The term “global warming” is typically used to describe increasing global temperatures as a result of human emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases.

However, unusually cold events are often portrayed as being made worse by human activity, as a result of increased variability or a disruption of the “polar vortex” in a fast-warming world.

There is significant debate in the scientific community about whether rapid Arctic warming and sea ice loss could disrupt atmospheric circulation patterns and lead to cold-air outbreaks in the northern hemisphere mid-latitude regions.

In a new analysis, Carbon Brief shows that few places in the world have seen an increase in extreme cold days over the past 55 years.

If climate change is influencing atmospheric circulation, any effects on extreme cold appear to be more than compensated by the rapid winter warming the world has experienced.

A controversial hypothesis

In an episode of Marketplace’s How We Survive podcast last year, the host – US radio journalist Kai Ryssdal – noted that climate change is expected to cause “hotter hots [and] colder colds in unexpected parts of the world”.

This is not an uncommon sentiment, with the media commonly attributing extreme cold events to human activity, particularly during episodes of bitter cold or polar-vortex events.

Some researchers have argued that these extreme cold snaps might be becoming more frequent due to reduced sea ice and Arctic amplification – the phenomenon where the Arctic warms more quickly than the global average.

At the core of the hypothesis that Arctic warming could influence mid-latitude cold extremes is the fact that a rapidly warming Arctic changes the temperature difference between the poles and the equator.

Normally, the strong contrast in temperature between these regions drives key patterns of atmospheric circulation, including the jet stream. According to proponents of this theory, when Arctic temperatures rise faster than those farther south, atmospheric circulation can weaken, meander, or buckle more frequently. As a result, cold polar air can spill down into areas that are usually less frigid.

A related argument focuses on how diminished sea ice – particularly in the Barents and Kara seas – might disrupt the atmosphere. Less sea ice means more heat and moisture escapes from the ocean surface into the air, which can potentially alter weather patterns downstream. This can boost the odds of “blocking high” weather systems, or unusual circulation patterns that pull cold air into mid-latitudes.

However, there are relatively few studies that attribute an increase in cold extremes – or an individual extreme cold event – to human activity.

Carbon Brief’s attribution map – which charts extreme weather events around the world and their links to human-caused warming – includes 33 studies that examine extreme cold events specifically.

Of these, 24 studies found that the extreme cold was made less likely due to climate change, six found no discernible human influence and three found insufficient data to conclude either way. Only one extreme event attribution study in the database found that a cold extreme – severe frosts in Western Australia in 2016 – was made more likely due to climate change. However, even that study noted that “warmer temperatures may have offset or countered this effect of the circulation driver”.

Many climate scientists disagree with the hypothesis that warming could lead to increased cold outbreaks, arguing that cold extremes are decreasing overall in a warming world.

Others contend that causality cannot yet be proved and that both models and observations provide limited support for a significant role of climate change in mid-latitude cold events.

In addition, observed data reveals that, although cold spells still occur, they have become less frequent and less intense over recent decades. Most modeling studies do not consistently reproduce more frequent or severe cold outbreaks. Instead, they often show that the overall warming trend dominates, making cold extremes rarer over time.

This suggests that, if there were a connection between climate change and extreme cold events, the long-term warming trend will still likely lead to fewer, milder cold outbreaks – and that any effect from Arctic amplification would be relatively small.

Have any regions experienced increased cold events?

To help assess the effects of climate change on extreme cold events, Carbon Brief used gridded daily minimum global temperature data from Berkeley Earth to calculate how the temperatures of the coldest 5% of the days of the year have changed since the 1970s.

Minimum daily temperatures reflect the single coldest measurement taken over the course of the day. (While the coldest 5% of days is a somewhat arbitrary number, the results are largely similar for the coldest 10%, 5%, 2%, 1%, or the single coldest day of the year.)

The figure below shows the results for every one-by-one degree latitude-longitude grid cell on the Earth’s land (a size approximately equivalent to 100km by 100km). Grid cells coloured red experienced a decrease in extreme cold days, while those coloured blue had more extreme cold days.

The vast majority of the planet has seen a strong decrease in extreme cold events, with the largest declines seen in high-latitude northern hemisphere regions (which have also experienced the fastest rate of warming overall).

The few regions that have seen an increase in extreme cold events tend to be those with the slowest average rates of warming, including India, South Africa and Antarctica.

In India, this has likely been influenced by rapid increases in air pollution – particularly cooling sulfate aerosols – over this period. Causes of more extreme cold events in Antarctica are less clear, though it is possible that they could be linked to the seasonal loss of ozone layer over the past 50 years.

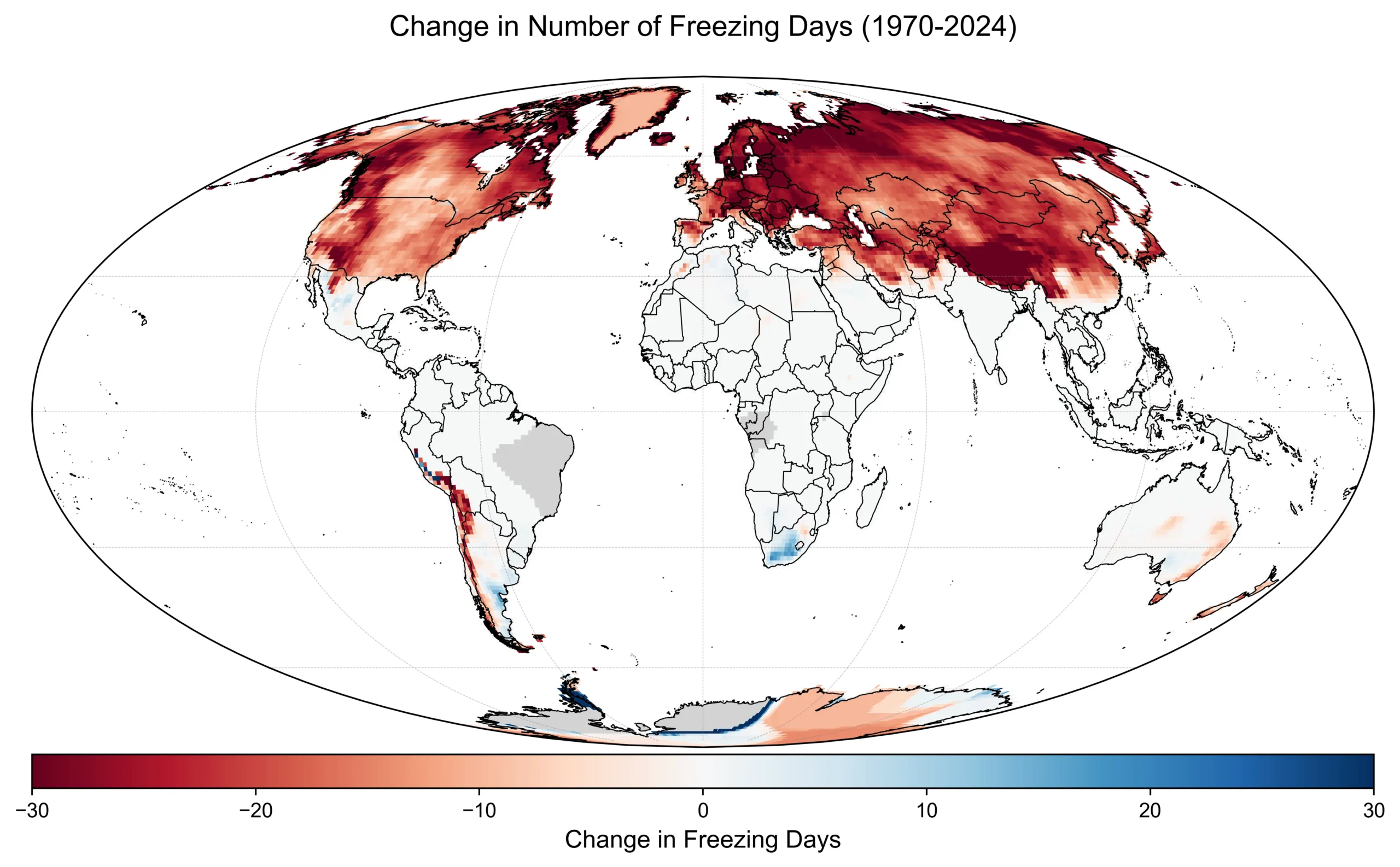

Another way to assess changes in cold events is to look at the change in the number of days where any hour of the day – that is, the daily minimum temperature – is below freezing (0C, 32F). The map below shows the change in average annual freezing days between 1970 and 2024.

The map shows dramatic shifts in the number of freezing days in much of the high-latitude northern hemisphere, with nearly a month fewer freezing days over the Himalayas, eastern Europe and parts of Canada and the western US over the past 50 years.

(White areas on the graph – such as much of the tropics and subtropics – represent regions of the world where temperatures below freezing almost never occur and thus changes over time cannot be calculated.)

Fewer cold outbreaks in the US

A sizable portion of the academic research on cold outbreaks has been focused on the contiguous US, as it is a region prone to occasional extreme cold conditions caused by intrusions of Arctic air.

The map below shows there has been a warming trend in the coldest days of the year across virtually the entire US over the past 50 years.

This suggests that the effect of Arctic amplification on cold-air patterns is smaller than the strong winter warming trend.

Almost no regions of the US have seen a cooling trend in the 5% coldest days of the year – and higher latitude regions have tended to experience the fastest winter warming.

There has been a slight cooling trend in the coldest days of the year in northern Mexico and slower warming in California, Arizona, southern New Mexico and southern Texas.

Similarly, the figure below examines the change in days where minimum temperatures are below freezing in the US.

It shows that there are, on average, 13 fewer days below freezing each year compared to the 1970s. Or, to put it another way, there is half a month where daily minimum temperatures are no longer cold enough for icy and snowy conditions to occur.

Increasingly rare cold spells

The latest climate models overwhelmingly project that cold extremes will continue to diminish as greenhouse gas concentrations rise.

This means that, even if certain patterns occasionally transport freezing polar air southward, winters on the whole are likely to be milder than in the past.

However, the scientific understanding of precisely how Arctic warming might – or might not – influence mid-latitude weather is still evolving.

Researchers continue to refine models, incorporate better reanalysis data and examine how changes in atmospheric circulation dynamics might play out under different scenarios. Additional data – especially over multiple decades – will help clarify whether the Arctic’s role in mid-latitude cold extremes is significant or overstated.

For now, observations over the past 50 years generally show a world with fewer cold extremes – and projections point toward increasingly rare cold spells in the future.

The post Factcheck: Climate change is not making extreme cold more common appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Factcheck: Climate change is not making extreme cold more common

Climate Change

A Tiny Caribbean Island Sued the Netherlands Over Climate Change, and Won

The case shows that climate change is a fundamental human rights violation—and the victory of Bonaire, a Dutch territory, could open the door for similar lawsuits globally.

From our collaborating partner Living on Earth, public radio’s environmental news magazine, an interview by Paloma Beltran with Greenpeace Netherlands campaigner Eefje de Kroon.

A Tiny Caribbean Island Sued the Netherlands Over Climate Change, and Won

Climate Change

Greenpeace organisations to appeal USD $345 million court judgment in Energy Transfer’s intimidation lawsuit

SYDNEY, Saturday 28 February 2026 — Greenpeace International and Greenpeace organisations in the US announce they will seek a new trial and, if necessary, appeal the decision with the North Dakota Supreme Court following a North Dakota District Court judgment today awarding Energy Transfer (ET) USD $345 million.

ET’s SLAPP suit remains a blatant attempt to silence free speech, erase Indigenous leadership of the Standing Rock movement, and punish solidarity with peaceful resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Greenpeace International will also continue to seek damages for ET’s bullying lawsuits under EU anti-SLAPP legislation in the Netherlands.

Mads Christensen, Greenpeace International Executive Director said: “Energy Transfer’s attempts to silence us are failing. Greenpeace International will continue to resist intimidation tactics. We will not be silenced. We will only get louder, joining our voices to those of our allies all around the world against the corporate polluters and billionaire oligarchs who prioritise profits over people and the planet.

“With hard-won freedoms under threat and the climate crisis accelerating, the stakes of this legal fight couldn’t be higher. Through appeals in the US and Greenpeace International’s groundbreaking anti-SLAPP case in the Netherlands, we are exploring every option to hold Energy Transfer accountable for multiple abusive lawsuits and show all power-hungry bullies that their attacks will only result in a stronger people-powered movement.”

The Court’s final judgment today rejects some of the jury verdict delivered in March 2025, but still awards hundreds of millions of dollars to ET without a sound basis in law. The Greenpeace defendants will continue to press their arguments that the US Constitution does not allow liability here, that ET did not present evidence to support its claims, that the Court admitted inflammatory and irrelevant evidence at trial and excluded other evidence supporting the defense, and that the jury pool in Mandan could not be impartial.[1][2]

ET’s back-to-back lawsuits against Greenpeace International and the US organisations Greenpeace USA (Greenpeace Inc.) and Greenpeace Fund are clear-cut examples of SLAPPs — lawsuits attempting to bury nonprofits and activists in legal fees, push them towards bankruptcy and ultimately silence dissent.[3] Greenpeace International, which is based in the Netherlands, is pursuing justice in Europe, with a suit against ET under Dutch law and the European Union’s new anti-SLAPP directive, a landmark test of the new legislation which could help set a powerful precedent against corporate bullying.[4]

Kate Smolski, Program Director at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, said: “This is part of a worrying trend globally: fossil fuel corporations are increasingly using litigation to attack and silence ordinary people and groups using the law to challenge their polluting operations — and we’re not immune to these tactics here in Australia.

“Rulings like this have a chilling effect on democracy and public interest litigation — we must unite against these silencing tactics as bad for Australians and bad for our democracy. Our movement is stronger than any corporate bully, and grows even stronger when under attack.”

Energy Transfer’s SLAPPs are part of a wave of abusive lawsuits filed by Big Oil companies like Shell, Total, and ENI against Greenpeace entities in recent years.[3] A couple of these cases have been successfully stopped in their tracks. This includes Greenpeace France successfully defeating TotalEnergies’ SLAPP on 28 March 2024, and Greenpeace UK and Greenpeace International forcing Shell to back down from its SLAPP on 10 December 2024.

-ENDS-

Images available in Greenpeace Media Library

Notes:

[1] The judgment entered by North Dakota District Court Judge Gion follows a jury verdict finding Greenpeace entities liable for more than US$660 million on March 19, 2025. Judge Gion subsequently threw out several items from the jury’s verdict, reducing the total damages to approximately US$345 million.

[2] Public statements from the independent Trial Monitoring Committee

[3] Energy Transfer’s first lawsuit was filed in federal court in 2017 under the RICO Act – the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a US federal statute designed to prosecute mob activity. The case was dismissed in 2019, with the judge stating the evidence fell “far short” of what was needed to establish a RICO enterprise. The federal court did not decide on Energy Transfer’s claims based on state law, so Energy Transfer promptly filed a new case in a North Dakota state court with these and other state law claims.

[4] Greenpeace International sent a Notice of Liability to Energy Transfer on 23 July 2024, informing the pipeline giant of Greenpeace International’s intention to bring an anti-SLAPP lawsuit against the company in a Dutch Court. After Energy Transfer declined to accept liability on multiple occasions (September 2024, December 2024), Greenpeace International initiated the first test of the European Union’s anti-SLAPP Directive on 11 February 2025 by filing a lawsuit in Dutch court against Energy Transfer. The case was officially registered in the docket of the Court of Amsterdam on 2 July, 2025. Greenpeace International seeks to recover all damages and costs it has suffered as a result of Energy Transfers’s back-to-back, abusive lawsuits demanding hundreds of millions of dollars from Greenpeace International and the Greenpeace organisations in the US. The next hearing in the Court of Amsterdam is scheduled for 16 April, 2026.

Media contact:

Kate O’Callaghan on 0406 231 892 or kate.ocallaghan@greenpeace.org

Climate Change

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

The Trump administration’s relentless rollback of public health and environmental protections has allowed widespread toxic exposures to flourish, warn experts who helped implement safeguards now under assault.

In a new report that outlines a dozen high-risk pollutants given new life thanks to weakened, delayed or rescinded regulations, the Environmental Protection Network, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group of hundreds of former Environmental Protection Agency staff, warns that the EPA under President Donald Trump has abandoned the agency’s core mission of protecting people and the environment from preventable toxic exposures.

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits