A Conservative victory over the Liberals in the Canadian election could lead to nearly 800m extra tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions over the next decade, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

This amounts to the entire annual emissions of the UK and France combined.

These extra emissions would cause around C$233bn ($169bn) in climate damages around the world, based on the Canadian government’s official costings.

The right-leaning Conservative party, led by Pierre Poilievre, has pledged to cut one of the nation’s most significant climate policies – industrial carbon pricing – as well as other key regulations.

If these policies are removed and not replaced, modelling by researchers from Simon Fraser University and University of Victoria shows that Canada’s gradually declining emissions would likely start to creep up again in the coming years.

In contrast, emissions would continue to fall under the policies currently backed by Mark Carney’s centrist Liberal party, which has overseen a modest decrease over the past decade.

However, Carbon Brief analysis of the modelling also suggests that neither of the major parties’ policy platforms would put Canada on track to reach any of its climate targets.

These figures complement analysis by the Canadian government showing that the nation still needs to implement more ambitious measures in order to reach its target to cut emissions to net-zero by 2050.

(For more on Canada’s election, see Carbon Brief’s manifesto tracker, which captures what the major parties have said about climate change, energy and nature.)

Conservatives could raise emissions

Canada is the world’s 10th biggest emitter of greenhouse gases. Significant contributors include its sizeable oil-and-gas sector and high emissions from transport.

The nation has been relatively slow to decarbonise. However, after a decade of rule by the Liberals, led by prime minister Justin Trudeau, there has been a small dip in Canada’s emissions.

With a federal election looming, an unpopular Trudeau resigned and was replaced in March by Carney, an economist with a background in climate finance.

His main rival in the election, which takes place on 28 April, will be the Conservatives, a party that until recently was the clear favourite. Conservative leader Poilievre has accused the Liberal government of pursuing “net-zero environmental extremism” and Carney of being part of the “radical net-zero movement”.

A sudden shift in polling that put the Liberals ahead has been widely attributed to their right-leaning opponents’ alignment with Donald Trump. This alignment has become politically toxic, following the US president’s tariffs and talk of annexing Canada.

Carbon pricing is at the heart of Canadian climate politics. Poilievre has long pledged to “axe the tax”, referring to a consumer levy that is meant to incentivise people to use less fossil fuel.

When Carney took office, his first action was to cut this carbon tax to zero, effectively ending his party’s signature climate policy.

In response, Poilievre pledged to cut the “entire carbon tax”, referring to a federal backstop on carbon pricing applied to major industrial emitters, such as fossil-fuel producers. He has also committed to abandoning other climate regulations.

The impact of these rollbacks is illustrated by the “Conservatives” line in the figure below, based on the party’s climate-related announcements to date. Notably, Canada’s emissions would be expected to start rising again, reversing some of the recent decline.

The “Liberals” line is based on current federal policies, excluding the consumer carbon tax. It would see a continued, steady drop in emissions if the Liberals retain power, even if they fail to implement any new climate policies after the election.

As such, a Conservative victory could mean an additional 771m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) entering the atmosphere by 2035.

Along with the US, Canada has long calculated the “social cost of carbon” and other greenhouse gases, in order to place a value on any emissions changes resulting from new regulations.

Based on Carbon Brief analysis of the government’s own figures for this metric, the extra emissions released under a Conservative government could result in global damages worth C$233bn ($169bn).

The emissions trajectories out to 2035 are based on modelling carried out by climate scientists Emma Starke, a PhD researcher at Simon Fraser University, and Dr Katya Rhodes, an associate professor at the University of Victoria.

Starke and Rhodes simulated the policy platforms of the two major Canadian parties using the CIMS energy-economy model, a well-established tool for understanding the country’s federal climate policies.

The researchers ran the models out to 2035, twice the normal parliamentary term length, to reflect the timespan it can take for policies to significantly affect annual emissions.

Starke tells Carbon Brief the “simple message” of their work is that a federal Liberal government is “likely to continue reducing emissions while a Conservative government would see them rise significantly”.

If the Conservative party were to trigger such a reversal, Canada would be the only G7 nation with rising emissions.

The nation is already something of an outlier, with slower emissions cuts than most major global-north economies and per-capita emissions three times higher than the EU average.

Even in the “Liberals” scenario modelled by Starke and Rhodes, emissions would only fall to 1990 levels in 2035. Meanwhile, nations such as the UK and Germany have already roughly halved their emissions from 1990 levels, even as their economies have expanded.

Canada continues to miss targets

Canada has a net-zero target for 2050. Under the Canadian Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act, it also has interim targets of cutting its emissions to 20% below 2005 levels by 2026, 40-45% by 2030 and 45-50% by 2035.

As the yellow lines in the chart above show, neither of the major Canadian parties has set out a policy programme that is sufficient to achieve the nation’s climate targets.

Emissions cuts from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF), which count towards these targets, are not captured in the CIMS modelling of the two parties’ climate policies.

However, even when accounting for projected LULUCF emissions reductions, Carbon Brief analysis suggests a potential Liberal government’s annual emissions could be nearly one-third higher than the 2030 target.

Under a Conservative government, this gap could widen to more than 50% higher. (For more information about LULUCF estimates, see the Methodology.)

For context, the Conservatives’ gap in 2030 would be nearly equivalent to the entire annual emissions of Bangladesh. The Liberals’ gap in the same year would be roughly the size of Kuwait’s annual emissions.

This pessimistic outlook is supported by analysis from the Canadian government itself and independent analysts at the Canadian Climate Institute (CCI). Both have repeatedly shown that Canada is not on track to achieve its climate targets. (Analysts at Climate Action Tracker have also described Canada’s policies as “insufficient” to reach the world’’s Paris Agreement targets.)

This is confirmed by the most recent official projections, published by the government in December 2024 alongside Canada’s first “biennial transparency report” (BTR) to the UN.

The chart below shows that neither of the main scenarios modelled by the government would be sufficient for Canada to reach its targets, meaning further policies would be needed to get on track.

Even in the government’s most optimistic scenario, Canada would only achieve an 18% emissions cut by 2026 – rather than the 20% being targeted – and a 34% cut by 2030, rather than 40%.

The “reference” scenario, shown by the upper grey line in the chart above, accounts for all federal, provincial and territorial policies that were in place by August 2024 and assumes no further government action. (This means it does not include more recent actions, such as scrapping consumer carbon pricing.)

The “additional measures” scenario, shown by the lower grey line in the chart above, includes extra measures that were announced, but not yet implemented.

It also includes extra emissions cuts from nature-based solutions, agricultural changes and a small number of international carbon credits purchased from the Western Climate Initiative. (Both scenarios also include accounting contributions from LULUCF.)

As the chart shows, the “Liberals” scenario modelled by Starke and Rhodes broadly aligns with the reference scenario, once LULUCF contributions are included. (This is despite Starke and Rhodes excluding the consumer carbon tax, see below.)

In the introduction to Canada’s 2024 BTR, Liberal climate minister Steven Guilbeault writes:

“We have more work to do to achieve our enhanced 2030 target of 40-45% below 2005 emissions.”

The parties’ climate platforms

In an election dominated by the growing economic threat from the US, climate change has not been seen as a key issue by either politicians or voters. (See Carbon Brief’s election manifesto tracker for more on how climate has featured so far.)

The modelling by Starke and Rhodes captures the impact of the climate policy proposals that have been announced by the Liberals and the Conservatives ahead of election day.

These mainly consist of Conservative commitments to eliminate parts of Canada’s climate strategy, citing high costs. Perhaps most significantly, the party has pledged to scrap industrial carbon pricing.

This policy involves setting limits on emissions from high-polluting businesses such as steel and fossil-fuel companies. Industries pay for emissions above a certain limit and can obtain saleable credits if they reduce their emissions below that limit.

Provinces and territories can set up their own pricing systems, but there is a federal backstop representing the minimum standards that are required.

Oil-producing regions have already moved to abandon industrial carbon pricing, challenging the federal government to enforce the backstop.

Canada’s climate policies overlap and complement each other in various ways, making it difficult to assign shares of emissions cuts to specific policies.

However, the CCI calculated in 2024 that industrial carbon pricing was set to be the “single biggest driver of emissions reductions” by 2030, accounting for 20-48% of emissions cuts expected over the next five years.

Consumer carbon pricing, commonly referred to simply as the “carbon tax”, is paid by households and small businesses on fuels such as petrol and gas. The CCI estimates that it would only have been responsible for 8-14% of emissions cuts by 2030.

Both parties have abandoned consumer carbon pricing and this is captured in the emissions trajectories modelled by Starke and Rhodes.

The Conservative election manifesto confirms earlier pledges to scrap a list of climate policies, which are also captured in the modelling. These include Canada’s electric vehicle sales mandate, clean-fuel regulations and clean-electricity regulations.

The electric-vehicle targets, part of Canada’s objective to phase out petrol and diesel vehicle sales by 2035, have been dismissed by Poilievre as a “tax on the poor” that result in people being “forced to pay” extra for electric cars.

Poilievre has referred to clean-fuel regulations, which are intended to boost hydrogen and other alternative fuels in the transport sector, as another form of “carbon tax”. Government estimates suggest these measures would cut emissions by 26MtCO2s annually by 2030.

Unlike these transport-related measures, the clean-electricity regulations are not set to kick in until 2035, so they make minimal difference to the two parties’ trajectories.

The Conservatives have also pledged to scrap the planned emissions cap on Canada’s oil-and-gas sector. The modellers left this out of their simulations, as it has yet to be legislated and there are still uncertainties about its implementation.

The modelling assumes that the Conservatives remove these climate policies and then do not replace them with anything else.

This may not be how things would play out. While the Conservatives are traditionally more opposed to climate action than the Liberals, they have not confirmed that they would withdraw from their national or international obligations altogether.

Indeed, Poilievre has described “technology, not taxes” as “the best way to fight climate change”, saying clean industries should be encouraged in Canada by expanding tax credits. Such proposals are not captured in this modelling.

Starke and Rhodes write that these would in any case have limited impact:

“We do not analyse the effect of various subsidies such as tax credits and grants because all political parties promise these and they have only a marginal effect on greenhouse gas emissions.”

There is also uncertainty around the impact an escalating trade war might have in Canada – including its fossil-fuel sector – as politicians seek to bolster domestic industries. This makes it harder to predict future emissions trajectories under the two parties.

The Conservatives have been more vocal about backing Canada’s fossil-fuel industry, but the Liberals have also expressed support for the sector, including pipeline projects. However, the lack of clarity on such measures mean they only have a “modest effect” in the CIMS modelling, according to Starke and Rhodes.

Methodology

The “Liberal” and “Conservative” scenarios in this article come from modelling by Emma Starke, a PhD researcher at Simon Fraser University, and Dr Katya Rhodes, an associate professor at the University of Victoria.

They used the CIMS energy-economy model to simulate the impact of removing key climate policies, in cases where parties have been clear about their intention to do so.

They did not account for policies that were deemed to have “only a marginal effect on greenhouse gas emissions” and focused on “key regulatory and pricing policies because these are the most important for reducing greenhouse gas emissions”. Their approach is outlined in an article for Policy Options.

The analysis uses the “medium growth scenario” from Statistics Canada forecasts of population and GDP growth.

In the first chart, Carbon Brief uses historical emissions data from Canada’s official greenhouse gas inventory, which at the time of publication includes figures up to 2023. Note that Canadian historical emissions data has undergone changes between years as the government has shifted its methodology. This results in differences between datasets.

Canada’s emissions targets use the baseline year of 2005, for example a 40-45% reduction from 2005. In the most recent inventory, annual emissions in 2005 were 759MtCO2e. This baseline year does not include emissions from LULUCF.

However, Canada can use “accounting contributions” from the LULUCF sector to meet its emissions targets. This involves using a “reference level approach” for managed forest and associated harvested wood products, meaning the government compares actual emissions and removals to a projected “reference level”. It uses a “net-net approach” for all the other LULUCF sub-sectors, meaning both emissions are removals are accounted for to get a net emissions figure.

For simplicity, Carbon Brief has left LULUCF contributions, which are relatively small, out of the historical emissions figures used in the first chart.

The CIMS modelling does not include emissions from LULUCF, so these are not included in the “Liberal” and “Conservative” emissions trajectories. However, in order to calculate the size of the emissions gap between the trajectories and Canada’s future targets, Carbon Brief simply added figures from government projections to these trajectories. These figures amount to emissions reductions of roughly 28-31MtCO2e annually from 2030 out to 2040.

In the second chart, Carbon Brief has used emissions data from the Canadian government’s most recent emissions projections, which appeared in its BTR, published at the end of 2024. These figures are slightly different from the ones in the most recent inventory, include LULUCF contributions and only go out to 2022.

Besides LULUCF contributions, the government reports separately on the impact of nature-based climate solutions, “agriculture measures” and credits purchased under the Western Climate Initiative (WCI), all of which are considered “additional measures” in its modelling. Nature-based solutions and “agriculture measures” cut another 12MtCO2e annually from 2030 onwards, whereas WCI credits are barely used. These figures are included in the “additional measures” government estimate in the second chart.

The post Analysis: Conservative election win could add 800m tonnes to Canada’s emissions by 2035 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Conservative election win could add 800m tonnes to Canada’s emissions by 2035

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

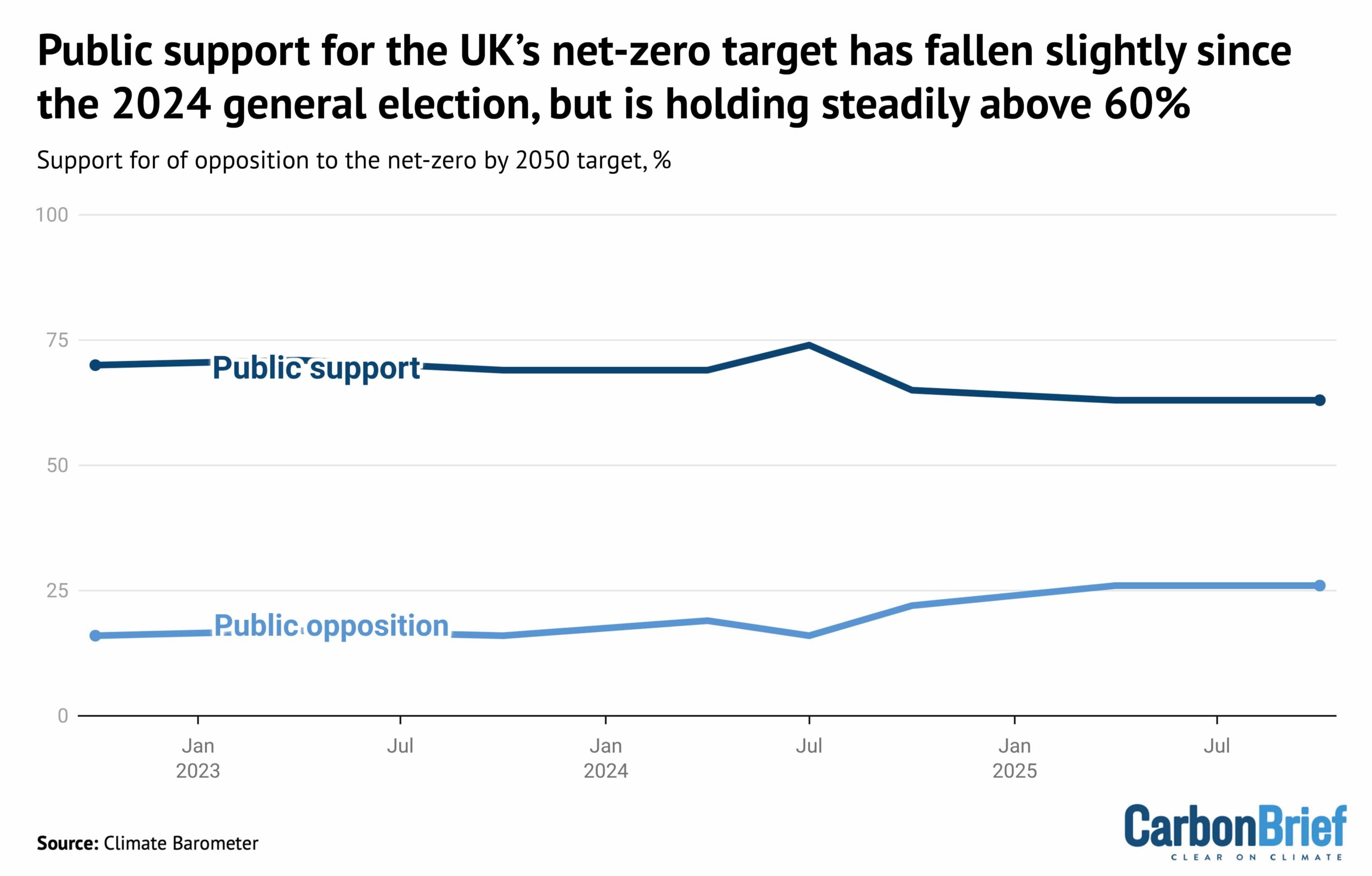

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

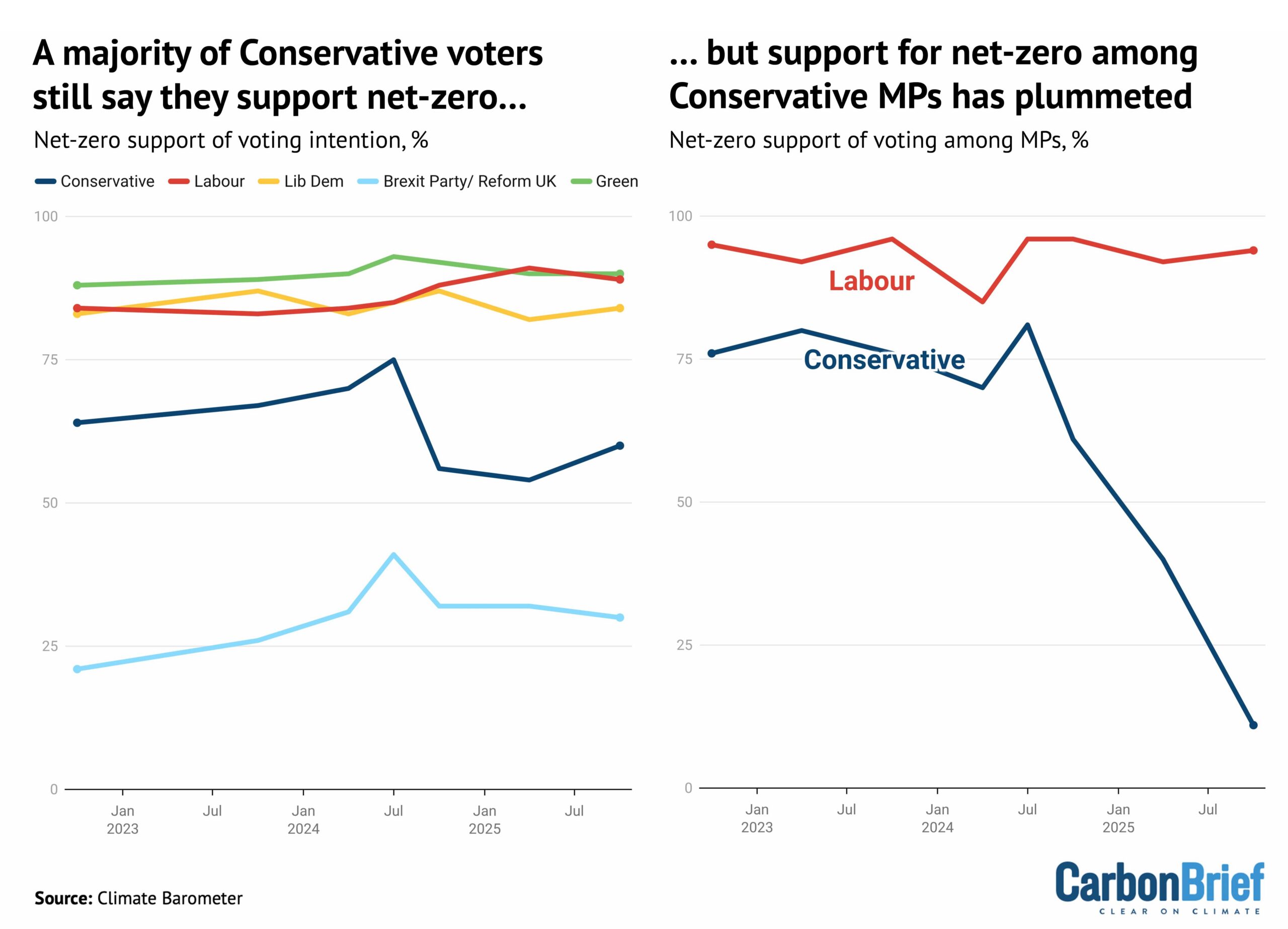

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

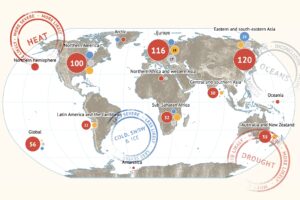

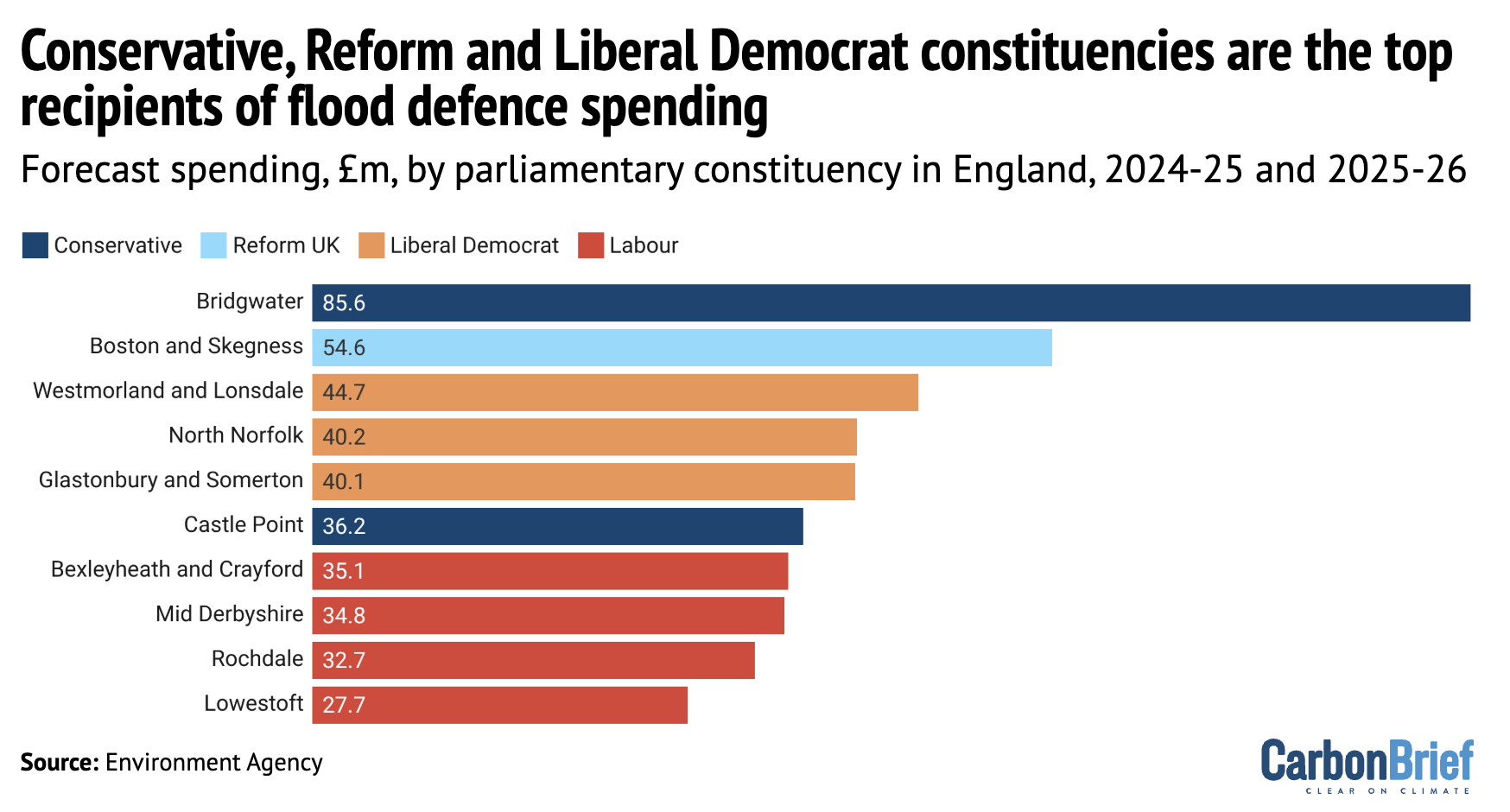

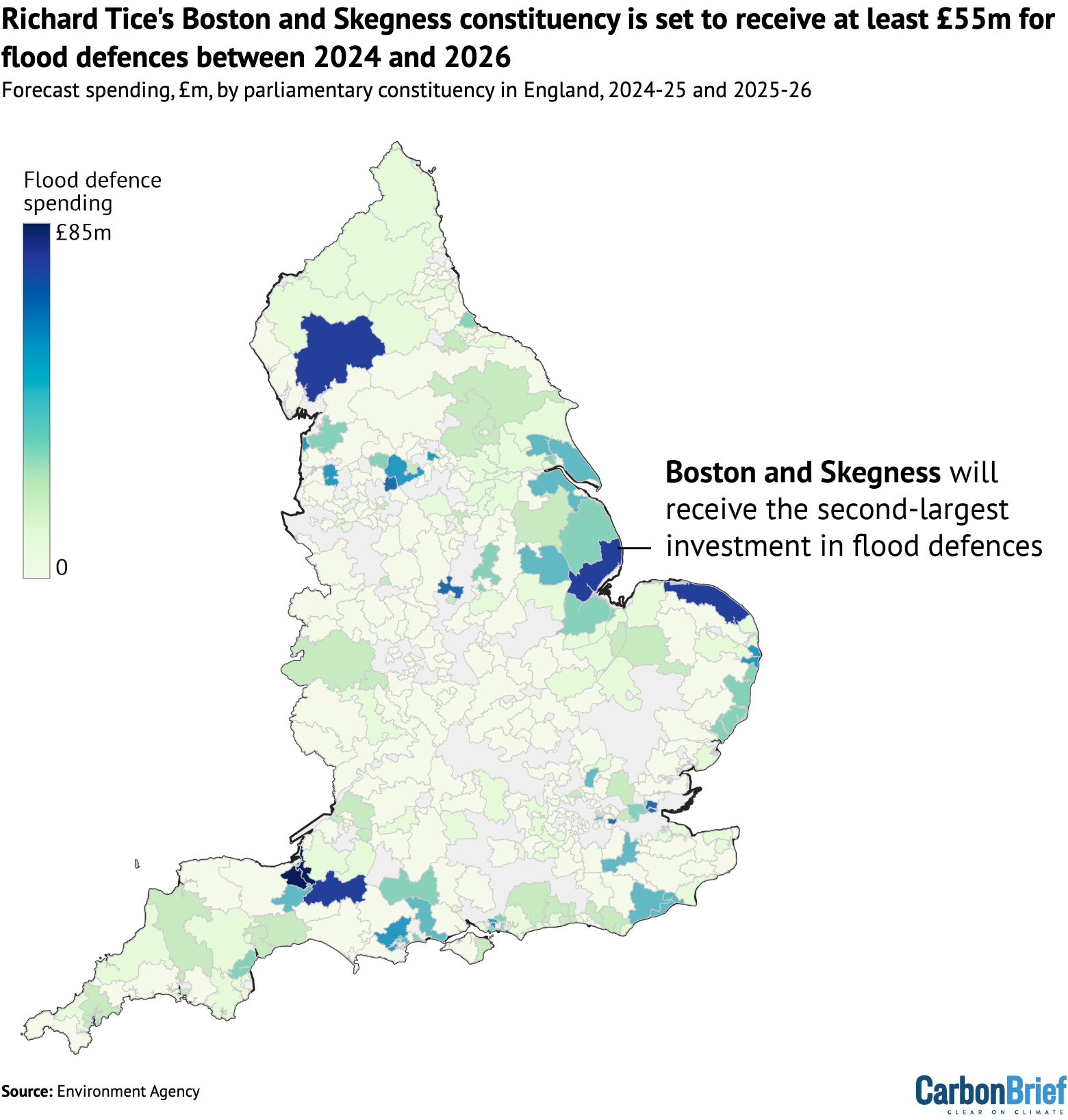

The Lincolnshire constituency held by Richard Tice, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of the hard-right Reform party, has been pledged at least £55m in government funding for flood defences since 2024.

This investment in Boston and Skegness is the second-largest sum for a single constituency from a £1.4bn flood-defence fund for England, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

Flooding is becoming more likely and more extreme in the UK due to climate change.

Yet, for years, governments have failed to spend enough on flood defences to protect people, properties and infrastructure.

The £1.4bn fund is part of the current Labour government’s wider pledge to invest a “record” £7.9bn over a decade on protecting hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses from flooding.

As MP for one of England’s most flood-prone regions, Tice has called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

He is also one of Reform’s most vocal opponents of climate action and what he calls “net stupid zero”. He denies the scientific consensus on climate change and has claimed, falsely and without evidence, that scientists are “lying”.

Flood defences

Last year, the government said it would invest £2.65bn on flood and coastal erosion risk management (FCERM) schemes in England between April 2024 and March 2026.

This money was intended to protect 66,500 properties from flooding. It is part of a decade-long Labour government plan to spend more than £7.9bn on flood defences.

There has been a consistent shortfall in maintaining England’s flood defences, with the Environment Agency expecting to protect fewer properties by 2027 than it had initially planned.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) has attributed this to rising costs, backlogs from previous governments and a lack of capacity. It also points to the strain from “more frequent and severe” weather events, such as storms in recent years that have been amplified by climate change.

However, the CCC also said last year that, if the 2024-26 spending programme is delivered, it would be “slightly closer to the track” of the Environment Agency targets out to 2027.

The government has released constituency-level data on which schemes in England it plans to fund, covering £1.4bn of the 2024-26 investment. The other half of the FCERM spending covers additional measures, from repairing existing defences to advising local authorities.

The map below shows the distribution of spending on FCERM schemes in England over the past two years, highlighting the constituency of Richard Tice.

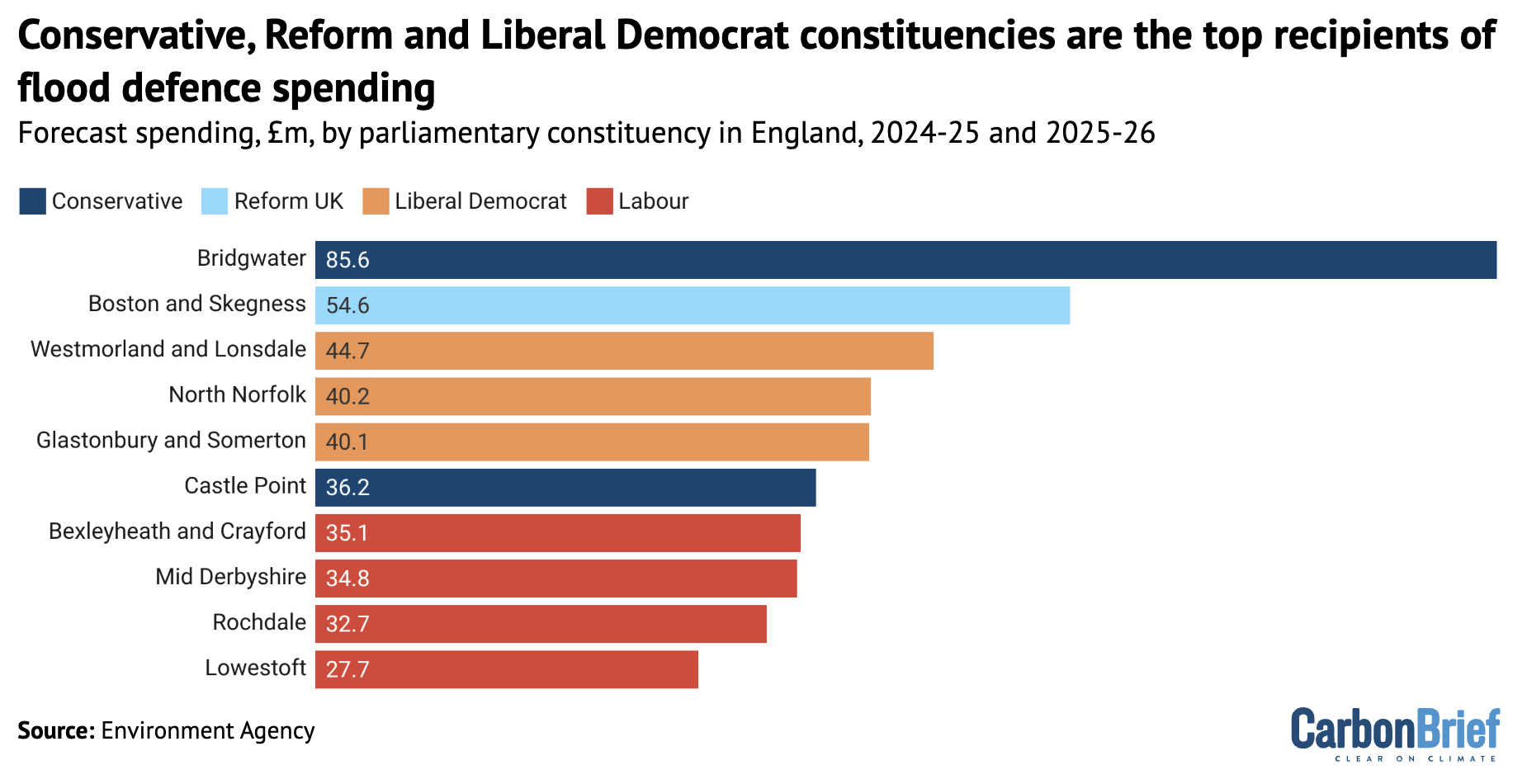

By far the largest sum of money – £85.6m in total – has been committed to a tidal barrier and various other defences in the Somerset constituency of Bridgwater, the seat of Conservative MP Ashley Fox.

Over the first months of 2026, the south-west region has faced significant flooding and Fox has called for more support from the government, citing “climate patterns shifting and rainfall intensifying”.

He has also backed his party’s position that “the 2050 net-zero target is impossible” and called for more fossil-fuel extraction in the North Sea.

Tice’s east-coast constituency of Boston and Skegness, which is highly vulnerable to flooding from both rivers and the sea, is set to receive £55m. Among the supported projects are beach defences from Saltfleet to Gibraltar Point and upgrades to pumping stations.

Overall, Boston and Skegness has the second-largest portion of flood-defence funding, as the chart below shows. Constituencies with Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs occupied the other top positions.

Overall, despite Labour MPs occupying 347 out of England’s 543 constituencies – nearly two-thirds of the total – more than half of the flood-defence funding was distributed to constituencies with non-Labour MPs. This reflects the flood risk in coastal and rural areas that are not traditional Labour strongholds.

Reform funding

While Reform has just eight MPs, representing 1% of the population, its constituencies have been assigned 4% of the flood-defence funding for England.

Nearly all of this money was for Tice’s constituency, although party leader Nigel Farage’s coastal Clacton seat in Kent received £2m.

Reform UK is committed to “scrapping net-zero” and its leadership has expressed firmly climate-sceptic views.

Much has been made of the disconnect between the party’s climate policies and the threat climate change poses to its voters. Various analyses have shown the flood risk in Reform-dominated areas, particularly Lincolnshire.

Tice has rejected climate science, advocated for fossil-fuel production and criticised Environment Agency flood-defence activities. Yet, he has also called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

This may reflect Tice’s broader approach to climate change. In a 2024 interview with LBC, he said:

“Where you’ve got concerns about sea level defences and sea level rise, guess what? A bit of steel, a bit of cement, some aggregate…and you build some concrete sea level defences. That’s how you deal with rising sea levels.”

While climate adaptation is viewed as vital in a warming world, there are limits on how much societies can adapt and adaptation costs will continue to increase as emissions rise.

The post Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

Greenhouse Gases

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Food inflation on the rise

DELUGE STRIKES FOOD: Extreme rainfall and flooding across the Mediterranean and north Africa has “battered the winter growing regions that feed Europe…threatening food price rises”, reported the Financial Times. Western France has “endured more than 36 days of continuous rain”, while farmers’ associations in Spain’s Andalusia estimate that “20% of all production has been lost”, it added. Policy expert David Barmes told the paper that the “latest storms were part of a wider pattern of climate shocks feeding into food price inflation”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

NO BEEF: The UK’s beef farmers, meanwhile, “face a double blow” from climate change as “relentless rain forces them to keep cows indoors”, while last summer’s drought hit hay supplies, said another Financial Times article. At the same time, indoor growers in south England described a 60% increase in electricity standing charges as a “ticking timebomb” that could “force them to raise their prices or stop production, which will further fuel food price inflation”, wrote the Guardian.

‘TINDERBOX’ AND TARIFFS: A study, covered by the Guardian, warned that major extreme weather and other “shocks” could “spark social unrest and even food riots in the UK”. Experts cited “chronic” vulnerabilities, including climate change, low incomes, poor farming policy and “fragile” supply chains that have made the UK’s food system a “tinderbox”. A New York Times explainer noted that while trade could once guard against food supply shocks, barriers such as tariffs and export controls – which are being “increasingly” used by politicians – “can shut off that safety valve”.

El Niño looms

NEW ENSO INDEX: Researchers have developed a new index for calculating El Niño, the large-scale climate pattern that influences global weather and causes “billions in damages by bringing floods to some regions and drought to others”, reported CNN. It added that climate change is making it more difficult for scientists to observe El Niño patterns by warming up the entire ocean. The outlet said that with the new metric, “scientists can now see it earlier and our long-range weather forecasts will be improved for it.”

WARMING WARNING: Meanwhile, the US Climate Prediction Center announced that there is a 60% chance of the current La Niña conditions shifting towards a neutral state over the next few months, with an El Niño likely to follow in late spring, according to Reuters. The Vibes, a Malaysian news outlet, quoted a climate scientist saying: “If the El Niño does materialise, it could possibly push 2026 or 2027 as the warmest year on record, replacing 2024.”

CROP IMPACTS: Reuters noted that neutral conditions lead to “more stable weather and potentially better crop yields”. However, the newswire added, an El Niño state would mean “worsening drought conditions and issues for the next growing season” to Australia. El Niño also “typically brings a poor south-west monsoon to India, including droughts”, reported the Hindu’s Business Line. A 2024 guest post for Carbon Brief explained that El Niño is linked to crop failure in south-eastern Africa and south-east Asia.

News and views

- DAM-AG-ES: Several South Korean farmers filed a lawsuit against the country’s state-owned utility company, “seek[ing] financial compensation for climate-related agricultural damages”, reported United Press International. Meanwhile, a national climate change assessment for the Philippines found that the country “lost up to $219bn in agricultural damages from typhoons, floods and droughts” over 2000-10, according to Eco-Business.

- SCORCHED GRASS: South Africa’s Western Cape province is experiencing “one of the worst droughts in living memory”, which is “scorching grass and killing livestock”, said Reuters. The newswire wrote: “In 2015, a drought almost dried up the taps in the city; farmers say this one has been even more brutal than a decade ago.”

- NOUVELLE VEG: New guidelines published under France’s national food, nutrition and climate strategy “urged” citizens to “limit” their meat consumption, reported Euronews. The delayed strategy comes a month after the US government “upended decades of recommendations by touting consumption of red meat and full-fat dairy”, it noted.

- COURTING DISASTER: India’s top green court accepted the findings of a committee that “found no flaws” in greenlighting the Great Nicobar project that “will lead to the felling of a million trees” and translocating corals, reported Mongabay. The court found “no good ground to interfere”, despite “threats to a globally unique biodiversity hotspot” and Indigenous tribes at risk of displacement by the project, wrote Frontline.

- FISH FALLING: A new study found that fish biomass is “falling by 7.2% from as little as 0.1C of warming per decade”, noted the Guardian. While experts also pointed to the role of overfishing in marine life loss, marine ecologist and study lead author Dr Shahar Chaikin told the outlet: “Our research proves exactly what that biological cost [of warming] looks like underwater.”

- TOO HOT FOR COFFEE: According to new analysis by Climate Central, countries where coffee beans are grown “are becoming too hot to cultivate them”, reported the Guardian. The world’s top five coffee-growing countries faced “57 additional days of coffee-harming heat” annually because of climate change, it added.

Spotlight

Nature talks inch forward

This week, Carbon Brief covers the latest round of negotiations under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which occurred in Rome over 16-19 February.

The penultimate set of biodiversity negotiations before October’s Conference of the Parties ended in Rome last week, leaving plenty of unfinished business.

The CBD’s subsidiary body on implementation (SBI) met in the Italian capital for four days to discuss a range of issues, including biodiversity finance and reviewing progress towards the nature targets agreed under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

However, many of the major sticking points – particularly around finance – will have to wait until later this summer, leaving some observers worried about the capacity for delegates to get through a packed agenda at COP17.

The SBI, along with the subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) will both meet in Nairobi, Kenya, later this summer for a final round of talks before COP17 kicks off in Yerevan, Armenia, on 19 October.

Money talks

Finance for nature has long been a sticking point at negotiations under the CBD.

Discussions on a new fund for biodiversity derailed biodiversity talks in Cali, Colombia, in autumn 2024, requiring resumed talks a few months later.

Despite this, finance was barely on the agenda at the SBI meetings in Rome. Delegates discussed three studies on the relationship between debt sustainability and implementation of nature plans, but the more substantive talks are set to take place at the next SBI meeting in Nairobi.

Several parties “highlighted concerns with the imbalance of work” on finance between these SBI talks and the next ones, reported Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Lim Li Ching, senior researcher at Third World Network, noted that tensions around finance permeated every aspect of the talks. She told Carbon Brief:

“If you’re talking about the gender plan of action – if there’s little or no financial resources provided to actually put it into practice and implement it, then it’s [just] paper, right? Same with the reporting requirements and obligations.”

Monitoring and reporting

Closely linked to the issue of finance is the obligations of parties to report on their progress towards the goals and targets of the GBF.

Parties do so through the submission of national reports.

Several parties at the talks pointed to a lack of timely funding for driving delays in their reporting, according to ENB.

A note released by the CBD Secretariat in December said that no parties had submitted their national reports yet; by the time of the SBI meetings, only the EU had. It further noted that just 58 parties had submitted their national biodiversity plans, which were initially meant to be published by COP16, in October 2024.

Linda Krueger, director of biodiversity and infrastructure policy at the environmental not-for-profit Nature Conservancy, told Carbon Brief that despite the sparse submissions, parties are “very focused on the national report preparation”. She added:

“Everybody wants to be able to show that we’re on the path and that there still is a pathway to getting to 2030 that’s positive and largely in the right direction.”

Watch, read, listen

NET LOSS: Nigeria’s marine life is being “threatened” by “ghost gear” – nets and other fishing equipment discarded in the ocean – said Dialogue Earth.

COMEBACK CAUSALITY: A Vox long-read looked at whether Costa Rica’s “payments for ecosystem services” programme helped the country turn a corner on deforestation.

HOMEGROWN GOALS: A Straits Times podcast discussed whether import-dependent Singapore can afford to shelve its goal to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030.

‘RUSTING’ RIVERS: The Financial Times took a closer look at a “strange new force blighting the [Arctic] landscape”: rivers turning rust-orange due to global warming.

New science

- Lakes in the Congo Basin’s peatlands are releasing carbon that is thousands of years old | Nature Geoscience

- Natural non-forest ecosystems – such as grasslands and marshlands – were converted for agriculture at four times the rate of land with tree cover between 2005 and 2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Around one-quarter of global tree-cover loss over 2001-22 was driven by cropland expansion, pastures and forest plantations for commodity production | Nature Food

In the diary

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean | Brasília

- 5 March: Nepal general elections

- 9-20 March: First part of the thirty-first session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) | Kingston, Jamaica

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits