Developed countries have poured billions of dollars into railways across Asia, solar projects in Africa and thousands of other climate-related initiatives overseas, according to a joint investigation by Carbon Brief and the Guardian.

A group of nations, including much of Europe, the US and Japan, is obliged under the Paris Agreement to provide international “climate finance” to developing countries.

This financial support can come in forms such as grants and loans from various sources, including aid budgets, multilateral development banks (MDBs) and private investments.

The flagship climate-finance target for more than a decade was to hit “$100bn a year” by 2020, which developed countries met – albeit two years late – in 2022.

Carbon Brief and the Guardian have analysed data across more than 20,000 global climate projects funded using public money from developed nations, including official 2021 and 2022 figures, which have only just been published.

The data provides a detailed insight into how the $100bn goal was reached, including funding for everything from sustainable farming in Niger to electricity projects in the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

With developed countries now pledging to ramp up climate finance further, the analysis also shows how donors often rely on loans and private finance to meet their obligations.

- The $100bn target was reached in 2022, boosted by private finance and the US

- Relatively wealthy countries – including China and the UAE – were major recipients

- A tenth of all direct climate finance went to Japan-backed rail projects

- There was funding for more than 500 clean-power projects in African countries

- Some ‘least developed’ countries relied heavily on loans

- US shares in development banks significantly inflated its total contribution

- Adaptation finance still lags, but climate-vulnerable countries received more

- Methodology

The $100bn target was reached in 2022, boosted by private finance and the US

A small handful of countries have consistently been the top climate-finance donors. This remained the case in 2021 and 2022, with just four countries – Japan, Germany, France and the US – responsible for half of all climate finance, the analysis shows.

Not only was 2022 the first year in which the $100bn goal was achieved, it also saw the largest ever single-year increase in climate finance – a rise of $26.3bn, or 29%, according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

(It is worth noting that while OECD figures are often referenced as the most “official” climate-finance totals, they are contested.)

Half of this increase came from a $12.6bn rise in support from MDBs – financial institutions that are owned and funded by member states. The rest can be attributed to two main factors.

First, while several donors ramped up spending, the US drove by far the biggest increase in “bilateral” finance, provided directly by the country itself.

After years of stalling during the first Donald Trump presidency, when Joe Biden took office in 2021, the nation’s bilateral climate aid more than tripled between that year and the next.

Meanwhile, after years of “stagnating” at around $15bn, the amount of private investments “mobilised” in developing countries by developed-country spending surged to around $22bn in 2022, according to OECD estimates.

As the chart below shows, the combination of increased US contributions and higher private investments pushed climate finance up by nearly $14bn in 2022, helping it to reach $115.9bn in total.

Both of these trends are still pertinent in 2025, following a new pledge made at COP29 by developed countries to ramp up climate finance to “at least” $300bn a year by 2035.

After years of increasing rapidly under Biden, US bilateral climate finance for developing countries has been effectively eliminated during Trump’s second presidential term. Other major donors, including Germany, France and the UK, have also cut their aid budgets.

This means there will be more pressure on other sources of climate finance in the coming years. In particular, developed countries hope that private finance can help to raise finance into the trillions of dollars required to achieve developing countries’ climate goals.

Some higher-income countries – including China and the UAE – were major recipients

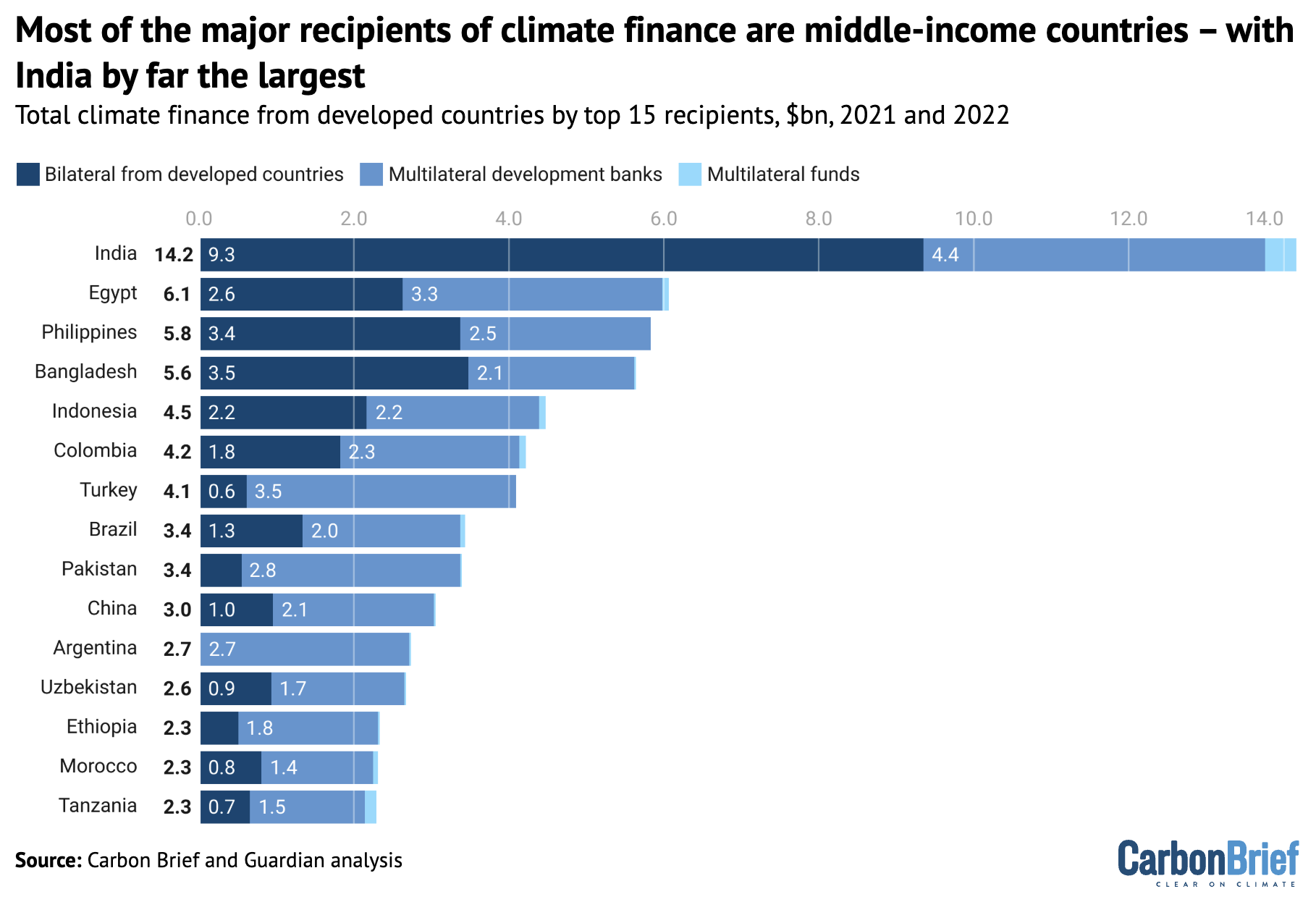

The greatest beneficiaries of international climate finance tend to be large, middle-income countries, such as Egypt, the Philippines and Brazil, according to the analysis.

(The World Bank classifies countries as being low-, lower-middle, upper-middle or high-income, according to their gross national income per person.)

Lower-middle income India received $14.1bn in 2021 and 2022 – nearly all as loans – making it by far the largest recipient, as the chart below shows.

Most of India’s top projects were metro and rail lines in cities, such as Delhi and Mumbai, which accounted for 46% of its total climate finance in those years, Carbon Brief analysis shows. (See: A tenth of all direct climate finance went to Japan-backed rail projects.)

As the world’s second-largest economy and a major funder of energy projects overseas, China – classified as upper-middle income by the World Bank – has faced mounting pressure to start officially providing climate finance. At the same time, the nation received more than $3bn of climate finance over this period, as it is still classed as a developing country under the UN climate system.

High-income Gulf petrostates are also among the countries receiving funds. For example, the UAE received Japanese finance of $1.3bn for an electricity transmission project and a waste-to-energy project.

To some extent, such large shares simply reflect the size of many middle-income countries. India received 9% of all bilateral and multilateral climate finance, but it is home to 18% of the global population.

The focus on these nations also reflects the kind of big-budget infrastructure that is being funded.

“Middle-income economies tend to have the financial and institutional capacity to design, appraise and deliver large-scale projects,” Sarah Colenbrander, climate programme director at global affairs thinktank ODI, tells Carbon Brief.

Donors might focus on relatively higher-income or powerful nations out of self-interest, for example, to align with geopolitical, trade or commercial interests. But, as Colenbrander tells Carbon Brief, there are also plenty of “high-minded” reasons to do so, not least the opportunity to help curb their relatively high emissions.

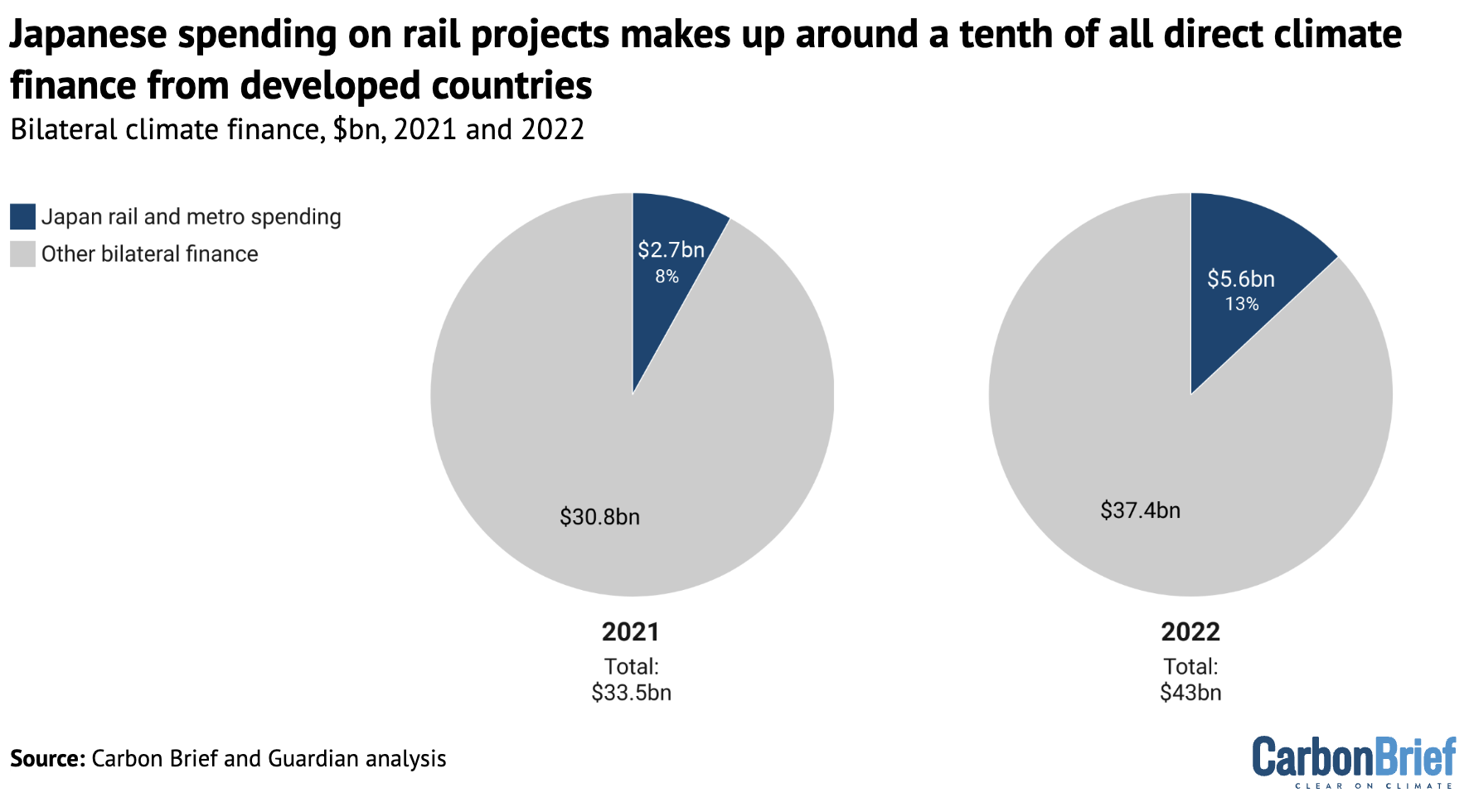

A tenth of all direct climate finance went to Japan-backed rail projects

Japan is the largest climate-finance donor, accounting for a fifth of all bilateral and multilateral finance in 2021 and 2022, the analysis shows.

Of the 20 largest bilateral projects, 13 were Japanese. These include $7.6bn of loans for eight rail and metro systems in major cities across India, Bangladesh and the Philippines.

In fact, Japan’s funding for rail projects was so substantial that it made up 11% of all bilateral finance. This amounts to 4% of climate finance from all sources.

While these rail projects are likely to provide benefits to developing countries, they also highlight some of the issues identified by aid experts with Japan’s climate-finance practices.

As was the case for more than 80% of Japan’s climate finance, all of these projects were funded with loans, which must be paid back. Nearly a fifth of Japan’s total loans were described as “non-concessional”, meaning they were offered on terms equivalent to those offered on the open market, rather than at more favourable rates.

Many Japan-backed projects also stipulate that Japanese companies and workers must be hired to work on them, reflecting the government’s policies to “proactively support” and “facilitate” the overseas expansion of Japanese business using aid.

Documents show that rail projects in India and the Philippines were granted on this basis.

This practice can be beneficial, especially in sectors such as rail infrastructure, where Japanese companies have considerable expertise. Yet, analysts have questioned Japan’s approach, which they argue can disproportionately benefit the donor itself.

“Counting these loans as climate finance presents a moral hazard…And such loans tied to Japanese businesses make it worse,” Yuri Onodera, a climate specialist at Friends of the Earth Japan, tells Carbon Brief.

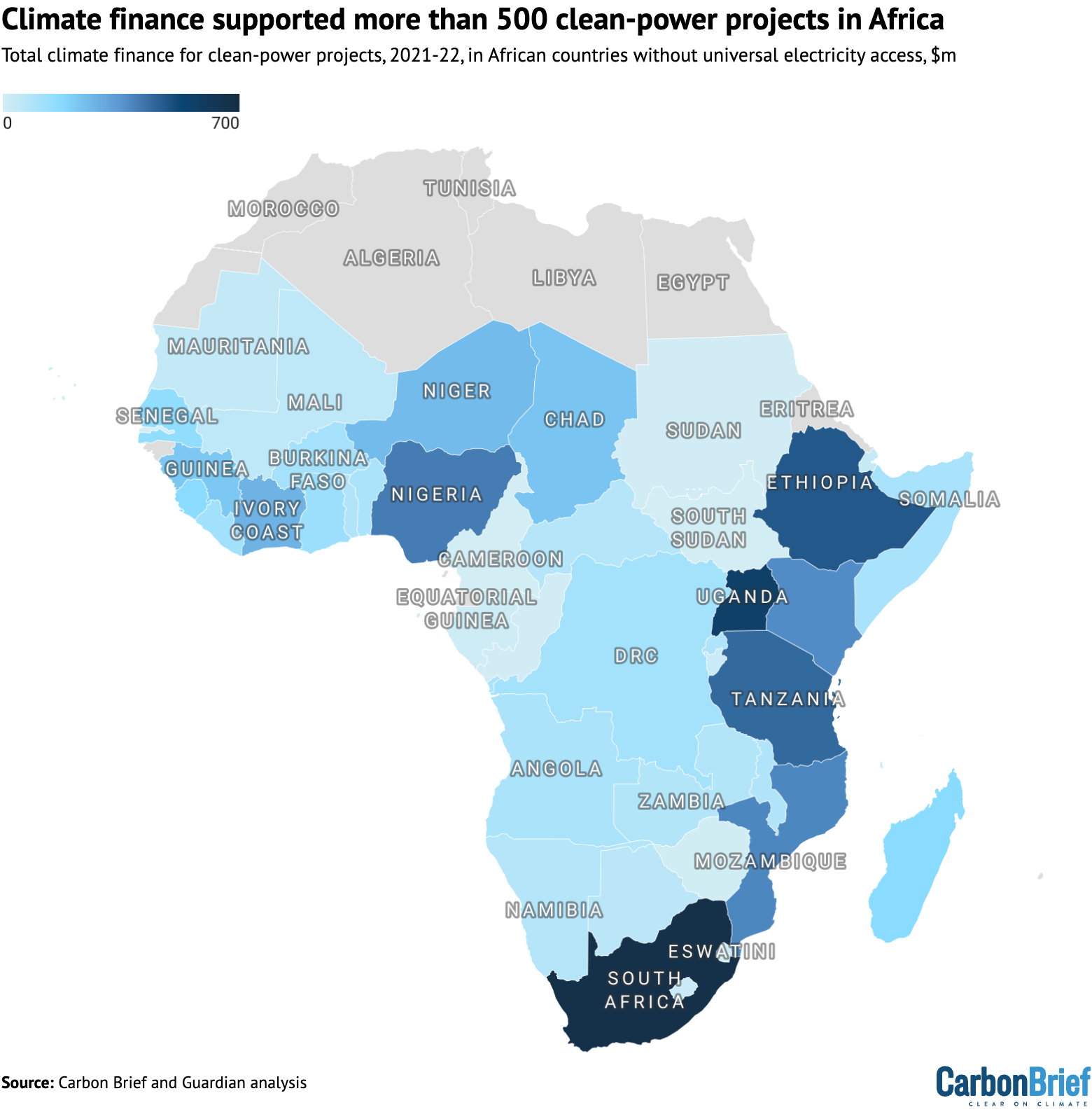

There was funding for more than 500 clean-power projects in African countries

Around 730 million people still lack access to electricity, with roughly 80% of those people living in sub-Saharan Africa.

As part of their climate-finance pledges, donor countries often support renewable projects, transmission lines and other initiatives that can provide clean power to those in need.

Carbon Brief and the Guardian have identified funding for more than 500 clean-power and transmission projects in African countries that lack universal electricity access. In total, these funds amounted to $7.6bn over the two years 2021-22.

Among them was support for Chad’s first-ever solar project, a new hydropower plant in Mozambique and the expansion of electricity grids in Nigeria.

The distribution of funds across the continent – excluding multi-country programmes – can be seen in the map below.

A lack of clear rules about what can be classified as “climate finance” in the UN climate process means donors sometimes include support for fossil fuels – particularly gas power – in their totals.

For example, Japan counted an $18m loan to a Japanese liquified natural gas (LNG) company in Senegal and roughly $1m for gas projects in Tanzania.

However, such funding accounted for a tiny fraction of sub-Saharan Africa’s climate finance overall, amounting to less than 1% of all power-sector funding across the region, based on the projects identified in this analysis.

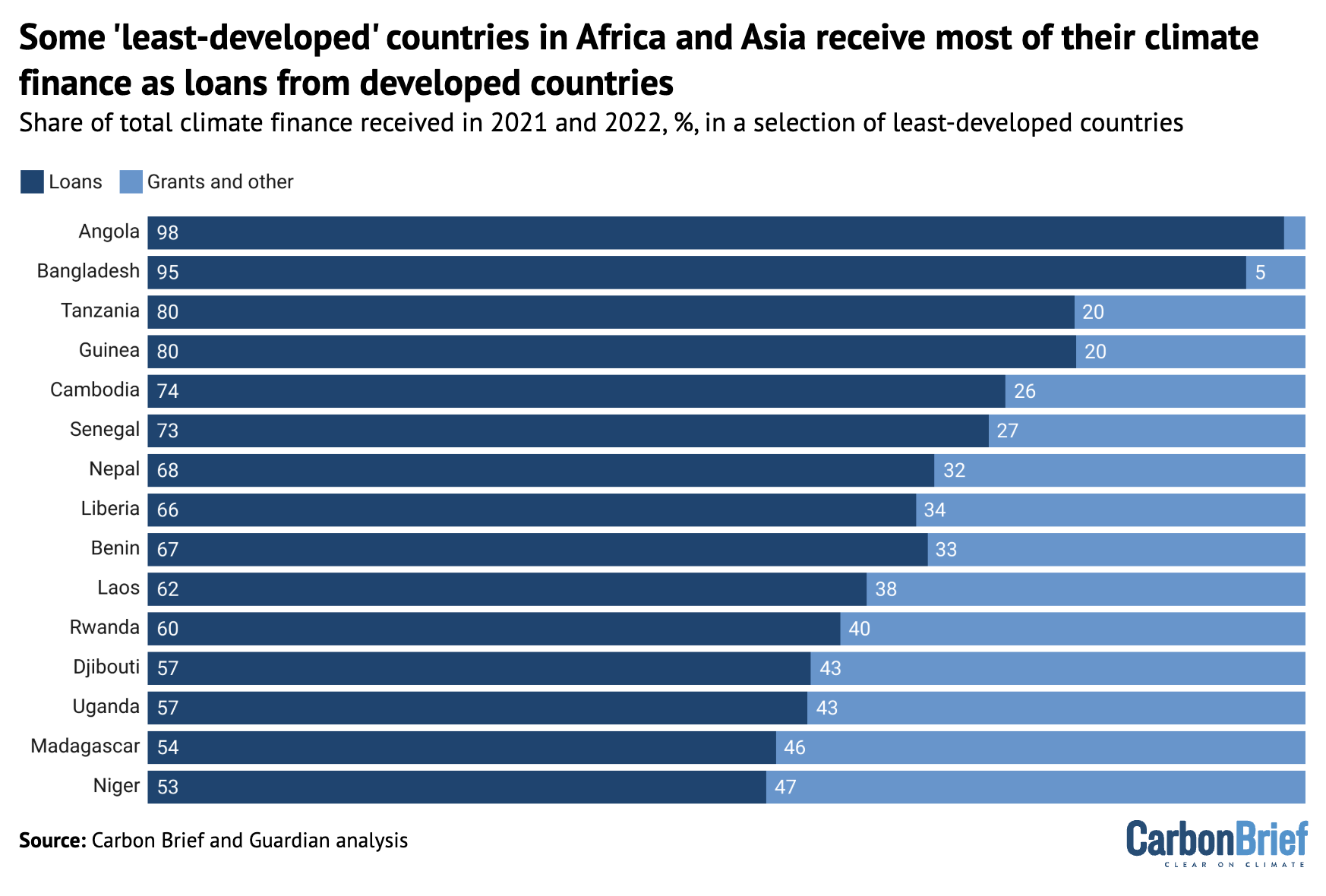

Some ‘least developed’ countries relied heavily on loans

One of the most persistent criticisms levelled at climate finance by developing-country governments and civil society groups is that so much of it is provided in the form of loans.

While loans are commonly used to fund major projects, they are sometimes offered on unfavourable terms and add to the burden of countries that are already struggling with debt.

The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) has shown that the 44 “least developed countries” (LDCs) spend twice as much servicing debts as they receive in climate finance.

Developed nations pledged $33.4bn in 2021 and 2022 to the 44 LDCs to help them finance climate projects. In total, $17.2bn – more than half of the funding – was provided as loans, primarily from Japan, France and development banks.

The chart below shows how, for a number of LDCs, loans continue to be the main way in which they receive international climate funds.

For example, Angola received $216.7m in loans from France – primarily to support its water infrastructure – and $571.6m in loans from various multilateral institutions, together amounting to nearly all the nation’s climate finance over this period.

Oxfam, which describes developed countries as “unjustly indebting poor countries” via loans, estimates that the “true value” of climate finance in 2022 was $28-35bn, roughly a quarter of the OECD’s estimate. This is largely due to Oxfam discounting much of the value of loans.

However, Jan Kowalzig, a senior policy adviser at Oxfam Germany, tells Carbon Brief that, “generally, LDCs receive loans at better conditions” than they would have been able to secure on the open market, sometimes referred to as “concessional” loans.

US shares in development banks significantly raised its total contribution

The US has been one of the world’s top climate-finance providers, accounting for around 15% of all bilateral and multilateral contributions in 2021 and 2022.

Despite this, US contributions have consistently been viewed as relatively low when considering the nation’s wealth and historical role in driving climate change.

Moreover, much of the climate finance that can be attributed to the US comes from its MDB shareholdings, rather than direct contributions from its aid budget.

These banks are owned by member countries and the US is a dominant shareholder in many of them.

The analysis reveals that around three-quarters of US climate finance provided in 2021-22 came via multilateral sources, particularly the World Bank. (For information on how this analysis attributes multilateral funding to donors, see Methodology.)

Among other major donors – specifically Japan, France and Germany – only a third of their finance was channelled through multilateral institutions. As the chart below shows, multilateral contributions lifted the US from being the fifth-largest donor to the third-largest.

While the Trump administration has cut virtually all overseas climate funding and broadly rejected multilateral institutions, the US has not yet abandoned its influential stake in MDBs.

Prior to COP29 in 2024, only MDB funds that could be attributed to developed country inputs were counted towards the $100bn goal, as part of those nations’ Paris Agreement duties.

However, countries have now agreed that “all climate-related outflows” from MDBs – no matter which donor country they are attributed to – will count towards the new $300bn goal.

This means that, as long as MDBs continue extensively funding climate projects, there will still be a large slice of climate finance that can be attributed to the US, even as it exits the Paris Agreement.

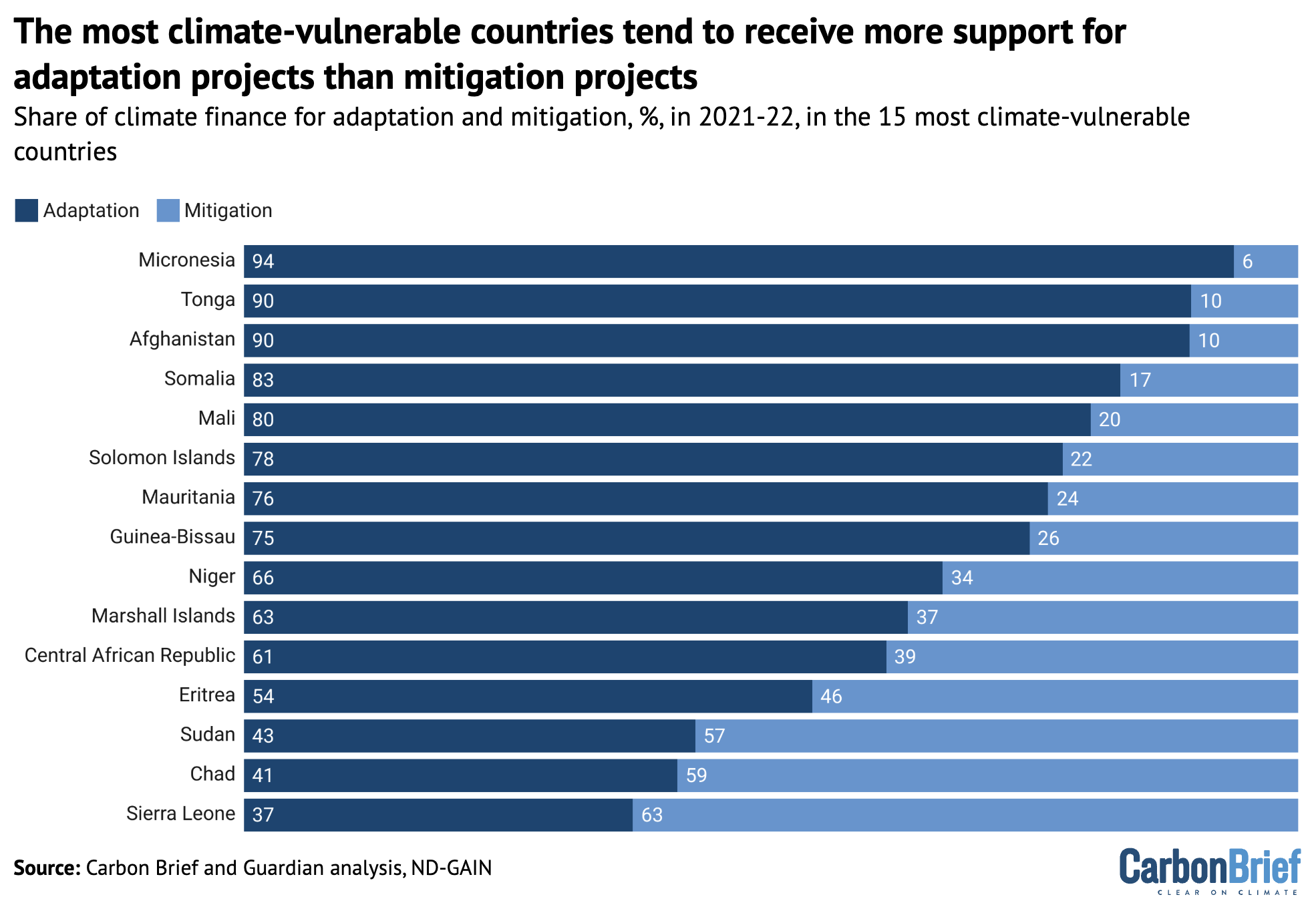

Adaptation finance still lags, but climate-vulnerable countries received more

Under the Paris Agreement, developed countries committed to achieving “a balance between adaptation and mitigation” in their climate finance.

The idea is that, while it is important to focus on mitigation – or cutting emissions – by supporting projects such as clean energy, there is also a need to help developing countries prepare for the threat of climate change.

Generally, adaptation projects are less likely to provide a return on investment and are, therefore, more reliant on grant-based finance.

In practice, a “balance” between adaptation and mitigation has never been reached. Over the period of this analysis, 58% of climate finance was for mitigation, 33% was for adaptation and the remainder was for projects that contributed to both goals.

This reflects a preference for mitigation-based financing via loans among some major donors, particularly Japan and France. Both countries provided just a third of their finance for adaptation projects in 2021 and 2022.

However, among some of the most climate-vulnerable countries – including land-locked parts of Africa and small islands – most funding was for adaptation, as the chart below shows.

Among the projects receiving climate-adaptation funds were those supporting sustainable agriculture in Niger, improving disaster resilience in Micronesia and helping those in Somalia who have been internally displaced by “climate change and food crises”.

Methodology

The joint Guardian and Carbon Brief analysis of climate finance includes the bilateral and multilateral public finance that developed countries pledged for climate projects in developing countries. It covers the years 2021 and 2022.

(These “developed” countries are the 23 “Annex II” nations, plus the EU, that are obliged to provide climate finance under the Paris Agreement.)

The analysis excludes other types of funding that contribute to the $100bn climate-finance target for climate projects, such as export credits and private finance “mobilised” by public investments. Where these have been referenced, the figures are OECD estimates. They are excluded from the analysis because export credits are a small fraction of the total, while private finance mobilised cannot be attributed to specific donor countries.

Data for bilateral funding comes from the biennial transparency reports (BTRs) each country submits to the UNFCCC. The lag in official reporting means the most recent figures – published around the end of 2024 and start of 2025 – only go up to 2022.

Many of the bilateral projects recorded by countries do not specify single recipients, but instead mention several countries. These projects have not been included when calculating the amount of finance individual developing countries received, but they are included in the total figures.

The multilateral funding, including projects funded by MDBs and multilateral climate funds, comes from the OECD. Many countries – including developing countries – pay into these institutions, which then use their money to fund climate projects and, in the case of MDBs, raise additional finance from capital markets.

This analysis calculated the shares of the “outflows” from multilateral institutions that can be attributed to developed countries. It adapts the approach used by the OECD to calculate these attributable shares for developed countries as a whole group.

As the OECD does not publish individual donor country shares that make up the total developed-country contribution, this analysis calculated each country’s attributable shares based on shareholdings in MDBs and cumulative contributions to multilateral funds. This was based on a methodology used by analysts at the World Resources Institute and ODI. There were some multilateral funds that could not be assigned using this methodology, which are therefore not captured in each country’s multilateral contribution.

The post Analysis: Seven charts showing how the $100bn climate-finance goal was met appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Seven charts showing how the $100bn climate-finance goal was met

Climate Change

China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean energy’s share of economy | Record renewables | Thawing relations with UK

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.

China Briefing handpicks and explains the most important climate and energy stories from China over the past fortnight. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Solar and wind eclipsed coal

‘FIRST TIME IN HISTORY’: China’s total power capacity reached 3,890 gigawatts (GW) in 2025, according to a National Energy Administration (NEA) data release covered by industry news outlet International Energy Net. Of this, it said, solar capacity rose 35% to 1,200GW and wind capacity was up 23% to 640GW, while thermal capacity – which is mostly coal – grew 6% to just over 1,500GW. This marks the “first time in history” that wind and solar capacity has outranked coal capacity in China’s power mix, reported the state-run newspaper China Daily. China’s grid-related energy storage capacity exceeded 213GW in 2025, said state news agency Xinhua. Meanwhile, clean-energy industries “drove more than 90%” of investment growth and more than half of GDP growth last year, said the Guardian in its coverage of new analysis for Carbon Brief. (See more in the spotlight below.)

DAWN FOR SOLAR: Solar power capacity alone may outpace coal in 2026, according to projections by the China Electricity Council (CEC), reported business news outlet 21st Century Business Herald. It added that non-fossil sources could account for 63% of the power mix this year, with coal falling to 31%. Separately, the China Renewable Energy Society said that annual wind-power additions could grow by between 600-980GW over the next five years, with annual additions of 120GW expected until 2028, said industry news outlet China Energy Net. China Energy Net also published the full CEC report.

STATE MEDIA VOICE: Xinhua published several energy- and climate-related articles in a series on the 15th five-year plan. One said that becoming a low-carbon energy “powerhouse” will support decarbonisation efforts, strengthen industrial innovation and improve China’s “global competitive edge and standing”. Another stated that coal consumption is “expected” to peak around 2027, with continued “growth” in the power and chemicals sector, while oil has already peaked. A third noted that distributed energy systems better matched the “characteristics of renewable energy” than centralised ones, but warned against “blind” expansion and insufficient supporting infrastructure. Others in the series discussed biodiversity and environmental protection and recycling of clean-energy technology. Meanwhile, the communist party-affiliated People’s Daily said that oil will continue to play a “vital role” in China, even after demand peaks.

Starmer and Xi endorsed clean-energy cooperation

CLIMATE PARTNERSHIP: UK prime minister Keir Starmer and Chinese president Xi Jinping pledged in Beijing to deepen cooperation on “green energy”, reported finance news outlet Caixin. They also agreed to establish a “China-UK high-level climate and nature partnership”, said China Daily. Xi told Starmer that the two countries should “carry out joint research and industrial transformation” in new energy and low-carbon technologies, according to Xinhua. It also cited Xi as saying China “hopes” the UK will provide a “fair” business environment for Chinese companies.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “China Briefing” email newsletter. All you need to know about the latest developments relating to China and climate change. Sent to your inbox every Thursday.

OCTOPUS OVERSEAS: During the visit, UK power-trading company Octopus Energy and Chinese energy services firm PCG Power announced they would be starting a new joint venture in China, named Bitong Energy, reported industry news outlet PV Magazine. The move “marks a notable direct entry” of a foreign company into China’s “tightly regulated electricity market”, said Caixin.

PUSH AND PULL: UK policymakers also visited Chinese clean-energy technology manufacturer Envision in Shanghai, reported finance news outlet Yicai. It quoted UK business secretary Peter Kyle emphasising that partnering with companies “like Envision” on sustainability is a “really important part of our future”, particularly in terms of job creation in the UK. Trade minister Chris Bryant told Radio Scotland Breakfast that the government will decide on Chinese wind turbine manufacturer Mingyang’s plans for a Scotland factory “soon”. Researchers at the thinktank Oxford Institute for Energy Studies wrote in a guest post for Carbon Brief that greater Chinese competition in Europe’s wind market could “help spur competition in Europe”, if localisation rules and “other guardrails” are applied.

More China news

- LIFE SUPPORT: China will update its coal capacity payment mechanism, which will raise thresholds for coal-fired power plants and expand to cover gas-fired power and pumped and new-energy storage, reported current affairs outlet China News.

- FRONTIER TECH: The world’s “largest compressed-air power storage plant” has begun operating in China, said Bloomberg.

- PARTNERSHIP A ‘MISTAKE’: The EU launched a “foreign subsidies” probe into Chinese wind turbine company Goldwind, said the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. EU climate chief Wopke Hoekstra said the bloc must resist China’s pull in clean technologies, according to Bloomberg.

- TRADE SPAT: The World Trade Organization “backed a complaint by China” that the US Inflation Reduction Act “discriminated against” Chinese cleantech exports, said Reuters.

- NEW RULES: China has set “new regulations” for the Waliguan Baseline Observatory, which provides “key scientific references for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change”, said the People’s Daily.

Captured

New or reactivated proposals for coal-fired power plants in China totalled 161GW in 2025, according to a new report covered by Carbon Brief.

Spotlight

Clean energy drove China’s economic growth in 2025

New analysis for Carbon Brief finds that clean-energy sectors contributed the equivalent of $2.1tn to China’s economy last year, making it a key driver of growth. However, headwinds in 2026 could restrict growth going forward – especially for the solar sector.

Below is an excerpt from the article, which can be read in full on Carbon Brief’s website.

Solar power, electric vehicles (EVs) and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment.

Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP)

Analysis shows that China’s clean-energy sectors nearly doubled in real value between 2022-25 and – if they were a country – would now be the 8th-largest economy in the world.

These investments in clean-energy manufacturing represent a large bet on the energy transition in China and overseas, creating an incentive for the government and enterprises to keep the boom going.

However, there is uncertainty about what will happen this year and beyond, particularly due to a new pricing system, worsening industrial “overcapacity” and trade tensions.

Outperforming the wider economy

China’s clean-energy economy continues to grow far more quickly than the wider economy, making an outsized contribution to annual growth.

Without these sectors, China’s GDP would have expanded by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%, missing the target of “around 5%” growth by a wide margin.

Clean energy made a crucial contribution during a challenging year, when promoting economic growth was the foremost aim for policymakers.

In 2024, EVs and solar had been the largest growth drivers. In 2025, it was EVs and batteries, which delivered 44% of the economic impact and more than half of the growth of the clean-energy industries.

The next largest subsector was clean-power generation, transmission and storage, which made up 40% of the contribution to GDP and 30% of the growth in 2025.

Within the electricity sector, the largest drivers were growth in investment in wind and solar power generation capacity, along with growth in power output from solar and wind, followed by the exports of solar-power equipment and materials.

But investment in solar-panel supply chains, a major growth driver in 2022-23, continued to fall for the second year, as the government made efforts to rein in overcapacity and “irrational” price competition.

Headwinds for solar

Ongoing investment of hundreds of billions of dollars represents a gigantic bet on a continuing global energy transition.

However, developments next year and beyond are unclear, particularly for solar. A new pricing system for renewable power is creating uncertainty, while central government targets have been set far below current rates of clean-electricity additions.

Investment in solar-power generation and solar manufacturing declined in the second half of the year.

The reduction in the prices of clean-energy technology has been so dramatic that when the prices for GDP statistics are updated, the sectors’ contribution to real GDP – adjusted for inflation or, in this case deflation – will be revised down.

Nevertheless, the key economic role of the industry creates a strong motivation to keep the clean-energy boom going. A slowdown in the domestic market could also undermine efforts to stem overcapacity and inflame trade tensions by increasing pressure on exports to absorb supply.

Local governments and state-owned enterprises will also influence the outlook for the sector.

Provincial governments have a lot of leeway in implementing the new electricity markets and contracting systems for renewable power generation. The new five-year plans, to be published this year, will, therefore, be of major importance.

This spotlight was written for Carbon Brief by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), and Belinda Schaepe, China policy analyst at CREA. CREA China analysts Qi Qin and Chengcheng Qiu contributed research.

Watch, read, listen

PROVINCE INFLUENCE: The Institute for Global Decarbonization Progress, a Beijing-based thinktank, published a report examining the climate-related statements in provincial recommendations for the 15th five-year plan.

‘PIVOT’?: The Outrage + Optimism podcast spoke with the University of Bath’s Dr Yixian Sun about whether China sees itself as a climate leader and what its role in climate negotiations could be going forward.

COOKING FOR CLEAN-TECH: Caixin covered rising demand for China’s “gutter oil” as companies “scramble” to decarbonise.

DON’T GO IT ALONE: China News broadcast the Chinese foreign ministry’s response to the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement, with spokeswoman Mao Ning saying “no country can remain unaffected” by climate change.

$6.8tn

The current size of China’s green-finance economy, including loans, bonds and equity, according to Dr Ma Jun, the Institute of Finance and Sustainability’s president,in a report launch event attended by Carbon Brief. Dr Ma added that “green loans” make up 16% of all loans in China, with some areas seeing them take a 34% share.

New science

- China’s official emissions inventories have overestimated its hydrofluorocarbon emissions by an average of 117m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (mtCO2e) every year since 2017 | Nature Geoscience

- “Intensified forest management efforts” in China from 2010 onwards have been linked to an acceleration in carbon absorption by plants and soils | Communications Earth and Environment

Recently published on WeChat

China Briefing is written by Anika Patel and edited by Simon Evans. Please send tips and feedback to china@carbonbrief.org

The post China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean energy’s share of economy | Record renewables | Thawing relations with UK appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Congress rescues aid budget from Trump’s “evisceration” but climate misses out

Under pressure from Congress, President Donald Trump quietly signed into law a funding package that provides billions of dollars more in foreign assistance spending than he had originally wanted to for the fiscal year between October 2025 and September 2026.

The legislation allocates $50 billion, $9 billion less than the level agreed the previous year under President Biden but $19 billion more than Trump proposed, restoring health and humanitarian aid spending to near pre-Trump levels.

Democratic Senator Patty Murray, vice-chair of the committee on appropriations, said that “while including some programmatic funding cuts, the bill rejects the Trump administration’s evisceration of US foreign assistance programmes”.

But, with climate a divisive issue in the US, spending on dedicated climate programmes was largely absent. Clarence Edwards, executive director of E3G’s US office, told Climate Home News that “the era of large US government investment in climate policy is over, at least for the foreseeable future”.

The package ruled out any support for the Climate Investment Funds’ Clean Technology Fund, which supports low-carbon technologies in developing countries and had received $150 million from the US in the previous fiscal year.

The US also made no pledge to the Africa Development Fund (ADF) – a mechanism run by the African Development Bank that provides grants and low-interest loans to the poorest African nations. A government spokesperson told Reuters that decision reflected concerns that “like too many other institutions, the ADF has adopted a disproportionate focus on climate change, gender, and social issues”.

GEF spared from cuts

Trump did, however, agree to Congress’s request to make $150 million – more than last year – available for the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which tackles environmental issues like biodiversity loss, land degradation and climate change.

Edwards said that GEF funding “survived due to Congressional pushback and a refocus on non-climate priorities like biodiversity, plastics and ocean ecosystems, per US Treasury guidance”.

Congress also pressured Trump into giving $54 million to the Rome-based International Fund for Agricultural Development. Its goals include helping small-scale farmers adapt to climate change and reduce emissions.

Without any pressure from Congress, Trump approved tens of millions of dollars each for multilateral development banks in Asia, Africa and Europe and just over a billion dollars for the World Bank’s International Development Association, which funds development projects in the world’s poorest countries.

As most of these banks have climate programmes and goals, much of this money is likely to be spent on climate action. The largest lender, the World Bank, aims to devote 45% of its finance to climate programmes, although, as Climate Home News has reported, its definition of climate spending is considered too loose by some analysts.

The bill also earmarks $830 million – nearly triple what Trump originally wanted – for the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a George W. Bush-era institution that has increasingly backed climate-focussed projects like transmission lines to bring clean hydropower to cities in Nepal.

No funding boost for DFC

While Congress largely increased spending, it rejected Trump’s call for nearly $4 billion for the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), granting just under $1 billion instead – similar to previous years.

Under Biden, there had been a push to get the DFC to support clean energy projects. But the Trump administration ended DFC’s support for projects like South Africa’s clean energy transition.

At a recent board meeting, the DFC’s board – now dominated by Trump administration officials – approved US financial support for Chevron Mediterranean Limited, the developers of an Israeli gas field.

Kate DeAngelis, deputy director at Friends of the Earth US told Climate Home News it was good for the climate that Trump had not been able to boost the DFC’s budget. “DFC seems set up to focus mainly on the dirtiest deals without any focus on development,” she said.

US Congressional elections in November could lead to Democrats retaking control of one or both houses of Congress. Edwards said that “Democratic gains might restore funding [in the next fiscal year], while Republican holds would likely extend cuts”.

But he warned that “budgetary pressures and a murky economic environment don’t hold promise of increases in US funding for foreign assistance and climate programs, regardless of which party controls Congress”.

The post Congress rescues aid budget from Trump’s “evisceration” but climate misses out appeared first on Climate Home News.

Congress rescues aid budget from Trump’s “evisceration” but climate misses out

Climate Change

Green groups sue EU over inclusion of Portuguese lithium mine on priority list

Environmental campaigners and community groups are suing the European Commission over its decision to designate a controversial lithium mine in Portugal as “strategic” to secure the minerals it needs for the energy transition.

They argue that the Barroso mine, intended to supply lithium to the EV battery industry, poses serious environmental, social and safety risks and that the EU’s executive arm failed to properly assess the project’s sustainability. They filed the case at the European Court of Justice on Thursday.

A spokesperson for the EU Commission said it could not comment on the case as legal proceedings have now started.

The mine is one of 47 mineral projects, which the Commission labelled as “strategic“ to shore up the bloc’s reserves of energy transition minerals, granting them preferential treatment for gaining permits and easier access to EU funding.

London-listed Savannah Resources is planning to dig four open pit mines in the northern Barroso region to extract lithium from Europe’s largest known deposit. The company says it will extract enough lithium every year to produce around half a million batteries for electric vehicles.

However, local groups have staunchly opposed the mining project, citing concerns over waste management and water use as well as the impact of the mine on traditional agriculture in the area.

Savannah Resources did not respond to a request for comment at the time of publication.

EU Commission rejected NGOs’ concerns

The lawsuit comes weeks after the Commission rejected requests by green groups to review the status of 16 controversial projects on its strategic list, including the Barroso mine, despite environmental concerns expressed by NGOs and local communities. The Commission found their concerns to be “unfounded” and argued that member states were responsible for ensuring that the projects comply with EU environmental laws.

Environmental NGO ClientEarth and the United Association for the Defense of Covas do Barroso (UDCB), which filed the case, argue that the Commission overlooked gaps in the assessment of the mine’s environmental impacts, including risks to protected species and the safety of a planned facility to store mining waste.

They are asking the court to quash the Commission’s decision to keep the project on its strategic list and to clarify its obligations to ensure that projects on the list follow sustainable mining practices.

“We are going to court because the Commission’s decision undermines fundamental EU legal principles,” they said in a statement.

“Labelling a project ‘strategic’ and in the public interest while turning a blind eye to well-documented risks to water, ecosystems, human health and local livelihoods is simply unacceptable. The energy transition must be based on law, science and justice – not political shortcuts that turn rural regions into sacrifice zones,” they added.

EU seeks to shore up access to minerals

Under the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act, the Commission identified a host of mining projects that could boost the bloc’s access to the minerals it needs to manufacture clean energy and other advanced technologies, as well as reduce its dependence on supplies from China.

The law allows the Commission to designate mineral projects as strategic if they meet a series of criteria, including that the project “would be implemented sustainably” and monitor, prevent and minimise environmental and adverse social impacts.

The status does not constitute an approval for the project and developers still need to obtain the necessary permits from the relevant national or regional authorities.

Earlier this week, the European Court of Auditors found that many projects designated as strategic remain at an early stage of development and will struggle to meaningfully contribute to securing mineral supplies for the EU by 2030.

The post Green groups sue EU over inclusion of Portuguese lithium mine on priority list appeared first on Climate Home News.

Green groups sue EU over inclusion of Portuguese lithium mine on priority list

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility