with the installation cost per kilowatt (kW) seeing a more limited increase. Across 2022, the average cost of installing solar per kW was £1,804 and in 2023 this rose to £2,020.

Moreover, in some months, solar was actually cheaper per kilowatt (kW) in 2023 than in 2022, MCS data shows.

It is also worth noting that the increase in the cost of solar installations has not been as dramatic as the increase in energy bills over the past couple of years.

The energy crisis drove up domestic energy bills from late 2021, as supply chain squeezes driven in part by the Russian invasion of Ukraine sent gas prices to record highs.

As a result, the default tariff price cap for consumers jumped from £1,277 per year in the six months to March 2022, to £1,971 over that summer, and then to £3,549 over the winter of 2022.

It then surged again to £4,279 over the first quarter of 2023, before it began to fall (the energy price guarantee came into force in October 2022, superseding the rate of the price cap, and limiting domestic energy bills to £2,500 initially).

The surge in domestic energy prices highlighted the exposure of the British energy system to fluctuations in international gas markets. In doing so, it is likely it helped drive uptake of domestic solar – as shown in the figure below – as households looked to cushion themselves from potential future surges.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, solar wholesaler Midsummer’s commercial director Jamie Vaux says installation costs are now coming down.

The high installation costs and long installation lead times in 2022, were driven by demand exceeding supply, he says. With new installers entering the market and mortgage rates and inflation hitting consumer spending, this has started to ease, he adds.

Average installation prices per kW peaked at £2,111 in April 2023, before slowly falling throughout the year.

Vaux explains:

“Essentially, those who had the funds available when the energy crisis hit have already had their installations, and while many still want solar, the rate stopped climbing so steeply and the curve flattened at the same time as more installers were there to meet the demand. It has become more competitive at the installation level, and installation costs have (gradually) fallen as a result.”

There is also currently a glut of solar modules, which could help prices continue to fall and stimulate further update of solar, according to Vaux.

There is currently “a year’s worth of modules already sitting in EU warehouses, and devaluing daily”, Vaux adds, meaning top-tier modules can be bought for a fraction of prices seen in 2022.

Solar Scotland

The area with the overall highest share of households with solar PV installations since the start of MCS data in 2009 is Stirling in Scotland, where 16.7% of households have solar PV (6,994 households).

Perhaps surprisingly, given their poorer insolation rates relative to other parts of the UK, Scottish local authorities appear four times in the top 10, as shown in the figure below.

Scotland’s housing policy means it is mandatory for solar to be fitted on all new build properties, helping to boost installation rates.

In terms of installations completed during 2023, the Isle of Anglesey came out on top, with 1,083 systems added, amounting to 3.5% of households.

The top 10 for last year is dominated by Welsh and Scottish local authorities, with just one English local authority making it into the list – South Cambridgeshire in ninth place.

There are five Scottish local authorities (Dumfries and Galloway, East Lothian, Perth, Moray and Kinross and Midlothian) and four Welsh local authorities (Isle of Anglesey, Ceredigion, Powys and Pembrokeshire).

The 10 local authority areas with the lowest percentage of solar PV installations since 2009 are all in London, with Kensington and Chelsea coming out on top with just 0.4% (or 297) of households having registered solar PV installed, according to MCS.

It is worth noting that due to the density of the households in London and other major cities, they are over-represented in the lowest percentage list for solar installations.

For example, Wandsworth – which comes out as having the tenth lowest rate of just 1.1% of households having solar PV – only has 1,496 installations.

Meanwhile, Torridge in Devon – which has the eighth highest rate of installations in the UK at 12.8% – has 3,899 solar PV installations. While this is more than double the number is Wandsworth, the much larger difference in percentage terms highlights the impact of population size in each local authority area.

The same is broadly true of 2023. While the area last year with the lowest installation rate was Derry City and Strabane, with just 73 installations (0.1% of households), the bottom ten is still dominated by London boroughs, which made up eight of the list.

Detached properties are the most common when it comes to solar PV installations, with 50,8193 of the MCS registered solar PV installations since 2009 (35.2%) having been fitted on detached properties, versus 447,415 on semi-detached, 288,886 on terraced, 187,131 on flats and apartments and 10,100 on other properties.

This means detached properties – which tend to be larger, with more roof area – are over-represented in terms of their share of solar installations, as shown in the figure below.

The post Analysis: Surge in heat pumps and solar drives record for UK homes in 2023 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Surge in heat pumps and solar drives record for UK homes in 2023

Greenhouse Gases

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Food inflation on the rise

DELUGE STRIKES FOOD: Extreme rainfall and flooding across the Mediterranean and north Africa has “battered the winter growing regions that feed Europe…threatening food price rises”, reported the Financial Times. Western France has “endured more than 36 days of continuous rain”, while farmers’ associations in Spain’s Andalusia estimate that “20% of all production has been lost”, it added. Policy expert David Barmes told the paper that the “latest storms were part of a wider pattern of climate shocks feeding into food price inflation”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

NO BEEF: The UK’s beef farmers, meanwhile, “face a double blow” from climate change as “relentless rain forces them to keep cows indoors”, while last summer’s drought hit hay supplies, said another Financial Times article. At the same time, indoor growers in south England described a 60% increase in electricity standing charges as a “ticking timebomb” that could “force them to raise their prices or stop production, which will further fuel food price inflation”, wrote the Guardian.

‘TINDERBOX’ AND TARIFFS: A study, covered by the Guardian, warned that major extreme weather and other “shocks” could “spark social unrest and even food riots in the UK”. Experts cited “chronic” vulnerabilities, including climate change, low incomes, poor farming policy and “fragile” supply chains that have made the UK’s food system a “tinderbox”. A New York Times explainer noted that while trade could once guard against food supply shocks, barriers such as tariffs and export controls – which are being “increasingly” used by politicians – “can shut off that safety valve”.

El Niño looms

NEW ENSO INDEX: Researchers have developed a new index for calculating El Niño, the large-scale climate pattern that influences global weather and causes “billions in damages by bringing floods to some regions and drought to others”, reported CNN. It added that climate change is making it more difficult for scientists to observe El Niño patterns by warming up the entire ocean. The outlet said that with the new metric, “scientists can now see it earlier and our long-range weather forecasts will be improved for it.”

WARMING WARNING: Meanwhile, the US Climate Prediction Center announced that there is a 60% chance of the current La Niña conditions shifting towards a neutral state over the next few months, with an El Niño likely to follow in late spring, according to Reuters. The Vibes, a Malaysian news outlet, quoted a climate scientist saying: “If the El Niño does materialise, it could possibly push 2026 or 2027 as the warmest year on record, replacing 2024.”

CROP IMPACTS: Reuters noted that neutral conditions lead to “more stable weather and potentially better crop yields”. However, the newswire added, an El Niño state would mean “worsening drought conditions and issues for the next growing season” to Australia. El Niño also “typically brings a poor south-west monsoon to India, including droughts”, reported the Hindu’s Business Line. A 2024 guest post for Carbon Brief explained that El Niño is linked to crop failure in south-eastern Africa and south-east Asia.

News and views

- DAM-AG-ES: Several South Korean farmers filed a lawsuit against the country’s state-owned utility company, “seek[ing] financial compensation for climate-related agricultural damages”, reported United Press International. Meanwhile, a national climate change assessment for the Philippines found that the country “lost up to $219bn in agricultural damages from typhoons, floods and droughts” over 2000-10, according to Eco-Business.

- SCORCHED GRASS: South Africa’s Western Cape province is experiencing “one of the worst droughts in living memory”, which is “scorching grass and killing livestock”, said Reuters. The newswire wrote: “In 2015, a drought almost dried up the taps in the city; farmers say this one has been even more brutal than a decade ago.”

- NOUVELLE VEG: New guidelines published under France’s national food, nutrition and climate strategy “urged” citizens to “limit” their meat consumption, reported Euronews. The delayed strategy comes a month after the US government “upended decades of recommendations by touting consumption of red meat and full-fat dairy”, it noted.

- COURTING DISASTER: India’s top green court accepted the findings of a committee that “found no flaws” in greenlighting the Great Nicobar project that “will lead to the felling of a million trees” and translocating corals, reported Mongabay. The court found “no good ground to interfere”, despite “threats to a globally unique biodiversity hotspot” and Indigenous tribes at risk of displacement by the project, wrote Frontline.

- FISH FALLING: A new study found that fish biomass is “falling by 7.2% from as little as 0.1C of warming per decade”, noted the Guardian. While experts also pointed to the role of overfishing in marine life loss, marine ecologist and study lead author Dr Shahar Chaikin told the outlet: “Our research proves exactly what that biological cost [of warming] looks like underwater.”

- TOO HOT FOR COFFEE: According to new analysis by Climate Central, countries where coffee beans are grown “are becoming too hot to cultivate them”, reported the Guardian. The world’s top five coffee-growing countries faced “57 additional days of coffee-harming heat” annually because of climate change, it added.

Spotlight

Nature talks inch forward

This week, Carbon Brief covers the latest round of negotiations under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which occurred in Rome over 16-19 February.

The penultimate set of biodiversity negotiations before October’s Conference of the Parties ended in Rome last week, leaving plenty of unfinished business.

The CBD’s subsidiary body on implementation (SBI) met in the Italian capital for four days to discuss a range of issues, including biodiversity finance and reviewing progress towards the nature targets agreed under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

However, many of the major sticking points – particularly around finance – will have to wait until later this summer, leaving some observers worried about the capacity for delegates to get through a packed agenda at COP17.

The SBI, along with the subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) will both meet in Nairobi, Kenya, later this summer for a final round of talks before COP17 kicks off in Yerevan, Armenia, on 19 October.

Money talks

Finance for nature has long been a sticking point at negotiations under the CBD.

Discussions on a new fund for biodiversity derailed biodiversity talks in Cali, Colombia, in autumn 2024, requiring resumed talks a few months later.

Despite this, finance was barely on the agenda at the SBI meetings in Rome. Delegates discussed three studies on the relationship between debt sustainability and implementation of nature plans, but the more substantive talks are set to take place at the next SBI meeting in Nairobi.

Several parties “highlighted concerns with the imbalance of work” on finance between these SBI talks and the next ones, reported Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Lim Li Ching, senior researcher at Third World Network, noted that tensions around finance permeated every aspect of the talks. She told Carbon Brief:

“If you’re talking about the gender plan of action – if there’s little or no financial resources provided to actually put it into practice and implement it, then it’s [just] paper, right? Same with the reporting requirements and obligations.”

Monitoring and reporting

Closely linked to the issue of finance is the obligations of parties to report on their progress towards the goals and targets of the GBF.

Parties do so through the submission of national reports.

Several parties at the talks pointed to a lack of timely funding for driving delays in their reporting, according to ENB.

A note released by the CBD Secretariat in December said that no parties had submitted their national reports yet; by the time of the SBI meetings, only the EU had. It further noted that just 58 parties had submitted their national biodiversity plans, which were initially meant to be published by COP16, in October 2024.

Linda Krueger, director of biodiversity and infrastructure policy at the environmental not-for-profit Nature Conservancy, told Carbon Brief that despite the sparse submissions, parties are “very focused on the national report preparation”. She added:

“Everybody wants to be able to show that we’re on the path and that there still is a pathway to getting to 2030 that’s positive and largely in the right direction.”

Watch, read, listen

NET LOSS: Nigeria’s marine life is being “threatened” by “ghost gear” – nets and other fishing equipment discarded in the ocean – said Dialogue Earth.

COMEBACK CAUSALITY: A Vox long-read looked at whether Costa Rica’s “payments for ecosystem services” programme helped the country turn a corner on deforestation.

HOMEGROWN GOALS: A Straits Times podcast discussed whether import-dependent Singapore can afford to shelve its goal to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030.

‘RUSTING’ RIVERS: The Financial Times took a closer look at a “strange new force blighting the [Arctic] landscape”: rivers turning rust-orange due to global warming.

New science

- Lakes in the Congo Basin’s peatlands are releasing carbon that is thousands of years old | Nature Geoscience

- Natural non-forest ecosystems – such as grasslands and marshlands – were converted for agriculture at four times the rate of land with tree cover between 2005 and 2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Around one-quarter of global tree-cover loss over 2001-22 was driven by cropland expansion, pastures and forest plantations for commodity production | Nature Food

In the diary

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean | Brasília

- 5 March: Nepal general elections

- 9-20 March: First part of the thirty-first session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) | Kingston, Jamaica

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

Greenhouse Gases

Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’

Rising temperatures across France since the mid-1970s is putting Tour de France competitors at “high risk”, according to new research.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, uses 50 years of climate data to calculate the potential heat stress that athletes have been exposed to across a dozen different locations during the world-famous cycling race.

The researchers find that both the severity and frequency of high-heat-stress events have increased across France over recent decades.

But, despite record-setting heatwaves in France, the heat-stress threshold for safe competition has rarely been breached in any particular city on the day the Tour passed through.

(This threshold was set out by cycling’s international governing body in 2024.)

However, the researchers add it is “only a question of time” until this occurs as average temperatures in France continue to rise.

The lead author of the study tells Carbon Brief that, while the race organisers have been fortunate to avoid major heat stress on race days so far, it will be “harder and harder to be lucky” as extreme heat becomes more common.

‘Iconic’

The Tour de France is one of the world’s most storied cycling races and the oldest of Europe’s three major multi-week cycling competitions, or Grand Tours.

Riders cover around 3,500 kilometres (km) of distance and gain up to nearly 55km of altitude over 21 stages, with only two or three rest days throughout the gruelling race.

The researchers selected the Tour de France because it is the “iconic bike race. It is the bike race of bike races,” says Dr Ivana Cvijanovic, a climate scientist at the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development, who led the new work.

Heat has become a growing problem for the competition in recent years.

In 2022, Alexis Vuillermoz, a French competitor, collapsed at the finish line of the Tour’s ninth stage, leaving in an ambulance and subsequently pulling out of the race entirely.

Two years later, British cyclist Sir Mark Cavendish vomited on his bike during the first stage of the race after struggling with the 36C heat.

The Tour also makes a good case study because it is almost entirely held during the month of July and, while the route itself changes, there are many cities and stages that are repeated from year to year, Cvijanovic adds.

‘Have to be lucky’

The study focuses on the 50-year span between 1974 and 2023.

The researchers select six locations across the country that have commonly hosted the Tour, from the mountain pass of Col du Tourmalet, in the French Pyrenees, to the city of Paris – where the race finishes, along the Champs-Élysées.

These sites represent a broad range of climatic zones: Alpe d’ Huez, Bourdeaux, Col du Tourmalet, Nîmes, Paris and Toulouse.

For each location, they use meteorological reanalysis data from ERA5 and radiant temperature data from ERA5-HEAT to calculate the “wet-bulb globe temperature” (WBGT) for multiple times of day across the month of July each year.

WBGT is a heat-stress index that takes into account temperature, humidity, wind speed and direct sunlight.

Although there is “no exact scientific consensus” on the best heat-stress index to use, WBGT is “one of the rare indicators that has been originally developed based on the actual human response to heat”, Cvijanovic explains.

It is also the one that the International Cycling Union (UCI) – the world governing body for sport cycling – uses to assess risk. A WBGT of 28C or higher is classified as “high risk” by the group.

WBGT is the “gold standard” for assessing heat stress, says Dr Jessica Murfree, director of the ACCESS Research Laboratory and assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Murfree, who was not involved in the new study, adds that the researchers are “doing the right things by conducting their science in alignment with the business practices that are already happening”.

The researchers find that across the 50-year time period, WBGT has been increasing across the entire country – albeit, at different rates. In the north-west of the country, WBGT has increased at an average rate of 0.1C per decade, while in the southern and eastern parts of the country, it has increased by more than 0.5C per decade.

The maps below show the maximum July WBGT for each decade of the analysis (rows) and for hourly increments of the late afternoon (columns). Lower temperatures are shown in lighter greens and yellows, while higher temperatures are shown in darker reds and purples.

Six Tour de France locations analysed in the study are shown as triangles on the maps (clockwise from top): Paris, Alpe d’ Huez, Nîmes, Toulouse, Col du Tourmalet and Bordeaux.

The maps show that the maximum WBGT temperature in the afternoon has surpassed 28C over almost the entire country in the last decade. The notable exceptions to this are the mountainous regions of the Alps and the Pyrenees.

The researchers also find that most of the country has crossed the 28C WBGT threshold – which they describe as “dangerous heat levels” – on at least one July day over the past decade. However, by looking at the WBGT on the day the Tour passed through any of these six locations, they find that the threshold has rarely been breached during the race itself.

For example, the research notes that, since 1974, Paris has seen a WBGT of 28C five times at 3pm in July – but that these events have “so far” not coincided with the cycling race.

The study states that it is “fortunate” that the Tour has so far avoided the worst of the heat-stress.

Cvijanovic says the organisers and competitors have been “lucky” to date. She adds:

“It has worked really well for them so far. But as the frequency of these [extreme heat] events is increasing, it will be harder and harder to be lucky.”

Dr Madeleine Orr, an assistant professor of sport ecology at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that the paper was “really well done”, noting that its “methods are good [and its] approach was sound”. She adds:

“[The Tour has] had athletes complain about [the heat]. They’ve had athletes collapse – and still those aren’t the worst conditions. I think that that says a lot about what we consider safe. They’ve still been lucky to not see what unsafe looks like, despite [the heat] having already had impacts.”

Heat safety protocols

In 2024, the UCI set out its first-ever high temperature protocol – a set of guidelines for race organisers to assess athletes’ risk of heat stress.

The assessment places the potential risk into one of five categories based on the WBGT, ranging from very low to high risk.

The protocol then sets out suggested actions to take in the event of extreme heat, ranging from having athletes complete their warm-ups using ice vests and cold towels to increasing the number of support vehicles providing water and ice.

If the WBGT climbs above the 28C mark, the protocol suggests that organisers modify the start time of the stage, adapt the course to remove particularly hazardous sections – or even cancel the race entirely.

However, Orr notes that many other parts of the race, such as spectator comfort and equipment functioning, may have lower temperatures thresholds that are not accounted for in the protocol, but should also be considered.

Murfree points out that the study’s findings – and the heat protocol itself – are “really focused on adaptation, rather than mitigation”. While this is “to be expected”, she tells Carbon Brief:

“Moving to earlier start times or adjusting the route specifically to avoid these locations that score higher in heat stress doesn’t stop the heat stress. These aren’t climate preventative measures. That, I think, would be a much more difficult conversation to have in the research because of the Tour de France’s intimate relationship with fossil-fuel companies.”

The post Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Preparing for 3C

NEW ALERT: The EU’s climate advisory board urged countries to prepare for 3C of global warming, reported the Guardian. The outlet quoted Maarten van Aalst, a member of the advisory board, saying that adapting to this future is a “daunting task, but, at the same time, quite a doable task”. The board recommended the creation of “climate risk assessments and investments in protective measures”.

‘INSUFFICIENT’ ACTION: EFE Verde added that the advisory board said that the EU’s adaptation efforts were so far “insufficient, fragmented and reactive” and “belated”. Climate impacts are expected to weaken the bloc’s productivity, put pressure on public budgets and increase security risks, it added.

UNDERWATER: Meanwhile, France faced “unprecedented” flooding this week, reported Le Monde. The flooding has inundated houses, streets and fields and forced the evacuation of around 2,000 people, according to the outlet. The Guardian quoted Monique Barbut, minister for the ecological transition, saying: “People who follow climate issues have been warning us for a long time that events like this will happen more often…In fact, tomorrow has arrived.”

IEA ‘erases’ climate

MISSING PRIORITY: The US has “succeeded” in removing climate change from the main priorities of the International Energy Agency (IEA) during a “tense ministerial meeting” in Paris, reported Politico. It noted that climate change is not listed among the agency’s priorities in the “chair’s summary” released at the end of the two-day summit.

US INTERVENTION: Bloomberg said the meeting marked the first time in nine years the IEA failed to release a communique setting out a unified position on issues – opting instead for the chair’s summary. This came after US energy secretary Chris Wright gave the organisation a one-year deadline to “scrap its support of goals to reduce energy emissions to net-zero” – or risk losing the US as a member, according to Reuters.

Around the world

- ISLAND OBJECTION: The US is pressuring Vanuatu to withdraw a draft resolution supporting an International Court of Justice ruling on climate change, according to Al Jazeera.

- GREENLAND HEAT: The Associated Press reported that Greenland’s capital Nuuk had its hottest January since records began 109 years ago.

- CHINA PRIORITIES: China’s Energy Administration set out its five energy priorities for 2026-2030, including developing a renewable energy plan, said International Energy Net.

- AMAZON REPRIEVE: Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has continued to fall into early 2026, extending a downward trend, according to the latest satellite data covered by Mongabay.

- GEZANI DESTRUCTION: Reuters reported the aftermath of the Gezani cyclone, which ripped through Madagascar last week, leaving 59 dead and more than 16,000 displaced people.

20cm

The average rise in global sea levels since 1901, according to a Carbon Brief guest post on the challenges in projecting future rises.

Latest climate research

- Wildfire smoke poses negative impacts on organisms and ecosystems, such as health impacts on air-breathing animals, changes in forests’ carbon storage and coral mortality | Global Ecology and Conservation

- As climate change warms Antarctica throughout the century, the Weddell Sea could see the growth of species such as krill and fish and remain habitable for Emperor penguins | Nature Climate Change

- About 97% of South American lakes have recorded “significant warming” over the past four decades and are expected to experience rising temperatures and more frequent heatwaves | Climatic Change

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

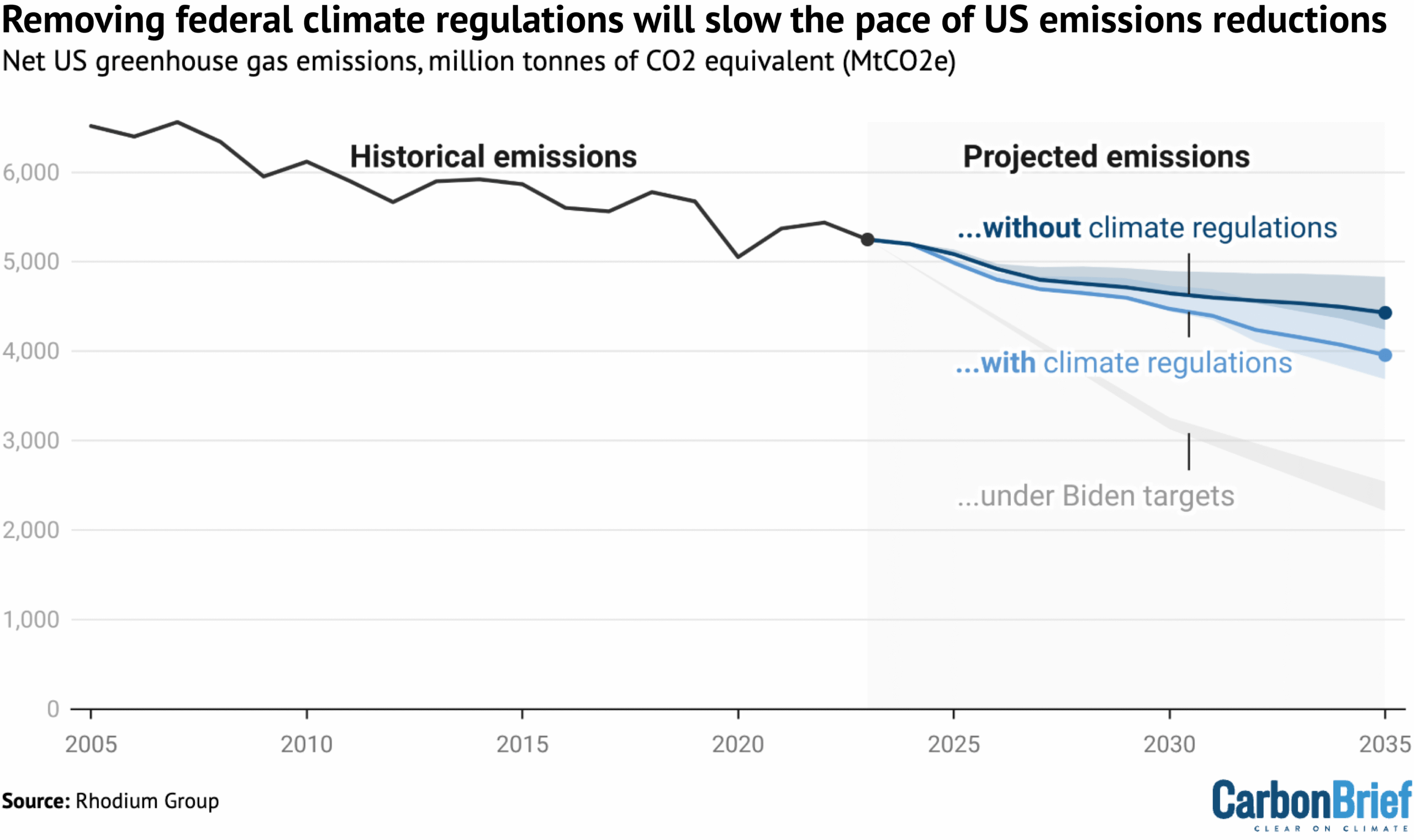

Repealing the US’s landmark “endangerment finding”, along with actions that rely on that finding, will slow the pace of US emissions cuts, according to Rhodium Group visualised by Carbon Brief. US president Donald Trump last week formally repealed the scientific finding that underpins federal regulations on greenhouse gas emissions, although the move is likely to face legal challenges. Data from the Rhodium Group, an independent research firm, shows that US emissions will drop more slowly without climate regulations. However, even with climate regulations, emissions are expected to drop much slower under Trump than under the previous Joe Biden administration, according to the analysis.

Spotlight

How a ‘tree invasion’ helped to fuel South America’s fires

This week, Carbon Brief explores how the “invasion” of non-native tree species helped to fan the flames of forest fires in Argentina and Chile earlier this year.

Since early January, Chile and Argentina have faced large-scale and deadly wildfires, including in Patagonia, which spans both countries.

These fires have been described as “some of the most significant and damaging in the region”, according to a World Weather Attribution (WWA) analysis covered by Carbon Brief.

In both countries, the fires destroyed vast areas of native forests and grasslands, displacing thousands of people. In Chile, the fires resulted in 23 deaths.

Multiple drivers contributed to the spread of the fires, including extended periods of high temperatures, low rainfall and abundant dry vegetation.

The WWA analysis concluded that human-caused climate change made these weather conditions at least three times more likely.

According to the researchers, another contributing factor was the invasion of non-native trees in the regions where the fires occurred.

The risk of non-native forests

In Argentina, the wildfires began on 6 January and persisted until the first week of February. They hit the city of Puerto Patriada and the Los Alerces and Lago Puelo national parks, in the Chubut province, as well as nearby regions.

In these areas, more than 45,000 hectares of native forests – such as Patagonian alerce tree, myrtle, coigüe and ñire – along with scrubland and grasslands, were consumed by the flames, according to the WWA study.

In Chile, forest fires occurred from 17 to 19 January in the Biobío, Ñuble and Araucanía regions.

The fires destroyed more than 40,000 hectares of forest and more than 20,000 hectares of non-native forest plantations, including eucalyptus and Monterey pine.

Dr Javier Grosfeld, a researcher at Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in northern Patagonia, told Carbon Brief that these species, introduced to Patagonia for production purposes in the late 20th century, grow quickly and are highly flammable.

Because of this, their presence played a role in helping the fires to spread more quickly and grow larger.

However, that is no reason to “demonise” them, he stressed.

Forest management

For Grosfeld, the problem in northern Patagonia, Argentina, is a significant deficit in the management of forests and forest plantations.

This management should include pruning branches from their base and controlling the spread of non-native species, he added.

A similar situation is happening in Chile, where management of pine and eucalyptus plantations is not regulated. This means there are no “firebreaks” – gaps in vegetation – in place to prevent fire spread, Dr Gabriela Azócar, a researcher at the University of Chile’s Centre for Climate and Resilience Research (CR2), told Carbon Brief.

She noted that, although Mapuche Indigenous communities in central-south Chile are knowledgeable about native species and manage their forests, their insight and participation are not recognised in the country’s fire management and prevention policies.

Grosfeld stated:

“We are seeing the transformation of the Patagonian landscape from forest to scrubland in recent years. There is a lack of preventive forestry measures, as well as prevention and evacuation plans.”

Watch, read, listen

FUTURE FURNACE: A Guardian video explored the “unbearable experience of walking in a heatwave in the future”.

THE FUN SIDE: A Channel 4 News video covered a new wave of climate comedians who are using digital platforms such as TikTok to entertain and raise awareness.

ICE SECRETS: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast explored how scientists study ice cores to understand what the climate was like in ancient times and how to use them to inform climate projections.

Coming up

- 22-27 February: Ocean Sciences Meeting, Glasgow

- 24-26 February: Methane Mitigation Europe Summit 2026, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 25-27 February: World Sustainable Development Summit 2026, New Delhi, India

Pick of the jobs

- The Climate Reality Project, digital specialist | Salary: $60,000-$61,200. Location: Washington DC

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), science officer in the IPCC Working Group I Technical Support Unit | Salary: Unknown. Location: Gif-sur-Yvette, France

- Energy Transition Partnership, programme management intern | Salary: Unknown. Location: Bangkok, Thailand

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires appeared first on Carbon Brief.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits