Developed countries have poured billions of dollars into railways across Asia, solar projects in Africa and thousands of other climate-related initiatives overseas, according to a joint investigation by Carbon Brief and the Guardian.

A group of nations, including much of Europe, the US and Japan, is obliged under the Paris Agreement to provide international “climate finance” to developing countries.

This financial support can come in forms such as grants and loans from various sources, including aid budgets, multilateral development banks (MDBs) and private investments.

The flagship climate-finance target for more than a decade was to hit “$100bn a year” by 2020, which developed countries met – albeit two years late – in 2022.

Carbon Brief and the Guardian have analysed data across more than 20,000 global climate projects funded using public money from developed nations, including official 2021 and 2022 figures, which have only just been published.

The data provides a detailed insight into how the $100bn goal was reached, including funding for everything from sustainable farming in Niger to electricity projects in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

With developed countries now pledging to ramp up climate finance further, the analysis also shows how donors often rely on loans and private finance to meet their obligations.

- The $100bn target was reached in 2022, boosted by private finance and the US

- Relatively wealthy countries – including China and the UAE – were major recipients

- A tenth of all direct climate finance went to Japan-backed rail projects

- There was funding for more than 500 clean-power projects in African countries

- Some ‘least developed’ countries relied heavily on loans

- US shares in development banks significantly inflated its total contribution

- Adaptation finance still lags, but climate-vulnerable countries received more

- Methodology

The $100bn target was reached in 2022, boosted by private finance and the US

A small handful of countries have consistently been the top climate-finance donors. This remained the case in 2021 and 2022, with just four countries – Japan, Germany, France and the US – responsible for half of all climate finance, the analysis shows.

Not only was 2022 the first year in which the $100bn goal was achieved, it also saw the largest ever single-year increase in climate finance – a rise of $26.3bn, or 29%, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

(It is worth noting that while OECD figures are often referenced as the most “official” climate-finance totals, they are contested.)

Half of this increase came from a $12.6bn rise in support from MDBs – financial institutions that are owned and funded by member states. The rest can be attributed to two main factors.

First, while several donors ramped up spending, the US drove by far the biggest increase in “bilateral” finance, provided directly by the country itself.

After years of stalling during the first Donald Trump presidency, when Joe Biden took office in 2021, the nation’s bilateral climate aid more than tripled between that year and the next.

Meanwhile, after years of “stagnating” at around $15bn, the amount of private investments “mobilised” in developing countries by developed-country spending surged to around $22bn in 2022, according to OECD estimates.

As the chart below shows, the combination of increased US contributions and higher private investments pushed climate finance up by nearly $14bn in 2022, helping it to reach $115.9bn in total.

Both of these trends are still pertinent in 2025, following a new pledge made at COP29 by developed countries to ramp up climate finance to “at least” $300bn a year by 2035.

After years of increasing rapidly under Biden, US bilateral climate finance for developing countries has been effectively eliminated during Trump’s second presidential term. Other major donors, including Germany, France and the UK, have also cut their aid budgets.

This means there will be more pressure on other sources of climate finance in the coming years. In particular, developed countries hope that private finance can help to raise finance into the trillions of dollars required to achieve developing countries’ climate goals.

Some higher-income countries – including China and the UAE – were major recipients

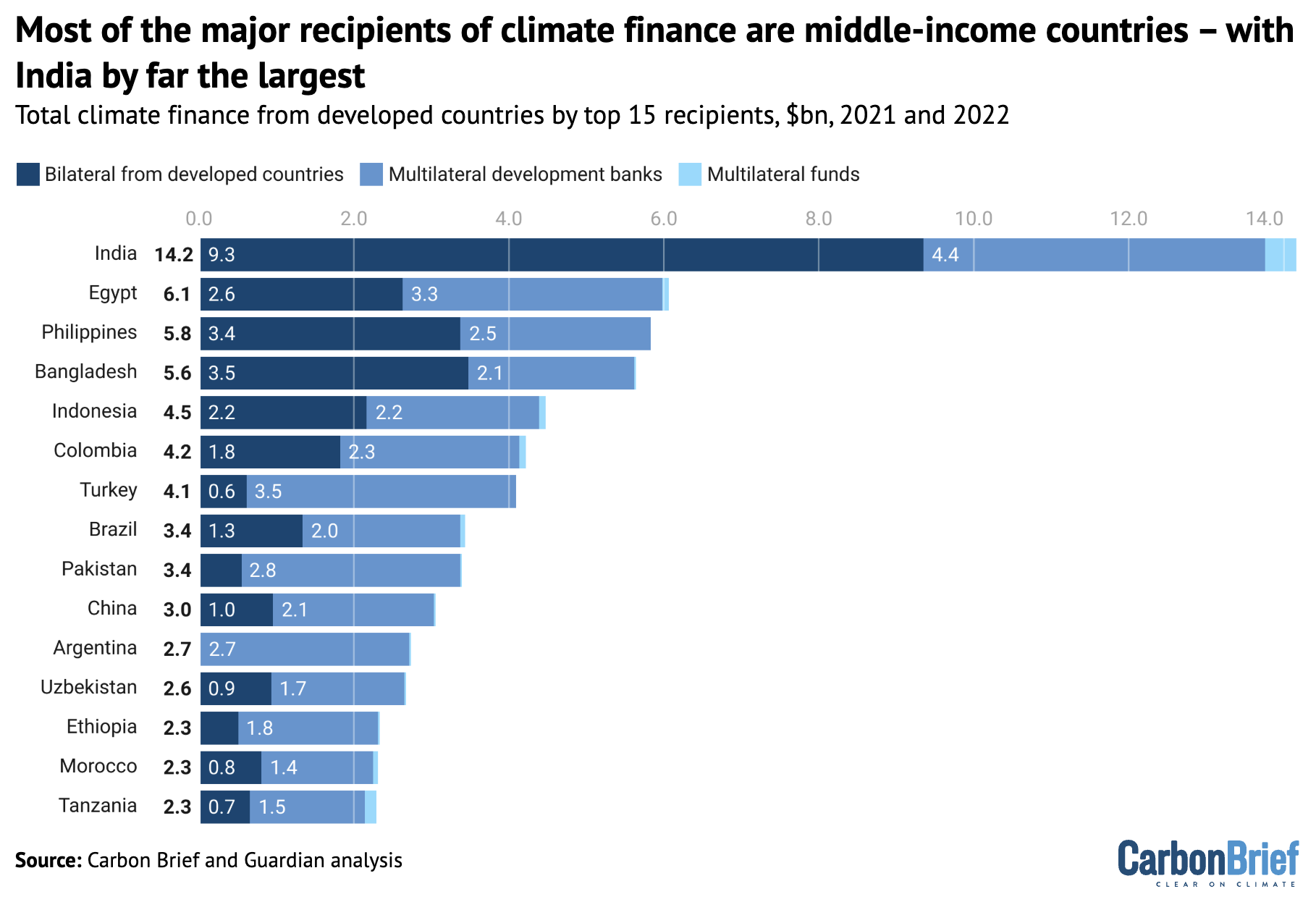

The greatest beneficiaries of international climate finance tend to be large, middle-income countries, such as Egypt, the Philippines and Brazil, according to the analysis.

(The World Bank classifies countries as being low-, lower-middle, upper-middle or high-income, according to their gross national income per person.)

Lower-middle income India received $14.1bn in 2021 and 2022 – nearly all as loans – making it by far the largest recipient, as the chart below shows.

Most of India’s top projects were metro and rail lines in cities, such as Delhi and Mumbai, which accounted for 46% of its total climate finance in those years, Carbon Brief analysis shows. (See: A tenth of all direct climate finance went to Japan-backed rail projects.)

As the world’s second-largest economy and a major funder of energy projects overseas, China – classified as upper-middle income by the World Bank – has faced mounting pressure to start officially providing climate finance. At the same time, the nation received more than $3bn of climate finance over this period, as it is still classed as a developing country under the UN climate system.

High-income Gulf petrostates are also among the countries receiving funds. For example, the UAE received Japanese finance of $1.3bn for an electricity transmission project and a waste-to-energy project.

To some extent, such large shares simply reflect the size of many middle-income countries. India received 9% of all bilateral and multilateral climate finance, but it is home to 18% of the global population.

The focus on these nations also reflects the kind of big-budget infrastructure that is being funded.

“Middle-income economies tend to have the financial and institutional capacity to design, appraise and deliver large-scale projects,” Sarah Colenbrander, climate programme director at global affairs thinktank ODI, tells Carbon Brief.

Donors might focus on relatively higher-income or powerful nations out of self-interest, for example, to align with geopolitical, trade or commercial interests. But, as Colenbrander tells Carbon Brief, there are also plenty of “high-minded” reasons to do so, not least the opportunity to help curb their relatively high emissions.

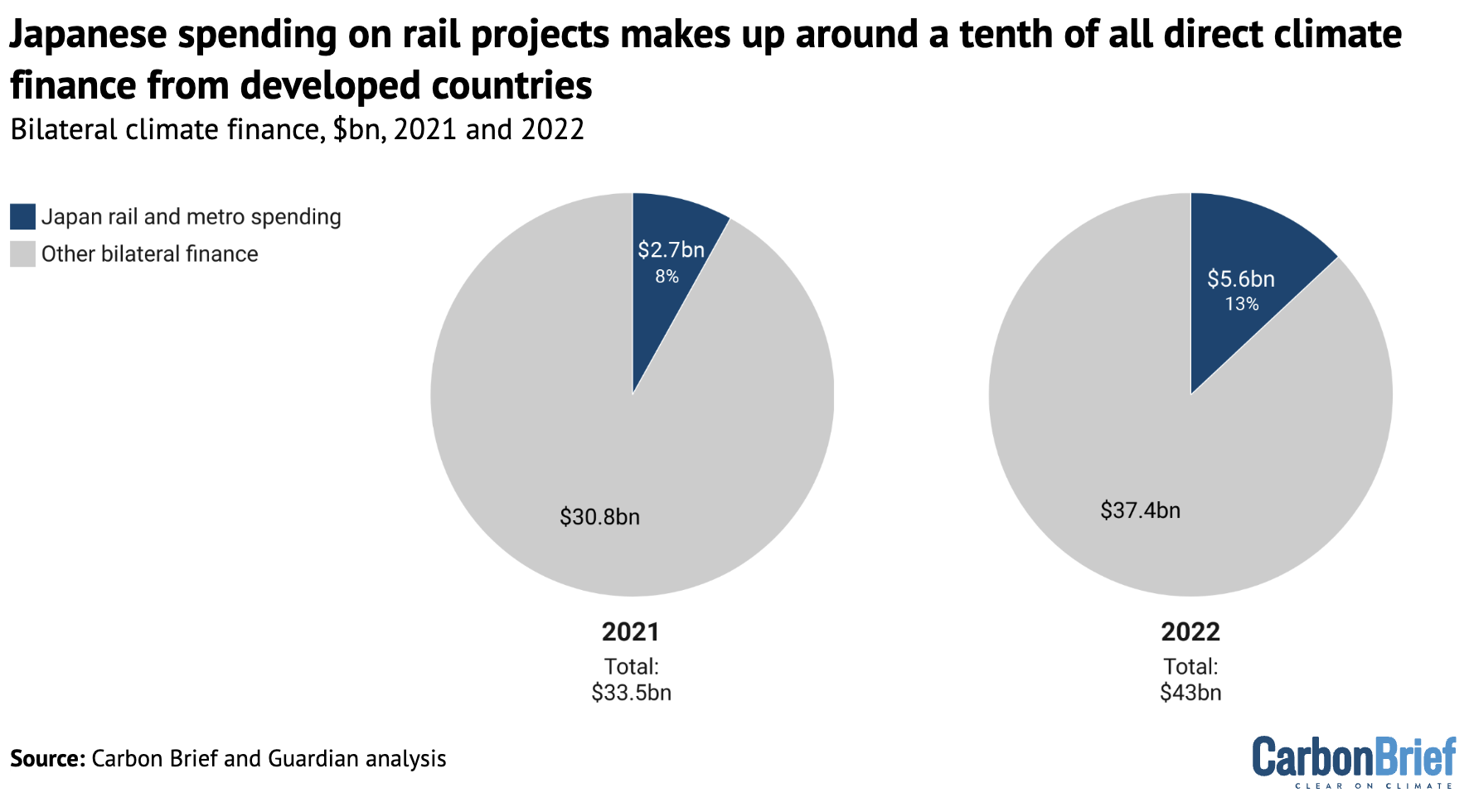

A tenth of all direct climate finance went to Japan-backed rail projects

Japan is the largest climate-finance donor, accounting for a fifth of all bilateral and multilateral finance in 2021 and 2022, the analysis shows.

Of the 20 largest bilateral projects, 13 were Japanese. These include $7.6bn of loans for eight rail and metro systems in major cities across India, Bangladesh and the Philippines.

In fact, Japan’s funding for rail projects was so substantial that it made up 11% of all bilateral finance. This amounts to 4% of climate finance from all sources.

While these rail projects are likely to provide benefits to developing countries, they also highlight some of the issues identified by aid experts with Japan’s climate-finance practices.

As was the case for more than 80% of Japan’s climate finance, all of these projects were funded with loans, which must be paid back. Nearly a fifth of Japan’s total loans were described as “non-concessional”, meaning they were offered on terms equivalent to those offered on the open market, rather than at more favourable rates.

Many Japan-backed projects also stipulate that Japanese companies and workers must be hired to work on them, reflecting the government’s policies to “proactively support” and “facilitate” the overseas expansion of Japanese business using aid.

Documents show that rail projects in India and the Philippines were granted on this basis.

This practice can be beneficial, especially in sectors such as rail infrastructure, where Japanese companies have considerable expertise. Yet, analysts have questioned Japan’s approach, which they argue can disproportionately benefit the donor itself.

“Counting these loans as climate finance presents a moral hazard…And such loans tied to Japanese businesses make it worse,” Yuri Onodera, a climate specialist at Friends of the Earth Japan, tells Carbon Brief.

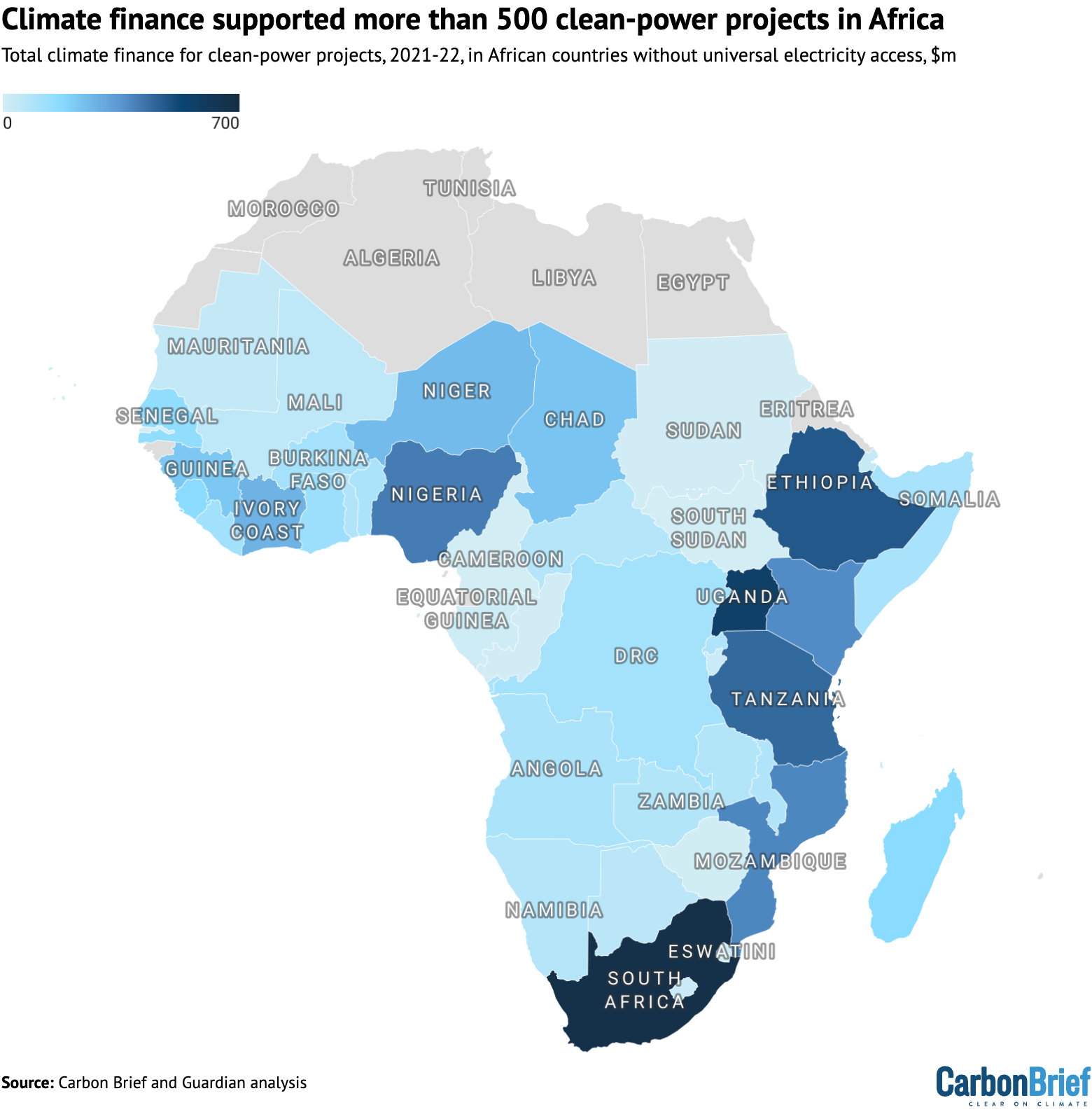

There was funding for more than 500 clean-power projects in African countries

Around 730 million people still lack access to electricity, with roughly 80% of those people living in sub-Saharan Africa.

As part of their climate-finance pledges, donor countries often support renewable projects, transmission lines and other initiatives that can provide clean power to those in need.

Carbon Brief and the Guardian have identified funding for more than 500 clean-power and transmission projects in African countries that lack universal electricity access. In total, these funds amounted to $7.6bn over the two years 2021-22.

Among them was support for Chad’s first-ever solar project, a new hydropower plant in Mozambique and the expansion of electricity grids in Nigeria.

The distribution of funds across the continent – excluding multi-country programmes – can be seen in the map below.

A lack of clear rules about what can be classified as “climate finance” in the UN climate process means donors sometimes include support for fossil fuels – particularly gas power – in their totals.

For example, Japan counted an $18m loan to a Japanese liquified natural gas (LNG) company in Senegal and roughly $1m for gas projects in Tanzania.

However, such funding accounted for a tiny fraction of sub-Saharan Africa’s climate finance overall, amounting to less than 1% of all power-sector funding across the region, based on the projects identified in this analysis.

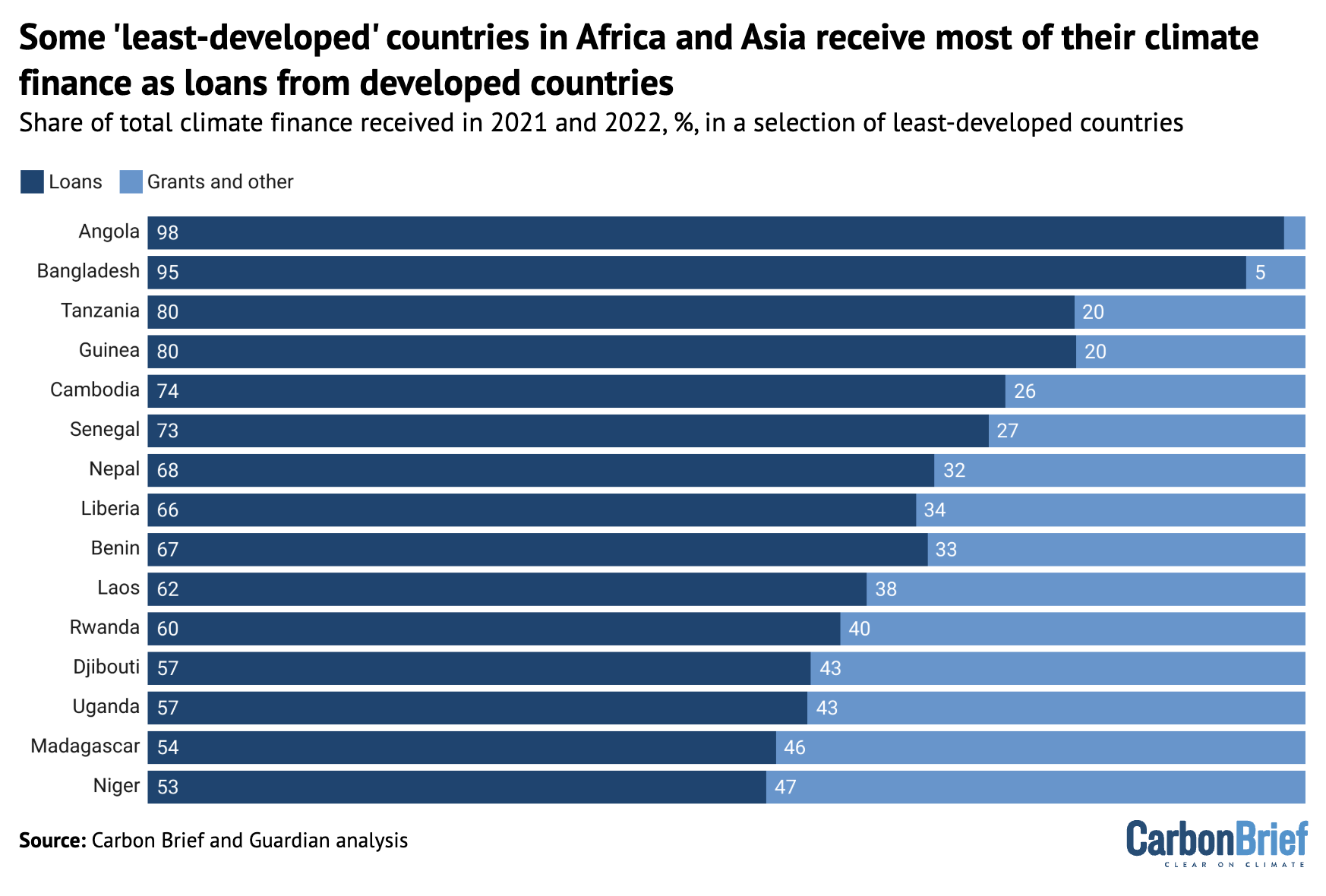

Some ‘least developed’ countries relied heavily on loans

One of the most persistent criticisms levelled at climate finance by developing-country governments and civil society groups is that so much of it is provided in the form of loans.

While loans are commonly used to fund major projects, they are sometimes offered on unfavourable terms and add to the burden of countries that are already struggling with debt.

The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) has shown that the 44 “least developed countries” (LDCs) spend twice as much servicing debts as they receive in climate finance.

Developed nations pledged $33.4bn in 2021 and 2022 to the 44 LDCs to help them finance climate projects. In total, $17.2bn – more than half of the funding – was provided as loans, primarily from Japan, France and development banks.

The chart below shows how, for a number of LDCs, loans continue to be the main way in which they receive international climate funds.

For example, Angola received $216.7m in loans from France – primarily to support its water infrastructure – and $571.6m in loans from various multilateral institutions, together amounting to nearly all the nation’s climate finance over this period.

Oxfam, which describes developed countries as “unjustly indebting poor countries” via loans, estimates that the “true value” of climate finance in 2022 was $28-35bn, roughly a quarter of the OECD’s estimate. This is largely due to Oxfam discounting much of the value of loans.

However, Jan Kowalzig, a senior policy adviser at Oxfam Germany, tells Carbon Brief that, “generally, LDCs receive loans at better conditions” than they would have been able to secure on the open market, sometimes referred to as “concessional” loans.

US shares in development banks significantly raised its total contribution

The US has been one of the world’s top climate-finance providers, accounting for around 15% of all bilateral and multilateral contributions in 2021 and 2022.

Despite this, US contributions have consistently been viewed as relatively low when considering the nation’s wealth and historical role in driving climate change.

Moreover, much of the climate finance that can be attributed to the US comes from its MDB shareholdings, rather than direct contributions from its aid budget.

These banks are owned by member countries and the US is a dominant shareholder in many of them.

The analysis reveals that around three-quarters of US climate finance provided in 2021-22 came via multilateral sources, particularly the World Bank. (For information on how this analysis attributes multilateral funding to donors, see Methodology.)

Among other major donors – specifically Japan, France and Germany – only a third of their finance was channelled through multilateral institutions. As the chart below shows, multilateral contributions lifted the US from being the fifth-largest donor to the third-largest.

While the Trump administration has cut virtually all overseas climate funding and broadly rejected multilateral institutions, the US has not yet abandoned its influential stake in MDBs.

Prior to COP29 in 2024, only MDB funds that could be attributed to developed country inputs were counted towards the $100bn goal, as part of those nations’ Paris Agreement duties.

However, countries have now agreed that “all climate-related outflows” from MDBs – no matter which donor country they are attributed to – will count towards the new $300bn goal.

This means that, as long as MDBs continue extensively funding climate projects, there will still be a large slice of climate finance that can be attributed to the US, even as it exits the Paris Agreement.

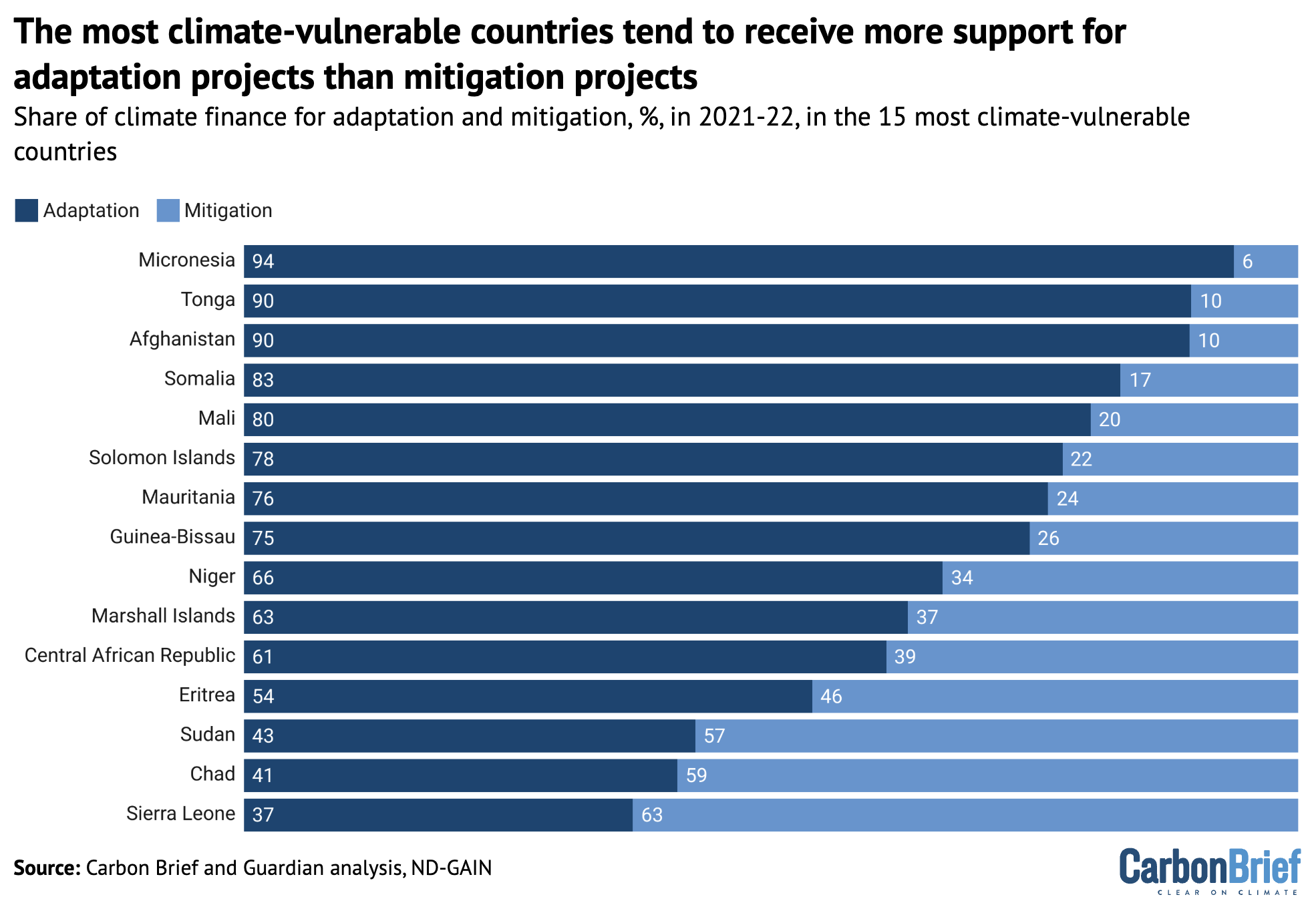

Adaptation finance still lags, but climate-vulnerable countries received more

Under the Paris Agreement, developed countries committed to achieving “a balance between adaptation and mitigation” in their climate finance.

The idea is that, while it is important to focus on mitigation – or cutting emissions – by supporting projects such as clean energy, there is also a need to help developing countries prepare for the threat of climate change.

Generally, adaptation projects are less likely to provide a return on investment and are, therefore, more reliant on grant-based finance.

In practice, a “balance” between adaptation and mitigation has never been reached. Over the period of this analysis, 58% of climate finance was for mitigation, 33% was for adaptation and the remainder was for projects that contributed to both goals.

This reflects a preference for mitigation-based financing via loans among some major donors, particularly Japan and France. Both countries provided just a third of their finance for adaptation projects in 2021 and 2022.

However, among some of the most climate-vulnerable countries – including land-locked parts of Africa and small islands – most funding was for adaptation, as the chart below shows.

Among the projects receiving climate-adaptation funds were those supporting sustainable agriculture in Niger, improving disaster resilience in Micronesia and helping those in Somalia who have been internally displaced by “climate change and food crises”.

Methodology

The joint Guardian and Carbon Brief analysis of climate finance includes the bilateral and multilateral public finance that developed countries pledged for climate projects in developing countries. It covers the years 2021 and 2022.

(These “developed” countries are the 23 “Annex II” nations, plus the EU, that are obliged to provide climate finance under the Paris Agreement.)

The analysis excludes other types of funding that contribute to the $100bn climate-finance target for climate projects, such as export credits and private finance “mobilised” by public investments. Where these have been referenced, the figures are OECD estimates. They are excluded from the analysis because export credits are a small fraction of the total, while private finance mobilised cannot be attributed to specific donor countries.

Data for bilateral funding comes from the biennial transparency reports (BTRs) each country submits to the UNFCCC. The lag in official reporting means the most recent figures – published around the end of 2024 and start of 2025 – only go up to 2022.

Many of the bilateral projects recorded by countries do not specify single recipients, but instead mention several countries. These projects have not been included when calculating the amount of finance individual developing countries received, but they are included in the total figures.

The multilateral funding, including projects funded by MDBs and multilateral climate funds, comes from the OECD. Many countries – including developing countries – pay into these institutions, which then use their money to fund climate projects and, in the case of MDBs, raise additional finance from capital markets.

This analysis calculated the shares of the “outflows” from multilateral institutions that can be attributed to developed countries. It adapts the approach used by the OECD to calculate these attributable shares for developed countries as a whole group.

As the OECD does not publish individual donor country shares that make up the total developed-country contribution, this analysis calculated each country’s attributable shares based on shareholdings in MDBs and cumulative contributions to multilateral funds. This was based on a methodology used by analysts at the World Resources Institute and ODI. There were some multilateral funds that could not be assigned using this methodology, which are therefore not captured in each country’s multilateral contribution.

The post Analysis: Seven charts showing how the $100bn climate-finance goal was met appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Seven charts showing how the $100bn climate-finance goal was met

Climate Change

A Tiny Caribbean Island Sued the Netherlands Over Climate Change, and Won

The case shows that climate change is a fundamental human rights violation—and the victory of Bonaire, a Dutch territory, could open the door for similar lawsuits globally.

From our collaborating partner Living on Earth, public radio’s environmental news magazine, an interview by Paloma Beltran with Greenpeace Netherlands campaigner Eefje de Kroon.

A Tiny Caribbean Island Sued the Netherlands Over Climate Change, and Won

Climate Change

Greenpeace organisations to appeal USD $345 million court judgment in Energy Transfer’s intimidation lawsuit

SYDNEY, Saturday 28 February 2026 — Greenpeace International and Greenpeace organisations in the US announce they will seek a new trial and, if necessary, appeal the decision with the North Dakota Supreme Court following a North Dakota District Court judgment today awarding Energy Transfer (ET) USD $345 million.

ET’s SLAPP suit remains a blatant attempt to silence free speech, erase Indigenous leadership of the Standing Rock movement, and punish solidarity with peaceful resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Greenpeace International will also continue to seek damages for ET’s bullying lawsuits under EU anti-SLAPP legislation in the Netherlands.

Mads Christensen, Greenpeace International Executive Director said: “Energy Transfer’s attempts to silence us are failing. Greenpeace International will continue to resist intimidation tactics. We will not be silenced. We will only get louder, joining our voices to those of our allies all around the world against the corporate polluters and billionaire oligarchs who prioritise profits over people and the planet.

“With hard-won freedoms under threat and the climate crisis accelerating, the stakes of this legal fight couldn’t be higher. Through appeals in the US and Greenpeace International’s groundbreaking anti-SLAPP case in the Netherlands, we are exploring every option to hold Energy Transfer accountable for multiple abusive lawsuits and show all power-hungry bullies that their attacks will only result in a stronger people-powered movement.”

The Court’s final judgment today rejects some of the jury verdict delivered in March 2025, but still awards hundreds of millions of dollars to ET without a sound basis in law. The Greenpeace defendants will continue to press their arguments that the US Constitution does not allow liability here, that ET did not present evidence to support its claims, that the Court admitted inflammatory and irrelevant evidence at trial and excluded other evidence supporting the defense, and that the jury pool in Mandan could not be impartial.[1][2]

ET’s back-to-back lawsuits against Greenpeace International and the US organisations Greenpeace USA (Greenpeace Inc.) and Greenpeace Fund are clear-cut examples of SLAPPs — lawsuits attempting to bury nonprofits and activists in legal fees, push them towards bankruptcy and ultimately silence dissent.[3] Greenpeace International, which is based in the Netherlands, is pursuing justice in Europe, with a suit against ET under Dutch law and the European Union’s new anti-SLAPP directive, a landmark test of the new legislation which could help set a powerful precedent against corporate bullying.[4]

Kate Smolski, Program Director at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, said: “This is part of a worrying trend globally: fossil fuel corporations are increasingly using litigation to attack and silence ordinary people and groups using the law to challenge their polluting operations — and we’re not immune to these tactics here in Australia.

“Rulings like this have a chilling effect on democracy and public interest litigation — we must unite against these silencing tactics as bad for Australians and bad for our democracy. Our movement is stronger than any corporate bully, and grows even stronger when under attack.”

Energy Transfer’s SLAPPs are part of a wave of abusive lawsuits filed by Big Oil companies like Shell, Total, and ENI against Greenpeace entities in recent years.[3] A couple of these cases have been successfully stopped in their tracks. This includes Greenpeace France successfully defeating TotalEnergies’ SLAPP on 28 March 2024, and Greenpeace UK and Greenpeace International forcing Shell to back down from its SLAPP on 10 December 2024.

-ENDS-

Images available in Greenpeace Media Library

Notes:

[1] The judgment entered by North Dakota District Court Judge Gion follows a jury verdict finding Greenpeace entities liable for more than US$660 million on March 19, 2025. Judge Gion subsequently threw out several items from the jury’s verdict, reducing the total damages to approximately US$345 million.

[2] Public statements from the independent Trial Monitoring Committee

[3] Energy Transfer’s first lawsuit was filed in federal court in 2017 under the RICO Act – the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a US federal statute designed to prosecute mob activity. The case was dismissed in 2019, with the judge stating the evidence fell “far short” of what was needed to establish a RICO enterprise. The federal court did not decide on Energy Transfer’s claims based on state law, so Energy Transfer promptly filed a new case in a North Dakota state court with these and other state law claims.

[4] Greenpeace International sent a Notice of Liability to Energy Transfer on 23 July 2024, informing the pipeline giant of Greenpeace International’s intention to bring an anti-SLAPP lawsuit against the company in a Dutch Court. After Energy Transfer declined to accept liability on multiple occasions (September 2024, December 2024), Greenpeace International initiated the first test of the European Union’s anti-SLAPP Directive on 11 February 2025 by filing a lawsuit in Dutch court against Energy Transfer. The case was officially registered in the docket of the Court of Amsterdam on 2 July, 2025. Greenpeace International seeks to recover all damages and costs it has suffered as a result of Energy Transfers’s back-to-back, abusive lawsuits demanding hundreds of millions of dollars from Greenpeace International and the Greenpeace organisations in the US. The next hearing in the Court of Amsterdam is scheduled for 16 April, 2026.

Media contact:

Kate O’Callaghan on 0406 231 892 or kate.ocallaghan@greenpeace.org

Climate Change

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

The Trump administration’s relentless rollback of public health and environmental protections has allowed widespread toxic exposures to flourish, warn experts who helped implement safeguards now under assault.

In a new report that outlines a dozen high-risk pollutants given new life thanks to weakened, delayed or rescinded regulations, the Environmental Protection Network, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group of hundreds of former Environmental Protection Agency staff, warns that the EPA under President Donald Trump has abandoned the agency’s core mission of protecting people and the environment from preventable toxic exposures.

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits