The spotless white-sand beach of Le Lamantin luxury resort in Saly, about 90 kilometres south of Senegal’s capital Dakar, is lined with neat rows of sun loungers and parasols. Here, holidaymakers enjoy jet-skiing, catamaran-sailing and spa therapy, unaware that their hotel is benefiting from international climate finance channelled through the World Bank Group.

Just a few kilometres further south, however, local fishermen in Mbour, the country’s second-largest fishing port, are struggling. The beaches where they keep their boats are being progressively eaten away by rising seas that also threaten their homes.

The stark contrast between the neighbouring coastal areas highlights how global funding for climate projects – largely taxpayers’ money from rich countries – often fails to help those shouldering the burden of warming impacts, especially when it is being used to mobilise more private investment for green aims.

“They prioritise Saly because the hotels are wealthy,” said Saliou Diouf, a retired fisherman who lost his house in Mbour to encroaching waves. “The World Bank should help the most vulnerable.”

Le Lamantin is one of a dozen upscale hotels in sub-Saharan Africa acquired by Mauritius-based Kasada Hospitality Fund LP – run by Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund and multinational hotel giant Accor – which it is revamping in accordance with EDGE, a green building certification created by the World Bank.

Kasada was granted over $190 million in guarantees by the World Bank Group’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), and loans of up to $160 million by its private-sector lender, the International Finance Corporation, to help it snap up hotels across Kenya, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Rwanda, Namibia and Senegal, and spruce them up as Accor brands like Mövenpick.

The Mövenpick Resort Lamantin Saly, where a standard hotel room costs about £220 a night. (Photo: Jack Thompson)

MIGA, the little-known insurance arm of the World Bank Group, has counted its backing for the hotels as part of its climate efforts for the past three years, according to annual sustainability reports.

The five-star resort in Senegal, where rooms cost at least £220 a night ($270), is being refurbished to consume at least 20% less energy and water than other comparable buildings by its owner Kasada, which expects it to obtain EDGE certification this year.

Teresa Anderson, global lead on climate justice for ActionAid International, told Climate Home it is “shocking that what little funds there are for climate action are benefiting luxury hotels”.

Ver esta publicación en Instagram

“Climate finance must be used to help those most vulnerable – not to help the world’s wealthiest add a climate hashtag to their Instagram posts by the pool,” she said.

MIGA told Climate Home its support for Kasada is primarily aimed at developing Senegal’s tourism sector and creating jobs, adding that refurbishing hotels can also have beneficial climate impacts and play an important role in decarbonising the hospitality industry.

Mbour, just a few miles from the pristine beaches of Saly, is the second-largest fishing hub in Senegal with 11,000 fishers. (Photo: Jack Thompson)

‘The money is missing’

In nearby Mbour, however, the fishing community feels left behind.

“I was born here, I grew up here – when I was a child, the sea only came up to the last pole,” Diouf told Climate Home, pointing to the remnants of a Portuguese-built pontoon used to moor colonial ships in the 1800s.

In just one generation, he said, the sea has gobbled up more than 100 metres of beach in Mbour, forcing 30 families to abandon their houses and threatening hundreds more. A quarter of the Senegalese coastline – home to 60% of the population – is at high risk of erosion.

Mbour’s fast-disappearing shore is a crisis for its 11,000 fishers as big swells destroy their boats, crammed into the remaining patch of sand.

But in Saly, it’s a different story. Here, between 2017 and 2022, under a separate project, the World Bank invested $74 million in beach protection, building 19 stone walls, groynes and breakwaters to reclaim 8-9 kilometres of hotel-lined beachfront, popular with tourists.

The World Bank Group said the project helped preserve around 15,000 direct and indirect jobs by saving tourism infrastructure, while also protecting two fishing villages in Saly.

Satellite data shows the changing coastline in Saly (north), where protective infrastructure was developed, and Mbour (south), which has none. (Photo: Modified Copernicus Sentinel data [2024]/Sentinel Hub)

Kasada told Climate Home, meanwhile, that Le Lamantin hotel has so far created about 50 direct jobs of different types for people living near Saly, with MIGA also pointing to indirect employment stimulated by the resort such as agriculture, handicrafts and transport.

The World Bank Group (WBG) said its units work together to avoid trade-offs. “It’s not to either support hotels and the tourism sector as a driver of development, or to enhance the resilience of local communities – the WBG does both,” it said in a written response to Climate Home.

But fishermen in Mbour – which was outside the scope of the Saly coastal protection infrastructure project – are not benefiting from that approach, and even say the works in Saly have exacerbated erosion in their area. The Mbour artisanal fisheries council has devised a climate adaptation strategy to address the problem.

One of its coordinators, Moustapha Senghor, said seawalls and breakwaters are needed, but there are no funds for what would amount to “a colossal investment”. “We know exactly what we need to do, but the money is missing,” he said.

Sea level rise is threatening beach-side homes and swallowing coconut trees that protect the coastline in Mbour, Senegal. (Photo: Jack Thompson)

Private-sector trillions

Governments and climate justice activists are putting pressure on the World Bank to significantly step up its role in funding climate projects, especially to help the most vulnerable countries and communities.

For the past three years, a group of countries led by Barbados’ Prime Minister Mia Mottley has called for reforms so that the bank can better address climate change.

At the same time, wealthy nations have been reluctant to inject more capital into its coffers, while attempts at tinkering with the balance sheet to squeeze out more climate cash only go so far.

For World Bank Group President Ajay Banga, the real solution lies in greater private-sector involvement, using scarce public money as a lever to help mobilise huge dollar sums for climate and development goals this decade.

“We know that governments and multilateral institutions and philanthropies all working together will still fall short of providing the trillions that we will require annually for climate, for fragility, for inequality in the world. We therefore need the private sector,” Banga told media ahead of this week’s annual Spring Meetings of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

MIGA’s guarantees can be a key driver of climate investments in developing countries. (Graphic: Fanis Kollias)

Following suggestions from a group of CEOs convened by Banga, the World Bank Group announced in February a major overhaul of its guarantee business to enable “improved access and faster execution”. The goal is to triple issuances, including those from MIGA, to $20 billion by 2030, with a significant proportion of that expected to support green projects.

MIGA – as a provider of guarantees aimed at encouraging private capital into developing countries – may not be the obvious choice to help low-income communities like Mbour’s fishers.

But, in its 2023 sustainability report, the agency wrote: “because the poorest are the most vulnerable to climate change, MIGA is working to mobilize more private finance to scale up climate adaptation, resilience and preparedness”.

Last year, less than one percent of MIGA’s total guarantees directly supported climate adaptation measures, according to its annual report.

The guarantees generally act as a form of political risk insurance, making an investment less risky and giving companies access to cheaper loans as a result.

MIGA’s 2023 sustainability report showcases the Kasada-owned hotels as an example of its efforts to “rapidly ramp up” private capital for climate action, with the agency providing its highest volume of climate finance last year.

Struggle to fund adaptation

But some experts argue the World Bank Group should be targeting its efforts more closely on communities who are struggling to survive as global warming exacerbates extreme weather and rising seas.

Vijaya Ramachandran, a director at the Breakthrough Institute, a California-based environmental research centre, said projects like the Kasada-backed hotels are “not where the dollars are best spent from a climate perspective”.

Ramachandran, a former World Bank economist, co-authored a study last year analysing the climate portfolio of the bank’s public-sector lending arms, which exclude MIGA. It found a lack of clarity over what constitutes a climate project and showed that hundreds of projects had been tagged as climate finance despite having little to do with emissions-reduction efforts or adaptation.

Ramachandran told Climate Home that, in the case of MIGA’s backing for the African hotels, Kasada “should just be doing the energy saving itself as part of its own efforts to address climate change”.

Holidaymakers enjoy a spacious, ocean-side pool at the five-star Le Lamantin resort in Saly, Senegal. (Photo: Jack Thompson).

Olivier Granet and David Damiba, managing partners of Kasada Capital Management, told Climate Home the hotel investment fund had always planned to be “a leader in energy and water efficiency in its properties”.

But, they added, the financial and technical support of MIGA and the IFC had helped them implement their strategy “further and more easily”, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eight Kasada-owned hotels have already been certified under EDGE and the rest are expected to achieve the standard this year, they noted.

Ramachandran said making hotels energy-efficient is a good thing – “but from a public finance perspective, for poorer African countries the focus should be on adaptation and making them more resilient”.

Developing countries need an estimated $387 billion a year to carry out their current adaptation plans, but in 2021 they received only $24.6 billion in international adaptation finance, according to the latest figures published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

MIGA to miss climate target?

Once regarded by campaigners as the “World Bank’s dirtiest wing” for its support of fossil fuels, MIGA has come under mounting pressure to shift its subsidies in a greener direction, in line with broader institutional goals.

In response, the agency has committed to throw more of its financial weight behind projects that aim to cut greenhouse gas emissions or alleviate the impacts of climate change.

In 2020, it revealed a plan to dedicate at least 35% of its guarantees to climate projects on average from fiscal year 2021 through 2025, embracing a target set by the wider World Bank Group.

MIGA conceded at the time this would be “a challenge” – and it now looks likely to fall short of the goal. In 2023, climate finance represented 28% of its guaranteed investments.

According to the agency’s 2023 sustainability report, 31 out of 40 projects it supported with guarantees last year had a climate mitigation or adaptation component, but it did not disclose what percentage of each was counted as climate finance.

Meanwhile, over the last three years, MIGA has backed three gas-fired power plants in Mozambique and Bangladesh, while it is also planning to support an additional one in Togo.

In monetary terms, MIGA’s annual provision of climate guarantees has risen from just over $1 billion in 2019 to $1.5 billion in 2023, pushing up the total size of its climate portfolio to $8.4 billion. But the headline numbers only paint a partial picture, clouded by a lack of transparency in the data.

MIGA’s portfolio of climate investments has grown in the past six years. (Photo: MIGA Climate Change)

In response to Climate Home’s request for a full list of MIGA’s climate projects, the agency said it could not disclose the information for confidentiality reasons.

“Our clients are private-sector investors or financiers, and we do not have agreement to release disaggregated information about their investments and financing,” a MIGA spokesperson said.

The only clues about the make-up of MIGA’s climate portfolio come in its glossy annual sustainability reports, which highlight a handful of initiatives.

Climate Home News reviewed these reports from the last three available years – 2021, 2022 and 2023 – and tracked highlighted projects, which are framed as positive examples of climate finance.

Motorways and elite universities

They show that support for renewable energy made up a quarter of MIGA’s climate guarantees in 2023.

But its track record of climate investments raises questions about the agency’s criteria for designating projects as climate finance and how it allocates those resources to help people most in need, experts said.

Karen Mathiasen, a former director of the multilateral development bank office in the US Treasury, said MIGA should not be using its resources to expand investment in things like luxury hotels and then counting them as climate finance.

“There is a real problem in the World Bank Group with greenwashing,” added Mathiasen, who is now a project director with the Center for Global Development.

MIGA said it calculates the climate co-benefits from its projects using the same methodologies as other multilateral development banks, and applies them consistently according to a “rigorous internal consultation and review process”.

Large infrastructure projects feature heavily in MIGA’s climate portfolio.

For example, a group of international banks, including JP Morgan, Banco Santander and Credit Agricole, have received a total of €1.4 billion in guarantees to bankroll the construction of a new motorway in Serbia, in an area prone to severe flooding.

The 112-km dual-carriageway, in the West Morava river valley, is implementing measures to reduce flood risk, including river regulation – and so was counted as climate finance.

In 2022, MIGA’s largest climate guarantee – worth €570 million ($615 million) – helped finance the construction of a new campus in Morocco’s capital Rabat for the Mohammed VI Polytechnic, a private university owned by mining and fertiliser company OCP Group and frequented by the country’s elite.

According to MIGA, the project would seek to obtain LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) green-building certification “for key facilities”, and include hydraulic structures to enhance the climate resilience of the campus.

Similarly, support for a new hospital in Gaziantep, Turkey, was tagged as 100% climate finance because it features energy efficiency measures and flood drainage works.

In 2023, just under half of MIGA’s climate guarantees went towards “greening” the financial sector in mainly middle-income countries like Argentina, Colombia, Hungary, Algeria and Botswana.

These guarantees are intended to help local banks free up more capital and boost loans to climate projects, although in some cases they are only expected to do so on a “best effort basis” involving no strict obligation, according to MIGA’s annual reports.

MIGA said this clause is included for regulatory reasons and requires banks to “take all necessary actions to provide climate loan commitments” as far as is “commercially reasonable”.

UN climate chief calls for “quantum leap in climate finance”

Call for clarity

Ramachandran of the Breakthrough Institute said MIGA should demonstrate the outcomes of its climate finance projects “in terms of reduced emissions or of improved resilience, (and) what the overarching strategy is to make sure the money is best spent”.

“Instead the focus is simply on dollar amounts,” she added – a criticism rejected by the World Bank Group.

MIGA said it supports projects in all sectors that contribute to development and enables the inclusion of emissions-cutting and climate adaptation measures in their design and operation.

Former U.S. official Mathiasen believes MIGA could be a powerful engine to mobilise more private money for climate action, but said it needs a cultural change to focus more on results rather than numerical targets which give staff an incentive to “pump up the numbers”.

“A little bit of an add-on – that is not a climate project. There needs to be clear, transparent criteria of what constitutes a climate project,” she said.

(Reporting by Jack Thompson in Senegal and Matteo Civillini in London; additional reporting by Sebastian Rodriguez; editing by Megan Rowling, Sebastian Rodriguez and Joe Lo; graphics by Fanis Kollias)

The post World Bank climate funding greens African hotels while fishermen sink appeared first on Climate Home News.

World Bank climate funding greens African hotels while fishermen sink

Climate Change

Climate at Davos: Clean tech powers on despite policy wobbles

The annual World Economic Forum is underway in the Swiss ski resort of Davos, providing a snowy backdrop for leaders and CEOs to opine on international affairs, including close to 65 heads of state and government On Wednesday afternoon, US President Donald Trump is set to speak, with all eyes on whether he will further stoke a potential US-European trade war over his bid to grab Greenland.

Despite geopolitics grabbing the limelight, there are panels addressing issues including electric vehicles, energy security and climate policy. Keep up with top takeaways from those discussions and other climate news from Davos in our bulletin, which we’ll update throughout the day.

In energy transition’s “messy phase”, climate policy falters but clean tech marches on

Politicians may be struggling to free themselves from the clutches of fossil fuel interests, but that won’t slam the brakes on the march of clean tech and renewables worldwide, former US Vice-President and longtime climate advocate Al Gore said at Davos on Wednesday.

Moderating one of the first panels on day two in an almost empty room, he made a stab at answering the question posed by the World Economic Forum: “How do we avoid a climate recession?”

Gore said he sees “a climate policy recession, but not a recession in the energy transition”. That, he explained, is because policy is controlled by governments – “and too many governments are now, unfortunately, controlled by special interests”, namely the fossil fuel industry which is “significantly better at capturing politicians than at capturing emissions”.

The result has been “schizophrenic” policy on addressing climate change in some countries, including in the US, he said, with periods of slamming on the brakes and “going back to the dirty fossil fuels” to satisfy the industry.

In the real world, however, the advantages of renewable energy have become obvious, as have the consequences of the climate crisis, he added, listing a litany of recent impacts.

On the technology front, Gore pointed out that in 2025, of all new electricity generation installed worldwide, 93% was renewables, and “the only thing coming down faster in price than solar panels is utility-scale batteries, because the production is doubling every year”. “So we don’t have a recession in the movement toward this energy transition, in my opinion,” he added.

Entrepreneur Zhang Lei, founder and CEO of Envision, which develops technology for clean energy systems and AI-powered energy digital platforms, said there may be some swings in climate policy but “the fundamental physics is actually improving”.

He pointed to an 80% drop in the price of energy storage in the last three years, which he said opens up a lot of opportunities to increase the penetration of wind and solar. That, he added, is exactly what is needed to meet the upsurge in electricity demand driven by the advent of artificial intelligence (AI), describing renewables as “infinite and inexpensive energy resources”.

Fossil fuels, by contrast, are “finite” and therefore not up to the job of powering an AI-based future, with electricity supply expected to increase by 10 times in the next 15 years. Renewables, however, are competitive and approaching “zero marginal cost”, he noted.

“We are so lucky to have renewable energy ready” to take advantage of “great prosperity” driven by AI, Zhang Lei added, noting China’s pivotal role in providing the necessary clean tech to much of the world.

Investment by China is making the renewable energy transition “irreversible”, argued Elizabeth Thurbon, professor of international political economy and director of the Green Energy Statecraft Project at the University of New South Wales.

China will stay on this path, she added, because the government understands that the energy transition “is a massive national security multiplier” by boosting economic security, energy security, environmental security, social security through jobs and geo-strategic security.

Globally, however, she warned that the transition is “in a really messy, messy phase”, due largely to poor governance, especially across a lot of Western countries.

Carsten Schneider, Germany’s environment minister, argued that the European Union, for one, has not taken its foot off the climate policy pedal, agreeing a new emissions reduction goal of 90% by 2040 last December. But that was a hard-fought win, amid pressure from some coal-reliant Eastern European countries to soften the target.

EU’s new climate target lines up multibillion-dollar boost for carbon markets

On Tuesday afternoon, in a separate panel, Andrew Forrest, executive chairman and founder of Australian mining company Fortescue, advised politicians and business people not to waver in their commitment to the energy transition – from an economic perspective, if nothing else.

He spoke of his company’s plan to save up to a billion dollars per year in operating costs by removing over a billion litres of diesel from its supply chains by 2030, replacing the dirty fuel used by trucks, trains and ships with renewable energy and batteries. This will improve Fortescue’s efficiency and competitiveness, and cut pollution, Forrest added, enabling it to outperform its peers.

He appealed to fellow business and political leaders to follow economic sense, urging them not to turn away from renewables in 2026 “because the winds of politics blew your values over”.

The post Climate at Davos: Clean tech powers on despite policy wobbles appeared first on Climate Home News.

Climate at Davos: Clean tech powers on despite policy wobbles

Climate Change

Adopting low-cost ‘healthy’ diets could cut food emissions by one-third

Choosing the “least expensive” healthy food options could cut dietary emissions by one-third, according to a new study.

In addition to the lower emissions, diets composed of low-cost, healthy foods would cost roughly one-third as much as a diet of the most-consumed foods in every country.

The study, published in Nature Food, compares prices and emissions associated with 440 local food products in 171 countries.

The researchers identify some food groups that are low in both cost and emissions, including legumes, nuts and seeds, as well as oils and fats.

Some of the most widely consumed foods – such as wheat, maize, white beans, apples, onions, carrots and small fish – also fall into this category, the study says.

One of the lead authors tells Carbon Brief that while food marketing has promoted the idea that eating environmentally friendly diets is “very fancy and expensive”, the study shows that such diets are achievable through cheap, everyday foods.

Meanwhile, a separate Nature Food study found that reforming the policies that reduce taxes on meat products in the EU could decrease food-related emissions by up to 5.7%.

Costs and emissions

The study defines a healthy diet using the “healthy diet basket” (HDB), which is a standard based on nutritional guidelines that includes a range of food groups with the needed nutrients to provide long-term health.

Using both data on locally available products and food-specific emissions databases, the authors estimate the costs and greenhouse gas emissions of 440 food products needed for healthy diets in 171 countries.

They examine three different healthy diets: one using the most-consumed food products, one using the least expensive food products and one using the lowest-emitting food products.

Each of these diets is constructed for each country, based on costs, emissions, availability and consumption patterns.

The researchers find that a healthy diet comprising the most-consumed foods within each country – such as beef, chicken, pork, milk, rice and tomatoes – emits an average of 2.44 kilograms of CO2-equivalent (kgCO2e) and costs $9.96 (£7.24) in 2021 prices, per person and per day.

However, they find that a healthy diet with the least-expensive locally available foods in each country – such as bananas, carrots, small fish, eggs, lentils, chicken and cassava – emits 1.65kgCO2e and costs $3.68 (£2.68). That is approximately one-third of the emissions and one-third of the cost of the most-consumed products diet.

In comparison, a healthy diet with the lowest-emissions products – such as oats, tuna, sardines and apples – would emit just 0.67kgCO2e, but would cost nearly double the least-expensive diet, at $6.95 (£5.05).

This reveals the tradeoffs of affordability and sustainability – and shows that the least-expensive foods tend to produce lower emissions, according to the study.

Dr Elena Martínez, a food-systems researcher at Tufts University and one of the lead authors of the study, tells Carbon Brief this is generally true because lower-cost food production tends to use fewer fossil fuels and require less land-use change, which also cuts emissions.

Ignacio Drake is coordinator of the fiscal and economic policies at Colansa, an organisation promoting healthy eating and sustainable food systems in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Drake, who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that the research is a “step further” than previous work on healthy diets. He adds that the study “integrates and consolidates” previous analyses done by other groups, such as the World Bank and the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

Food group differences

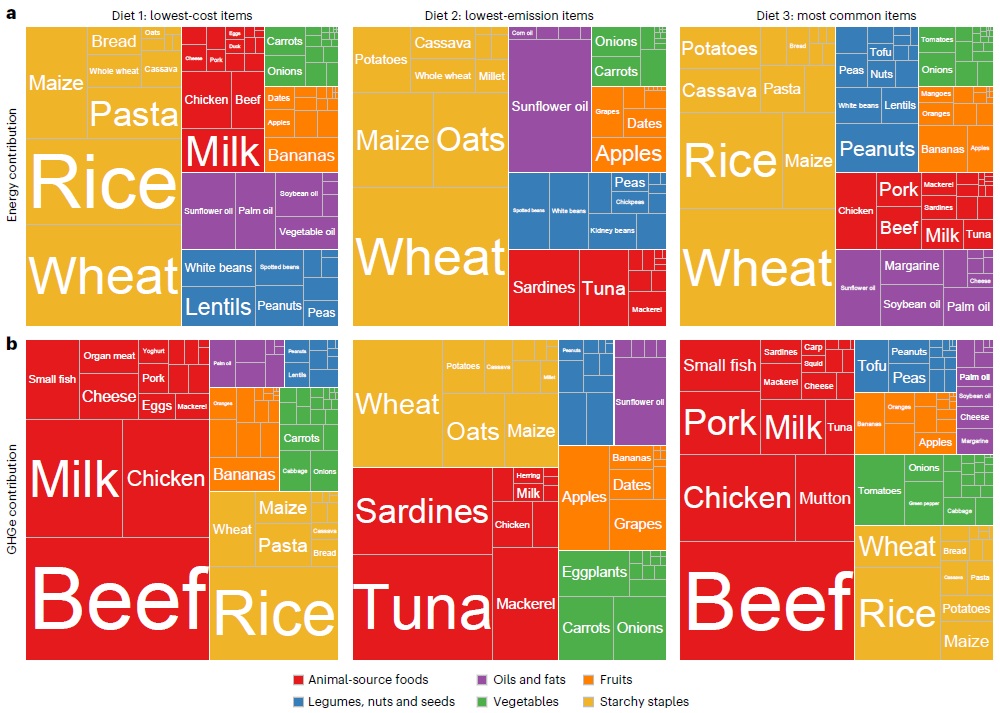

The research looks at six food groups: animal-sourced foods, oils and fats, fruits, legumes (as well as nuts and seeds), vegetables and starchy staples.

Animal-sourced foods – such as meat and dairy – are typically the most-emitting, and most-expensive, food group.

Within this group, the study finds that beef has the highest costs and emissions, while small fish, such as sardines, have the lowest emissions. Milk and poultry are amongst the least-expensive products for a healthy diet.

Starchy staple products also contribute to high emissions too, adds the study, because they make up such a large portion of most people’s calories.

Emissions from fruits, vegetables, legumes and oil are lower than those from animal-derived foods.

The following chart shows the energy contributions (top) and related emissions (bottom) from six major food groups in the three diets modelled by the study: lowest-cost (left), lowest-emission (middle) and most-common (right) food items.

The six food groups examined in the study are shown in different colours: animal-sourced foods (red), legumes, nuts and seeds (blue), oils and fats (purple), vegetables (green), fruits (orange) and starchy staples (yellow). The size of each box represents the contribution of that food to the overall dietary energy (top) and greenhouse gas emissions (bottom) of each diet.

Prof William Masters, a professor at Tufts University and author on the study, tells Carbon Brief that balancing food groups is important for human health and the environment, but local context is also important. For example, he points out that in low-income countries, some people do not get enough animal-sourced foods.

For Drake, if there are foods with the same nutritional quality, but that are cheaper and produce fewer emissions, it is logical to think that the “cost-benefit ratio [of switching] is clear”.

Other studies and reports have also modelled healthy and sustainable diets and, although they do not exclude animal-sourced foods, they do limit their consumption.

A recent study estimated that a global food system transformation – including a diet known as the “planetary health diet”, based on cutting meat, dairy and sugar and increasing plant-based foods, along with other actions – can help limit global temperature rise to 1.85C by 2050.

The latest EAT-Lancet Commission report found that a global shift to healthier diets could cut non-CO2 emissions from agriculture, such as methane and nitrous oxide, by 15%. The report recommends increasing the production of fruit, vegetable and nuts by two-thirds, while reducing livestock meat production by one-third.

Dr Sonia Rodríguez, head of the department of food, culture and environment at Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health, says that unlike earlier studies, which project ideal scenarios, this new study also evaluates real scenarios and provides a “global view” of the costs and emissions of diets in various countries.

Increasing access

The study points out that as people’s incomes increase, their consumption of expensive foods also increases. However, it adds, some people with high income that can afford healthy diets often consume other types of foods, due to reasons such as preferences, time and cooking costs.

The study stresses that nearly one-third of the world’s population – about 2.6 billion people – cannot afford sufficient food products required for a healthy diet.

In low-income countries, primarily in sub-Saharan Africa and south Asia, 75% of the population cannot afford a healthy diet, says the study.

In middle-income countries, such as China, Brazil, Mexico and Russia, more than half of the population can afford such a diet.

To improve the consumption of healthy, sustainable and affordable foods, the authors recommend changes in food policy, increasing the availability of food at the local level and substituting highly emitting products.

Martínez also suggests implementing labelling systems with information on the environmental footprint and nutritional quality of foods. She adds:

“We need strategies beyond just reducing the cost of diets to get people to eat climate-friendly foods.”

Drake notes that there are public and financial policies that can help reduce the consumption of unhealthy and unsustainable foods, such as taxes on unhealthy foods and sugary drinks. This, he adds, would lead to better health outcomes for countries and free up public resources for implementing other policies, such as subsidies for producing healthy food.

Separately, another recent Nature Food study looks at taxes specifically on meat products, which are subject to reduced value-added tax (VAT) in 22 EU member states.

It finds that taxing meat at the standard VAT rate could decrease dietary-related greenhouse gases by 3.5-5.7%. Such a levy would also have positive outcomes for water and land use, as well as biodiversity loss, according to the study.

The post Adopting low-cost ‘healthy’ diets could cut food emissions by one-third appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Adopting low-cost ‘healthy’ diets could cut food emissions by one-third

Climate Change

Big fishing nations secure last-minute seat to write rules on deep sea conservation

As a treaty to protect the High Seas entered into force this month with backing from more than 80 countries, major fishing nations China, Japan and Brazil secured a last-minute seat at the table to negotiate the procedural rules, funding and other key issues ahead of the treaty’s first COP.

The Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) pact – known as the High Seas Treaty – was agreed in 2023. It is seen as key to achieving a global goal to protect at least 30% of the planet’s ecosystems by 2030, as it lays the legal foundation for creating international marine protected areas (MPAs) in the deep ocean. The high seas encompass two-thirds of the world’s ocean.

Last September, the treaty reached the key threshold of 60 national ratifications needed for it to enter into force – a number that has kept growing and currently stands at 83. In total, 145 countries have signed the pact, which indicates their intention to ratify it. The treaty formally took effect on January 17.

“In a world of accelerating crises – climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution – the agreement fills a critical governance gap to secure a resilient and productive ocean for all,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres said in a statement.

Julio Cordano, Chile’s director of environment, climate change and oceans, said the treaty is “one of the most important victories of our time”. He added that the Nazca and Salas y Gómez ridge – off the coast of South America in the Pacific – could be one of the first intact biodiversity hotspots to gain protection.

Scientists have warned the ocean is losing its capacity to act as a carbon sink, as emissions and global temperatures rise. Currently, the ocean traps around 90% of the excess planetary heat building up from global warming. Marine protected areas could become a tool to restore “blue carbon sinks”, by boosting carbon absorption in the seafloor and protecting carbon-trapping organisms such as microalgae.

Last-minute ratifications

Countries that have ratified the BBNJ will now be bound by some of its rules, including a key provision requiring countries to carry out environmental impact assessments (EIA) for activities that could have an impact on the deep ocean’s biodiversity, such as fisheries.

Activities that affect the ocean floor, such as deep-sea mining, will still fall under the jurisdiction of the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

Nations are still negotiating the rules of the BBNJ’s other provisions, including creating new MPAs and sharing genetic resources from biodiversity in the deep ocean. They will meet in one last negotiating session in late March, ahead of the treaty’s first COP (conference of the parties) set to take place in late 2026 or early 2027.

China and Japan – which are major fishing nations that operate in deep waters – ratified the BBNJ in December 2025, just as the treaty was about to enter into force. Other top fishing nations on the high seas like South Korea and Spain had already ratified the BBNJ last year.

Power play: Can a defensive Europe stick with decarbonisation in Davos?

Tom Pickerell, ocean programme director at the World Resources Institute (WRI), said that while the last-minute ratifications from China, Japan and Brazil were not required for the treaty’s entry into force, they were about high-seas players ensuring they have a “seat at the table”.

“As major fishing nations and geopolitical powers, these countries recognise that upcoming BBNJ COP negotiations will shape rules affecting critical commercial sectors – from shipping and fisheries to biotechnology – and influence how governments engage with the treaty going forward,” Pickerell told Climate Home News.

Some major Western countries – including the US, Canada, Germany and the UK – have yet to ratify the treaty and unless they do, they will be left out of drafting its procedural rules. A group of 18 environmental groups urged the UK government to ratify it quickly, saying it would be a “failure of leadership” to miss the BBNJ’s first COP.

Finalising the rules

Countries will meet from March 23 to April 2 for the treaty’s last “preparatory commission” (PrepCom) session in New York, which is set to draft a proposal for the treaty’s procedural rules, among them on funding processes and where the secretariat will be hosted – with current offers coming from China in the city of Xiamen, Chile’s Valparaiso and Brussels in Belgium.

Janine Felson, a diplomat from Belize and co-chair of the “PrepCom”, told journalists in an online briefing “we’re now at a critical stage” because, with the treaty having entered into force, the preparatory commission is “pretty much a definitive moment for the agreement”.

Felson said countries will meet to “tidy up those rules that are necessary for the conference of the parties to convene” and for states to begin implementation. The first COP will adopt the rules of engagement.

She noted there are “some contentious issues” on whether the BBNJ should follow the structure of other international treaties such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), as well as differing opinions on how prescriptive its procedures should be.

“While there is this tension on how far can we be held to precedent, there is also recognition that this BBNJ agreement has quite a bit to contribute in enhancing global ocean governance,” she added.

The post Big fishing nations secure last-minute seat to write rules on deep sea conservation appeared first on Climate Home News.

Big fishing nations secure last-minute seat to write rules on deep sea conservation

-

Climate Change5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits